Abstract

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia (ARVC/D) is a genetic form of cardiomyopathy (CM) usually transmitted with an autosomal dominant pattern. It primary affects the right ventricle (RV), but may involve the left ventricle (LV) and culminate in biventricular heart failure (HF), life threatening ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (SCD). It accounts for 11%–22% of cases of SCD in the young athlete population. Pathologically is characterized by myocardial atrophy, fibrofatty replacement and chamber dilation.

Diagnosis is often difficult due to the nonspecific nature of the disease and the broad spectrum of phenotypic variations. Therefore consensus diagnostic criteria have been developed and combined electrocardiography, echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) and myocardial biopsy. Early detection, family screening and risk stratification are the cornerstones in the diagnostic evaluation. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) implantation, ablative procedures and heart transplantation are currently the main therapeutic options.

Keywords: Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC/D), cardiomyopathy, sudden cardiac death, tachyarrhythmias

Introduction

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia (ARVC/D) is a genetic form of cardiomyopathy that primarily affects the right ventricle (RV). It may also involve the left ventricle (LV) and culminate in life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias, prompting sudden cardiac death (SCD) and/or biventricular heart failure.1–5 ARVC/D was first described by the Pope’s physician, Giovanni Maria Lancisi, in his book entitled De Motu Cordis et Aneurysmatibus, published in 1736.6 He reported that there was a family who had experienced pathologic RV, heart failure and SCD in four generations. The first comprehensive clinical description of the disease was reported by Marcus et al in 1982, when he reported 24 adult cases with ventricular tachyarrhythmias with left bundle branch morphology.7 Nevertheless, it was not until 1984 that the electrocardiographic features of the disease were first described, including the epsilon wave.8

ARVC/D is characterized pathologically by myocardial atrophy, fibrofatty replacement, fibrosis and ultimate thinning of the wall with chamber dilation and aneurysm formation.9 These changes consequently produce electrical instability precipitating ventricular tachycardia (VT) and SCD.10–20

Epidemiology

The estimated prevalence of ARVC/D in the general population is approximately 1:5000, affecting men more frequently than women with a ratio of 3:1.21,22 ARVC/D accounts for 11%–22% of cases of SCD in the young athlete patient population,23–25 accounting for approximately 22% of cases in athletes in northern Italy26 and about 17% of SCD in young people in the United States.27

It has been difficult to determine the incidence of ARVC/D due to the different clinical manifestations of the disease. These manifestations vary greatly, especially in different ethnic groups. This is probably secondary to its genetic heterogeneity and variable phenotypic expression, along with a diverse disease progression, which make diagnosis difficult, and in turn, decreases the real incidence evaluation of this entity.

These ethnic variations are likely caused by different modes of inheritance and involved genes. For instance, in Naxos Island, Greece, the mode of inheritance of ARVC/D in association with palmoplantar keratosis, also known as Naxos disease, was demonstrated to be autosomal recessive,28 whereas the mode of inheritance in most of ARVC/D is autosomal dominant. Other studies suggest that Chinese patients may have a lower familial incidence of premature SCD among ARVC/D patients compared to Western population, although there is no genetic data on this population.29

Disease Genetics and Pathogenesis

ARVC/D was initially believed to be secondary to a developmental defect of the RV myocardium, leading to the original designation of “dysplasia”, similar to Uhl’s anomaly.30 Nonetheless, this process differs from ARVC/D based on the fact that Uhl’s anomaly has not been documented to have a genetic basis, and it is not recognized as a desmosomal disease. In addition, myocardial atrophy is the consequence of cell death after birth and its progressive postnatal development has been definitively assessed (See Table 1).26,31,32 This concept has evolved over the last 30 years and based on its clinical characteristics, pathophysiology, post-natal development and genetic background, its inclusion in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of cardiomyopathies was finally achieved.33,34

Table 1.

Differences between Uhl’s anomaly and ARVC/D.

| Mode of Inheritance | Pathogenic Mechanisms | Age at presentation | Presentation | Disease’s progression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uhl’s Anomaly | Rarely familial | Apoptotic dysplasia with complete absence of the myocardium32 | Usually is diagnosed in neonatal or infant life. Male:female ratio 1.27:131,32 |

Cyanosis, dyspnea, RV dilation and heart failure | Does not progress |

| ARVC/D | Most autosomic dominant, some variants are inherited in a recessive pattern | Apoptotic dysplasia of the myocardium followed by fibrofatty infiltration32 | Usually patients present symptoms during adolescence Male:female ration 2.28:132 | Range from asymptomatic, palpitations, atypical chest pain to ventricular arrhythmias and heart failure | Progressive postnatal development |

Several studies have been performed to determine the etiology and pathogenesis of ARVC/D. However, there still is conflicting evidence. Different causes have been suggested such as congenital defects, genetics and acquired factors. The hypothesis of a congenital cause leads to the adoption of the term dysplasia due to its association with Uhl’s anomaly, as explained earlier, but ARVC/D has been differentiated and its natural history through adult life has been well documented.3,30 This hypothesis has evolved into the idea of genetically determined cardiomyopathy, which has been retained on genetic grounds.33,34 In approximately 30%–50% of cases it is transmitted with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, with incomplete penetrance and variable expression.35–37

Acquired factors have also been suggested as the cause of ARVC/D. The strongest association has been made with viral myocarditis inducing arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. On histopathology, a lymphocytic infiltrate with disappearance of myocytes and fibrofatty replacement is often found, which can also be seen in viral myocarditis.38,39 It is possible that the wide variation in presentation of ARVC/D patients could be explained by its genetic heterogeneity and modifying factors such as exercise and/or viral myocarditis.23,40,41

The genetic hypothesis has been thoroughly studied. The first chromosomal locus identified was published by Rampazzo44 et al in 1994 in Italy. Linkage analysis supported the evidence for genetic heterogeneity of several ARVC/D loci on chromosomes 1, 2, 3, 6, 10, 12 and 14.42–45 Similarly, he reported the Desmoplakin gene (DSP), the first desmosomal protein gene to be associated with a major form of the disease, with autosomal dominant inheritance, also called ARVC/D type 846 (See Table 2).46–51

Table 2.

Different types of ARVD/C and its genetics.

| Type | Gene | Locus | Prevalence | Mode of inheritance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARVD1 | TGFB3 | 14q23-q24 | Rare | AD |

| ARVD2 | RYR2 | 1q42-q43 | Rare | AD |

| ARVD3 | ? | 14q12-q22 | Unknown | AD |

| ARVD4 | ? | 2q32.1-q32.3 | Unknown | AD |

| ARVD5 | TMEM43 | 3p23 | Unknown | AD |

| ARVD6 | ? | 10p14-p12 | Unknown | AD |

| ARVD7 | ? | 10q22.3 | Unknown | AD |

| ARVD8 | DSP | 6p24 | 6%–16%46 | AD/AR |

| ARVD9 | PKP2 | 12p11 | 11%–43%47,48 | AD |

| ARVD10 | DSG2 | 18q12.1-q12 | 7%–26%49–51 | AD |

| ARVD11 | DSC2 | 18q12.1 | Rare | AD |

| ARVD12 | JUP | 17q21 | Rare | AR |

In addition, the gene for Naxos disease was mapped on chromosome 17 (locus 17q21), by McKoy et al.28,43 This is the first disease-causing gene, also named junction plakogoblin (JUP) gene (autosomal recessive variant of ARVC/D) characterized by palmoplantar keratosis, woolly hair and ARVC/D. The association between skin and heart manifestations could be explained by the finding that epidermal cells in the soles, palms and myocyte share a similar mechanical junctional apparatus (fascia adherens and desmosome) responsible for cell-to-cell adhesion, and are exposed to the high frictional stress. The JUP gene encodes the desmosomal protein, plakoglobin, a major cytoplasmic protein that is the only known constituent common to submembranous plaques of both desmosomes and intermediate junctions responsible for cell adhesion. This suggests that ARVC/D is a cell-to-cell junction disease, leading detachment of the myocytes and fibrosis, particularly under conditions of mechanical stress.21,28,43,46,52

A recessive mutation of DSP has been reported and associated with Carvajal syndrome, another cardiocutaneous disease.53 Plakophilin-2 (PKP2) is the most frequent targeted protein with more than 25 different mutations identified in the gene encoding it.52 Thus, ARVC/D was found to be mainly a disease of the cardiomyocyte junction.54 (See Table 3).

Table 3.

Cardiocutaneous disorders associated with ARVC/D.

| Presentation | Genetics | Cardiac manifestations | Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naxos disease | Diffuse non-epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma with woolly hair and cardiomyopathy | Recessive mutation of desmoplakin and plakoglobin, in C 17 (JUP gene) and C 12, but there is new evidence for extensive locus heterogeneity. | ECG is abnormal in 90% of patients, RV structural and functional abnormalities are common. Presentation is usually syncope and/or sustained ventricular tachycardia during adolescence with a peak in young adulthood. | Predominant RV involvement Fatty infiltration is common. |

| Carvajal syndrome | Striate palmoplantar keratoderma with woolly hair and cardiomyopathy. | A recessive mutation of desmoplakin. Gene map locus 6p24 | Abnormal myocardial stretch, dilatation later fibrosis and progressive cardiac failure. Common features are: non compacted LV and recurrent VT/VF with sudden death. | Predominant LV involvement. Fatty infiltration is less common. |

Furthermore, extradesmosomal genes, unrelated to the cell adhesion complex, have been implicated as autosomal dominant forms of ARVC/D, such as (1) the cardiac ryanodine-2 receptor gene, responsible for the release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum; (2) the transforming growth factor-β3 gene (TGFβ3), implicated in the regulation of the production of extra-cellular matrix and expression of genes encoding desmosomal proteins and the TMEM43 genes.55–57

Clinical Presentation

ARVC/D is a devastating disease given the fact that the first symptom is often SCD, which makes early detection and a family screening test the cornerstone in the diagnostic evaluation. In a study of 100 patients with ARVC/D, Dalal et al reported an incidence of SCD of 23% in the United States. Other common presentations were palpitations (27%) and syncope (26%).23 Early intervention with an Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator (ICD) decreases the risk of SCD, but ARVC/D is a progressive disease, which can progress to refractory/recalcitrant VT or a ventricular fibrillation (VF) storm despite ICD therapy.

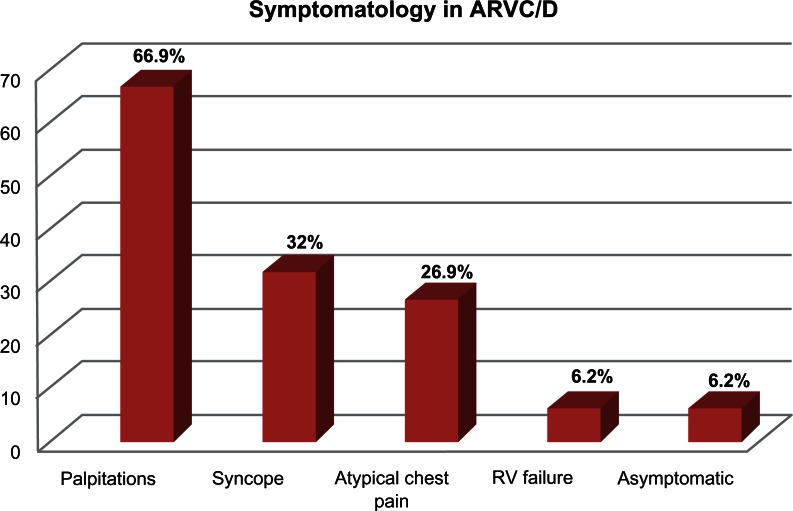

Other studies have suggested that up to up to 67% of individuals with ARVC/D present with palpitations, 32% present with syncope, 27% with atypical chest pain, 6% with RV failure and 6% may remain asymptomatic. (See Fig. 1).58 The most common arrhythmia is sustained or nonsustained monomorphic VT that originates in the RV and therefore has a left bundle branch block (LBBB) morphology. Alternatively, in some cases where the LV is involved, VT could present with a right bundle branch block (RBBB) morphology. These symptoms are usually exercise-related, mainly due to an activation of the sympathetic nervous system, which may lead to premature beats and re-entrant arrhythmogenic circuits. In a pathological myocardial substrate, this can perpetuate the incidence of life-threatening arrhythmias.

Figure 1.

Presenting symptoms and frequencies in patients with ARVC/D.58

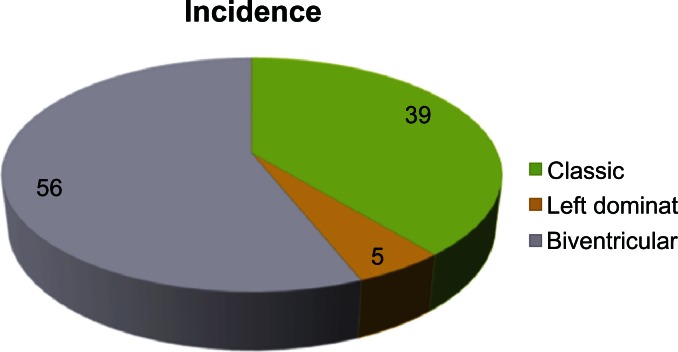

The advanced stage of ARVC/D is characterized by signs and symptoms of RV or LV failure depending on which ventricle is more affected (in the classic form, it is generally the RV more affected than the LV), and finally frank biventricular congestive heart failure, which may be difficult to distinguish clinically from dilated cardiomyopathy. (See Fig. 2).58

Figure 2.

Incidences of ventricular involvement in ARVC/D. Classic form are mostly RV involvement, LV or Biventricular involvement.58

Clinicopathologic Manifestations

The genotypic abnormalities explained above translate into phenotypic presentations with variable penetration, leading to the anatomoclinic profile of ARVC/D.

The histological examination of the myocardium reveals a typical fibrofatty infiltration with areas of surviving myocytes and inflammation progressing from epicardium to endocardium. This infiltration may be diffuse or regional; the latter is typically located at the angles of the “triangle of dysplasia” at the infero-apical and infundibular walls. This occurs earlier in the RV, compared to the left side of the heart, but LV involvement may also sporadically occur in early stages of the disease.8,33,59 Parietal thinning as well as endocardial thickening is found in areas of transmural infiltration and aneurismal dilation providing a substrate for life-threatening arrhythmias.

Biventricular involvement with LV fibrofatty replacement and involvement have been found as much as in 70% of the cases of ARVC/D. It is usually age dependent, associated with more severe cardiomegaly, arrhythmogenic events, inflammatory infiltrates and heart failure. ARVC/D can no longer be regarded as isolated disease of the RV.60 Accordingly, several authors have opted for naming this condition “Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy” but the term “Right Ventricular Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy” is still widely used.

The natural history of ARVC/D is highly variable, with a wide spectrum of clinical presentations. Four patterns have been proposed:24,33 (1) Concealed form, minor arrhythmias, which usually go unnoticeable. The diagnosis is usually made during family screening.61 (2) Overt Electrical Heart disorder, the most typical presentation, which usually occurs in young patients presenting with severe and symptomatic ventricular arrhythmias and SCD.62 (3) RV failure, in which the myocardial replacement in the RV leads to RV dysfunction with pump failure. (4) Biventricular failure characterized by progressing dilation of RV and LV; this usually develops late in the natural history of the disease.3,60 Other conditions have also been associated such as valvulopathies (ie, mitral valve prolapse63 and tricuspid valve prolapse) and patent foramen ovale.64,65 The mechanism of this association is still not known. We have postulated two different mechanisms: (1) raised left atrial pressure, as seen in patients with heart failure as they can dilate the foramen ovale leading to left-to-right shunt, while RV failure and tricuspid regurgitation can lead to rise in right atrial pressure and cause right-to-left shunt. (2) Apoptotic dysplasia, genetically determined by chromosome abnormalities, leading to loss of cell-to-cell adhesion and consequently patent foramen ovale and/or valvulopathies.

It is important to emphasize that fibrofatty infiltration is possibly the least reliable criterion for the diagnosis of ARVC/D,66 as fat may also be part of scarring from ischemia, inflammation and myocyte vacuolization, as seen in other cardiomyopathies. Therefore, its histopathological diagnosis should be done in conjunction with other features: fibrosis, tissue deposition, myocytes and inflammatory infiltration.

Diagnoses

ARVC/D should be suspected in a young patient with palpitations, syncope or aborted SCD. VT with LBBB morphology is the classic presentation, but as mentioned above, VT with RBBB may be present if the LV is involved. Other electrocardiographic abnormalities such as inverted T waves in right precordial leads (V1–V3) and frequent premature ventricular complex (PVCs), even in asymptomatic patients, should arouse the suspicion for this cardiomyopathy.67

Clinical diagnosis of ARVC/D is often difficult because of the non-specific nature of the disease and the broad spectrum of phenotypic variations. There is no definitive diagnostic standard. Endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) of the RV is definitive (gold standard) when positive but it often yields a false-negative result and in most patients, assessment of transmural myocardium is not possible based on the fact that the disease spreads from epicardium to endocardium. Therefore, it is not practical in the clinical setting.68,69 The sensitivity of EMB is approximately 67% because of the regional fibroadipose infiltration.70 Consequently, the best approach in making a diagnosis of ARVC/D is by combining different diagnostic tests.

Several investigations contribute to the diagnosis of ARVC/D. Consensus diagnostic criteria have been developed, which include RV biopsy, non-invasive electrocardiography, family history and imaging evaluation with echocardiography, cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) and angiography.71,72 The advent of the molecular genetics era has made a tremendous diagnostic impact and contributed new insights to the understanding of its pathophysiology.21

In the last decade, enormous advances have been made, which include two research grants in Europe and USA achieved by Basso et al and Marcus et al respectively.73,74 These have greatly contributed to the disease characterization, diagnosis, pathophysiology and therapeutic options.

The 1994 Task Force criteria were based upon clinical experience, family history, and structural, functional and electrocardiographic abnormalities in patients with severe disease.35 Thus, these criteria have high specificity but lack sensitivity, increasing the risk of a false negative in the early stages of ARVC/D. A modification of these original criteria was made in order to include first degree relatives on early stage of the disease or incomplete expression. This increased the sensitivity, but not surprisingly also increased the risk of false positives cases.75,76 These diagnostic criteria were revised in 2010 and now incorporate the advances in both technology and genetics (See Table 4).72

Table 4.

2010 revised task force criteria.

| Major | Minor |

|---|---|

| I. Global or regional dysfunction and structural alterations* | |

By 2D echo

|

By 2D echo

|

| II. Tissue characterization of wall | |

|

|

| III. Repolarization abnormalities | |

|

|

| IV. Depolarization/conduction abnormalities | |

|

|

| V. Arrhythmias | |

|

|

| VI. Family history | |

|

|

Notes: Definite = 2 major OR 1 major + 2 minor; Borderline = 1 major + 1 minor OR 3 minor; Possible = 1 major OR 2 minor.

Modified from: Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the task force criteria. Circulation. Apr 6, 2010;121(3):1533–41.

Abbreviations: PLAX, Parasternal Long-Axis; PSAX, Parasternal Short-Axis; RVOT, Right Ventricular Outflow Tract; BSA, body surface area.

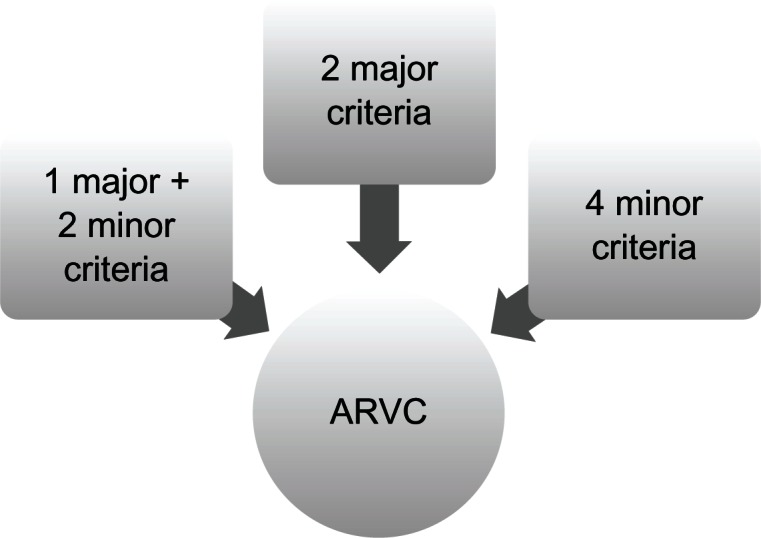

The diagnosis is based on the presence of major and minor criteria, which are classified into six categories. The diagnosis of ARVC/D is made in the presence of two major or one major plus two minor criteria or four minor criteria taken from different groups. (See Fig. 3).72

Figure 3.

Diagnosis of ARVC/D: major and minor criteria.72

Diagnostic Modalities

-

Electrocardiogram (ECG): almost 90% of patients with ARVC/D have some ECG abnormality. One of the most common presentations is prolonged S-wave upstroke > 55 ms in V1–V3 (90%–95%) followed by an inverted T wave on precordial leads (V1–V3), which occurs in one-half of cases presenting with VT. Inverted T waves (repolarization abnormality) are included in the 2010 Revised Task Force Criteria (see Table 4)72 and constitute a major criterion in the absence of complete RBBB.72,77,78 QRS prolongation (QRS > 110 msec), particularly in lead V1 has been observed in 24%–70% of patients with ARVC/D, which may be due to delayed activation of the RV rather than to any intrinsic abnormality in the right bundle branch.79,80

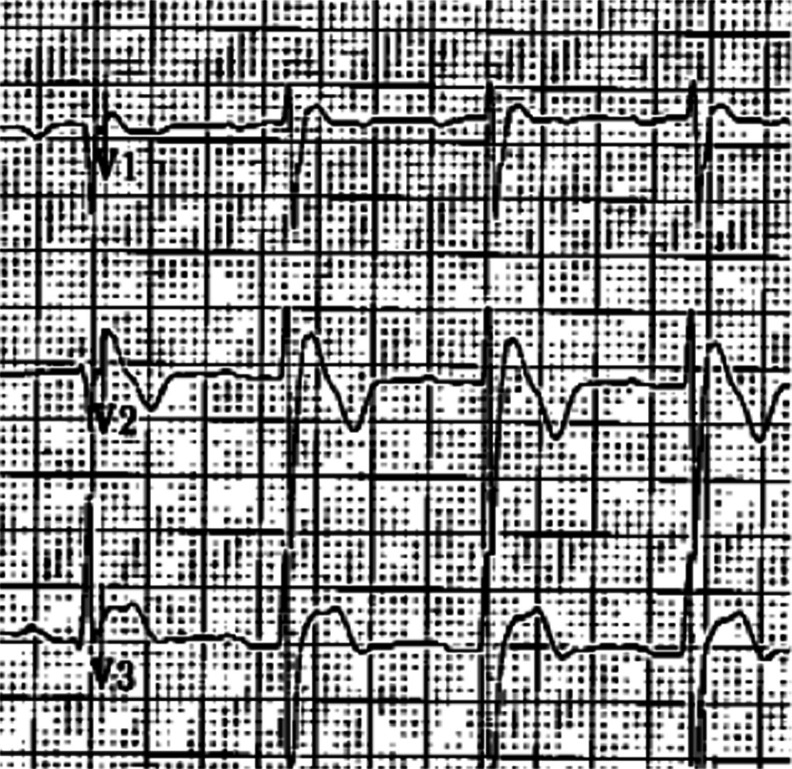

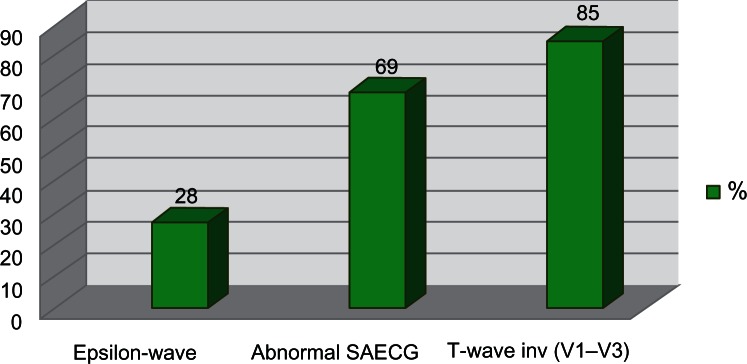

An epsilon wave (depolarization abnormality) may be found in 30%–33% of patients with ARVC/D58 and it is described as a distinct wave at the end of QRS complex (see Fig. 4) probably secondary to slowed intraventricular conduction. This is also a major criterion in the 2010 revised Task Force criteria (see Table 4, IV).72 Ventricular ectopy with LBBB morphology is also highly suggestive of ARVC/D. The origin of the ectopic beats is usually from one of the three regions of fatty degeneration in the “triangle of dysplasia”. (See Table 5).23,58,79,80

Signal average electrocardiogram (SAECG): Three criteria have been used: (1) the filtered QRS duration ≥ 114 ms. (2) low-amplitude signal ≥ 38 ms. (3) root mean square amplitude of the last 40 ms of the QRS ≤ 20 μV. The sensitivity improves to 69% from 47% when 1 of 3 criteria is used, instead of 2 of 3 criteria, while maintaining a high specificity of 95%. An abnormal SAECG (defined by 1 of 3 criteria) was associated with a dilated RV, an increased RV volume and a decreased RV ejection fraction on CMR.81 (See Fig. 558 and Table 4, IV).72

Echocardiography: Echocardiography reveals RV structural abnormalities such as RV dilation, aneurysm formation and functional abnormalities including hypokinetic RV, RV failure, paradoxical septal motion and tricuspid regurgitation. On late stages, LV involvement with biventricular failure is observed. In the 2010 revised Task Force criteria, echocardiographic criteria include quantitative measures of right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) enlargement and reduction in the RV fractional area changed. These major criteria yield 95% specificity (see Table 4, I).72

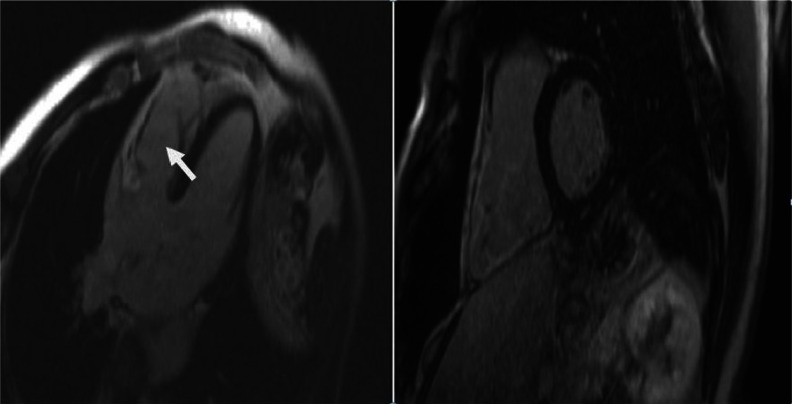

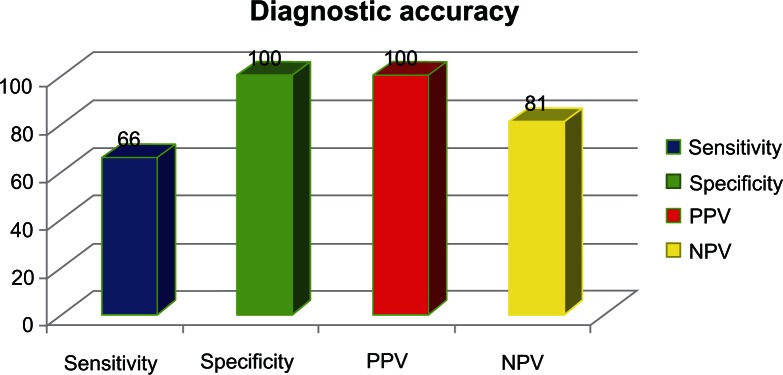

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR): CMR is widely used for the diagnosis of ARVC/D. CMR can identify global or regional ventricular dilation, dysfunction, intramyocardial fat, aneurysmatic dilation and fibrosis. Fatty infiltration of the RV is not diagnostic of ARVC/D. According to the proposed 2010 diagnostic criteria, an enlarged RV is no longer sufficient, because it may be seen in other infiltrative diseases such as sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, congenital heart diseases and pulmonary hypertension. The diagnostic criteria now require the presence of akinesia, dyskinesia or aneurysm in addition to a decreased RV ejection fraction or increased RV end diastolic volume to body surface area ratio (see Table 4, I).72 More recently, delayed enhancement CMR (DE MRI) has been proposed and tested in the diagnosis of ARVC/D, particularly for the detection of fibrotic tissue. In a recent study by Tandri et al,82 this technique showed a sensitivity of 66% with a specificity of 100% as well as a PPV of 100% and a NPV of 81%. These values make this modality very attractive and promising in making the diagnosis of ARVC/D. (See Fig. 6). Diagnosis accuracy of cardiac Delayed Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging (DE-MRI).82 (See Fig. 7).

Right ventricular angiography: The 2010 revised Task Force Criteria include as a major criterion the presence of regional RV akinesis, dyskinesis or aneurysm by RV angiogram. Its specificity is 90%; however, this is a very subjective and observer-dependent test. (See Table 4, I).72

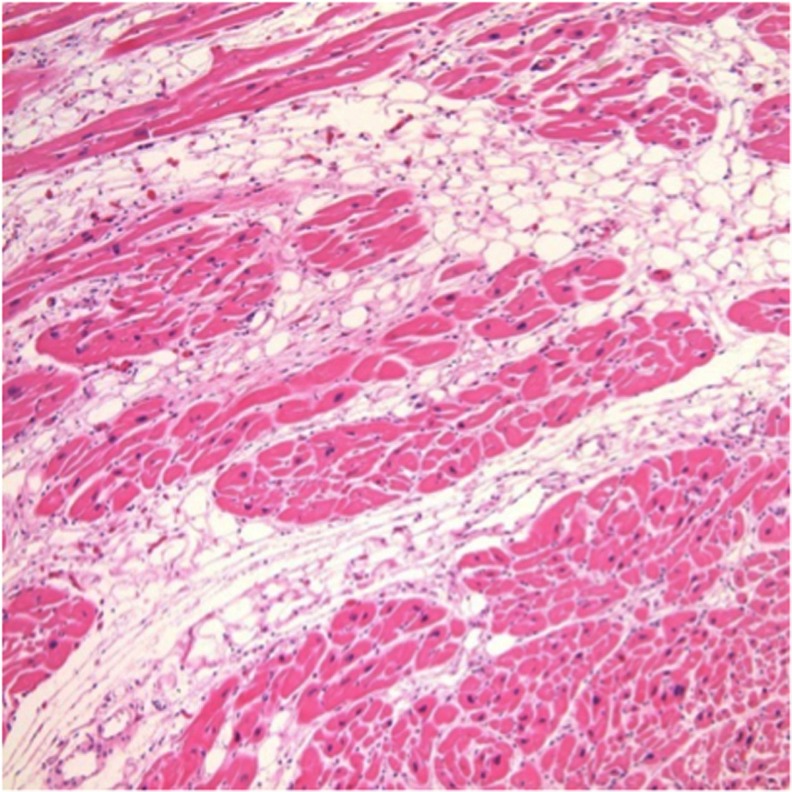

Right ventricular biopsy: Right ventricular biopsy is highly specific but lacks sensitivity, mainly because the fibrofatty infiltration is not uniform. The disease progression from epicardium to endocardium and most biopsy samples are taken from the ventricular septum, which is commonly not involved in the disease process. (See Fig. 8). Thus, confirmation of the diagnosis of ARVC/D by biopsy is not commonly performed. The major change is that the 2010 revised Task Force criteria creates a quantitative criteria instead of a qualitative one, which include the following as a major criterion: Residual myocytes < 60% by morphometric analysis (or <50% if estimated), with fibrous replacement of the RV free wall myocardium in ≥1 sample, with or without fatty replacement of tissue on endomyocardial biopsy. (See Table 4, II).72

Figure 4.

Epsilon wave: low amplitude positive deflection at the end of the QRS complex, usually seen in V1 and V2. If the epsilon wave is of large magnitude a reciprocal epsilon wave may be seen in V5 or V6, this may suggest that large part of the RV is depolarizing late.

Table 5.

ECG changes in ARVD/C.

| ECG changes | Frequency |

|---|---|

| 1. Prolonged S-wave upstroke > 55 ms in V1–V3 | 90%–95%23,58 |

| 2. T waves inversion in precordial leads | 82%–85%58 |

| 3. QRS widening in V1–3 | 25%–70%58,80 |

| 4. Epsilon wave | 30%58 |

| 5. Right bundle branch block (RBBB) | 18%–22%58,79 |

| 6. Paroxysmal episodes of ventricular tachycardia with a LBBB morphology | One of the most common findings |

Figure 5.

Incidence of ECG findings in ARVC/D.

Figure 6.

Diagnostic accuracy of noninvasive detection of myocardial fibrosis in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy using delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging.82.

Figure 7.

Delayed enhancement magnetic resonance imaging. 4-chamber and short axis views of DE-CMR showing delayed enhancement of the free right ventricular wall.

Notes: The arrow indicates the area of delayed enhancement, which represents fibrofatty replacement. The figure on the right shows a significantly dilated RV.

Figure 8.

The imaging is a Haematoxylin and eosin stained section and shows the typical fibrofatty infiltration of the ventricles in ARVC/D.

Note: The fibroadipose replacement advances from the epicardium to the endocardium and is associated with myocardial atrophy and myocytes loss.

Other tests

Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT): MDCT is used as an alternative to CMR for patients in whom CMR is contraindicated. Nevertheless, CMR is a better diagnostic modality than MDCT for patients with ARVC/D.

Radionuclide ventriculography: Radionuclide ventriculography can also detect regional and/or global RV dysfunction.

Despite all these different diagnostic modalities, no test is perfect. Diagnosis is difficult and requires the combination of all tests, if possible. Recent advances in technology promise to make DE MRI the imaging modality of choice to assess myocardial diseases.82 Nevertheless, this modality is not included in the current modified Task Force criteria (See Fig. 6).82

Differential Diagnosis

Right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia (RVOT) is one of the main differential diagnoses of ARVC/D. The presentation and electrocardiographic characteristics of VT could be very similar in these two (VT with LBBB but with an inferior axis). However, RVOT tachycardia is considered to be a primary electrical disease in the absence of structural heart disease, unlike ARVC/D. Epidemiologically, RVOT tachycardia is more common than ARVC/D.

Other conditions that should be differentiated from ARVC/D are: cardiac sarcoidosis,83 pre-excited AV re-entry tachycardia, Brugada syndrome (See Fig. 9), pulmonary hypertension, tricuspid valvulopathy and other congenital heart disease such as Uhl’s anomaly (See Table 1), and repaired Tetralogy of Fallot, among others. (See Table 6).

Figure 9.

Brugada syndrome: characterized by a dynamic ST-segment elevation (accentuated J wave) in leads V1 to V3 of the ECG followed by negative T wave.

Table 6.

Differential diagnosis of ARVC/D.

| Acquired heart diseases | Congenital heart disease | Miscellaneous |

|---|---|---|

| Tricuspid valvulopathy | Repaired tetralogy of fallot | Idiopathic RVOT tachycardia |

| RV infarction | Ebstein’s anomaly | Pre-excited AV re-entry tachycardia |

| Pulmonary hypertension | Atrial septal defect (ASD) | Dystrophica myotonica |

| Bundle branch re-entrant tachycardia | Uhl’s anomaly | Brugada syndrome |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | Partial anomalous venous return |

Treatment

As discussed previously, patients with ARVC/D may remain asymptomatic or may present with a wide variety of symptoms. Therefore, the therapeutic strategy has to be individualized, based on clinical presentation, risk stratification and patient/physician preference.22,60,83–86 The main goal of therapy is to prevent serious events, which requires identifying high-risk patients for malignant arrhythmias and SCD.87–89

Although several studies have evaluated the benefit of pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies in patients with ARVC/D,87–91 large prospective randomized trials are not available. Consequently, the current therapeutic recommendations for this entity have been developed from observational studies and case series, or have been adopted from other cardiomyopathies,92,93 where solid evidence supported by clinical trials is available and clear guidelines are defined.87,89

Physical activity

Exercise has been related to an increased incidence of ventricular conduction disorders, SCD, worsening symptoms and progression of the fibrofatty atrophy,22,78,94–96 particularly in young patients and competitive athletes.86,97 In 1996 Leclercq et al95 described the association between progressive sympathetic stimulation present during physical activity and the onset of monomorphic sustained VT. The initiation of the VT was associated with the typical catecholamine surge seen on exercise in the setting of the presence of arrhythmogenic substrate characteristic of these patients.22,95 For that reason, high risk patients with suspected or confirmed ARVC/D diagnosis should avoid vigorous physical activity including competitive sports, regular training and strenuous exertion involving abrupt physical effort, as well as any recreational activity associated with symptoms (Level of Recommendation: IB).96–98

Pharmacological therapy

Antiarrhythmic medications have been used for symptomatic control in patients who are not candidates for an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) or as an adjunct therapy to reduce frequent ICD discharges due to recurrent VT.89,99 Antiarrhythmic medications have been mostly recommended in patients with severe LV dysfunction and severe symptoms of ventricular arrhythmias. Beta-adrenergic blocking agents have shown effectiveness in reducing adrenergically-stimulated arrhythmias.22,85,100,101 Nevertheless, the evidence available has been derived from observational studies, which have shown conflicting results.

The combination of beta-blockers and amiodarone100 have had a beneficial effect in suppression of non-sustained VT, reduction in the frequency of sustained ventricular arrhythmias,91 and reduction of VT rate preventing syncope and favoring antitachycardia pacing termination rather than shock therapy. Furthermore, they favor the suppression of other arrhythmias, especially supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) and atrial fibrillation which may cause symptoms or interfere with ICD function, resulting in inappropriate discharges.91

Sotalol and amiodarone have been proposed as effective treatment of sustained VT or ventricular fibrillation (VF) as adjunctive therapy to ICD or in patients with ARVC/D that are not candidates for ICD implantation (Level of Recommendation: IIaC).89,91,99 In 1992, Wichter et al91 published that sotalol was the most effective medication in the treatment of both inducible and non-inducible VT with efficacy rates of 68.4 and 82.8% respectively, in patients with ARVC/D; patients who did not respond to sotalol were non-responders to other antiarrhythmic therapies including amiodarone. Class I antiarrhythmic drugs were effective in only a minority of patients (14.8% and 18.5%), and beta-blockers did not show effectiveness in patients with inducible VT and were only partially effective in patients with non-inducible VT (28%). Amiodarone was not superior to sotalol, being effective in 15.4 and 25% of the respective groups, and verapamil was more effective in non-inducible VT group (0% vs. 50%).

In contrast to the results published by Wichter, in 2009 Marcus et al102 reported that neither beta-blockers nor sotalol seemed to be protective against clinically relevant ventricular arrhythmias. Moreover, the sotalol group was found to have a potential increased risk for significant ventricular arrhythmias or ICD therapy. However, is important to recognize that high risk patients for major arrhythmias were most likely to be on sotalol. On the other hand, amiodarone, although only received by a relatively small number of patients, had the greatest efficacy in preventing ventricular arrhythmias. This study was done in 95 patients with ICD implantation selected from the North America ARVC Registry. These conflicting results need to be further addressed in future trials.

Non Pharmacologic Treatment

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD)

The indications of ICD for primary prevention of SCD in ARVC/D patients have not been well established.87,89 It represents prophylactic implantation based on a clinical profile with 1 or more identifiable risk factors for SCD. There is a consensus that high-risk patients should be considered as ICD placement candidates. Consequently, patients with episodes of sustained VT or VF (Level of Recommendation: IB), unexplained syncope, non-sustained VT on noninvasive monitoring, familial history of sudden death, extensive disease including those with LV involvement and good functional status (Level of Recommendation: IIaC)87,89,103 are potential candidates for ICD implantation even in the absence of ventricular arrhythmias.104,105 Additionally, patients with genotypes of ARVC/D associated with a high risk for SCD (eg, ARVC/D 5) should be considered as possible candidates for ICD therapy.87,104 It is currently recommended that asymptomatic patients have to be managed in a case by case basis.

In 2005, Hodgkinson et al104 identified 11 families from Newfoundland, Canada who were affected by autosomal-dominant ARVC/D5, which is related to mutation at chromosome 3-3p25 and is associated with early SCD, especially in men. 48 high risk patients were followed after ICD implantation (35 patients) (73%, 17 males and 18 females) for primary prevention and 13 patients (27%, males) for secondary prevention. Likewise, 58 matched high-risk patients without ICD were selected as a control group (32 males and 22 females). The authors reported a five-year mortality rate of 0% for males after ICD implantation compared to 28% in controls. In this study, homogeneous ARVC/D5 patients were studied in order to evaluate the real impact on mortality of ICD implantation. However, its clinical applicability may be reduced to patients with this specific genetic defect and may not be applied in practice to all patients with ARVC/D.

There are not specific prospective randomized trials for secondary prevention of SCD in an ARVC/D population, or comparing medical therapy versus ICD. Some observational studies have shown adequate ICD use for malignant ventricular arrhythmias/SCD in patients with ARVC/D.93,104,106–110 Nevertheless, there are well-defined recommendations for ICD placement in patients who survived to a cardiac arrest due to VF, or after facing a sustained VT with hemodynamic compromise with no evidence of reversible causes (Level of Recommendation: IA).87,88,93,110 For secondary prevention of SCD, ICD placement has improved survival compared with pharmacological options, regardless of the underlying myocardial disease.87,89,111–114

Corrado et al described an observational study focused in the impact of ICD therapy on SCD prevention in an ARVC/D population.93 They followed 132 patients after successful implantation due to cardiac arrest, sustained VT with and without hemodynamic compromise, unexplained syncope and family history of SCD due to ARVC/D. During a mean follow-up of 3.3 years, they observed that 48% of the subjects received appropriate ICD intervention (rate of 15% per year) for episodes of VTs with a similar incidence of appropriate termination in patients classified by clinical presentation. The total patient survival rate of 96% in patients with ICD compared with a 72% of the projected SCD-free survival rates without the device in 3.3 years (P < 0.001). Significant predictors of malignant ventricular arrhythmias, such as history of cardiac arrest or VT with hemodynamic compromise (10% incidence per year despite antiarrhythmic drug), unexplained syncope (8% per year), younger age and left ventricular involvement were identified.

Bhonsale et al115 recently published important predictors of appropriate ICD intervention in patients with ARVC/D who received ICD implantation for primary prevention of SCD, which include: proband status, the presence of NSVT, inducibility at EPS and a Holter PVC count > 1,000/24 hours, but only the presence of NSVT and inducibility after EPS remained significant predictors of appropriate ICD interventions on multivariable analysis. This is an important step in understanding and identifying predictor of appropriate therapy in these patients and developing risk stratification scheme in ARVC/D patients.115

Complications from ICD implantation

Although there is clear evidence of the benefit of ICD implantation as a secondary prevention mechanism for SCD, the devices are not free of short- and long-term complications. The variation of the myocardium structure with fibrofatty infiltration and RV endomyocardial scarring can produce difficulties in ICD lead placement, leading to inadequate sensing and procedural complications like myocardial injury or aneurysmal rupture.22 Patients with ARVC/D who required ICD placements are usually younger compared to patients with ICD due to other diseases.93 This situation leads to an increased lifetime risk of device-related complications, associated with implantation, leads, pulse generator and functionality,110,116,117 as well as deleterious psychosocial effects and detriment of quality of life.118,119 Finally, the current guidelines discourage the placement of defibrillators in patients with incessant VT, VF or with significant psychiatric illnesses that may be aggravated by device implantation or that may preclude systematic follow-up. (Level of Recommendation: IIIC).87

ICD programming

The prevention of inappropriate ICD shocks in these patients could be increased by programming certain variables which include: faster ventricular-tachycardia/ventricular-fibrillation (VT/VF) thresholds and longer detection durations, activating enhanced detection criteria up to 200 bpm and deactivating sustained rate durations, activating algorithms to detect oversensing or lead problems and applying remote monitoring. Recently the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial-Reduce Inappropriate Therapy (MADIT-RIT) was published which proves that a high-rate therapy (delivered at a heart rate of ≥200 bpm) and delayed ICD therapy, as compared with conventional device programming, were associated with reductions in a first occurrence of inappropriate therapy and reductions in all causes of mortality.120 These findings may change the current practices with two new programming approaches, which minimize the overall shock burden.121–123

Radiofrequency ablation

Radiofrequency ablation has been reserved for patients with recurrent ventricular arrhythmias despite treatment with antiarrhythmic drugs.124–126 Ablation is considered a complementary therapy to ICD (Level of Recommendation: IIaC), useful for management of symptoms but may not be sufficient to prevent SCD.87,89 There is a high rate of recurrence after endocardial ablation due to the characteristic generalized, patchy involvement of the myocardium and progressive nature of this disease.124,125 It is worth pointing out that with newer current approaches for catheter ablation, by combining endocardial and epicardial ablation we can decrease the rate of recurrent VT. Multiple recent studies suggest that simultaneous epicardial and endocardial approaches for VT mapping and ablation are feasible and might even result in elimination of recurrent VT. This could be explained by the preferential epicardial infiltration of the disease.127

Surgical treatment

Surgical isolation of the RV free wall prevents the propagation of malignant arrhythmias from the RV to the LV; by performing this surgical procedure there would be less substrate for the electrical disturbance. This therapeutic approach was once an option for patients with VT refractory to antiarrhythmic medications.128–130 However, patients were at risk of postoperative RV failure. Over the last decades, this procedure has been replaced by ICD placement, which has achieved widespread acceptance as a preventive treatment for SCD.

In patients with late complications of the disease, who develop heart failure symptoms or life threatening and untreatable VT, heart transplantation could be an option with good short and long term survival. Heart transplantation is essentially the final therapeutic option for these patients.131

Other Recommendations

Additionally, patients with signs of ventricular failure should be given optimal therapy for heart failure and anticoagulation should be considered in patients with atrial fibrillation, significant ventricular dilation or ventricular aneurysm.60

Screening for asymptomatic family members

Once the diagnosis of ARVC/D has been confirmed, a systematic evaluation of the family members favors an early diagnosis of possible affected subjects.

Nava et al evaluated 365 subjects from 37 Italian families affected by ARVC/D. They found that 41% (151 subjects) of the family members were affected by the disease, with clinical manifestations present during the adolescence and young adulthood.78 They also observed a broad clinical spectrum of manifestations with incomplete expression and progressive natural history of the disease, recommending a long-term follow up of relatives. Family members who remain asymptomatic in the early “concealed” phase could still be at risk of disease progression and/or adverse cardiovascular events.72

In 2010, Marcus et al proposed a modification of the 1994 Task Force Criteria in order to improve the diagnostic sensitivity for early and familiar involvement,72 incorporating evidence available from genetics and technologic advances, including improvement of echocardiographic techniques and CMR. As part of the evaluation, an ECG, 24 hour Holter monitoring, echocardiogram and, if possible, a signal averaged ECG should be obtained on all first-degree relatives of patients diagnosed with ARVC/D. Family involvement is considered if there is evidence of ECG changes including T wave inversions in V1–V3 (individuals older than 14 years in the absence of RBBB), late potentials on SAECG, episodes of VT with RV origin pattern or more than 200 premature ventricular contractions in 24 hours, as well as the RV structural or functional abnormalities previously described.72,86

Quarta et al evaluated the roll of mutation analysis on familial evaluation with ARVC/D.132 The study enrolled 210 first-degree relatives and 49 living probands from 100 affected families. Data obtained from clinical assessment and screening of 5 desmosomal genes associated with the disease showed clinical expression in 41.9% of relatives, at least 1 mutation in 56 families and multiple desmosomal variants in 8 families. Multiple mutations were more common in probands than in relatives, and they were associated with a significant increase in risk of disease expression (ie, 5-fold in affected family members). On the other hand, the prevalence of the disease in affected first-degree relatives was similar after comparing probands with positive and negative mutation screening (28.9% vs. 20%, respectively; P = 0.57), suggesting possible non-identified genetic abnormalities.132

Although genetic analysis in not considered a contributor to risk stratification, it could be useful in families with history of SCD. Identification of pathogenic mutations in affected patients with cascade screening of relatives may offer an alternative cardiovascular evaluation of family members. Therefore, genetic counseling may be provided, assessing hereditary risks to next generations.72,89,132

Conclusion

ARVC/D is a progressive disease with life-threatening complications, which constitute a clinical diagnostic challenge for physicians, given the different genotypic and phenotypic variations and the wide ranges of clinical manifestations. The main challenge is to improve the risk stratification for better identification of high risk patients of SCD and heart failure, who most benefit from early intervention with lifestyle changes, restriction of physical activity, antiarrhythmic drugs, ICD placement, new ablation approaches with simultaneous endocardial and epicardial ablation and, if necessary, heart transplantation. These interventions are available and life saving, with the potential to change the natural history of the disease by offering a good quality and better life expectancy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Sherri White of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Jacobi Medical Center, Bronx, New York for providing histopathological images.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the review article: JR. Analyzed the data: EM, CM. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: EM, CM. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: RL. Agree with manuscript results and conclusions: JR. Jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper: EM. Made critical revisions and approved final version: JR, EM, CM. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript

Funding

Author(s) disclose no funding sources.

Competing Interests

Author(s) disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Disclosures and Ethics

As a requirement of publication author(s) have provided to the publisher signed confirmation of compliance with legal and ethical obligations including but not limited to the following: authorship and contributorship, conflicts of interest, privacy and confidentiality and (where applicable) protection of human and animal research subjects. The authors have read and confirmed their agreement with the ICMJE authorship and conflict of interest criteria. The authors have also confirmed that this article is unique and not under consideration or published in any other publication, and that they have permission from rights holders to reproduce any copyrighted material. Any disclosures are made in this section. The external blind peer reviewers report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Sabel KG, Olsson SB. A long term follow up of 15 patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Br Heart J. 1987;58(5):477–88. doi: 10.1136/hrt.58.5.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manyari DE, Klein GJ, Gulamhusein S, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia: a generalized cardiomyopathy? Circulation. 1983;68(2):251–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.68.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinamonti B, Sinagra G, Salvi A, et al. Left ventricular involvement in right ventricular dysplasia. Am Heart J. 1992;123(3):711–24. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90511-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Webb JG, Kerr CR, Huckell VF, Mizgala HF, Ricci DR. Left ventricular abnormalities in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Am J Cardiol. 1986;58(6):568–70. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fontaine G, Frank R, Fontaliran F, Lascault G, Tonet J. Right ventricular tachycardias. In: Parmley WW, Chatterjee K, editors. Cardiology. New York, NY: JB Lippincott Co; 1992. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lancisi G. De Motu Cordis et Aneurysmatibus Opus Posthumum In Duas Partes Divisum. Rome: Giovanni Maria Salvioni; 1728. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcus FI, Fontaine GH, Guiraudon G, et al. Right ventricular dysplasia: a report of 24 adult cases. Circulation. 1982;65(2):384–98. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.65.2.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fontaine G, Frank R, Guiraudon G, et al. Significance of intraventricular conduction disorders observed in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1984;77(8):872–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thiene G, Basso C, Danieli G, Rampazzo A, Corrado D, Nava A. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy a still underrecognized clinic entity. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1997;7(3):84–90. doi: 10.1016/S1050-1738(97)00011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dungan WT, Garson A, Jr, Gillette PC. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia: a cause of ventricular tachycardia in children with apparently normal hearts. Am Heart J. 1981;102(4):745–50. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(81)90101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foale RA, Nihoyannopoulos P, Ribeiro P, et al. Right ventricular abnormalities in ventricular tachycardia of right ventricular origin: relation to electro-physiological abnormalities. Br Heart J. 1986;56(1):45–54. doi: 10.1136/hrt.56.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fontaine G, Frank R, Tonet JL, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia: a clinical model for the study of chronic ventricular tachycardia. Jpn Circ J. 1984;48(6):515–38. doi: 10.1253/jcj.48.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halphen C, Beaufils P, Azancot I, Baudouy P, Manne B, Slama R. Recurrent ventricular tachycardia due to right ventricular dysplasia. Association with left ventricular anomalies. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1981;74(9):1113–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lemery R, Brugada P, Janssen J, Cheriex E, Dugernier T, Wellens HJ. Nonischemic sustained ventricular tachycardia: clinical outcome in 12 patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;14(1):96–105. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martini B, Nava A, Thiene G, et al. Monomorphic repetitive rhythms originating from the outflow tract in patients with minor forms of right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 1990;27(2):211–21. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(90)90162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martini B, Nava A, Thiene G, et al. Accelerated idioventricular rhythm of infundibular origin in patients with a concealed form of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Br Heart J. 1988;59(5):564–71. doi: 10.1136/hrt.59.5.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehta D, Odawara H, Ward DE, McKenna WJ, Davies MJ, Camm AJ. Echocardiographic and histologic evaluation of the right ventricle in ventricular tachycardias of left bundle branch block morphology without overt cardiac abnormality. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63(13):939–44. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nava A, Canciani B, Daliento L, et al. Juvenile sudden death and effort ventricular tachycardias in a family with right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 1988;21(2):111–26. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(88)90212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossi P, Massumi A, Gillette P, Hall RJ. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia: clinical features, diagnostic techniques, and current management. Am Heart J. 1982;103(3):415–20. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(82)90282-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rowland E, McKenna WJ, Sugrue D, Barclay R, Foale RA, Krikler DM. Ventricular tachycardia of left bundle branch block configuration in patients with isolated right ventricular dilatation. Clinical and electrophysiological features. Br Heart J. 1984;51(1):15–24. doi: 10.1136/hrt.51.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corrado D, Thiene G. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: clinical impact of molecular genetic studies. Circulation. 2006;113(13):1634–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.616490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gemayel C, Pelliccia A, Thompson PD. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(7):1773–81. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01654-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dalal D, Nasir K, Bomma C, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia: a United States experience. Circulation. 2005;112(25):3823–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.542266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corrado D, Fontaine G, Marcus FI, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy: need for an international registry. Study Group on Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy of the Working Groups on Myocardial and Pericardial Disease and Arrhythmias of the European Society of Cardiology and of the Scientific Council on Cardiomyopathies of the World Heart Federation. Circulation. 2000;101(11):E101–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.11.e101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corrado D, Basso C, Schiavon M, Thiene G. Screening for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in young athletes. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(6):364–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808063390602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thiene G, Nava A, Corrado D, Rossi L, Pennelli N. Right ventricular cardiomyopathy and sudden death in young people. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(3):129–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198801213180301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen WK, Edwards WD, Hammill SC, Gersh BJ. Right ventricular dysplasia: a need for precise pathological definition for interpretation of sudden death. Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:34A. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKoy G, Protonotarios N, Crosby A, et al. Identification of a deletion in plakoglobin in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy with palmoplantar keratoderma and woolly hair (Naxos disease) Lancet. 2000;355(9221):2119–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02379-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng TO. Ethnic differences in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2002;83(3):293. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00068-2. author reply 291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uhl H. A previously undescribed congenital malformation of the heart: almost total absence of the myocardium of the right ventricle. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1952;91:197–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wager GP, Couser RJ, Edwards OP, Gmach C, Bessinger B., Jr Antenatal ultrasound findings in a case of Uhl’s anomaly. Am J Perinatol. 1988;5(2):164–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-999678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerlis LM, Schmidt-Ott SC, Ho SY, Anderson RH. Dysplastic conditions of the right ventricular myocardium: Uhl’s anomaly vs. arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Br Heart J. 1993;69(2):142–50. doi: 10.1136/hrt.69.2.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Basso C, Thiene G, Corrado D, Angelini A, Nava A, Valente M. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Dysplasia, dystrophy, or myocarditis? Circulation. 1996;94(5):983–91. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.5.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson P, McKenna W, Bristow M, et al. Report of the 1995 World Health Organization/International Society and Federation of Cardiology Task Force on the Definition and Classification of cardiomyopathies. Circulation. 1996;93(5):841–2. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.5.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKenna WJ, Thiene G, Nava A, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Task Force of the Working Group Myocardial and Pericardial Disease of the European Society of Cardiology and of the Scientific Council on Cardiomyopathies of the International Society and Federation of Cardiology. Br Heart J. 1994;71(3):215–8. doi: 10.1136/hrt.71.3.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miani D, Pinamonti B, Bussani R, Silvestri F, Sinagra G, Camerini F. Right ventricular dysplasia: a clinical and pathological study of two families with left ventricular involvement. Br Heart J. 1993;69(2):151–7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.69.2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nava A, Thiene G, Canciani B, et al. Familial occurrence of right ventricular dysplasia: a study involving nine families. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;12(5):1222–8. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)92603-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calabrese F, Basso C, Carturan E, Valente M, Thiene G. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: is there a role for viruses? Cardiovasc Pathol. 2006;15(1):11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bowles NE, Ni J, Marcus F, Towbin JA. The detection of cardiotropic viruses in the myocardium of patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(5):892–5. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01688-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thiene G, Corrado D, Nava A, et al. Right ventricular cardiomyopathy: is there evidence of an inflammatory aetiology? Eur Heart J. 1991;12(Suppl D):22–5. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/12.suppl_d.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fontaliran F, Fontaine G, Brestescher C, Labrousse J, Vilde F. Significance of lymphoplasmocytic infiltration in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Apropos of 3 own cases and review of the literature. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1995;88(7):1021–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warnes CD, J . Congenital Heart disease in adults. In: Fuster V, Alexander W, O’Rourke RA, editors. Hurst’s, The Heart. 10th ed. New York: Mcgraw-Hill; 2000. pp. 1800–1801. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coonar AS, Protonotarios N, Tsatsopoulou A, et al. Gene for arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy with diffuse nonepidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma and woolly hair (Naxos disease) maps to 17q21. Circulation. 1998;97(20):2049–58. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.20.2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rampazzo A, Nava A, Erne P, et al. A new locus for arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVD2) maps to chromosome 1q42-q43. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4(11):2151–4. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.11.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Severini GM, Krajinovic M, Pinamonti B, et al. A new locus for arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia on the long arm of chromosome 14. Genomics. 1996;31(2):193–200. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rampazzo A, Nava A, Malacrida S, et al. Mutation in human desmoplakin domain binding to plakoglobin causes a dominant form of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71(5):1200–6. doi: 10.1086/344208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dalal D, Molin LH, Piccini J, et al. Clinical features of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy associated with mutations in plakophilin-2. Circulation. 2006;113(13):1641–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.568642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Tintelen JP, Entius MM, Bhuiyan ZA, et al. Plakophilin-2 mutations are the major determinant of familial arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2006;113(13):1650–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.609719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Awad MM, Dalal D, Cho E, et al. DSG2 mutations contribute to arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79(1):136–42. doi: 10.1086/504393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pilichou K, Nava A, Basso C, et al. Mutations in desmoglein-2 gene are associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2006;113(9):1171–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.583674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sen-Chowdhry S, Syrris P, Ward D, Asimaki A, Sevdalis E, McKenna WJ. Clinical and genetic characterization of families with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy provides novel insights into patterns of disease expression. Circulation. 2007;115(13):1710–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.660241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gerull B, Heuser A, Wichter T, et al. Mutations in the desmosomal protein plakophilin-2 are common in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet. 2004;36(11):1162–4. doi: 10.1038/ng1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Norgett EE, Hatsell SJ, Carvajal-Huerta L, et al. Recessive mutation in desmoplakin disrupts desmoplakin-intermediate filament interactions and causes dilated cardiomyopathy, woolly hair and keratoderma. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(18):2761–6. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.18.2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Basso C, Corrado D, Marcus FI, Nava A, Thiene G. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2009;373(9671):1289–300. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beffagna G, Occhi G, Nava A, et al. Regulatory mutations in transforming growth factor-beta3 gene cause arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 1. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65(2):366–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Merner ND, Hodgkinson KA, Haywood AF, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 5 is a fully penetrant, lethal arrhythmic disorder caused by a missense mutation in the TMEM43 gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(4):809–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tiso N, Stephan DA, Nava A, et al. Identification of mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene in families affected with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 2 (ARVD2) Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(3):189–94. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.3.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nasir K, Bomma C, Tandri H, et al. Electrocardiographic features of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy according to disease severity: a need to broaden diagnostic criteria. Circulation. 2004;110(12):1527–34. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000142293.60725.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thiene G, Basso C. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: An update. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2001;10(3):109–17. doi: 10.1016/s1054-8807(01)00067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Corrado D, Basso C, Thiene G, et al. Spectrum of clinicopathologic manifestations of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: a multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30(6):1512–20. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nava A, Thiene G, Canciani B, et al. Clinical profile of concealed form of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy presenting with apparently idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias. Int J Cardiol. 1992;35(2):195–206. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(92)90177-5. discussion 207–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Daliento L, Turrini P, Nava A, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in young versus adult patients: similarities and differences. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25(3):655–64. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00433-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martini B, Basso C, Thiene G. Sudden death in mitral valve prolapse with Holter monitoring-documented ventricular fibrillation: evidence of coexisting arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 1995;49(3):274–8. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(95)02294-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cubero JM, Gallego P, Pavon M. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and atrial right-to-left shunt. Acta Cardiol. 2002;57(6):443–5. doi: 10.2143/AC.57.6.2005471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hagenah G, Andreas S, Konstantinides S. Accidental left ventricular placement of a defibrillator probe due to a patent foramen ovale in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Acta Cardiol. 2004;59(4):449–51. doi: 10.2143/AC.59.4.2005214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Basso C, Thiene G. Adipositas cordis, fatty infiltration of the right ventricle, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Just a matter of fat? Cardiovasc Pathol. 2005;14(1):37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Niroomand F, Carbucicchio C, Tondo C, et al. Electrophysiological characteristics and outcome in patients with idiopathic right ventricular arrhythmia compared with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Heart. 2002;87(1):41–7. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fontaliran F, Fontaine G, Fillette F, Aouate P, Chomette G, Grosgogeat Y. Nosologic frontiers of arrhythmogenic dysplasia. Quantitative variations of normal adipose tissue of the right heart ventricle. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1991;84(1):33–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lobo FV, Heggtveit HA, Butany J, Silver MD, Edwards JE. Right ventricular dysplasia: morphological findings in 13 cases. Can J Cardiol. 1992;8(3):261–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Angelini A, Basso C, Nava A, Thiene G. Endomyocardial biopsy in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J. 1996;132(1 Pt 1):203–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(96)90416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Manyari DE, Duff HJ, Kostuk WJ, et al. Usefulness of noninvasive studies for diagnosis of right ventricular dysplasia. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57(13):1147–53. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90690-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the Task Force Criteria. Circulation. 2010;121(13):1533–41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.840827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Basso C, Wichter T, Danieli GA, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: clinical registry and database, evaluation of therapies, pathology registry, DNA banking. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(6):531–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Marcus F, Towbin JA, Zareba W, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C): a multidisciplinary study: design and protocol. Circulation. 2003;107(23):2975–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000071380.43086.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hamid MS, Norman M, Quraishi A, et al. Prospective evaluation of relatives for familial arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia reveals a need to broaden diagnostic criteria. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(8):1445–50. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Syrris P, Ward D, Asimaki A, et al. Clinical expression of plakophilin-2 mutations in familial arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2006;113(3):356–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.561654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jaoude SA, Leclercq JF, Coumel P. Progressive ECG changes in arrhythmogenic right ventricular disease. Evidence for an evolving disease. Eur Heart J. 1996;17(11):1717–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nava A, Bauce B, Basso C, et al. Clinical profile and long-term follow-up of 37 families with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(7):2226–33. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00997-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cox MG, Nelen MR, Wilde AA, et al. Activation delay and VT parameters in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy: toward improvement of diagnostic ECG criteria. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19(8):775–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fontaine G, Umemura J, Di Donna P, Tsezana R, Cannat JJ, Frank R. Duration of QRS complexes in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. A new non-invasive diagnostic marker. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris) 1993;42(8):399–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kamath GS, Zareba W, Delaney J, et al. Value of the signal-averaged electrocardiogram in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8(2):256–62. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tandri H, Saranathan M, Rodriguez ER, et al. Noninvasive detection of myocardial fibrosis in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy using delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(1):98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schionning JD, Frederiksen P, Kristensen IB. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia as a cause of sudden death. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1997;18(4):345–8. doi: 10.1097/00000433-199712000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hulot JS, Jouven X, Empana JP, Frank R, Fontaine G. Natural history and risk stratification of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2004;110(14):1879–84. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143375.93288.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sen-Chowdhry S, Lowe MD, Sporton SC, McKenna WJ. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. Am J Med. 2004;117(9):685–95. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Smith W. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Heart Lung Circ. 2011;20(12):757–60. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, et al. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 Guidelines for Device-Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices): developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2008;117(21):e350–408. doi: 10.1161/CIRCUALTIONAHA.108.189742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wichter T, Breithardt G. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: a role for genotyping in decision-making? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(3):409–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zipes DP, Camm AJ, Borggrefe M, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(5):e247–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Marcus FI, Fontaine GH, Frank R, Gallagher JJ, Reiter MJ. Long-term follow-up in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular disease. Eur Heart J. 1989;10(Suppl D):68–73. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/10.suppl_d.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wichter T, Borggrefe M, Haverkamp W, Chen X, Breithardt G. Efficacy of antiarrhythmic drugs in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular disease. Results in patients with inducible and noninducible ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 1992;86(1):29–37. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hauer RN, Aliot E, Block M, et al. Indications for implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) therapy. Study Group on Guidelines on ICDs of the Working Group on Arrhythmias and the Working Group on Cardiac Pacing of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2001;22(13):1074–81. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Corrado D, Leoni L, Link MS, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy for prevention of sudden death in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia. Circulation. 2003;108(25):3084–91. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000103130.33451.D2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fornes P, Ratel S, Lecomte D. Pathology of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia—an autopsy study of 20 forensic cases. J Forensic Sci. 1998;43(4):777–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Leclercq JF, Potenza S, Maison-Blanche P, Chastang C, Coumel P. Determinants of spontaneous occurrence of sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia in right ventricular dysplasia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28(3):720–4. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Maron BJ, Ackerman MJ, Nishimura RA, Pyeritz RE, Towbin JA, Udelson JE. Task Force 4: HCM and other cardiomyopathies, mitral valve prolapse, myocarditis, and Marfan syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(8):1340–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Furlanello F, Bertoldi A, Dallago M, et al. Cardiac arrest and sudden death in competitive athletes with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1998;21(1 Pt 2):331–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1998.tb01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Burke AP, Robinson S, Radentz S, Smialek J, Virmani R. Sudden death in right ventricular dysplasia with minimal gross abnormalities. J Forensic Sci. 1999;44(2):438–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Steinberg JS, Martins J, Sadanandan S, et al. Antiarrhythmic drug use in the implantable defibrillator arm of the Antiarrhythmics Versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID) Study. Am Heart J. 2001;142(3):520–9. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.117129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Leclercq JF, Coumel P. Characteristics, prognosis and treatment of the ventricular arrhythmias of right ventricular dysplasia. Eur Heart J. 1989;10(Suppl D):61–7. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/10.suppl_d.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Reiter MJ, Reiffel JA. Importance of beta blockade in the therapy of serious ventricular arrhythmias. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82(4A):9I–19I. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00468-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Marcus GM, Glidden DV, Polonsky B, et al. Efficacy of antiarrhythmic drugs in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: a report from the North American ARVC Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(7):609–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Corrado D, Calkins H, Link MS, et al. Prophylactic implantable defibrillator in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia and no prior ventricular fibrillation or sustained ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2010;122(12):1144–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.913871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hodgkinson KA, Parfrey PS, Bassett AS, et al. The impact of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy on survival in autosomal-dominant arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVD5) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(3):400–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zwanziger J, Hall WJ, Dick AW, et al. The cost effectiveness of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: results from the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial (MADIT)-II. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(11):2310–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Link MS, Wang PJ, Haugh CJ, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia: clinical results with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Jinterv Card Electrophysiol. 1997;1:41. doi: 10.1023/a:1009714718034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pezawas T, Stix G, Kastner J, Schneider B, Wolzt M, Schmidinger H. Ventricular tachycardia in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy: clinical presentation, risk stratification and results of long-term follow-up. Int J Cardiol. 2006;107(3):360–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Roguin A, Bomma CS, Nasir K, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(10):1843–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tavernier R, Gevaert S, De Sutter J, et al. Long term results of cardioverter-defibrillator implantation in patients with right ventricular dysplasia and malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Heart. 2001;85(1):53–6. doi: 10.1136/heart.85.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wichter T, Paul M, Wollmann C, et al. Implantable cardioverter/defibrillator therapy in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: single-center experience of long-term follow-up and complications in 60 patients. Circulation. 2004;109(12):1503–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121738.88273.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.A comparison of antiarrhythmic-drug therapy with implantable defibrillators in patients resuscitated from near-fatal ventricular arrhythmias. The Antiarrhythmics versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID) Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(22):1576–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711273372202. [No authors listed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Connolly SJ, Gent M, Roberts RS, et al. Canadian implantable defibrillator study (CIDS): a randomized trial of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator against amiodarone. Circulation. 2000;101(11):1297–302. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.11.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kuck KH, Cappato R, Siebels J, Ruppel R. Randomized comparison of antiarrhythmic drug therapy with implantable defibrillators in patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest: the Cardiac Arrest Study Hamburg (CASH) Circulation. 2000;102(7):748–54. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.7.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Siebels J, Kuck KH. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator compared with antiarrhythmic drug treatment in cardiac arrest survivors (the Cardiac Arrest Study Hamburg) Am Heart J. 1994;127(4 Pt 2):1139–44. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]