Abstract

Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM) is the most aggressive brain tumor characterized by intratumoral heterogeneity at cytopathological, genomic and transcriptional levels. Despite the efforts to develop new therapeutic strategies the median survival of GBM patients is 12−14 months. Results from large-scale gene expression profile studies confirmed that the genetic alterations in GBM affect pathways controlling cell cycle progression, cellular proliferation and survival and invasion ability, which may explain the difficulty to treat GBM patients. One of the signaling pathways that contribute to the aggressive behavior of glioma cells is the protein kinase C (PKC) pathway. PKC is a family of serine/threonine-specific protein kinases organized into three groups according the activating domains. Due to the variability of actions controlled by PKC isoforms, its contribution to the development of GBM is poorly understood. This review intends to highlight the contribution of PKC isoforms to proliferation, survival and invasive ability of glioma cells.

Keywords: GBM, PKC, TMZ, glioblastoma multiforme, glioma, protein kinase C, signaling pathway, temozolomide

Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common and biologically aggressive type of astrocytoma, composed by poorly differentiated neoplastic astrocytes that present heterogeneity at the transcriptional and genomic levels. Despite recent therapeutic advances the median survival time for GBM patients remains approximately 12−14 mo.1-4

Several factors contribute to the reduced efficacy of treatment in GBM: (1) the existence of the blood-brain barrier that limits the delivery of therapeutic agents, in fact, several alkylating agents were used (carmustine, BCNU, lomustine) but patients developed toxicity due to the high doses used to achieved adequate concentrations in central nervous system (CNS); (2) the diffuse infiltration of the tumor into the surrounding brain, making total ablastic tumor resection impossible; (3) the existence of a population of brain resident cells that expresses stem cell properties that have tumorigenic properties and (4) tumor cell characteristics such as uncontrolled cellular proliferation, propensity for necrosis, angiogenesis, genomic instability and resistance to apoptosis.5-7

The best treatment currently available consists of cytoreductive surgery, followed by simultaneous radiation and chemotherapy and then chemotherapy alone.8-11 Standard chemotherapy consists in alkylating drug regimens, being temozolomide (TMZ) considered the gold standard of GBM treatment after a randomized study performed by Stupp et al.2,3,8,12-14 The limited success of TMZ in GBM treatment appears to be related to the occurrence of chemoresistance and to the inability of TMZ to induce tumor cell death.12-14 Previous studies, indicated that the resistance to the treatment could be modulated by the action of the O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) and/or by the mismatch repair (MMR) system15 and also by the ability of glioma cells to activate different survival signaling pathways.4,16,17 Recent studies showed that in TMZ-treated GBM cells only a reduced percentage of cells underwent apoptosis and also that there is an increased expression of light chain 3 (LC3), an autophagy-associated protein that may contribute to maintain glioma cells in a quiescent life during chemotherapy.16-18 In addition, it was also reported that the phosphorylation status of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate/serine-threonine kinase (Pi3K/AKT) and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK1/2 MAPK), which is significantly increased as compared with that in control cells, was maintained during the treatment with TMZ, suggesting that these signaling pathways may also contribute to glioma cells escape from TMZ-induced cell death.4,17,19,20

The activation of protein kinases is associated to molecular abnormalities that characterized GBMs. Primary GBMs typically harbor amplification and/or a high rate of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation, cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A/p16), deletion in chromosome 9p and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) deletion in chromosome 10. The most common EGFR mutant type—variant 3 (EGFRvIII)—is an in-frame deletion of exons 2–7 that due to the receptor autophosphorylation turns the EGFR-mediated signal-transduction pathway constitutively active.21,22 Upon autophosphorylation, several signal transduction pathways downstream of EGFR become activated such as the Ras/Raf/MAPK pathway, the PI3K/Akt pathway, the signal transduction and transcription activator (STAT), the protein kinase C (PKC) among others.22,23 Activation of PKC is one of the earliest events in a cascade that controls a variety of cellular responses, including gene expression, cell proliferation, survival and migration. Since the activation and regulation of the PKC activity is complex and depends on cell type and on stimuli the contribution of PKC isoforms to the gliomagenesis is not clear.

PKC Structure and Classification

Protein kinase C is a serine.threonine that belongs to the PKC family and was initially classified as lipid-sensitive enzyme since it was first identified as a receptor for diacylglycerol (DAG).23-25 The PKC isoforms are members of the AGC (cAMP-dependent, cGMP-dependent and protein kinase C) family of protein kinases that contains a highly conserved catalytic domain and a regulatory domain responsible for the maintenance of the enzyme in an inactive conformation. These kinases contain four homologous domains termed C1, C2, C3 and C4. Localized between the homologous domains it is possible to identify the variable domains V1, V2, V3, V4 and V5 domain, which are accessible to proteolytic cleavage upon activation and conformational change of PKC. Cleavage at the variable domains leads to the release of a constitutively active catalytic domain.23,26-28

According to the activating domains, PKC isoforms were organized into three groups: (1) the classical isoforms α, βI, βII, γ, (2) the novel PKC isoforms δ, ε, θ, η, μ and (3) the atypical PKC isoforms ι/λ and ζ (Table 1).28-31

Table 1. Classification of PKC.

| Isoforms | Activity | |

|---|---|---|

|

Classical isoforms |

α, βI, βII, γ |

Dependent on DAG, PS and Ca2+ |

|

Novel PKC isoforms |

δ, ε, θ, η, μ |

Bind DAG but are calcium independent |

| Atypical PKC isoforms | ι/λ and ζ | Bind PIP3 or ceramide but are calcium-independent and do not require DAG |

The classical (or conventional) PKC isoforms (cPKC) are dependent on DAG and phosphatidylserine (PS) that bind C1 domain and also on calcium since C2 domain binds anionic lipids in a Ca2+-dependent manner. The C3 region contains the catalytic site and the ATP-binding site, and the C4 region appears to be necessary for recognition of the substrate to be phosphorylated (Table 1).29,32-36

The novel PKC isoforms (nPKC) bind DAG through C1 domain, but are calcium independent since they have a C2 domain variant that is unable to link Ca2+, however their affinity for DAG is two orders of magnitude higher than that for the cPKCs (Table 1).28,37-39

The atypical PKC isoforms (aPKC) are calcium-independent and do not require DAG for activation since they contain a variant of the C1 domain that binds PIP3 or ceramide (not DAG or PMA). Nevertheless, the aPKC are characterized by a protein-protein interaction PB1 (Phox and Bem 1) domain that mediates interactions with other PB1-containing scaffolding proteins including p62, partitioning defective-6 (PAR-6) and MAPK, which modulates mitogen-activated protein kinase 5 (MEK5).37,40-42 · The human PKCι and mouse PKCλ are orthologs with 98% overall amino acid sequence identity and thus are referred to as PKCι/λ (Table 1).31

PKC Expression and Subcellular Localization

Regarding PKC isoforms expression, previous studies reported that most of the isoforms are ubiquitous and many cells coexpress multiple PKC isoforms. Nevertheless, there are some exceptions: PKC γ has been shown to be specifically expressed in neuronal tissue, whereas PKCβ is preferentially expressed in pancreatic islets, monocytes and brain, and PKCθ is expressed primarily by skeletal muscle, lymphoid organs and hematopoietic cell lines.28,37-39,41,43

The subcellular localization of PKC isoforms differs with the activation status. When PKCs are inactive they localize in the cytoplasm, but after activation PKC isoforms translocate to the plasma membrane, cytoplasmic organelles or nucleus.

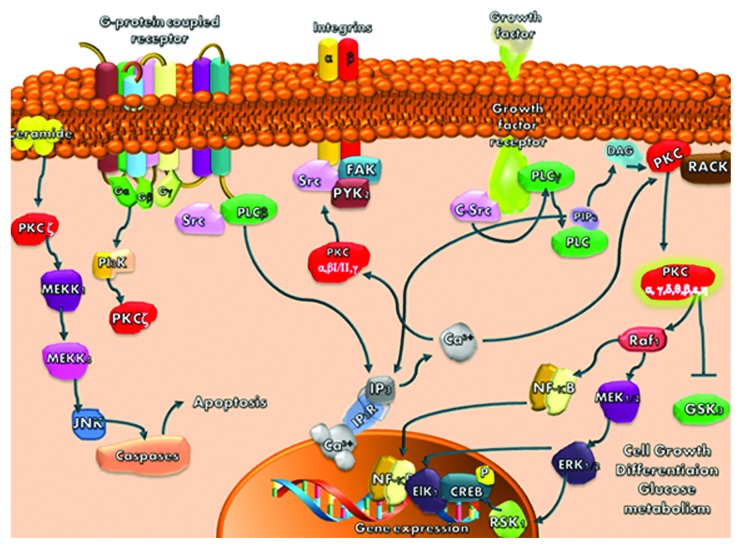

Translocation of PKCα, β, δ, ε and ζ to plasma membrane, mitochondria, Golgi, nucleus or perinuclear regions results in regulation of mitosis, cell survival pathways, apoptosis, cell to cell adhesion and migration, (Fig. 1).28,37, 39,41,43

Figure 1. PKC isoforms signaling pathways

The PKCs that rest in the cytosol interact with several proteins, including receptors for activated C kinase (RACKS), the product of the par-4 gene, zeta-interacting protein and lambda-interacting protein. PKCs may also phosphorylate specific PKC substrates such as the myristoylated alanine-rich PKC substrate (MARCKS) protein and pleckstrin contributing to remodelling the actin cytoskeleton, Figure 1.28,30

In addition, PKC could translocate to specialized membrane compartments such as lipid rafts (sphingolipid-/cholesterol-enriched plasma membrane) that form ceramide or caveolae (sphingolipid-/cholesterol-enriched detergent-resistant membrane), (Fig. 1).30,37,43

Mechanism of PKC Activation

The initial results based on the study of PKCα, reported that after the activation of growth factor receptors, there was activation of the phospholipase C (PLC) signaling pathway.26,28 Upon PLC activation, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) is hydrolyzed, DAG and inositol trisphosphate (IP3) are generated, cytoplasmatic Ca2+ concentration increases, Ca2+ interacts with C2 domain of PKCα and increases its affinity for the membrane.22,29,30 Once anchored to membrane, PKCα diffuses within the plane of the lipid bilayer and interacts with a secondary C1A domain which involves DAG and PS. Due to this interaction PKCα establishes a high-affinity binding to membrane and suffers a conformational change that expels the autoinhibitory pseudosubstrate domain from the substrate-binding pocket allowing PKC activation. When activated, PKC could be translocated from one intracellular compartment to another, thus being able to affect cellular processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, tumor promotion and neuronal activity, (Fig. 1).26,28,37,41

This mechanism explains the activation of the cPKC, but it is not enough to explain the activation of PKC isoforms that are independent of calcium and even in cPKC isoforms there are some variations in the activation mechanism. Subsequent studies reported that activation of PKC could be achieved by several other mechanisms: (1) phosphorylations on both serine/threonine and tyrosine residues that influence the stability; (2) cleavage by caspases, generating a catalytically active kinase domain and a free regulatory domain fragment that can act both as an inhibitor of the full-length enzyme and as an activator of certain signaling responses and (3) activation by lipid cofactors (such as ceramide or arachidonic acid) or through lipid-independent mechanisms (such as oxidative modifications or tyrosine nitration) that allows PKC signaling throughout the cell, not just at DAG containing membranes. There is also the possibility to activate PKC pharmacologically using tumor-promoting phorbol esters such as phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) or 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate (TPA), which induce the translocation of PKCα and PKCδ from the cytosol to the plasma membrane and nucleus and of PKCε to the Golgi membranes (Table 2).29,31,39,43,46

Table 2. Mechanisms of PKC activation.

| Mechanisms of PKC activation | PKC isoforms |

|---|---|

| Dependent on DAG and Ca2+ |

Classical isoforms: α, βI, βII, γ |

| Phosphorylations on both serine/threonine and tyrosine residues |

Classical isoforms: α, βI, βII, γ Novel PKC isoforms: δ, ε, θ, η, μ |

| Cleavage by caspases |

Novel PKC isoforms: δ, θ, ε, Atypical PKC isoform: ζ |

| Activation by lipid cofactors or by lipid-independent mechanisms | Novel PKC isoforms: δ Atypical PKC isoform: ζ |

Activation of PKC through C-terminal phosphorylation allows the enzyme to achieve a favorable conformation to catalysis since phosphorylation of the threonine residue introduces a negative charge that aligns residues in the catalytic pocket and stabilizes the active conformation of the enzyme. After the first phosphorylation cPKCs and nPKCs undergo two other autophosphorylation reactions that stabilize the enzyme. The aPKCs contain a phosphomimetic Glu in place of the phosphorylatable hydrophobic motif Ser/Thr residue and do not require this processing mechanism.26,28

Regarding the PKC activation by caspase, previous studies reported that only PKCδ, PKCθ, PKCε and PKCζ undergo caspase-dependent cleavage in response to a range of apoptogenic stimuli; the atypical PKCλ and -ι isoforms do not appear to be regulated by caspases since they lack caspase cleavage sites.26,28 The caspase-dependent cleavage occurs at the hinge region and allows the release of a catalytic domain, which in PKCε is catalytically active but in PKCζ is catalytically inactive. The differences in activity of the release domain could be related to the phosphorylation of Ser/Thr residues but further studies will be need to clarify the caspase activation of PKC.26,28

Regarding the contribution of lipid cofactors such as ceramide to PKC activation, it was reported that PKCδ may activate acid sphingomyelinase (ASM), the enzyme which catalyzes the hydrolysis of sphingomyelin to form ceramide at the plasma membrane. The accumulation of ceramide at the plasma membrane has two effects: provides a nonspecific mechanism to localize signaling proteins such as PKCs to membrane rafts and leads to the recruitment and activation of PKCζ.28,44,45

Independently of the activation mechanism, after activation PKC may phosphorylate downstream targets and posteriorly it could be downregulated by ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation.24,26,28 In this regard, it has been demonstrated that the PH domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase (PHLPP) regulates the dephosphorylation step that precedes the downregulation of PKC. This process represents the termination of the life cycle of conventional and novel PKC isoenzymes. In the absence of chronic stimulation, these PKC isoforms have a long half-life.24,26,28

PKC Contribution to Tumor Development

The first evidence showing the involvement of PKC in tumorigenesis came from the discovery that tumors induced by phorbol esters were associated to the activation of PKC. After that, recent studies showed that PKC isoforms may regulate signaling pathways involved in cellular proliferation, survival and migration and also signaling pathways involved in chemoresistance such as the Pgp 170 pathway.22,24,26,28,46,47 Although, there are some studies reporting that several isoforms of PKC may act as tumor suppressors since they can activate pro-apoptotic pathways.26,28,34

Regarding PKCα several studies reported that this PKC isoform is overexpressed in tissue samples of prostate, endometrial and high-grade urinary bladder tumors and also that its activation contributes to cell proliferation and migration and therefore to tumor progression.33,48-50 Moreover, it was showed that in intestinal, pancreatic and mammary cells PKCα has anti-proliferative effects. In fact, it was shown that treatment of intestinal cells with PMA causes cell-cycle arrest in G1 in a PKCα-dependent manner and deletion of PKCα promoted polyp formation in wild-type mice.34,48 In breast cancer, several studies showed that overexpression of PKCα in MCF-7 cells contributes to increase the ability of tumor cells to metastasis. Thus, regarding breast cancer there is evidence for a promoting and a suppressing role for PKCα.51 In addition, it was also reported that after PKCα activation by phorbol ester tumor-promoters, there was stabilization of F-actin and inactivation of E-cadherin, highlighting the role of PKCα in the regulation of cell to cell contact (Fig. 1).50

The activation of PKCβ seems to contribute to colon carcinogenesis since increased expression of PKCβ was observed in both aberrant crypt foci and colon tumors, as compared with normal colonic epithelium.43 Consistent with this, mice lacking PKCβ have increased resistance to AOM (azoxymethane)-induced colon tumorigenesis and treatment with a PKCβ-specific inhibitor decreased colon tumor formation in AOM-treated mice (Table 3).35

Table 3. Role of PKC isoforms in tumor development.

| PKC isoforms | Tumor Suppressor | Tumor promoter |

|---|---|---|

| PKC α |

Intestinal, pancreatic and breast tumor cells |

Prostate, endometrial, breast, glioma and high-grade urinary bladder tumor cells |

| PKC β |

|

Colon and glioma tumor cells |

| PKCδ |

Lung adenocarcinoma and glioma cells |

Breast and glioma tumor cells |

| PKCε |

|

Bladder, brain, breast, skin, head, neck, glioma thyroid, liver, lung and prostate tumor cells |

| PKCη |

NIH3T3 cells and keratinocytes |

MCF-7 and GBM |

| PKC ζ |

Ovarian tumor cells |

Hematopoietic, breast and pancreatic tumor cells |

| PKCι/λ | Leukemia, breast, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, pancreatic, glioma prostate, colon and NSCLC tumor cells |

The PKCδ isoform has been associated to tumorigenesis in human breast cancer since McKiernan et al. found an association between elevated PKCδ mRNA and poor outcome.52 However, other results also reported that activation of PKCδ by caspase induces DNA fragmentation contributing to activation of proapoptotic signaling pathway, indicating that PKCδ may also function as a tumor suppressor. In fact, it was observed that activation of PKCδ causes proliferation defects in G1 and G2 phases of the cell cycle through the modulation of cyclin expression or modulation of cyclin dependent kinases activity.47 In accordance with the tumor suppressor hypothesis, recent studies showed that in phorbol-ester treated lung adenocarcinoma cells, the activation of PKCδ induced G1 arrest.53 The reason for the dual behavior of PKCδ it is not known, but Steinberg et al. hypothesize that it could be due to differential tyrosine-phosphorylation status (Table 3).38

Moreover, PKCε was associated to tumor development and is considered the isoform with the highest carcinogenic potential of all PKC isoforms. Overexpression of PKCε was detected in several tumors such as: bladder, brain, breast, skin, head, liver, thyroid, neck, lung and prostate.25,46,54-56 The studies initially performed by Mischaks et al. showed that the activation of PKCε increased the proliferation of NIH 3T3 fibroblasts and also that all mice injected with these cells overexpressing PKCε developed tumors.57 Further studies showed that PKCε activated the Ras/Raf/MAPK pathway and through it activated the cyclin D1 promoter inducing an increased proliferation. PKCε may also exert its effects through the modulation of anti-apoptotic signaling pathways such as caspases and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) family members and through the modulation of survival pathways such as AKT/protein kinase B(PKB).25,54 Furthermore, Pan et al. demonstrated that silencing PKCε decreased in vitro invasion and motility as well as incidence of lung metastases in a pre-clinical animal model. In agreement with this results, Toton et al. showed that zapotin, which selectively activates PKCε leading to its downmodulation, was associated to an increased percentage of apoptotic cells and a decreased in cell migration (Table 3), (Fig. 1).37,55 , 56

In addition, the activity of the PKCη isoform was associated with increased proliferation of MCF-7 and of GBM cells but other studies reported that the increased activity of this PKC isoform induced cell cycle arrest in NIH3T3 cells and keratinocytes.58-60

The atypical PKC, PKC ζ and ι/λ have been also implicated in tumorigenesis. However, the role of PKCζ is less understood and more controversial. Previous studies reported that PKCζ stimulates motility and maturation of human CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and may also stimulates motility of human MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells and pancreatic cancer cells. Although, Nazarenko et al. reported that PKC ζ exhibits a proapoptotic function in ovarian cancer (Table 3).57,61

On the other hand, PKCι/λ plays an active role in tumorigenesis of many cancers such as leukemia, breast cancer, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, pancreatic, prostate, colon cancer and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).62-66 Upon activation PKCι/λ may regulate several signaling pathway such as calpains, nuclear factor- kinase B (NFκB), MAPk, controlling invasion, tumor growth, survival and chemoresistance.64

Role of PKC in Glioblastoma Multiforme

Among the years, many studies have been made to achieve an adequate treatment for GBM and to find molecular targets in order to control cellular proliferation, diffuse infiltration, propensity for necrosis, angiogenesis and resistance to apoptosis of glioma cells.1,16,29,67,68 Several signaling pathways were pointed as therapeutic targets such as EGFR, PI3K/AKT/ mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), Ras/MEK/MAP kinase and PKC among others.1,67,68 Due to the variability of actions controlled by PKC isoforms, the contribution of this kinase family to the development of GBM is poorly understood.

The PKCα exerts a pro-mitotic and pro-survival effect in glioma cell lines and loss of PKCα was associated with an increased sensitivity to a variety of apoptotic stimuli.36 It was also reported that PKCα contributes to cell proliferation in head and neck cancer cell lines and could be used as a predictive biomarker for disease-free survival in head and neck cancer patients.69 The mechanism by which PKCα contributes to the glioma cell proliferation seems complex since it involves different signaling mechanisms. Fan et al. demostrated that in glioma cells an AKT-independent, PKCα dependent mechanism links PI3K with mTORC1, which is required for malignant glioma formation.20 On the other hand, mTORC2, which is activated by PI3K, has as substrate PKCα and therefore the activation of PKCα is also dependent on AKT activation.56,69 In addition, it was described that in glioma cells, PKCα isoform is the main modulator of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway, which is required for the constitutive expression of the basic fibroblast growth factor, a potent mitogen for glioma cell growth.16,70 Furthermore, Mut et al. reported that PKCα induced phosphorylation of NFκB/p65 which is a pro-survival and proliferative factor.71 Hu et al. also reported that phosphorylation of PKCα is a prerequisite for regulating C6 cell migration indicating that PKCα contributes not only to the survival and proliferation of glioma cells but also to the motility of these tumor cells.33 In agreement with these observations are the results presented by Kohutek et al. who showed that PKCα regulates N-cadherin cleavage which is involved in cell migration.72 Taking together these results show that PKCα is involved in survival, proliferation and migration of glioma cells.

Regarding PKCβ it was reported that this isoform was involved in vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) signaling, which is important in glioma angiogenesis. Furthermore, PKCβ interacts with the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)/PI3K/AKT pathway, contributing to increase the proliferation and the resistance to apoptosis of glioma cells. Due to the fact that PKCβ could contribute to angiogenesis, proliferation and survival of glioma cells, several studies using specific inhibitors were performed in vitro. Enzastaurin (LY317615) is a selective inhibitor of PKCβ that in in vitro studies induced a significant reduction of glioma cell proliferation.47,73 However, when enzastaurin was tested in a randomized phase III trial, in patients with recurrent GBM, the results were disappointing, indicating that other pathways than PKCβ contribute to the aggressive behavior of gliomas.74

As previously described, PKCδ acts as a pro or anti-apoptotic kinase depending on the cell type, on the apoptotic stimulus and on the phosphorylated tyrosine residues. In glioma cells, the results are also different and depend on the phosphorylation site. Therefore, Okhrimenko et al. reported that phosphorylation of PKC δ on tyrosine 155 protected glioma cells from the apoptosis induced by TNF- related apoptosis-inducing Ligand (TRAIL).75 On the other hand, Lu et al. demonstrated that when PKCδ is phosphorylated on tyrosine 311 by c-Abl it mediated the apoptotic effect of H2O2 in glioma cells.76 In addition to the contribution to survival, Sarkar et al. demonstrated that in the presence of rottlerin, a relatively selective PKCδ inhibitor, the tenascin-dependent invasive ability of glioma cells was decreased, indicating that this PKC isoform also contributes to the invasion ability of glioma cells.39

Overexpression of PKCε was detected in histological samples from anaplastic astrocytoma, GBM and gliosarcoma and is considered an important marker of negative disease outcome.77 In GBM cell cultures, PKCε expression was found to be elevated between three to 30 times that of normal protein levels.77 The study of the PKCε contribution to gliomagenesis showed that the introduction of dominant-negative PKCε or the knockdown of PKCε sensitized glioma cells to apoptosis.25,54 , 78 In addition, it was also shown that PKCε may positively regulate integrin dependent adhesion and motility through the scaffolding protein receptor for activated C Kinase 1 (RACK1) of glioma cells.78-80 More recently, it was demonstrated that PKCε/vimentin may contribute to the trafficking of integrin-beta1 confirming that PKCε participates in cell to cell adhesion process.81

PKCη also contributes to increased GBM cells proliferation.59,82,83 Aeder et al. demonstrated that this proliferative stimulus was mediated by the activation of the downstream targets of PKCη AKT and mTOR.59 In addition, it was demonstrated that the activation of mTOR by PKCη was independent of AKT.59 More recently, Uht et al. showed that the increased proliferation induced by PKCη is also associated with the activation of MEK/MAP signaling pathways.83

The activation of PKCι in glioma may occur by aberrant upstream PI3K signaling.40 Once activated it seems that this PKC isoform may promote motility and invasion of GBM cells by coordinating lamellipodia and may stimulate cell cycle progression contributing to glioma cells escape from apoptosis and to the increased proliferation of these tumor cells.41 The contribution of PKCι to proliferation was also demonstrated in experiments where the silencing of PKCı induced a decrease in the proliferation of glioma cells.42,84

Regarding PKCζ is known that it can mediated a mitogenic phenotype in GBMs by activating the mTOR pathway in parallel to the PI3K/AKT pathway.59 In addition, it was also demonstrated that PKCζ is involved in the signaling cascade that controls the transcription of the MMP-9 gene via the NF-κB-dependent pathway in the C6 glioma cells.85,86 Since MMP-9 contributes to tumor invasion and to the disruption of the blood-brain barrier, it seems that PKCζ plays a very important role in gliomagenesis.

Taking altogether, these results showed that although PKCs have a clear role in development of glioma, the contribution of each isoform depends on phosphorylation of tyrosine residues, occurrence of oncogenic mutations, type of stimuli and cell environment. Therefore, in spite of the apparent value of PKC as a therapeutic target additional work is needed before PKC has a value-added tool in the clinical decision-making process.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cbt/article/23615

References

- 1.Gladson CL, Prayson RA, Liu WM. The pathobiology of glioma tumors. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:33–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weller M. Novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to malignant glioma. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13210. doi: 10.4414/smw.2011.13210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furnari FB, Fenton T, Bachoo RM, Mukasa A, Stommel JM, Stegh A, et al. Malignant astrocytic glioma: genetics, biology, and paths to treatment. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2683–710. doi: 10.1101/gad.1596707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stupp R, Hegi ME. Treatment of brain tumors. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2352–3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castro MG, Candolfi M, Kroeger K, King GD, Curtin JF, Yagiz K, et al. Gene therapy and targeted toxins for glioma. Curr Gene Ther. 2011;11:155–80. doi: 10.2174/156652311795684722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarkaria JN, Kitange GJ, James CD, Plummer R, Calvert H, Weller M, et al. Mechanisms of chemoresistance to alkylating agents in malignant glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2900–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shapiro WR. Current therapy for brain tumors: back to the future. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:429–32. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.4.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Gilbert MR, Chakravarti A. Chemoradiotherapy in malignant glioma: standard of care and future directions. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4127–36. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.8554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stupp R, van den Bent MJ, Cairncross JG, Hegi ME. Biological predictors for chemotherapy response. Ejc Supplements. 2005;3:25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, Hamou MF, de Tribolet N, Weller M, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:997–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel S, DiBiase S, Meisenberg B, Flannery T, Patel A, Dhople A, et al. Phase I clinical trial assessing temozolomide and tamoxifen with concomitant radiotherapy for treatment of high-grade glioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:739–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis KD, Gibbs P, O’Day S, Richards J, Weber J, Anderson C, et al. A phase II study of biochemotherapy for advanced melanoma incorporating temozolomide, decrescendo interleukin-2 and GM-CSF. Cancer Invest. 2005;23:303–8. doi: 10.1081/CNV-58832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mercer RW, Tyler MA, Ulasov IV, Lesniak MS. Targeted therapies for malignant glioma: progress and potential. BioDrugs. 2009;23:25–35. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200923010-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman HS, Kerby T, Calvert H. Temozolomide and treatment of malignant glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2585–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.do Carmo A, Patricio I, Cruz MT, Carvalheiro H, Oliveira CR, Lopes MC. CXCL12/CXCR4 promotes motility and proliferation of glioma cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9:56–65. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.1.10342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carmo A, Carvalheiro H, Crespo I, Nunes I, Lopes MC. Effect of temozolomide on the U-118 glioma cell line. Oncol Lett. 2011;2:1165–70. doi: 10.3892/ol.2011.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanzawa T, Germano IM, Komata T, Ito H, Kondo Y, Kondo S. Role of autophagy in temozolomide-induced cytotoxicity for malignant glioma cells. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:448–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan QW, Weiss WA. Targeting the RTK-PI3K-mTOR axis in malignant glioma: overcoming resistance. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010;347:279–96. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan QW, Cheng C, Knight ZA, Haas-Kogan D, Stokoe D, James CD, et al. EGFR signals to mTOR through PKC and independently of Akt in glioma. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Meir EG, Hadjipanayis CG, Norden AD, Shu HK, Wen PY, Olson JJ. Exciting new advances in neuro-oncology: the avenue to a cure for malignant glioma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:166–93. doi: 10.3322/caac.20069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arora A, Scholar EM. Role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:971–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.084145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baselga J. Targeting tyrosine kinases in cancer: the second wave. Science. 2006;312:1175–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1125951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griner EM, Caino MC, Sosa MS, Colón-González F, Chalmers MJ, Mischak H, et al. A novel cross-talk in diacylglycerol signaling: the Rac-GAP beta2-chimaerin is negatively regulated by protein kinase Cdelta-mediated phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16931–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.099036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basu A, Sivaprasad U. Protein kinase Cepsilon makes the life and death decision. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1633–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martiny-Baron G, Fabbro D. Classical PKC isoforms in cancer. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55:477–86. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.da Rocha AB, Mans DRA, Regner A, Schwartsmann G. Targeting protein kinase C: new therapeutic opportunities against high-grade malignant gliomas? Oncologist. 2002;7:17–33. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.7-1-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinberg SF. Structural basis of protein kinase C isoform function. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1341–78. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00034.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feldkamp MM, Lau N, Guha A. Signal transduction pathways and their relevance in human astrocytomas. J Neurooncol. 1997;35:223–48. doi: 10.1023/A:1005800114912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ali AS, Ali S, El-Rayes BF, Philip PA, Sarkar FH. Exploitation of protein kinase C: a useful target for cancer therapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki A, Akimoto K, Ohno S. Protein kinase C lambda/iota (PKClambda/iota): a PKC isotype essential for the development of multicellular organisms. J Biochem. 2003;133:9–16. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Besson A, Yong VW. Involvement of p21(Waf1/Cip1) in protein kinase C alpha-induced cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4580–90. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.13.4580-4590.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu J-G, Wang X-F, Zhou J-S, Wang F-C, Li X-W, Lü H-Z. Activation of PKC-α is required for migration of C6 glioma cells. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2010;70:239–45. doi: 10.55782/ane-2010-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oster H, Leitges M. Protein kinase C alpha but not PKCzeta suppresses intestinal tumor formation in ApcMin/+ mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6955–63. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fields AP, Calcagno SR, Krishna M, Rak S, Leitges M, Murray NR. Protein kinase Cbeta is an effective target for chemoprevention of colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1643–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cameron AJ, Procyk KJ, Leitges M, Parker PJ. PKC alpha protein but not kinase activity is critical for glioma cell proliferation and survival. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:769–79. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marengo B, De Ciucis C, Ricciarelli R, Passalacqua M, Nitti M, Zingg JM, et al. PKCδ sensitizes neuroblastoma cells to L-buthionine-sulfoximine and etoposide inducing reactive oxygen species overproduction and DNA damage. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steinberg SF. Distinctive activation mechanisms and functions for protein kinase Cdelta. Biochem J. 2004;384:449–59. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarkar S, Yong VW. Reduction of protein kinase C delta attenuates tenascin-C stimulated glioma invasion in three-dimensional matrix. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:311–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baldwin RM, Parolin DA, Lorimer IA. Regulation of glioblastoma cell invasion by PKC iota and RhoB. Oncogene. 2008;27:3587–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baldwin RM, Barrett GM, Parolin DA, Gillies JK, Paget JA, Lavictoire SJ, et al. Coordination of glioblastoma cell motility by PKCι. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:233–46. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baldwin RM, Garratt-Lalonde M, Parolin DA, Krzyzanowski PM, Andrade MA, Lorimer IA. Protection of glioblastoma cells from cisplatin cytotoxicity via protein kinase Ciota-mediated attenuation of p38 MAP kinase signaling. Oncogene. 2006;25:2909–19. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bononi A, Agnoletto C, De Marchi E, Marchi S, Patergnani S, Bonora M, et al. Protein kinases and phosphatases in the control of cell fate. Enzyme Res. 2011;2011:329098. doi: 10.4061/2011/329098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fox TE, Houck KL, O’Neill SM, Nagarajan M, Stover TC, Pomianowski PT, et al. Ceramide recruits and activates protein kinase C zeta (PKC zeta) within structured membrane microdomains. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12450–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700082200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Müller G, Ayoub M, Storz P, Rennecke J, Fabbro D, Pfizenmaier K. PKC zeta is a molecular switch in signal transduction of TNF-alpha, bifunctionally regulated by ceramide and arachidonic acid. EMBO J. 1995;14:1961–9. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Totoń E, Ignatowicz E, Skrzeczkowska K, Rybczyńska M. Protein kinase Cε as a cancer marker and target for anticancer therapy. Pharmacol Rep. 2011;63:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(11)70395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Griner EM, Kazanietz MG. Protein kinase C and other diacylglycerol effectors in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:281–94. doi: 10.1038/nrc2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frey MR, Saxon ML, Zhao X, Rollins A, Evans SS, Black JD. Protein kinase C isozyme-mediated cell cycle arrest involves induction of p21(waf1/cip1) and p27(kip1) and hypophosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein in intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9424–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Besson A, Yong VW. Involvement of p21(Waf1/Cip1) in protein kinase C alpha-induced cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4580–90. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.13.4580-4590.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mullin JM, Laughlin KV, Ginanni N, Marano CW, Clarke HM, Peralta Soler A. Increased tight junction permeability can result from protein kinase C activation/translocation and act as a tumor promotional event in epithelial cancers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;915:231–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lønne GK, Cornmark L, Zahirovic IO, Landberg G, Jirström K, Larsson C. PKCalpha expression is a marker for breast cancer aggressiveness. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:76–90. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McKiernan E, O’Brien K, Grebenchtchikov N, Geurts-Moespot A, Sieuwerts AM, Martens JW, et al. Protein kinase Cdelta expression in breast cancer as measured by real-time PCR, western blotting and ELISA. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1644–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nakagawa M, Oliva JL, Kothapalli D, Fournier A, Assoian RK, Kazanietz MG. Phorbol ester-induced G1 phase arrest selectively mediated by protein kinase Cdelta-dependent induction of p21. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33926–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505748200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gorin MA, Pan Q. Protein kinase C epsilon: an oncogene and emerging tumor biomarker. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:9–17. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pan Q, Bao LW, Kleer CG, Sabel MS, Griffith KA, Teknos TN, et al. Protein kinase C epsilon is a predictive biomarker of aggressive breast cancer and a validated target for RNA interference anticancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8366–71. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pan Q, Bao LW, Teknos TN, Merajver SD. Targeted disruption of protein kinase C epsilon reduces cell invasion and motility through inactivation of RhoA and RhoC GTPases in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9379–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mischak H, Goodnight JA, Kolch W, Martiny-Baron G, Schaechtle C, Kazanietz MG, et al. Overexpression of protein kinase C-delta and -epsilon in NIH 3T3 cells induces opposite effects on growth, morphology, anchorage dependence, and tumorigenicity. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6090–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fima E, Shtutman M, Libros P, Missel A, Shahaf G, Kahana G, et al. PKCeta enhances cell cycle progression, the expression of G1 cyclins and p21 in MCF-7 cells. Oncogene. 2001;20:6794–804. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aeder SE, Martin PM, Soh JW, Hussaini IM. PKC-eta mediates glioblastoma cell proliferation through the Akt and mTOR signaling pathways. Oncogene. 2004;23:9062–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kashiwagi M, Ohba M, Watanabe H, Ishino K, Kasahara K, Sanai Y, et al. PKCeta associates with cyclin E/cdk2/p21 complex, phosphorylates p21 and inhibits cdk2 kinase in keratinocytes. Oncogene. 2000;19:6334–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nazarenko I, Jenny M, Keil J, Gieseler C, Weisshaupt K, Sehouli J, et al. Atypical protein kinase C zeta exhibits a proapoptotic function in ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:919–34. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Donson AM, Banerjee A, Gamboni-Robertson F, Fleitz JM, Foreman NK. Protein kinase C zeta isoform is critical for proliferation in human glioblastoma cell lines. J Neurooncol. 2000;47:109–15. doi: 10.1023/A:1006406208376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Regala RP, Weems C, Jamieson L, Khoor A, Edell ES, Lohse CM, et al. Atypical protein kinase C iota is an oncogene in human non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8905–11. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fields AP, Frederick LA, Regala RP. Targeting the oncogenic protein kinase Ciota signalling pathway for the treatment of cancer. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:996–1000. doi: 10.1042/BST0350996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kikuchi K, Soundararajan A, Zarzabal LA, Weems CR, Nelon LD, Hampton ST, et al. Protein kinase C iota as a therapeutic target in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Oncogene. 2012;46:1–12. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koivunen J, Aaltonen V, Peltonen J. Protein kinase C (PKC) family in cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 2006;235:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nakada M, Hayashi Y, Hamada J. Role of Eph/ephrin tyrosine kinase in malignant glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13:1163–70. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Neyns B, Chaskis C, Dujardin M, Everaert H, Sadones J, Nupponen NN, et al. Phase II trial of sunitinib malate in patients with temozolomide refractory recurrent high-grade glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2038. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cohen EE, Zhu H, Lingen MW, Martin LE, Kuo WL, Choi EA, et al. A feed-forward loop involving protein kinase Calpha and microRNAs regulates tumor cell cycle. Cancer Res. 2009;69:65–74. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Leirdal M, Sioud M. Protein kinase Calpha isoform regulates the activation of the MAP kinase ERK1/2 in human glioma cells: involvement in cell survival and gene expression. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun. 2000;4:106–10. doi: 10.1006/mcbr.2000.0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mut M, Amos S, Hussaini IM. PKC alpha phosphorylates cytosolic NF-kappaB/p65 and PKC delta delays nuclear translocation of NF-kappaB/p65 in U1242 glioblastoma cells. Turk Neurosurg. 2010;20:277–85. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.3008-10.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kohutek ZA, diPierro CG, Redpath GT, Hussaini IM. ADAM-10-mediated N-cadherin cleavage is protein kinase C-alpha dependent and promotes glioblastoma cell migration. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4605–15. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5126-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Graff JR, McNulty AM, Hanna KR, Konicek BW, Lynch RL, Bailey SN, et al. The protein kinase Cbeta-selective inhibitor, Enzastaurin (LY317615.HCl), suppresses signaling through the AKT pathway, induces apoptosis, and suppresses growth of human colon cancer and glioblastoma xenografts. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7462–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wick W, Puduvalli VK, Chamberlain MC, van den Bent MJ, Carpentier AF, Cher LM, et al. Phase III study of enzastaurin compared with lomustine in the treatment of recurrent intracranial glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1168–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Okhrimenko H, Lu W, Xiang C, Hamburger N, Kazimirsky G, Brodie C. Protein kinase C-epsilon regulates the apoptosis and survival of glioma cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7301–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lu W, Finnis S, Xiang C, Lee HK, Markowitz Y, Okhrimenko H, et al. Tyrosine 311 is phosphorylated by c-Abl and promotes the apoptotic effect of PKCdelta in glioma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;352:431–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sharif TR, Sharif M. Overexpression of protein kinase C epsilon in astroglial brain tumor derived cell lines and primary tumor samples. Int J Oncol. 1999;15:237–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shinohara H, Kayagaki N, Yagita H, Oyaizu N, Ohba M, Kuroki T, et al. A protective role of PKCepsilon against TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis in glioma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284:1162–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Besson A, Davy A, Robbins SM, Yong VW. Differential activation of ERKs to focal adhesions by PKC epsilon is required for PMA-induced adhesion and migration of human glioma cells. Oncogene. 2001;20:7398–407. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Besson A, Wilson TL, Yong VW. The anchoring protein RACK1 links protein kinase Cepsilon to integrin beta chains. Requirements for adhesion and motility. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:22073–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111644200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fortin S, Le Mercier M, Camby I, Spiegl-Kreinecker S, Berger W, Lefranc F, et al. Galectin-1 is implicated in the protein kinase C epsilon/vimentin-controlled trafficking of integrin-beta1 in glioblastoma cells. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:39–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Martin PM, Hussaini IM. PKC eta as a therapeutic target in glioblastoma multiforme. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2005;9:299–313. doi: 10.1517/14728222.9.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Uht RM, Amos S, Martin PM, Riggan AE, Hussaini IM. The protein kinase C-eta isoform induces proliferation in glioblastoma cell lines through an ERK/Elk-1 pathway. Oncogene. 2007;26:2885–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Patel R, Win H, Desai S, Patel K, Matthews JA, Acevedo-Duncan M. Involvement of PKC-iota in glioma proliferation. Cell Prolif. 2008;41:122–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2007.00506.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Estève PO, Chicoine E, Robledo O, Aoudjit F, Descoteaux A, Potworowski EF, et al. Protein kinase C-zeta regulates transcription of the matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene induced by IL-1 and TNF-alpha in glioma cells via NF-kappa B. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35150–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108600200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Guo H, Gu F, Li W, Zhang B, Niu R, Fu L, et al. Reduction of protein kinase C zeta inhibits migration and invasion of human glioblastoma cells. J Neurochem. 2009;109:203–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]