MULTI-FLORET SPIKELET1 determines spikelet meristem fate and sterile lemma identity in rice.

Abstract

The spikelet is a unique inflorescence structure of grass. The molecular mechanism that controls the development of the spikelet remains unclear. In this study, we identified a rice (Oryza sativa) spikelet mutant, multi-floret spikelet1 (mfs1), that showed delayed transformation of spikelet meristems to floral meristems, which resulted in an extra hull-like organ and an elongated rachilla. In addition, the sterile lemma was homeotically converted to the rudimentary glume and the body of the palea was degenerated in mfs1. These results suggest that the MULTI-FLORET SPIKELET1 (MFS1) gene plays an important role in the regulation of spikelet meristem determinacy and floral organ identity. MFS1 belongs to an unknown function clade in the APETALA2/ethylene-responsive factor (AP2/ERF) family. The MFS1-green fluorescent protein fusion protein is localized in the nucleus. MFS1 messenger RNA is expressed in various tissues, especially in the spikelet and floral meristems. Furthermore, our findings suggest that MFS1 positively regulates the expression of LONG STERILE LEMMA and the INDETERMINATE SPIKELET1 (IDS1)-like genes SUPERNUMERARY BRACT and OsIDS1.

In the reproductive phase of angiosperms, the shoot meristem is transformed into an inflorescence meristem, which then produces a floral meristem from which floral organs begin to develop, according to the mechanism known as the ABCDE model (Coen and Meyerowitz, 1991; Coen and Nugent, 1994; Dreni et al., 2007; Ohmori et al., 2009). An inflorescence can be classified as determinate or indeterminate based on whether its apical meristem is transformed into a terminal floral meristem. In an indeterminate inflorescence, the lateral meristem is permanently differentiated from the apical meristem, which is not converted into the terminal floral meristem, as occurs during the development of the inflorescences of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus). In contrast, in a determinate inflorescence, the apical meristem is transformed into the terminal floral meristem after the production of a fixed number of lateral meristems, as occurs during the development of the inflorescences of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum; Bradley et al., 1997; Ratcliffe et al., 1999; Sussex and Kerk, 2001; Chuck et al., 2008).

In general, inflorescences in grasses consist of branches and spikelets (Coen and Nugent, 1994; Itoh et al., 2005; Kobayashi et al., 2010). In these organisms, the branch meristem is determinate. It produces several lateral spikelet meristems, followed by the final production of a terminal spikelet meristem. The spikelet, the specific unit of the grass inflorescence, comprises a pair of bracts and one to 40 florets; it shows determinacy or indeterminacy depending on the species (Clifford, 1987; Malcomber et al., 2006). In species with a determinate spikelet, such as rice (Oryza sativa), after the production of fixed lateral floral meristems, the spikelet meristems are converted into terminal floral meristems, resulting in termination of the spikelet meristem fate. In contrast, in species with an indeterminate spikelet, such as wheat (Triticum aestivum), the spikelet meristem fate is maintained continuously and produces a variable number of lateral floral meristems.

In Arabidopsis, the gene TERMINAL FLOWER1 (TFL1) was shown to maintain indeterminacy in the fate of the inflorescence. In the tfl1 mutant, the inflorescence meristems were converted into floral meristems earlier than in the wild type, but the ectopic expression of TFL1 resulted in the transformation of floral meristems at a later stage of development to secondary inflorescence meristems (Bradley et al., 1997; Ratcliffe et al., 1999; Mimida et al., 2001). In rice, overexpression of either of the TFL1-like genes, RICE CENTRORADIALIS1 (RCN1) or RCN2, delayed the transition of branch meristems to spikelet meristems and finally resulted in the production of a greater number of branches and spikelets than in the wild type (Nakagawa et al., 2002; Rao et al., 2008).

To date, no gene that acts to maintain the indeterminacy of the spikelet meristem has been reported. However, two classes of genes have been shown to be involved in termination of the indeterminacy of spikelet meristems. One of these is the group of terminal floral meristem identity genes. A grass-specific LEAFY HULL STERILE1 (LHS1) clade in the SEPALLATA (SEP) subfamily belongs to this class. LHS1-like genes were found to be expressed only in the terminal floral meristem in species with spikelet determinacy, which suggested that they exclusively determine the production of the terminal floral meristem, by which the spikelet meristem acquires determinacy (Cacharroón et al., 1999; Malcomber and Kellogg, 2004; Zahn et al., 2005). The other class comprises the INDETERMINATE SPIKELET1 (IDS1)-like genes, which belong to the APETALA2/ethylene-responsive factor (AP2/ERF) family. Unlike LHS1-like genes, this class of genes regulates the correct timing of the transition of the spikelet meristem to the floral meristem but does not specify the identity of the terminal floral meristem. In maize (Zea mays), loss of IDS1 function produces extra florets (Chuck et al., 1998). In addition, mutation of SISTER OF IDS1 (SID1), a paralog of IDS1 in maize, resulted in no defects in terms of spikelet development. However, the ids1+sid1 double mutant failed to generate floral organs and instead developed more bract-like structures than are found in wild-type plants (Chuck et al., 2008). The rice genome contains two IDS1-like genes, SUPERNUMERARY BRACT (SNB) and OsIDS1. Loss of activity of SNB or OsIDS1 produced extra rudimentary glumes, and snb+osids1 double mutant plants developed more rudimentary glumes than either of its parental mutants (Lee et al., 2007; Lee and An, 2012). These results revealed that the mutated IDS1-like genes prolonged the activity of the spikelet meristem.

In most members of Oryzeae, the spikelet is distinct from those of other grasses, in that it comprises a pair of rudimentary glumes, a pair of sterile lemmas (empty glumes), and one floret (Schmidt and Ambrose, 1998; Ambrose et al., 2000; Kellogg, 2009; Hong et al., 2010). The rudimentary glumes are generally regarded as severely reduced bract organs, but the origin of sterile lemmas has been widely debated. Recent studies suggested that the sterile lemmas are the vestigial lemmas of two lateral florets. The gene LONG STERILE LEMMA (G1)/ELONGATED EMPTY GLUME1 (ELE1) is a member of a plant-specific gene family. In the g1/ele1 mutant, sterile lemmas were found to be homeotically transformed into lemmas (Yoshida et al., 2009; Hong et al., 2010). The OsMADS34 and EXTRA GLUME1 (EG1) genes were also shown to determine the identities of sterile lemmas. In the osmads34 and eg1 mutants, the sterile lemmas were enlarged and acquired the identities of lemmas (Li et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2010; Kobayashi et al., 2010). Additionally, the SEP-like gene LHS1/OsMADS1, which specifies the identities of both the lemma and the palea, was not expressed in sterile lemmas, and ectopic expression in sterile lemmas resulted in the transformation of sterile lemmas to lemmas (Jeon et al., 2000; Li et al., 2009; Tanaka et al., 2012). These findings suggest that the sterile lemma may be homologous to the lemma. Nevertheless, some researchers still considered that the sterile lemmas are instead vestigial bract-like structures similar to the rudimentary glumes (Schmidt and Ambrose, 1998; Kellogg, 2009; Hong et al., 2010).

In this study, we isolated the rice MULTI-FLORET SPIKELET1 (MFS1) gene, which belongs to a clade of unknown function in the AP2/ERF gene family. The mutation of MFS1 was shown to delay the transformation of the spikelet meristem to the floral meristem and to result in degeneration of the sterile lemma and palea. These results suggest that MFS1 plays an important role in the regulation of spikelet determinacy and organ identity. Our findings also reveal that MFS1 positively regulates the expression of G1 and the IDS1-like genes SNB and OsIDS1.

RESULTS

We identified two recessive mutants related to the development of the rice spikelet, mfs1-1 and mfs1-2 (Fig. 1; Supplemental Fig. S1). An allelism test revealed that the two mutants were allelic. Given that mfs1-1 showed more severe defects than mfs1-2, the rest of this paper focuses primarily on the mfs1-1 mutant.

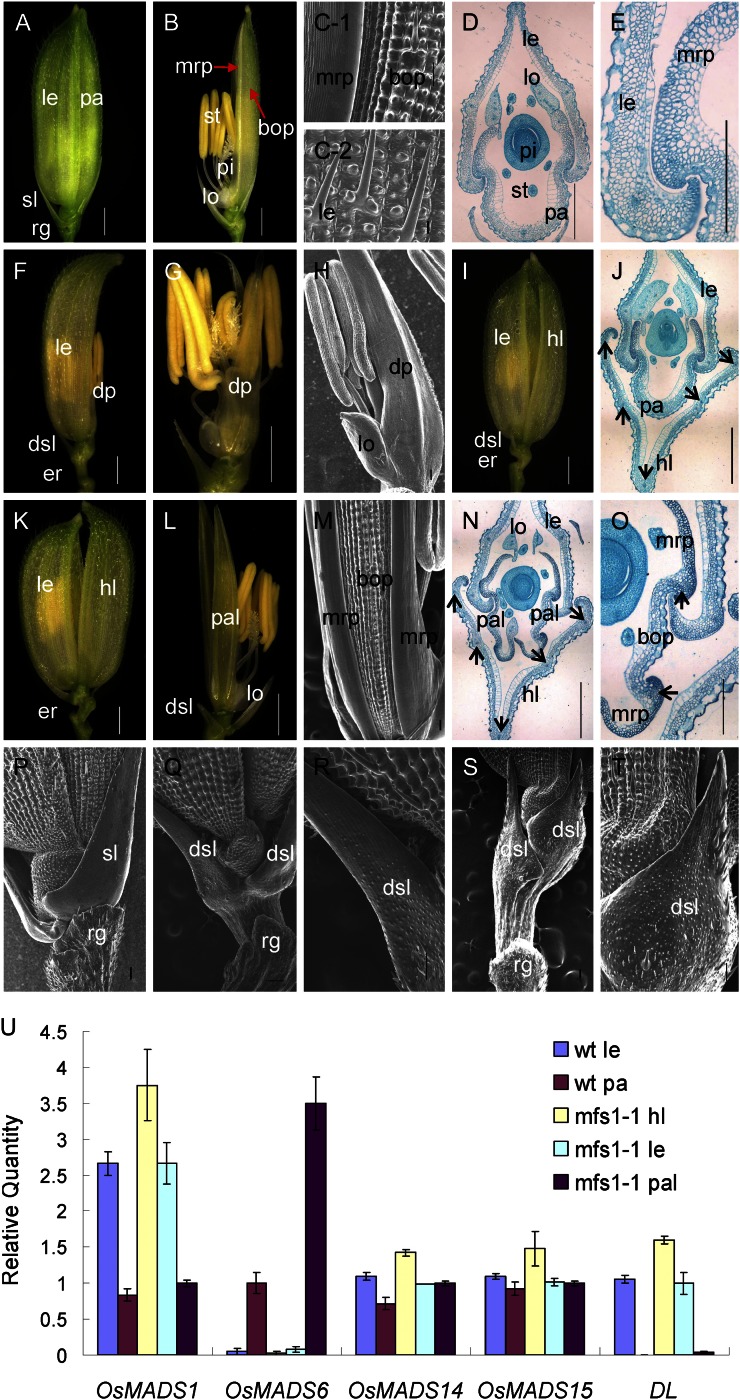

Figure 1.

Phenotypes of spikelets in the wild-type and mfs1-1. A and B, Wild-type spikelet. C-1, Epidermal surface of wild-type palea. C-2, Epidermal surface of wild-type lemma. D and E, Histological analysis of wild-type spikelet. F and G, mfs1-1 spikelet with a degenerated palea. H, Epidermal surface of the degenerated palea in G. I, mfs1-1 spikelet with an extra hull and a normal palea. J, Histological analysis of mfs1-1 spikelet with an extra hull and a normal palea. K and L, mfs1-1 spikelet with an extra hull and degenerated paleae. M, Epidermal surface of the degenerated palea in L. N and O, Histological analysis of an mfs1-1 spikelet with an extra hull and degenerated paleae. P, Epidermal surface of the sterile lemma and rudimentary glume in the wild type. Q to T, Epidermal surface of the degenerated sterile lemma and rudimentary glume in mfs1-1. U, Relative expression levels of floral organ identity genes in wild-type (wt) and mfs1-1 floral organs. dp, Degenerated palea; dsl, degenerated sterile lemma; er, elongated rachilla; hl, hull (lemma/palea)-like organ; le, lemma; lo, lodicule; pa, palea; pal, palea-like organ; pi, pistil; rg, rudimentary glume; sl, sterile lemma; st, stamen. Black arrows represent vascular bundles. Bars = 1,000 μm in A, B, F, G, I, K, and L and 100 μm in C to E, H, J, M, and N to T. Error bars in U indicate sd.

mfs1-1 Shows Pleiotropic Defects in Spikelet Development

Generally, a wild-type rice spikelet consists of one pair of rudimentary glumes, one pair of sterile lemmas, and one terminal fertile floret. The floret comprises four whorls of floral organs: one lemma and one palea in whorl 1, two lodicules in whorl 2, six stamens in whorl 3, and one pistil with two stigmas in whorl 4 (Fig. 1, A and B).

In wild-type spikelets, the sterile lemma was shown to be larger than the rudimentary glume (Fig. 1A). Most of the epidermis of the sterile lemma was smooth and consisted of regularly arranged flat cells and rare cells with trichomes on the abaxial side (Fig. 1P). The epidermal cells of rudimentary glumes were arranged irregularly and bore lots of protrusions and trichomes (Fig. 1P). In contrast, the sterile lemma was found to be reduced to various degrees, even resembling the rudimentary glume in size in the mfs1-1 mutant (Fig. 1, F, I, and L; Supplemental Fig. S1). The abundant protrusions and trichomes were borne on the middle and lower epidermis of degenerated sterile lemmas, which were highly similar to those of the rudimentary glume (Fig. 1, Q–T). Meanwhile, the regular and smooth cells, like those of the sterile lemma of the wild type, still remained on the top region of the degenerated sterile lemmas (Fig. 1, Q–T). These results indicated that the degenerated sterile lemma in the mfs1-1 mutant had the identities of both sterile lemmas and rudimentary glumes.

It was found that 65% of mfs1-1 spikelets developed an extra hull (lemma/palea)-like organ (Fig. 1, I and K; Supplemental Fig. S1A). The wild-type lemma had four cell layers, silicified cells, fibrous sclerenchyma, spongy parenchymatous cells, and nonsilicified cells, and developed five vascular bundles. Compared with the lemma, the palea had three vascular bundles and consisted of two parts: the body of the palea (bop) and two marginal regions of the palea (mrp). The cellular structure of the bop was very similar to that of the lemma, but the mrp displayed a distinctive smooth epidermis, which lacked the epicuticular silicified thickening found in the lemma and bop (Fig. 1, B–E). In the mfs1-1 mutant, the extra hull-like organ showed a similar histological structure and had five vascular bundles, resembling the wild-type lemma (Fig. 1, J and N). We detected the mRNA levels of the lemma identity gene DROOPING LEAF (DL), the lemma and palea identity genes OsMADS1, OsMADS14, and OsMADS15, and the mrp identity gene OsMADS6 in mfs1-1 extra hull-like organs. Abundant levels of OsMADS1, OsMADS14, OsMADS15, and DL transcripts were detected, but no OsMADS6 expression was found (Fig. 1U). These results revealed that the extra hull-like organ had the identity of the lemma.

In mfs1-1 spikelets with extra lemma-like organs, 38% had no normal palea. Two palea-like organs were observed in the position normally occupied by the palea (Fig. 1, K and L; Supplemental Fig. S1A). Interestingly, each palea-like organ consisted of two mrps and a smaller bop with two vascular bundles (Fig. 1, L–O). The mrp and bop each had a texture similar to that of the wild-type palea (Fig. 1, M and N). OsMADS1, OsMADS14, and OsMADS15 were expressed normally (Fig. 1U), whereas DL was not expressed in the palea-like organs, similar to the case for the wild-type palea (Fig. 1U). OsMADS6 expression was more intense in the mfs1-1 palea-like organs than in wild-type paleae (Fig. 1U). These findings suggested that the palea-like organs were degenerated paleae, and the increased OsMADS6 expression in the palea-like organs was probably caused by the relative abundance of mrp tissues.

In 21% of the mfs1-1 spikelets, the palea was degenerated to various degrees (Supplemental Fig. S1A). Most of the degenerated palea contained the normal mrp and reduced bop (Supplemental Fig. S1, D and E). On a few occasions, the degenerated palea retained only mrp-like structures that contained a nonsilicified upper epidermis without trichomes and protrusions (Fig. 1, F–H). These results suggested that the development of mfs1-1 bop was severely affected.

Simultaneously, we also investigated the defects of the inner three whorls in the mfs1-1 mutant. In the florets (41%) with normal paleae, the identities and numbers of organs of the inner three whorls were not changed (Supplemental Table S2). In the florets (59%) with degenerated paleae, the numbers of organs of the inner three whorls were varied, but they retained their identities (Supplemental Table S2; Supplemental Fig. S1, F–I). Additionally, 81% of mfs1-1 spikelets possessed elongated rachillae (Fig. 1, F, I, Q, and S; Supplemental Fig. S1A).

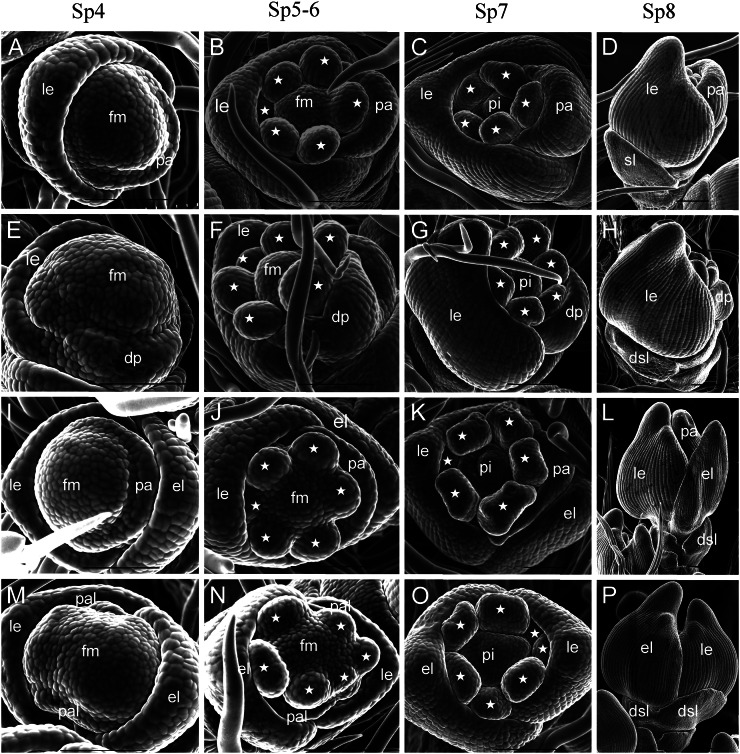

mfs1-1 Exhibited Abnormal Early Spikelet Development

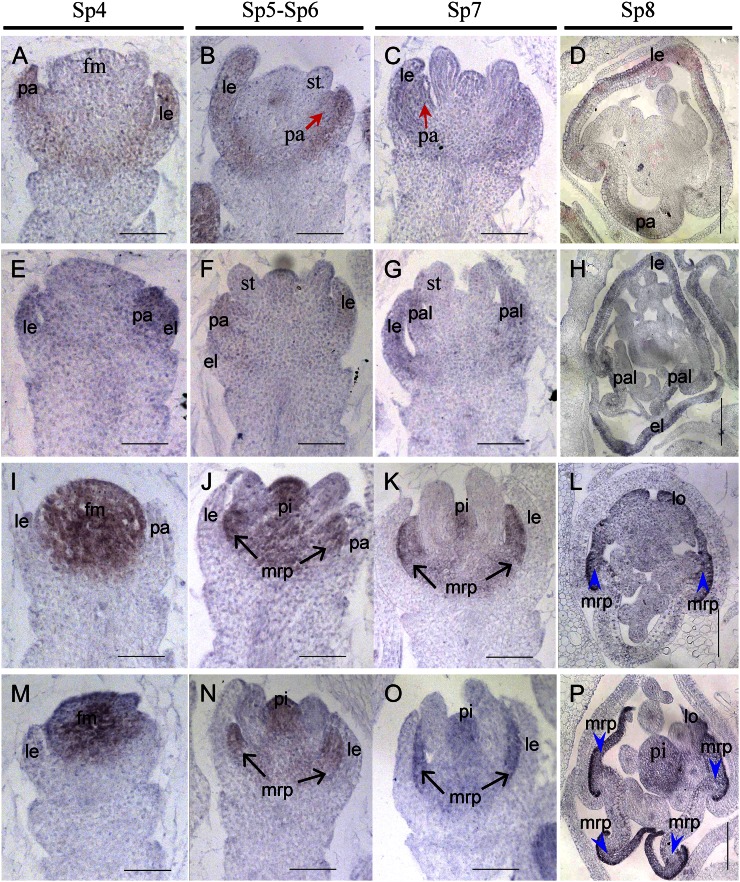

We examined young spikelets of the wild type and mutant at different developmental stages by scanning electron microscropy. During the spikelet 4 stage (Sp4), lemma and palea primordia of the wild-type flower started to develop, and the lemma had a bumped top and was larger than the palea (Fig. 2A). In the mfs1-1 mutant, some spikelets developed extra lemma-like organ primordia, and their paleae were either normal (Fig. 2I) or degenerated (Fig. 2M). At the same time, the floral meristem was enlarged in parts of the spikelets with degenerated paleae (Fig. 2M). Other spikelets had no extra lemma-like organ, whereas their palea primordia were reduced in size (Fig. 2E). During Sp5 and Sp6, the wild-type flower formed six spherical stamen primordia; the development of one stamen primordium on the lemma side was delayed, whereas the others developed synchronously (Fig. 2B). No significant differences were observed in those florets with an extra lemma-like organ and normal palea (Fig. 2J). However, in some florets with extra lemma-like organs and abnormal paleae, stamen development was not synchronous and the number of stamens varied (Fig. 2, N and O; Supplemental Fig. S1, F and G; Supplemental Table S2). In the florets with degenerated paleae, we found no obvious defects except in terms of the number of stamens (Fig. 2F; Supplemental Table S2). At the Sp7 and Sp8 stages (formation of pistil primordia), the lemma and palea progressed to a further stage of development. In the mfs1-1 mutant, apparent extra lemma-like organs and degenerated paleae were observed (Fig. 2, H, L, and P).

Figure 2.

Spikelets at early developmental stages in the wild type and mfs1-1. A to D, Wild-type spikelet at stages Sp4 (A), Sp5 to Sp6 (B), Sp7 (C), and Sp8 (D). E to P, mfs1-1 spikelet at stages Sp4 (E, I, and M), Sp5 to Sp6 (F, J, and N), Sp7 (G, K, and O), and Sp8 (H, L, and P). dsl, Degenerated sterile lemma; el, extra lemma-like organ; fm, floral meristem; le, lemma; lo, lodicule; pa, palea; pal, palea-like organ; pi, pistil; sl, sterile lemma. Asterisks indicate the stamens. Bars = 100 μm.

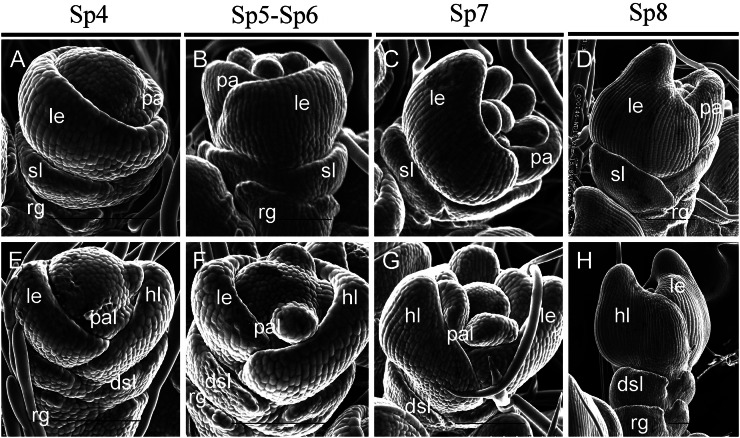

We also examined the sterile lemma at different developmental stages. At the Sp4 to Sp6 stages, the sterile lemma was larger than the rudimentary glume in the wild type (Fig. 3, A and B). In the mfs1-1 mutant, the size of the sterile lemma was similar to that of the rudimentary glume (Fig. 3, E and F). At the Sp7 and Sp8 stages, the sterile lemma differentiated drastically and was much larger than the rudimentary glume in the wild type (Fig. 3, C and D). However, the mfs1-1 sterile lemma was smaller than that of the wild type, resembling the rudimentary glume at these stages (Sp7 and Sp8; Fig. 3, G and H). Meanwhile, the epidermal cells started to elongate in sterile lemmas and still maintained their size in the rudimentary glume in the wild type (Fig. 3D), whereas their sizes were maintained in both the rudimentary glume and the sterile lemma of the mfs1-1 mutant (Fig. 3H). These results suggested that the identity of the mfs1-1 sterile lemma was affected, and the sterile lemma in the mfs1-1 mutant displayed a development pattern similar to that of the rudimentary glume.

Figure 3.

Sterile lemma development in wild-type and mfs1-1 spikelets at early stages. A to D, Development of the sterile lemma in the wild type at stages Sp4 (A), Sp5 to Sp6 (B), Sp7 (C), and Sp8 (D). E to H, Sterile lemma development in mfs1-1 at stages Sp4 (E), Sp5 to Sp6 (F), Sp7 (G), and Sp8 (H). dsl, Degenerated sterile lemma; hl, hull-like organ; le, lemma; pa, palea; pal, palea-like organ; rg, rudimentary glume; sl, sterile lemma. Bars = 100 μm.

Expression Patterns of Floral Organ Identity Genes during Early Stages of Flower Development

The expression patterns of DL, OsMADS1, and OsMADS6, which are known to be involved in the regulation of the lemma and palea identities, were investigated during the early stages of flower development.

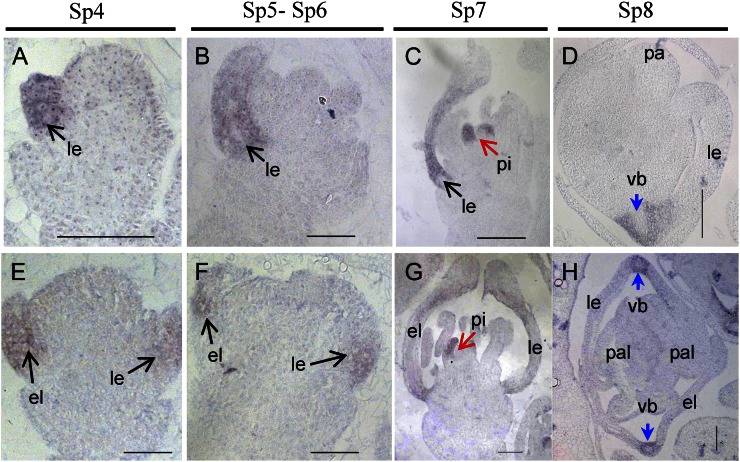

In wild-type flowers, DL was first expressed in the lemma primordia at stages Sp4 to Sp6 (Fig. 4, A and B) and then also in pistil primordia after SP7 (Fig. 4C), whereas DL transcripts were still retained in the lemma at Sp8 (Fig. 4D). In mfs1-1 flowers, the DL signals were pronounced in the extra lemma-like organ, in addition to the lemma and pistil (Fig. 4, E–H). These findings proved that the spikelets did indeed develop extra lemmas at the early stage of flower development.

Figure 4.

Expression of the DL gene in wild-type and mfs1-1 flowers. A to D, Wild-type flowers. E to H, mfs1-1 flowers. Columns 1 to 3 show longitudinal sections of flowers at stages Sp4 to Sp7, and column 4 shows transverse sections of flowers at stage Sp8. el, Extra lemma-like organ; le, lemma; pa, palea; pal, palea-like organ; pi, pistil; vb, vascular bundle. Bars = 50 μm.

In stages Sp4 to Sp8, OsMADS1 was expressed in the lemmas and paleae of wild-type florets (Fig. 5, A–D). In the mfs1-1 mutant, OsMADS1 signals were observed in the extra lemma-like organ, lemma, and palea (Fig. 5, E–H). In stages Sp4 to Sp7, OsMADS6 expression exhibited no significant differences between mfs1-1 and wild-type flowers and was detected in the floral meristem and primordia of the mrp, lodicule, and pistil (Fig. 5, I–K and M–O). At Sp8, in the transverse section of wild-type florets, OsMADS6 transcripts were found in the mrp, lodicule, and pistil (Fig. 5L). In the mfs1-1 mutant, OsMADS6 signals were detected in the two mrps of each palea-like organ, lodicule, and pistil (Fig. 5P). These results further suggested that the palea-like organs were derived from paleae in the mfs1-1 mutant.

Figure 5.

Expression of OsMADS1 and OsMADS6 in wild-type and mfs1-1 flowers. A to D, OsMADS1 expression in wild-type flowers. E to H, OsMADS1 expression in mfs1-1 flowers. I to L OsMADS6 expression in wild-type flowers. M to P, OsMADS6 expression in mfs1-1 flowers. Columns 1 to 3 show longitudinal sections of flowers at stages Sp4 to Sp7, and column 4 shows transverse sections of flowers at stage Sp8. el, Extra lemma-like organ; fm, floral meristem; le, lemma; lo, lodicule; pa, palea; pal, palea-like organ; pi, pistil. Bars = 50 μm.

Molecular Cloning and Identification of MFS1

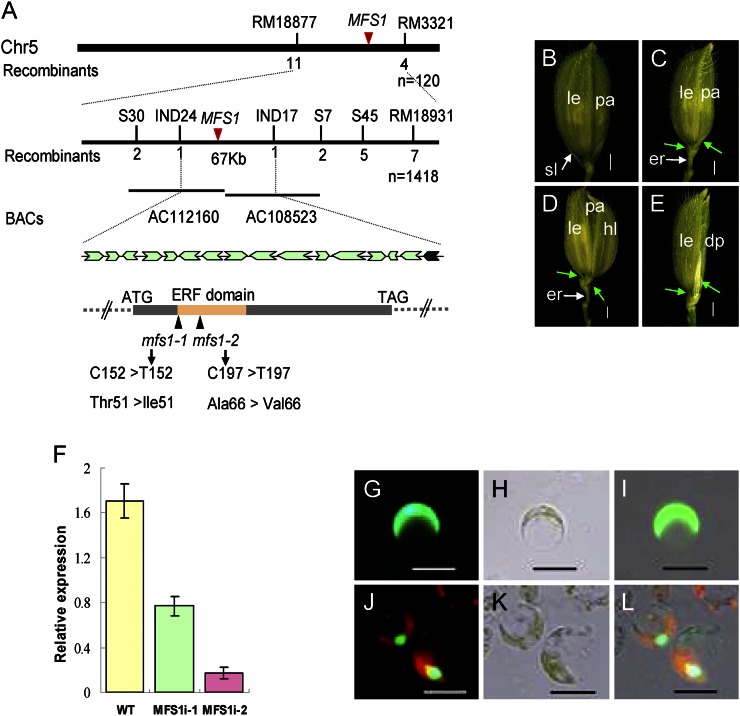

The MFS1 gene was previously mapped to a region of about 350 kb on chromosome 5 (Ren et al., 2012). Here, the location of MFS1 was narrowed to within a physical distance of 67 kb between the insertion/deletion markers IND17 and IND24 (Fig. 6A), in which there are 16 annotated genes (http://www.gramene.org/). Sequencing analysis identified a single-nucleotide substitution from C to T within a predicted AP2/ERF transcription factor (LOC_Os05g041760) in different positions of the two mfs1 alleles, causing amino acid mutations of Ala-66 to Val-66 in the mfs1-1 mutant and Thr-51 to Ile-51 in the mfs1-2 mutant (Fig. 6A). To test whether these mutations were causally linked to the mutant phenotype, the Os05g041760 wild-type genomic fragment that contained the coding sequence, 2,925 bp of sequence upstream of the start codon, and 938 bp of sequence downstream of the stop codon were transformed into mfs1-1. As a result of this, the mutant phenotypes were completely rescued in transgenic plants (Supplemental Fig. S2, A–C). We further performed RNA interference (RNAi) to silence MFS1 in the japonica cultivar ZH11. In the transgenic plants, the level of MFS1 transcript was greatly reduced (Fig. 6F) and pleiotropic spikelet defects similar to those of mfs1-1 were observed (Fig. 6, B–E). Taken together, these results confirmed that Os05g041760 is the MFS1 gene.

Figure 6.

Isolation of the MFS1 gene and subcellular localization of the MFS1 protein. A, Map position of the MFS1 locus. The relative positions of bacterial artificial chromosome clones (BACs) are shown. Below is the genomic structure of MFS1. The sites of the mutation in mfs1 are shown. Arrows indicate the sites of predicted genes in the IND17 to IND24 interval. B, Phenotype of ZH11 plants. C to F, RNAi analysis of MFS1 and phenotypes of transgenic plants. C to E, Phenotypes of RNAi transgenic plants. Green arrows indicate the degenerated sterile lemma. dp, Degenerated palea; er, elongated rachilla; hl, hull (lemma/palea)-like organ; le, lemma; pa, palea; sl, sterile lemma. F, MFS1 expression in RNAi transgenic plants. WT, Wild type. G to L, Analysis of the subcellular localization of the MFS1 protein using rice protoplasts. G to I, GFP fusion protein. G, Digital image control image. H, Bright-field image. I, Merged image of GFP fusion protein. J to L, MFS1-GFP. J, Digital image control image. K, Bright-field image. L, Merged image of MFS1-GFP fusion protein. Bars = 1,000 μm in B to E and 50 μm in G to L.

MFS1 Encodes an ERF Domain Protein

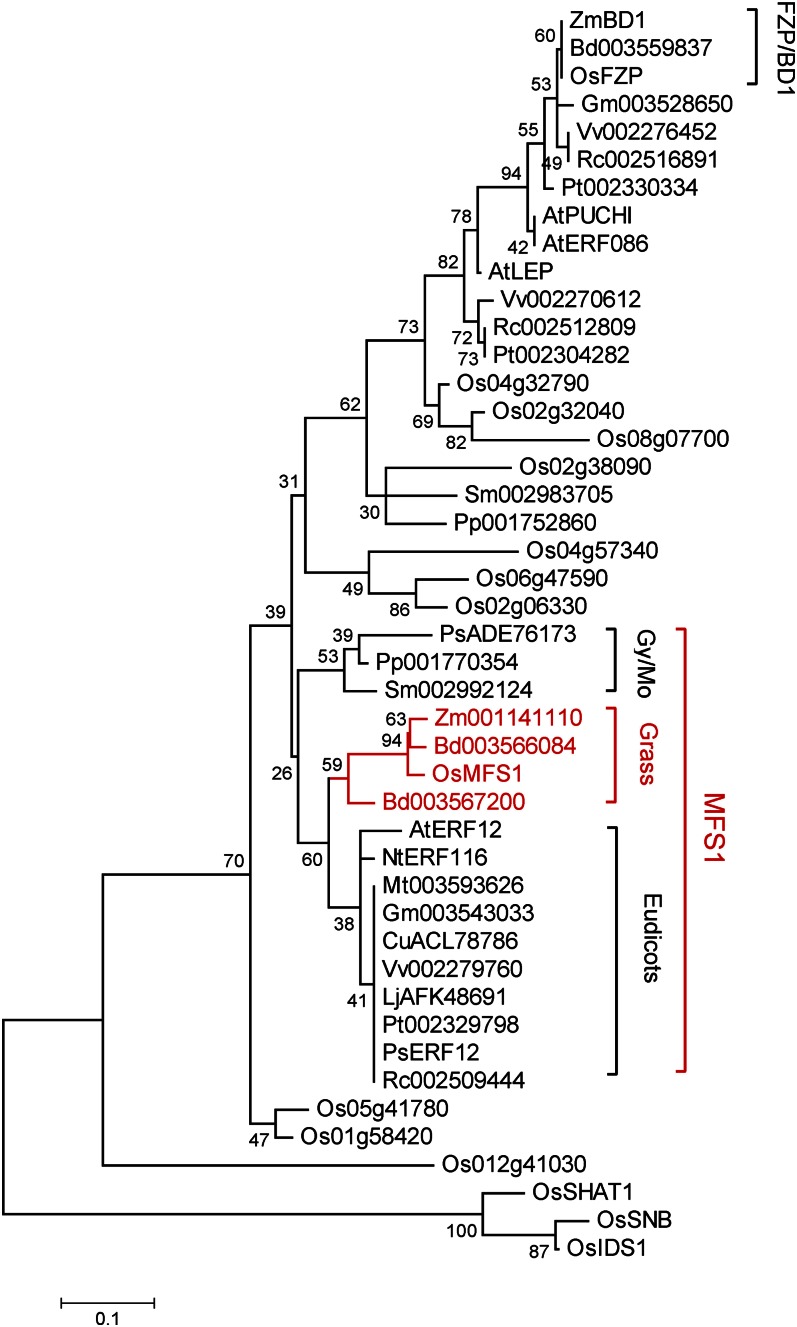

The AP2/ERF gene family is plant specific and includes four subfamilies: AP2, RAV, DREB, and ERF (Sharoni et al., 2011). Phylogenetic analysis showed that MFS1 and its orthologs from moss, gymnosperms, dicots, and grasses constitute an MFS1-like clade, whereas the well-known ERF domain proteins FZP and BD1 and their orthologs constitute another clade in the ERF subfamily (Fig. 7). These results suggested that MFS1-like and FZP/BD1-like genes diverged before the emergence of gymnosperms and that the MFS1-like genes differ from the well-known AP2/ERF genes. In addition, phylogenetic analysis also showed that the other known AP2 domain genes (SNB, OsIDS1, and SHAT1) have a distant evolutionary relationship with the MFS1-like and FZP/BD1-like genes.

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic tree of the MFS1 proteins. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood method based on the Jones-Taylor-Thornton matrix-based model. Gy/Mo, Gymnosperms and mosses. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Sequence analysis showed that all MFS1-like proteins contain a highly conserved ERF domain, located close to their N terminus. Meanwhile, a conserved C-terminal domain was identified in MFS1-like proteins from grasses and dicots, which share the DLNEPP185-190 motif. A unique site (V37) and a motif (SPWH132-135) were also identified in MFS1-like proteins from grasses (Supplemental Fig. S3). In addition, the MFS1 gene shared low sequence similarity with the known AP2/ERF genes outside the AP2/ERF domain (Supplemental Fig. S3).

Vectors that contained the MFS1ORF-GFP fusion protein, the SL1ORF-GFP fusion protein, and the single GFP protein were transiently expressed in rice protoplasts. The SL1ORF-GFP protein acted as a positive nuclear gene control (Xiao et al., 2009). Green fluorescence was detected in the nuclei of rice protoplasts for both MFS1ORF-GFP and SL1ORF-GFP fusion proteins (Fig. 6, J–L; Supplemental Fig. S2, D–F). In cells that expressed GFP alone, green florescence was observed uniformly throughout the cell, apart from the vacuole (Fig. 6, G–I). These results suggest that MFS1 encodes a nuclear protein that may act as a transcription factor.

Expression Patterns of MFS1

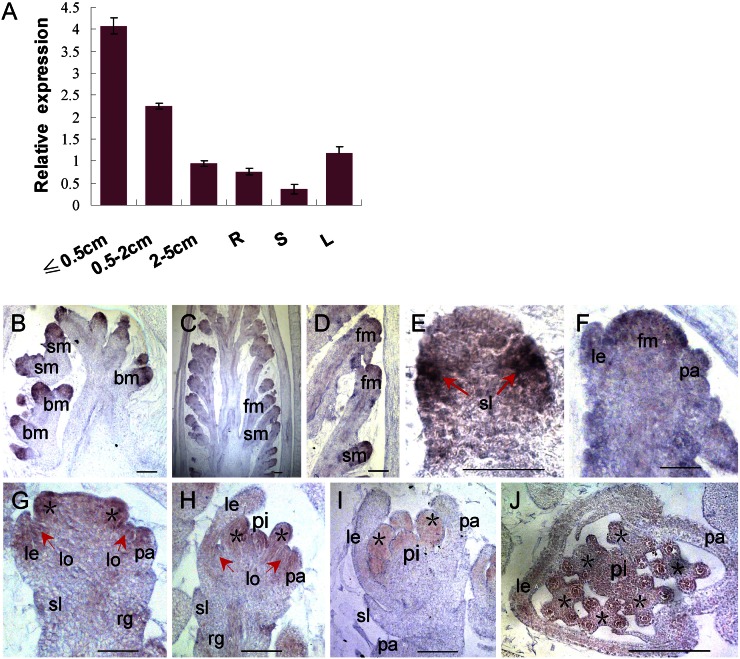

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qPCR) analysis showed that MFS1 was universally expressed in various tissues, including roots, stems, leaves, and panicles, with higher levels in young panicles (2 cm or less) than in the other tissues examined (Fig. 8A). Furthermore, the MFS1 expression pattern was investigated by in situ hybridization. First, MFS1 was highly expressed in the meristems of branches and spikelets (Fig. 8, B–D). Next, strong signals were observed at the sites of initiation of the sterile lemma primordium (Fig. 8E). When the lemma and palea primordia formed, abundant MFS1 transcripts were detected in the lemma, palea, and floral meristem (Fig. 8, D, F, and G). Subsequently, the expression of MFS1 was primarily restricted to the lemma, palea, lodicule, and stamen (Fig. 8, G and H). After the formation of pistil, MFS1 signals disappeared from the lemma and palea but were retained in the lodicule, stamen, and pistil (Fig. 8, I and J).

Figure 8.

Expression pattern of MFS1. A, MFS1 expression in different tissues as detected by qPCR. R, Root; S, stem; L, leaf. B to J, In situ hybridization in wild-type panicles and flowers using an MFS1 antisense probe. bm, Branch meristem; fm, floral meristem; le, lemma; lo, lodicule; pa, palea; pi, pistil; rg, rudimentary glume; sl, sterile lemma; sm, spikelet meristem. Asterisks indicate the stamens. Bars = 50 μm.

MFS1 Affects the Expression of Genes Related to Spikelet Development

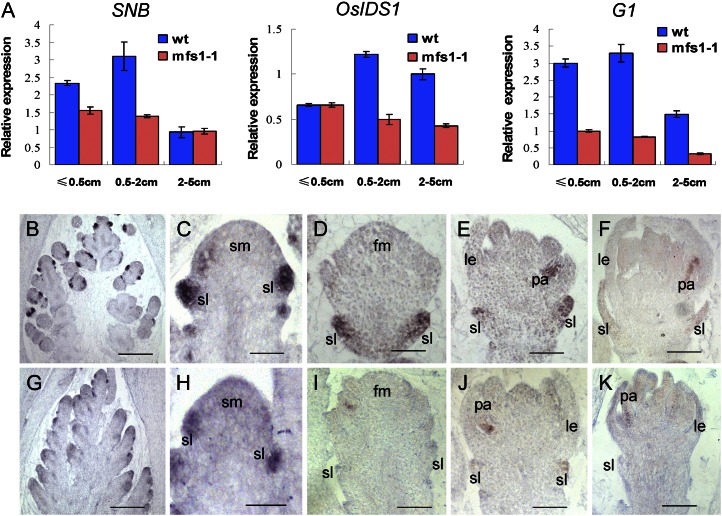

Given that the mfs1-1 mutant exhibited spikelet defects, we examined the expression levels of the IDS1-like genes SNB and OsIDS1, which are closely associated with the transition and determinacy of spikelet meristem in rice (Lee et al., 2007; Lee and An, 2012). SNB transcripts accumulated primarily in young panicles less than 2 cm long, and their levels were lower in the mfs1-1 mutant than in the wild type (Fig. 9A). Then, levels of SNB transcripts were dramatically decreased in panicles longer than 2 cm, and no difference in the levels of SNB expression was found between wild-type and mfs1-1 panicles with a length 2 to 5 cm (Fig. 9A). OsIDS1 transcripts were first detected in young panicles less than 0.5 cm, and they were more abundant in wild-type panicles between 0.5 and 5 cm in length (Fig. 9A). Compared with that in the wild type, OsIDS1 expression showed no obvious change in panicles with a length less than 0.5 cm, whereas it dramatically decreased in mfs1-1 panicles 0.5 to 5 cm long (Fig. 9A). These results imply that MFS1 positively regulated the expression of the IDS1-like genes SNB and OsIDS1.

Figure 9.

Expression of SNB, OsIDS1, and G1 in wild-type and mfs1-1 flowers. A, qPCR analysis of SNB, OsIDS1, and G1 in developing wild-type (wt) and mfs1-1 panicles at different stages. B to F, G1 expression in wild-type flowers. G to K, G1 expression in mfs1-1 flowers. le, Lemma; lo, lodicule; pa, palea; sl, sterile lemma; sm, spikelet meristem. Bars = 50 μm.

We used qPCR to examine the expression of the G1 gene, which has been shown to be involved in the specification of sterile lemma identity (Yoshida et al., 2009; Hong et al., 2010). In the wild type, a high level of G1 expression was detected in panicles shorter than 2 cm, but the mRNA levels were significantly reduced in those that were 2 to 5 cm (Fig. 9A). In the mfs1-1 mutant, G1 showed lower expression levels in young panicles shorter than 5 cm (Fig. 9A). In situ hybridization indicated that in the wild type, the G1 signals were strongly detected in sterile lemmas during the stage of sterile lemma primordia differentiation and formation, and subsequently, they decreased markedly when sterile lemmas started to elongate (Fig. 9, B–F). G1 expression was faint in the sterile lemma primordia of the mfs1-1 spikelet during the stages analyzed (Fig. 9, G–K), consistent with the results of qPCR analysis. These findings suggest that MFS1 positively regulates G1 expression.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we characterized a novel AP2/ERF domain gene, MFS1, that is involved in the regulation of spikelet meristem determinacy and floral organ identity in rice. MFS1 promotes the expression of the SNB, OsIDS1, and G1 genes involved in the development of spikelets.

MFS1 Affects Spikelet Meristem Determinacy

Most spikelets in mfs1-1 mutant plants each developed an extra lemma. About 27% of these spikelets produced normal florets after the extra lemmas arose, which suggested that these spikelets were composed of a terminal floret and a degenerated lateral floret that only contained the lemma. In the other spikelets with abnormal florets, two palea-like organs were observed, which corresponded to the extra lemma and the original lemma. Together with the development of a floral meristem that reached a larger than usual size at an earlier stage (Fig. 2M), these results imply that these spikelets tended to produce two florets, and the spikelet meristem determinacy was disturbed in the mfs1-1 mutant. Similarly, in the tongari-boushi1 (tob1) mutant, some spikelets had an extra lemma/palea-like organ between the sterile lemma and the original lemma (Tanaka et al., 2012). In the snb mutant, some spikelets developed supernumerary rudimentary glumes, extra lemma- or palea-like structures, or lateral florets before the terminal floret emerged (Lee et al., 2007). The snb+osids1 double mutant even produced more bract-like organs, including rudimentary glumes, lemmas, or paleae, than single mutants (Lee and An, 2012). These results suggest that SNB, OsIDS1, TOB1, and MFS1 regulate the fate of the spikelet meristem by ensuring the correct timing of the transition of the spikelet meristem to the terminal floral meristem. In contrast, the loss of spikelet meristem determinacy occurred before the formation of the rudimentary glume in snb and osids1 mutants but after the emergence of sterile lemmas in tob1 and mfs1-1 mutants. This suggested that MFS1 and TOB1 function later than SNB and OsIDS1. Additionally, decreases in the expression of SNB and OsIDS1 were found in mfs1-1 mutant young panicles, which suggested that MFS1 positively regulated the expression of SNB and OsIDS1.

MFS1 Specifies Sterile Lemma Identity

In the mfs1-1 mutant, the degenerated sterile lemma exhibited the identities of both the sterile lemma and the rudimentary glume. In the snb mutant, no sterile lemmas were found at sites where extra rudimentary glumes were present (Lee et al., 2007), which suggested the homeotic transformation of the sterile lemma to the rudimentary glume. In the osids1 mutant, one of the sterile lemmas was shown to be occasionally replaced by a rudimentary glume (Lee and An, 2012). SNB and OsIDS1 were also previously shown to encode an AP2/ERF domain protein (Lee et al., 2007; Lee and An, 2012). These results suggest that MFS1, SNB, and OsIDS1 confer important functions in the development of the sterile lemma. It was reported that G1/ELE, OsMADS34, and EG1 determined the identity of the sterile lemma. In these mutants, the sterile lemma was homeotically transformed into the lemma (Li et al., 2009; Yoshida et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2010; Hong et al., 2010; Kobayashi et al., 2010). These results suggest that G1/ELE, OsMADS34, and EG1 prevent the transformation of the sterile lemma to the lemma, whereas MFS1, SNB, and OsIDS1 prevent the degeneration of the sterile lemma to the rudimentary glume.

There have been two prevailing hypotheses on the origin and evolution of the sterile lemma (Takeoka et al., 1993). One states that a putative ancestor of the genus Oryza had a spikelet that contained a terminal floret and two lateral florets, which subsequently degenerated during evolution, leaving only the lemma (Arber, 1934; Kellogg, 2009).The sterile lemma thus would seem to be derived from morphological modification of the remnants of this lemma (Yoshida et al., 2009; Kobayashi et al., 2010). The other hypothesis suggests that the spikelet of Oryza spp. has only one floret, and the sterile lemma and rudimentary glume are universally regarded as severely reduced bract structures (Schmidt and Ambrose, 1998; Terrell et al., 2001; Hong et al., 2010). In the g1/ele1, osmads34, and eg1 mutants, the sterile lemmas were enlarged and transformed into lemmas, which supports the first hypothesis. In the mfs1-1 mutant, the sterile lemma was degenerated and acquired the identity of the rudimentary glume, which supports the second hypothesis. In fact, in most grass species, the spikelet lacks sterile lemma-like organs and only contains one or more florets and bract-like glume organs, which are considered to be equivalent to the rudimentary glumes of Oryza spp. (Takeoka et al., 1993; Yoshida et al., 2009; Hong et al., 2010). The bract-like glume organ resembles the lemma in size and structure in some grass species, such as maize and wheat (Kellogg, 2001; Yoshida et al., 2009), whereas it is severely reduced in Oryza spp. (Bommert et al., 2005; Li et al., 2009). Therefore, the lemma, sterile lemma, and rudimentary glume may be homologous structures.

MFS1 Regulates Palea Development

In grass flowers, the palea was thought to have a different identity and origin from the lemma. In general, the palea is considered homologous to the prophyll (the first leaf produced by the axillary meristem) that is formed on a floret axis, whereas the lemma corresponds to the bract (the leaf subtending the axillary meristem) that is formed on a spikelet axis (Kellogg, 2001; Ohmori et al., 2009). Recently, some evidence has indicated that the rice palea is an organ produced by congenital fusion of the bop and the mrp, which potentially have distinct origins (Francis, 1920; Cusick, 1966; Verbeke, 1992, Zanis, 2007). Specifically, first, the cellular structure of the bop was shown to be highly similar to that of the lemma but distinct from that of the mrp (Prasad et al.., 2005; Sang et al.., 2012). Second, the rice B-class mutant superwoman1 (spw1/osmads16) and MADS2+MADS4 double RNAi plants showed transformation of the lodicules into organs that resembled the mrp but not the bop. Moreover, mutants of Arabidopsis B-class genes undergo homeotic transformation of petals (equivalent to lodicules) into sepals (Nagasawa et al., 2003; Yadav et al., 2007; Yao et al., 2008). These findings suggest that the mrp, but not bop, is homologous to the sepal. In the depressed palea1 (dp1) mutant, the palea was shown to be replaced by two mrp-like structures and the bop was lost (Luo et al., 2005; Jin et al., 2011). In the retarded palea1 (rep1) mutant, the development of the bop was delayed, whereas overexpression of REP1 caused overdifferentiation of the mrp cells (Yuan et al., 2009). In the mfs1-1 mutant, the bop was degenerated in most florets and was even absent in a few cases. Additionally, recent studies revealed that CHIMERIC FLORAL ORGANS1 (CFO1/OsMADS32) and MOSAIC FLORAL ORGANS1 (MFO1/OsMADS6) were expressed in the mrp, the mutations of which resulted in transformation of the mrp into lemma-like or bop structures (Ohmori et al., 2009; Li et al., 2010; Sang et al., 2012). These results indicated that two parts of the palea are controlled by different regulatory pathways. Whereas MFS1, DP1, and REP1 determine bop identity, MFO1 and CFO1 are involved in the regulation of mrp identity. Consistent with these hypotheses, the phenotypes of the mfs1 palea suggest that the rice palea is an organ produced by the fusion of the mrp and bop, which have different origins.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we characterized the rice MFS1 gene, which belongs to a clade of unknown function in the AP2/ERF gene family. The mfs1 spikelets displayed extra lemmas, degenerated sterile lemmas, and paleae. These results suggest that MFS1 plays an important role in the regulation of spikelet determinacy and organ identity. Our data also reveal that MFS1 positively regulates the expression of G1 and the IDS1-like genes SNB and OsIDS1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

Two mutants of rice (Oryza sativa), mfs1-1 and mfs1-2, were identified from ethylmethane sulfonate-treated cultivar Jinhui 10. cv Jinhui 10 was used as the wild-type strain for phenotypic observation. All plants were cultivated in paddies in Chongqing and Hainan, China.

Map-Based Cloning of MFS1

The mfs1-1 mutant was crossed with cv Xinong1A, and 1,418 F2 plants with the mutational phenotype were selected and used as a mapping population. Initial gene mapping was conducted using simple sequence repeat markers from publicly available rice databases, including Gramene (http://www.gramene.org) and the Rice Genomic Research Program (http://rgp.dna.affrc.go.jp/publicdata/caps/index.html). Then, fine-mapping was performed using insertion/deletion markers developed from comparisons of genomic sequences from cv Xinong1A and Jinhui 10 in our laboratory. The sequences of primers used in the mapping and candidate gene analysis are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Microscopy Analysis

Panicles were collected at different developmental stages and fixed in 50% ethanol, 0.9 m glacial acetic acid, and 3.7% formaldehyde overnight at 4°C, dehydrated with a graded ethanol series, infiltrated with xylene, and embedded in paraffin (Sigma). The 8-μm-thick sections were transferred onto poly-l-Lys-coated glass slides, deparaffinized in xylene, and dehydrated through an ethanol series. The sections were stained sequentially with 1% safranine (Amresco) and 1% Fast Green (Amresco), then dehydrated through an ethanol series, infiltrated with xylene, and finally mounted beneath a coverslip. Light microscopy was performed using a Nikon E600 microscope. For scanning electron microscopy, fresh samples were examined using a Hitachi S-3400 scanning electron microscope with a –20°C cool stage. The stages of early spikelet development were the same as those defined previously (Ikeda et al., 2004).

RNA Isolation and qPCR Analysis

RNA from root, stem, leaf, inflorescence, and young flower was isolated using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit from Watson. The first strand of complementary DNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA using oligo(dT)18 primers in a 25-μL reaction volume using the SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Invitrogen). Reverse-transcribed RNA (0.5 μL) was used as a PCR template with gene-specific primers (Supplemental Table S3). The qPCR analysis was performed with an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System and the SYBR Supermix Kit (Bio-Rad). At least three replicates were performed, and mean values for the expression of each gene were used.

In Situ Hybridization

The 482-bp gene-specific MFS1 probe was amplified with the primers MFS1-F and MFS1-R and labeled using the DIG RNA Labeling Kit (SP6/T7) from Roche. Probes for the known floral organ genes were prepared using the same method. Pretreatment of sections, hybridization, and immunological detection were performed as described previously (Sang et al., 2012). The primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Vector Construction

For the complementation test, a 4,433-bp genomic fragment that contained the MFS1 coding sequence, coupled with the 2,925-bp upstream and 938-bp downstream sequences, was amplified using the primers MFS1com-F and MFS1com-R. The resulting PCR products were digested using XbaI and EcoRI and then inserted into the binary vector pCAMBIA1301. The recombinant plasmids were introduced into mfs1-1 by the Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation method as described previously (Sang et al., 2012). To make a construct for RNAi, we amplified a 267-bp fragment of MFS1 complementary DNA with the primers MFS1Ri-F (SpeI, KpnI) and MFS1Ri-R (SacI, BamHI), as shown in Supplemental Table S1. The resulting PCR products were first digested using SpeI and SacI and then ligated into vector pTCK303 (Wang et al., 2004) to obtain the intermediate vector. The PCR products were then digested using KpnI and BamHI and ligated into the intermediate vector. The recombinant plasmids were transformed into ZH11 plants by the A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation method. The primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Subcellular Localization

The coding region of MFS1 without the stop codon was amplified using the primer pair MFS1OE-F and MFS1OE-R which contain XbaI and BamHI sites, respectively (Supplemental Table S1). The fragment was cloned into the expression cassette 35S-GFP (S65T)-NOS (pCAMBIA1301) with appropriate modifications, which generated the MFS1-GFP fusion vector. The GFP and MFS1-GFP plasmids were transformed into rice protoplasts as described previously (Li et al., 2009). After 8 to 16 h of incubation at 28°C, GFP fluorescence was observed with a Nikon E600 microscope.

Protein Sequence and Phylogenetic Analysis

Protein sequences were obtained by searching GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) using the MFS1 sequence as a query. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 5.0 (Tamura et al., 2011). The tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood method based on the JTT matrix-based model with the lowest Bayesian Information Criterion scores (Jones et al., 1992; Tamura et al., 2011). Bootstrap support values for each node from 500 replicates are shown next to the branches (Felsenstein, 1985). The initial tree for the heuristic search was obtained automatically as follows. When the number of common sites was less than 100 or less than one-quarter of the total number of sites, the maximum parsimony method was used; otherwise, the bio-neighbor-joining method with Markov Cluster distance matrix was used. A discrete γ-distribution was used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites (five categories [+G], parameter = 0.6362). The tree was drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in terms of the number of substitutions per site.

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers: SNB (ABD24033), OsIDS1 (NM_001058244), G1/ELE (AB512480), DL (AB106553), OsMADS1 (NM_001055911), OsMADS6 (FJ666318), OsMADS14 (NM_001057835), and OsMADS15 (NM_001065255).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Investigation of mfs1 spikelets.

Supplemental Figure S2. Complementation test and subcellular localization.

Supplemental Figure S3. Protein sequence alignment of the closely related AP2/ERF genes.

Supplemental Table S1. Primers used in the study.

Supplemental Table S2. Distribution of the number of floral organs in the wild type and mfs1-1.

Glossary

- bop

body of the palea

- mrp

marginal regions of the palea

- qPCR

quantitative reverse transcription-PCR

- RNAi

RNA interference

- AP2/ERF

APETALA2/EREBP

References

- Ambrose BA, Lerner DR, Ciceri P, Padilla CM, Yanofsky MF, Schmidt RJ. (2000) Molecular and genetic analyses of the silky1 gene reveal conservation in floral organ specification between eudicots and monocots. Mol Cell 5: 569–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arber A (1934) The Gramineae: A Study of Cereal, Bamboo, and Grasses. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK [Google Scholar]

- Bommert P, Satoh-Nagasawa N, Jackson D, Hirano HY. (2005) Genetics and evolution of inflorescence and flower development in grasses. Plant Cell Physiol 46: 69–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley D, Ratcliffe O, Vincent C, Carpenter R, Coen E. (1997) Inflorescence commitment and architecture in Arabidopsis. Science 275: 80–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacharrón J, Saedler H, Theißen G. (1999) Expression of MADS box genes ZMM8 and ZMMI4 during inflorescence development of Zea mays discriminates between the upper and the lower floret of each spikelet. Dev Genes Evol 209: 411–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford HT (1987) Spikelet and floral morphology. In TR Soderstrom, KW Hilu, CS Campbell, ME Barkworth, eds, Grass Systematics and Evolution. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC, pp 21–30 [Google Scholar]

- Chuck G, Meeley RB, Hake S. (1998) The control of maize spikelet meristem fate by the APETELA2-like gene indeterminate spikelet1. Genes Dev 12: 1145–1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuck G, Meeley R, Hake S. (2008) Floral meristem initiation and meristem cell fate are regulated by the maize AP2 genes ids1 and sid1. Development 135: 3013–3019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen ES, Meyerowitz EM. (1991) The war of the whorls: genetic interactions controlling flower development. Nature 353: 31–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen ES, Nugent JM. (1994) Evolution of flowers and inflorescences. Development (Suppl) 107–116 [Google Scholar]

- Cusick F (1966) On phylogenetic and ontogenetic fusions. In EG Cutter, ed, Trends in Plant Morphogenesis. Longmans, Green, London, pp 170–183 [Google Scholar]

- Dreni L, Jacchia S, Fornara F, Fornari M, Ouwerkerk PB, An G, Colombo L, Kater MM. (2007) The D-lineage MADS-box gene OsMADS13 controls ovule identity in rice. Plant J 52: 690–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. (1985) Confidence limits on phylogenics: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39: 783–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis ME (1920) Book of Grasses. Doubleday, Page, Garden City, NY [Google Scholar]

- Gao XC, Liang WQ, Yin CS, Ji SM, Wang HM, Su X, Guo C, Kong HZ, Xue HW, Zhang DB. (2010) The SEPALLATA-like gene OsMADS34 is required for rice inflorescence and spikelet development. Plant Physiol 153: 728–740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong L, Qian Q, Zhu K, Tang D, Huang Z, Gao L, Li M, Gu M, Cheng Z. (2010) ELE restrains empty glumes from developing into lemmas. J Genet Genomics 37: 101–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K, Sunohara H, Nagato Y. (2004) Developmental course of inflorescence and spikelet in rice. Breed Sci 54: 147–156 [Google Scholar]

- Itoh J, Nonomura K, Ikeda K, Yamaki S, Inukai Y, Yamagishi H, Kitano H, Nagato Y. (2005) Rice plant development: from zygote to spikelet. Plant Cell Physiol 46: 23–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon JS, Jang S, Lee S, Nam J, Kim C, Lee SH, Chung YY, Kim SR, Lee YH, Cho YG, et al. (2000) leafy hull sterile1 Is a homeotic mutation in a rice MADS box gene affecting rice flower development. Plant Cell 12: 871–884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Luo Q, Tong H, Wang A, Cheng Z, Tang J, Li D, Zhao X, Li X, Wan J, et al. (2011) An AT-hook gene is required for palea formation and floral organ number control in rice. Dev Biol 359: 277–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM. (1992) The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput Appl Biosci 8: 275–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg EA. (2001) Evolutionary history of the grasses. Plant Physiol 125: 1198–1205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg EA. (2007) Floral displays: genetic control of grass inflorescences. Curr Opin Plant Biol 10: 26–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg EA. (2009) The evolutionary history of Ehrhartoideae, Oryzeae, and Oryza. Rice 2: 1–14 [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Maekawa M, Miyao A, Hirochika H, Kyozuka J. (2010) PANICLE PHYTOMER2 (PAP2), encoding a SEPALLATA subfamily MADS-box protein, positively controls spikelet meristem identity in rice. Plant Cell Physiol 51: 47–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DY, An G. (2012) Two AP2 family genes, Supernumerary bract (SNB) and Osindeterminate spikelet 1 (OsIDS1), synergistically control inflorescence architecture and floral meristem establishment in rice. Plant J 69: 445–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DY, Lee J, Moon S, Park SY, An G. (2007) The rice heterochronic gene SUPERNUMERARY BRACT regulates the transition from spikelet meristem to floral meristem. Plant J 49: 64–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Liang W, Jia R, Yin C, Zong J, Kong H, Zhang D. (2010) The AGL6-like gene OsMADS6 regulates floral organ and meristem identities in rice. Cell Res 20: 299–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Xiong G, Li R, Cui J, Tang D, Zhang B, Pauly M, Cheng Z, Zhou Y. (2009) Rice cellulose synthase-like D4 is essential for normal cell-wall biosynthesis and plant growth. Plant J 60: 1055–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Q, Zhou K, Zhao X, Zeng Q, Xia H, Zhai W, Xu J, Wu X, Yang H, Zhu L. (2005) Identification and fine mapping of a mutant gene for palealess spikelet in rice. Planta 221: 222–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcomber ST, Kellogg EA. (2004) Heterogeneous expression patterns and separate roles of the SEPALLATA gene LEAFY HULL STERILE1 in grasses. Plant Cell 16: 1692–1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcomber ST, Preston JC, Reinheimer R, Kossuth J, Kellogg EA (2006) Developmental gene evolution and the origin of grass inflorescence diversity In J Leebens-Mack, DE Soltis, PS Soltis, eds, Developmental Genetics of the Flower. Academic Press, New York, pp 383–421 [Google Scholar]

- Mimida N, Goto K, Kobayashi Y, Araki T, Ahn JH, Weigel D, Murata M, Motoyoshi F, Sakamoto W. (2001) Functional divergence of the TFL1-like gene family in Arabidopsis revealed by characterization of a novel homologue. Genes Cells 6: 327–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa N, Miyoshi M, Sano Y, Satoh H, Hirano H, Sakai H, Nagato Y. (2003) SUPERWOMAN1 and DROOPING LEAF genes control floral organ identity in rice. Development 130: 705–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa M, Shimamoto K, Kyozuka J. (2002) Overexpression of RCN1 and RCN2, rice TERMINAL FLOWER 1/CENTRORADIALIS homologs, confers delay of phase transition and altered panicle morphology in rice. Plant J 29: 743–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmori S, Kimizu M, Sugita M, Miyao A, Hirochika H, Uchida E, Nagato Y, Yoshida H. (2009) MOSAIC FLORAL ORGANS1, an AGL6-like MADS box gene, regulates floral organ identity and meristem fate in rice. Plant Cell 21: 3008–3025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad K, Parameswaran S, Vijayraghavan U. (2005) OsMADS1, a rice MADS-box factor, controls differentiation of specific cell types in the lemma and palea and is an early-acting regulator of inner floral organs. Plant J 43: 915–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao NN, Prasad K, Kumar PR, Vijayraghavan U. (2008) Distinct regulatory role for RFL, the rice LFY homolog, in determining flowering time and plant architecture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 3646–3651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe OJ, Bradley DJ, Coen ES. (1999) Separation of shoot and floral identity in Arabidopsis. Development 126: 1109–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren DY, Li YF, Wang Z, Xu FF, Guo S, Zhao FM, Sang XC, Ling YH, He GH. (2012) Identification and gene mapping of a multi-floret spikelet 1 (mfs1) mutant associated with spikelet development in rice. J Integr Agric 11: 1574–1579 [Google Scholar]

- Sang XC, Li YF, Luo ZK, Ren DY, Fang LK, Wang N, Zhao FM, Ling YH, Yang ZL, Liu YS, et al. (2012) CHIMERIC FLORAL ORGANS1, encoding a monocot-specific MADS box protein, regulates floral organ identity in rice. Plant Physiol 160: 788–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt RJ, Ambrose BA. (1998) The blooming of grass flower development. Curr Opin Plant Biol 1: 60–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharoni AM, Nuruzzaman M, Satoh K, Shimizu T, Kondoh H, Sasaya T, Choi IR, Omura T, Kikuchi S (2011) Gene structures, classification and expression models of the AP2/EREBP transcription factor family in rice. Plant Cell Physiol 52: 344–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussex IM, Kerk NM. (2001) The evolution of plant architecture. Curr Opin Plant Biol 4: 33–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeoka Y, Shimizu M, Wada T (1993) Panicles. In T Matsuo, K Hoshikawa, eds, Science of the Rice Plant, Vol I. Nobunkyo, Tokyo, pp 295–326 [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. (2011) MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28: 2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka W, Toriba T, Ohmori Y, Yoshida A, Kawai A, Mayama-Tsuchida T, Ichikawa H, Mitsuda N, Ohme-Takagi M, Hiranoa H. (2012) The YABBY gene TONGARI-BOUSHI1 is involved in lateral organ development and maintenance of meristem organization in the rice spikelet. Plant Cell 24: 80–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrell EE, Peterson PM, Wergin WP. (2001) Epidermal features and spikelet micromorphology in Oryza and related genera (Poaceae: Oryzeae). Smithsonian Contr Bot 91: 1–50 [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke JA. (1992) Fusion events during floral morphogenesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 43: 583–598 [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Chen C, Xu YY, Jiang RX, Han Y, Xu ZH, Chong K. (2004) A practical vector for efficient knockdown of gene expression in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Mol Biol Rep 22: 409–417 [Google Scholar]

- Weberling F (1989) Morphology of Flowers and Inflorescence. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H, Tang J, Li Y, Wang W, Li X, Jin L, Xie R, Luo H, Zhao X, Meng Z, et al. (2009) STAMENLESS 1, encoding a single C2H2 zinc finger protein, regulates floral organ identity in rice. Plant J 59: 789–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav SR, Prasad K, Vijayraghavan U. (2007) Divergent regulatory OsMADS2 functions control size, shape and differentiation of the highly derived rice floret second-whorl organ. Genetics 176: 283–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao SG, Ohmori S, Kimizu M, Yoshida H. (2008) Unequal genetic redundancy of rice PISTILLATA orthologs, OsMADS2 and OsMADS4, in lodicule and stamen development. Plant Cell Physiol 49: 853–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida A, Suzaki T, Tanaka W, Hirano HY. (2009) The homeotic gene long sterile lemma (G1) specifies sterile lemma identity in the rice spikelet. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 20103–20108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Z, Gao S, Xue DW, Luo D, Li LT, Ding SY, Yao X, Wilson ZA, Qian Q, Zhang DB. (2009) RETARDED PALEA1 controls palea development and floral zygomorphy in rice. Plant Physiol 149: 235–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn LM, Kong H, Leebens-Mack JH, Kim S, Soltis PS, Landherr LL, Soltis DE, Depamphilis CW, Ma H. (2005) The evolution of the SEPALLATA subfamily of MADS-box genes: a preangiosperm origin with multiple duplications throughout angiosperm history. Genetics 169: 2209–2223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanis MJ. (2007) Grass spikelet genetics and duplicate gene comparisons. Int J Plant Sci 168: 93–110 [Google Scholar]