Abstract

Background

Mind-body practices are increasingly used to provide stress reduction for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Mind-body practice encompasses activities with the intent to use the mind to impact physical functioning and improve health.

Methods

This is a literature review using PubMed, PsycINFO, and PILOTS to identify the effects of mind-body intervention modalities, such as yoga, taichi, qigong, mindfulness-based stress reduction, meditation, and deep breathing, as interventions for PTSD.

Results

The literature search identified 92 articles, only 16 of which were suitable for inclusion in this review. We reviewed only original, full text articles that met the inclusion criteria. Most of the studies have small sample size, but findings from the 16 publications reviewed here suggest that mind-body practices are associated with positive impacts on PTSD symptoms. Mind-body practices incorporate numerous therapeutic effects on stress responses, including reductions in anxiety, depression, and anger, and increases in pain-tolerance, self-esteem, energy levels, ability to relax, and ability to cope with stressful situations. In general, mind-body practices were found to be a viable intervention to improve the constellation of PTSD symptoms such as intrusive memories, avoidance, and increased emotional arousal.

Conclusions

Mind-body practices are increasingly employed in the treatment of PTSD and are associated with positive impacts on stress-induced illnesses such as depression and PTSD in most existing studies. Knowledge about the diverse modalities of mind-body practices may provide clinicians and patients with the opportunity to explore an individualized and effective treatment plan enhanced by mind-body interventions as part of ongoing self-care.

Keywords: mindfulness, exercise, breathing, yoga, taichi, posttraumatic stress disorder

INTRODUCTION

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an anxiety problem that may develop in some people after exposure to extremely traumatic events, such as combat, crime, an accident, or a natural disaster.1 In any given year, 7.7 million Americans over the age of 18 are diagnosed with PTSD,2 a debilitating disorder that is often comorbid with other diseases.3 Individuals with PTSD suffer substantial social and interpersonal problems, as well as impaired quality of life stemming from the long-term presence of the intrusive, avoidant and hyperaroused symptoms that characterize the disease. Concomitantly, PTSD patients show characteristics of higher sympathetic and lower parasympathetic activity at basal levels compared to healthy individuals4 as measured by low heart rate variability (HRV).5 Although conventional pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions have shown some proven efficacy in the treatment of PTSD,6 residual symptoms and therapeutic efficacy remain problematic. Recently, a variety of integrative mind-body intervention modalities have emerged that are increasingly employed in the treatment of PTSD. This growing body of evidence has shown that mind-body interventions have a positive impact on quality of life, stress reduction, and improvement of health outcomes among individuals with PTSD. 7-17 In 2010, 39 percent of individuals with PTSD reported using complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) interventions, including mind-body practices that incorporate various types of stretching movements and postures combined with deep breathing (e.g., yoga, taichi, qigong, and meditation).3 Furthermore, there is emerging evidence that supports the neural and biological mechanisms underlying mind-body practices for the management of stress-related illness.18-21 Studies have shown that stress-related disorders may be induced by allostatic load,22 the “body cost” for maintaining homeostasis, and imbalance in the autonomic nervous system (ANS), with over-activity of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and under-activity of the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS).5 Streeter and colleagues proposed that mind-body interventions such as yoga may be associated with reduction of PTSD symptoms by normalizing the imbalance in ANS and increasing PNS activity.5

The purpose of this article, therefore, is to review the evidence that evaluates the effectiveness of mind-body practices as complementary and/or alternative treatment for individuals with PTSD. Although there are overlaps between the methods used in conventional therapies and mind-body practices (i.e., breathing techniques, relaxation, imagery, and hypnosis), for the sake of this review we define mind-body practices as interventions with components of interaction among the mind, body, and behavior, with the intent to integrate these three components in the pursuit of improved physical functioning, and mental and physical health.23

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Scope of the Review

We searched for peer-reviewed original journal articles in English on the effects of mind-body practices as interventions to treat PTSD. Mind-body practices were defined to include physical activities that focus on interaction among brain, body and behavior, including yoga, taichi, qigong, mindfulness-based stress reduction, meditation, and deep breathing. We included demographics, PTSD symptoms (e.g., intrusive thought, flashback, avoidance, numbness, hyperarousal), and heart rate variability (HRV) as topics of interest.

Search Strategy

Our literature searches of PubMed/MEDLINE, EBSCO/PsycINFO, and the Published International Literature on Traumatic Stress (PILOTS) database took place on June 27, 2012. We used combinations of the search terms “mindfulness” or “mind-body”, and “exercise” or “yoga” or “taichi” or “qigong” or “meditation”, and “posttraumatic stress disorder” or “PTSD”.

Inclusion Criteria

We initially screened abstracts published in English that included human participants with PTSD. Those abstracts included randomized control trials, comparative studies, and observational studies that evaluated the efficacy of mind-body interventions on PTSD symptom changes. For articles that passed the initial screening, we retrieved the full articles to assess eligibility.

RESULTS

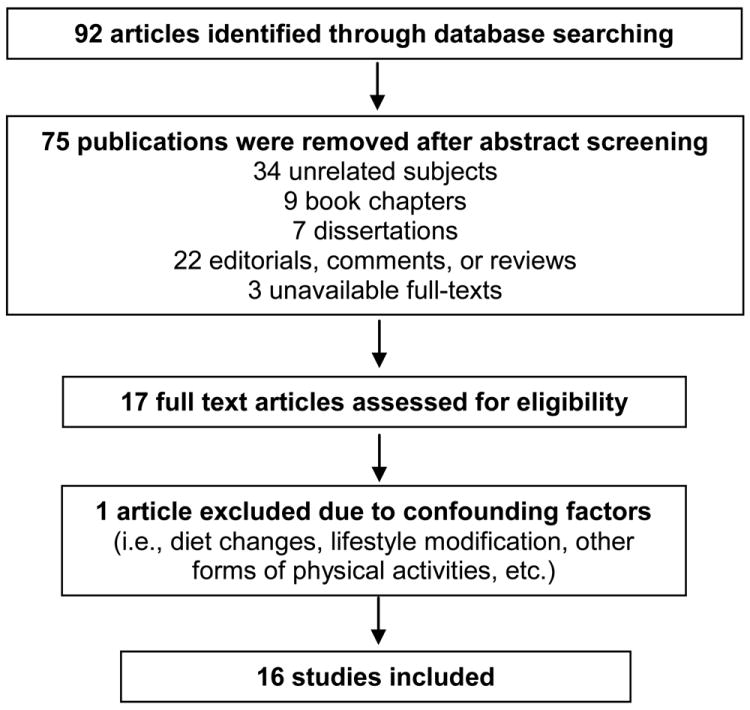

We screened 92 English language abstracts and selected for review a total of 16 articles that met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Six randomized controlled trials (RCT), 1 randomized non-controlled study (RT), 8 non-randomized studies (NRS), and 1 observational non-controlled study (OBS) with a total of 1,065 participants were selected for review (Table 1). Seventy-five publications did not meet the inclusion criteria: 34 articles were unrelated to the study subject, 9 were from book chapters, 7 were dissertations, 22 were editorials or reviews, and 3 journals were unavailable. Twenty-six articles overlapped across more than two search engines. Two articles were available only in PubMed. One article was not included in the review due to the large number of simultaneous interventions (i.e., diet changes, lifestyle modification, other forms of physical activity) conducted in addition to the mind-body intervention, making it impossible to identify which changes were attributable solely to mind-body practices. Of the 16 studies reviewed, 9 did not have a control group; 4 examined a mind-body intervention as adjunct to treatment as usual and 12 as a monotherapy. Two studies examined the effects of yoga; 5 evaluated the effects of meditation, or meditation and relaxation; 1 the effects of taichi and qigong; 3 the efficacy of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR); 1 the effect of a portable practice of repeating a mantram; 1 the effects of relaxation, or relaxation plus deep breathing, or relaxation plus deep breathing and thermal biofeedback; and 3 studies examined the effects of mind-body skills (a combination of various mindfulness-based approaches). Twelve studies reported significant positive effects of mind-body interventions on reduction of PTSD symptoms via regulation of the sympathetic and/or parasympathetic nervous systems (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Flow of the systematic review process.

TABLE 1.

Studies of Mind-body Interventions in Patients with PTSD

| Author Year Study Site | Study Design | Mean age (SD) Gender (%) | Intervention Time Frame Sample Size | PTSD Outcomes, Magnitude of Symptom Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descilo et al.7 2010 U.S. | NRS | Adult | Yoga breathing | 60% decrease in PTSD symptom severity at weeks 6, 24 |

| 30.8 | 5 weeks | |||

| Female (85) | N = 183 | ΔPCL-17 = -42.5 | ||

| Staples et al.8 2011 Gaza | NRS | Age | Mind-body skills | Significant effect of time for PTSD subscales. |

| 13.3 | 5 weeks | |||

| Female (37) | N = 129 | ΔCPSS = 16.8 | ||

| Telles et al.26 2010 India | RCT | Adult | Yoga | No significant changes in the HRV. |

| 31.5 (7.5) | 1 week, 60 min daily | |||

| Male (100) | N = 22 | ΔpNN50 = 7.83 | ||

| Stankovic L.27 2011 U.S. | NRS | Adult | Meditation (iRest) | Subjective rating of permanence of positive symptom changes = 3.27 out of 1 (temporary) to 5 (permanent). |

| 61 | 8 weeks, 40-min weekly | |||

| Not specified | ||||

| N = 16 | ||||

| Watson et al.24 1997 U.S. | RCT | Adult | Relaxation, breathing, biofeedback | Moderate effect of relaxation, but not breathing and/or biofeedback in PTSD treatment. |

| 45.6 | ||||

| Male (100) | 10 sessions | |||

| N = 90 | ΔPTSD-I = -0.4 | |||

| Branstrom et al.25 2011 Sweden | RCT | Adult | MBSR | No significant changes in overall PTSD symptoms but avoidance. |

| 51.8 (9.86) | 8 sessions, 2-h weekly | |||

| Female (99) | N = 71 | ΔIES = -6.42 at 6-month follow-up | ||

| Bormann et al.9 2011 US | RCT | Adult | Mantram | Significant PTSD symptom reduction. |

| 56.1 (9.60) | 6 sessions, 90-min weekly | |||

| Male (97) | N = 136 | ΔPCL-C = -6.3 | ||

| Catani et al.10 2009 Sri Lanka | RCT | Children | Meditation-relaxation | Significant PTSD symptom reduction |

| 11.95 | 2 weeks, 6 sessions | |||

| Male (54.8) | N = 31 | ΔUPID = -23.99 at wk2 | ||

| Gordon et al.11 2004 Kosovo | NRS | Adolescents | Mind-body skills | Significant PTSD symptom reduction at posttest. |

| Pilot | 16-19 (88%) | 6 weeks | ||

| Male (54) | N = 139 | ΔPTSD-RI = -2.2 | ||

| Gordon et al.12 2008 Kosovo | RCT | Adolescents | Mind-body skills | Significant decrease in PTSD symptom severity. |

| 16.3 | 6 weeks, twice weekly | |||

| Female (62) | N = 82 | ΔHTQ = -0.5, -0.4 at wks 6, 12 | ||

| Grodin et al.13 2008 U.S. | OBS Case study | Adult (Foreign patients) | Taichi and Qigong >1 year | Decreased re-experiencing, flashbacks, anxiety, and stress Increased equanimity Improved pain Soothing effect. |

| Age = 23, 30, 44, 47 | N = 4 | |||

| Male (75) | ||||

| Waelde et al.14 2004 U.S. | NRS | Adult | Meditation | Significant decrease in PTSD symptom and stress coping. |

| 49 (11) | 8 weeks, daily 30 min | |||

| Female (85) | N = 20 | ΔPCL-S = -6.03 | ||

| Brooks and Scarano28 1985 U.S. | RT | Adults | Meditation | Significant decrease in symptoms of post-Vietnam stress disorder the intervention group. |

| 33.3 | 3 months | |||

| Male (100) | N = 18 | |||

| ΔPVSD = -3.90 | ||||

| Kimbrough et al.15 2010 U.S. | NRS | Adult | MBSR | PTSD symptom severity improved by 31% after 8-week MBSR. |

| 45 (10.8) | 8 weeks | |||

| Female (89) | N = 27 | ΔPCL-C = -14.5 | ||

| Rosenthal etal.16 2011 U.S. | NRS | Adult | Meditation | Significant improvement in PTSD symptom severity. ΔCAPS = -31.4 |

| 41.5 (16.6) | 8 weeks, 20 minutes, twice a day | |||

| Male (100) | ΔPCL-M = -24.00 | |||

| N=5 | ||||

| Kearney et al.17 2012 U.S. | NRS | Adult | MBSR | Significant improvement in PTSD symptom severity. |

| 51(10.6) | 8 weeks | |||

| Male (75) | N = 92 | ΔPCL-C = -9 |

Data are shown as mean (SD) for quantitative variables and mean (%) for gender.

Abbreviations: NRS, prospective nonrandomized studies; RCT, randomized controlled trial; OBS, observational non-controlled study; RT, randomized-noncontrolled trial; MBSR, mindfulness-based stress reduction; PCL-C, PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version; CPSS, Child PTSD Symptom Scale; HRV, heart rate variability; pNN50, the percentage of successive normal cardiac interbeat intervals greater than 50 msec; IES, Impact of Event Scale; UPID, UCLA PTSD Index for DSM-IV; PTSD-RI, PTSD Reaction Index; HTQ, Harvard Trauma Questionnaire; PCL-S, PTSD Checklist-Specific Version; PVSD, Post-Vietnam Stress Disorder; CAPS, the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; PCL-M, PTSD Checklist-Military Version.

TABLE 2.

Changes in PTSD Symptom Severity

| Author | Instrument/Dependent Variable | Symptom Severity

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Changes in Mean | P | ||

| Descilo et al.7 | PCL-17/PTSD Symptoms | 66.5 | 23.9 | -42.5 | <0.001 |

| Staples et al.8 | CPSS total | 30.0 (6.8) | 13.2 (7.3) | -16.8 | 0.0001 |

| CPSS subscales | |||||

| Reexperiencing | 8.3 (2.8) | 3.9 (2.7) | -4.4 | ||

| Avoidance | 12.3 (3.0) | 5.3 (3.4) | -7.0 | ||

| Arousal | 9.4 (2.6) | 3.9 (2.9) | -5.5 | ||

| Telles et al.26 | HRV | LF: 56.54 | LF: 55.76 | LF: -0.78 | > 0.05 |

| Vagal Activity | HF: 43.40 | HF: 44.19 | HF: -0.79 | ||

| LF/HF: 1.23 | LF/HF: 1.77 | LF/HF: -0.54 | |||

| pNN50: 13.33 | pNN50: 21.16 | pNN50: -7.83 | |||

| Stankovic L.27 | Weekly questionnaire | Difficulty distinguishing between simple and complex emotions (e.g., numbing) | Increased awareness and physical mobility | Subjective rating of symptom changes = 3.27 | |

| iRest worksheet | |||||

| Recorded in-class discussion | Reduced physical pain, anxiety, anger, and self-judgment | ||||

| Final questionnaire | |||||

| PTSD Symptoms | Long-term guilt, grief, and rage | Improved ability to relax | |||

| Lack of hope | |||||

| Watson et al.24 | PTSD-I/PTSD Symptoms | Rx: 95.4 | Rx: 95.0 | Rx: -0.4 | > 0.05 |

| RxBr:98.1 | RxBr:97.8 | RxBr:-0.3 | |||

| RxBrTb: 90.5 | RxBrTb: 89.4 | RxBrTb: -1.1 | |||

| Branstrom et al.25 | IES/PTSD Symptoms | IES-intrusion: 13.28 (7.07) | IES-intrusion: 11.81 (6.36) | IES-intrusion: -1.47 | >0.05 |

| IES-avoidance: 10.55 (6.79) | IES-avoidance: 7.88 (7.65) | IES-avoidance: -2.67 | |||

| IES-hyperarousal: 9.50 (5.51) | IES-hyperarousal: 7.22 (5.24) | IES- hyperarousal: -2.28 | |||

| Bormann et al.9 | PCL-C/PTSD Symptoms | 61.8 (11.50) | 55.5 (11.20) | -6.3 | 0.02 |

| Catani et al.10 | UPID/PTSD Symptoms | 36.58 (14.9) | 12.59 (11.06) | -23.99 | 0.0001 |

| Gordon et al.11 | PTSD-RI/PTSD Symptoms | Group I: 8.3 | Group I: 6.1 | -2.2 | < 0.001 |

| Group II: 10.8 | Group II: 5.8 | -5.0 | < 0.001 | ||

| Group III: 11.4 | Group III: 5.5 | -5.9 | < 0.001 | ||

| Gordon et al.12 | HTQ | 2.5 (0.3) | 2.0 (0.3) | -0.5 | < 0.001 |

| % of subjects w/PTSD | |||||

| Reexperiencing | 100 | 47 | -53 (%) | 0.001 | |

| Avoidance/numbing | 100 | 24 | -76 (%) | < 0.001 | |

| Arousal | 100 | 68 | -32 (%) | 0.24 | |

| Grodin et al.13 | Qualitative Interview | Sleep problems | Decrease in: | ||

| Nightmares | Reexperiencing | ||||

| Flashbacks | Physical pain | ||||

| Decreased energy | Anxiety and stress | ||||

| Helplessness | Increase in: | ||||

| Hypervigilance | Equanimity | ||||

| Anxiety | Soothing effect | ||||

| Waelde et al.14 | PCL-S Total | 36.60 (9.97) | 30.57 (9.75) | -6.03 | < 0.01 |

| PCL-S subscales | |||||

| Reexperiencing | 8.79 (2.99) | 7.33 (2.53) | -1.46 | < 0.05 | |

| Avoidance | 14.99 (5.59) | 13.40 (4.21) | -1.59 | > 0.05 | |

| Hyperarousal | 12.74 (4.54) | 9.80 (3.84) | -2.94 | < 0.01 | |

| Brooks and Scarano28 | Post-Vietnam Stress Disorder | 9.70 (2.98) | 5.80 (4.26) | -3.90 | < 0.05 |

| Kimbrough et al.15 | PCL/PTSD Symptoms | 46.8 (2.7) | 32.3 (1.9) | -14.5 | < 0.0001 |

| Reexperiencing | 13.1 (1.0) | 10.0 (0.8) | -3.1 | < 0.001 | |

| Avoidance/numbing | 19.4 (1.0) | 13.0 (0.7) | -6.4 | < 0.001 | |

| Hyperarousal | 14.3 (1.0) | 9.5 (0.6) | -4.8 | < 0.001 | |

| Rosenthal et al.16 | CAPS/PTSD Symptoms | 71 | 39.6 | -31.4 | 0.02 |

| PCL-M | 57.8 | 33.8 | -24.0 | < 0.02 | |

| Kearney et al.17 | PCL-C total | 52.4 (16.3) | 41.9 (16.8) | -10.5 | < 0.001 |

| PCL-C subscales | |||||

| Reexperiencing | 14.2 (5.8) | 11.0 (5.3) | -3.2 | < 0.001 | |

| Avoidance | 5.7 (2.6) | 4.8 (2.5) | -0.9 | 0.003 | |

| Numbing | 15.7 (5.6) | 12.6 (5.5) | -3.1 | < 0.001 | |

| Hyperarousal | 16.9 (5.2) | 13.4 (5.3) | -3.5 | < 0.001 | |

Data are shown as mean (SD).

Abbreviations: PCL-17, PTSD Checklist; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; CPSS, Child PTSD Symptom Scale; HRV, Heart Rate Variability; LF, Low Frequency; HF, High Frequency; pNN50, the percentage of successive normal cardiac interbeat intervals greater than 50 msec; PTSD-I, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Interview; Rx, Relaxation; RxBr, Relaxation plus Breathing; RxBrTb, Relaxation plus Breathing and Thermal Biofeedback; IES, Impact of Event Scale; UPID, UCLA PTSD Index for DSM-IV; PTSD-RI, PTSD Reaction Index; HTQ, Harvard Trauma Questionnaire; Re, Reexperiencing; AN, Avoidance and Numbing; Ar, Arousal; PCL-S, PTSD Checklist-Specific Version; CAPS, the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; PCL-M, PTSD Checklist-Military Version; PCL-C, PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version.

Studies on PTSD Symptom Severity

Although there were several common elements in the reviewed studies, such as mindfulness, exercise, meditation, and deep breathing, the outcome parameter for assessing “changes in PTSD symptom severity” varied. The common measures of symptom severity were performed using self-rated instruments such as the PTSD CheckList (PCL), the Post-Vietnam Stress Disorder (PVSD), the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ), the Impact of Event Scale (IES), the UCLA PTSD Index for DSM-IV (UPID), the PTSD Reaction Index (PTSD-RI) and the Child PTSD Symptom Scale (CPSS). Of the 16 reviewed studies (Table 1), 3 studies showed no statistically significant outcomes,24-26 2 studies collected only qualitative data,27 and 11 studies showed a significant decrease of PTSD symptom severity as a result of participation in a mind-body interventions.7-12, 14-17, 28 In the 10 studies that incorporated follow-up testing ranging from 3 months to 15 months following intervention, positive results were maintained.7, 8, 10-17 Six studies reported decreases in specific PTSD symptom clusters including reexperiencing, avoidance and numbing, and hyperarousal.8, 10, 12, 14, 17, 24

The five RCTs shared common mindfulness-based components of relaxation, meditation, and deep breathing. Watson and colleagues24 compared relaxation, relaxation plus deep breathing, and relaxation plus deep breathing and thermal biofeedback. The authors reported pre-test PTSD Index scores of 95.4, 98.1, 90.5 and post-test PTSD Index scores of 95.0, 97.8, 89.4 for relaxation, relaxation plus deep breathing, and relaxation plus deep breathing and thermal biofeedback, respectively, but they found no significant difference between groups (p > 0.05) (Table 2). Conversely, Catani and colleagues10 found that a short-term meditation-relaxation intervention may reduce PTSD symptoms. The investigators randomized 31 children (mean age: 12 years) into meditation-relaxation (MED-RELAX) or Narrative Exposure Therapy (KIDNET) interventions one month after the Tsunami in the North-Eastern region of Sri Lanka. After 6 sessions conducted over a two week period, participation in the MED-RELAX program was associated with a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms (UPID scores of 36.58 and 12.59, pre- and posttest respectively, Cohen’s d = 1.83) (Table 2). More importantly, these results were as effective as the conventional KIDNET PTSD therapy (UPID scores of 37.94 and 12.41, pre- and posttest respectively, Cohen’s d = 1.76). Furthermore, the 6-month follow-up UPID scores were 9.75 (80% recovery rate) and 12.3 (70% recovery rate) for MED-RELAX and KIDNET respectively, demonstrating the long-term effectiveness of MED-RELAX.

A randomized non-controlled study conducted in 1981 on Vietnam veterans28 found a significant positive treatment effect for transcendental meditation in comparison with traditional psychotherapy on the symptoms of post-Vietnam stress disorder (F [1,14]) = 5.26, p < 0.05). This study also revealed a significant decrease in anxiety, depression, alcohol consumption, insomnia, and family problems in the meditation group. Rosenthal and collegues16 also reported that transcendental meditation had a significant positive impact on alleviating PTSD symptoms among veterans returning from Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom with combat-related PTSD. All subjects (n = 5) showed significant mean reductions in the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) and the PTSD Checklist-Military Version with decreases of 31.4 points (p = 0.02) and 24.00 points (p < 0.02), respectively. Similarly, the RCT conducted in 2008 by Gordon and colleagues12 showed decreases in PTSD symptoms in postwar Kosovar adolescents. The authors randomized 82 high school students into a 12-session mind-body skills program or a wait-list control group and measured the changes in PTSD symptoms using HTQ. The first 16-items of HTQ are widely used for assessment of PTSD and the cut-off score of 2.5 is generally considered positive for PTSD with the higher scores more likely to be symptomatic. The study has shown that the HTQ scores improved significantly (2.5 and 2.0, pre- and posttest, respectively, p < 0.001). These findings were consistent with the results from their previous pilot study in 2004 (Table 1). Furthermore, they reported that all three PTSD symptom clusters were significantly reduced after mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) intervention: re-experiencing (p = 0.001), avoidance and numbing (p < 0.001), and hyperarousal (p = 0.001).

Kearney and colleagues reported that 40% of veterans (n = 92) who practiced MBSR showed clinically significant reduction in PTSD symptom severity at two months, and symptom improvement was maintained at the 6-month follow-up. On the other hand, Staple and colleagues reported that individuals with higher baseline scores of symptom severity showed greater improvement in response to the mind-body skills intervention, but the gains did not entirely persist at follow-up. Branstrom and colleagues25 also found that an 8-week MBSR intervention did not have a significant impact on PTSD symptom reduction at 6-month follow-up among patients with a previous cancer diagnosis, but reported a significant reduction in avoidance symptoms.

A recent study reported a positive effect of repeating a mantram (i.e. - a sacred word or phrase) on PTSD symptoms. Bormann and colleagues9 conducted a 6-week randomized controlled trial (n = 136) with a portable practice of repeating a mantram among veterans with military trauma, and found a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms with mean PCL-C scores reduced from 61.8 at baseline to 55.3 at 6-week postintervention (p = 0.02). However, the results of the study did not reach a level of clinical significance suggesting that some mind-body interventions may best be considered as an adjunct to treatment as usual. Interestingly, Telles et al.26 conducted a yoga study in which the visual analog scales (VAS) were used to measure self-rated indicators of PTSD symptoms including fear, anxiety, disturbed sleep, and sadness. The VAS is an analog scale with a 10 centimeter long doubly anchored scale, with one end (score = 0) indicating the lowest intensity of a feeling of a symptom of PTSD and the other end (score = 10) of the scale indicating the highest intensity of a feeling of a symptom of PTSD. Using the Screening Questionnaire for Disaster Mental Health (SQD) which includes subscales on PTSD (9 items) and depression (6 items), the authors assessed 1,089 flood victims in Bihar, India, determined the scores for PTSD and depression 2 days before their study, and randomized 22 participants into a yoga group and a non-yoga wait-list control group. The mean baseline SQD scores of the 22 participants was 4.5 (SQD score of 9-6 = severely affected with possible PTSD, 5-4 = moderately affected, 3-0 = slightly affected with little possibility of PTSD). After seven days of yoga training, the yoga group showed a significant decrease in sadness (Mean ± SD: 7.12 ± 3.21 vs. 5.98 ± 3.58, p < 0.05), and the non-yoga group showed increased anxiety (Mean ± SD: 4.76 ± 2.69 vs. 4.88 ± 3.15, p < 0.05).

Studies on Vagal Activity

HRV is the cyclic beat-to-beat variation in heart rate generated by the interplay between sympathetic and parasympathetic neural activity at the sinus node of the heart.4 It is used as an index to measure changes in the autonomic nervous system,29 and is a reliable marker of vagal (parasympathetic) activity of the heart, as well as stress vulnerability.4, 30 In general, decreased HRV reflects increased sympathetic regulation and stress,31 and is associated with increased PTSD symptom severity.32 One study that examined the relationship between mind-body intervention and HRV during the stress response following a natural disaster showed no improvement in Heart Rate Variability among individuals with anxiety.26 After a month of natural disasters in north India, Telles et al. (2010) assessed 1,089 disaster victims using the Screening Questionnaire for Disaster Mental Health (SQD) to obtain scores for PTSD and depression.26 Twenty-two participants were randomized into yoga therapy or wait-list control groups. Researchers collected HRV data using frequency domain analysis for very low frequency (VLF) band (0.0-0.04 Hz), low frequency (LF) band (0.5-0.15 Hz), and high frequency (HF) band (0.15-0.50 Hz), as well as the LF/HF ratio (Table 2). They also recorded time domain HRV analysis using pNN50, the percentage of successive normal cardiac interbeat intervals greater than 50 msec.26 No significant changes were found in the HRV between the groups.

DISCUSSION

There is evidence that multiple components of mind-body practices provide beneficial therapeutic effects for relief of PTSD symptoms, as reflected in the reviewed studies.7-13, 24, 26 The observed therapeutic effects in clinical outcome measures were generally sustained at follow-up. Although one study raises a question regarding the strength of the conclusions that can be drawn from only 5 subjects without a control group,16 twelve out of the sixteen studies showed positive impacts of a mind-body approach and demonstrated significant improvements in PTSD symptom severity. Importantly, the broad range of geographic and demographic elements in the selected studies suggests that mind-body interventions are beneficial across a wide variety of populations.

Time and Age Factors for PTSD Treatment

It has been suggested that the total time spent in meditation practice is positively associated with greater improvement in PTSD symptom severity.14 These studies indicate that early intervention with mind-body practices may foster greater impacts on symptom management in PTSD, but this does not preclude the effective use of interventions at a later stage. However, in an adult population with 99% female PTSD patients, Branstrom and colleagues25 found that an 8-week MBSR intervention resulted in reduced avoidance symptoms, but not other symptom clusters, and that the effect was not maintained at 6-month follow-up. Although a number of studies have demonstrated that the amount of meditation practice is positively associated with a beneficial reduction in PTSD symptom severity, the finding by Branstrom et al. that the initial effect was not maintained may indicate that mindfulness alone might not be sufficient to induce a therapeutic effect but that persistent practice may be necessary. Another possible explanation is that the initial positive impact may have been due to something other than the effect of mindfulness (i.e., placebo effect or group support).

Age is also a factor that may affect the outcomes associated with mind-body intervention. One study showed that individuals with higher baseline scores showed greater improvements in PTSD; that higher baseline PTSD symptoms were correlated with the degree of previous trauma exposure but not with age; and that older children showed greater improvement in PTSD symptom reduction than younger children.8

In summary, it is likely that a longer duration of practice may have a greater impact in PTSD symptom reduction; that interventions should be prescribed based on individual trauma history, age, and gender; and that continued regular practice may be required for significant positive effects after the end of the program.

Parasympathetic Regulation

PTSD symptom severity is inversely associated with HRV and HRV is closely related to the rate of breathing.32 Fast breathing stimulates the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), while slow breathing activates the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS). Studies have suggested that yoga practice may stimulate the vagus nerves and increase PNS activity and HRV, which may be associated with reduction of PTSD symptoms.5 For example, yoga breathing practice has shown therapeutic effects on women who had been victims of abuse and intimate partner violence.33 One study we reviewed, however, did not find a significant effect of yoga practices on HRV. In that study,26 the absence of change in HRV may have been due to the nature of the exercise protocol which included a combination of fast and slow breathing. An intervention consisting only of slow breathing practice may have increased parasympathetic function and HRV.

Considering the circumstances in which the research was conducted, one month after the natural calamity of a monsoon in the north of India, it is presumable that one week of daily 1-hour yoga practice sessions may not have been sufficient to increase HRV. According to the author, some of the difficulties encountered during the study included the challenges of setting up a temporary laboratory, getting people to participate when they were preoccupied with their own concerns and in distress, and the constant influx and movement of the people in the disaster zone (personal communication).

Jerath and colleagues34 stated that deep breathing decreases oxygen consumption, heart rate, and blood pressure and increases parasympathetic activity, leading to a calming effect on the mind and a sense of control of the body. The authors proposed that voluntary slow deep breathing resets the autonomic nervous system and causes shifts in the autonomic equilibrium toward parasympathetic dominance, increasing the frequency and duration of inhibitory neural signals through activation of stretch receptors in the lungs during inhalation, and inducing hyperpolarization currents through the stretching of connective tissue, thereby synchronizing neural elements in the heart, lungs, limbic system and cortex.34 Further investigation regarding the effect of mind-body practices and deep breathing may clarify the relationship between the frequency and depth of breath and parasympathetic regulation.

Clinical Implications of Mind-body Interventions

Evidence presented in this review supports mind-body practices as an efficacious adjunct therapy for the treatment of PTSD. Mind-body practices may contribute to decreasing PTSD symptoms by offering participants opportunities to reduce stress levels, improve mood, reduce the intensity of PTSD arousal symptoms, and observe what they experience from a more relaxed state with less fear and more equanimity.8 In one of the earliest randomized comparisons between transcendental meditation and traditional psychotherapy researchers found that the meditation group reported significant reductions in numbness, anxiety, depression, insomnia, alcohol consumption, and family problems, while psychotherapy group participants reported little change.28

Individuals with PTSD increasingly use mind-body interventions as an alternative or adjunct to conventional care for PTSD. Clinicians should discuss mind-body interventions with their patients and educate them about the potential benefits of mind-body practices to maximize the diversity of treatment options.3 Knowledge of modalities of mind-body interventions, and of providers in the community who can direct mind-body intervention, may provide patients with the opportunity to explore individualized self-care therapies. Further studies are warranted to assess the comprehensive effects of mind-body practices as an adjunct to treatment as usual on managing comorbid diseases and improving quality of life in individuals suffering from PTSD.

Safety Matters

Although there may be physical and mental health risks associated with the use of mind-body practices for PTSD sufferers, adverse reactions may be minimized through the use of interventions that are culturally appropriate and that take into account other mental health conditions.35 Additionally, physical injuries or the presence of cardiopulmonary disease may present a barrier to participation in trauma survivors.36 Finally, there is evidence of the potential increased levels of anxiety associated with relaxation therapy: intrusive thoughts (15%), fear of losing control (9%), muscle cramps (4%), and disturbing sensory experiences (e.g., sexual arousal linked to the therapist; 4%) lead to noncompliance or termination of treatment by up to 3% of clients.37 Potential barriers to compliance can be mitigated by individualizing interventions, communicating openly with the participant regarding needs and expectations36, and adapting therapy programs to the unique responses of the individual patient.38

Limitations

The research methodologies included in this review were heterogeneous, and the quality of the studies varied widely. Due to differences in design, intervention methods, and study duration, as well as the presence or absence of control groups, we were unable to conduct a true meta-analysis. The studies by Gordin and colleagues13 and Stankovic27 were the only qualitative research studies included in this review. Despite the lack of quantitative outcomes, we included the studies because of the long study duration (>1 yr) and the detailed descriptions of the study outcomes. Most of the studies we reviewed for potential inclusion in the study did not have a control group, and two of the reviewed articles had a large amount of missing data.8 Attrition was problematic in one study, with 31 percent of the study participants dropping out after baseline data were collected.7 Additionally, the mean ages of study participants ranged from 12 to 56 years in the reviewed studies, with predominantly male subjects or a mixture of both genders. Future studies need to include younger or older populations to examine whether efficacy may be generalized to those groups, and particularly to female subjects.

Conclusions

Future studies need to replicate these findings in other cultural settings with varied populations, preferably with larger samples and additional outcome measures such as biomarkers (i.e., cortisol, adrenocorticotropic hormones, epinephrine, norepinephrine, stress-related neuropeptides, and cytokines). Elucidation of the relationships between changes in psychological symptoms and changes in the biomarkers, as well as the pathways activated by specific mind-body modalities, will advance our understanding of the nonpharmacologic psycho-biological mechanism(s) of mind-body practices for clinical application. The insights gained from such integrated research could further our knowledge and enable us to develop comprehensively therapeutic yet individually specific treatment strategies which, together with other lifestyle modifications and psychotherapies, will become a part of the standard treatment regimen for PTSD in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ingrid Hendrix, the Nursing Services Librarian at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Library and Informatics Center, for assisting in identifying the literature.

Funding Support: 5KL2RR031976-02, 5UL1RR031977-02

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV-R. 4. Washington DC: 2000. Revised. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute of Mental Health. [March 6, 2011];The Numbers Count: Mental Disorders in America. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/site-info/contact-nimh.shtml.

- 3.Libby DJ, Pilver CE, Desai R. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Individuals With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Psychological Trauma:Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a002708. Advance online publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blechert J, Michael T, Grossman P, Lajtman M, Wilhelm FH. Autonomic and respiratory characteristics of posttraumatic stress disorder and panic disorder. Psychosom Med. 2007 Dec;69(9):935–943. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815a8f6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Streeter CC, Gerbarg PL, Saper RB, Ciraulo DA, Brown RP. Effects of yoga on the autonomic nervous system, gamma-aminobutyric-acid, and allostasis in epilepsy, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Med Hypotheses. 2012 Feb 24; doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cukor J, Spitalnick J, Difede J, Rizzo A, Rothbaum BO. Emerging treatments for PTSD. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009 Dec;29(8):715–726. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Descilo T, Vedamurtachar A, Gerbarg PL, et al. Effects of a yoga breath intervention alone and in combination with an exposure therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder and depression in survivors of the 2004 South-East Asia tsunami. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010 Apr;121(4):289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Staples JK, Abdel Atti JA, Gordon JS. Mind-body skills groups for posttraumatic stress disorder and depression symptoms in Palestinian children and adolescents in Gaza. International Journal of Stress Management. 2011;18(3):246–262. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bormann JE, Liu L, Thorp SR, Lang AJ. Spiritual Wellbeing Mediates PTSD Change in Veterans with Military-Related PTSD. Int J Behav Med. 2011 Aug 28; doi: 10.1007/s12529-011-9186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catani C, Kohiladevy M, Ruf M, Schauer E, Elbert T, Neuner F. Treating children traumatized by war and Tsunami: A comparison between exposure therapy and meditation-relaxation in North-East Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon JS, Staples JK, Blyta A, Bytyqi M. Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Postwar Kosovo High School Students Using Mind–Body Skills Groups: A Pilot Study. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17(12):143–147. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000022620.13209.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon JS, Staples JK, Blyta A, Bytyqi M, Wilson AT. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in postwar Kosovar adolescents using mind-body skills groups: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008 Sep;69(9):1469–1476. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grodin MA, Piwowarczyk L, Fulker D, Bazazi AR, Saper RB. Treating survivors of torture and refugee trauma: a preliminary case series using qigong and t’ai chi. J Altern Complement Med. 2008 Sep;14(7):801–806. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waelde LC, Uddo M, Marquett R, et al. A pilot study of meditation for mental health workers following Hurricane Katrina. J Trauma Stress. 2008 Oct;21(5):497–500. doi: 10.1002/jts.20365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimbrough E, Magyari T, Langenberg P, Chesney M, Berman B. Mindfulness intervention for child abuse survivors. J Clin Psychol. 2010 Jan;66(1):17–33. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenthal JZ, Grosswald S, Ross R, Rosenthal N. Effects of transcendental meditation in veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom with posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot study. Mil Med. 2011 Jun;176(6):626–630. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-10-00254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kearney DJ, McDermott K, Malte C, Martinez M, Simpson TL. Association of participation in a mindfulness program with measures of PTSD, depression and quality of life in a veteran sample. J Clin Psychol. 2012 Jan;68(1):101–116. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Streeter CC, Gerbarg PL, Saper RB, Ciraulo DA, Brown RP. Effects of yoga on the autonomic nervous system, gamma-aminobutyric-acid, and allostasis in epilepsy, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Med Hypotheses. 2012 May;78(5):571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown RP, Gerbarg PL. Yoga breathing, meditation, and longevity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009 Aug;1172:54–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernardi L, Gabutti A, Porta C, Spicuzza L. Slow breathing reduces chemoreflex response to hypoxia and hypercapnia, and increases baroreflex sensitivity. J Hypertens. 2001 Dec;19(12):2221–2229. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200112000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaiva G, Thomas P, Ducrocq F, et al. Low posttrauma GABA plasma levels as a predictive factor in the development of acute posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2004 Feb 1;55(3):250–254. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McEwen BS. Allostasis and allostatic load: implications for neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000 Feb;22(2):108–124. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.NCCAM. [July 5, 2012];What is Complementary and Alternative Medicine? http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam.

- 24.Watson CG, Tuorila JR, Vickers KS, Gearhart LP, Mendez CM. The efficacies of three relaxation regimens in the treatment of PTSD in Vietnam War veterans. J Clin Psychol. 1997 Dec;53(8):917–923. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199712)53:8<917::aid-jclp17>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Branstrom R, Kvillemo P, Moskowitz JT. A Randomized Study of the Effects of Mindfulness Training on Psychological Well-being and Symptoms of Stress in Patients Treated for Cancer at 6-month Follow-up. Int J Behav Med. 2011 Sep 20; doi: 10.1007/s12529-011-9192-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Telles S, Singh N, Joshi M, Balkrishna A. Post traumatic stress symptoms and heart rate variability in Bihar flood survivors following yoga: a randomized controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stankovic L. Transforming trauma: a qualitative feasibility study of integrative restoration (iRest) yoga Nidra on combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Int J Yoga Therap. 2011;21:23–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brooks JS, Scarano T. Transcendental Meditation in the Treatment of Post-Vietnam Adjustment. Journal of Counseling & Development. 1985;64(3):212–215. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song BA, Yoo SY, Kang HY, et al. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Depression, and Heart-Rate Variability among North Korean Defectors. Psychiatry Investig. 2011 Dec;8(4):297–304. doi: 10.4306/pi.2011.8.4.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porges SW. Cardiac vagal tone: a physiological index of stress. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1995 Summer;19(2):225–233. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)00066-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dishman RK, Nakamura Y, Garcia ME, Thompson RW, Dunn AL, Blair SN. Heart rate variability, trait anxiety, and perceived stress among physically fit men and women. Int J Psychophysiol. 2000 Aug;37(2):121–133. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(00)00085-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen H, Kotler M, Matar MA, et al. Analysis of heart rate variability in posttraumatic stress disorder patients in response to a trauma-related reminder. Biol Psychiatry. 1998 Nov 15;44(10):1054–1059. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00475-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franzblau SH, Echevarria S, Smith M, Van Cantfort TE. A preliminary investigation of the effects of giving testimony and learning yogic breathing techniques on battered women’s feelings of depression. J Interpers Violence. 2008 Dec;23(12):1800–1808. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jerath R, Edry JW, Barnes VA, Jerath V. Physiology of long pranayamic breathing: neural respiratory elements may provide a mechanism that explains how slow deep breathing shifts the autonomic nervous system. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67(3):566–571. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerbarg PL, Wallace G, Brown RP. Mass disasters and mind-body solutions: evidence and field insights. Int J Yoga Therap. 2011;(21):97–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim SH, Kravitz L, Scheneider SM. PTSD & Exercise: What Every Exercise Professional Should Know. IDEA Fitness Journal. 2012 Jun;9:20–23. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edinger JD, Jacobsen R. Incidence and significance of relaxation treatment side effects. Behav Ther. 1982;5:137–138. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carlson CR, Nitz AJ. Negative side effects of self-regulation training: relaxation and the role of the professional in service delivery. Biofeedback Self Regul. 1991 Jun;16(2):191–197. doi: 10.1007/BF01000193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]