Abstract

Objectives

Musculoskeletal pain is highly prevalent throughout adulthood with a major impact on health, function and participation in the society. Still, the association between muscle strength and development of musculoskeletal pain is unclear. We aimed to study whether overall muscle strength in adolescent men is inversely associated with self-reported musculoskeletal pain in adulthood.

Design

Cohort study with baseline data from the Swedish Conscription Register and outcome information from the random population-based Swedish Living Conditions Surveys.

Setting

Sweden, 1970–2005.

Participants

5489 men who at age 17–19 years tested their isometric muscle strength (hand grip, arm flexion and knee extension) during the compulsory conscription.

Outcome measures

The men were surveyed regarding self-reported musculoskeletal pain; mean follow-up time of 17 (range 1–35) years. Our primary outcome was a self-report of musculoskeletal pain, and secondary outcomes were a report of ‘severe pain’, ‘pain in back/hips’, ‘pain in neck/shoulders’ or ‘pain in arms/legs’, respectively. We categorised muscle strength into three groups: low, average and high, using the 25th–75th percentile to define the reference category (average). We estimated relative risks using log binomial regression with adjustment for smoking, body mass index, education and physical activity.

Results

In the adjusted model, men with low overall muscle strength had decreased risk of self-reported musculoskeletal pain (0.93, 95% CI 0.87 to 0.99). We observed no such association in men with high strength (0.99, 0.93 to 1.05). Furthermore, no statistically significant increase or decrease in risk was observed for any of the secondary outcomes.

Conclusions

In men, low overall isometric muscle strength in youth was not associated with an increased risk of future musculoskeletal pain. Contrarily, we observed a slightly decreased risk of self-reported musculoskeletal pain in adulthood. Our results do not support a model in which low muscle strength is a risk factor for future musculoskeletal pain.

Keywords: Sports Medicine, Preventive Medicine

Article summary.

Article focus

We aimed to study whether the overall muscle strength in youth is inversely associated with the development of musculoskeletal pain in adulthood.

Key messages

In contradiction to our expectations, we observed a decreased risk of self-reported musculoskeletal pain in adult men with low overall isometric muscle strength in youth. The study does not provide evidence in support of a theoretical model in which low muscle strength in young men is associated with an increased risk of musculoskeletal pain later in life.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The main strengths of the study are a large sample, the independent evaluation of exposure and outcome, the combined use of three different measures of muscle strength and the comparably long time to follow-up.

The main limitations of the study are the following; the cohort does not include women, musculoskeletal pain only identified with one question per site, the motivation for military service might influence performance in muscle strength testing, and the potential for unmeasured or residual confounding.

Introduction

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), such as low back pain, osteoarthritis and widespread pain, are highly prevalent in the adult population.1–3 MSDs also contribute to a substantial burden of disease at middle and older ages.4 Although pain emanating from the musculoskeletal system might be attributed to a wide range of diseases with diverse causal chains, many MSDs have common risk factors such as heavy occupational work load,5 6 a high body mass index (BMI)7–9 and a low socioeconomy.10–12 Although smoking in some studies have been identified as a risk factor for certain MSDs,13 14 its main effect on musculoskeletal pain might be as an effect modifier of the pain sensation.15 As physical work load is a risk factor for many MSDs,16 a model in which the muscle strength in the loaded parts of the body are protective for future disorders is appealing. This is also the main rationale of studies in the area; does general or demarcated muscle strength have a protective effect on future complaints in the adjacent structures? It is also known that physical exercise with focus on muscle strength is an important secondary and tertiary prevention of MSDs.17 18 A handful of studies have hitherto investigated the strength of isolated muscle groups as a determinant of later MSDs in adulthood.19–22 However, there is conflicting evidence of the value of muscle strength as a protective factor of musculoskeletal pain, such as neck/shoulder pain and low back pain in adult subjects.19

When considering muscle strength in youth as a potential risk factor in the longer perspective, its association with later disease of any kind is relatively unknown, including musculoskeletal pain.23 At least two studies have investigated the result of single muscle strength tests as determinants of musculoskeletal complaints decades later.24 25 The first study, using the number of sit-ups during 30 s as a strength measure, found no association with later low back pain or tension neck in men. In women, the high strength group had a decreased OR of tension neck.24 The second study found a decreased OR for MSDs in men who either had a strong performance in isotonic bench press or in a isometric two hand lift test.25 Neither of the two studies includes a measure of overall muscular capacity. Hence, although there is some evidence of an association between low muscle strength in youth and later risk of MSDs, the association between overall muscle strength in adolescence and later musculoskeletal pain has never been studied. Furthermore, with a larger sample size, data on common risk factors, testing of three different muscle groups and data on physical work capacity, we also address some of the limitations of earlier studies.

Our aim in this study was to investigate the general muscle strength in adolescent men as a determinant of later self-reported musculoskeletal pain. We hypothesised that low general muscle strength in youth is associated with an increased risk of having musculoskeletal pain in adulthood.

Methods

For this prospective register-based cohort study, we used two main inclusion criteria to identify the study sample. First, when typically aged 18, the subjects should have performed mandatory conscription testing in Sweden between 1970 and 1994, with the exception of the years 1978 and 1985. Second, they should have been included in the Swedish Living Conditions Surveys any year between 1980 and 2005 when questions regarding musculoskeletal problems, smoking status and physical activity were simultaneously asked.

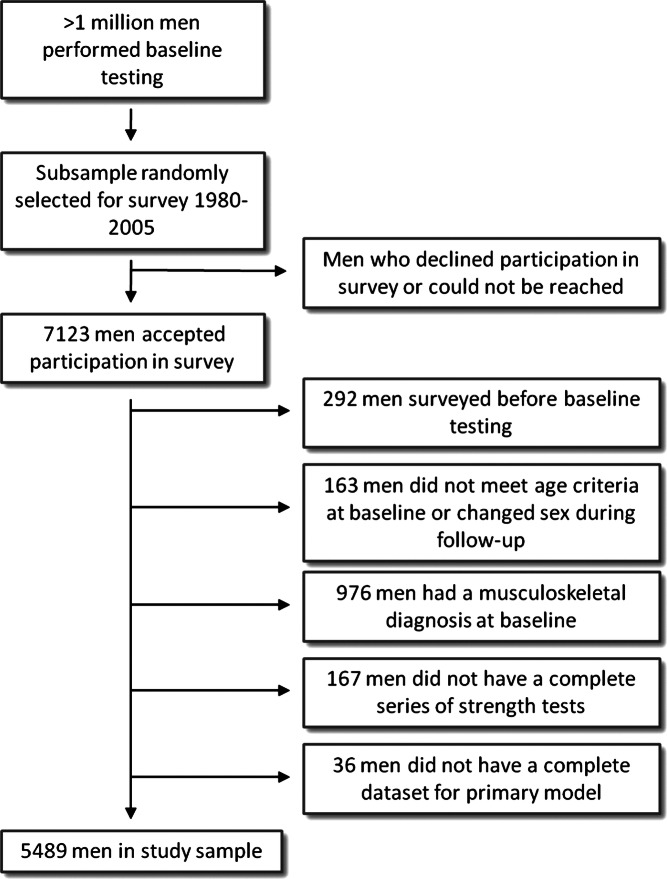

We excluded all men who were surveyed prior to the baseline testing or were younger than 17 years or older than 19 years at baseline (table 1). We also excluded men with an existing MSD (diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue according to the International classification of disease V.8 or V.9) and those who had missing data on variables included in the primary model (muscle strength, smoking, BMI, physical activity, level of education). In the final study sample, we included 5489 men (figure 1). The Swedish conscription register is well characterised and has been used for research purposes previously.26–28 At the time of study sample testing, conscription was mandatory by law for all Swedish men. Specially trained employees at six regional conscription offices administrated the conscription tests during a 2-day session. The procedure also included separate evaluations by a medical doctor and a psychologist. Only men with serious health complaints were excused from conscription. The procedure included the measurements of each man’s weight in underwear to the kilogram and height without shoes to the centimetre. Using height and weight, we calculated BMI as height/kg2. Probably due to rare errors of data entry, there are unlikely extreme values in the dataset. Therefore, we excluded all subjects with registered extreme values on height (<150, >210 cm), weight (<40, >150 kg) or an extreme calculated value for BMI (<15, >60). The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board at Lund University and the manuscript was prepared according to the STROBE-statement.29

Table 1.

Description of study sample

| Number of men | 5489 |

| Mean age at baseline (SD) | 18.2 (0.5) |

| Mean time to follow-up (SD, range) | 17.2 years (8.4, 1–35) |

| Mean hand grip* (SD) | 617 (98) |

| Mean elbow flexion* (SD) | 385 (83) |

| Mean knee extension* (SD) | 567 (116) |

| Muscle strength (%) | |

| Low | 1371 (25.0) |

| Average | 2747 (50.0) |

| High | 1371 (25.0) |

| BMI (%) | |

| <18.5 | 477 (8.7) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 4498 (81.9) |

| 25–29.9 | 448 (8.2) |

| >30 | 66 (1.2) |

| Type of interview (%) | |

| In person | 4349 (79.2) |

| By telephone | 1140 (20.8) |

| Pain in back/hips (%) | |

| Yes | 1645 (30.0) |

| Of which severe | 321 (5.8) |

| No | 3842 (70.0) |

| Missing | 2 (0.0) |

| Pain in neck/shoulders (%) | |

| Yes | 1562 (28.5) |

| Of which severe | 246 (4.5) |

| No | 3925 (71.5) |

| Missing | 2 (0.0) |

| Pain in arms/legs (%) | |

| Yes | 1243 (22.6) |

| Of which severe | 196 (3.6) |

| No | 4243 (77.3) |

| Missing | 3 (0.0) |

| Pain, independent of location (%) | |

| Yes | 2847 (51.9) |

| Of which severe | 576 (10.5) |

| No | 2639 (48.1) |

| Missing | 3 (0.0) |

| Smoking status (%) | |

| Yes | 827 (15.1) |

| No | 4662 (84.9) |

| Level of education (%) | |

| Compulsory | 589 (10.7) |

| Secondary | 2889 (52.6) |

| Higher | 2011 (36.6) |

| Physical activity (%) | |

| Practically none | 583 (10.6) |

| Now and then | 1613 (29.4) |

| Regularly | 2077 (37.8) |

| Regularly strenuous | 1216 (22.2) |

*In Newton.

BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Identification of the study sample and the loss to follow-up.

Muscle strength

The men performed three tests of isometric muscle strength during conscription: hand grip, elbow flexion and knee extension. At the start of test period in 1970, the tests were performed as previously described30 and remained unchanged in general throughout the test period. In summary, hand grip strength on the preferred side was measured with 90° flexion at the elbow and the humerus in parallel to the torso. Knee extension was measured in a sitting position with 90° knee flexion and arms crossed over chest. The pelvis was fixed to the seat and a strap fastened above the lateral malleolus. Also, elbow flexion was measured in a sitting position with 90° flexion at the elbow and the humerus in parallel to the torso. A strap was fastened at the level of the radial styloid process.

We calculated a measure of general muscle strength by standardising and combining the three tests of muscle strength. To avoid bias due to change of testing procedure over time, we categorised the cohort into five subgroups based on the period of conscription (1970–1973, 1974–1977, 1979–1984, 1986–1990, 1990–1994) and for each subcohort calculated the relative muscle strength. First, we standardised the three tests of muscle strength (standardised value=(value−mean)/SD) within each subgroup and used the mean of the three test scores as a proxy for general muscle strength. Using percentiles, we then categorised the cohort into three groups of muscle strength, where the 25th–75th percentile defined the average category, the bottom 25th centile configured the low category and the top 25th centile defined the high muscle strength category.

Survey of musculoskeletal pain

The Swedish Living Conditions Surveys (ULF) is a random population-based survey conducted by Statistics Sweden, previously used for research purposes.31–33 For the present study, we used data collected during a total of 10 years (1980, 1988, 1989, 1997–1999, 2002–2005). The surveys were generally performed as interviews in person by trained interviewers, with a minority of the interviews performed by phone. For men included in more than one survey, we used the last survey without relevant study data missing.

At follow-up, the men were asked three questions regarding any current musculoskeletal pain: (1) Do you have pain in neck or shoulders? (2) Do you have back-pain, hip-pain or sciatica? (3) Do you have ache, pain in hands, elbows, legs or knees? For each type of complaint, one of the three answers was possible: (1) yes, severe; (2) yes, mild and (3) No. Our primary outcome was having reported either severe or mild musculoskeletal pain, whereas our secondary outcomes were defined as follows: (1) having reported severe musculoskeletal pain; (2) having reported pain in back/hips; (3) having reported pain in shoulders/neck and (4) having reported pain in arms/legs. From the surveys, we also included data on self-reported current smoking status (yes/no), physical activity (practically none, now and then, regularly, regularly strenuous) and the level of education (compulsory school or less, secondary education, higher education). Drop-outs from the survey, that is, those who have declined participation, cannot be individually identified. However, during the years of survey used in this study, the participation rate in the survey among men in relevant age groups was 70–88.7%.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed with SAS V.9.3 (SAS Institute Inc). We used logistic binomial regression to estimate relative risks (RR) and control potential confounders. In the multivariate model (primary model), we included muscle strength, BMI, smoking status, physical activity and level of education.

Sensitivity analyses

To test whether cardiorespiratory aspects of physical capacity confounded our results, we used physical work capacity measured as Wmax6 in a sensitivity analysis. For Wmax6, the test result is an estimate of maximum work sustainable for 6 min34 and is in young men correlated with maximum oxygen uptake (r=0.9).35 36 Acceptable data quality on work capacity was available in the subsample of men performing the baseline testing in 1976–1982. Out of all men in the cohort conscripted during the time period, 1154 men (74.6%) completed an acceptable physical work capacity test on a bicycle ergometer (ie, heart rate >174 at the end of testing). We added the work capacity in relation to body weight as a continuous variable to the univariate model. Furthermore, we also performed two sensitivity analyses on the multivariate model with musculoskeletal pain as the dependent variable. In the first, we added test centre to the model. For the second, to test whether our categorisation of muscle strength influenced the results, we used the standardised muscle strength both as a continuous variable and as a categorical variable based on quintiles.

Results

The mean time to follow-up was 17 years (table 1). Men with low muscle strength did not have an increased risk for the primary outcome ‘Musculoskeletal pain’, but rather a statistically significant decreased risk (table 2). To summarise the observations of the secondary outcomes, we did not observe any statistically significant risk increases for men with either low or high muscle strength. Compared with the crude model, the multivariate model produced similar risk estimates.

Table 2.

Risk estimates for the muscle strength in youth as a determinant of self-reported musculoskeletal pain in adulthood

| Outcomes | Models |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate |

Multivariate* |

||||

| Muscle strength |

Muscle strength |

||||

| Low (N=1371) | Average (N=2747) | High (N=1371) | Low | High | |

| RR (N) | Reference (N) | RR (N) | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 0.92 (668) | 1 (1457) | 0.99 (722) | 0.93 (0.87 to 0.99) | 0.99 (0.93 to 1.05) |

| Severe musculoskeletal pain | 0.96 (135) | 1 (283) | 1.12 (158) | 0.96 (0.79 to 1.18) | 1.07 (0.89 to 1.29) |

| Pain in back/hips | 0.92 (384) | 1 (832) | 1.03 (429) | 0.93 (0.84 to 1.03) | 1.03 (0.94 to 1.13) |

| Pain in neck/shoulders | 0.92 (366) | 1 (799) | 0.99 (397) | 0.93 (0.83 to 1.03) | 1.00 (0.90 to 1.10) |

| Pain in arms/legs | 0.97 (297) | 1 (616) | 1.07 (330) | 0.97 (0.86 to 1.10) | 1.06 (0.94 to 1.19) |

*Adjusted for smoking status, physical activity, education, body mass index.

CI, confidence interval; N, number of cases; RR, relative risk estimates.

Work capacity had a significant effect in the subsample analysis (p=0.04), whereas it had only a minor effect on the risk estimates for musculoskeletal pain, being 0.94 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.08) and 1.02 (0.90 to 1.16) for low and high strength, respectively. The pattern of association in the secondary outcomes were in general somewhat strengthened when we adjusted for work capacity (data not shown). Using muscle strength as a continuous variable (hence assuming a linear relationship) did weaken the association with later musculoskeletal pain (p=0.23). When we instead used quintiles to categorise muscle strength, we observed no increased risk for the group with lowest strength compared with average strength (RR=0.93, 0.85 to 1.01).

Discussion

Investigating the general isometric muscle strength in adolescent men as a determinant of future musculoskeletal pain, we observed a decreased risk of self-reported musculoskeletal pain in men with low muscle strength. We also found a similar pattern, however, not statistically significant, for ‘pain in back/hips’ and ‘pain in neck/shoulders’, whereas no association was found for future problems in arms/legs. Noticeably, the current study adds no support to a model in which low muscle strength in men is a risk factor for later musculoskeletal pain.

Using a historical cohort design with prospective registration of exposure and the outcome, the study includes a large sample and thus allows better control for known confounders compared with previous studies. All covariates (muscle strength, BMI, smoking, education, physical activity) included in the multivariate model for musculoskeletal pain also had a significant association with the outcome. Furthermore, by investigating the effects of physical work capacity in a sensitivity analysis, we aimed to isolate the direct effect of muscle strength from other aspects of physical capacity. However, the study also has important limitations. First and foremost, we have used strength data from military conscription testing. Although it provides a rich dataset from a structured environment, we do not know how the subjects’ motivation for military service may have biased the performance during the testing procedure. However, assuming that there is no association between motivation at conscription testing and later risk of musculoskeletal pain (or the loss to follow-up) any bias would at most dilute our result. Nevertheless, stronger recruits are more likely to be assigned to positions with heavy load duty. Second, the conscription was mandatory for men only. As the pattern of physical activity and occupational exposure differ between men and women, any generalisation of the results to women must be made with great caution. Third, the physical activity measurement consisted of a single question and did neither allow calculation of metabolic equivalent of task nor included occupational exposure. Also, musculoskeletal pain is measured by questions that combine more than one site, decreasing the precision. However, the categories are fairly well-demarcated anatomically save for the question regarding pain in arms/legs. Fourth, the covariates collected with musculoskeletal pain at follow-up (smoking, physical activity, level of education) are cross-sectional and might thus be mediators of reverse causation. However, the adjusted estimates are much in line with the crude estimates.

Primarily, we do not suggest that low muscle strength in youth is a protective factor for later musculoskeletal pain. However, our observations could potentially be explained by both social and biological factors. First, as former occupational exposure16 and certain sport participation37 are established risk factors for future MSDs, it lend some evidence for a general model in which certain forms of physical activity are negative for the musculoskeletal health. It has also previously been suggested that there is a U-shaped association between physical activity and later back pain,38 39 that is, those participants with low and high levels of physical activity have an increased risk compared with the group with average activity. First, we speculate that our results may be explained by muscle strength in youth being one selection criterion for future high risk activities with a negative influence on the musculoskeletal health, for example, higher risk of joint injury due to sports participation or manual repetitive work load. This would also include more immediate exposure in youth such as more physically demanding military service.40 Although we have controlled for the level of education, which we regard as a proxy for occupational exposure, there is potential for residual confounding. In other words, individuals with low general muscle strength might to a certain degree be deselected for high risk activities compared with stronger men. A second potential explanation for our observation can be based on that the strength of an individual is associated with the muscle fibre type distribution, which has a large genetic component.41 While type I fibres are more common in endurance athletes,42 a high type II percentage has been reported to be associated with both isometric muscle strength43 as well as low back pain.44

It is important to note that our main result is not the significantly decreased risk of later musculoskeletal pain observed in men with low strength, but the non-existent risk increases in the same group. This is partly in contrast with one of the few previous studies in the area. Although we in the present study only include the measurements of isometric strength, the previous study25 reported associations with both an isometric strength measure (static two hand lift) and an isotonic strength measure (bench press). In another study on the same cohort, it is reported that the result in bench press, but not two hand lift, was associated with both future cardiorespiratory fitness and future physical activity,45 potentially explaining part of the difference. Another study reported flexibility as a sit and reach test,24 but not strength measured as sit-ups, to be negatively associated with future risk of back pain. Hence, it is possible that other aspects of muscular and musculoskeletal function are of greater importance for the future risk of MSDs than the isometric muscle strength as such.

The association between muscle strength and later musculoskeletal pain diminished when we used muscle strength as a continuous variable. This was not surprising, as the observed association was non-linear in the primary model. It is to be expected that the test offices differ somewhat in their reported test results, as they were assigned adolescents based on geography. However, including test offices in the model did not have any effect on the overall association. When we included work capacity in the model, most risk estimates decreased in absolute values, furthering strengthening the observations in the primary model. By using the relative muscle strength during testing periods of 5 years, we partially address the potential systematic change in testing procedure over the years. Although the methods of measurements have not changed at large, minor adjustments cannot be excluded.

In future studies, it would be of interest to investigate if low muscle strength serves as a deselection criterion for professions or types of leisure time physical activity with higher risk of acute injuries or chronic physical overload, factors with negative impact on musculoskeletal health. Since the physical activity pattern and physical fitness profiles differ between men and women, further investigations are also needed to investigate if similar associations can be found in women.

In conclusion, we observed no increased risk of self-reported musculoskeletal pain in adult men with low overall isometric muscle strength in youth. Thus, this study adds no support to a model in which muscle strength is a risk factor for future musculoskeletal pain in men.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Charlotte Bergknut for the initial data management.

Footnotes

Contributors: ST proposed the study idea, collected data, designed the study, and drafted the manuscript. IFP designed the study and provided input during manuscript preparation. CZ designed the study and performed the statistical analyses. ME designed the study, collected data and provided input during manuscript preparation. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors are supported by grants from The Swedish Research Council, Skåne Regional Council, and the Faculty of Medicine at Lund University. The funders neither influenced the study process nor manuscript preparation.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethical Review Board of Lund University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Bergman S, Herrstrom P, Hogstrom K, et al. Chronic musculoskeletal pain, prevalence rates, and sociodemographic associations in a Swedish population study. J Rheumatol 2001;28:1369–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Picavet HS, Schouten JS. Musculoskeletal pain in the Netherlands: prevalences, consequences and risk groups, the DMC(3)-study. Pain 2003;102:167–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urwin M, Symmons D, Allison T, et al. Estimating the burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the community: the comparative prevalence of symptoms at different anatomical sites, and the relation to social deprivation. Ann Rheum Dis 1998;57:649–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;380:2197–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Der Windt DA, Thomas E, Pope DP, et al. Occupational risk factors for shoulder pain: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med 2000;57:433–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoogendoorn WE, Van Poppel MN, Bongers PM, et al. Physical load during work and leisure time as risk factors for back pain. Scand J Work Environ Health 1999;25:387–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felson DT, Zhang Y, Hannan MT, et al. Risk factors for incident radiographic knee osteoarthritis in the elderly: the Framingham Study. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:728–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiri R, Karppinen J, Leino-Arjas P, et al. The association between obesity and low back pain: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2010;171:135–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grotle M, Hagen KB, Natvig B, et al. Obesity and osteoarthritis in knee, hip and/or hand: an epidemiological study in the general population with 10 years follow-up. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2008;9:132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagen K, Zwart JA, Svebak S, et al. Low socioeconomic status is associated with chronic musculoskeletal complaints among 46,901 adults in Norway. Scand J Public Health 2005;33:268–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalstra JA, Kunst AE, Borrell C, et al. Socioeconomic differences in the prevalence of common chronic diseases: an overview of eight European countries. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:316–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bengtsson C, Nordmark B, Klareskog L, et al. Socioeconomic status and the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis: results from the Swedish EIRA study. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1588–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmer KT, Syddall H, Cooper C, et al. Smoking and musculoskeletal disorders: findings from a British National Survey. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:33–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holth HS, Werpen HK, Zwart JA, et al. Physical inactivity is associated with chronic musculoskeletal complaints 11 years later: results from the Nord-Trondelag Health Study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2008;9:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McBeth J, Jones K. Epidemiology of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2007;21:403–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roquelaure Y, Ha C, Rouillon C, et al. Risk factors for upper-extremity musculoskeletal disorders in the working population. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1425–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hakkinen A, Sokka T, Kotaniemi A, et al. A randomized two-year study of the effects of dynamic strength training on muscle strength, disease activity, functional capacity, and bone mineral density in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:515–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker KR, Nelson ME, Felson DT, et al. The efficacy of home based progressive strength training in older adults with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol 2001;28:1655–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamberg-van Reenen HH, Ariens GA, Blatter BM, et al. A systematic review of the relation between physical capacity and future low back and neck/shoulder pain. Pain 2007;130:93–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leino P, Aro S, Hasan J. Trunk muscle function and low back disorders: a ten-year follow-up study. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:289–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kujala UM, Taimela S, Viljanen T, et al. Physical loading and performance as predictors of back pain in healthy adults. A 5-year prospective study. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1996;73:452–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faber A, Sell L, Hansen JV, et al. Does muscle strength predict future musculoskeletal disorders and sickness absence? Occup Med (Oxford, England) 2012;62:41–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruiz JR, Castro-Pinero J, Artero EG, et al. Predictive validity of health-related fitness in youth: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:909–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mikkelsson LO, Nupponen H, Kaprio J, et al. Adolescent flexibility, endurance strength, and physical activity as predictors of adult tension neck, low back pain, and knee injury: a 25 year follow up study. Br J Sports Med 2006;40:107–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnekow-Bergkvist M, Hedberg GE, Janlert U, et al. Determinants of self-reported neck-shoulder and low back symptoms in a general population. Spine 1998;23:235–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neovius M, Sundstrom J, Rasmussen F. Combined effects of overweight and smoking in late adolescence on subsequent mortality: nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2009;338:b496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nilsson PM, Nyberg P, Ostergren PO. Increased susceptibility to stress at a psychological assessment of stress tolerance is associated with impaired fetal growth. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:75–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hemmingsson T, Melin B, Allebeck P, et al. The association between cognitive ability measured at ages 18–20 and mortality during 30 years of follow-up—a prospective observational study among Swedish males born 1949–51. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:665–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007;335:806–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nordesjo LO, Schéle R. Validity of ergometer cycle test and measures of isometric muscle strength when predicting some aspects of military performance. Swedish J Defence Med 1974;10:11–23 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolk A, Rossner S. Effects of smoking and physical activity on body weight: developments in Sweden between 1980 and 1989. J Intern Med 1995;237:287–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sundquist J, Johansson SE. The influence of socioeconomic status, ethnicity and lifestyle on body mass index in a longitudinal study. Int J Epidemiol 1998;27:57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bygren LO, Konlaan BB, Johansson SE. Attendance at cultural events, reading books or periodicals, and making music or singing in a choir as determinants for survival: Swedish interview survey of living conditions. BMJ 1996;313:1577–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tornvall G. Assessment of physical capabilities. Acta Physiol Scand 1963;58(Suppl 201):1–10214013176 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nordesjo LO. A comparison between the Thornvall maximal ergometer test, submaximal ergometer tests and maximal oxygen uptake. Swedish J Defence Med 1974;10:3–10 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nordesjo LO. Estimation of the maximal work rate sustainable for 6 minutes using a single-level load or stepwise increasing loads. Ups J Med Sci 1974;79:45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kujala UM, Kettunen J, Paananen H, et al. Knee osteoarthritis in former runners, soccer players, weight lifters, and shooters. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:539–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heneweer H, Picavet HS, Staes F, et al. Physical fitness, rather than self-reported physical activities, is more strongly associated with low back pain: evidence from a working population. Eur Spine J 2012;21:1265–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heneweer H, Vanhees L, Picavet HS. Physical activity and low back pain: a U-shaped relation? Pain 2009;143:21–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Almeida SA, Williams KM, Shaffer RA, et al. Epidemiological patterns of musculoskeletal injuries and physical training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1999;31:1176–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simoneau JA, Bouchard C. Genetic determinism of fiber type proportion in human skeletal muscle. FASEB J 1995; 9:1091–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costill DL, Daniels J, Evans W, et al. Skeletal muscle enzymes and fiber composition in male and female track athletes. J Appl Physiol 1976;40:149–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tesch P, Karlsson J. Isometric strength performance and muscle fibre type distribution in man. Acta Physiol Scand 1978; 103:47–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mannion AF, Weber BR, Dvorak J, et al. Fibre type characteristics of the lumbar paraspinal muscles in normal healthy subjects and in patients with low back pain. J Orthop Res 1997;15:881–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barnekow-Bergkvist M, Hedberg G, Janlert U, et al. Prediction of physical fitness and physical activity level in adulthood by physical performance and physical activity in adolescence—an 18-year follow-up study. Scand J Med Sci Sports 1998;8(5 Pt 1):299–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.