Abstract

Objective

Contingency management (CM) reduces drug use, but questions remain regarding optimal targets and magnitudes of reinforcement for specific patient subgroups. We evaluated the efficacy of CM reinforcing attendance in patients who initiated treatment with cocaine-negative samples, and of higher magnitude abstinence-based CM in patients who began treatment cocaine positive.

Methods

Initially cocaine-negative patients (n=333) were randomized to: standard care (SC), SC+CM reinforcing submission of negative samples with $250 in prizes ($250Abs), or SC+CM reinforcing attendance ($250Att). Initially cocaine-positive patients (n=109) were randomized to: SC, $250Abs, or higher magnitude CM ($560Abs).

Results

For initially cocaine-negative patients, $250Abs and $250Att were equally efficacious to SC in enhancing longest duration of abstinence during treatment (LDA); $250Att patients submitted lower proportions of negative samples when missing samples were considered missing, but these patients also attended more study sessions, provided more samples, and submitted a higher proportion of negative samples than SC patients when expected samples were analyzed, ps<.05. In initially cocaine-positive patients, both CM conditions increased proportions of negative samples relative to SC when missing samples were excluded from analyses, but only $560Abs was efficacious in increasing LDA and proportion of negative samples when expected samples were analyzed, ps<.05. Follow-ups revealed no differences in drug use among groups, but LDA was consistently associated with abstinence during follow-up, p<.05.

Conclusions

High magnitude abstinence-based reinforcement improved all abstinence outcomes in patients who began treatment while using cocaine. For patients initiating treatment abstinent, both attendance- and abstinence-based CM resulted in improvements on some measures.

Keywords: contingency management, cocaine, outpatient substance abuse treatment

Contingency management (CM) is highly efficacious for treating drug use disorders. Often, CM interventions reinforce submission of negative toxicology samples with vouchers exchangeable for retail goods and services (Higgins, Budney, Bickel, Foerg, Donham, & Badger, 1994; Higgins, Wong, Badger, Ogden, & Dantona, 2000b) or chances to win prizes (Petry et al., 2004; Petry et al., 2006a; Petry, Alessi, Hanson, & Sierra, 2007; Petry, Alessi, Marx, Austin, & Tardif, 2005a; Petry, Martin, Cooney, & Kranzler, 2000; Petry, Martin, & Simcic, 2005b; Petry et al., 2005c). A meta-analysis of psychosocial treatments concluded that CM was the intervention with the greatest effect size in treating substance use disorders (Dutra et al., 2008).

Although CM is efficacious, it is rarely implemented in practice. A primary obstacle is cost. Voucher CM typically provides up to $1000 in incentives, and reducing magnitudes of vouchers available renders CM less effective (Dallery, Silverman, Chutuape, Bigelow, & Stitzer, 2001; Higgins et al., 2007; Lussier, Heil, Mongeon, Badger, & Higgins, 2006). Prize CM usually arranges $250-$400 in expected maximal earnings and is efficacious over that range (Peirce et al., 2006; Petry et al., 2004, 2005a,b,c, 2006a, 2007). However, prize CM is also magnitude dependent, and reducing reinforcement likewise reduces efficacy (Petry et al., 2004), but primarily among patients with greater severity of drug use problems; patients with lower severity of drug use problems provided mostly negative samples regardless of reinforcement contingencies (Petry et al., 2004).

Adaptive research designs (Collins, Murphy, & Strecher, 2007; Murphy, Collins, & Rush, 2007; TenHave, Coyne, Salzer, & Katz, 2003) utilize aspects of patients' functioning as a basis for randomization to treatment conditions. These designs are gaining popularity in clinical research but have not been applied in CM study designs. Patients who initiate outpatient treatment while actively using drugs have a poor prognosis (Alterman et al., 1997; Alterman, McKay, Mulvaney, & McLellan, 1996) and may require greater magnitude reinforcement to achieve abstinence (Preston, Goldberger, & Cone, 1998; Silverman, Chutuape, Bigelow, & Stitzer, 1999; Stitzer et al., 2007). In re-analyzing data based upon sample results at treatment initiation, Stitzer et al. (2007) reported that CM that reinforced abstinence with up to $400 in prizes benefited only patients who began treatment with a negative sample and not patients with an initially positive sample. They concluded that more intensive interventions may be necessary in patients who begin treatment while still using drugs. Identifying a level of reinforcement magnitude sufficient to enhance outcomes in more severely drug dependent patients but still fairly low in cost could increase CM adoption.

Frequent toxicology testing is another obstacle to CM administration in practice. In addition to costs of the tests themselves, it is often not feasible for clinicians to collect samples two or three times per week (Petry & Simcic, 2002). Reinforcing attendance, rather than abstinence, may allow CM to be more readily integrated into practice, and may be equally beneficial for patients who initiate treatment while cocaine abstinent. Studies of patients enrolled in outpatient substance abuse treatment programs reveal low rates of drug use while such patients remain engaged in treatment. For example, in the National Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network (CTN) study (Petry et al., 2005c), over 88% of samples collected tested negative for cocaine, opioids and alcohol. Recent data suggest that CM that reinforces attendance can improve treatment engagement (Alessi, Hanson, Wieners, & Petry, 2007; Ledgerwood, Alessi, Hanson, Godley, & Petry, 2008; Petry, Martin, & Finocche, 2001; Sigmon & Stitzer, 2005), which in turn may be associated with reduced drug use (Simpson, Joe, & Broome, 2002).

However, reinforcing attendance alone could produce an undesired effect of patients attending treatment to obtain reinforcement while continuing to use drugs. Unlike CM protocols that reinforce abstinence, reinforcement values generally do not reset to lower values if drug use occurs when attendance alone is reinforced. This study tested the efficacy of a CM condition that reinforced attendance only and, at the same time, frequently assessed drug use to ascertain if patients would relapse and attend treatment while using substances.

The present study had two primary aims. The first was to compare the efficacy of two magnitudes of reinforcement in patients who began treatment with cocaine-positive samples. We expected that higher magnitude CM would be more efficacious than lower magnitude CM in improving durations of abstinence and proportions of negative samples in this subset of patients. The second purpose was to evaluate attendance-based CM in patients who initiated treatment while cocaine abstinent. We anticipated that attendance- and abstinence-based CM would be equally efficacious in engendering longer durations of objectively-confirmed abstinence than standard care in these patients. We also compared patients initiating treatment with cocaine-positive versus cocaine-negative samples, with the hypothesis that the former group would have poorer overall outcomes. Finally, we evaluated long-term effects of the interventions on abstinence at month 9 follow-up evaluations.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 442 outpatients initiating treatment at one of four community-based clinics in Hartford, CT, and Springfield, MA, regions between 2003 and 2007. The sample size of about 35 patients per group for evaluating effects of reinforcement magnitudes on durations of abstinence was estimated from studies varying magnitudes of reinforcement, which tend to have relatively large effect sizes of about d = .70 (Lussier et al., 2006; Petry et al., 2004). The sample size of about 110 patients per group for the comparison between targets of reinforcement was derived from Lussier et al (2006), as varying targets of reinforcement results in lower effect sizes than varying magnitudes of reinforcement; with a sample of 110 per group we could detect between group differences of about d = .38 in terms of engendering durations of objectively-confirmed abstinence. Patients were study eligible if they completed the study intake evaluation within 3 days of initiating outpatient treatment, were 18 years or older, spoke English, and met past-year Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) criteria for cocaine dependence. Dependence on other substances did not disqualify participants. Exclusion criteria were inability to understand the study, uncontrolled psychotic symptoms, active suicidality, or in recovery for pathological gambling. This latter criterion was employed because prize CM has an element of chance, although increases in gambling have not been observed (Petry & Alessi, 2010; Petry, Kolodner, Li, Peirce, Roll, Stitzer, & Hamilton, 2006b). The University's Institutional Review Board approved the study, and all participants signed written informed consent.

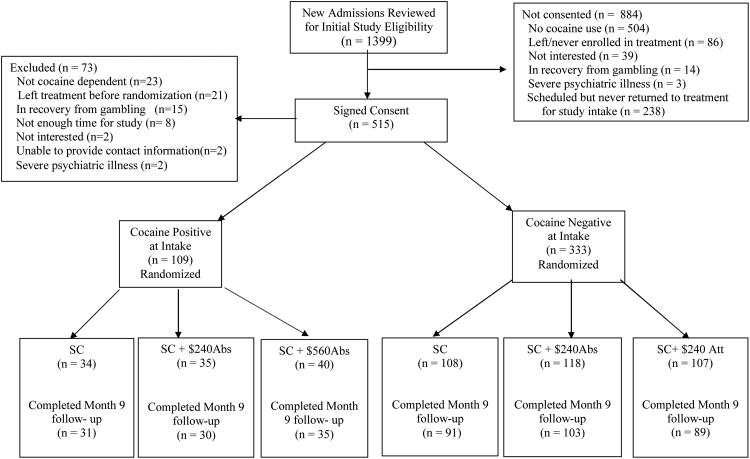

Research assistants (RAs) reviewed 1399 new admissions for initial eligibility. They consented 515 patients, and 73 were found ineligible, primarily related to not being cocaine dependent or failing to return to the clinic after initial screening (see Figure 1). In total, 442 were eligible, and 109 were randomized in the initially cocaine-positive study arm and 333 in the initially cocaine-negative arm. Because study urine samples were obtained following informed consent, which occurred 1-3 days after treatment initiation, classification into study arms reflected use or abstinence immediately prior to and/or during the initial days of treatment.

Figure 1. Flow Chart of Patients in Study.

Procedures

After obtaining informed consent, research assistants administered a 2-hour interview, which included the Addiction Severity Index (ASI; Bovasso, Alterman, Cacciola, & Cook, 2001; Kosten, Rounsaville, & Kleber, 1983), a reliable and valid instrument that evaluates severity of problems across 7 domains: employment, family/social, legal, drug, alcohol, medical, and psychiatric. Composite scores range from 0 to 1 on each domain, with higher scores reflecting greater problem severity.

Follow-up evaluations were scheduled 9 months after treatment initiation, and patients received $35 for submitting samples and completing the ASI. Figure 1 shows completion rates (> 83% per group), which did not differ by treatment group assignment, ps > .05.

Treatment group assignment

Research assistants randomly assigned patients to one of three conditions, which varied depending on the study arm in which they were enrolled. Two conditions were identical in both arms, and each arm had one unique condition. In the initially cocaine-positive arm, the three conditions were: standard care, $250 abstinence-based CM, and $560 abstinence-based CM. In the initially cocaine-negative arm, the three conditions were: standard care, $250 abstinence-based CM, and $250 attendance-based CM. Because the cocaine-positive arm applied larger magnitude reinforcers ($560) and enrollment in that arm necessitated submission of a cocaine-positive sample at treatment initiation, researchers never disclosed the two-arm nature of the study to patients or staff at the clinics. The consent form indicated patients had a chance of receiving one of four interventions, further outlined below.

Randomization occurred via two computerized urn randomization programs, one for each arm, at each clinic. In both arms, groups were balanced (Stout, Wirtz, Carbonari, & Del Boca, 1994) on gender and direct transfer from inpatient detoxification services or not. Blinding patients to conditions was impossible due to the nature of the interventions.

Standard care (SC)

Standard care at all clinics consisted of group therapy that included life skills training, relapse prevention, AIDS education and 12-step treatment. Intensive care (up to four hours/day, five days/week) was available for up to six weeks, and then intensity of care decreased. Aftercare consisted of one group per week for up to 12 months, but due to scheduling and personal commitments, not all patients attended aftercare.

In addition to SC, patients were expected to submit 21 urine and breath samples. Samples were scheduled three days per week during weeks 1-3 (e.g., Monday, Wednesday, Friday), two days per week during weeks 4-6 (e.g., Mondays and Fridays) and one day per week during weeks 7-12. This tapering schedule of sample submission mimicked reductions in clinical care over time. Research assistants screened observed urine specimens for cocaine and opioids using OnTrak TesTstiks (Varian, Inc., Walnut Creek, CA) and breath samples for alcohol using an Intoximeter Breathalyzer (Intoximeters, St. Louis, Mo). Research assistants congratulated patients when they tested negative. If results were positive, RAs encouraged patients to discuss use with clinical staff, but results were research data and not shared with clinical staff.

$250 Abstinence CM ($250Abs)

Patients in this condition received SC and sample monitoring described above. They also earned the opportunity to draw a card from a bowl, and possibly win a prize, every time they submitted negative samples. With the exception of study Day 1 (in which patients earned a draw if they tested negative for alcohol to expose patients to the reinforcement), patients needed to test negative for cocaine, opioids, and alcohol to earn draws. Consecutive submission of negative samples resulted in draws increasing by one up to a maximum of 10. Draws reset to one with submission of a sample positive for any of the three substances, refusal to submit a specimen, or an unexcused absence on a testing day. Once reset, number of draws increased to the previously highest level achieved following three consecutive negative samples. Only excused absences (e.g., doctor's or lawyer's appointments approved by primary therapists, hospitalizations) did not reset draws.

The bowl contained 500 cards, and 50% were associated with prizes. Of these, 219 were small prizes (choice of $1 fastfood coupons, toiletries, bus tokens, etc.), 30 were large prizes (choice of CDs, phone cards, watches, etc. worth up to $20), and one was a jumbo prize worth up to $100 (choice of stereo, television, etc.). Patients could choose immediately from a variety of prizes in each category. RAs replaced cards after drawings so chances remained constant, and patients were aware of probabilities. Patients who provided all 21 negative samples would earn 165 draws and an average expected maximum of $250 in prizes.

$560 Abstinence CM ($560Abs)

These patients received the same SC, sample monitoring, and total number of draws (165) for abstinence described above. The difference between this and the $250Abs condition related to probabilities of winning during an initial stage of abstinence. On study Day 1 and again on the first day they tested negative for cocaine, opioids, and alcohol concurrently, these patients drew from an “Initial Abstinence Bowl.” It contained 25 cards, and each was associated with a prize: 17 small, seven large, and one jumbo prize. Patients drew from the Initial Abstinence Bowl for their first negative specimen and continued drawing from this bowl so long as they remained abstinent for up to one month. Draws escalated by one for each successive negative sample, up to 10. Four weeks after submitting the first sample negative for all three substances, patients ceased drawing from the Initial Abstinence Bowl and began drawing from the standard 500-card bowl.

As in the $250Abs condition, positive samples or failure to submit a sample on a testing day resulted in no draws that day and reset draws to one for the next negative sample. Patients who reset during the one-month period after which they first achieved abstinence continued drawing from the Initial Abstinence Bowl, so long as they regained abstinence during the one-month period in which that bowl was in effect. If draws reset after the one-month initial abstinence period, then they selected from the standard bowl.

Attendance CM ($250Att)

These patients received SC and sample monitoring as above. Instead of earning draws for negative samples, these patients earned draws for attending treatment. Each day they attended a group session, they were also scheduled to meet with the RA to earn draws; draws escalated by one for each consecutive day of attendance, up to a maximum of seven draws per day. If they missed a session without a valid excuse, draws reset to one the next time they attended. Failure to attend a scheduled group on a given day (e.g., skipping one of three daily groups) also reset draws. If patients reset and then attended fully for three consecutive days, draws resumed to the highest level previously achieved. Before initiating the trial, we reviewed 200 patients' records of scheduled appointments, and maximum number of draws possible averaged 165 over 12 weeks. All draws were from the 500-slip prize bowl.

Data analyses

Analysis of variance, Kruskal-Wallis, and chi-square tests evaluated differences in baseline characteristics among patients assigned to the three conditions within each study arm, and between patients in the two study arms. When overall group effects were significant within a study arm, post-hoc tests compared each condition to the others in that arm, as these analyses are protected against type I error (Rosenthal & Rosnow, 1991). Data were log or square root transformed as needed to normalize distributions.

Outcome data were available for all randomized patients, and an intent-to-treat approach was employed. Analysis of variance evaluated treatment differences in duration of time in treatment, number of days in which patients attended study treatment sessions, longest consecutive period of objectively determined abstinence (LDA), and proportions of negative samples submitted. A week of consecutive abstinence was a 7-day period during which all scheduled samples tested negative. Because frequency of sample collection tapered over time, one week of abstinence was recorded for three consecutive negative samples during early phases, two during middle periods, and one during the last weeks. If a patient refused or missed a sample because of an unexcused absence, the string of abstinence was broken. Consistent with the reinforcement schedule, excused missed samples did not break a string of abstinence, but they were rare and averaged 1.4 (standard deviation (SD)=1.9) over the 12 weeks, and did not differ across groups, ps > .5.

Because LDA is impacted by missing samples and attrition, we also analyzed proportions of negative samples submitted. Proportion of negative samples was analyzed in two ways—first, including only submitted samples in the denominator, and second, assuming no missing samples (i.e., using 21 samples in the denominator). Analyzing abstinence in these different manners allows for a range of consideration regarding the impact of missing samples, from assuming missing samples are negative in the first case and not in the second.

For all analyses, we considered samples negative if they tested negative for cocaine, opioids, and alcohol. The vast majority of positive samples were positive for cocaine; in the cocaine-positive arm, 92.8% and 99.2% were opioid and alcohol negative, and in the cocaine-negative arm, 95.1% and 99.4% of samples were opioid and alcohol negative, respectively.

Logistic regression identified predictors of abstinence at month 9 as defined by negative urine and breath samples and no self-reports of cocaine, opioid, or alcohol use to intoxication in the past 30 days. In step 1, clinic, age, and gender were included; gender and clinic were included as categorical variables and age as a continuous variable. In step 2, treatment condition and LDA were entered. Because not all patients completed the follow-up, analyses were conducted twice—both excluding non-followed up patients, and including them as positive (see Figure 1 for numbers missing follow-ups). Analyses were performed on SPSS for Windows (Version 15), and we considered a two-tailed alpha < 0.05 significant.

Results

Demographic and baseline characteristics

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics for patients randomized to the three conditions in the two study arms. Only one variable differed significantly across groups within study arms. Among those in the cocaine-positive arm, ASI psychiatric scores were higher in those assigned to the $560Abs condition than the $250Abs condition.

Table 1. Demographic and Baseline Characteristics.

| Patients with a cocaine-positive sample at intake | Patients with a cocaine-negative sample at intake | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Variable | SC | $240Abs | $560Abs | Significance test | SC | $250Abs | $250Att | Significance test |

| (n = 34) | (n = 35) | (n = 40) | value (df), p-value | (n = 108) | (n = 118) | (n = 107) | Value (df), p-value | |

| Clinic% | χ2 (6) = 1.93, .93 | χ2 (6) = 3.79, .71 | ||||||

| A | 32.4 (11) | 28.6 (10) | 25.0 (10) | 44.4 (48) | 39.0 (46) | 41.1 (44) | ||

| B | 32.4 (11) | 42.9 (15) | 47.5 (19) | 10.2 (11) | 14.4 (17) | 16.8 (18) | ||

| C | 11.8 (4) | 8.6 (3) | 7.5 (3) | 28.7 (31) | 28.0 (33) | 29.9 (32) | ||

| D | 23.5 (8) | 20.0 (7) | 20.0 (8) | 16.7 (18) | 18.6 (22) | 12.1 (13) | ||

| Age | 37.4 (8.5) | 37.9 (7.0) | 38.4 (9.9) | F(2,106)=0.10, .90 | 36.4 (9.1) | 35.7 (9.1) | 37.4 (9.1) | F(2,330)=0.96, .39 |

| Male% | 44.1 (15) | 37.1 (13) | 30.0 (12) | χ2 (2) = 1.58, .45 | 46.3 (50) | 50.0 (59) | 44.9 (48) | χ2 (2) = 0.64, .73 |

| Years of education | 12.0 (2.3) | 11.8 (1.4) | 12.0 (2.4) | F(2,106)=0.15, .86 | 11.5 (2.2) | 12.0 (1.9) | 12.0 (1.9) | F(2,330)=2.24, .11 |

| Never been married% | 52.9 (18) | 54.3 (19) | 50.0 (20) | χ2 (2) = 0.15, .93 | 55.6 (60) | 58.5 (69) | 57.9 (62) | χ2 (2) = 0.22, .90 |

| Employed full time% | 35.3 (12) | 25.7 (9) | 20.0 (8) | χ2 (2) = 2.22, .33 | 35.2 (38) | 36.4 (43) | 35.5 (38) | χ2 (2) = 0.04, .98 |

| Income | $12,675 | $11,252 | $10,109 | F(2,106) =1.37, .26 | $10,416 | $12,873 | $11,440 | F(2,330)=0.19, .83 |

| (16,210) | (7,845) | (9,898) | (10,825) | (14,832) | (11,314) | |||

| Ethnicity% | χ2 (6) = 2.26, .89 | χ2 (6) = 4.34, .63 | ||||||

| African American | 38.2 (13) | 51.4 (18) | 20.0 (50.0) | 35.2 (38) | 29.7 (35) | 31.8 (34) | ||

| European American | 41.2 (14) | 25.7 (9) | 30.0 (12) | 46.3 (50) | 45.8 (54) | 50.5 (54) | ||

| Hispanic American | 14.7 (5) | 17.1 (6) | 15.0 (6) | 14.8 (16) | 22.0 (26) | 16.8 (18) | ||

| Other | 5.9 (2) | 5.7 (2) | 5.0 (2) | 3.7 (4) | 2.5 (3) | 0.9 (1) | ||

| Days of use in past 30 | ||||||||

| Cocaine | 10.9 (9.8) | 7.0 (7.3) | 11.1 (9.5) | F(2,106)=2.40, .10 | 2.7 (4.8) | 3.2 (4.7) | 3.3 (6.3) | F(2,316)=0.47, .62 |

| Heroin | 3.6 (8.1) | 1.8 (6.9) | 0.9 (3.0) | F(2,106)=1.76, .18 | 0.6 (2.5) | 0.7 (3.1) | 1.0 (4.2) | F(2,316)=0.47, .63 |

| Alcohol | 6.4 (9.4) | 5.5 (8.4) | 5.0 (7.7) | F(2,106)=0.26, .77 | 3.2 (6.1) | 3.2 (6.2) | 2.8 (6.1) | F(2,316)=0.15, .86 |

| Inpatient transfer% | 8.8 (3) | 8.6 (3) | 5.0 (2) | χ2 (2) = 0.51, .78 | 23.1 (25) | 25.4 (30) | 20.6 (22) | χ2 (2) = 0.75, .69 |

| Addiction Severity Index Scores * | ||||||||

| Medical | 0.11 (0.66) | 0.00 (0.58) | 0.00 (0.74) | χ2 (2) = 0.90, .64 | 0.00 (0.65) | 0.00 (0.63) | 0.00 (0.63) | χ2 (2) = 0.37, .83 |

| Employment | 0.87 (0.25) | 0.90 (0.25) | 0.75 (0.44) | χ2 (2) = 3.16, .21 | 0.92 (0.41) | 0.85 (0.37) | 0.79 (0.50) | χ2 (2) = 0.31, .86 |

| Alcohol | 0.20 (0.44) | 0.18 (0.39) | 0.14 (0.43) | χ2 (2) = 0.49, .78 | 0.15 (0.40) | 0.16 (0.41) | 0.18 (0.40) | χ2 (2) = 0.31, .86 |

| Drug | 0.25 (0.12) | 0.26 (0.16) | 0.28 (0.19) | χ2 (2) = 1.41, .50 | 0.18 (0.10) | 0.19 (0.11) | 0.18 (0.14) | χ2 (2) = 1.07, .59 |

| Legal | 0.00 (0.21) | 0.00 (0.30) | 0.00 (0.25) | χ2 (2) = 1.12, .57 | 0.00 (0.13) | 0.00 (0.17) | 0.00 (0.15) | χ2 (2) = 0.11, .95 |

| Family/social | 0.03 (0.22) | 0.02 (0.23) | 0.10 (0.23) | χ2 (2) = 0.17, .92 | 0.20 (0.33) | 0.10 (0.25) | 0.05 (0.26) | χ2 (2) = 3.37, .17 |

| Psychiatric | 0.29 ab (0.53) | 0.09a (0.38) | 0.34b (0.43) | χ2 (2) = 6.60, .04 | 0.32 (0.45) | 0.31 (0.43) | 0.36 (0.43) | χ2 (2) = 2.39, .30 |

Notes. Values are means (with standard deviations in parentheses) unless noted.

Values are percentages (n).

Kruskal-Wallis test; and values are medians (with interquartile ranges in parentheses)

Values with different superscripts next to them differ significantly from one another in post-hoc tests. SC=Standard Care; Abs=Abstinence-based CM; Att=Attendance-based CM

In statistically comparing patients in the two study arms (data not shown), the only demographic characteristic that differed was ethnicity, χ2 (3) = 12.13, p < .01. More European Americans and fewer African Americans were in the cocaine-negative than in the cocaine-positive arm. Participation in the cocaine-positive arm was also related to greater severity of drug problems as assessed by ASI drug composite scores, χ2 (1) = 33.75, p < .001, and past-month self-reported days of cocaine, heroin, and alcohol use, F (1,440) = 87.61, 6.63, and 11.32, respectively, ps <.001.

Treatment retention and attendance

Table 2 shows no differences in weeks retained in treatment in either study arm or number of sessions attended across groups in the cocaine-positive arm. However, among patients in the cocaine-negative arm, those assigned to the $250Att condition attended significantly more sessions than those in either other condition, with patients in SC attending the fewest sessions. The mean (SD) sessions attended for patients in the cocaine-positive arm (regardless of condition; data not shown directly in tables) was 9.8 (6.4), and for those in the cocaine-negative arm it was 14.1 (7.2), F (1,440) = 31.32, p < .001.

Table 2. Primary Outcome Variables.

| Patients with a cocaine-positive sample at intake | Patients with a cocaine-negative sample at intake | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Variable | SC | $240Abs | $560Abs | Significance test | SC | $250Abs | $250Att | Significance test |

| (n = 34) | (n = 35) | (n = 40) | value (df), p-value | (n = 108) | (n = 118) | (n = 107) | Value (df), p-value | |

| Retained in treatment (weeks) | 4.8 (3.2) | 4.3 (2.9) | 6.0 (4.1) | F (2,106) = 1.05, .35 | 6.0 (4.0) | 6.0 (3.7) | 5.4 (3.6) | F (2, 330) = 0.80, .45 |

| Number of sessions attended | 8.7 (6.4) | 9.2 (6.1) | 11.2 (6.6) | F (2,106) = 1.54, .22 | 11.4a (5.7) | 13.8b (6.4) | 17.1c (8.3) | F (2, 330) = 18.41, .000 |

| Samples submitted | 8.6 (6.1) | 9.3 (6.1) | 11.3 (6.7) | F (2,106) = 1.80, .17 | 11.3a (5.6) | 13.8b (6.3) | 14.1b (6.3) | F (2, 330) = 6.98, .000 |

| Proportion of samples submitted negative | 30.1a (35.1) | 52.7b (35.2) | 54.8b (35.7) | F (2,105) = 5.20, .007 | 91.9a (13.4) | 90.2a (20.3) | 84.1b (24.3) | F (2, 329) = 4.59, .01 |

| Proportion of expected samples negative | 16.0 a (24.2) | 28.8 ab (29.1) | 38.8 b (35.6) | F (2,105) = 4.08, .02 | 50.2a (26.9) | 61.6b (31.9) | 58.5b (32.5) | F (2,329) = 4.10, .02 |

| Longest duration of abstinence (weeks) | 1.1a (2.1) | 2.0ab (3.1) | 3.6b (4.3) | F (2,106) = 3.00, .05 | 3.9a (3.5) | 6.0b (4.3) | 5.3b (4.4) | F (2, 330) = 7.62, .001 |

Notes. All values are means (with standard deviations in parentheses). All abstinence variables refer to samples testing negative for cocaine, opioids, and alcohol. Values with different superscripts next to them differ significantly from one another in post-hoc tests. SC = Standard Care; Abs = Abstinence-based CM; Att = Attendance-based CM.

Abstinence during treatment

Abstinence outcomes differed across groups in both arms of the study (Table 2). In the initially cocaine-positive study arm, using actual number of samples collected, both CM conditions significantly increased proportions of negative samples submitted relative to SC, and the two CM conditions did not differ when missing samples were not considered in the denominator. When expected samples were used in the denominator, only patients in the $560Abs condition demonstrated increased proportions of negative samples compared to those in SC. Patients assigned to $560Abs also achieved significantly longer durations of abstinence than those assigned to SC, while those assigned to $250Abs achieved intermediary periods of abstinence, which did not differ from either of the other conditions.

Among patients in the cocaine-negative arm, sample submission rates differed across treatment conditions, with $250Att patients submitting the most samples. Using the actual number of samples submitted in the denominator (and noting that $250Att patients submitted the most samples), mean proportion of negative samples was lowest among patients assigned to $250Att (Table 2). This lower proportion of negative samples may reflect a greater tendency to come to treatment and submit a sample after using, or more patients in this condition achieving relatively low rates of during treatment abstinence. Between 16-17% of SC and $250Abs patients submitted fewer than 80% negative samples, compared with 28.0% of $250Att patients. However, when the denominator included the number of expected samples in the denominator, both the $250Att and $250Abs conditions increased proportion of negative samples relative to SC. Also, patients receiving $250Att achieved durations of objectively-confirmed abstinence as long as those receiving $250Abs, and both groups attained significantly longer durations of objectively-confirmed abstinence than those receiving SC.

When number of submitted samples was used in the denominator, proportions of negative samples were high overall in the cocaine-negative arm, with a mean (SD) of 88.8% (20.1) of samples testing negative for all three substances, compared with 46.6% (36.7) for those in the cocaine-positive arm, t (439) = 15.15, p < .001. Similarly, when the denominator was the number of expected samples, rates of negative samples were higher in the cocaine-negative than cocaine-positive arm, t (439) = 8.30, p < .001, with means (SD) of 56.9% (30.9) and 28.5% (31.5), respectively. LDA was also significantly higher, with means (SD) of 5.1 (4.2) weeks in the cocaine-negative versus 2.3 (3.5) weeks in the cocaine-positive arm, F (1,440) = 6.25, p <.001.

Post-treatment abstinence

At the 9-month follow-up, proportions of patients who self-reported abstinence in the past month and submitted negative samples were: 38.7%, 50.0%, 37.8% (positive arm: SC, $250Abs, and $560Abs conditions, respectively), 59.3%, 52.4%, and 47.2% (negative arm: SC, $250Abs, and $250Att conditions, respectively). Logistic regressions evaluated predictors of abstinence. In examining only patients who completed the follow-up (see Fig 1), clinic and baseline characteristics (Step 1) were not associated with abstinence at month 9 in either study arm. However, when Step 2 was included with treatment condition and LDA, both the step and overall model were significant in both arms. In the cocaine-positive arm, Step 2 was significant, χ2 (3) = 27.23, p < 0.001, as was the model, χ2 (8) = 31.56, p < 0.001, with 75.5% of cases correctly identified. In the cocaine-negative arm, Step 2 was also significant, χ2 (3) = 9.20, p < 0.05, along with the model, χ2 (8) = 17.77, p < 0.05, and 60.4% of cases were correctly identified. The only significant predictor in the cocaine-positive arm was LDA, with each additional week of abstinence associated with a 49% increased probability of abstinence at month 9, Beta (B) (Standard Error (SE)) = 0.39 (0.10), Wald = 16.80, p <.001; odds ratio (OR) = 1.49, 95% confidence interval (CI) =1.23-1.80). In the cocaine-negative arm, LDA was also a significant predictor, with each week of abstinence during treatment associated with an 8% increased probability of abstinence at month 9 (B(SE) = 0.08 (0.03), Wald = 6.12, p < .02; OR = 1.08, 95%CI = 1.02-1.15). In this study arm, clinic was also a significant predictor of month 9 abstinence, with clinic D having a significantly lower portion of patients abstinent (B(SE) = -1.12 (0.38), Wald = 8.79, p<.01; OR = 0.33, 95%CI = 0.16-0.69).

Results were similar when patients who failed to complete the 9-month follow-up were included in the analysis as relapsed. Step 1 was not significant in predicting abstinence, but Step 2 was: χ2 (3) = 28.95, p < 0.001 for patients in the cocaine-positive arm, and χ2 (3) = 17.91, p < 0.001 for patients in the cocaine-negative arm. Overall models were also significant χ2 (8) = 33.45 and 23.96, ps <0.001 for the two respective study arms, with 77.1% and 62.2% of cases correctly identified. LDA was the only significant predictor of abstinence in the cocaine-negative (B(SE) = 0.40 (0.09), Wald = 18.66, p <.001; OR = 1.50, 95%CI = 1.25-1.80) and cocaine-positive arm (B(SE) = 0.11 (0.03), Wald = 14.24, p< .001; OR = 1.12, 95%CI = 1.06-1.18).

Reinforcement earned and adverse events

The mean (SD) draws earned in the cocaine-positive arm was 34.5 (51.8) in the $250Abs condition and 51.5 (63.3) in the $560Abs condition, resulting in $65.2 (108.6) and $303.4 (355.2) in prizes in the respective conditions, F(1,73) = 14.52, p <.001. In the cocaine-negative arm, mean draws earned were 90.0 (67.3) in the $250Abs condition and 106.0 (65.9) in the $250Att condition, resulting in $159.7 (134.3) and $187.0 (145.5) in prizes, respectively, which did not differ by group, F (1,223) = 2.15, p = .14. No study-related adverse events occurred, and no patients evidenced problem gambling.

Discussion

About one quarter of cocaine-dependent patients in this study initiated study treatment with a cocaine-positive sample, and baseline toxicology results were a consistent indicator of severity of drug use problems and outcomes, including shorter durations of objectively-confirmed abstinence and lower proportions of negative samples during treatment. These results are consistent with other studies showing that positive samples at treatment entry are a proxy for more severe drug problems (Alterman et al., 1996; Alterman et al., 1997), and these patients fare poorly during standard outpatient treatment.

Cocaine-positive samples at treatment entry also result in poor outcomes during usual magnitude prize ($400) or voucher ($1000) CM (Preston et al., 1998; Silverman et al., 1999). Silverman et al. (1999) found that increasing the magnitude of vouchers available to over $3000 during a 12-week treatment period improved outcomes in cocaine-dependent methadone patients with high baseline levels of drug use. Similarly, Higgins et al. (2007) found that increasing voucher magnitudes improves outcomes in non-methadone maintained cocaine-dependent patients. This study is the first known prospective evaluation of increasing the magnitude of prize CM, and it confirmed that higher magnitude prize earnings improve durations of abstinence achieved relative to SC. Usual magnitude CM was as efficacious as higher magnitude CM in terms of enhancing the proportion of negative samples submitted when only submitted samples were analyzed, but the usual magnitude CM condition showed no significant benefit relative to SC when expected samples were included in the denominator in the analyses of proportions of negative samples. Further, only the $560Abs condition sustained longer durations of abstinence than SC. Given the robustness of LDA as a predictor of long-term abstinence in this and prior studies (Higgins, Badger, & Budney, 2000a; Higgins et al., 2000b; Petry et al., 2005a, 2006a), the $560 condition may be somewhat more effective for these more severe patients.

Nevertheless, in both CM conditions, the proportion of negative samples was low, regardless of whether or not missing samples were included in the denominator, and even in the high magnitude condition, patients achieved less than a month of abstinence on average. Greater magnitudes of reinforcement or approaches other than CM may be necessary to engender better outcomes in this population.

Among those who initiated treatment with cocaine-negative samples, CM interventions that reinforced abstinence and attendance were equally efficacious in improving durations of objectively confirmed abstinence achieved. When submitted samples were considered in the analyses, the vast majority of samples left during treatment tested negative by patients in this study arm. These data are consistent with other studies in psychosocial clinics (Petry et al., 2004; Petry et al., 2005a,c; Petry et al., 2006a), finding low rates of drug use while patients remain engaged in treatment. Although the vast majority of samples left during treatment tested negative in these patients, patients assigned to the $250Att condition submitted lower proportions of drug-negative samples than patients in other conditions when missing samples were not considered in these analyses. These findings may reflect an increase in during-treatment drug use in about an additional 11% of patients in this condition that did not reinforce abstinence, or it may represent a greater tendency of patients receiving this intervention to attend treatment after a brief lapse. Patients assigned to the $250Att condition indeed attended more study sessions and left more samples than those in any other condition. Further, when the denominator consisted of the total number of expected samples, patients in both CM conditions submitted a higher proportion of drug negative samples than those assigned to SC. Although some discrepancies in outcomes are noted depending on how missing samples are treated for the proportion abstinent data, patients in the $250Att condition sustained longer durations of objectively confirmed abstinence than those in SC, and LDA was consistently associated with abstinence at a 9 month follow-up.

Several features of the study design merit consideration in interpreting these findings. The $560Abs condition in the cocaine-positive arm reinforced initial abstinence at high magnitudes, and after one month, reinforcement levels decreased to the same level as the $250Abs condition. This $560Abs condition was successful in enhancing LDA, but other methods of increasing reinforcement magnitude may be equally or more effective (e.g., increasing magnitudes of prizes available or probabilities over the entire treatment period). Most patients in this condition did not achieve a full month of abstinence or directly experience the reduction in reinforcement.

Although $250Att enhanced attendance at study sessions in the cocaine-negative arm, it had no effect on duration of time in clinical treatment. This effect may represent more regular attendance before treatment withdrawal. It may also reflect a clinical practice related to limited availability of aftercare groups. Many patients continued attending the more flexible research sessions than continued in aftercare groups, which were held only weekly and often not covered by insurance. Programs with consistent treatment durations may find more pronounced effects of CM on attendance.

A concern about these findings is that about half the patients relapsed to substance use during the post-treatment period. Therefore, further development and evaluation of interventions (CM or otherwise) that prolong long-term abstinence are necessary.

Strengths of this study include the large overall sample size, high rates of follow-up, and implementation in four community-based clinics. These features increase generalization of the findings. In addition, this is the first study to use a variant of an adaptive design to tailor reinforcement target to initial treatment status and to reinforce attendance alone and closely monitor its effects on substance use.

Although research staff did not share sample results with clinicians, an attendance-based CM treatment that does not monitor drug use may result in greater rates of use. Nevertheless, when attendance-based CM is introduced clinically, usual regulations should apply to patients who use during treatment. These may include occasional urine testing and referrals to higher levels of care and cessation of CM treatment upon submission of repeated positive samples.

This study is of potential clinical significance in that it demonstrates the efficacy of attendance-based CM on some, but not all, outcomes. CM interventions that reinforce attendance alone have substantial advantages in terms of adoption, and community settings are already implementing such interventions (Kellogg et al., 2005; Ledgerwood et al., 2008). These data indicate that an attendance-based CM protocol is equally efficacious to one that reinforces negative samples in enhancing objectively confirmed durations of abstinence among cocaine-dependent patients who initiate treatment after having achieved a brief period of abstinence. The effects of this intervention on increasing proportions of negative samples, however, differed depending on how missing samples were considered in the analyses. More research needs to examine objectively substance use when patients are not attending treatment. If patients escalate substance use when they are reinforced for attendance alone, then entirely attendance-based CM procedures should clearly not be adopted clinically. On the other hand, if substance use is low across multiple populations (e.g., cocaine, alcohol, and/or marijuana dependent outpatients), then attendance-based CM may be well suited for the majority of patients initiating outpatient treatment programs. Moreover, attendance-based CM may be efficacious at lower reinforcement magnitudes than that applied herein as a prior study (Petry et al., 2004) shows similar efficacy of $80 and $240 abstinence-based CM conditions in patients who initiate treatment after having achieved a brief period of abstinence. Development and assessment of an even lower-cost prize procedure for reinforcing attendance in groups is underway (Alessi et al., 2007; Ledgerwood et al., 2008; Petry et al., 2001), and group-based reinforcement may produce similar benefits at substantially lower costs.

Results from this study also suggest that patients who do not attain abstinence early in treatment benefit from CM that reinforces abstinence and these patients may require larger magnitudes of reinforcement or other more intensive treatments to improve outcomes. If the costs of implementing high magnitude abstinence-based CM are considered too great, clinics may choose to administer only attendance-based CM to patients who are able to achieve a brief period of abstinence. Cost-effectiveness analyses (Olmstead, Sindelar, & Petry, 2007a,b; Sindelar, Elbel, & Petry, 2007; Sindelar, Olmstead, & Peirce, 2007) indicate that collecting and screening urine samples add substantially to implementation costs of CM, and usual magnitude prize CM is ineffective in patients who initiate treatment with positive urinalysis results (Stitzer et al., 2007). By limiting frequent urine testing to those who are most likely to benefit from abstinence-based CM and directing lower-cost attendance CM procedures to patients who primarily maintain abstinence during treatment, resources may be better allocated toward subgroups of substance abusers who are likely to benefit from forms of CM that reinforce different behaviors.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study and preparation of this report was provided by NIH Grants P50-DA09241, P30-DA023918, R01-DA016855, R01-DA13444, R01-DA018883, R01-DA021567, R01-DA022739, R01-DA024667, R01-DA027615, P60-AA03510, and M01-RR06192.

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Bruce Rounsaville, for his support, guidance, and humor.

References

- Alessi SM, Hanson T, Wieners M, Petry NM. Low-cost contingency management in community clinics: delivering incentives partially in group therapy. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15:293–300. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alterman AI, Kampman K, Boardman CR, Cacciola JS, Rutherford MJ, McKay JR, et al. A cocaine-positive baseline urine predicts outpatient treatment attrition and failure to attain initial abstinence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;46:79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alterman AI, McKay JR, Mulvaney FD, McLellan AT. Prediction of attrition from day hospital treatment in lower socioeconomic cocaine-dependent men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;40:227–233. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. text revision (DSM-IV-TR) [Google Scholar]

- Bovasso GB, Alterman AI, Cacciola JS, Cook TG. Predictive validity of the Addiction Severity Index's composite scores in the assessment of 2-year outcomes in a methadone maintenance population. Psychology of Addictive Behavior. 2001;15:171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Murphy SA, Strecher V. The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART): new methods for more potent eHealth interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32:S112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Silverman K, Chutuape MA, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Voucher-based reinforcement of opiate plus cocaine abstinence in treatment-resistant methadone patients: effects of reinforcer magnitude. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9:317–325. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:179–187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Badger GJ, Budney AJ. Initial abstinence and success in achieving longer term cocaine abstinence. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000a;8:377–386. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Foerg FE, Donham R, Badger GJ. Incentives improve outcome in outpatient behavioral treatment of cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:568–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950070060011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH, Dantona R, Donham R, Matthews M, Badger GJ. Effects of varying the monetary value of voucher-based incentives on abstinence achieved during and following treatment among cocaine-dependent outpatients. Addiction. 2007;102:271–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Wong CJ, Badger GJ, Ogden DE, Dantona RL. Contingent reinforcement increases cocaine abstinence during outpatient treatment and 1 year of follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000b;68:64–72. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg SH, Burns M, Coleman P, Stitzer M, Wale JB, Kreek MJ. Something of value: the introduction of contingency management interventions into the New York City Health and Hospital Addiction Treatment Service. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ, Kleber HD. Concurrent validity of the addiction severity index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1983;171:606–610. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198310000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood DM, Alessi SM, Hanson T, Godley MD, Petry NM. Contingency management for attendance to group substance abuse treatment administered by clinicians in community clinics. Journal of Applied Behavioral Analysis. 2008;41:517–526. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101:192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SA, Collins LM, Rush AJ. Customizing treatment to the patient: adaptive treatment strategies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:S1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead TA, Sindelar JL, Petry NM. Clinic variation in the cost-effectiveness of contingency management. American Journal on Addictions. 2007a;16:457–460. doi: 10.1080/10550490701643062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead TA, Sindelar JL, Petry NM. Cost-effectiveness of prize-based incentives for stimulant abusers in outpatient psychosocial treatment programs. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007b;87:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce JM, Petry NM, Stitzer ML, Blaine J, Kellogg S, Satterfield F, et al. Effects of lower-cost incentives on stimulant abstinence in methadone maintenance treatment: A National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:201–208. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM. Prize-based contingency management is efficacious in cocaine-abusing patients with and without recent gambling participation. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;39:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Carroll KM, Hanson T, MacKinnon S, Rounsaville B, et al. Contingency management treatments: Reinforcing abstinence versus adherence with goal-related activities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006a;74:592–601. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Hanson T, Sierra S. Randomized trial of contingent prizes versus vouchers in cocaine-using methadone patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:983–991. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Marx J, Austin M, Tardif M. Vouchers versus prizes: contingency management treatment of substance abusers in community settings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005a;73:1005–1014. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Kolodner KB, Li R, Peirce JM, Roll JM, Stitzer ML, Hamilton JA. Prize-based contingency management does not increase gambling. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006b;83:269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B, Cooney JL, Kranzler HR. Give them prizes, and they will come: contingency management for treatment of alcohol dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:250–257. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B, Finocche C. Contingency management in group treatment: a demonstration project in an HIV drop-in center. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2001;21:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B, Simcic F., Jr Prize reinforcement contingency management for cocaine dependence: integration with group therapy in a methadone clinic. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005b;73:354–359. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Peirce JM, Stitzer ML, Blaine J, Roll JM, Cohen A, et al. Effect of prize-based incentives on outcomes in stimulant abusers in outpatient psychosocial treatment programs: a national drug abuse treatment clinical trials network study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005c;62:1148–1156. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Simcic F., Jr Recent advances in the dissemination of contingency management techniques: clinical and research perspectives. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23:81–86. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Tedford J, Austin M, Nich C, Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ. Prize reinforcement contingency management for treating cocaine users: how low can we go, and with whom? Addiction. 2004;99:349–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston KL, Goldberger BA, Cone EJ. Occurrence of cocaine in urine of substance-abuse treatment patients. Journal of Analytic Toxicology. 1998;22:580–586. doi: 10.1093/jat/22.7.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, Rosnow R. Essentials of behavioral research: Methods and data analysis. 2nd. New York: McGraw Hill; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sigmon SC, Stitzer ML. Use of a low-cost incentive intervention to improve counseling attendance among methadone-maintained patients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;29:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Chutuape MA, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Voucher-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in treatment-resistant methadone patients: effects of reinforcement magnitude. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:128–138. doi: 10.1007/s002130051098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Broome KM. A national 5-year follow-up of treatment outcomes for cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:538–544. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindelar J, Elbel B, Petry NM. What do we get for our money? Cost-effectiveness of adding contingency management. Addiction. 2007;102:309–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindelar JL, Olmstead TA, Peirce JM. Cost-effectiveness of prize-based contingency management in methadone maintenance treatment programs. Addiction. 2007;102:1463–1471. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01913.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer ML, Petry N, Peirce J, Kirby K, Killeen T, Roll J, et al. Effectiveness of abstinence-based incentives: interaction with intake stimulant test results. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:805–811. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, Del Boca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. Journal of Studies on Alcoholism, Supplement. 1994;12:70–75. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TenHave TR, Coyne J, Salzer M, Katz I. Research to improve the quality of care for depression: alternatives to the simple randomized clinical trial. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2003;25:115–123. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00275-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]