Abstract

Objective

This study describes how pain practitioners can elicit the beliefs that are responsible for patients’ judgments against considering a treatment change and activate collaborative decision making.

Methods

Beliefs of 139 chronic pain patients who are in treatment but continue to experience significant pain were reduced to seven items about the significance of pain on the patient’s life. The items were aggregated into four decision models that predict which patients are actually considering a change in their current treatment.

Results

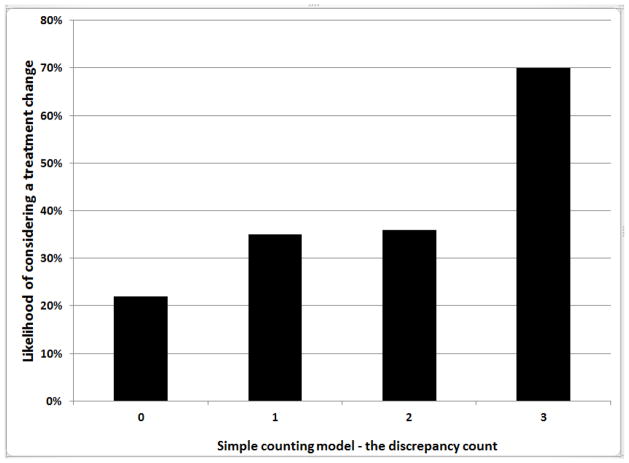

While only 34% of study participants were considering a treatment change overall, the percentage ranged from 20 to 70, depending on their ratings about current consequences of pain, emotional influence, and long-term impact. Generalized linear model analysis confirmed that a simple additive model of these three beliefs is the best predictor.

Conclusion

Initial opposition to a treatment change is a conditional judgment and subject to change as specific beliefs become incompatible with patients’ current conditions. These beliefs can be elicited through dialog by asking three questions.

Keywords: pain, pain management, chronic illness, patient perception of illness, patient-centered care, patient-centered communication, shared decision making, naturalistic decision making

INTRODUCTION

Almost every provider has faced this situation: The patient’s current pain treatment is partially effective, but there is continuing disease activity and functioning limitations. A treatment change is likely to improve the patient’s condition, but when the provider raises this prospect the patient says, “thanks, but I’d rather not make a change.” What happens next is likely to impact the course of future treatment and significantly influence the healthcare relationship (1–3). Epstein and Peters (4)suggest three different ways to respond: persuading the patient to accept the provider’s recommendation, deferring to the patient’s wishes, or beginning a discussion that promotes patient-centered communication and leads to a collaborative decision. This paper joins them in favoring the latter. It describes how practitioners can facilitate patient-centered communication when there is initial disagreement over a prospective treatment change, and how this communication can move toward a collaborative decision.

The first response is paternalistic, insofar as it attempts to bring the patient into concurrence with the recommendation. Paternalism has subtle variations, and discussions between patients and providers frequently have a persuasive element (5). Once there is opposition, efforts to persuade are most likely to be effective if the healthcare relationship is strong and the patient is already motivated to examine their options (6). But as the practitioner becomes more insistent, assertive patients tend to escalate the conflict and become defiant (7), while patients who are fearful, reluctant, or recessive tend to acquiesce. The latter is especially troubling because it reduces self-efficacy and compromises treatment adherence (8, 9). In either case, the relationship is undermined and lost ground is difficult to regain.

The second response affirms the patient’s autonomy, promotes self-efficacy, and encourages self-determination (10–12). Nonetheless, Epstein and Peters refer to it pejoratively as “naive consumerism”(4, p. 197). Sometimes, patients make firm decisions that do not concur with their practitioner’s recommendation. More commonly, unwillingness to consider a change is not a preference or decision, but a conditional judgment that is re-examined as circumstances change. An epidemiological study by Wolfe and Michaud(13)found that most of the rheumatoid arthritis patients they surveyed were unwilling to change their current treatment, even though they were symptomatic. Yet, almost two-thirds said that they would consider a change if their arthritis got worse. Despite its beneficent intent, a deferential response can curtail discussion prematurely and misinterpret a conditional judgment as a clear decision.

Conditional judgments are commonplace in clinical practice. Treatment recommendations are conditioned on diagnostic impressions. Violence risk assessments are conditioned on predictions of future behavior (14). Frequently, interventions are conditioned on meeting a threshold. For instance, the Veterans Administration’s “pain as the 5th vital sign” initiative calls for a comprehensive assessment if the patient’s numeric rating scale pain score is at least 4 (15); rheumatology guidelines recommend a treatment change if disease activity meets a severity criterion. Patients also make conditional judgments in assessing health threats, gauging progress, evaluating quality of service, and reaching treatment preferences(16). As the epidemiological study illustrates, they use different criteria and apply different thresholds. Practitioners are likely to recommend an alternative if there is marked disease activity. Their patients tend to reject an entire class of alternatives—in effect, they dismiss the prospect of change altogether—until they are “getting worse.” Nonetheless, once the threshold is met, patients become open to the possibility of change.

The beliefs and thresholds that predicate patients’ conditional judgments are subject-matter for patient-centered communication. Practical tools have been developed to assist providers in eliciting patients’ beliefs and values and facilitate the discussion. These tools include the health belief model (17), the implicit model of illness (18), the transtheoretical model (19), and the common sense modelor CSM (20, 21). In particular, the CSM was developed to assist in providers in understanding how patients perceive and manage chronic illnesses (22, 23). CSM studies have measured a broad domain of beliefs regarding the course, significance, and timeline of an illness, and the role of treatment (24, 25). They have examined how these beliefs influence coping, self-regulation, emotion, and treatment adherence both immediately and over the life span (26–32). These studies have made it possible to perform a comprehensive assessment of patient experience, but comprehensive instruments are cumbersome and have limited value for clinical practice (33). The CSM is intended as a treatment tool that focuses on domains that are most relevant to specific illnesses, patients, and circumstances. We believe that for chronic pain, these domains include the current consequences of pain, its emotional influence, beliefs about controllability and the effectiveness of treatment, and the long-term impact of pain on the patient’s life.

The CSM is well suited to understanding how patients’ beliefs influence their conditional judgments. Patient-centered communication can make these beliefs explicit (34). But it can do more by facilitating the patient’s involvement in treatment and activating their decision making processes (35). According to Politi and Street (36), collaborative decision making has both communicative and cognitive aspects. The communicative aspects focus on the patient-provider relationship and shared understanding. The cognitive aspects reveal how each party contributes to this shared understanding. For the patient, beliefs and values are aggregated into a schema and form a decision strategy. Traditional behavioral decision making models can shed light on how decision strategies influence patient preferences, but naturalistic models are better suited to describing how the strategy is formed and decision making begins(37). Image theory (38)and its successor, narrative behavioral decision theory (NBDT) (39), are especially appropriate because they portray conditional judgment and preference as distinct but contiguous phases of decision making.

In the epidemiological study reported above (13), most patients judged their current state as compatible with their CSM. They might say that “things are about as expected” and their treatment “is working about as well as it can.” In NBDT, a comparison between what is and what ought to be is called a “discrepancy test.” The study identified a threshold, or point at which the current state becomes incompatible with their beliefs. According to NBDT, incompatibility loosens the hold of the current schema and brings it into question. At this moment, patients project alternatives, then proceed to winnow unacceptable choices and reach a preference. In patient-centered communication, the stepping stones from conditional judgment to preference are experienced and expressed interactively, but each party makes a distinct contribution to the ultimate preference. The following section identifies the beliefs that are pertinent to this process and uses NBDT’s discrepancy test to describe how patients’ beliefs are aggregated into a decision strategy.

METHOD

STUDY PARTICIPANTS AND RECRUITMENT

Patients were recruited from the primary care and women’s clinics of the Connecticut Department of Veterans Affairs medical center’s West Haven and Newington campuses. A Human Subjects Committee-approved protocol included HIPAA and informed consent waivers to perform a limited chart review that identified patients who met three inclusion criteria: 1) non-cancerous musculoskeletal pain in the same location on most days of the month over the past three months;2) living independently or in assisted living facilities;3) age 20–35, 40–55, or 70–89. The latter criterion permitted age-related analyses that are not contained in this report. Patients with an active substance use disorder including opioid dependence, a psychotic disorder, or a dementia were excluded. Candidates were contacted by letter and notified of an impending telephone contact by a research assistant. The letter described an opt-out procedure. A questionnaire was administered to candidates who agreed to be contacted, were reached by telephone, agreed to participate, and signed informed consents. They received $25.00 for participating in a single interview.

DATA COLLECTION

Participants provided demographic information and answered questions about the severity and duration of their pain. Their responses are reported in the results section. Information about co-morbid conditions, obtained from a subsequent chart review, was aggregated into a single measure, using the Charlson comorbidity index (40). Age category and Charleson scores were treated as covariates in the statistical analyses. An18-item questionnaire elicited participants’ common sense models (CSM) of illness and treatment. The items were reduced using empirical procedures described below to produce a small number of items that can be readily incorporated into discussions between patient and provider. The study’s dependent variable was obtained by asking a single yes/no question:”Are you thinking about actually making a change in your current pain treatment?”

CSM ITEM SELECTION PROCEDURE

CSM items were drawn from four domains of the patient’s CSM that we believe are most relevant to chronic pain patients: 1) the current consequences of pain, 2) the emotional influence of pain, 3) controllability of the pain and the effectiveness of treatment, and 4) the long-term impact of pain on the patient’s life. Sixteen items were drawn from the Revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R) (24)and a concurrent longitudinal study conducted by the co-author, who is the principal developer of the CSM (HLL). Two new items were used to assess the long-term impact domain. The 18 items have a 4-or 5-point rating scales.

A principal axis factor analysis was performed to verify that the items assessed the four CSM domains and had at least moderate Varimax-rotated factor loadings(>.50). Four factors had eigenvalues greater than 1 and accounted for 66% of the total variance. The items, eigenvalues, and percent of variance for each factor are contained in Table 1. (The original item order was changed to clarify the results.) Table 1 also reports the highest loading for each item. Loadings for items 11 and 16 were under .5and they were eliminated from further consideration.

TABLE 1.

COMMON-SENSE MODEL ILLNESS BELIEFS, RELATED FACTORS, AND RESULTS OF THE REDUCTION PROCEDURE

| Item No. | Item1 | Rotated factor loading | Threshold value | “Yes” percent below the threshold | “Yes” percent at the threshold | Chi square test of association2 | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current consequences of pain (Eigenvalue=7.48, 41.6% of the variance) | |||||||

| 1 | My illness has major consequences on my life (5+) | .876 | 5: strongly agree | 27 | 46 | 5.182, p=.023 | Selected for discrepancy testing |

| 2 | My illness is a serious condition (5+) | .780 | 5: strongly agree | 27 | 50 | 3.839, p=.05 | Selected for discrepancy testing |

| 3 | My body reminds me every day that I have pain (5+) | .524 | 5: strongly agree | 24 | 42 | 4.628, p=.031 | Selected for discrepancy testing |

| 4 | My illness causes difficulties for those who are close to me (5+) | .616 | 5: strongly agree | 30 | 47 | 2.824, p=.093 | Rejected, non-significant association |

| 5 | How much does your pain affect the quality of your life? (4+) | .648 | No threshold | Rejected, no threshold | |||

| 6 | How much has your pain disrupted your life? (4+) | .570 | No threshold | Rejected, no threshold | |||

| Emotional influence (Eigenvalue=1.89, 10.5% of the variance) | |||||||

| 7 | How worried are you about the effect your pain has on your life now? (4+) | .787 | 4: A lot | 27 | 43 | 3.839(1), p=.05 | Selected for discrepancy testing |

| 8 | How worried are you that your pain will disrupt your life in the future? (4+) | .649 | 4: a lot | 23 | 42 | 5.731 (1), p=.017 | Selected for discrepancy testing |

| 9 | How worried are you about your pain? (4+) | .660 | No threshold | Rejected, no threshold | |||

| 10 | How much does your pain affect you emotionally? (4+) | .590 | No threshold | Rejected, no threshold | |||

| 11 | How worried are you about any of the medications you are taking for your pain? (5+) | .314 | Rejected, low factor loading | ||||

| Controllability and effectiveness of treatment (Eigenvalue=1.39, 7.7% of the variance) | |||||||

| 12 | How much do your treatments actually help your pain? (4−) | .619 | 1: Not at all | 32 | 50 | 1.305, p=.253 | Rejected, non-significant association |

| 13 | How much control do you feel you have over your pain? (4−) | .573 | 1: not at all | 30 | 48 | 3.077, p=.079 | Rejected, non-significant association |

| 14 | My pain is under control most of the time (5−) | .764 | No threshold | Rejected, no threshold | |||

| 15 | Overall, my effforts to keep my pain under control are working very well (5−) | .769 | No threshold3 | Rejected, no threshold | |||

| 16 | How much do you think any treatment can help your pain? (4−) | .454 | Rejected, low factor loading | ||||

| Long-term impact of pain (Eigenvalue=1.08, 5.98% of the variance) | |||||||

| 17 | How satisfied are you with where your life is heading? (4−) | .673 | 1: Not at all | 28 | 59 | 9.695(1), p=.002 | Selected for discrepancy testing |

| 18 | How hopeful are you that you will be able to live a good life? (4−) | .620 | No threshold | Rejected, no threshold | |||

The number in parentheses indicates a 5 point Likert-type scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree) or a 4-point “how much” scale (not at all to a lot). A plus indicates positive-wording, a minues indicates negative wording.

2×2 chi square tests have 1 degree of freedom

Jensen and associates (33)recommend that in clinical practice, assessments of patient beliefs be performed as efficiently as possible, preferably by asking one or two questions. The 16 remaining items were reduced by comparing item scores against the study’s dependent variable. 34% of participants were thinking about actually making a change in their current pain treatment. By cross-tabulating, we obtained the percent of “yes” responses for every rating scale score on all 16 items. The items exhibit a threshold by meeting two conditions:

They have a break-point, a score in which the percent of “yes” answers is higher than the overall 34% percent.

-

For all scores below the break point, the percent of “yes” answers is under 34%.

If the question has negative wording, the percent of “yes” answers must be under 34% for all values that are above the break point.

If the break point is at the middle of the scale, the percent of “yes” answers for scores above the break point must be higher than 34% percent. (For negatively-worded questions, percentages for all scores below the break point must be higher than 34% percent.)

Seven of the 16 items did not exhibit a threshold. For six of these items, the “yes” percentages for every value were under 34%. For item 15, a negative-worded controllability item had a break point at 2, but the “yes” percent at the score of 1 was substantially lower and below 34%. The remaining nine items were collapsed into two categories and their scores were recoded. Ratings at the break point were coded as 1and ratings below the break point were coded as 0. (For the three negative-word items from the controllability and long-term impact domains, scores above the break point were recoded as 0.)

The recoded scores of the nine items were tested for association with the dependent variable. As reported in Table 1, this 2 × 2 chi square test was significant for the six items indicated in bold face. Items 1, 2, and 3 represent the current consequences domain; items 7 and 8 represent emotional influence, and item 17represents long-term impact. None of the controllability items survived the selection procedure: Item 16 had a low factor loading, items 14 and 15 did not exhibit a threshold, and items 12 and 13 had non-significant associations.

DISCREPANCY TESTING, HYPOTHESES, AND DATA ANALYSIS

Discrepancy testing examines how the six beliefs, or a subset, are aggregated into a strategy that activates decision making. The discrepancy test was developed from image theory studies of the “simple counting rule.” The rule proposes that the likelihood of rejecting an alternative increases with the number of incompatible beliefs (41). Regardless of disease activity and clinical indicators, patients who do not experience an incompatibility between their beliefs and the current situation are likely to decline a recommendation to change their current treatment. The likelihood of considering a treatment change increases as the situation becomes less compatible.

The counting rule has been examined in studies of behavioral decision making (41–46)and clinical decision making (47–49). The rule is efficient, additive, and non-compensatory. Because it does not involve a head-to-head comparison between viable alternatives, the counting rule is simpler than the mathematical models that are prominent in the decision making literature. Image theory suggests that expected value maximization and mathematical tradeoff strategies apply to a later stage, after a decision process has begun. The compatibility test occurs earlier and determines whether this process is activated.

Discrepancy testing becomes more complicated if beliefs are weighted differentially (50). For instance, the emotional influence of pain may be more important than its long-term impact. Differential weighting can be represented by a multiplier (like a regression weight)or by unbalancing the belief domains by adding representative items. This study uses the latter approach and compares the simple counting rule to several weighted alternatives.

The simple counting rule is represented by a three-item subset: Item 17in Table 1 is the only candidate from the long-term impact domain; item 1has the highest factor loading of the three candidates in the current consequences domain; item 7has a higher factor loading than the other candidate in the emotional influence domain. A single categorical variable is computed by summing these three recoded items and obtaining a discrepancy count for each patient. The count has four possible values and ranges from 0 to 3. Three differentially weighted rules are computed by supplementing the simple counting rule:

Adding item 8, the other emotional influence item, enhances emotional influence domain.

Adding item 2, the next highest loading current consequences item, enhances the current consequences domain. For the two enhanced models, the discrepancy count ranges from 0 to 4.

Adding both item8 and 2diminishes the long-term impact domain. For this model, the discrepancy count ranges from 0 to 5.

The four counting rules are examined by separate generalized linear models (GLZ). Age group and the Charleson co-morbidity index are treated as covariates. With a logit link function, GLZ is equivalent to binomial logistic regression analysis. It is suitable for analyzing the incremental influence of the discrepancy count on the study’s binomial dependent variable. The significance of each rule is determined by two Wald chi square statistics. One statistic reports the incremental association with the dependent variable; the other reports the linearity of the estimated likelihoods at each value of the discrepancy count. The latter examines whether the likelihood of considering a treatment change increases with the number of discrepant beliefs. Significant rules are compared using Aikaike’s AIC (51), a lower-is-better goodness of fit index. In keeping with the recommendation to assess patient beliefs as efficiently as possible, it is hypothesized that the simple counting rule is significantly associated with the dependent variable and provides the best fit of the four counting rules.

RESULTS

Of 209 candidates who met the record review criteria, did not opt out, were able to be contacted, and met the inclusion criteria, 139 (66%) were interviewed and 70 refused. The demographic and pain-related characteristics of the participants, including their scores on the covariates and dependent variable, are broken down by age group and reported in Table 2. Participants’ ages ranged from 22to 89 and included both genders, but the sample consisted mainly of younger and older males. Demographic characteristics of the 70 who refused are reported at the bottom of the table. Age and gender percentages are similar for participants and decliners; all of the associations between status, gender, and age, were non-significant. The percentage who were actually thinking about making a treatment change was similar across the age groups. The mean pain numeric rating scale of approximately 6 exceeds the threshold of 4 for conducting a comprehensive pain assessment at VA facilities(52). The NRS ranges from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating no “pain at all” and 10 indicating the “worst possible pain.” Four is the threshold score Despite their NRS and a mean duration of more than 13 years, most patients in all three age groups were not actually thinking about making a treatment change. As expected, mean duration and co-morbidity increase with age, and most participants regard their pain as long-standing. Even among the younger group, over 75% believe it will last either “for a long time” or for the remainder of their lives.

TABLE 2.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDY PARTICIPANTS

| Item | Younger (20–35) | Middle (40–55) | Older (70–90) | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 62 (45%) | 28 (20%) | 49 (35%) | 139 |

| Number of males | 46 (74%) | 21 (75%) | 48 (98%) | 115 (83%) |

| Considering a treatment change | 22 (36%) | 10 (36%) | 15 (31%) | 47 (34%) |

| Mean NRS illness severity | 5.95 (2.092) | 6.61 (2.2) | 6.22 (2.143) | 6.18 (2.131) |

| Mean Charleson co-morbidity score | .516 (.621) | 1.57 (1.5) | 2.67 (1.16) | 1.489 (1.416) |

| Mean duration of pain in years | 7.40 (3.766) | 13.11 (11.48) | 21.06 (20.113) | 13.37 (14.483) |

| Course of the pain: | ||||

| Will clear up and go away | 0 (0%) | 2 (7.1%) | 4 (8.2%) | 6 (4.3%) |

| Will get better then come back | 4 (6.5%) | 2 (7.1%) | 2 (4.1%) | 8 (5.7%) |

| Will last for a long time | 12 (1.94%) | 1 (3.6%) | 3 (6.1%) | 16 (11.5%) |

| Will last for the rest of my life | 46 (74.2%) | 23 (82.1%) | 40 (81.6%) | 109 (78.4%) |

| Decliners | ||||

| Age | 22 (31.4%) | 16 (22.9% | 32 (45.7%) | 70 |

| Males | 15 (27.3%) | 12 (21.8%) | 28 (50.9%) | 55 |

standard deviations or percentages are in parentheses

The results of the GLZ analyses are reported in Table 3. The discrepancy count and the linear effect are significant in all four models. Given this finding, the principal issue concerns goodness of fit. The AIC indices confirm the hypothesis that the simple counting rule provides the best fit to the data. The AIC is 8% higher for the emotion-weighted rule, 12% higher for the consequences-weighted rule, and 13% higher for the rule that diminishes long-term effects. Because the AIC index exacts a penalty as the number of parameters increases, the analyses were repeated with the discrepancy count treated as a continuous variable with one degree of freedom. Except for the diminished rule, AIC indices are lower and differences between the simple counting rule and the two weighted rules are smaller. However, the AIC index is lowest in the simple counting rule and the hypothesis is supported.

TABLE 3.

GENERALIZED LINEAR MODEL ANALYSIS OF FOUR DISCREPANCY-BASED DECISION MODELS

| GLZ analysis | Simple counting model | Emotion-weighted model | Consequences-weighted model | Long-term effects diminished model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discrepancy count variable | |||||

| Wald chi square | 10.626 | 13.149 | 12.495 | 18.577 | 20.154 |

| df | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| p | .014 | .011 | .014 | .002 | .017 |

| Discrepancy count linearity | |||||

| Wald chi square | 12.134 | 12.888 | 11.886 | 15.088 | 7.483 |

| df | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| p | .001 | .001 | .002 | .001 | .056 |

| Goodness of fit | |||||

| IV as categorical | 93.591 | 101.135 | 104.932 | 105.788 | 128.743 |

| % increase | 8.06% | 12.12% | 13.03% | 37.56% | |

| Continuous AIC | 91.203 | 97.367 | 100.624 | 104.326 | 124.17 |

| % increase | 6.76% | 10.33% | 14.39% | 36.15% | |

| IV as linear | |||||

| X2 | 9.588 | 10.071 | 10.01 | 11.023 | 11.711 |

| df | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| p | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

DISCUSSION

Work is underway to identify the essential features of patient centered communication, enrich its theoretical framework, and measure its impact on treatment effectiveness and outcome (11, 53–57). This work has not addressed a situation that most practitioners face in working with chronic pain patients: Treatment has been partially effective, but a change is likely to improve the patient’s condition; when this prospect is raised, the patient declines. The current study challenged an assumption shared by paternalistic and consumer-oriented practitioners: that patients who say “thank you, but no” have concluded a decisional process and expressed a preference. Guided by the common-sense model of illness (20), image theory (38), and narrative behavioral decision theory (39), the study proposed that declining an offer to change treatment is a conditional judgment and subject to change. The study identified the beliefs that influence this judgment, the conditions of change, and the strategy that activates patients’ decision processes.

We found that the conditional judgment turns on beliefs about the current consequences of pain, its emotional influence, and its long-term impact on their lives. Symptoms and clinical indicators are crucial to assessment, treatment, and outcome, but as Wolfe and Michaud (13) reported, they do not significantly influence patients’ willingness to change. A finding that seems to conflict with their study concerns the “control” factor. It was not significant in the current study, but in the epidemiological study it was the best single predictor of unwillingness (p. 2137). Item 14 in Table 1 was similar to the question that Wolfe and Michaud used to assess patients’ control over their illness. Item 14 item did not exhibit a threshold, which suggests that most participants in the current study, as with theirs, believed that their pain is reasonably under control. Of the 21 participants (8.6%) who rated this 1 (lowest control), six had 3 simple counting rule discrepancies and ten had 2 discrepancies. A belief that pain is out of control may be represented by discrepancies in beliefs that are directly associated with considering a treatment change: current consequences, emotional influence, and long-term impact.

The study supported the simple counting rule, which gives equal weight to the three beliefs. The mean likelihood estimates for the simple counting rule are shown in Figure 1. With 0 discrepancies, the likelihood considering a treatment change is only 22%. With 1 or 2 discrepancies, the likelihood is still relatively low at 35%, but it jumps to 70% when all three beliefs are discrepant. The results indicate that patients’ beliefs about the prospect of changing their treatment can be assessed efficiently by asking three questions, but one or two questions is not adequate. To illustrate, item 17 is the most sensitive belief, with 59% of participants who rate this item 1 actually considering a treatment change. Depending on the other two discrepancies, this percentage ranges between 40 and 70. Consequently, focusing on any single belief, or even two, is unlikely to give a complete and balanced account of when and why patients are actually considering a change in their current treatment.

FIGURE 1.

MEAN LIKELIHOOD ESTIMATES FOR THE SIMPLECOUNTING RULE

Thresholds are commonly used in clinical practice, but it is unusual to identify thresholds of individual items, then recode them and obtain a count. More commonly, raw scores are summed and the results are put into categories, for instance, as “mild” or “moderate.” An example is the Rapid-4 disease activity assessment (58). To investigate whether a “sum-and-classify” procedure can be used instead of the simple counting rule, we summed items 1, 7, and 17 after collapsing item 1 into a 4-point scale and reversing the scores of item 17. The sum is significant (Wald X2 =20.154, df=9, p=.017); the linear contrast is significant when the sum is treated as a continuous variable (Wald X2 =11.71, df=1, p<.001). Mean likelihood estimates, displayed in Figure 2, show that scores fall roughly into three groups. The estimate is 12% for scores between 3 and 6, 35% for scores between 7 and 11, and 70% for the score of 12. In Figure 1, the likelihood estimate at 0 discrepancies is 20%; otherwise, the percentages are almost identical. Sum-and-classify is useful for tallying questionnaire data, but the simple discrepancy count allows beliefs to be elicited through dialog and is especially useful as a patient-centered communication tool.

FIGURE 2.

MEAN LIKELIHOOD ESTIMATES FOR THE SUM-AND-CLASSIFY PROCEDURE

STUDY LIMITATIONS AND CONCLUSION

The findings presented here should be moderated by the study’s limitations. These include the subject population, which consisted solely of veterans with chronic pain. For the most part, these individuals are male, Caucasian, and not impoverished. Diagnostic data were limited to disease co-morbidities. The study’s sample size was sufficient to identify the beliefs that influence patients’ conditional judgments and determine how decision making is activated. But unlike the Wolfe and Michaud study, the prevalence of the beliefs was not assessed. Illness perception studies have found that beliefs change across the lifespan (59, 60), and older patients are more inclined to accept less than perfect health states than younger patients (61). No studies to date have examined how age affects compatibility testing and the current study lacked sufficient power to investigate this relationship.

The study excluded patients with substance abuse, particularly opioid dependence, and persons with psychotic disorders. These populations present specific complications and challenges, particularly regarding motivation, eliciting meaningful information, and treatment adherence. Future studies should examine the cognitive and interactional factors that influence patient-centered communication in these populations, specifically how compatibility testing affects conditional judgments of opioid-dependent patients.

Many clinicians are familiar with the phenomenon of patient unwillingness to change treatment, but its prevalence, contributing factors, and related problems have not been adequately investigated. (62). Wolfe and Michaud’s report (13)arguably contains the best epidemiological data currently available. However, their study examined patient willingness to change rather than factors that are associated with actually considering a treatment change. Moreover, Wolfe and Michaud’s report is limited to rheumatoid arthritis patients, whereas participants in the current study presented with a variety of pain-related conditions. For rheumatoid arthritis patients, willingness to escalate treatment is directly associated with a poor outcome (63). Nonetheless, escalations do not occur as frequently as recommended, especially if the current treatment is somewhat effective (62). In some cases, unwillingness can be linked directly to patients’ lack of knowledge about their illness, treatment, and treatment options (64, 65). Other factors include lack access to adequate treatment, socioeconomic conditions, referral processes, and contradictory models of patient care (66, 67). Reluctance of physicians to propose a treatment change has also been documented, especially when disease activity is not severe (68).

We suggest that the prevalence data be obtained on factors that contribute to patient willingness to change treatment. “Patient preference,” a commonly used phrase, subsumes a variety of phenomena. It tends to conflate conditional judgments with choices and decisions, and commingle willingness to change with actually considering a change. Future work can break the category of patient preference into more descriptive sets. This work can also examine how practitioners’ beliefs about their patients affects their consideration of a treatment change, and how practitioners’ concerns about undermining the treatment relationship affect patients’ willingness and motivation.

According to Politi and Street (36), collaborative decision making has both communicative and cognitive aspects. This study focused solely on the cognitive aspects and did not describe how the three beliefs are incorporated into patient-provider dialog. Nor did it discuss the importance of communicative aspects such as trust, supportiveness, and interpersonal style (69, 70, 71). We alluded to a movement from conditional judgment to preference and depicted decision making as a two-stage process. We did not describe the crucial role of communication in turning discontinuous phases into a contiguous and integral event. Patient-centered communication is an uncertain process. There is no assurance that eliciting relevant beliefs will activate patients’ decision making or lead to their expressing a preference. Patients who examine alternatives may decide not to change their current treatment. A change may not be congruent with the provider’s recommendation. However, even when a patient-centered response does not result in a treatment change, it can identify barriers to collaboration, assist patients in coping with their pain, and enhance their ability to recognize health threats.

Compatibility between the patient’s beliefs about treatment and their current condition is not always desirable. Those who are relatively satisfied, suffer fewer or lesser consequences, and have minimal worries may be better able to endure unnecessary pain and accommodate functioning limitations. In some instances, the ability to accommodate and adapt exacerbates their condition and causes irrevocable damage. When discrepancy is low in the presence of a significant clinical picture, a worst-of-both response is to persuade the patient to conform the provider’s recommendation, abandon the effort when it proves futile or counterproductive, then send the patient away “to make a decision.” Sandman (5)describes an alternative that he calls a “professionally driven best interest compromise” (p. 62). It attempts to balance the patient’s beliefs and desires against the provider’s knowledge of effective interventions. A compromise is achieved when the provider’s discrepancy threshold is lowered and the patient’s is raised. Some practitioners may be reluctant to increase the patients’ dissatisfaction or to raise their expectations. Others may be hesitant about lowering their standard of practice, even provisionally.

Another alternative is motivational interviewing (MI), which was designed specifically to elicit behavior change by assisting patients to resolve ambivalence (72, p. 326). Two key predicates of MI demonstrate its connection to patient-centered communication. One is that readiness to change is a fluctuating product of interaction and not an individual trait. The other is that eliciting change does not involve “decisional balance” or choices among competing courses of action (73). Instead, the idea is to draw out a patient’s desire to resolve their ambivalence through directive discussion. MI has been linked to patient decision making through the transtheoretical, or “stages of change,” model (19, 74), especially in the pain literature (75). The developers of MI adamantly disclaim this connection (73, p. 130)and favor a patient-centered, discrepancy-testing, approach that is consistent with the ideas expressed in this paper.

What MI and the “best interest compromise” have in common is targeting patients’ dissatisfaction or raising their expectations, and motivating them to take action on the discrepancy. Accomplishing this objective requires time, resources, and training. Practitioners and educators have underscored the importance of training in how to involve patients in collaborative decision making, and noted that training and practice-based learning curricula do not emphasize the requisite skills (55, 76). Others have focused on systemic and organizational barriers and the failure to incorporate patient-centered practices into strategic planning. As a result, resources for education and service coordination are insufficient, and time during consultation to practice patient-centered communication is barely adequate at best (56, 77–79). As Epstein points out, momentum to overcome these barriers begins at the point of service delivery, with efforts to strengthen the healthcare relationship and facilitate patient involvement with their own care (55). Perhaps the findings of this study can assist in this effort.

Acknowledgments

This material is based on work supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development.

Footnotes

Reprints are not available.

Conflicts of interest: None

Contributor Information

Paul R. Falzer, Clinical Epidemiology Research Center, VA Connecticut Healthcare System.

Howard L. Leventhal, Institute for Health, Health Care Policy and Aging Research, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey

Ellen Peters, Department of Psychology, The Ohio State University

Terri R. Fried, Clinical Epidemiology Research Center, VA Connecticut Healthcare System; Department of Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine

Robert Kerns, PRIME Center, VA Connecticut Healthcare System; Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine

Marion Michalski, Department of Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine

Liana Fraenkel, Clinical Epidemiology Research Center, VA Connecticut Healthcare System; Department of Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine.

References

- 1.Braddock CH, Edwards KA. How should physicians involve patients in medical decisions? Reply. JAMA. 2000;283(18):2391–2392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bezreh T, Laws MB, Taubin T, Rifkin DE, Wilson IB. Challenges to physician-patient communication about medication use: A window into the skeptical patient’s world. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6(1):11–18. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S25971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Street RL, Jr, Gordon HS, Ward MM, Krupat E, Kravitz RL. Patient participation in medical consultations: Why some patients are more involved than others. Med Care. 2005;43(10):960–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000178172.40344.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein RM, Peters E. Beyond information. JAMA. 2009;302(2):195–197. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandman L, Munthe C. Shared decision making, paternalism and patient choice. Health Care Anal. 2010;18(1):60–84. doi: 10.1007/s10728-008-0108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elwyn G, Miron-Shatz T. Deliberation before determination: The definition and evaluation of good decision making. Health Expectations. 2010;13(2):139–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kenny DT. Constructions of chronic pain in doctor-patient relationships: Bridging the communication chasm. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52(3):297–305. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werner A, Malterud K. It is hard work behaving as a credible patient: Encounters between women with chronic pain and their doctors. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(8):1409–1419. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00520-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teh CF, Karp JF, Kleinman A, Reynolds CF, III, Weiner DK, Cleary PD. Older people’s experiences of patient-centered treatment for chronic pain: Aqualitative study. Pain Med. 2009;10(3):521–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garrett JR, Lantos JD. Patient autonomy and the twenty-first century physician. Hastings Cent Rep. 2011;41(5) doi: 10.1002/j.1552-146x.2011.tb00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Entwistle V, Carter S, Cribb A, McCaffery K. Supporting patient autonomy: The importance of clinician-patient relationships. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(7):741–745. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1292-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourbeau J. Clinical decision processes and patient engagement in self-management. Dis Manage Hlth Outcomes. 2008;16(5):327–333. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfe F, Michaud K. Resistance of rheumatoid arthritis patients to changing therapy: Discordance between disease activity and patients’ treatment choices. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(7):2135–2142. doi: 10.1002/art.22719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skeem JL, Mulvey EP, Odgers C, Schubert C, Stowman S, Gardner W, et al. What do clinicians expect? Comparing envisioned and reported violence for male and female patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(4):599–609. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mularski R, White-Chu F, Overbay D, Miller L, Asch S, Ganzini L. Measuring pain as the 5th vital sign does not improve quality of pain management. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):607–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Power TE, Swartzman LC, Robinson JW. Cognitive-emotional decision making (cedm): A framework of patient medical decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83(2):163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM. Health behavior and health education. 3. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turk DC, Rudy TE, Salovey P. Implicit models of illness. J Behav Med. 1986;9(5):453–474. doi: 10.1007/BF00845133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prochaska JO. Decision making in the transtheoretical model of behavior change. Med Decis Making. 2008;28(6):845–849. doi: 10.1177/0272989X08327068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Contrada RJ. Self-regulation, health, and behavior: A perceptual-cognitive approach. Psychol Hlth. 1998;13(4):717–733. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mora PA, DiBonaventura MD, Idler E, Leventhal HL, Leventhal EA. Psychological factors influencing self-assessments of health: Toward an understanding of the mechanisms underlying how people rate their own health. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36(3):292–303. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McAndrew LM, Musumeci-Szabo TJ, Mora PA, Vileikyte L, Burns EA, Halm EA, et al. Using the common sense model to design interventions for the prevention and management of chronic illness threats: From description to process. Br J Hlth Psychol. 2008;13(2):195–204. doi: 10.1348/135910708X295604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leventhal HL, Weinman J, Leventhal EA, Phillips LA. Health psychology: The search for pathways between behavior and health. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:477–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moss-Morris R, Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Horne R, Cameron LD, Buick D. The revised illness perception questionnaire (IPQ-R) Psychol Hlth. 2002;17(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, Weinman J. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(6):631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horne R. Treatment perceptions and self-regulation. In: Cameron LD, Leventhal H, editors. The self-regulation of health and illness behavior. New York: Routledge; 2003. pp. 138–153. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leventhal HL, Diefenbach M, Leventhal EA. Illness cognition: Using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cogni Ther Res. 1992;16(2):143–163. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mann DM, Ponieman D, Leventhal HL, Halm EA. Predictors of adherence to diabetes medications: The role of disease and medication beliefs. J Behav Med. 2009;32(2009):278–284. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9202-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hekler EB, Lambert J, Leventhal E, Leventhal H, Jahn E, Contrada RJ. Commonsense illness beliefs, adherence behaviors, and hypertension control among african americans. J Behav Med. 2008;31(5):391–400. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mora PA, Halm E, Leventhal HL, Ceric F. Elucidating the relationship between negative affectivity and symptoms: The role of illness-specific affective responses. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34(1):77–86. doi: 10.1007/BF02879923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rabin C, Leventhal HL, Goodin S. Conceptualization of disease timeline predicts posttreatment distress in breast cancer patients. Health Psychol. 2004;23(4):407–412. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leventhal HL, Rabin C, Leventhal EA, Burns E. Health risk behaviors and aging. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 5. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jensen MP, Keefe FJ, Lefebvre JC, Romano JM, Turner JA. One-and two-item measures of pain beliefs and coping strategies. Pain. 2003;104(3):453–469. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Street R, Haidet P. How well do doctors know their patients? Factors affecting physician understanding of patients’ health beliefs. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(1):21–27. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1453-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michie S, Miles J, Weinman J. Patient-centredness in chronic illness: What is it and does it matter? Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51(3):197–206. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Politi MC, Street RL. The importance of communication in collaborative decision making: Facilitating shared mind and the management of uncertainty. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(4):579–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klein GA, Snowden D, Pin CL. Anticipatory thinking. 8th International Conference on Naturalistic Decision Making; Asilomar Conference Center; Pacific Grove, CA. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beach LR, editor. Imagetheory: Theoretical and empirical foundations. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beach LR. The psychology of narrative thought: How the stories we tell ourselves shape our lives: Xlibris. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A newmethod of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beach LR, Smith B, Lundell J, Mitchell TR. Image theory: Descriptive sufficiency of a simple rule for the compatibility test. J Behav Dec Making. 1988;1(1):17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beach LR, Strom E. A toadstool among the mushrooms: Screening decisions and image theory’s compatibility test. Acta Psychol (Amst) 1989;72(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beach LR, Potter RE. The pre-choice screening of options. Acta Psychol (Amst) 1992;81(2):115–126. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Zee EH, Paluchowski TF, Beach LR. The effects of screening and task partitioning upon evaluations of decision options. J Behav Dec Making. 1992;5(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seidl C, Traub S. A new test of image theory. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1998;75(2):93–116. doi: 10.1006/obhd.1998.2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ordonez LD, Benson L, III, Beach LR. Testing the compatibility test: How instructions, accountability, and anticipated regret affect prechoice screening of options. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1999;78(1):63–80. doi: 10.1006/obhd.1999.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Falzer PR, Garman DM. Contextual decision making and the implementation of clinical guidelines: An example from mental health. Acad Med. 2010;85(3):548–555. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ccd83c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Falzer PR. Expertise in assessing and managing risk of violence: The contribution of naturalistic decision making. In: Mosier KL, Fischer UM, editors. Informed by knowledge: Expert performance in complex situations. New York: Taylor and Francis; 2010. pp. 313–328. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Falzer PR, Garman DM. A conditional model of evidence based decision making. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(6):1142–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beach LR, Puto CP, Heckler SE, Naylor G, Marble TA. Differential versus unit weighting of violations, framing, and the role of probability in image theory’s compatibility test. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1996;65(2):77–82. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bozdogan H. Model selection and akaike’s information criterion (aic): The general theory and its analytical extensions. Psychometrika. 1987;52(3):345–370. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zubkoff L, Lorenz K, Lanto A, Sherbourne C, Goebel J, Glassman P, et al. Does screening for pain correspond to high quality care for veterans? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(9):900–905. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1301-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Epstein RM, Franks P, Fiscella K, Shields CG, Meldrum SC, Kravitz RL, et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in patient-physician consultations: Theoretical and practical issues. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1516–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centered consultations and outcomes in primary care: A review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(1):51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Epstein RM, Street RL., Jr The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):100–103. doi: 10.1370/afm.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Langer M, Langer N. Hospital implementation of patient-centered communication with aging minority populations. Educ Gerontol. 2009;35(10):880–889. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Street RL, Jr, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(3):295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pincus T, Yazici Y, Bergman M. A practical guide to scoring a multi-dimensional health assessment questionnaire (mdhaq) and routine assessment of patient index data (rapid) scores in 10–20seconds for use in standard clinical care, without rulers, calculators, websites or computers. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21(4):755–787. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leventhal EA, Crouch M. Are there differences in peceptions of illness across the lifespan? In: Petrie KJ, Weinman JA, editors. Perceptions of health and illness: Current research and applications. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1997. pp. 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hickey T, Stilwell DL. Chronic illness and aging: A personal-contextual model of age-related changes in health status. Educ Gerontol. 1992;18(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brouwer WB, van Exel NJ, Stolk EA. Acceptability of less than perfect health states. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(2):237–46. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vencovsky J, Huizinga TWJ. Rheumatoid arthritis: The goal rather than the health-care provider is key. Lancet. 2006;367(9509):450–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Hulst LTC, Hulscher MEJL, van Riel PLCM. Achieving tight control in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2011;50(10):1729–31. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Neame R, Hammond A. Beliefs about medications: A questionnaire survey of people with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2005;44(6):762–767. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fraenkel L, Wittink DR, Concato J, Fried T. Informed choice and the widespread use of anti-inflammatory drugs. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(2):210–214. doi: 10.1002/art.20247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suter LG, Fraenkel L, Holmboe ES. What factors account for referral delays for patients with suspected rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis Care Res. 2006;55(2):300–305. doi: 10.1002/art.21855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Townsend A, Adam P, Cox SM, Li LC. Everyday ethics and help-seeking in early rheumatoid arthritis. Chronic Illn. 2010;6(3):171–182. doi: 10.1177/1742395309351963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang J, Shan Y, Reed G, Kremer J, Greenberg JD, Baumgartner S, et al. Thresholds in disease activity for switching biologics in rheumatoid arthritis patients: Experience from a large us cohort. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(12):1672–1679. doi: 10.1002/acr.20643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kraetschmer N, Sharpe N, Urowitz S, Deber RB. How does trust affect patient preferences for participation in decision-making? Health Expect. 2004;7(4):317–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Street RL, Jr, Gordon H, Haidet P. Physicians’ communication and perceptions of patients: Is it how they look, how they talk, or is it just the doctor? Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(3):586–598. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kukla R. How do patients know? Hastings Cent Rep. 2007;37(5):25–35. doi: 10.1353/hcr.2007.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rollnick S, Miller WR. What is motivational interviewing? Behav Cogn Psychother. 1995;23:325–334. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809005128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Miller WR, SR Ten things that motivational interviewing is not. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2009;37(2):129–140. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809005128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Berkowitz SA, Johansen KL. Does motivational interviewing improve outcomes? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(6):463–464. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Burns JW, Glenn B, Lofland K, Bruehl S, Harden RN. Stages of change in readiness to adopt a self-management approach to chronic pain: The moderating role of early-treatment stage progression in predicting outcome. Pain. 2005;115(3):322–331. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Elwyn G, Edwards A, Mowle S, Wensing M, Wilkinson C, Kinnersley P, et al. Measuring the involvement of patients in shared decision-making: A systematic review of instruments. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;43(1):5–22. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Final report DHHSpub No SMA03–3832. Rockville, MD: 2003. Achieving the promise: Transforming mental health care in America. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Berthelot J-M, Blanchais A, Marhadour T, le Goff B, Maugars Y, Saraux A. Fluctuations in disease activity scores for inflammatory joint disease in clinical practice: Do we need a solution? Joint Bone Spine. 2009;76(2):126–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Institute of Medicine. Relieving pain in America: A blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]