Abstract

The role of circumcision in the transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) among men who have sex with men (MSM) in resource restricted regions is poorly understood. This study explored the association of circumcision with HIV seroprevalence, in conjunction with other risk factors such as marriage and sex position, for a population of MSM in India. Participants (n=387) were recruited from six drop in centers in a large city in southern India. The overall HIV prevalence in this sample was high, at 18.6%. Bivariate and multivariable analyses revealed a concentration of risk among receptive only, married, and uncircumcised MSM, with HIV prevalence in this group reaching nearly 50%. The adjusted odds of HIV infection amongst circumcised men was less than one-fifth that of uncircumcised men (adjusted odds ratio (AOR, 0.17; 95% 0.07-0.46). Within the group of receptive only MSM, infection was found to be lower amongst circumcised individuals (AOR, 0.23, 95% CI 0.09 – 0.61) in the context of circumcised MSM engaging in more UAI, having a more recent same sex encounter and less lubricant use when compared to uncircumcised men. To further explain these results, future studies should focus less on traditional epidemiologic analyses of risk that are typically conducted in these settings and more on better understanding MSM partnering patterns including formal analyses of potentially overlapping social and sexual networks.

Keywords: Circumcision, Men who have sex with men, India, HIV prevention, Sexual behavior

Introduction

A number of studies have examined the association of circumcision and HIV amongst men who have sex with men (MSM) and have been reviewed in detail elsewhere (1, 2). The main conclusion from these studies in aggregate suggests that there is little evidence for circumcision reducing the risk of HIV acquisition amongst MSM. One study in Australia did find a lower rate HIV infection amongst circumcised insertive only MSM (3), however studies of circumcision and MSM in resource restricted settings are less conclusive, with only one study demonstrating HIV seroconverters to be marginally less likely to be circumcised (4) and another demonstrating decreased likelihood of HIV infection amongst insertive partners in South Africa (5).

It is plausible that sex position in conjunction with circumcision is likely to play a role in HIV acquisition amongst MSM, with circumcised insertive only individuals being at reduced risk for acquisition (3). However in nearly all studies in Western settings, there remains little evidence for the benefits of circumcision (6), even with stratification for sex position and a particular focus on insertive only sex participants (7-10). Studies also suggest that the sexual behaviors and practices of MSM vary considerably across and even within cultures, resulting in diverse risk patterns (11). In several Western settings it has been shown that only a minority of MSM exclusively or predominantly practice a given sex position; rather the majority shift modality depending upon setting and partner contexts (12), and can be characterized as dual or versatile [3, 10]. In other settings, MSM are differentiated and identified based on their role in sexual relations with other men e.g., distinctions such as activo vs. passivo in Latin America (13) or kothi vs. panthi in India (14). MSM in these contexts generally follow normative sex positioning roles with insertive partners less stigmatized or viewed as normal. While there is some flexibility in this structure and some MSM are both insertive and receptive, e.g., Double-Deckers in India, indigenous MSM identify themselves and others according to this schema and there is more widespread adherence to exclusively one sex position. Therefore greater attention is required to understand these patterns of social and behavioral conducts in these settings, and their role in HIV transmission given forthcoming novel biologic HIV prevention interventions (15), many of which are likely to be promoted within MSM populations broadly.

In India, MSM represent a heterogeneous group at high risk for HIV infection (16). In addition to a distinct gay identity, other identities based upon sex position preference exist (11) the most prominent of which are receptive male partners (kothi), insertive male partners (panthi) and both receptive and insertive partners with men (double deckers). These distinct identities which include considerable segments of the MSM community could help further understandings of the role of circumcision in HIV acquisition. The possible protective effect of circumcision could be of additional interest given high rates of marriage (to women) and bisexuality in this setting (16, 17), and the potential for bisexual MSM to be a bridge population for transmission of HIV outside of MSM networks. In one study in India, the role of circumcision as protective against HIV has been determined for men attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic (18), however, the majority of this group was exclusively heterosexual. Recent reports (17, 19) of subgroups of MSM such as married MSM being at increased risk for HIV infection have not accounted for important behavioral characteristics of these MSM (e.g., sex position preference) or biologic characteristic (e.g., circumcision status), both of which can have important roles in HIV transmission dynamics. The present study was conducted to determine the relationship between circumcision, HIV status and other social and behavioral modifiers of this potential relationship. MSM were recruited within Andhra Pradesh, a state with the highest numbers of HIV infected in India, and in the city of Hyderabad, which is 41% Muslim and holds one of the most concentrated Muslim populations in the country (20).

Methods

Participants and setting

The study was conducted at six MSM drop-in centers managed by a local community based organization (CBO), Mithrudu (“Friend”), between August 2008 and June of 2009. Drop-in centers are small private apartments/office spaces where MSM CBOs gather and provide social and clinical services to the community. MSM between the ages of 18-49, who were fluent Hindi or Telugu speakers, identified as men, and reported that they had anal intercourse with another man in the past 12 months were eligible for participation. A convenience sample of clients presenting at the drop in centers was generated from all individuals entering the drop-in center and who were approached by an outreach worker, and assessed for eligibility as candidate participants. One trained research assistant subsequently collected written informed consent, performed the interview, and conducted the HIV VCT procedures on all eligible and consenting study participants. The protocol and procedures were approved by the appropriate ethics committees in India and the United States. Study participants were offered HIV test results as well as referral for additional services if appropriate.

Data collection

Confidential interviews were administered in person by one trained research assistant with 5 years experience working with this population. Interviews were conducted to obtain social, behavioral and biologic information and other risk factors that may be associated with the occurrence of HIV in this population. Social strata information included age, education, income caste and marital status. The caste system is a social class hierarchy upheld in India, and categories used for caste were those defined by the Government of India (from highest to lowest) as Forward Caste, Backwards Caste, Scheduled Caste, and Scheduled Tribe. All references to marriage in our questionnaire and in our data referred to marriage between a man and a woman. Information relevant to this paper included recency of last intercourse with a male sex partner, sex position preference with male partners (e.g. insertive, receptive, dual), HIV testing history (e.g. date of last test, location and results), self-reported circumcision status, and unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) with last sex partner. HIV testing was conducted using standard methods and kits for detecting HIV-1/2 utilizing minimally invasive sampling strategies, and included three sequential ELISAs in accordance with National AIDS Control Organizationl guidelines (21) (First Response HIV 1-2.0, PMC Medical, India; Determine HIV 1/2, Inverness Medical, USA; Capillus HIV-1/HIV-2, Trinity, Ireland). Study participants who were found to be infected were referred to local centers with capacity for government approved CD-4 testing and/or HIV therapy.

Analysis

The primary goal of this study was to determine the association between HIV seroprevalence, circumcision, and other potential socio-behavioral risk factors in MSM. Chi-square or Fisher's exact statistics were used for bivariate analyses. For all estimates of the odds ratio, 95% confidence intervals were calculated to assess precision and statistical significance. Multiple logistic regression was conducted on HIV status using predictor variables statistically significant from bivariate analyses: participants' age, education, caste, circumcision, marriage status, sex position preference, UAI, recency of last sex with a man, lubricant use, alcohol use, and any STI symptoms. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were reported with p values less than 0.05 considered statistically significant. A backwards selection process was used to identify those variables that were the strongest independent predictors of HIV seroprevalence in the final model. STATA (version 11.0) was used for statistical analyses.

Results

Socio-demographic description of sample

A total of 387 MSM were enrolled for participation. Sociodemographic characteristics of the MSM in this sample are presented in Table 1. Overall the sample was relatively young, with a median age of 26 (range 24 – 30 years); 94.8% of the sample was 40 or younger. Less than one third (30.6%) of the MSM were married, which in large part may be due to the overall youth of the sample. Among men in their thirties 59.3% were married, while 77.8% of men in their forties were married. Only 1.8% of the unmarried sample reported being separated or divorced. The majority of men were Hindu (62.5%), almost one-third were Muslim (31.8%), and the remaining MSM were Christian (5.7%).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Men who ave Sex with Men in Hyderabad India (n=387).

| Characteristic (N) | % |

|---|---|

| Age (386) | |

| Less Than 20 years | 6.2 |

| 20-24 years | 27.2 |

| 25-29 years | 36.8 |

| More than 29 years | 29.8 |

| Education (361) | |

| Primary (< 6) | 11.6 |

| Secondary (6-10) | 56.8 |

| Higher (11-12) | 20.5 |

| College (>12) | 11.1 |

| Marital Status (386) | |

| Unmarried/Divorced | 69.4 |

| Married | 30.6 |

| Occupation (352) | |

| Begging and Sex Work | 19.0 |

| Labor | 15.9 |

| Professional | 12.5 |

| Service | 27.3 |

| Student | 11.1 |

| Transport Related | 7.7 |

| Unemployed | 6.5 |

| Monthly Income in Indian Rupees ($US) (283) | |

| < 3500 ($90) | 18.7 |

| 3500 – 4999 ($90- 125) | 31.4 |

| 5000 – 6499 ($125-165) | 32.5 |

| ≥ 6500 ($165) | 17.3 |

| Religion (387) | |

| Christian | 5.7 |

| Hindu | 62.5 |

| Muslim | 31.8 |

| Caste (387) | |

| Forward Caste | 8.8 |

| Backwards Caste | 22.2 |

| Scheduled Caste | 26.4 |

| Scheduled Tribe | 8.3 |

| Not Applicable | 34.4 |

| Circumcision (382) | |

| Uncircumcised | 63.1 |

| Circumcised | 36.9 |

Data Missing: 1 for age, 26 for education, 1 for marital status, 35 for occupation, 104 for income, 5 for circumcision. Numbers in sub- categories may not add to 100% due to some missing data.

The MSM in this sample were relatively broadly distributed across our indicators of socio-economic status, though compared to studies of MSM in wealthier countries these levels may seem low (22). Over two thirds of the sample (68.4%) completed 10 years or less of education. In regard to occupation, the rate of unemployment was only 6.5%, however one fifth of participants reported begging or sex work as their primary occupation (19.0%), while another 15.9% worked as laborers. Just over one quarter (27.3%), the largest portion of the sample, reported work in the service industry. An additional 7.7% reported transport related work, 12.5% were professionals, and just over 10% of the sample were students. About three quarters (73.1%) of the sample reported a monthly income with a mean of about 5000 INR (∼$110). About two thirds of the MSM associated with a specific caste (65.7%), with less than a tenth of the sample belonging to the highest status caste (8.8% forward caste).

One of the strengths of this sample was the mixture of circumcised and uncircumcised MSM. Almost two thirds (63.1%) of the sample was uncircumcised, and the remaining one third was circumcised. Circumcision is highly correlated with religion in India, and in our sample 99.2% of the 123 Muslim men self-reported circumcised status. This is compared to just over a quarter (27.3%) of the 22 Christians and only 5.5% of the 237 Hindu men. Five of the Hindu men did not answer the question about circumcision, and these five cases were excluded from the multivariate analyses.

Distribution of Behavior and Risk Practices

Table 2 presents the distribution of sexual behaviors and risk associated with HIV transmission, as well as HIV status and CD4+ lymphocyte counts for our sample of MSM. In India, socially recognized distinctions between MSM are made based on their role in sex with other men, which we refer to as sex position. A strong indication that these sex positions are recognized by Indian MSM is that they were specially named by participants during the interviews. Almost two thirds (64.5%) of our sample reported assuming the receptive role in sex with other men; 20.5% reported being insertive only in sex with men. An additional 15.0% of men in our sample said they took a dual role during sex with other men.

Table 2.

Behavioral Characteristics of Men who have Sex with Men in Hyderabad India (n=387).

| Characteristic (N) | % |

|---|---|

| Sex Position (386) | |

| Receptive | 64.5 |

| Dual | 15.0 |

| Insertive | 20.5 |

| Age at First Sex with Man (362) | |

| 12-14 yrs | 8.3 |

| 15-17 yrs | 48.6 |

| 18-20 yrs | 40.6 |

| Over 20 yrs | 2.5 |

| Ever Pay Money or Gift for Sex (379) | |

| No | 77.8 |

| Yes | 22.2 |

| Ever Receive Money or Gift for Sex (382) | |

| No | 34.6 |

| Yes | 65.4 |

| Last Anal Sex with man (368) | |

| 1-2 days | 15.8 |

| 3-7 days | 60.6 |

| > 7 days | 23.6 |

| Unprotected Anal Intercourse (381) | |

| Sometime/never | 50.9 |

| Always/often | 49.1 |

| Lubricant Use (359) | |

| Sometime/never | 83.6 |

| Always/often | 16.4 |

| History of Alcohol Use (369) | |

| No | 35.2 |

| Yes | 64.8 |

| Frequency of Alcohol Use (200)† | |

| Daily | 15.0 |

| 4 or more times a week | 19.5 |

| 2 to 3 times a week | 22.0 |

| 2 to 4 Times a month | 28.5 |

| Once a month | 15.0 |

| STI Diagnosed in Last 6 Months (313) | |

| No | 73.2 |

| Yes | 26.8 |

| Currently with an STI (323) | |

| No | 84.5 |

| Yes | 15.5 |

| Frequency of Cleaning Under Foreskin/Penis (230) | |

| Everyday | 47.8 |

| 2-4 times a week | 14.3 |

| Once a week | 26.1 |

| 1 or less a month | 11.7 |

| When is Foreskin/Penis Cleaned (270) | |

| After Sex | 0.7 |

| After Sex/Bathing | 14.1 |

| Bathing | 85.2 |

| HIV Status (387) | |

| Negative | 81.4 |

| Positive | 18.6 |

| CD4 Count (43)‡ | |

| <200 | 27.9 |

| 200-350 | 37.2 |

| 350-500 | 23.3 |

| >500 | 11.6 |

Data Missing: 1 for sex position, 25 for age at first sex with man, 8 for giving money/gifts for sex, 5 for receiving money/gifts for sex, 19 for last anal sex, 6 for UAI, 28 for lubricant, 18 for alcohol, 39 for alcohol frequency, 74 for STI in last 6 months, 64 for current STI, 57 for cleaning frequency, 17 for time of cleaning, 27 for CD4 count. Total for sub-categories may not add to 100% due to missing data.

Values reflective of participants with history of active alcohol use

Values reflective of HIV infected participants who followed up for CD-4 testing (n=200).

The overall HIV seroprevalence in the sample is quite high, 18.6%. Not surprisingly, the rates of sexual and other risk factors were also quite high. Overall, the MSM in our sample began having sex with men when they were relatively young – 56.9% reported first having sex with a man before they turned 18 years old and 97.5% of the men had their first homosexual experience by the age of 20. Over one fifth of the sample (22.2%) reported having given money or a gift for sex, and another 65.4% having received money or a gift in exchange for sex with another man. The frequency of sex among these MSM appears high, with over three-quarters reporting their most recent anal sex within the previous week (76.4%). Just over half of the sampled men reported UAI always or often and the other half only sometimes or never.

More than two-thirds of the sample reported alcohol consumption (64.8%). The overall percent of non-drinkers (35.2%) was similar to the percent of Muslim in the sample (32%), however 53% of the Muslim MSM reported drinking. Yet this is still a great deal lower than the 73.0% drinking rate of the Hindu MSM.

Sex Position, Circumcision, Marital Status, and HIV

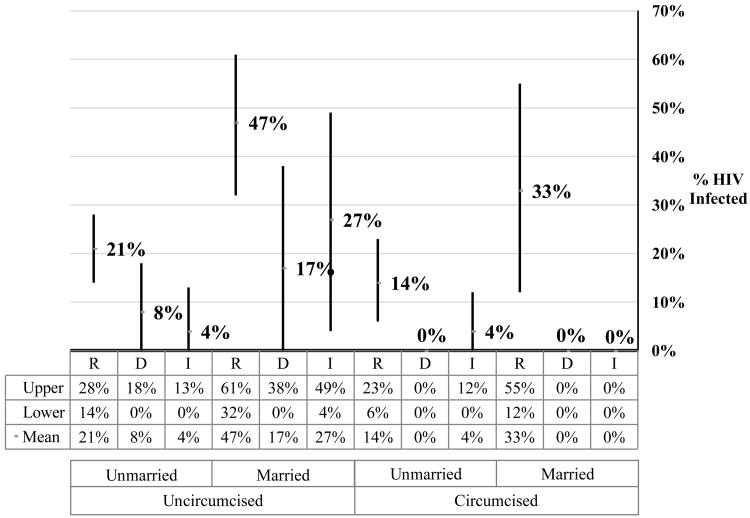

Figure 1 displays the percent HIV positive along with 95% confidence intervals for the percentage within sub-groups defined by sexual position, marital status, and circumcision for the 387 MSM in our sample. This allows one to visually compare the effect of each explanatory variable on HIV seroprevalence rate across groups defined by the other two factors. For example, looking at sex position we see that receptive MSM have the highest rates of HIV among MSM with the same marital and circumcision status. The rates for insertive and dual men are roughly comparable, and in all cases much lower than receptive men in the same marital and circumcision category. This similarity is surprising given the general understanding of risk associated with sex position. One might expect the insertive only MSM to be at a lowest risk for HIV than the dual MSM who take both the receptive and insertive role in anal sex. One anomalous case in this figure is the higher rate of HIV in married and uncircumcised insertive men compared to the comparable duals (27% vs. 17%). This may be explained by other factors such as UAI, numbers of partners, etc.

Figure 1. Representation of sexual position, circumcision status, marital status, and HIV seroprevalence amongst Indian MSM in Hyderabad (n=387)*.

*Percentages represent number of HIV infected individuals of respective sex position meeting marital status and circumcision condition.

† R – Receptive

‡ D – Dual

‖ I – Insertive

The magnitude of the confidence intervals is largely a function of the varying subgroup, sizes; the smaller the group the larger the standard error and therefore the confidence interval. Non-overlapping confidence intervals between two groups indicate a difference in their percentages that is significant at the 0.05 level. Large absolute differences found here, even those that do not achieve significance at the 0.05 level, seem worth noting as possibly important trends found in this sample.

Circumcision appears to have a general inverse relationship among individuals in comparable marital and sex position groups, such that uncircumcised MSM have a higher rate of HIV than those who are circumcised. The difference is most striking among the married MSM in each sex position. Among unmarried MSM circumcision has less of a “protective” effect, 14% vs. 21% among unmarried receptive men and 0% vs. 8% among unmarried dual men. In the case of unmarried insertive men, the rates are the same (4%).

The highest rate of HIV (47%) was found among uncircumcised, married receptive men while the rate for circumcised, married receptive men is almost 15 percentage points lower (33%). In the case of the unmarried receptive men there is also a potential protective effect of circumcision (14% vs. 21%). Even though these men take exclusively the receptive role in anal sex, which carries the greatest risk of HIV transmission, circumcision appears to provide some protection. So while the rates of HIV are highest among receptive men, there is a large difference based on marital status and more surprisingly based on circumcision. In order to explore this finding, we conducted multivariate analyses of HIV risk among the receptive MSM separately.

Factors Associated with HIV Seroprevalence

Table 3 presents results of bivariate analysis and multiple logistic regression models of HIV seroprevalence for a set of demographic, biological, and behavioral risk factors.

Table 3.

Bivariate and multiple logistic regression for factors associated with HIV infection in men who have sex with men in Hyderabad, India (n=387).*

| HIV | Bivariate | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | % | OR | 95% C.I. | OR | 95% C.I. |

| Age Category | |||||

| Less Than 20 years | 20.8 | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| 20-24 years | 12.4 | 0.54 | 0.17 – 1.69 | 0.23 | 0.05 – 0.97† |

| 25-29 years | 13.4 | 0.59 | 0.20 – 1.76 | 0.23 | 0.06 – 0.99† |

| More than 29 | 29.5 | 1.60 | 0.55 – 4.62 | 0.76 | 0.17 – 3.32 |

| Education | |||||

| Primary (< 6) | 28.6 | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| Secondary (6-10) | 19.5 | 0.61 | 0.29 – 1.29 | 1.63 | 0.52 – 5.05 |

| Higher (11-12) | 14.9 | 0.44 | 0.17 – 1.10 | 1.00 | 0.24 – 4.10 |

| College (>12) | 7.5 | 0.20 | 0.05– 0.79† | 0.86 | 0.07 – 10.09 |

| Sex Position | |||||

| Receptive | 24.9 | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| Dual | 7.6 | 0.25 | 0.10 – 0.60‡ | 0.16 | 0.03 – 0.80† |

| Insertive | 6.9 | 0.22 | 0.08 – 0.64 | 0.13 | 0.03 – 0.55‡ |

| Circumcision | |||||

| Uncircumcised | 22.8 | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| Circumcised | 11.3 | 0.43 | 0.24 – 0.79‡ | 0.17 | 0.07 – 0.46‖ |

| Marriage Status | |||||

| Divorced/Unmarried | 14.6 | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| Married | 28.0 | 2.28 | 1.35 – 3.86‡ | 2.32 | 0.90 – 5.99 |

| Last time Sex with man | |||||

| 1-2 days | 27.6 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | - | |

| 3-7 days | 20.1 | 0.66 | 0.34 – 1.29 | 0.56 | 0.19 – 1.64 |

| > 7 days | 9.2 | 0.27 | 0.11 – 0.67‡ | 0.09 | 0.02 – 0.49‡ |

| Unprotected Anal Intercourse | |||||

| Sometime/never | 9.8 | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| Always/often | 27.3 | 3.45 | 1.96 – 6.25‖ | 5.10 | 2.12 – 12.35‖ |

| Lubricant Use | |||||

| Sometime/never | 21.0 | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| Always/often | 5.1 | 0.20 | 0.06 – 0.67‡ | 0.39 | 0.08 – 1.96 |

| Alcohol Use | |||||

| No | 11.5 | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| Yes | 22.2 | 2.19 | 1.18 – 4.06† | 0.81 | 0.33 – 1.99 |

| STI Symptoms | |||||

| None | 12.1 | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.0 (ref) | - |

| Any | 24.6 | 2.36 | 1.31 – 4.23‡ | 1.60 | 0.72 – 3.57 |

Values reflective of only those participants for whom we have complete data

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Age was significantly related to HIV status, with men in their twenties having lower rates of HIV (AOR 0.23, 95% CI 0.05 – 0.97) compared to men younger than twenty. The association between education and infection was not statistically significant in the bivariate model, however there was a clear linear negative trend in the sample between these variables – the lower the level of education attained, the higher the HIV seroprevalence.

Sex position was strongly related to HIV in our sample, with seroprevalence among MSM who were exclusively receptive partners in anal sex over triple the rate found among the insertive only and dual MSM. Insertive only men had the lowest prevalence compared to receptive only men (AOR 0.13, 95% CI 0.03 – 0.55), though dual MSM were also very low (AOR 0.16, 95% CI 0.03 – 0.80).

A recent finding in studies of MSM in India is that married MSM are more likely to be HIV infected than unmarried men (17, 23), with marriage referring to opposite-sex marriage. We find a similar pattern in our sample in bivariate analysis where married men were more likely to be infected than unmarried men. This finding may be explained in part by the collinearity between age and marital status as discussed earlier, and the fact that both age and marital status are related to HIV among the MSM in our sample. When age is introduced into models with marriage neither has a significant effect on HIV, while both have a significant effect on HIV when the other variable is absent (see Table 4 below). Based on the regression results, non-circumcision and UAI were the strongest predictors of HIV infection. MSM who were circumcised were much less likely to be infected than men who were uncircumcised (AOR 0.17, 95% CI 0.07 – 0.46), while those who reported UAI always or often versus sometimes or never had much greater odds of infection (AOR 5.10, 95% CI 2.12 – 12.35).

Table 4.

Factors associated with prevalent HIV infection amongst receptive men who have sex with men in Hyderabad, India (n=249).*

| Adjusted odds of HIV infection with Initial multiple logistic regression model | Adjusted odds of HIV infection with Final multiple logistic regression model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Adjusted OR | 95% C.I. | Adjusted OR | 95% C.I. |

| Age Category | ||||

| Less Than 20 years | 1.00 (ref) | - | - | |

| 20-24 years | 0.28 | 0.06 – 1.38 | - | - |

| 25-29 years | 0.27 | 0.05 – 1.34 | - | - |

| More than 29 years | 0.82 | 0.16 – 4.32 | - | - |

| Education | ||||

| Primary (< 6) | 1.00 (ref) | - | - | |

| Secondary (6-10) | 1.45 | 0.42 – 5.03 | - | - |

| Higher (11-12) | 0.87 | 0.18 – 4.09 | - | - |

| College (>12) | 1.00 | 0.07 – 15.63 | - | - |

| Circumcision | ||||

| Uncircumcised | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| Circumcised | 0.19 | 0.07 – 0.55‡ | 0.23 | 0.09 – 0.61‡ |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Divorced/Unmarried | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| Married | 2.33 | 0.83 – 6.50 | 2.84 | 1.19 – 6.77† |

| Last time Sex with man | ||||

| 1-2 days | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| 3-7 days | 0.58 | 0.18 – 1.85 | 0.66 | 0.22 – 1.97 |

| > 7 days | 0.10 | 0.01 – 0.75† | 0.12 | 0.02 – 0.80† |

| Unprotected Anal Intercourse | ||||

| Sometimes/never | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| Always/often | 5.35 | 2.08 – 13.70‡ | 4.72 | 2.01 – 11.11‖ |

| Lubricant Use | ||||

| Sometimes/never | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | - | |

| Always/often | 0.21 | 0.03 – 1.83 | 0.19 | 0.02 – 1.58 |

| Alcohol Use | ||||

| No | 1.00 (ref) | - | - | - |

| Yes | 0.69 | 0.25 – 1.94 | - | - |

| STI Symptoms | ||||

| None | 1.00 (ref) | - | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| Any | 2.18 | 0.90 – 5.25 | 2.41 | 1.07 – 5.40† |

Values reflective of only receptive participants for whom we have complete data

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

A number of measures of HIV risk related to sexual practices were associated with HIV seroprevalence, including recency of sexual contact with a male partner. Men who reported their last anal intercourse was more than one week before the interview were significantly less likely to be infected than men who had had sex in the previous one to two days (AOR 0.09, 95% CI 0.02 – 0.49). Lubricant use, alcohol use and reporting of an STI were each statistically associated with HIV infection in bivariate analysis, but lost significance in the multivariable analysis model respectively (AOR 0.39, 95% CI 0.08 – 1.96; AOR 0.81, 95% CI 0.33 - 1.99; AOR 1.60, 95% CI 0.72 – 3.57). Interestingly, in separate models (data not shown) circumcised men were more likely to engage in UAI, (AOR 2.06, 95% CI 1.16 - 3.66) and more likely to have had sex with a man in the past 1-2 days when compared to the group in the last 3-7 days (AOR 3.42, 95% CI 1.49 - 7.87).

Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with HIV Among Receptive Only Men

Almost two-thirds of the MSM in the sample define themselves as exclusively the receptive partner in anal sex with other men. As we have seen, they have a much higher rate of HIV than the other men in our sample, 24.9% compared to 14.4% for insertive and dual MSM combined. While from a physiological and biological perspective we would not expect to find a protective effect of circumcision for MSM who take the receptive role in anal intercourse, the lower HIV rates among circumcised receptive men found in Figure 1 led us to examine the effect of circumcision along with other risk factors for HIV among the receptive men in our sample.

Table 4 presents two logistic regression models for HIV status of the receptive men for whom we have complete data. The first model includes socio-demographic and sexual practice variables that were associated with HIV status in bivariate analyses, including age, marital status, circumcision, sexual behavior (recency of sex, UAI, use of lubricants, STI symptoms) and alcohol use. Education was also included in this model although it was not significant at the 0.05 level. Religion was not included because of its high collinearity with circumcision. In this model, circumcision, UAI, and recency of sex had a statistically significant association with HIV seroprevalence. A backwards selection process was then used to identify those variables that were the strongest independent predictors of HIV seroprevalence, which were then used to produce the final model. This led to the exclusion of age, education and alcohol use.

In the final model, all variables were significant at the 0.05 level except lubricant use and education. Following the pattern seen in men across sex position, both circumcision and UAI were significant indicators of HIV infection. The odds of HIV seroprevalence among circumcised men was slightly less than one quarter that for uncircumcised men after controlling for all other variables in the model (AOR 0.23, 95% CI = 0.09 – 0.61). Receptive MSM who did not report sex with a man in the previous week were less likely to be HIV infected compared to receptive MSM who reported sex within the previous two days (AOR 0.12; 95% CI = 0.02 – 0.80). Receptive MSM who reported UAI often or always also had much higher HIV seroprevalence rates when compared to MSM who practiced UAI sometimes or never (AOR 4.72; 95% CI = 2.01 – 11.11) in the final model. Both marital status and previously having an STI were associated with higher rates of HIV infection; married receptive men had nearly three times the adjusted odds of infection as their unmarried counterparts (AOR 2.84, 95% CI = 1.19 – 6.77), while MSM reporting STI symptoms were two and a half times more likely to also have HIV (AOR 2.41, 95% CI = 1.07 – 5.40).

Discussion

In this study of 387 Indian MSM with18% HIV seroprevalence, male circumcision was strongly associated with decreased HIV infection amongst study participants overall, and surprisingly this trend endured within the receptive only MSM. Additionally, there was a complex relationship between sex position, marital status and circumcision status, with marital status associated with greater rates of HIV infection in some sub-populations including receptive only MSM. Unlike most other studies of MSM and circumcision, our sample was drawn from a population with strong sex position identification, and only 15% of the sample reporting a dual (or versatile) sex position. The group of MSM was relatively evenly split by circumcision status, with 37% of the sample being circumcised. How are we to interpret the relationship between circumcision status and HIV seroprevalence amongst MSM in the sample, particularly amongst the receptive only sub-sample?

Evidence for the protective role of circumcision against HIV acquisition amongst heterosexual men (24-26) propels questions of whether this protective effect is also possible for MSM. Studies of circumcision as protective against HIV acquisition amongst MSM has yielded mixed results, with no evidence of a relationship in most Western settings (6, 27), and varied findings amongst insertive only MSM in one Western setting (3). However in resource restricted settings, some studies have suggested that circumcision has some protective effect (4, 5). While there are also trends towards a protective effect of circumcision amongst insertive only and versatile MSM in our data, the sample was not large enough for model convergence, given lower rates of insertive only partners and rates of HIV seroprevalence. What is striking from our data is the previously unreported finding of lower HIV seroprevalence amongst circumcised receptive only MSM.

It is hard to imagine a physiological or biological mechanism which would explain circumcision's observed protective effect against HIV in receptive MSM. Certainly, variation in behavior or other sociodemographics could explain these findings, for example alcohol use was more common amongst uncircumcised men. However our analyses demonstrated that behavior associated with higher risk of HIV infection (e.g., UAI, recency of sex) was more common amongst circumcised men. This increased risky sex behavior amongst Indian circumcised men has also been described in a recent large population based study (28). This suggests that our findings, as well as other findings of an association between circumcision and HIV status (29), might be even larger if sex behavior between circumcised and uncircumcised men in India was similar.

A potential explanation could be one of the most common patterns of interaction found in social and sexual networks – homophily – which accounts for the selection of network partners who share similar characteristics (30). This may provide an explanation for the lower rates of HIV among circumcised receptive only MSM, a phenomenon also postulated as explaining higher seroprevalence rates of HIV among African American MSM (10). The selection by receptive men of sexual partners who are also circumcised, and who therefore may have lower rates of HIV than sexually active uncircumcised men, may result in a lower risk of being exposed to and becoming infected with HIV. In the present study, there were no data to directly measure partner characteristics and the extent of homophily in selection of partners. However this social phenomena is widespread and evident in sexual networks of MSM in other settings [29, 30]. The significant effect of circumcision on HIV status among receptive MSM found in the multiple logistic regression models even when controlling for other variables such as marital status, recency of sex, UAI, frequency of use of lubricants, alcohol use and STI symptoms, suggests the importance of further research specifically focused on the effects of social networks, with particular attention paid to the social characteristics of sex partners.

Homophily based on circumcision may or may not operate directly on the basis of a preference for physical characteristics, including characteristic appearance of the genitals. In our sample, circumcision is highly correlated with religion. Receptive partners who are Muslim may be more likely to select their sexual partners from among insertive and versatile MSM who are also Muslim (or vice-versa). Finally, sex behavior can vary based upon circumcision status. In a landmark sex survey in the United States, masturbation was found to be more common amongst circumcised heterosexual men, although this difference varied across race and ethnic categories (31). In some settings masturbation has been posited as a potential HIV prevention strategy found to be associated with lower reported high-risk behaviors [33, 34], and future research could explore this and other sexual behaviors (e.g. oral sex) as they relate to circumcision status.

As previously suggested, dramatic differences in alcohol use between Muslim and Hindu MSM, with Hindu MSM (who are much less likely to be circumcised) reporting higher rates of alcohol use in the previous six months, could potentially explain our finding. Other sexual partnering and positioning patterns could also explain differences in circumcision status, including higher rates of Muslims taking only an insertive role. Most observational studies of circumcision and HIV serostatus suggest that any findings may be due to residual confounding of unmeasured factors (32). However many of these factors were controlled for in our models, with no significant change to the point estimate of the protective effect of circumcision in the final model. Other potential explanations for our finding include misclassification of receptive MSM and thus inclusion of insertive or dual men in this category, as this data was gathered by self-report. However, this is unlikely given the strong sex identity in this setting (11) and traditionally much lower rates of versatile positioning in this state than in western settings (1, 16). While there are some examples of anal sex between traditionally receptive partners (33), this evidence is mostly anecdotal being limited to more Western settings within India, and has not been systematically analyzed.

In sum, we found a significant inverse association of circumcision with HIV seropositivity among MSM, as well as the subcategory of receptive only MSM, when we control for other factors associated with HIV status. Biologic or physiologic mechanisms of the index participant are unlikely to explain this effect. On the other hand, homophily, or the selection of network partners who share similar characteristics, may provide an explanation for the lower rates of HIV among receptive only MSM. The selection by circumcised receptive men of sexual partners who are also circumcised, and who have lower rates of HIV than active uncircumcised men, may produce a lower risk of being exposed to and becoming infected with HIV. These findings suggest a potential need for disaggregating HIV prevention efforts towards those MSM most at risk for infection in India, acknowledging that circumcision as a prevention intervention may be difficult to implement in this setting (34). Additionally, further research is needed to more thoroughly describe MSM social networks, specifically pertaining to the social characteristics of sexual partners. Our finding that biological circumcision status operates in conjunction with other important social structural factors to influence risk of HIV infection underscores the importance of social and sexual network analyses in this context.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the study participants for their time and contribution to the study design. We would like to thank Mithrudu for their collaboration on this project and Dr. Rajender for treating study participants who were in need.

This study was supported in part by the American Foundation for AIDS Research; Dr. Schneider was supported by the National Center for Research Resources KL2RR025000, National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Millett GA, Flores SA, Marks G, Reed JB, Herbst JH. Circumcision status and risk of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008 Oct 8;300(14):1674–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Templeton DJ, Millett GA, Grulich AE. Male circumcision to reduce the risk of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010 Feb;23(1):45–52. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328334e54d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Templeton DJ, Jin F, Mao L, Prestage GP, Donovan B, Imrie J, et al. Circumcision and risk of HIV infection in Australian homosexual men. AIDS. 2009 Nov 13;23(17):2347–51. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833202b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanchez J, Lama JR, Peinado J, Paredes A, Lucchetti A, Russell K, et al. High HIV and ulcerative sexually transmitted infection incidence estimates among men who have sex with men in Peru: awaiting for an effective preventive intervention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009 May 1;51(1):S47–51. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a2671d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lane T, Raymond HF, Dladla S, Rasethe J, Struthers H, McFarland W, et al. High HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Soweto, South Africa: results from the Soweto Men's Study. 2009. AIDS Behav. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9598-y. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jozkowski K, Rosenberger JG, Schick V, Herbenick D, Novak DS, Reece M. Relations between circumcision status, sexually transmitted infection history, and HIV serostatus among a national sample of men who have sex with men in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010 Aug;24(8):465–70. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDaid LM, Weiss HA, Hart GJ. Circumcision among men who have sex with men in Scotland: limited potential for HIV prevention. Sex Transm Infect. 2010 Jun 30; doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.042895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gust DA, Wiegand RE, Kretsinger K, Sansom S, Kilmarx PH, Bartholow BN, et al. Circumcision status and HIV infection among MSM: reanalysis of a Phase III HIV vaccine clinical trial. AIDS. 2010 May 15;24(8):1135–43. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328337b8bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jameson DR, Celum CL, Manhart L, Menza TW, Golden MR. The association between lack of circumcision and HIV, HSV-2, and other sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2010 Mar;37(3):147–52. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181bd0ff0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millett GA, Ding H, Lauby J, Flores S, Stueve A, Bingham T, et al. Circumcision status and HIV infection among Black and Latino men who have sex with men in 3 US cities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007 Dec 15;46(5):643–50. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815b834d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asthana S, Oostvogels R. The social construction of male ‘homosexuality’ in India: implications for HIV transmission and prevention. Soc Sci Med. 2001 Mar;52(5):707–21. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coxon A. Diaries and sexual behaviour: the use of sexual diaries as method and substance in researching gay men's response to HIV/AIDS. In: Boulton M, editor. Challenge and Innovation: Methodological Advances in Social Research on HIV/AIDS. London: Taylor and Francis; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen L, Almaguer T. Chicano men: a cartography of homosexual identity and behavior. In: Abelove H, Barale MA, Halperin DM, editors. The lesbian and gay studies reader. New York: Routledge; 1993. pp. 255–73. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan S. Culture, sexualities, and identities: men who have sex with men in India. J Homosex. 2001;40(3-4):99–115. doi: 10.1300/J082v40n03_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider JA. Novel HIV prevention strategies: The case for Andhra Pradesh. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2008 Jan-Mar;26(1):1–4. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.38849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dandona L, Dandona R, Gutierrez JP, Kumar GA, McPherson S, Bertozzi SM. Sex behaviour of men who have sex with men and risk of HIV in Andhra Pradesh, India. AIDS. 2005 Mar 24;19(6):611–9. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000163938.01188.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumta S, Lurie M, Weitzen S, Jerajani H, Gogate A, Row-kavi A, et al. Bisexuality, sexual risk taking, and HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men accessing voluntary counseling and testing services in Mumbai, India. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Feb 1;53(2):227–33. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c354d8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reynolds SJ, Shepherd ME, Risbud AR, Gangakhedkar RR, Brookmeyer RS, Divekar AD, et al. Male circumcision and risk of HIV-1 and other sexually transmitted infections in India. Lancet. 2004 Mar 27;363(9414):1039–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15840-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solomon SS, Srikrishnan AK, Sifakis F, Mehta SH, Vasudevan CK, Balakrishnan P, et al. The Emerging HIV Epidemic among Men Who have Sex with Men in Tamil Nadu, India: Geographic Diffusion and Bisexual Concurrency. AIDS and Behavior. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9711-2. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.2001 CoI; Affairs MoH. Basic Data Sheet: District Hyderabad (05), Andhra Pradesh (28) Government of India; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guidlines for HIV Testing. New Delhi: Government of India; 2007. Mar, p. 157. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laumann EO. The social organization of sexuality: sexual practices in the United States. Pbk. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solomon SS, Srikrishnan AK, Sifakis F, Mehta SH, Vasudevan CK, Balakrishnan P, et al. The emerging HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men in Tamil Nadu, India: geographic diffusion and bisexual concurrency. AIDS Behav. 2010 Oct;14(5):1001–10. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9711-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, Agot K, Maclean I, Krieger JN, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007 Feb 24;369(9562):643–56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med. 2005 Nov;2(11):e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S, Nalugoda F, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007 Feb 24;369(9562):657–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez J, Sal YRVG, Hughes JP, Baeten JM, Fuchs J, Buchbinder SP, et al. Male circumcision and risk of HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2010 Nov 19; [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider JA, Lakshmi V, Dandona R, Kumar GA, Sudha T, Dandona L. Population-based seroprevalence of HSV-2 and syphilis in Andhra Pradesh state of India. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dandona L, Dandona R, Kumar GA, Reddy GB, Ameer MA, Ahmed GM, et al. Risk factors associated with HIV in a population-based study in Andhra Pradesh state of India. Int J Epidemiol. 2008 Dec;37(6):1274–86. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wasserman S, Faust K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. First. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laumann EO, Masi CM, Zuckerman EW. Circumcision in the United States. Prevalence, prophylactic effects, and sexual practice. JAMA. 1997 Apr 2;277(13):1052–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westercamp N, Bailey RC. Acceptability of male circumcision for prevention of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. AIDS Behav. 2007 May;11(3):341–55. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9169-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lorway R, Shaw SY, Hwang SD, Reza-Paul S, Pasha A, Wylie JL, et al. From individuals to complex systems: exploring the sexual networks of men who have sex with men in three cities of Karnataka, India. Sex Transm Infect. 2010 Dec;86(3):iii70–8. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.044909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider JA, Dandona R, Pasupneti S, Lakshmi V, Liao C, Yeldandi V, et al. Initial commitment to pre-exposure prophylaxis and circumcision for HIV prevention amongst Indian truck drivers. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]