Abstract

Aurora A Kinase (AURKA) is overexpressed in 96% of human cancers and is considered an independent marker of poor prognosis. While the majority of tumors have elevated levels of AURKA protein, few have AURKA gene amplification, implying that posttranscriptional mechanism regulating AURKA protein levels are significant. Here we show that NEDD9, a known activator of AURKA, is directly involved in AURKA stability. Analysis of a comprehensive breast cancer tissue microarray revealed a tight correlation between the expression of both proteins, significantly corresponding with increased prognostic value. A decrease in AURKA, concomitant with increased ubiquitination and proteasome-dependent degradation, occurs due to depletion or knockout of NEDD9. Re-expression of wild type NEDD9 was sufficient to rescue the observed phenomenon. Binding of NEDD9 to AURKA is critical for AURKA stabilization, as mutation of S296E was sufficient to disrupt binding and led to reduced AURKA protein levels. NEDD9 confers AURKA stability by limiting the binding of the cdh1-substrate recognition subunit of APC/C ubiquitin ligase to AURKA. Depletion of NEDD9 in tumor cells increases sensitivity to AURKA inhibitors. Combination therapy with NEDD9 shRNAs and AURKA inhibitors impairs tumor growth and distant metastasis in mice harboring xenografts of breast tumors. Collectively, our findings provide rationale for the use of AURKA inhibitors in treatment of metastatic tumors and predict the sensitivity of the patients to AURKA inhibitors based on NEDD9 expression.

Keywords: breast cancer, NEDD9, AURKA, degradation, AURKA inhibitors

Introduction

The serine/threonine kinase, AURKA, is a proto-oncoprotein that is overexpressed in most cancers (1–3). High AURKA expression is strongly associated with decreased survival and is an independent prognostic marker (4). AURKA overexpression disrupts the spindle checkpoint activated by paclitaxel or nocodazole, inducing resistance to these compounds (5). Inhibition or depletion of AURKA protein may therefore improve the survival of patients resistant to paclitaxel (5). While 94% of the primary invasive mammary carcinomas have elevated AURKA protein levels (6), only 13.6% show AURKA gene amplification (1, 3). Thus, posttranscriptional mechanisms of AURKA stabilization are important in breast cancer.

AURKA is polyubiquitinated by the anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) complex and targeted for degradation by the proteasome (7). APC/C-dependent degradation of AURKA requires cdh1, which acts as a substrate recognition subunit for a number of mitotic proteins, including Plk1 and cyclin B. Overexpression of cdh1 reduces AURKA levels (8), whereas cdh1 knockdown or mutation of the AURKA cdh1 binding site, results in elevated AURKA expression (7–9). AURKA is ubiquitinated through the recognition of a carboxyl-terminal D-box (destruction box) and an amino-terminal A-box, specific for the destruction of AURKA (10–11). Phosphorylation of AURKA on Ser51 in the A-box, inhibits cdh1-APC/C-mediated ubiquitination and consequent AURKA degradation (9).

Cancer cells express high levels of AURKA independently of a cell cycle, which suggests that there are additional mechanisms of AURKA stabilization. Recently, a number of proteins were documented to be involved in the regulation of AURKA stability either by direct deubiquitination of AURKA (12), or through interference with AURKA ubiquitination by APC/C (PUM2, TPX2, LIMK2) (13–15.)

NEDD9 is a member of metastatic gene signature identified in breast adenocarcinomas and melanomas (16–18). NEDD9 is a cytoplasmic docking protein of the CAS family. NEDD9 regulates proliferation directly by binding to and activating AURKA (19). In non-transformed cells activation of AURKA by NEDD9 in interphase is tightly controlled by a limited amount of NEDD9 in cytoplasm. Overexpression of NEDD9 leads to activation of AURKA resulting in centrosomal amplification and aberrant mitosis (19). NEDD9 undergoes ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation by APC/C. Like typical APC/C substrates, NEDD9 has D-box motifs and cdh1 binds to a D-box located within the carboxyl-terminal domain (20–21).

The strong link between increased AURKA expression and cancer progression has stimulated development of AURKA inhibitors for cancer therapy. PHA-680632 (22–23), MLN8054 and MLN8237 (25) are potent small-molecule inhibitors of AURKA activity. These compounds have significant antitumor activity in various animal tumor models with favorable pharmacokinetics (23). However, clinical trials with MLN8054 as a single agent failed to show tumor growth inhibition (25, 29). In the present study, using human breast cell lines and xenografts, we have identified NEDD9 as a critical regulator of AURKA protein stability and sensitivity to AURKA inhibitors. Depletion of NEDD9 via shRNA decreases AURKA protein, sensitizes tumor cells to AURKA inhibitors, and eliminates metastasis in xenograft models of breast cancer. Combination therapy using NEDD9 shRNAs and AURKA inhibitors might prove to be an effective treatment strategy for solid tumors with NEDD9 overexpression.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and Reagents

shRNAs, siRNAs against human NEDD9, AURKA and control expressed in pGIPZ or in doxycycline-inducible pTRIPZ vectors (ThermoFisher Scientific). Lentiviral particles were prepared as previously described (26). Wild type, Ser296Ala-A, S296/298-AA or Ser296Glu-E and S296/298-EE cDNAs of murine NEDD9 were subcloned into pLUTZ lentiviral vector under doxycycline-inducible promoter. pcDNA3.1-myc-Ubiquitin and pcDNA3.1-HA-NEDD9 used for ubiquitination studies. Induction of shRNA or cDNA was done by addition of 1µg/ml doxycyline.

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

The cell lines MDA-MB-231, BT-549, BT-20, ZR-75-1, MCF7 and MDA-MB-231-luc-D3H2LN (MDA-MB-231LN), expressing luciferase (Caliper Life Sciences) were purchased and authenticated by American Type Culture Collection. After infection (or transfection) of shRNAs (or siRNAs) cells were selected for puromycin resistance and tested by WB.

Protein Stability Studies

Approximately 2 ×107 cells were plated, 12 hours later fresh medium containing cycloheximide (50 µg/mL) or MG132 (10 µM) was added for 12h. At indicated time intervals, cells were lysed in PTY buffer (19) with ubiquitin aldehyde (1–2µM), protease inhibitors (Sigma).

Cell Cycle Analysis by Flow Cytometry

The FACS analysis was done according to a previously published protocol (19). Cell cycle distribution was analyzed by FACSCalibur™ equipped with Cell Quest software.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

qPCR (27) was performed in an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR Cycler and analyzed using Applied Biosystems SDS software.

Immunohistochemical Analysis (IHC)

High density breast cancer tissue microarrays BR2082 (Supplementary Table1) were collected with full donor consent. IHC procedures done according to the manufacturer's recommendations (US Biomax Inc.) in duplicates. Manual scoring of staining intensity (negative (0), weak (1+), moderate (2+), or strong (3+)), as well as location, and cell types was completed by an independent pathologist from US Biomax, Inc. Each core was scanned by the Aperio Scanning System, at 20X. The total number of positive cells and the intensity of anti-NEDD9 staining were computed by Aperio ImageScope10.1 software based on the digital images taken from each core.

Western Blot Procedure and Antibodies

Western blotting procedures were previously described (26). Primary antibodies included: anti-NEDD9 mAb (2G9) (19), anti-NEDD9 (p55, custom made using NEDD9 1–394aa as an antigen), anti-β-actin mAb, or anti-GAPDH (Sigma), anti-AURKA (BD Biosciences), anti-AURKA (AurA-N, custom made using 1–126aa N-terminal fragment of AURKA), anti-phospho-T288Aurora A (Cell Signaling), anti-Histone H3 and anti-phospho-Ser10 Histone H3 and anti-Ubiquitin (Millipore, BD Biosciences). Blots were developed by the HyGLO HRP Detection Reagent (Denville Scientific, Inc.). Bands were digitized and quantified using a digital electrophoresis documentation and image analysis system (G-box, Syngene Corp.).

Protein Expression, GST Pull-down, and Immunoprecipitation (IP)

In vitro pull-down and IP protocols were previously published (19, 26). IP samples were incubated with anti-AURKA (AurA-N) or anti-NEDD9 (p55), immobilized on the A/G-protein Sepharose, or 4B-Glutathione agarose for GST pull-down (G&E Healthcare Life Sciences) at 4°C, washed and resolved by SDS–PAGE. His-tagged cdh1 protein (Novus International, Inc.), 50ng of recombinant AURKA and GST-HEF1 in AURKA buffer were used in the cdh1 titration pull-down.

Animal Studies

NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) immunodeficient mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (stock 5557). Animals were housed in the WVU Animal Facility under pathogen-free conditions; protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Primary tumor and organs with metastases were collected, processed, and analyzed by the WVU Department of Pathology Tissue Bank Core Facility.

Animal Bioluminescence Imaging (BLI)

Mice were injected with luciferase-expressing MDA-MB-231LN cells and imaged weekly for quantitative evaluation of tumor growth and dissemination. 150 mg/kg D-Luciferin (Caliper Life Sciences) was injected into the peritoneum. Images were obtained using the IVIS® Lumina-II Imaging System and Living Image-4.0 software.

Mammary fat pad injections: For animal studies, cells were grown, trypsinized, resuspended in DPBS (1×107 cells/ml), and 0.1 ml was injected into the 4th inguinal mammary gland of female mice 6–8 weeks of age and followed by BLI up to 6 weeks.

Tail vein injections: males were intravenously injected with 1×105 cells and followed by BLI once a week for 2–3 weeks total. Total radiance of lungs was calculated at each time point in control and treated animals. Lungs were imaged, fixed in formalin at the end point of study and analyzed for number and size of metastases by a pathologist.

Tumor Volume Measurement

Tumor size was assessed by Vevo2100 Micro-Ultrasound System. A 40 or 50 mHz transducer was used, depending on the tumor size, and a 3D image was acquired with 0.051 mm between images. Using the integrated software, the images were reconstructed to create a 3D image of the tumor.

AURKA Inhibitors Application

a) Cell lines studies. Cells were treated with MLN8054 (0–100nM) or PHA-680632 (0–400nM) inhibitors (Selleckchem) for 2–12h, disrupted in PTY buffer (19), processed for WB or immunofluorescence staining. b.) Xenograft studies. Compound administration began a) when primary tumors reached 150–200 mm3 in female mice or b) 24h post intravenous injection of tumor cells in male mice. MLN8237 is an improved analog of MLN8054 compound with increased stability suitable for in vivo studies. MLN8237 was dissolved in 10% 2-hydroxypropyl-b-cyclodextrin, 1% sodium bicarbonate in water. 20 mg/kg/dose were administered via oral gavage twice daily for 4 days/week for 2 weeks. MLN8237 was tested against a placebo control consisting of drug vehicle.

Statistical Analysis

Unpaired t-test, non-linear regression, or one/or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons were used for statistical analysis of the results. Experimental values were reported as standard error of mean (S.E.M). Differences in mean values were considered significant at p <0.05. Rates of tumor growth were established by linear regression of the bioluminescence data with time and cohort membership as covariates. Statistical calculations were performed using the GraphPad InStat software package.

Results

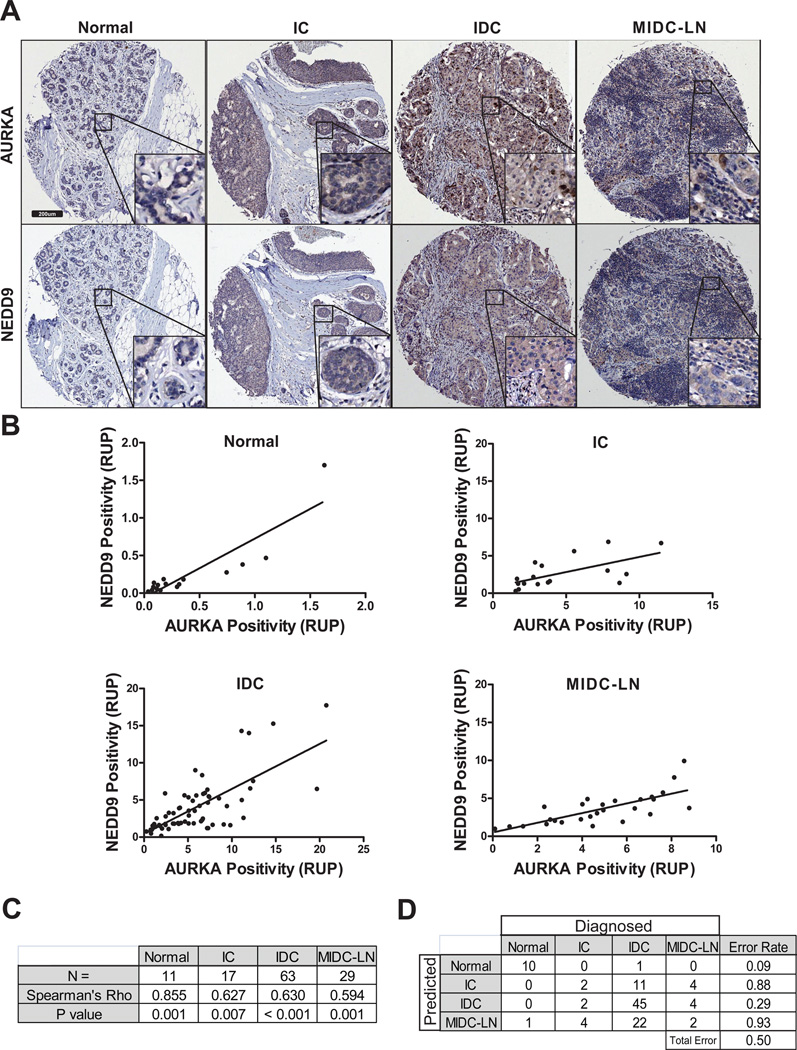

Increased NEDD9 expression tightly correlates with expression of AURKA protein in breast cancer

AURKA and NEDD9 are independently overexpressed in many human cancers (1–3, 16–18). We have previously shown that NEDD9 binds to and activates AURKA in cancer cells (19) and expression of AURKA alone was found to be an independent prognostic marker of poor survival. To determine if expression of both proteins could facilitate the diagnosis of certain types or stages of breast cancer, we performed immunohistochemical staining for NEDD9 and AURKA in 120 cases of breast cancer. Cases screened from a tissue microarray consisted of four groups of progressive disease stages: 1) normal tissue, 2) intraductal carcinoma (IC), 3) invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), and 4) metastatic IDC (MIDC) (Supplementary Table 1). Representative images of IHC staining for each group are shown in Fig.1A. Statistical analysis of staining intensity suggests that NEDD9 and AURKA expression positively correlate. The lowest expression and intensity of either protein was found in normal tissue, whereas a 10–20 fold increase in expression was observed in tumor samples (Fig.1B). Significant correlation between NEDD9 and AURKA expression was noted for all four evaluated tissue types (Fig.1C). The Spearman’s correlation coefficients for the normal, IC, IDC and MIDC groups are 0.85, 0.67, 0.63, 0.59 respectively, indicating a positive correlation (Fig.1C). A random forest fit of NEDD9 and AURKA positivity staining, which achieved an out-of-bag error rate of 0.508, indicates that by using NEDD9 and AURKA positivity scores, one can double the predictive power over chance (Fig.1D). To define the molecular mechanisms underlying NEDD9 and AURKA correlative expression profiles, we used a panel of human breast cancer cell lines where the levels of NEDD9 can be manipulated and controlled.

Figure 1. Increased NEDD9 expression correlates with expression of AURKA protein in invasive ductal breast adenocarcinomas.

(A). Representative images of immunohistochemical staining of tissue microarray with anti-AURKA (top panel) and anti-NEDD9 (bottom panel) antibodies; Normal breast tissue, intraductal carcinoma (IC), invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma, lymph nodes (MIDC-LN). Scale bar is 200µm. Insets represent x200 enlarged areas indicated in the main panel. (B). Quantification of NEDD9 and AURKA in RUP-relative units of positivity (percentage of cells stained positively in the same core stained by anti-AURKA or -NEDD9 antibodies). Most fitted lines were plotted on the graphs. (C). positivity data for both proteins were analyzed using Spearman’s Rho correlation. (D). positivity data for both proteins were analyzed by Random Forest statistical software.

Depletion of NEDD9 leads to dramatic decrease of AURKA protein in cells lines and animal models

The expression profiles of AURKA and NEDD9 in a panel of human breast cancer cell lines followed a pattern similar to that observed in the tissue microarray analysis. Invasive MDA-MB-231 (or highly invasive lymph node derived MDA-MB-231LN), MDA-MB-453, and ZR-75-1 cell lines had the highest levels of expression of NEDD9 and AURKA, followed by BT-549, and noninvasive MCF7 and BT-20 lines (Fig.2A). We next evaluated AURKA protein levels in mouse embryonic fibroblasts derived from NEDD9 knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) animals. AURKA expression levels were reduced in KO cells compared to WT cells (Fig.2B). Similar results were obtained by IHC analysis of tissue sections (Fig.2C), suggesting that maximal expression of AURKA is dependent on NEDD9.

Figure 2. Depletion of NEDD9 leads to dramatic decrease of AURKA protein.

(A). Western Blot (WB) analysis of NEDD9 and AURKA in breast cancer cell lines and (B) in mouse embryonic fibroblasts derived from wild type (WT) and NEDD9 knock out (KO) animals. (C). Representative IHC of anti-AURKA staining in kidney tissues, WT and NEDD9-KO mice. Staining with non-specific IgG (Con.). Scale bar is 25µm. (D). WB analysis and quantification of AURKA, NEDD9, GAPDH upon treatment with anti-NEDD9 (shN1, shN2) or non-specific (shCon) shRNAs, n=3, percentage of AURKA expression to shCon, standard error of mean (+/−S.E.M). Student’s one-tailed t-test **p=0.0006, **p=0.0024 (shCon/shN1 or /shN2), and no significant difference (ns) (shN1/shN2) in MCF7. **p=0.003 and **p=0.0094 (shCon/shN1 or /shN2), and ns (shN1/shN2) in MDA-MB-231. (E). WB analysis and quantification of AURKA and NEDD9 expression in shNEDD9 and shCon cells transfected with WT-NEDD9 or control-RFP (red fluorescent protein) cDNA; n=3, percentage of AURKA expression to shCon, normalized by GAPDH. Student’s one-tailed t-test *p=0.0186, **p=0.0012 (shCon/shN1 or /shN2), ns (shN1/shN2 or shN1/NEDD9 and shN2/NEDD9 re-expression).

Depletion of NEDD9 by two different shRNAs or siRNAs reduced the levels of AURKA protein by 60–80% (Fig.2D, Supplementary Fig.1A). In order to determine if the reduced levels of AURKA were due to transcriptional mechanisms or non-specific siRNA depletion, we performed qRT-PCR analysis for NEDD9 and AURKA. The NEDD9-targeting siRNAs did not affect the levels of AURKA mRNA (Supplementary Fig.1B), indicating that NEDD9 regulates AURKA at the protein level. Moreover, we were able to restore AURKA protein levels in shNEDD9 cells via re-expression of doxycycline-inducible WT-NEDD9 cDNA (Fig.2E).

Protein levels of NEDD9 and AURKA are tightly regulated during the cell cycle (28); therefore, we examined the effects of NEDD9 depletion on the cell cycle. FACS analysis of cells treated with siRNA targeting NEDD9 did not show significant difference in cell cycle distribution when compared to siCon (Supplementary Fig.1C). These results indicate that the decrease in AURKA protein level is NEDD9-dependent and post transcriptionally regulated.

NEDD9 regulates the stability of AURKA

To further evaluate how NEDD9 governs AURKA expression, we examined AURKA levels in shCon- and shNEDD9-MDA-MB-231LN cells treated with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX). CHX treatment led to an abrupt decrease in the amount of AURKA in shNEDD9 cells during the first 3 hours (Fig.3A). shCon cells had elevated AURKA levels for 6 hours and followed NEDD9 protein decay dynamics (Fig.3A). The half life of AURKA was 6 and 3 hours in shCon and shNEDD9, respectively (Fig.3B). The delayed decrease in AURKA protein levels in control cells compared with shNEDD9 indicates that AURKA protein stability is dependent on NEDD9.

Figure 3. NEDD9 regulates stability of AURKA through inhibition of proteasome-dependent degradation.

(A). WB analysis of AURKA and NEDD9 expression in shCon-, shNEDD9-MDA-MB-231LN cells treated with cyclohexamide. Expression was normalized by α-tubulin. (B). Quantification of AURKA as in (A), n=3, fold of change of AURKA expression to time point 0h, +/−S.E.M, one-way ANOVA ***p<0.0001, **p=0.005 (shCon/shN1 or /shN2) at each time point (except 0h). (C). WB analysis of AURKA, NEDD9 in shCon, shNEDD9 cells treated with MG132 or vehicle. (D). Quantification of AURKA expression as in (C, +MG132), n=3, fold of change to shCon, +/− S.E.M. Student’s t-test **p=0.0086, **p=0.0084 (shCon/shN1 or /shN2). (E). WB analysis of AURKA ubiquitination in WCL and IP from shCon or shNEDD9 cells transfected with pcDNA3-Myc-Ubiquitin, with MG132. (F). Quantification of AURKA ubiquitination as in (E, IP), n=3, fold of change to shCon, +/− S.E.M. Student’s t-test, **p=0.0098, *p=0.05 (shCon/shN1 or /shN2). (G). WB with anti-AURKA, anti-NEDD9 and anti-cdh1 antibodies. (H). Quantification of AURKA using the following formula (AURKA-IP/AURKA-total) normalized to NEDD9 pull-down as in (G), n=3, plotted as AURKA ratio +/− S.E.M, *p<0.05.

Decreased AURKA protein in NEDD9-deficient cells is caused by enhanced proteasome-dependent degradation

NEDD9 and AURKA undergo ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation in a cell cycle dependent manner (9, 20). To test if the decrease in AURKA protein levels is associated with increased proteasome-based degradation, cell lines with depleted NEDD9 were treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Fig.3C). Inhibition of proteasomal activity restored levels of AURKA in shNEDD9 cells to that of control cells (Fig.3C–D), suggesting that NEDD9 protects AURKA from ubiquitination and proteasome-dependent degradation. To directly test this, AURKA was immunoprecipitated from shNEDD9 and control cells and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-AURKA and anti-ubiquitin antibodies. Depletion of NEDD9 increased the amount of ubiquitinated AURKA (Fig.3E–F). Similar results were obtained with original MDA-MB-231 cells. Moreover, re-expression of wild type NEDD9 was able to rescue this phenotype and decrease ubiquitination of AURKA (Supplementary Fig.1E–F).

NEDD9-dependant decrease in AURKA ubiquitination could be caused by steric hindrance of bound NEDD9 or by titration of ubiquitination machinery components, since both proteins utilize the APC/C-cdh1 complex (8, 20). In order to distinguish between these two possibilities, the levels of other APC/C-cdh1 targets, including Plk1 and Cdk1 in shNEDD9 cells were evaluated by immunoblotting. No difference in Plk1 and Cdk1 expression was detected between shNEDD9 and controls cells (Supplementary Fig.1D), indicating that NEDD9 specifically targets AURKA and does not affect stability of other APC/C-cdh1 substrates. We have previously demonstrated that NEDD9 binds to the N-terminal domain of AURKA containing the A-box motif (19), which is required for cdh1 binding and ubiquitination by APC/C (7–8). To test this hypothesis, we used recombinant NEDD9, cdh1, and AURKA in in vitro GST pull-down assay and examined if presence of NEDD9 imposes its inhibitory action on cdh1 directly. We confirmed that NEDD9 was able to bind AURKA in vitro in the presence of excess cdh1 and titrated cdh1 from the complex with AURKA in a concentration dependant manner (Fig.3G–H). Thus, the presence of NEDD9 potentially increases AURKA protein levels by protecting AURKA from binding cdh1 resulting in reduced AURKA ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation.

NEDD9 binding to AURKA is necessary for protein stabilization

Phosphorylation of NEDD9 at S296 and S298 by AURKA impedes formation of the NEDD9/AURKA complex (19). To determine the impact of NEDD9 binding on AURKA protein levels, individual and dual phosphorylation null S296A-(A), S296A/S298A-(AA) and mimetic S296E-(E), S296E/S298E-(EE) forms of NEDD9 were generated. Indicated mutants were transfected in HEK293T cells followed by IP of AURKA (Fig.4A). Immunoprecipitation analysis demonstrated a reduction in binding to AURKA by the NEDD9 phosphomimetic (E, EE) mutants, whereas phosphorylation null (A, AA) NEDD9 mutants demonstrated increase in AURKA binding (Fig.4A–B), in agreement with our previously published observations (19). The increase in binding by phosphorylation null mutants in this setting is expected due to overexpression of NEDD9 in HEK293T cells and inability of AURKA/NEDD9-AA complex to dissociate. To test the ability of these mutants to rescue the levels of AURKA in shNEDD9 cells, the two NEDD9 mutants (AA, EE) were overexpressed in an inducible manner and AURKA levels were measured by western blotting (Fig.4C–D). Re-expression of the AA mutant was sufficient to restore the levels of AURKA protein, meanwhile, the EE mutant failed to restore the levels of AURKA to control levels due to its inability to bind AURKA. Therefore, binding of NEDD9 to AURKA is necessary to stabilize AURKA.

Figure 4. NEDD9 binding to AURKA is necessary for protein stabilization.

(A). WB analysis of AURKA and NEDD9 expression in WCL (left) or IP-GFP (right) from 293T cells transfected with pAcGFP-NEDD9-WT, AA, EE A, E, mutants or GFP-control. (B). Quantification of AURKA-coIP as in (A), n=3, plotted as percentage +/− S.E.M. AURKA-coIP with wtNEDD9 assigned 100%. Student’s t-test **p=0.0013, *p=0.010, **p=0.00209, ns (WT/AA, or /EE, or /A or /E respectively). (C). WB analysis of AURKA and NEDD9 expression in WCL of MDA-MB-231 cells expressing doxycycline-inducible NEDD9-AA, -EE or empty vector control. (D). Quantification of AURKA expression as in (C) n=3, relative intensity units (RIU) +/− S.E.M, normalized to actin. Two-way ANOVA, p<0.0001. Student’s t-test, **p=0.0063, 0.0061 (AA /EE (+Dox, 24, 48h)).

NEDD9 binding to AURKA decreases the efficacy of AURKA inhibitors in vitro and in in vivo xenografts

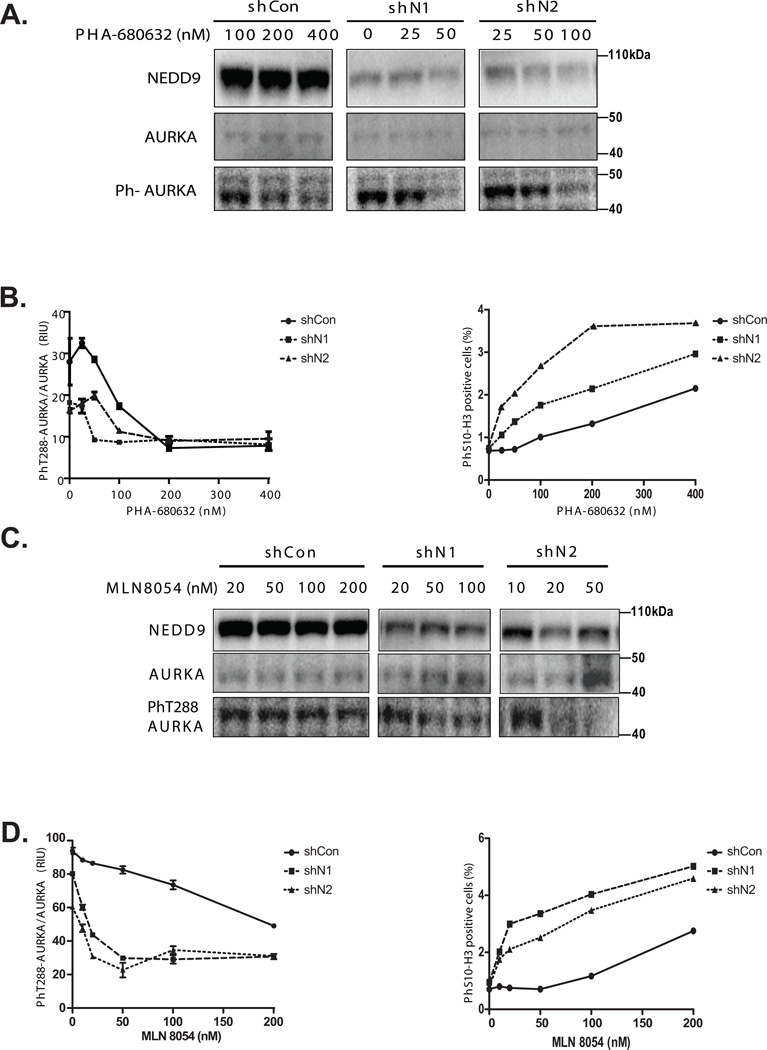

Due to the structural proximity of the ATP binding pocket to the NEDD9 binding domain on AURKA (23), we hypothesized that NEDD9-AURKA binding could potentially interfere with binding of AURKA inhibitors, in addition to preventing cdh1 binding. MLN8054 and PHA-680632 are ATP competitive AURKA inhibitors that are currently in Phase II clinical trials that have shown some efficacy against hematopoietic malignancies but have minimal effects against solid tumors (29–31). To evaluate the impact of NEDD9 expression on therapeutic outcome, NEDD9 was knocked down in breast cancer cell lines with high NEDD9 expression prior to treatment with PHA-680632 or MLN8054. NEDD9 depletion increased the efficacy of both inhibitors (Fig.5A), decreasing the IC50 of PHA-680632 from 150nM in control cells to 50–100nM in shNEDD9 cells (Fig.5B), as determined by the amount of active phT288-AURKA. Similar results were obtained with MLN8054, where the IC50 value decreased from 200nM (shCon) to 20nM (shNEDD9) (Fig.5C–D). Inhibition of AURKA function was further confirmed by analysis of histone H3 phosphorylation in treated shCon and shNEDD9 cells. Inhibition of AURKA leads to accumulation of cells in mitosis characterized by phosphorylation of histone H3 at Ser10 (Fig.5B, D, Supplementary Fig.2E). The concentration of PHA-680632 was limited to 400nM to avoid targeting AURKB which might lead to decrease in phosphorylation of histone H3.

Figure 5. NEDD9 binding to AURKA decreases the efficacy of AURKA inhibitors in vitro.

(A). WB analysis of AURKA, phT288-AURKA, NEDD9 in shCon or shNEDD9-MDA-MB-231LN cells treated with PHA-680632. (B). Quantification of phT288-AURKA expression as in (A) n=3, normalized to total AURKA and plotted as relative intensity units (RIU) +/− S.E.M. Two-way ANOVA, p<0.0001, (shCon/shN1 or shN2), p=0.0013 (shN1/shN2). Quantification of phS10-Histone H3 (IF), n=3, 1000 cells/treatment, p=0.006, p=0.0067 (shCon/shN1 or shN2), ns (shN1/shN2) (C). WB analysis of total AURKA, phT288-AURKA, NEDD9 expression in cells treated with increasing concentrations of MLN8054. (D). Quantification as in B for the western blots shown in (C), p<0.0001, (shCon/shN1 or shN2), p=0.0041 (shN1/shN2). Quantification of IF shown in Supplementary Fig.2E, n=3, 1000 cells/treatment, p=0.0053, P=0.0086 (shCon/shN1 or shN2), ns (shN1/shN2).

NEDD9 depletion alone or in combination with AURKA inhibitors reduces tumor burden and lung metastasis

To examine the validity of our findings in in vivo xenograft models of human breast cancer, we used MDA-MB-231LN cells and shRNAs targeting NEDD9 or control. Tumor cells were injected into the mammary fat pad of NSG female mice and the tumor growth was assessed using bioluminescence imaging (BLI) (Fig.6A–B). The original MDA-MB-231LN cell line was tested and showed similar NEDD9 expression, tumor growth and metastasis kinetics when compared to MDA-MB-231LN-shCon cells (Fig.6A–B, Supplementary Fig.1F). Based on these results we have concluded that the MDA-MB-231LN-shCon cell line is a proper control and we used it in the subsequent experiments. Depletion of NEDD9 alone reduced tumor burden by 15–20% (Fig.6B) and reduced the number of metastases in lungs by 25–50% (Fig.6D–E shCon-V, shN2-V, Supplementary Fig.2A).

Figure 6. Depletion of NEDD9 combined with AURKA inhibitors leads to decrease in a tumor burden and lung metastasis in breast cancer xenograft model.

(A). Representative images of bioluminescence (BLI) of mice orthotopically injected with MDA-MB-231LN parental, shCon or shNEDD9 (shN2) cells. (B). Quantification of BLI data as in (A) plotted as mean log photon flux +/−S.E.M. Linear regression analysis, p=0.0021, p=0.0006 (shCon/shN2), weeks 3 and 4; ns (shCon/parental). (C). Quantification of BLI data, mice orthotopically injected with shNEDD9 or shCon cells and treated with MLN8237 (MLN) or vehicle, 3 independent experiments, n=6 in each group; mean photon flux, +/−S.E.M. Two-way ANOVA, p=0.0061 (shCon-MLN/shN2-MLN, days 7–11). (D). Representative images of BLI, lungs dissected from 4 groups. (E). Quantification of BLI data as in (D), 3 independent experiments, n=6/group; mean photon flux +/−S.E.M. Two-way ANOVA, **p=0.0071 (shCon-Vehicle/shN2-Vehicle); **p=0.045 (shCon-MLN/shN2-MLN).

Next, we combined shNEDD9 and AURKA inhibitor (MLN8237-more stable analog of MLN8054) to test if the combination will increase the efficacy of MLN8237 against primary tumor and metastasis (Fig.6C–E). Treatment was initiated when primary tumor volume reached 150–200mm3, based on ultrasound measurements in each cohort (30). Representative images and quantification of tumor volume is shown in Supplementary Fig.2B–C. Difference in the rates of tumor growth among the 4 groups was assessed by BLI and pathology measurements using linear regression analysis with time, cell line, and treatment as covariates. Application of MLN8237 alone did not lead to a decrease in primary tumor growth, but in combination with shNEDD9, efficacy was improved two-fold (Fig.6C). Surprisingly, treatment with MLN8237 alone significantly decreased the number of lung metastases with a two-fold greater response in shNEDD9-expressing cells (Fig.6D–E, Supplementary Fig.2D).

Next, we utilized intravenous injection of breast cancer cells in NSG male mice to determine the impact of AURKA inhibitor on colonization by circulating tumor cells (CTC). Based on BLI data (Fig.7A–C) and study end point pathology reports on dissected lungs (supplemental Fig.2F), shNEDD9-expressing cells were extremely sensitive to MLN8237 and were not capable of initiating tumor growth in lungs when compared with vehicle-treated cells. In summary, depletion of NEDD9 sensitizes human xenografted tumors and CTCs to AURKA inhibitors and eliminates metastasis to the lungs. Collectively, our data suggest a model (Fig.7D) in which overexpression of NEDD9 renders AURKA less susceptible to Cdh1-APC mediated ubiquitination and binding of small molecule ATP competitive inhibitors, thus protecting it from degradation and drug applications.

Figure 7. Combination of AURKA Inhibitors with depletion of NEDD9 reduces colonization potential of human circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in lungs.

(A). Representative images of BLI; mice intravenously injected with MDA-MB-231LN cells expressing shCon or shNEDD9(shN2) and treated with MLN8237 (M) or vehicle (V). (B). Quantification of BLI data as in (A), 3 independent experiments, n=6/group, plotted as fold growth of BLI mean radiance, +/−S.E.M. Two-way ANOVA p<0.0001 (shCon-V/shCon-M), (shN2-V/shN2-M), (shCon-V/shN2-V); p=0.0145 (shCon-M/shN2-M). (C). Quantification of BLI as in (A), dissected lungs; 3 independent experiments, n=6/group, mean photon flux +/−S.E.M. One-tailed Student’s t-test p<0.0001 (shCon-V/shCon-M), (shN2-V/shN2-M), p=0.009 (shCon-V/shN2-V), p=0.0335 (shCon-M/shN-M). (D). Model of NEDD9 action on AURKA stability and inhibitors competitive binding: I/III. Under normal physiological conditions with low NEDD9 expression, AURKA is not solely bound to NEDD9 and gets targeted by cdh1 and AURKA inhibitors; II/IV. Overexpression of NEDD9 leads to sequestering of AURKA by NEDD9 and limits cdh1 binding thus stabilizing AURKA and hampers the ability AURKA inhibitors to access ATP packet.

Discussion

Recent studies corroborate overexpression of NEDD9 specifically with breast cancer and melanoma metastasis (16–18). Our data indicate that NEDD9 expression levels correlate positively with oncogenic AURKA expression and activation. Both proteins were correlated with pathological parameters in human breast cancer cell lines and breast cancer patient samples. Moreover, achieving an 80% accuracy for predicting cancer stage invasiveness is possible when screening for expression of both proteins.

AURKA inhibitors have recently entered Phase II clinical trials for cancer treatment. However, the best response achieved in advanced tumors is disease stabilization, as tumor regression has not been reported (29–32). The knowledge of the molecular factors that influence AURKA stability and therefore, sensitivity and resistance to AURKA inhibitors remains limited. With a few exceptions, such as, TPX2 and PUM2 (13–14), the role of AURKA activators in the stability of AURKA and their impact on sensitivity to AURKA inhibitors is unknown.

We show here that NEDD9 is a critical component in AURKA activation and stability. Furthermore, the molecular mechanism by which NEDD9/AURKA signaling functions to increase breast tumor cell resistance to AURKA inhibitors has been elucidated. Overexpression of NEDD9 in breast cancer cells prevents proteolytic degradation of AURKA and results in upregulation of AURKA protein level. AURKA activation correlates with protein stabilization, which in turn directly depends upon APC/C complex and its substrate recognition subunit, cdh1. Direct binding of NEDD9 to AURKA hampers the ability of the APC/C complex to ubiquitinate AURKA by preventing cdh1 binding. A NEDD9-dependent increase in AURKA protein and activity is critical for G2/M transition. Interestingly, that majority of proteins activating and/or stabilizing AURKA reside in the nucleus (Bora, TPX2, Ajuba, ect.) or require prior modifications (TPX2/AURKA binding is stimulated by the GTPase Ran) including phosphorylation by AURKA for binding (33–36). Nevertheless, a NEDD9-driven increase in the total amount of AURKA would be less noticeable in mitosis due to the inactivity of cdh1 (8). The excess of NEDD9 protein might promote the binding of known AURKA partners such as Ajuba, TPX2 and Bora (33–34) leading to increased loading of AURKA on microtubules and Plk1 activity (37) and cancer progression. Direct binding of NEDD9 at the N-terminal domain decreases the efficacy of AURKA inhibitors in cell culture and in mammary tumor xenografts. Deletion or mutation of NEDD9, dramatically decreases AURKA protein level and kinase activity. Phosphorylation of NEDD9 by AURKA at Ser296 serves as a negative feedback loop to regulate the levels of active AURKA. The abundance of NEDD9 in epithelial cancers and dephosphorylation by PP2A (38) creates a constant supply of unphosphorylated NEDD9 which would stabilize and activate AURKA. We found that depletion of NEDD9 reduces tumor cell proliferation and lung metastases of orthotopic human tumor xenografts. Finally, we have established that treatment with AURKA inhibitors is particularly efficient against metastasis. In combination with shNEDD9 RNAs, MLN8237 abolishes lung metastases from orthotopic xenograft models as well as in lung colonization assays. No significant changes in animal weight and no apparent toxicity were noticed, suggesting a favorable toxicity profile.

The correlation of AURKA and NEDD9 expression in cancer patient biopsies could be critical for diagnostic purposes. It could potentially be used to predict the sensitivity of these patients to AURKA inhibitors. In addition, our results advocate the development and investigation of new NEDD9 targeting compounds as a novel therapeutic strategy against metastatic breast cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Erica Peterson, Sherry Skidmore, Lana Yoho, Dr. Michael Schaller, and Dr. Scott Weed (WVU, USA) for critically reading the manuscript and outstanding administrative support, Dr. Erica Golemis (FCCC, USA) for tissue sections, IHC NEDD9 KO mice, WVU Tissue Bank and Animal Facility. Animal Models & Imaging Facility has been supported by the MBRCC and NIH grants P20 RR016440, P30 RR032138/GM103488 and S10RR026378. Flow Cytometry Facility was supported by NIH grants P30GM103488, P30RR032138 and RCP1101809. This work was supported by a grant from NIH-NCI (CA148671 to E.N.P), Susan G. Komen for Cure Foundation (KG100539 to E.N.P, KG110350 to A.V.I) and in part by NIH/NCRR (5 P20 RR016440-09 to MBRCC).

Financial support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number CA148671 and the Susan G. Komen for Cure Foundation KG100539 (to E.N.P.). Small animal imaging and image analysis were performed in the West Virginia University Animal Models & Imaging Facility, which has been supported by the Mary Babb Randolph Cancer Center and NIH grants P20 RR016440 and P30 RR032138/GM103488.

Footnotes

Disclaimers:

The authors declare the following: 1. This manuscript contains original work only, 2. All authors have directly participated in the planning, execution and analysis of this study, 3. All have approved the submitted version of this manuscript, 4. The described data has not been published nor submitted elsewhere.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions. R.J.I and E.N.P conceived the project and wrote the manuscript. TMA statistical analysis was performed by E.R.E and M.V.C. Animal pathology and tumor analysis was done by R.H.L. All remaining experiments and data analysis were performed by S.L.M, R.J.I and E.N.P.

References

- 1.Zhou H, Kuang J, Zhong L, Kuo WL, Gray JW, Sahin A, et al. Tumour amplified kinase STK15/BTAK induces centrosome amplification, aneuploidy and transformation. Nat Genet. 1998;20:189–193. doi: 10.1038/2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sen S, Zhou H, White RA. A putative serine/threonine kinase encoding gene BTAK on chromosome 20q13 is amplified and overexpressed in human breast cancer cell lines. Oncogene. 1997;14:2195–2200. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bischoff JR, Anderson L, Zhu Y, Mossie K, Ng L, Souza B, et al. A homologue of Drosophila aurora kinase is oncogenic and amplified in human colorectal cancers. EMBO J. 1998;17:3052–3065. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nadler Y, Camp RL, Schwartz C, Rimm DL, Kluger HM, Kluger Y. Expression of Aurora A (but not Aurora B) is predictive of survival in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4455–4462. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agnese V, Bazan V, Fiorentino FP, Fanale D, Badalamenti G, Colucci G, et al. The role of Aurora-A inhibitors in cancer therapy. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:vi47–vi52. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka T, Kimura M, Matsunaga K, Fukada D, Mori H, Okano Y. Centrosomal kinase AIK1 is overexpressed in invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2041–2044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taguchi Si, Honda K, Sugiura K, Yamaguchi A, Furukawa K, Urano T. Degradation of human Aurora-A protein kinase is mediated by hCdh1. FEBS Lett. 2002;519:59–65. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02711-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Floyd S, Pines J, Lindon C. APC/C(Cdh1) Targets Aurora Kinase to Control Reorganization of the Mitotic Spindle at Anaphase. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1649–1658. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crane R, Kloepfer A, Ruderman JV. Requirements for the destruction of human Aurora-A. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5975–5983. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tyers M, Jorgensen P. Proteolysis and the cell cycle: with this RING I do thee destroy. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:54–64. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zachariae W. Progression into and out of mitosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:708–716. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.A. Shi Y, Solomon LR, Pereda-Lopez A, Giranda VL, Luo Y, Johnson EF, et al. Ubiquitin-specific cysteine protease 2a (USP2a) regulates the stability of Aurora-A. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:38960–38968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.231498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giubettini M, Asteriti IA, Scrofani J, De Luca M, Lindon C, Lavia P, et al. Control of Aurora-A stability through interaction with TPX2. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:113–122. doi: 10.1242/jcs.075457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang YH, Wu CC, Chou CK, Huang CY. A translational regulator, PUM2, promotes both protein stability and kinase activity of Aurora-A. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson EO, Chang KH, Ghosh S, Venkatesh C, Giger K, Low PS, et al. LIMK2 is a crucial regulator and effector of Aurora-A-kinase-mediated malignancy. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1204–1216. doi: 10.1242/jcs.092304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minn AJ, Gupta GP, Siegel PM, Bos PD, Shu W, Giri DD, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436:518–524. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minn AJ, Gupta GP, Padua D, Bos P, Nguyen DX, Nuyten D, et al. Lung metastasis genes couple breast tumor size and metastatic spread. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6740–6745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701138104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim M, Gans JD, Nogueira C, Wang A, Paik JH, Feng B, et al. Comparative oncogenomics identifies NEDD9 as a melanoma metastasis gene. Cell. 2006;125:1269–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pugacheva EN, Golemis EA. The focal adhesion scaffolding protein HEF1 regulates activation of the Aurora-A and Nek2 kinases at the centrosome. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:937–946. doi: 10.1038/ncb1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nourry C, Maksumova L, Pang M, Liu X, Wang T. Direct interaction between Smad3, APC10, CDH1 and HEF1 in proteasomal degradation of HEF1. BMC Cell Biol. 2004;5:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-5-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng M, McKeown-Longo PJ. Cell adhesion regulates Ser/Thr phosphorylation and proteasomal degradation of HEF1. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:96–103. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carpinelli P, Ceruti R, Giorgini ML, Cappella P, Gianellini L, Croci V, et al. PHA-739358, a potent inhibitor of Aurora kinases with a selective target inhibition profile relevant to cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:3158–3168. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soncini C, Carpinelli P, Gianellini L, Fancelli D, Vianello P, Rusconi L, et al. PHA-680632, a novel Aurora kinase inhibitor with potent antitumoral activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4080–4089. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoar K, Chakravarty A, Rabino C, Wysong D, Bowman D, Roy N, et al. MLN8054, a small-molecule inhibitor of Aurora A, causes spindle pole and chromosome congression defects leading to aneuploidy. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4513–4525. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02364-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dees EC, Infante JR, Cohen RB, O'Neil BH, Jones S, von Mehren M, et al. Phase 1 study of MLN8054, a selective inhibitor of Aurora A kinase in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;67:945–954. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1377-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pugacheva EN, Jablonski SA, Hartman TR, Henske EP, Golemis EA. HEF1-dependent Aurora A activation induces disassembly of the primary cilium. Cell. 2007;129:1351–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruijter JM, Pfaffl MW, Zhao S, Spiess AN, Boggy G, Blom J, et al. Evaluation of qPCR curve analysis methods for reliable biomarker discovery: Bias, resolution, precision, and implications. Methods. 2012;pii:S1046–S2023. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.08.011. (12)00229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pugacheva EN, Golemis EA. HEF1-aurora A interactions: points of dialog between the cell cycle and cell attachment signaling networks. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:384–391. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.4.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maris JM, Morton CL, Gorlick R, Kolb EA, Lock R, Carol H, et al. Initial testing of the aurora kinase A inhibitor MLN8237 by the Pediatric Preclinical Testing Program (PPTP) Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55:26–34. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manfredi MG, Ecsedy JA, Chakravarty A, Silverman L, Zhang M, Hoar KM, et al. Characterization of Alisertib (MLN8237), an investigational small-molecule inhibitor of aurora A kinase using novel in vivo pharmacodynamic assays. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7614–7624. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manfredi MG, Ecsedy JA, Meetze KA, Balani SK, Burenkova O, Chen W, et al. Antitumor activity of MLN8054, an orally active small-molecule inhibitor of Aurora A kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4106–4111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608798104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kasap E, Boyacioglu SO, Korkmaz M, Yuksel ES, Unsal B, Kahraman E, et al. Aurora kinase A (AURKA) and never in mitosis gene A-related kinase 6 (NEK6) genes are upregulated in erosive esophagitis and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Exp Ther Med. 2012;4:33–42. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirota T, Kunitoku N, Sasayama T, Marumoto T, Zhang D, Nitta M, et al. Aurora-A and an interacting activator, the LIM protein Ajuba, are required for mitotic commitment in human cells. Cell. 2003;114:585–598. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00642-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hutterer A, Berdnik D, Wirtz-Peitz F, Zigman M, Schleiffer A, Knoblich JA. Mitotic activation of the kinase Aurora-A requires its binding partner Bora. Dev Cell. 2006;11:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsai MY, Wiese C, Cao K, Martin O, Donovan P, Ruderman J, et al. A Ran signalling pathway mediated by the mitotic kinase Aurora A in spindle assembly Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:242–248. doi: 10.1038/ncb936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan EH, Santamaria A, Silljé HW, Nigg EA. Plk1 regulates mitotic Aurora A function through βTrCP-dependent degradation of hBora. Chromosoma. 2008;117:457–469. doi: 10.1007/s00412-008-0165-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macurek L, Lindqvist A, Medema RH. Aurora-A and hBora join the game of Polo. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4555–4558. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng M, McKeown-Longo PJ. Cell adhesion regulates Ser/Thr phosphorylation and proteasomal degradation of HEF1. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:96–103. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.