Abstract

A new chemical dual-functional reducing agent, thiophene, was used to produce high-quality reduced graphene oxide (rGO) as a result of a chemical reduction of graphene oxide (GO) and the healing of rGO. Thiophene reduced GO by donation of electrons with acceptance of oxygen while it was converted into an intermediate oxidised polymerised thiophene that was eventually transformed into polyhydrocarbon by loss of sulphur atoms. Surprisingly, the polyhydrocarbon template helped to produce good-quality rGOC (chemically reduced) and high-quality rGOCT after thermal treatment. The resulting rGOCT nanosheets did not contain any nitrogen or sulphur impurities, were highly deoxygenated and showed a healing effect. Thus the electrical properties of the as-prepared rGOCT were superior to those of conventional hydrazine-produced rGO that require harsh reaction conditions. Our novel dual reduction and healing method with thiophene could potentially save energy and facilitate the commercial mass production of high-quality graphene.

Graphene has attracted great interest because of its unique physical properties1 arising from its rigid two-dimensional (2D) structure, and its potential applications in nanoelectronics2, energy storage materials3, polymer composite materials4 and sensing5. Mechanical exfoliation is one of the successful approaches that have been developed for the preparation of high-quality graphene sheets suitable for fundamental studies, but large-scale production of such pure graphene sheets remains unfeasible. Instead, chemical graphitisation from graphene oxide (GO) to reduced graphene oxide (rGO) is generally used for mass production of graphene6,7,8,9,10. Numerous reducing chemicals such as hydrazine11, NaBH412, hydriodic acid (HI)13, NaOH14, ascorbic acid15 and glucose16 have been used to convert GO to rGO. However, all of these reducing agents produce imperfect rGOs containing a high level of defects or disorders. Recently, Amarnath et al. introduced a pyrrole as a new chemical reducing agent in this process, but the C/O ratio showed that GO was not fully reduced and the resulting rGO contained high nitrogen contamination emanating from the nitrogen source17. Kaminska et al. also introduced reduction and functionalization of graphene oxide using tetrathiafulvalene18. Despite the urgent need for production of a defect-free rGO, there have not been any reports of chemical healing of the defects of heteroatom-free rGO in the reduction process of GO to rGO. In addition, the development of novel reduction methods that are environmentally friendly, mild, and cost effective ways remains a challenge for mass production of high-quality rGOs by chemical healing.

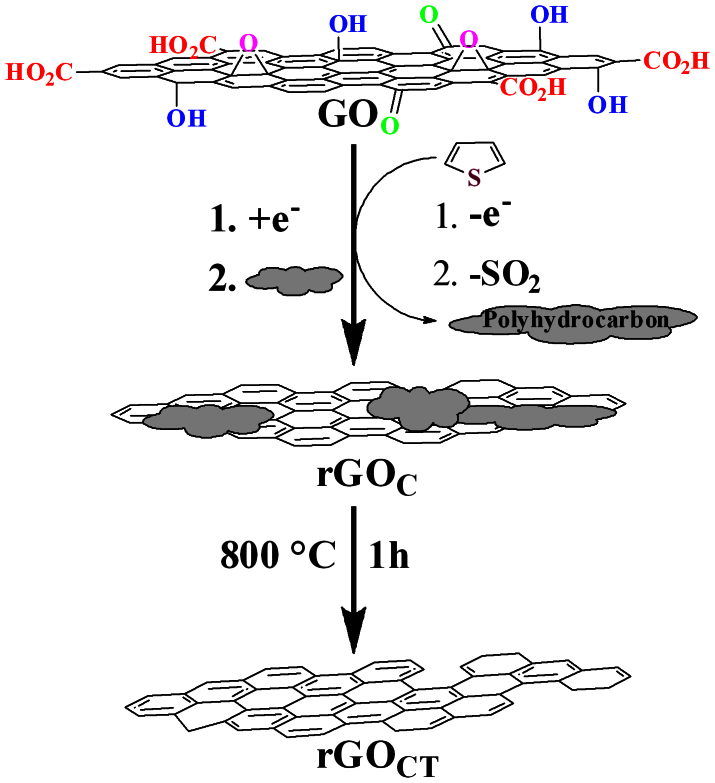

In this study, we introduce a new dual-functional reducing agent, thiophene (T) which has lower reactivity than pyrrole17 and produces high-quality, heteroatom-free rGOs by chemical healing reduction of GO. Thiophene can be used to reduce as-prepared GO by dual-functional electron donation and oxygen consumption. It is also well known that by applying a potential across a solution of thiophene, it can be polymerised, leading to its use as an oxidant of thiophene or a cross-coupling catalyst19. GO itself is also known to have oxidising capacity20. Thus we hypothesized that the mild reducing agent, thiophene could be used for effective mass production of GO to rGO by becoming an oxidised polythiophene sulfoxide or sulfone through release of electrons and uptake of oxygen. Finally, a π-conjugated polyhydrocarbon could be obtained by easy removal of the sulphur dioxide (-SO2) group of the oxidised polythiophene sulfoxide or sulfone. It is likely that the reduction and healing mechanism involves donation of electrons from thiophene monomers to reduce GO to rGO during their polymerisation into the oxidised form (i.e. thiophene sulfoxide and sulfone)21,22. The resulting polyhydrocarbon intermediate can be used as a template to heal rGO, thus providing high-quality rGO (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic diagram for the formation of rGOC and rGOCT.

rGOC was prepared by chemical reduction of as-made GO with thiophene whereas rGOCT was prepared by chemical reduction followed by thermal treatment.

Results

Preparation and characterization of healed rGO

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), powder X-ray diffraction (XRD), Raman spectroscopy, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) were employed for characterization of rGO. Thiophene was reacted with GO at 80°C for 24 h to produce high-quality rGO. In the reaction mixture, GO gained electrons to produce rGO by the formation of polymerised and oxidised thiophene. The resulting polyhydrocarbons obtained from the elimination of sulphur dioxide23 could be physically absorbed onto as-made rGO by π–π interactions17. This in-situ healing reduction process resulted in good-quality chemically reduced graphene oxide (rGOC) without any sulphur contamination compared to normal hydrazine-produced rGO which is contaminated with nitrogen and has a reduced mass. After completion of the procedure, we could not detect any thiophene in the reaction mixture by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). To demonstrate that thiophene donated electrons to GO to produce rGO, we carried out a control experiment by incubating dibenzothiophene with GO. No reaction took place and GO was not reduced. NMR after 24 h revealed unchanged dibenzothiophene with both sides of the thiophene remaining blocked by benzene rings as they were before the reaction (Figure S15 and S16). Dibenzothiophene could unable to reduce GO to rGO. This control experimental thus strongly supported our hypothesis for the reaction mechanism. Elimination of SO2 from the oxidised polythiophene was confirmed by detection of released SO2 gas (see Supplementary Information, video and Figure S8 and S9)24. To confirm the release of SO2 gas and to understand the detailed reaction pathway, we used different amounts of thiophene (0.2, 1, 2 and 5 mL) with the same amount of GO solution. We found that 2 mL of thiophene was most effective to produce high-quality rGO. To further improve the quality, we carried out thermal treatment at 800°C for 1 h. With thermal treatment, the as-prepared chemically reduced rGOC was converted to thermally-reduced graphene oxide (rGOCT) when 2 or 5 mL of thiophene had been used. We observed that after thermal treatment, the as-prepared rGOCT was highly reduced and healed in comparison to rGON2H4 produced by hydrazine.

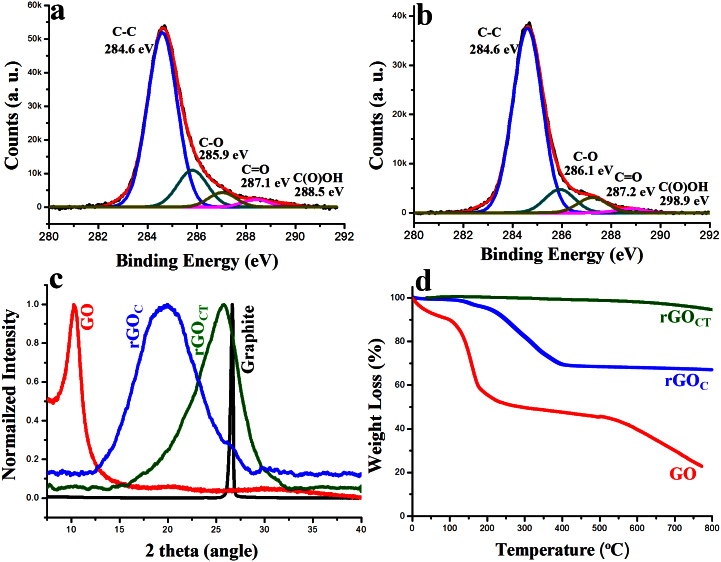

We used XPS to analyse GO and rGO produced by thiophene reduction. The high-resolution C1s XPS spectrum of the GO sheets showed a sharp peak at 284.6 eV that corresponded to C-C bonds of carbon atoms in a conjugated honey-comb lattice. Peaks at 286.7, 288.4 and 290.1 eV could be attributed to different C-O bonding configurations due to the harsh oxidation and destruction of the sp2 atomic structure of graphite (Figure S1)25. After reduction with thiophene, the intensities of all of the related oxygen peaks were sharply decreased in the rGOC sample compared to GO, indicating that the delocalized π conjugation was restored in our rGOC sample (Figure 2 a)11. Based on the XPS analyses, the as-prepared GO had a very high oxygen atomic percentage (C/O = 2). In contrast, the C/O ratio of the rGOC produced by thiophene reduction was 10.9 (Figure 2a). The C/O ratio of the as-prepared rGOCT was 16.8 (Figure 2b). We concluded that the rGO from our process contained far less oxygen, confirming its high quality. The atomic composition of all samples was analysed by XPS. We did not detect any sulphur and nitrogen in GO and rGOs, confirming that despite the use of thiophene to reduce GO, the as-prepared rGOs were not contaminated by sulphur (Figure S2). We also determined the C/O ratios of rGOs produced with different amounts of thiophene (Supplementary Information, Table S1).

Figure 2. Characteristic XPS, XRD and TGA data.

(a) High-resolution C1s spectra of rGOC. (b) High-resolution C1s spectra of as-prepared rGOCT by thiophene. (c) Powder XRD pattern of GO (red), rGOC (blue), rGOCT (green) and graphite (black). (d) TGA plots of GO (red) and rGOC (blue) and rGOCT (green). rGO had better thermal stability than GO.

The interlayer distances of as-prepared GO and rGO were confirmed by XRD. The 2θ peak of graphite powder was at 26.71°, indicating that the interlayer distance was 3.34 Å (Figure S3). The as-prepared GO showed a 2θ peak at 10.27°, indicating that the graphite was fully oxidised into GO with an interlayer distance of 8.60 Å (Figure 2c). The XRD pattern of the as-prepared rGOC showed a typical broad peak of 2θ peak with the polyhydrocarbon template at 20.1°, indicating that the interlayer distance was 4.4 Å (Figure 2c). The shift of the XRD pattern of GO (10.27°) to rGOC powder 2θ peak (20.1°) suggested that the rGOC was reduced well. The interlayer distance of rGOC was 4.4 Å, which was larger than that of graphite powder (3.34 Å) and a little broader than control rGON2H4 (Figure S3). These differences were attributed to the well-ordered 2D structure of the rGO sheets within the polyhydrocarbon template. After thermal treatment followed by chemical reduction, the as-prepared rGOCT powder 2θ peak shifted from 20.1° to 25.6° suggesting that rGO was fully reduced. The interlayer distance was 3.5 Å, which means that there was no polyhydrocarbon template in between the two rGO layers. The same results were obtained when 5 mL thiophene was used (Figure S4). Our XRD data for increasing amounts of thiophene (0.2, 1 and 2 mL) showed that the conversion of GO to rGO occurred gradually (Figure S5).

The quality of as-prepared rGO was assessed by TGA. TGA plots of GO (red) and rGO (blue and green) are shown in Figure 2d. In the GO sample, the major weight loss occurred between 100 and 200°C, indicating the release of CO, CO2 and steam from the most labile functional groups during pyrolysis26. At temperatures below 800°C, the total weight loss was about 77%. In contrast, the rGOC (blue) sample showed higher thermal stability than GO. The major weight loss was ~26% at temperatures near 300°C and the total weight loss was ~30% at 800°C. This major loss of mass could be attributed to the presence of a high amount of polyhydrocarbon on the as-prepared rGOC, whereas after thermal treatment followed by chemical reduction, total weight loss of the as-prepared rGOCT (green) was only 6%. This minor mass-loss was attributed to the absence of most oxygen functional groups.

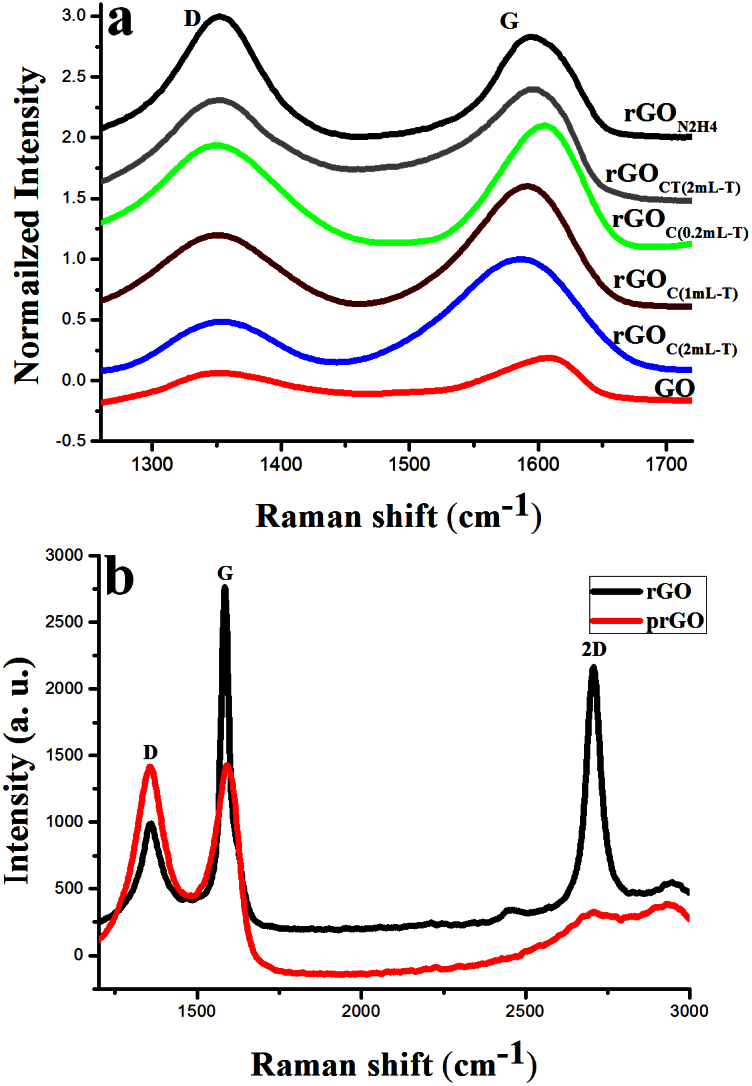

Raman spectroscopy is the most direct and non-destructive technique to characterize the structure and quality of carbon materials27,28, and in particular to investigate the defects and ordered and disordered structure of graphene. Raman spectra were collected from the as-prepared samples at an excitation wavelength of 514 nm under ambient conditions by dropping DMF dispersions on a silicon (Si) substrate. For comparison, we also collected the spectra of GO and rGO obtained from reduction of GO using thiophene under the same conditions. The Raman spectra of as-prepared GO exhibited two remarkable peaks at about 1352 and 1605 cm−1, corresponding to the well-defined D and G bands, respectively (Figure 3a). The G band is related to the E2g-vibration mode of sp2 carbon and domains can be used to explain the degree of graphitization, whereas the D band is associated with structural defects and partially disordered structures of the sp2 domains27. After thiophene reduction, the as-prepared rGOC sample had a G peak at 1585 cm−1 and D peak at 1354 cm−1. The increased ID/IG ratio of rGO after chemical reduction has been commonly reported in the literature11. In our study, the ID/IG ratio of the as-prepared rGO exhibited a significant decrease in comparison to the previously reported rGO. In the case of GO, the ID/IG ratio was 0.91 and after thiophene reduction, the as-prepared rGOC sample was 0.41, compared to the ratio of the control rGON2H4 sample of 1.2 (Supplementary Information, Table S2). We concluded that production of rGO from GO by reduction with thiophene had a healing effect29 in the presence of the resultant poly-hydrocarbon template in comparison to the control rGON2H4. When we used 0.2, 1 and 5 ml of thiophene, the corresponding ID/IG ratio of the as-prepared rGOC was 0.81, 0.65 and 0.43, respectively (Figure 3a). The ID/IG ratio of the as-prepared rGOC was almost the same for 2 mL and 5 mL thiophene (Figure 3a, S6 and S7). In both cases, after the thermal treatment followed by chemical reduction, the ratio increased, up to 0.85 and 0.83 respectively, indicating that the healing effect was still present after harsh thermal treatment30 in comparison with the control rGON2H4 produced by hydrazine. Furthermore, the intensity of the 2D peak at ~2693 cm−1 and S3 peak at ~2938 cm−1 increased for rGOC and rGOCT, showing better graphitisation and no charge transfer due to the absence of impurities (Figure S6)31. To more clearly observe this healing effect, we carried out the thiophene treatment with partial rGO (prGO) and control rGON2H4. The sample produced by thiophene treatment of prGO showed a large healing effect with a sharply increased 2D peak (Figure 3b), whereas the sample produced by thiophene treatment of rGON2H4 showed no healing effect, thus confirming our assumption. In the case of prGO, the C/O ratio was ~4.3. Thus prGO could still be reduced by the donating electron of thiophene due to the presence of abundant oxygen groups, demonstrating our assumption of the healing effect of product. In contrast, rGON2H4 had a C/O ratio of ~14 and it could not undergo effective further reduction by the donated electron of thiophene. Thus thiophene could not be polymerised to produce a polyhydrocarbon and a healing effect. AFM images of the as-prepared GO (Figure S12) showed that the average thickness of the layers was ~1 nm, indicating the formation of single-layered GO16. The average thickness of as-prepared rGOC was ~2.3 nm, which indicated the formation of polyhydrocarbon attached to rGO layers (Figure S10), whereas the average thickness of rGOCT was ~1.2 nm (Figure S11). High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) studies were also carried out for rGO sheets. HRTEM images of rGOC showed 3–5 layers of crystalline structure due to a ring-shaped pattern consisting of many diffraction spots for each order of diffraction (Figure S13a). In contrast, the HRTEM image of the rGOCT sheet (Figure S13b) was a single layer, as expected, indicating that the rGOCT sheet reduced from exfoliated GO was indeed monolayer rGOCT (Figure S13b). The insert of Figure S13b shows a selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern of rGOCT, clearly demonstrating the crystalline structure of rGO. The diffraction pattern images showed that the rGOs had been restored to the hexagonal graphene framework. Furthermore, the as-prepared rGOC and rGOCT pellets (33 and 26 μm thickness, respectively) had a comparatively low sheet resistance (59 and 9 Ω/square, respectively), indicating their good electrical properties, whereas the control rGON2H4 pellet (20 μm thickness) had a high sheet resistance (26 Ω/square).

Figure 3. Characteristic Raman data.

(a) Raman spectra of GO (red), as-prepared rGOC(2 mL-T) using 2 mL thiophene (T) (blue), rGOC(1 mL-T) using 1 mL thiophene (T) (brown), rGOC(0.2 mL-T) using 0.2 mL thiophene (T) (green), rGOCT(2 mL-T) using 2 mL thiophene with chemical reduction followed by thermal treatment (grey) and rGON2H4 by hydrazine (black). (b) Raman spectra of prGO (red) and resultant product from the treatment of prGO with thiophene (black).

Discussion

Therefore, according to our experimental result, we could conclude that the treatment of unique characteristic thiophene followed by thermal treatment produced high-quality rGOs. The as-made rGO nanosheets were well-reduced and formed a well-crystallised graphitic material without any atom impurities. The most effective part is that thiophene can produce rGO that is healed in-situ along with dual reduction with higher mass and highly graphitised rGO. This extensive reduction along with a relatively small average interlayer distance as measured by XRD is probably the main reason for the good electrical properties. This work represents an effective strategy for obtaining high-quality reduced rGO nanosheets by mass-production using a new reducing agent system, which is environmentally friendly.

In summary, the reduction of GO by thiophene was shown to be characterized by significant advantages over other reported procedures. The resulting rGO nanosheets were highly deoxygenated and formed a well crystallized graphitic material without any nitrogen or sulphur impurities. One of the biggest advantages was that the dual functional reduction reaction with thiophene could produce in-situ healed rGOC with a higher mass and highly graphitised rGO in comparison to the reported rGO. Thiophene reduced GO by donation of electrons with acceptance of oxygen while it was converted into an intermediate oxidised and polymerised thiophene that was eventually transformed into polyhydrocarbon by loss of sulphur atoms. Surprisingly, the polyhydrocarbon template helped to produce good-quality rGOC (chemically reduced) and high-quality rGOCT by thermal treatment. The resulting rGOCT nanosheets did not contain any nitrogen and sulphur impurities, were highly deoxygenated and showed a healing effect. Thus the electrical properties of as-prepared rGOCT were better than that of conventional rGON2H4 that requires harsh reaction conditions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first approach to prepare graphene nanosheets using thiophene as a reducing agent. Our XPS, XRD, Raman spectra, TGA, TEM and AFM experimental findings fully supported the formation of high-quality rGO. Our novel dual reduction and healing method using thiophene could potentially save energy and facilitate the commercial mass production of high-quality graphene.

Methods

Preparation of graphene oxide (GO)

GO was prepared from natural graphite powder (Bay Carbon, SP-1 graphite) by the modified Hummers and Offenman's method using sulpuric acid, potassium permanganate, and sodium nitrate32,33.

Reduction of GO with thiophene

GO (10 mg) was dispersed in 10 mL of DI water by stirring at room temperature, followed by the addition of 2 mL of thiophene in round bottom flux. The resultant solution was heated with condenser under N2 atmosphere at 80°C for 24 h. The formed solid material was then collected by filtration (glass frit funnel setup with membrane filter paper 0.45 μm) and washed several times with water, ethanol, dichloromethane and acetone before drying at 60°C for 24 h in a vacuum oven to yield rGO.

SO2 detection

The reaction setup was connected with an outlet, which was dipped into a Ca(OH)2 water solution. The production of white solid CaSO3 was confirmed by Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) (see Supplementary Information video).

Characterization

All X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were made with a SIGMA PROBE (ThermoVG, U.K.) with a monochromatic Al-Kα X-ray source at 100 W, using the Gaussian/Lorenzian sum function. The powder XRD pattern was acquired using a D8-Adcance instrument (Germany) and Cu-Kα radiation. Raman spectroscopy measurements were performed by using a micro-Raman system (Renishaw, RM1000-In Via) with an excitation energy of 2.41 eV (l = 514 nm). The thermal properties of rGO were characterized by TGA (Polymer Laboratories, TGA 1000 plus). AFM was performed with a SPA400 instrument containing a SPI-3800 controller (Seiko Instrument Industry Co.) at room temperature. TEM images were obtained with a JEOL JEM 3010 instrument. The EDX was observed by field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM; JSM-6701F/INCA Energy, JEOL).

Author Contributions

S.S. and H.L. wrote the manuscript. S.S. prepared and characterised all materials. Y.K. and Y.Y. prepared gaphene oxide. H.Y. measured sheet resistance. S.L. measured Raman, Y.P. measured XRD data. H.L. and S.S. supervised the work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Creative Research Initiatives research fund (project title: Smart Molecular Memory) of MEST/NRF.

References

- Geim A. K. & Novoselov K. S. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 183–191 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B. B. et al. All-carbon electronic devices fabricated by directly grown single-walled carbon nanotubes on reduced graphene oxide electrodes. Adv. Mater. 22, 3058–3061 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z. et al. Organic photovoltaic devices using highly flexible reduced graphene oxide films as transparent electrodes. ACS Nano 4, 5263–5268 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankovich S. et al. Graphene-based composite materials. Nature 442, 282–286 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q. et al. Transparent, flexible, all-reduced graphene oxide thin film transistors. ACS Nano 5, 5038–5044 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao C. N. R., Sood A. K., Subrahmanyam K. S. & Govindaraj A. Graphene: the new two-dimensional nanomaterial. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 48, 7752–7777 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z., Lu Y., Somers L. A. & Johnson A. T. C. High yield preparation of macroscopic graphene oxide membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 898–899 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eda G., Fanchini G. & Chhowalla M. Large-area ultrathin films of reduced graphene oxide as a transparent and flexible electronic material. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 270–274 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson N. R. et al. Graphene oxide: structural analysis and application as a highly transparent support for electron microscopy. ACS Nano 3, 2547–2556 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcano D. C. et al. Improved synthesis of graphene oxide. ACS Nano 4, 4806–4814 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankovich S. et al. Synthesis of graphene-based nanosheets via chemical reduction of exfoliated graphite oxide. Carbon 45, 1558–1565 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Shin H.-J. et al. Efficient reduction of graphite oxide by sodium borohydride and its effect on electrical conductance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 19, 1987–1992 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Moon I. K., Lee J., Ruoff R. S. & Lee H. Reduced graphene oxide by chemical graphitization. Nat. Commun. 1, 73–79 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X. et al. Deoxygenation of exfoliated graphite oxide under alkaline conditions: a green Rroute to graphene preparation. Adv. Mater. 20, 4490–4493 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. et al. Reduction of graphene oxide via L-ascorbic acid. Chem. Commun. 46, 1112–1114 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C., Guo S., Fang Y. & Dong S. Reducing sugar: new functional molecules for the green synthesis of graphene nanosheets. ACS Nano 4, 2429–2437 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amarnath C. A. et al. Efficient synthesis of graphene sheets using pyrrole as a reducing agent. Carbon 49, 3497–3502 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Kaminska I. et al. Preparation of graphene/tetrathiafulvalene nanocomposite switchable surfaces. Chem. Commun. 48, 1221–1223 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn S.-H., Czae M., Kim E.-R. & Lee H. Synthesis and characterization of soluble polythiophene derivatives containing electron-transporting moiety. Macromolecules 34, 2522–2527 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer D. R., Jia H.-P. & Bielawski C. W. Graphene oxide: a convenient carbocatalyst for facilitating oxidation and hydration reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 49, 6813–6816 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell E. J. & Campos L. M. The preparation of thiophene-S,S-dioxides and their role in organic electronics. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 12945–12952 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Thiemann T. et al. The chemistry of thiophene S-oxides and related compounds. ARKIVOC 9, 96–113 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Albini F. M., Ceva P., Mascherpa A., Albin E. & Caramella P. Regiochemistry of cycloadditions of nitrile oxides to thiophene and benzothiophene 1, l-dioxides. Tetrahedron 38, 3629–3639 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Payne C. H., Beavers D. V. & Cain R. F. The chemical and preservative properties of sulfur dioxide solution for brining fruit. Agricultural Experiment Station, Oregon State University 629, 1–9 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- Some S. et al. Dual functions of highly potent graphene derivative poly-L-lysine composites to inhibit bacteria and support human cells. ACS Nano 6, 7151–7161 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Some S., Kim Y., Hwang E., Yoo H. & Lee H. Binol salt as a completely removable graphene surfactant. Chem. Commun. 48, 7732–7734 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Some S. et al. Can commonly used hydrazine produce n-type graphene? Chem. Eur. J. 18, 7665–7670 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A. et al. Monitoring dopants by Raman scattering in an electrochemically top-gated graphene transistor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 210215 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M. et al. Production of Graphene Sheets by Direct Dispersion with Aromatic Healing Agents. Small 6, 1100–1107 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M. et al. Fast synthesis of graphene sheets with good thermal stability by microwave irradiation. Chem. Asian. J. 6, 1151–1154 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung V. C., Allen M. J., Yang Y. & Kaner R. B. High-throughput solution Processing of large-scale graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 25–29 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon I. K., Lee J., Ruoff R. S. & Lee H. Reduced graphene oxide by chemical graphitization. Nat. Commun. 1, 73–79 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummers W. S. & Offeman R. E. Preparation of graphitic oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80, 1339 (1958). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.