Abstract

Knowledge accumulated on the regulation of iron (Fe) homeostasis, its intracellular trafficking and transport across various cellular compartments and organs in plants; storage proteins, transporters and transcription factors involved in Fe metabolism have been analyzed in detail in recent years. However, the key sensor(s) of cellular plant “Fe status” triggering the long-distance shoot–root signaling and leading to the root Fe deficiency responses is (are) still unknown. Local Fe sensing is also a major task for roots, for adjusting the internal Fe requirements to external Fe availability: how such sensing is achieved and how it leads to metabolic adjustments in case of nutrient shortage, is mostly unknown. Two proteins belonging to the 2′-OG-dependent dioxygenases family accumulate several folds in Fe-deficient Arabidopsis roots. Such proteins require Fe(II) as enzymatic cofactor; one of their subgroups, the HIF-P4H (hypoxia-inducible factor-prolyl 4-hydroxylase), is an effective oxygen sensor in animal cells. We envisage here the possibility that some members of the 2′-OG dioxygenase family may be involved in the Fe deficiency response and in the metabolic adjustments to Fe deficiency or even in sensing Fe, in plant cells.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, iron sensor, HIF (hypoxia-inducible factor), 2′-OG-dependent dioxygenase, prolyl 4-hydroxylase

INTRODUCTION

Iron is an essential micronutrient for plants although it is potentially toxic, when present in a free, non-complexed form. A recent review on that subject (Kobayashi and Nishizawa, 2012) details the knowledge accumulated on the regulation of plant Fe homeostasis, its intracellular trafficking and transport across cellular compartments and organs under various conditions of Fe supply, unveiling a complex net of molecular interactions. Beside the intensification of Fe-uptake strategies activated by plants under Fe-limiting conditions, root cells reprogram their metabolism to better cope with shortage of Fe (Vigani et al., 2012). Low Fe content triggers a high energy request to sustain the increased rate of Fe uptake from the soil, and at the same time it impairs the function of mitochondria and chloroplasts which provide energy to the cells. Thus, cells must increase the rate of alternative energy-providing pathways, such as glycolysis, Krebs cycle, or pentose phosphate pathway (López-Millán et al., 2000, 2012; Li et al., 2008; Vigani and Zocchi, 2009; Donnini et al., 2010; Rellán-Álvarez et al., 2010; Vigani, 2012a). To date, however, the sensors of plant “Fe status” triggering the signal transduction pathways, which eventually induce transcription factors such as the Arabidopsis FIT1, are still unknown and represent a challenging issue in plant science (Vigani et al., 2013). Efforts to fill up such gap of knowledge have been made by different research groups since years (Schmidt and Steinbach, 2000); recently, it has been demonstrated that localized Fe supply stimulates lateral root formation through the AUX1 auxin importer, which is proposed as a candidate for integrating the local Fe status in auxin signaling (Giehl et al., 2012).

2′-OG Fe(II)-DEPENDENT DIOXYGENASES AND PROLYL 4-HYDROXYLASES

It has been recently observed that some similarities might exist between the metabolic reprogramming occurring in Fe-deficient roots and that one occurring in tumor cells (Vigani, 2012b). In tumor cells, such reprogramming is known as “Warburg-effect” in which glucose is preferentially converted to lactate by enhancing glycolysis and fermentative reactions rather than completely oxidized by oxidative phosphorylation (OXOPHOS; Brahimi-Horn et al., 2007). Also in root cells a low Fe availability causes a decrease of OXOPHOS activity and induction of glycolysis and anaerobic reactions (Vigani, 2012b). The Warburg-effect in animal cells is mediated by hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF1), a heterodimeric complex whose α subunit is inducible by hypoxia. Under normoxic conditions, HIFα is post-translationally modified via the hydroxylation of proline residues by prolyl 4-hydroxylases (P4H); such modification leads to the proteasome-mediated degradation of HIFα. Under hypoxic conditions, however, such hydroxylation cannot occur because P4H enzymes belong to the 2-oxoglutarate Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenase family which have molecular oxygen and oxoglutarate as co-substrates; in other words, the lack of oxygen inhibits the P4H enzymatic activity, HIFα escapes degradation, it translocates to the nucleus where it can therefore form a dimer with HIFβ subunit; the complex then activates the cascade of hypoxia-responsive gene expression pathways (Myllyharju, 2003; Ken and Costa, 2006; Semenza, 2007).

Prolyl 4-hydroxylases are present in animal as well as in plant cells. In animal cells, P4H are classified into two categories: the collagen-type-P4H and the above cited HIF-P4H. The first class is localized within the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum and it catalyzes the hydroxylation of proline residues within -X-Pro-Gly- sequences in collagen and in collagen-type proteins (Myllyharju, 2003), thus stabilizing their triple helical structure at body temperature (Myllyharju, 2003). These P4Hs are α2β2 tetramers and their catalytic site is located in the α subunit (Myllyharju, 2003; Tiainen et al., 2005). Three aa residues, His-412, Asp-414, and His-483, are the binding sites for Fe(II) in the human α(I) subunit (Myllyharju, 2003). The second class of P4H is localized in cytoplasm and it is responsible for hydroxylation of a proline residue in the HIFα subunit, under normoxic conditions, as described above. The Km values of HIF-P4Hs for O2 are slightly above atmospheric concentration, making such proteins effective O2 sensors (Hirsilä et al., 2003). A novel role has also been uncovered for a human collagen-type-P4H, as regulator of Argonaute2 stability with consequent influence on RNA interference mechanisms (Qi et al., 2008).

Several genes similar to P4H are present in plants; for instance, 13 P4H have been identified in Arabidopsis and named AtP4H1–AtP4H13 (Vlad et al., 2007a,b); with the exception of AtP4H11 and AtP4H12, the three binding residues for Fe(II) (two His and one Asp) as well as the Lys residues binding the 2-oxoglutarate, are all conserved in such P4Hs (Vlad et al., 2007a). The different isoforms are more expressed in roots than in shoots and they show different pattern of expression in response to various stresses (hypoxia, anoxia, and mechanical wounding ; Vlad et al., 2007a,b).

Cloning and biochemical characterization of two of them, i.e., AtP4H1, encoded by At2g43080 gene (Hieta and Myllyharju, 2002) and At4PH2, encoded by At3g06300 gene (Tiainen et al., 2005) show that substrate specificity varies: recombinant AtP4H1 effectively hydroxylates poly(L-proline) and other synthetic peptides with Km values lower than those for AtP4H2, thus suggesting different physiological roles between the two. Recombinant AtP4H1 can also effectively hydroxylate human HIFα-like peptides and collagen-like peptides, whereas recombinant AtP4H2 cannot (Hieta and Myllyharju, 2002; Tiainen et al., 2005). Their Km for Fe(II) are 16 and 5 μM, respectively (Hieta and Myllyharju, 2002; Tiainen et al., 2005).

Two proteins belonging to the 2′-OG dioxygenase family, encoded by At3g12900 and At3g13610 genes, accumulate several folds in Fe-deficient roots, when compared to Fe-sufficient ones (Lan et al., 2011). The protein encoded by At3g13610 gene, named F6′H1, is involved in the synthesis of coumarins via the phenylpropanoid pathway, as it catalyzes the ortho-hydroxylation of feruloyl CoA, which is the precursor of scopoletin (Kai et al., 2008). Scopoletin and its β-glucoside scopolin accumulate in Arabidopsis roots and, at lower levels, also in shoots (Kai et al., 2006).

A severe reduction of scopoletin levels can be observed in the KO mutants for the At3g13610 gene (Kai et al., 2008). One of the responses to Fe deficiency, is the induction of the phenylpropanoid pathway (Lan et al., 2011). Phenolics can facilitate the reutilization of root apoplastic Fe (Jin et al., 2007a,b) and a phenolic efflux transporter PEZ1 located in the stele has been identified in rice (Ishimaru et al., 2011). The secretion of phenolic compounds can, moreover, selectively modify the soil microbial population in the surroundings of the roots, which in turn can favor acquisition of Fe by production of siderophores as well as auxin-like compounds (Jin et al., 2006, 2008, 2010).

Plant 2′-OG dioxygenases are also involved in synthesis of phytosiderophores such as Ids3 from barley, which is induced by Fe deficiency and it catalyzes the hydroxylation step from 2′-deoxymugeinic acid (DMA) to mugeinic acid (MA; Kobayashi et al., 2001).

2′-OG Fe(II)-DEPENDENT DIOXYGENASES, Fe DEFICIENCY RESPONSE AND METABOLIC REPROGRAMMING: IS THERE A COMMON LINK?

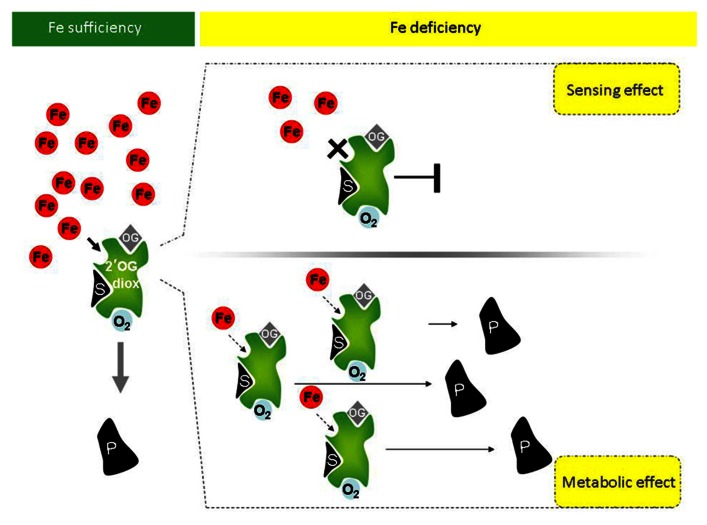

Given the above premises, it is possible that a link among P4H activity, and more generally among 2′-OG Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenase activities, the Fe deficiency responses and the metabolic reprogramming occurring during Fe deficiency exists in higher plants. If such a link exists for a given 2′-OG Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenase, at least two possible scenarios could be predicted for such enzyme (Figure 1):

FIGURE 1.

Potential involvement of plant 2′-OG-dioxygenases in Fe sensing, in the Fe deficiency responses and in the metabolic reprogramming occurring under Fe deficiency. Under Fe sufficiency, in presence of the co-factors O2 and oxoglutarate (OG), 2′-OG-dioxygenases (in green) can catalyze the dioxygenase reaction leading to production of product P from substrate S. Under Fe deficiency, however, at least two scenarios can occur, depending on the Km of a given 2′-OG-dioxygenase for Fe. If the Km is close to the physiological concentration of the labile iron pool (LIP; free redox-active Fe ions), upon reduction of Fe availability, the enzymatic activity of the 2′-OG-dioxygenase is drastically reduced or fully inhibited and the reduction or complete lack of enzymatic product can be itself a signal of “Fe deficiency” triggering the Fe deficiency response cascades (upper panel, right). If instead Km is far below the physiological LIP, the enzyme might still be active (lower panel, right). Not only, if transcriptional/translational up-regulation of such 2′-OG-dioxygenase takes place under Fe deficiency, then an increased total enzymatic activity can lead to higher production of product P (lower panel, right). Product P, in turn, could be involved in the Fe response/metabolic adjustments occurring under Fe deficiency.

(a) If, for a given sub-cellular localization, the Km of such enzyme for Fe is close to the physiological concentration of the LIP (labile iron pool, consisting of free redox-active Fe ions), then the enzyme activity is strongly affected by Fe fluctuations, similarly to the above described HIF-P4H, which is an effective sensor for O2 (Hirsilä et al., 2003). Upon reduction of Fe availability below the physiological LIP, its enzymatic activity should be indeed drastically reduced or fully inhibited; reduction or complete lack of enzymatic product might, in turn, triggers the “Fe deficiency” signaling. The enzyme might therefore act as true Fe sensor (Figure 1, upper panel, right).

Although the Fe-dependent transcriptional regulation of such an Fe sensor enzyme might be not expected, it cannot be excluded a priori: for example, chitin recognition is dependent not only on the presence of specific receptors, but also on the expression of extracellular chitinases, which are essential for the production of smaller chito-oligosaccharides from chitin hydrolysis, in animal (Gorzelanny et al., 2010; Vega and Kalkum, 2012) as well as in plant systems (Shibuya and Minami, 2001; Wan et al., 2008). These smaller, diffusible molecules induce, in turn, the expression of several defense protein, among which also chitinase activities. Chitinase is thus both an example of a crucial enzyme for the signal production but also an integral part of the response.

(b) If, for a given sub-cellular localization, the Km for Fe of such an enzyme is instead far below the physiological LIP, the enzyme might still be active under Fe deficiency. Additionally, if transcriptional/translational up-regulation occurs under Fe deficiency, accumulation of protein and increased total enzymatic activity might be observed. The enzyme might be involved in the Fe response/metabolic adjustment occurring under Fe deficiency, without being itself a Fe sensor (Figure 1, lower panel, right).

This second scenario is supported by the evidence that the Arabidopsis 2′-OG-dioxygenase F6′H1 (described in previous paragraph) which accumulates in Fe-deficient roots (Lan et al., 2011) is indeed possibly involved in the Fe response/metabolic adjustment occurring under Fe deficiency: Arabidopsis mutants KO for the At3g13610 gene (coding for F6′H1) have indeed altered root phenotype under Fe deficiency (I. Murgia, unpublished observations).

Such a link among 2′-OG Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenase activity, the Fe deficiency responses and the metabolic reprogramming occurring during Fe deficiency can be explored first by analyzing the transcriptional co-regulation of 2′-OG-dependent dioxygenase genes with genes involved in the Fe deficiency response or in the metabolic reprogramming. The bioinformatic approach of our choice was already described (Beekwilder et al., 2008; Menges et al., 2008; Berri et al., 2009; Murgia et al., 2011) and successfully applied in Arabidopsis and rice. Such analysis identifies genes which are co-regulated in large microarray datasets; in this case, it provides candidate genes potentially involved in Fe metabolism, among the 2′-OG-dioxygenase family members. Although transcript levels do not equal protein levels (or activities), there is nevertheless evidence for correlation between the two in many organisms (Vogel and Marcotte, 2012). This approach is not only simple on a genomic scale, but it has proved useful to identify candidate genes in the past, which were then validated by experimental approaches (e.g., Beekwilder et al., 2008; Murgia et al., 2011; Møldrup et al., 2012).

Arabidopsis possesses almost one hundred annotated 2′-OG dioxygenase genes which make such analysis not immediate; we therefore restricted the analysis to the AtP4H subclass (with the exclusion of AtP4H8, AtP4H12, and AtP4H13 because the corresponding genes were not available in the Affymetrix microarray data set most commonly used). As pivot bioinformatic analysis, we analyzed the correlation of such AtP4H subclass with two gene groups. The first group consisted of a list of 25 Fe-homeostasis/trafficking/transport related genes, described in recent reviews on this subject (Conte and Walker, 2011; Kobayashi and Nishizawa, 2012). The second group consisted of an equal number of genes coding for enzymes possibly involved in the metabolic adjustments under Fe deficiency, such as those catalyzing the synthesis of pyruvate (Pyr). It is indeed known that several glycolitic genes are overexpressed in roots of Fe-deficient plants (Thimm et al., 2001): different isoforms of hexokinase (HXK), phosphoglyceratekinase, enolase (ENO), phosphoglycerate mutase (iPGAM), were therefore considered. Also, genes coding for enzymes involved in the consumption of Pyr by non-OXOPHOS reactions and whose expression is affected by Fe deficiency, such as alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and malate dehydrogenase, were also considered (Thimm et al., 2001). Last, the genes coding for the four isoforms of Arabidopsis phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC; PPC1, 2, 3, 4; Sanchez et al., 2006) were also included in the second group, since PEPC is strongly induced in several dicotyledonous plants under Fe deficiency (Vigani, 2012a) and PEPC is supposed to play a central role in the metabolic reprogramming occurring in Fe-deficient root cells (Zocchi, 2006).

As positive controls, the two 2′-OG-dioxygenases encoded by At3g12900 and At3g13610 and accumulating in Fe-deficient roots (Lan et al., 2011) whereas, as negative control, the ferritin gene whose expression is known to be repressed under Fe deficiency (Murgia et al., 2002), were included. The full list of genes for which the correlation analysis has been performed, is reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of genes for which the correlation analysis with 2′-OG-dependent dioxygenases has been performed.

| Fe homeostasis genes | Metabolic genes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IRT1 | At4g19690 | HXK1 | At4g29130 |

| IRT2 | At4g19680 | HXK2 | At2g19860 |

| AHA2 | At4g30190 | HXK4 | At3g20040 |

| NAS1 | At5g04950 | HKL1 | At1g50460 |

| NAS2 | At5g56080 | HXL3 | At4g37840 |

| NAS3 | At1g09240 | PPC1 | At1g53310 |

| NAS4 | At1g56430 | PPC2 | At2g42600 |

| CYP82C4 | At4g31940 | PPC3 | At3g14940 |

| IREG2 | At5g03570 | PPC4 | At1g68750 |

| MTP3 | At3g58810 | PGK | At1g79550 |

| Popeye | At3g47640 | PGK1 | At3g12780 |

| Brutus | At3g18290 | LDH | At4g17260 |

| NRAMP3 | At2g23150 | ENO1 | At1g74030 |

| NRAMP4 | At5g67330 | ENOC | At2g29560 |

| FRO3 | At1g23020 | ENO2 | At2g36530 |

| FRO7 | At5g49740 | iPGAM | At1g09780 |

| FRD3 | At3g08040 | PGM | At1g78050 |

| ILR3 | At5g54680 | PDC2 | At5g54960 |

| YSL1 | At4g24120 | PDC3 | At5g01330 |

| ZIF1 | At5g13740 | G6PD4 | At1g09420 |

| VIT1 | At2g01770 | MMDH2 | At3g15020 |

| Fer1 | At5g01600 | mal dehydr family | At3g53910 |

| Fer2 | At3g11050 | mal dehydr family | At4g17260 |

| Fer3 | At3g56090 | mal dehydr family | At5g58330 |

| Fer4 | At2g40300 | ADH1 | At1g77120 |

| ADH transcrip factor | At2g44730 | ||

| ADH transcrip factor | At3g24490 | ||

Genes in the left column are known to be involved in the Fe deficiency response, in regulation of Fe homeostasis or Fe trafficking. Genes in the right column are involved in glycolysis or in the consumption of pyruvate by non-OXOPHOS reactions; genes coding for the four isoforms of Arabidopsis phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC; PPC1, 2, 3, 4) have been also included. IRT, iron-regulated transporter; AHA, Arabidopsis H+-ATPase; NAS, nicotianamine synthase; CYP82C4, cytochrome P450 82C4; IREG, ferroportin/iron-regulated; MTP3, metal tolerance protein; NRAMP, natural resistance-associated macrophage protein; FRO, ferric-chelate oxidase reductase; FRD, ferric reductase defective; ILR, IAA-leucine resistant; YSL, yellow stripe-like; ZIF, zinc induced facilitator; VIT, vacuolar iron transporter; Fer, ferritin; HXK1, hexokinase; HXL, hexokinase-like; PPC, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase; PGK, phosphoglyceratekinase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ENO, enolase; ENOC, cytosolic enolase; iPGAM, phosphoglycerate mutase; PGM, phosphoglycerate/bisphosphoglycerate mutase; PDC, pyruvate decarboxylase; G6PD4, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; MMDH, mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase; mal dehydr family, malate dehydrogenase family; ADH, alcohol dehydrogenase.

The resulting Pearson’s correlation coefficients, calculated by using either linear or logarithmic expression values (Menges et al., 2008; Murgia et al., 2011) are reported in Table 2, if above a defined threshold (≥0.60 or ≤-0.60); genes for which none of the Pearson’s coefficient fulfilled this condition, were not included in Table 2 (AtP4H3, AtP4H9, AtP4H10 and AtP4H11).

Table 2.

Correlation analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana 2′-OG dioxygenase genes with genes involved in Fe deficiency response or with genes possibly involved in metabolic reprogramming during Fe deficiency.

| 2′-OG-dioxyg | 2′-OG-dioxyg | P4H-1 | P4H-2 | P4H-4 | P4H-5 | P4H-6 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGI code | At3g12900 | At3g13610 | At2g43080 | At3g06300 | At5g18900 | At2g17720 | At3g28490 | ||||||||

| lin | log | lin | log | lin | log | lin | log | lin | log | lin | log | lin | log | ||

| IRT1 | At4g19690 | 0.69 | 0.23 | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.36 | 0.53 | -0.02 | 0.05 |

| AHA2 | At4g30190 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.76 | 0.71 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.76 | 0.79 | -0.07 | -0.07 |

| CYP82C4 | At4g31940 | 0.54 | 0.47 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.37 | -0.04 | -0.13 |

| IREG2 | At5g03570 | 0.73 | 0.42 | 0.79 | 0.59 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.41 | 0.51 | -0.02 | -0.08 |

| MTP3 | At3g58810 | 0.77 | 0.27 | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.40 | 0.58 | -0.04 | -0.10 |

| HXK4 | At3g20040 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.72 | 0.06 |

| HXL3 | At4g37840 | 0.01 | 0.05 | -0.06 | -0.03 | 0.13 | 0.05 | -0.08 | -0.06 | 0.32 | 0.11 | -0.05 | -0.06 | 0.66 | 0.35 |

| PPC1 | At1g53310 | 0.03 | -0.06 | 0.41 | 0.55 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.73 | 0.70 | -0.10 | -0.06 |

| PPC3 | At3g14940 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 0.69 | 0.58 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| PPC4 | At1g68750 | 0.01 | 0.08 | -0.04 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.05 | -0.05 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.78 | 0.21 |

| PGK1 | At3g12780 | -0.13 | -0.11 | -0.50 | -0.41 | -0.67 | -0.69 | -0.49 | -0.46 | -0.66 | -0.74 | -0.33 | -0.30 | -0.09 | -0.03 |

| ENO1 | At1g74030 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.72 | 0.59 | 0.37 | 0.31 | 0.67 | 0.59 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.54 | 0.49 | -0.05 | -0.01 |

| iPGAM | At1g09780 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.54 | 0.56 | -0.21 | -0.32 | 0.61 | 0.62 | -0.07 | -0.03 |

| Mal. d. fam. | At5g58330 | -0.19 | -0.23 | -0.56 | -0.49 | -0.70 | -0.67 | -0.61 | -0.61 | -0.59 | -0.60 | -0.47 | -0.47 | -0.08 | 0.02 |

For each gene pair, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient, from logarithmic or linear analysis, is reported. Coefficients with values ≥0.60 or ≤-0.60 are highlighted in gray.

In accordance with results obtained by iTRAQ (isobaric peptide tags for relative and absolute quantitation) analysis of Fe-deficient roots (Lan et al., 2011), both At3g12900 and At3g136100 show positive correlation with genes actively involved in the Fe deficiency response, such as iron-regulated transporter 1 (IRT1; Vert et al., 2002), ferric-chelate oxidase reductase (FRO2; Connolly et al., 2003) CYP82C4 (Murgia et al., 2011), ferroportin/iron-regulated (IREG2; Morrissey et al., 2009) metal tolerance protein (MTP3; Arrivault et al., 2006)(Table 2); viceversa, they show no significant correlation with the ferritin genes since their correlation values fall within the [-0.3 + 0.02] range (data not shown).

According to such results, the AtP4H genes could be divided into three classes:

Class 1: positive or negative correlation with metabolic genes only (At3g28490, At2g43080, and At5g18900).

Class 2: positive correlation with Fe-related genes and positive or negative correlation with metabolic genes (At2g17720 and At3g06300, beside the positive control At3g13610).

Class 3: no significant correlation (positive or negative) with any of the genes tested (At1g20270, At4g33910, At5g66060, At4g35820).

Genes in class 1 might be not involved in the plant response to improve Fe uptake and trafficking in order to alleviate Fe deficiency symptoms.

Genes in class 2 might be the ones linking the stimulation of Fe deficiency response with the metabolic adaptations triggered by Fe deficiency (Figure 1) whereas genes in class 3 might contain the candidate Fe sensor(s) (Figure 1).

Regarding the genes in class 2, it is interesting to notice that beside with the Fe-related genes, the positive control At3g13610 is positively correlated with PPC3 and ENO1, the At3g06300 gene coding for P4H2 (Tiainen et al., 2005) is positively correlated with PPC1, PPC3, ENO1, and also negatively correlated with a malate dehydrogenase family member whereas the At2g17720 gene coding for P4H5 is positively correlated with PPC1 and iPGAM (Zhao and Assmann, 2011).

Interestingly, PPC1 and PPC3 are mainly expressed in root tissues and their expression is affected by abiotic stress when compared with PPC2, which is considered to cover an housekeeping role (Sanchez et al., 2006), whereas ENO1 encodes the plastid-localized isoform of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP)-ENO (Prabhakar et al., 2009); PEP is further metabolized to Pyr by pyruvate kinase (PK). PEP and Pyr represent essential precursors for anaerobic reaction. PEP is fed into the schikimate pathway, which is localized within the plastid stroma (Herrmann and Weaver, 1999) and which is essential for a large variety of secondary products. Pyr can also act as precursor for several plastid-localized pathways, among which the mevalonate-independent way of isoprenoid biosynthesis (Lichtenthaler, 1999). Plastid-MEP (2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate) pathways might be responsible for the synthesis of a signal molecule putatively involved in the regulation of Fe homeostasis (Vigani et al., 2013).

Such analysis is preliminary and needs to be extended to all 2′-OG-dioxygenase gene family members. Genes candidate as Fe sensors can be further analyzed experimentally, insofar that loss-of function mutants lacking the “Fe sensing” function should display a Fe deficiency response, even in Fe-sufficient conditions (see Figure 1, upper panel, right).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Elucidation of nutrient sensing and signaling is a major issue in plant physiology and crop production, with potential impact in the design of new biofortification strategies for improving yields as well as the nutritional value of crops of interest (Murgia et al., 2012; Schachtman, 2012). In Arabidopsis, a major sensor of nitrate is the nitrate transporter NRT1.1, which is the first representative of plant “transceptors,” thus indicating their dual nutrient transport/signaling function (Gojon et al., 2011). Transceptors, whose feature is that transport and sensing activity can be uncoupled, have been described in animals and yeasts (Thevelein and Voordeckers, 2009; Kriel et al., 2011) and more active transceptors have been postulated also in plants (Gojon et al., 2011).Three major global challenges faced by agriculture are food and energy production as well as environmental compatibility (Ehrhardt and Frommer, 2012). Advancements in the area of nutrient sensing and signaling can positively contribute solutions to all these three challenges and the extensive analysis of the complete 2′-OG-dioxygenase gene family, based on pilot analysis described in the present perspective, could be a novel way to pursue these advancements.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Gianpiero Vigani and Irene Murgia were supported by FIRB, Futuro in Ricerca 2012 (project code RBFR127WJ9) funded by MIUR. Gianpiero Vigani was further supported by “Dote Ricerca”: FSE, Regione Lombardia. We are grateful to Prof. Shimizu Bun-Ichi (Graduate School of Life Science, Toyo University, Japan) for kindly providing Arabidopsis At3g13610 KO mutant seeds and to Luca Mizzi (Milano University, Italy) for developing the programs to compute the correlation coefficients.

REFERENCES

- Arrivault S., Senger T, Krämer U. (2006). The Arabidopsis metal tolerance protein AtMTP3 maintains metal homeostasis by mediating Zn exclusion from the shoot under Fe deficiency and Zn oversupply. Plant J. 46 861–879 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02746.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekwilder J., van Leeuwen W., van Dam N. M., Bertossi M., Grandi V., Mizzi L., et al. (2008). The impact of the absence of aliphatic glucosinolates on insect herbivory in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 3:e2068 10.1371/journal.pone.0002068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berri S., Abbruscato P., Faivre-Rampant O., Brasiliero A. C. M., Fumasoni I., Mizzi L., et al. (2009). Characterization of WRKY co-regulatory networks in rice and Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 9:120 10.1186/1471-2229-9-120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahimi-Horn M. C., Chiche J., Pouyessegur J. (2007). Hypoxia signalling controls metabolic demand. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19 223–229 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly E., Campbell N. H., Grotz N., Prichard C. L., Guerinot M. L. (2003). Overexpression of the FRO2 ferric chelate reductase confers tolerance to growth on low iron and uncovers posttranscriptional control. Plant Physiol. 133 1102–1110 10.1104/pp.103.025122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte S. S., Walker E. L. (2011). Transporter contributing to iron trafficking in plants. Mol. Plant 4 464–476 10.1093/mp/ssr015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnini S., Prinsi B., Negri A. S., Vigani G., Espen L., Zocchi G. (2010). Proteomic characterization of iron deficiency responses in Cucumis sativus L. roots. BMC Plant Biol. 10:268 10.1186/1471-2229-10-268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt D. W., Frommer W. B. (2012). New technologies for 21 century plant science. Plant Cell 24 374–394 10.1105/tpc.111.093302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giehl R. F. H., Lima J. E, von Wiren N. (2012). Localized iron supply triggers lateral root elongation in Arabidopsis by altering the AUX1-mediated auxin distribution. Plant Cell 24 33–49 10.1105/tpc.111.092973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gojon A., Krouk G., Perrine-Walker F., Laugier E. (2011). Nitrate transceptor(s) in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 62 2299–2308 10.1093/jxb/erq419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorzelanny C., Pöppelmann P., Pappelbaum K., Moerschbacher B. M., Schneider S. W. (2010). Human macrophage activation triggered by chitotriosidase-mediated chitin and chitosan degradation. Biomaterials 31 8556–8563 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann K. M., Weaver L. M. (1999). The shikimate pathway. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 50 473–503 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hieta R., Myllyharju J. (2002). Cloning and characterization of a low molecular weight prolyl 4-hydroxylase from Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 277 23965–23971 10.1074/jbc.M201865200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsilä M., Koivunen P., Günzler V., Kivirikko K. I., Myllyharju J. (2003). Characterization of the human prolyl 4-hydroxylases that modify the hypoxia-inducible factor. J. Biol. Chem. 278 30772–30780 10.1074/jbc.M304982200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y., Kakei Y., Shimo H., Bashir K., Sato Y., Uozumi N., et al. (2011). A rice phenolic efflux transporter is essential for solubilizing precipitated apoplastic iron in the plant stele. J. Biol. Chem. 286 24649–24655 10.1074/jbc.M111.221168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C. W., He Y. F., Tang C. X., Wu P., Zheng S. J. (2006). Mechanisms of microbially enhanced Fe acquisition in red clover (Trifolium pratense L.). Plant Cell Environ. 29 888–897 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01468.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C. W., Li G. X., Yu X. H., Zheng S. J. (2010). Plant Fe status affects the composition of siderophore-secreting microbes in the rhizosphere. Ann. Bot. 105 835–841 10.1093/aob/mcq071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C. W., You G. Y., He Y. F., Tang C., Wu P., Zheng S. J. (2007a). Iron deficiency-induced secretion of phenolics facilitates the reutilization of root apoplastic iron in red clover. Plant Physiol. 144 278–285 10.1104/pp.107.095794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C. W., He X. X., Zheng S. J. (2007b). The iron-deficiency induced phenolics accumulation may involve in regulation of Fe(III) chelate reductase in red clover. Plant Signal. Behav. 2 327–332 10.4161/psb.2.5.4502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C. W., You G. Y., Zheng S. J. (2008). The iron deficiency-induced phenolics secretion plays multiple important roles in plant iron acquisition underground. Plant Signal. Behav. 3 60–61 10.4161/psb.3.1.4902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai K., Mizutani M., Kawamura N., Yamamoto R., Tamai M., Yamaguchi H., et al. (2008). Scopoletin is biosynthesised via ortho-hydroxylation of feruloyl CoA by a 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 55 989–999 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03568.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai K., Shimizu B., Mizutani M., Watanabe K., Sakata K. (2006). Accumulation of coumarins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry 67 379–386 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ken Q., Costa M. (2006). Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1). Mol. Pharmacol. 70 1469–1480 10.1124/mol.106.027029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T., Nakanishi H., Takahashi M., Kawasaki S., Nishizawa N. K., Mori S. (2001). In vivo evidence that Ids3 from Hordeum vulgare encodes a dioxygenase that converts 2′deoxymugineic acid to mugineic acid in transgenic rice. Planta 212 864–871 10.1007/s004250000453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T., Nishizawa N. K. (2012). Iron uptake, translocation, and regulation in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 63 131–152 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriel J., Haesendonckx S., Rubio-Texeira M., Van Zeebroeck G., Thevelein J. M. (2011). From transporter to transceptor: signalling from transporter provokes re-evaluation of complex trafficking and regulatory control. Bioessays 33 870–879 10.1002/bies.201100100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan P., Li W., Wen T. N., Shiau J. Y., Wu Y. C., Lin W., et al. (2011). iTRAQ protein profile analysis of Arabidopsis roots reveals new aspects critical for iron homeostasis. Plant Physiol. 155 821–834 10.1104/pp.110.169508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Wu X., Hao S., Wang X., Ling H. (2008). Proteomic response to iron deficiency in tomato root. Proteomics 8 2299–2311 10.1002/pmic.200700942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler H. K. (1999). The 1-dideoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 50 47–65 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Millán A. F., Grusak M. A, Abadía J. (2012). Carboxylate metabolism change induced by Fe deficiency in barley, a strategy II plant species. J. Plant Physiol. 169 1121–1124 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Millán A. F., Morales F., Andaluz S., Gogorcena Y., Abadia A., De Las Rivas J., et al. (2000). Responses of sugar beet roots to iron deficiency. Changes in carbon assimilation and oxygen use. Plant Physiol. 124 885–898 10.1104/pp.124.2.885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menges M., Dóczi R., Okrész L., Morandini P., Mizzi L., Soloviev M., et al. (2008). Comprehensive gene expression atlas for the Arabidopsis MAP kinase signalling pathways. New Phytol. 179 643–662 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02552.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møldrup M. E., Salomonsen B., Halkier B. A. (2012). Engineering of glucosinolate biosynthesis: candidate gene identification and validation. Methods Enzymol. 515 291–313 10.1016/B978-0-12-394290-6.00020-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey J., Baxter I. R., Lee L., Lahner B., Grotz N., Kaplan J., et al. (2009). The ferroportin metal efflux proteins function in iron and cobalt homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21 3326–3338 10.1105/tpc.109.069401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgia I., Arosio P., Tarantino D., Soave C. (2012). Crops biofortification for combating “hidden hunger” for iron. Trends Plant Sci. 17 47–55 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgia I., Delledonne M., Soave C. (2002). Nitric oxide mediates iron-induced ferritin accumulation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 30 521–528 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01312.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgia I., Tarantino D., Soave C., Morandini P. (2011). The Arabidopsis CYP82C4 expression is dependent on Fe availability and the circadian rhythm and it correlates with genes involved in the early Fe-deficiency response. J. Plant Physiol. 168 894–902 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myllyharju J. (2003). Prolyl-hydroxylases, the key enzymes of collagen biosynthesis. Matrix Biol. 22 15–24 10.1016/S0945-053X(03)00006-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar V., Löttgert T., Gigolashvili T., Bell K., Flügge U. I, Häusler R. E. (2009). Molecular and functional characterization of the plastid-localized phosphoenolpyruvate enolase (ENO1) from Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 583 983–991 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi H. H., Ongushaha P. P., Myllyharju J., Cheng D., Pakkamen O., Shi Y., et al. (2008). Prolyl 4-hydroxylation regulates Argonaute2 stability. Nature 455 421–424 10.1038/nature07186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rellán-Álvarez R., Andaluz S., Rodríguez-Celma J., Wohlgrmuth G., Zocchi G., Álvarez- Fernández A., et al. (2010). Changes in the proteomic and metabolic profiles of Beta vulgaris root tips in response to iron deficiency and resupply. BMC Plant Biol. 10:120 10.1186/1471-2229-10-120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez R., Flores A., Cejudo F. J. (2006). Arabidopsis phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase genes encode immunologically unrelated polypeptides and are differentially expressed in response to drought and salt stress. Planta 223 901–909 10.1007/s00425-005-0144-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachtman D. P. (2012). Recent advances in nutrient sensing and signalling. Mol. Plant 5 1170–1172 10.1093/mp/sss109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt W., Steinbach S. (2000). Sensing iron-a whole plant approach. Ann. Bot. 86 589–593 10.1006/anbo.2000.1223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza G. L. (2007). Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) pathway. Sci. STKE 2007 cm8 10.1126/stke.4072007cm8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya N., Minami E. (2001). Oligosaccharide signalling for defence responses in plant. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 59 223–233 10.1006/pmpp.2001.0364 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thevelein J. M., Voordeckers K. (2009). Functioning and evolutionary significance of nutrient transceptors. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26 2047–2414 10.1093/molbev/msp168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimm O., Essigmann B., Kloska S., Altmann T., Buckhout T. J. (2001). Response of Arabidopsis to iron deficiency stress as revealed by microarray analysis. Plant Physiol. 127 1030–1043 10.1104/pp.010191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiainen P., Myllyharju J., Koivunen P. (2005). Characterization of a second Arabidopsis thaliana prolyl 4-hydroxylase with distinct substrate specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 280 1142–1148 10.1074/jbc.M411109200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega K., Kalkum M. (2012). Chitin, chitinase responses, and invasive fungal infections. Int. J. Microbiol. 2012:920459 10.1155/2012/920459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vert G., Grotz N., Dédaldéchamp F., Gaymard F., Guerinot M. L., Briat J. F., et al. (2002). IRT1, an Arabidopsis transporter essential for iron uptake from the soil and for plant growth. Plant Cell 14 1223–1233 10.1105/tpc.001388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigani G. (2012a). Discovering the role of mitochondria in the iron deficiency-induced metabolic responses of plants. J. Plant Physiol. 169 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigani G. (2012b). Does a similar metabolic reprogramming occur in Fe-deficient plant cells and animal tumor cells? Front. Plant Sci. 3:47 10.3389/fpls.2012.00047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigani G., Donnini S., Zocchi G. (2012). “Metabolic adjustment under Fe deficiency in roots of dicotiledonous plants,” in Iron Deficiency and Its Complication ed. Dincer Y. (Hauppauge: Nova Science Publishers Inc.) 1–27 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.09.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vigani G., Zocchi G. (2009). The fate and the role of mitochondria in Fe-deficient roots of strategy I plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 5 375–379 10.4161/psb.4.5.8344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigani G., Zocchi G., Bashir K., Philippar K., Briat J. F. (2013). Signal from chloroplasts and mitochondria for iron homeostasis regulation. Trends Plant Sci. 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.01.006[Epubaheadofprint]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlad F., Spano T., Vlad D., Daher F. B., Ouelhadj A., Kalaitzis P. (2007a). Arabidopsis prolyl hydroxylases are differently expressed in response to hypoxia, anoxia and mechanical wounding. Physiol. Plant. 130 471–483 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2007.00915.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlad F., Spano T., Vlad D., Daher F. B., Ouelhadj A., Fragkostefanakis S., et al. (2007b). Involvement of Arabidopsis Prolyl 4 hydroxylases in hypoxia, anoxia and mechanical wounding. Plant Signal. Behav. 2 368–369 10.4161/psb.2.5.4462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel C., Marcotte E. M. (2012). Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13 227–232 10.1038/nrg3185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan J., Zhang X. C., Stacey G. (2008). Chitin signaling and plant disease resistance. Plant Signal. Behav. 3 831–833 10.4161/psb.3.10.5916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z., Assmann S. M. (2011). The glycolytic enzyme, phosphoglycerate mutase, has critical roles in stomatal movement, vegetative growth, and pollen production in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 62 5179–5189 10.1093/jxb/err223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zocchi G. (2006). “Metabolic changes in iron-stressed dicotyledonous plants,” in Iron Nutrition in Plants and Rhizospheric Microorganisms eds Barton L. L., Abadía J. (Dordrecht: Springer; ) 359–370 10.1007/1-4020-4743-6_18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]