Abstract

FAS-associated death domain (FADD) is a key adaptor protein that bridges a death receptor (e.g., death receptor 5; DR5) to caspase-8 to form the death-inducing signaling complex during apoptosis. The expression and prognostic impact of FADD in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) have not been well studied. This study focuses on detecting FADD expression and analyzing its prognostic impact in primary and metastatic HNSCCs. We found a significant increase in FADD expression in primary tumors with lymph node metastasis (LNM) in comparison with primary tumors with no LNM. This increase was significantly less in the matched LNM tissues. Both univariate and multivariable analyses indicated that lower FADD expression was significantly associated with better disease-free survival and overall survival in HNSCC patients with LNM although FADD expression did not significantly affect survival of HNSCC patients without LNM . When combined with DR5 or caspase-8 expression, patients with LNM expressing both low FADD and DR5 or both low FADD and caspase-8 had significantly better prognosis than those expressing both high FADD and DR5 or both high FADD and caspase-8. However, the expression of both low FADD and caspase-8 was significantly linked to worse overall survival compared with both high FADD and caspase-8 expression in HNSCC patients without LNM. Hence, we suggest that FADD alone or together with DR5 and caspase-8 participates in metastatic process of HNSCC.

Keywords: FADD, caspase-8, death receptor 5, head and neck cancer, immunohistochemistry

Introduction

Lymph node metastasis (LNM) occurs commonly in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and substantially impacts patient survival. The 5-y survival rate for patients with LNM is approximately 25−50%.1 Thus, better understanding of the biology of HNSCC metastasis and the development of better treatments for metastatic HNSCC are urgently needed.

Fas-associated death domain (FADD) is a critical apoptotic adaptor molecule that interacts with cell surface death receptors (e.g., death receptor 5; DR5), recruits caspase-8 and ultimately mediates cell apoptotic signals. Through its C-terminal death domain, this protein can be recruited by a death receptor and then participates in the death signaling initiated by the death receptor through further recruiting caspase-8 via its unmasked N-terminal death effector domain. In addition to forming the death-inducing signaling complex during apoptosis, FADD, under certain circumstances, is also involved in recruitment of other proteins such as RIP1 and TRAF2 to form secondary signaling complexes, resulting in activation of certain signaling pathways such as c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) or NFκB.2,3

Besides being an essential component in mediating death receptor-mediated apoptosis, FADD has been shown to be required for T-cell proliferation and cell cycle progression.4 Increased FADD expression has been detected in human lung cancer and is associated with poor survival.5 cDNA microarray analysis or quantitative reverse transcription PCR has revealed that FADD expression is elevated in certain types of HNSCC (e.g., laryngeal).6,7 This elevation is likely due to increased DNA amplification.7,8 Moreover, positive FADD expression is significantly associated with LNM of oral (e.g., tongue) squamous cell carcinoma and worse survival.7,8

Our previous study has shown that the expression levels of both DR5 and particularly caspase-8, two other key molecules involved in the death receptor-mediated apoptotic signaling pathway, impact prognosis of HNSCC patients with opposing outcomes depending on the presence of LNM. Higher expression levels of DR5, caspase-8 or both are significantly associated with poorer prognosis of HNSCC patients with LNM in comparison with those expressing lower levels of these proteins. In contrast, elevated expression of caspase-8 is a positive prognostic marker for HNSCC patients with no evidence of LNM.9 These findings suggest that the death receptor signaling pathway or its components are involved in regulation of metastasis of HNSCC.

In this study, we were particularly interested in detecting FADD expression in HNSCC with and without LNM and determining its prognostic impact. Thus, we performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) to detect FADD expression in three groups of tumor samples: primary tumors from patients with no evidence of LNM (Tu-met), primary tumors from patients with LNM (Tu+met) and the matching LNM.

Results

Detection of FADD expression in HNSCC tissues

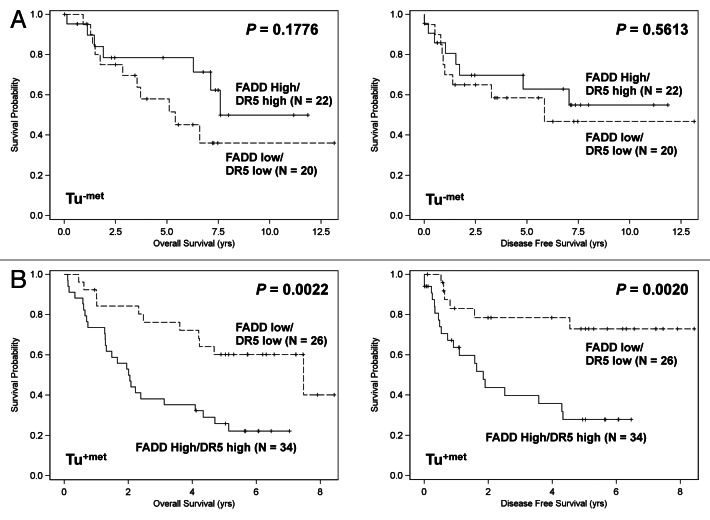

We conducted IHC to detect FADD expression on 100 samples in each group. A total of 100 samples in Tu-met, 97 samples in Tu+met and 93 samples in the LNM group had evaluable tumor tissues. The positive staining rates for FADD (≥ 10% positive cancer cell staining) in the Tu-met, Tu+met and LNM groups were 88% (88/100), 86.6% (84/97) and 82.7% (76/93), respectively. Figure 1A shows representative staining of FADD in different groups. Cytoplasmic staining of FADD was primarily detected in tumor cells. When using weight index (WI), which reflects both % positive stain in tumor and stain intensity, as a parameter, FADD expression was found to be significantly elevated in the Tu+met group when compared with that in the Tu-met group (p < 0.001). However, there was not a significant increase in FADD expression in the LNM group when compared with Tu-met group. When comparing FADD expression between Tu+met and LNM groups, FADD expression was significantly higher in the Tu+met group than in the LNM group (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Representative IHC staining of FADD (A) and comparison of FADD expression (B) among different groups of HNSCC. The pictures were taken with a magnification of 200×.

Univariate analysis indicated that there was not a significant association between FADD expression and histological grade (or differentiation), gender, smoking status, age at diagnosis or tumor size in both Tu-met and Tu+met groups. However, both univariate and multivariable analyses showed that Tu+met patients with high FADD levels in their primary sites tended to have oral cavity tumors, while those with low FADD levels in their primary sites tended to have oropharyngeal or laryngeal tumors for same gender and tumor stage.

Prognostic impact of FADD expression

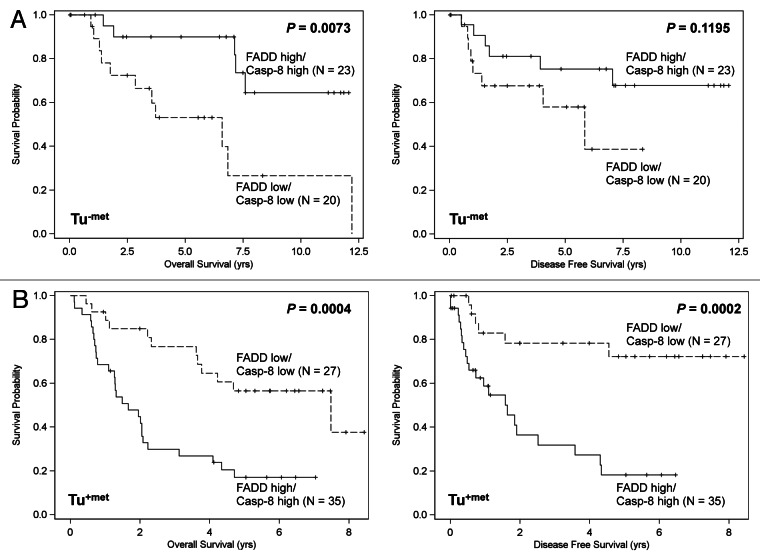

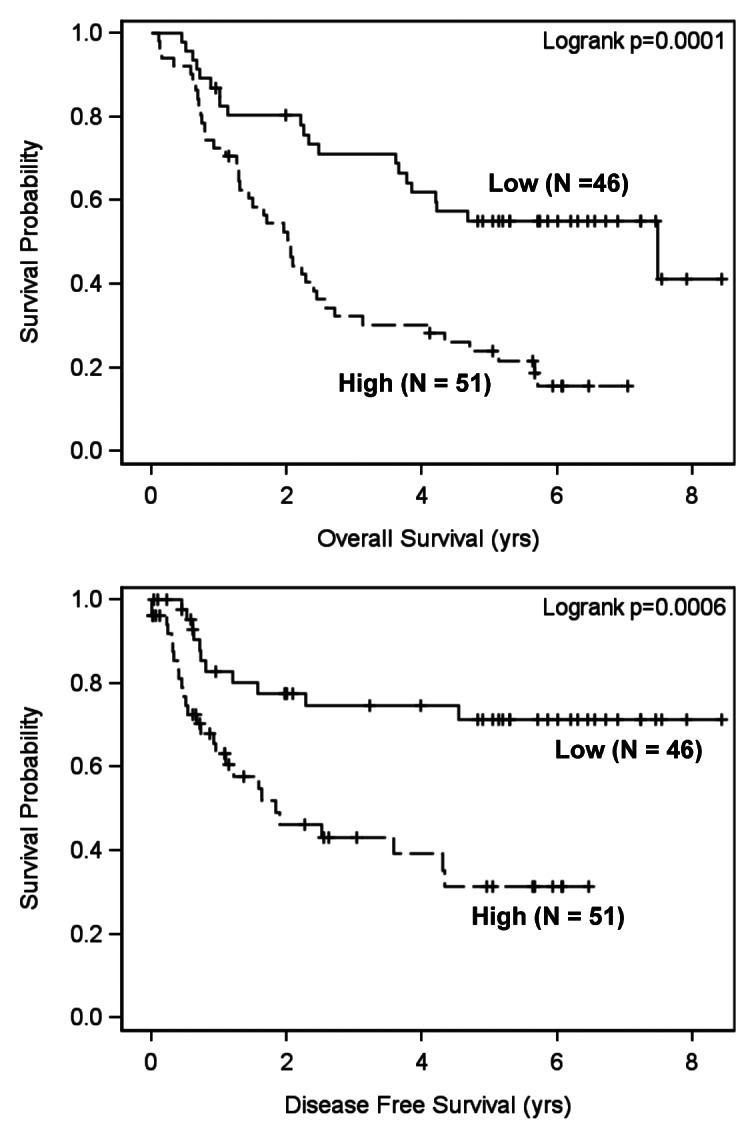

We then determined whether FADD expression impacts prognosis. Univariate analysis showed that there was not a significant association between FADD levels and patient survival in the Tu-met group, suggesting that FADD expression does not impact the survival of patients without LNM. However, in Tu+met patients, FADD levels significantly impact both disease-free survival and overall survival (p < 0.01; HR = 1.004). After adjusting for covariates (age, gender, site and treatment) in the multivariable analysis, FADD levels in Tu+met patients maintained a significant association with both disease-free survival and overall survival (p < 0.05; HR = 1.003 or 1.004). The Log-rank test with dichotomized FADD level showed identical effects on disease-free survival and overall survival (Fig. 2). Specifically, patients having LNM with lower FADD expression tended to survive better than those with higher FADD expression.

Figure 2. Impact of FADD expression on disease-free survival and overall survival in HNSCC patients with LNM (Tu+met). Kaplan-Meier plots were generated according to high (greater than the mean value) and low (less than or equal to the mean value) levels of FADD.

Prognostic impact of FADD plus DR5 or caspase-8

In the same cohort of HNSCC specimens, the expression of DR5 and caspase-8, another two key proteins in the process of death receptor-regulated apoptosis, has been previously shown by us to significantly impact the survival of HNSCC patients depending on the presence of LNM.9 Here we conducted analyses to look at the impact of FADD in combination with DR5 or caspase-8 expression on the survival of HNSCC patients. The log-rank test in the univariate analyses showed that the impact of combined FADD and DR5 expression on patient survival showed no difference from of FADD (Fig. 2) or DR5 alone.9 Specifically, the levels of FADD combined with DR5 did not significantly affect patient survival in HNSCC with no LNM (Tu-met) (Fig. 3A). However, patients with both higher FADD and DR5 expression had poorer overall survival and disease-free survival than patients with both low FADD and caspase-8 levels in HNSCC with LNM (Tu+met) (p = 0.0022 and p = 0.002, respectively) (Fig. 3B). The multivariable Cox proportional hazard model analyses generated similar results (p < 0.05).

Figure 3. Impact of FADD and DR5 combination on disease-free survival and overall survival in HNSCC patients without LNM (Tu-met) (A) and with LNM (Tu+met) (B). Kaplan-Meier plots were generated according to high (greater than the mean value) and low (less than or equal to the mean value) levels of FADD and DR5.

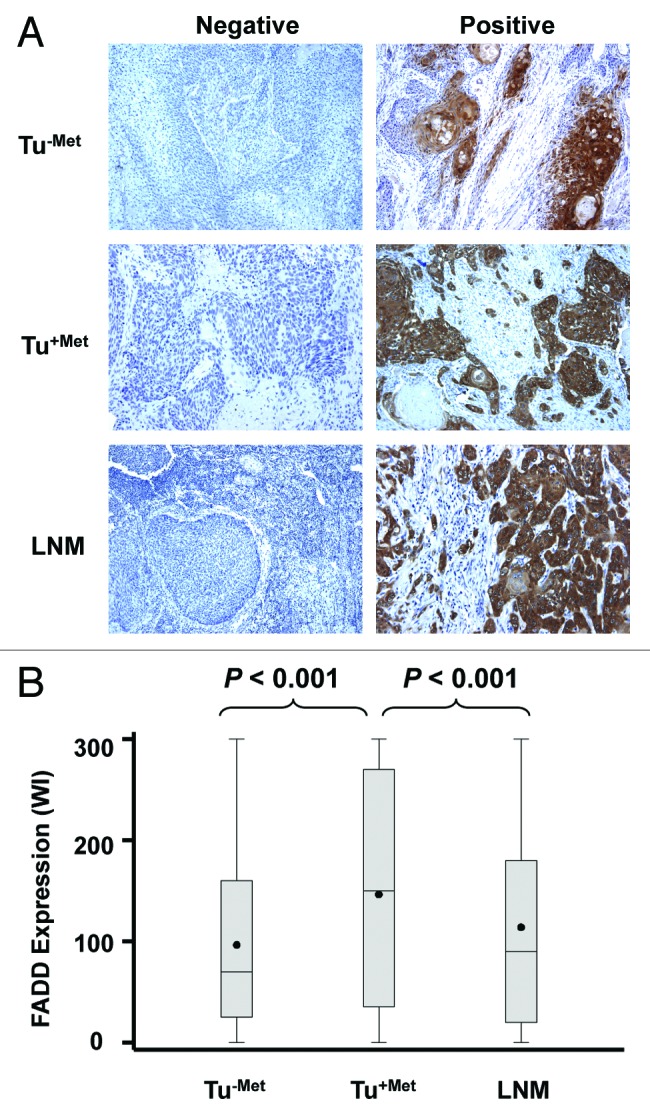

Both univariate and multivariable analyses showed that the expression levels of FADD combined with caspase-8 significantly affected the survival of HNSCC patients with opposing outcomes depending on the presence of LNM. The log-rank test showed that patients with high expression of both FADD and caspase-8 had significantly better overall survival than those with low expression of both FADD and caspase-8 (p = 0.0073) in HNSCC with no LNM (Tu-met) (Fig. 4A). In contrast, patients expressing high levels of both FADD and caspase-8 had significantly poorer overall survival (p = 0.0004) and disease-free survival (p = 0.0002) compared with those expressing low levels of both FADD and caspase-8 in HNSCC with LNM (Tu+met) (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Impact of FADD and caspase-8 combination on disease-free survival and overall survival in HNSCC patients without LNM (Tu-met) (A) and with LNM (Tu+met) (B).Kaplan-Meier plots were generated according to high (greater than the mean value) and low (less than or equal to the mean value) levels of FADD and caspase-8.

Discussion

Elevated FADD has been reported in oral and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma in comparison with the matched adjacent normal tissues and is associated with worse survival.6-8 Our HNSCC specimens were obtained from 100 cases of HNSSC with no LNM and 100 cases of HNSCC with LNM (including tissues from both primary tumors and matched lymph nodes), consisting of cancers in the oral cavity, oropharynx and larynx.9 We were interested in comparing FADD expression between HNSCC without and with LNM. As a result, the expression of FADD was found to be significantly elevated in HNSCC from the primary site of HNSCC with LNM (Tu+met) relative to that in HNSCC without LNM (Tu-met) (Fig. 1B). This finding suggests that FADD may be involved in positive regulation of LNM, hence warranting further study in this direction.

Increased number of studies have suggested that death receptor/caspase-8-mediated signaling plays either a suppressive or a promoting role in regulation of cancer metastasis depending on the experimental models, cells or tissue types used.10 In this study, we revealed that higher FADD expression was significantly associated with poor prognosis of HNSCC patients with LNM even though it had limited impact on the survival of HNSCC patients with no LNM (Fig. 2). We also generated similar results when FADD expression was combined with DR5 or with caspase-8 expression (Figs. 3 and 4). These findings are consistent with our previous identification of the prognostic impact of DR5, caspase-8 or their combination in the same cohort of HNSCC specimens.9 Collectively, DR5/FADD/caspase-8 signaling appears to participate in positive regulation of LNM of HNSCC, thus warranting further investigation in this regard and in understanding the underlying mechanisms.

Based on our current and previous studies,9 the expression of DR5, FADD or their combination does not significantly impact the prognosis of HNSCC patients who have no evidence of LNM; however, elevated levels of caspase-8 alone, or combined with high levels of FADD or DR5, positively impacts the survival of this group of patients (i.e., Tu-met). This suggests that DR5/FADD/caspase-8 signaling may have a suppressive function in regulation of cancer metastasis. Collectively, we suggest that the involvement or function of DR5/FADD/caspase-8 signaling in regulation of cancer metastasis is dependent on the stage of cancer. One possibility is that DR5/FADD/caspase-8 signaling suppresses metastasis through functioning as an apoptotic signaling mediator in the early stage of cancer, in which apoptotic resistance has not been fully established. However, in the late stage where cancer cells have become resistant to apoptosis, the activation of DR5/FADD/caspase-8 signaling may enhance metastasis through a non-apoptotic function, which has yet to be uncovered. Thus, it will be crucial to fully understand the biology behind this interesting phenomenon so that we can develop strategies to target this signaling pathway for the treatment of metastatic HNSCC.

Materials and Methods

Tissue specimens

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Emory University. The tissue collection and the clinicopathologic parameters including age, gender, smoking history, tumor location and histologic grade were described in our previous study.9 Briefly, three groups of tissues were used in this study: Tu+met, with the paired LNM, and Tu-met. Each group has 100 samples. All tissues were from treatment-naïve patients, and in the non-metastatic group, no metastases were noted for at least two years post-surgery.

IHC and staining score

FADD was stained with IHC as described previously.9 FADD antibody (clone H181; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) was used at a dilution of 1:500. Both the percentage of positive staining in tumor cells and the intensity of staining were scored. The intensity of IHC staining was measured using a numerical scale (0 = no expression, 1 = weak expression, 2 = moderate expression, 3 = strong expression). The staining data were quantified as a WI (% positive stain in tumor × intensity score) as previously described.9,11,12 The WI was determined by 2 individuals, and the final values were the average of the two readings.

Statistical analyses

Median differences in FADD WIs among different groups were assessed with Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon rank test. Correlations between FADD WIs and clinical characteristics were performed in all patients and within each group after adjusting for patients’ metastatic status. A logistic regression model was applied to assess the association between WIs and binary variables (gender and smoking status). Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed for categorical variables with more than two categories (tumor site, tumor size, node status and differentiation status). The Cox proportional hazards model was used for univariate and multivariable survival analysis for continuous FADD. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed using Schoenfeld residuals. FADD was also dichotomized as low and high based on the observed mean value. The log-rank test was used to test whether Kaplan-Meier survival estimators with different FADD levels were statistically different. Multivariable analyses were performed with those clinical variables shown to be statistically significant in the univariate analyses. All data processing and statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9 (SAS Institute).

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Anthea Hammond in our department for editing the manuscript. G.Z.C., D.M.S., F.R.K. and S.Y.S. are Georgia Cancer Coalition Distinguished Cancer Scholars.

This study was supported by the Georgia Cancer Coalition Distinguished Cancer Scholar award (to S.Y.S.) and National Cancer Institute SPORE P50 grant CA128613 (project 2 to S.Y.S. and F.R.K.).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cbt/article/23636

References

- 1.Seiwert TY, Cohen EE. State-of-the-art management of locally advanced head and neck cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1341–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang A, Wilson NS, Ashkenazi A. Proapoptotic DR4 and DR5 signaling in cancer cells: toward clinical translation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:837–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalvez F, Ashkenazi A. New insights into apoptosis signaling by Apo2L/TRAIL. Oncogene. 2010;29:4752–65. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tourneur L, Chiocchia G. FADD: a regulator of life and death. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:260–9. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen G, Bhojani MS, Heaford AC, Chang DC, Laxman B, Thomas DG, et al. Phosphorylated FADD induces NF-kappaB, perturbs cell cycle, and is associated with poor outcome in lung adenocarcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12507–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500397102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomioka H, Morita K, Hasegawa S, Omura K. Gene expression analysis by cDNA microarray in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2006;35:206–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibcus JH, Menkema L, Mastik MF, Hermsen MA, de Bock GH, van Velthuysen ML, et al. Amplicon mapping and expression profiling identify the Fas-associated death domain gene as a new driver in the 11q13.3 amplicon in laryngeal/pharyngeal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6257–66. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prapinjumrune C, Morita K, Kuribayashi Y, Hanabata Y, Shi Q, Nakajima Y, et al. DNA amplification and expression of FADD in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39:525–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elrod HA, Fan S, Muller S, Chen GZ, Pan L, Tighiouart M, et al. Analysis of death receptor 5 and caspase-8 expression in primary and metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and their prognostic impact. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun SY. Understanding the Role of the Death Receptor 5/FADD/caspase-8 Death Signaling in Cancer Metastasis. Mol Cell Pharmacol. 2011;3:31–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Hunt JL, Landsittel DP, Muller S, Adler-Storthz K, Ferris RL, et al. Correlation of protease-activated receptor-1 with differentiation markers in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and its implication in lymph node metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8451–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller S, Su L, Tighiouart M, Saba N, Zhang H, Shin DM, et al. Distinctive E-cadherin and epidermal growth factor receptor expression in metastatic and nonmetastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: predictive and prognostic correlation. Cancer. 2008;113:97–107. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]