Abstract

The Hedgehog (Hh) pathway was first defined by its role in segment polarity in the Drosophila melanogaster embryonic epidermis and has since been linked to many aspects of vertebrate development and disease. In humans, mutation of the Patched1 (PTCH1) gene, which encodes an inhibitor of Hh signaling, lead to tumors of the skin and pediatric brain. Despite the high level of conservation between the vertebrate and invertebrate Hh pathways, studies in Drosophila have yet to find direct evidence that ptc limits organ size. Here we report identification of Drosophila ptc in a screen for mutations that require a synergistic apoptotic block in order to drive overgrowth. Developing imaginal discs containing clones of ptc mutant cells immortalized by the concurrent loss of the Apaf-1-related killer (Ark) gene are overgrown due, in large part, to the overgrowth of wild type portions of these discs. This phenotype correlates with overexpression of the morphogen Dpp in ptc,Ark double-mutant cells, leading to elevated phosphorylation of the Dpp pathway effector Mad (p-Mad) in cells surrounding ptc,Ark mutant clones. p-Mad functions with the Hippo pathway oncoprotein Yorkie (Yki) to induce expression of the pro-growth/anti-apoptotic microRNA bantam. Accordingly, Yki activity is elevated among wild type cells surrounding ptc,Ark clones and alleles of bantam and yki dominantly suppress the enlarged-disc phenotype produced by loss of ptc. These data suggest that ptc can regulate Yki in a non-cell autonomous manner and reveal an intercellular link between the Hh and Hippo pathways that may contribute to growth-regulatory properties of the Hh pathway in development and disease.

Keywords: Patched, Hedgehog, Apoptosis, Yorkie, Growth, Drosophila

Introduction

Genetic screens in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster have identified a number of genes that are required to restrict the growth of developing tissues (reviewed in (Hariharan and Bilder, 2006; Pan, 2007)). A number of these genes control the process of tissue growth by regulating largely cell-intrinsic mechanisms that modulate rates of cell division, death, or growth. However, other genes exhibit more complex phenotypes indicative of roles in intercellular signaling and morphogen-based pathways that pattern the growth and differentiation of groups of cells in developing organs. Vertebrate orthologs of both classes of Drosophila anti-growth genes are mutated inhuman disease and collaborate with anti-apoptotic mutations to drive cancer e.g. (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011; Vidal and Cagan, 2006). Similar synergy occurs in Drosophila (Asano et al., 1996; Herz et al., 2006; Nicholson et al., 2009; Staehling-Hampton et al., 1999) and has been used to identify ‘conditional’ pro-growth mutations that require a collaborating block in cell death to drive tissue overgrowth (Gilbert et al., 2011).

The Hedgehog (Hh) pathway was first defined by its role in segment polarity in the Drosophila embryonic epidermis (Nusslein-Volhard and Wieschaus, 1980) and has since been linked to many aspects of vertebrate development and disease (Bale, 2002), including cancer (Jiang and Hui, 2008). Core Hh pathway components include the secreted morphogen Hh, a receptor complex composed of the transmembrane proteins Patched (Ptc) and Smoothened (Smo), the intracellular signaling components Protein Kinase A (PKA) and Costal-2 (Cos2), and the nuclear transcription factor Cubitus interruptus (Ci; Gli in vertebrates) (Jiang and Hui, 2008). Canonical signaling involves binding of Hh to Ptc, which relieves Ptc inhibition of the G-protein-coupled receptor Smo and allows Smo to signal via PKA/Cos2 to stimulate cleavage of Ci, which converts it from a transcriptional repressor to a transcriptional activator. In humans, loss-of-function mutations in Patched1 (PTCH1) occur in 90% of sporadic basal cell carcinoma (BCC) cases and in a significant subset of pediatric medulloblastomas (Corcoran and Scott, 2001). As loss of PTCH1/Ptc activates Gli/Ci, this mutational data suggests that ectopic Ci/Gli activity promotes carcinogenesis in vivo and this model is supported by the original identification of the human Gli gene as a locus amplified in glioblastomas (Kinzler et al., 1987). This model is further supported by elevated rates of tumorigenesis in mice that either lack the murine PTCH1 homolog or overexpress Smo protein (Hahn et al., 1999).

Despite the high level of conservation between the vertebrate and invertebrate Hh pathways (Huangfu and Anderson, 2006), genetic analyses of the developmental effects of ptc loss in Drosophila have yet to show evidence of a direct role in suppressing tissue growth. ptc mutant cells in the Drosophila larval imaginal discs, a commonly used model of invertebrate growth control (for review see (Hariharan and Bilder, 2006)), undergo apoptotic cell death (Thomas and Ingham, 2003) and show deregulated expression of Ci target genes involved in developmental patterning, including the morphogens decapentaplegic (dpp) and wingless (wg), the segment polarity gene engrailed (en), and the ptc gene itself as part of a negative feedback mechanism (Bale, 2002). Additionally Ptc has been suggested to autonomously promote, rather than restrict, cell proliferation in the developing head capsule (Shyamala and Bhat, 2002). Cells in the Drosophila eye imaginal disc located just anterior to the morphogenetic furrow (MF) respond to ptc loss by elevating expression of G1 cyclins (Cyclin E and Cyclin D) and Ci protein interacts with the promoters of these genes in cultured Drosophila S2 cells (Duman-Scheel et al., 2002). However, the link between Ptc and G1 cyclin gene expression is spatially and temporally restricted within the developing eye and has not been shown to affect overall rates of tissue growth.

Here we report the identification of the ptc gene in a screen for Drosophila mutations that require a collaborating block in cell death to increase imaginal disc size. As reported previously (Thomas and Ingham, 2003) ptc mutant disc cells survive poorly into adulthood, however those lacking both ptc and the pro-apoptotic gene Apaf-1-related killer (Ark) (Kanuka et al., 1999; Rodriguez et al., 1999; Zhou et al., 1999) survive and drive substantial overgrowth of both mutant tissue and surrounding wild type tissue. ptc,Ark mutant cells express elevated levels of the Ci target gene dpp and produce a gradient of Dpp signaling extending out from ptc mutant cells into surrounding wild type tissue. This Dpp gradient is coincident with activation of Yorkie (Yki), a transcriptional cofactor that acts as the primary nuclear effector of the Salvador/Warts/ Hippo (SWH) tumor suppressor pathway (reviewed in (Pan, 2010)). Yki has been shown to promote growth in response to Dpp gradients in the larval wing (Rogulja et al., 2008) and interacts with the Dpp responsive transcription factor Mad to promote expression of the bantam microRNA (Oh and Irvine, 2011). Accordingly, alleles of bantam or yorkie suppress disc growth associated with ptc loss, confirming a model in which ptc is required to restrict Yki activity. Increased levels of the Yki homolog Yap1 in PTCH1−/− medulloblastoma cells (Fernandez et al., 2009) may provide a human correlate to this Ptc/Yki link in Drosophila. In sum these data provide insight into an intercellular link between Ptc and Yki activity in fly imaginal discs that may be significant to the growth-regulatory properties of the Hh pathway in disease. Given the emerging role of the SWH pathway in human cancers, the ptc/Ark genotype could serve as a useful model of tumor/stromal interactions in cancers in which Hh signaling is altered such as BCC and medulloblastoma.

Methods

Genetics

The Ark82 (Akdemir et al., 2006) loss-of-function allele was used as the basis for the EMS screen. Briefly, w;FRT42D,Ark82 males were fed EMS and mated to eyeless>Flp;FRT42D virgins. Mosaic eyes of F2 adult flies were examined for evidence of deregulated growth, which was identified by an over-representation of pigmented mutant tissue, an increase in overall organ size, or both. Over 5,000 F2 flies were screened, and stable stocks were generated for 137 mutants. One of these mapped to the patched locus and was designated ptcB.2.13. Additional genotypes used: thread-lacZ (Th-Z) (Hay et al., 1995), expanded-lacZ (Ex-Z) (Boedigheimer et al., 1993), bantam-GFP (ban-GFP) (Brennecke et al., 2003), bantamz Δ1 (Hipfner et al., 2002), dad-lacZ (Dad-Z) (Tsuneizumi et al., 1997), UAS-ptc-IR (TRiP), UAS-dpp (Bloomington), and ykiB5 (Huang et al., 2005).

Immunohistochemistry

Unless otherwise noted, immunostaining and confocal imaging were performed using standard techniques. Briefly, eye and wing discs were dissected from wandering third instar larvae, fixed on ice in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.3% PBST, and incubated in 0.1% PBST+10% Normal Goat Serum (NGS) and appropriate antibody dilution. For analysis of ban-GFP expression wing discs were dissected, fixed overnight in 0.75% paraformaldehyde and 0.01% Tween, then permeabilized in 0.3% PBST. Antibodies from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB): anti-Ptc (mouse, 1:40), anti-Wg (mouse, 1:800), anti-Elav (rat, 1:800), and anti-Ci (rat, 1:100). Other antibodies: anti-ß galactosidase (mouse, 1:1000, Promega), anti-phospho-Smad1/5 (rabbit, 1:100, Cell Signaling), anti-DIAP (mouse, 1:50)(Yoo et al., 2002), anti-Caspase3 (rabbit, 1:100, Cell Signaling), anti-Dpp (rabbit, 1:100)(Gibson et al., 2002), anti-GFP (chicken, 1:100, Aves Labs) and Alexa-594 Phalloidin (1:50, Molecular Probes).

BrdU incorporation was adapted from Pellock, et. al. (Pellock et al., 2007). Briefly, wing discs were dissected in Schneider's serum-free media and labeled in 100μM BrdU with gentle agitation for 30 minutes. Discs were then fixed overnight in 0.75% paraformaldehyde and 0.01% Tween, treated with DNase (Promega), permeabilized in 0.3% PBST for 10 minutes, and immunostained in 0.1% PBST+10% NGS and 1:50 of anti-BrdU (mouse, DSHB).

Results

Patched is a conditional suppressor of growth

The ey>Flp/FRT system was used to perform an EMS mutagenesis screen of Drosophila chromosome 2R for mutations that altered eye development. The parental FRT42D chromosome also carried a mutant allele of the Apaf-related killer (Ark) gene, Ark82 (Akdemir et al., 2006)). Ark is a homolog of the vertebrate pro-apoptotic gene Apaf-1 and is required for most programmed cell death in Drosophila (Mills et al., 2006). The Ark82 allele is null produced by imprecise excision of the P{lacW}ArkCD4 element; it retains the w(m+) element and thus can be tracked in adult eyes by the presence of red pigment. FRT42D,Ark82 mosaic eyes also show little evidence of effects on growth or patterning (Figure 1A), consistent with evidence that a block in apoptosis is insufficient to overtly alter eye or head size e.g. (Du et al., 1996)(Gilbert et al., 2011).

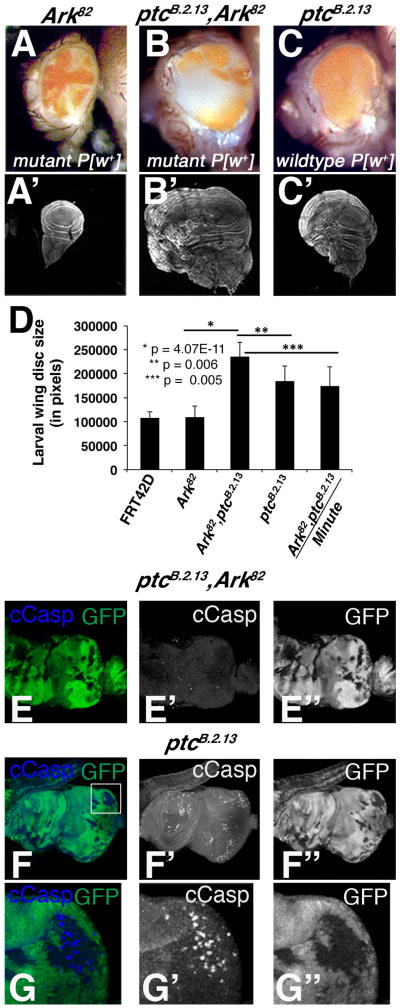

Figure 1. A mosaic screen for conditional suppressors of growth identifies a novel allele of patched, ptcB.2.13, as a conditional suppressor of growth.

Mosaic adult eyes and imaginal wing discs from L3 larvae, stained with phalloidin: (A-A′) Ark82 (mutant tissue is pigmented) (B-B′) ptcB.2.13,Ark82 (mutant tissue is pigmented) (C-C′) ptcB.2.13 (wild type tissue is pigmented);(D) Quantification of mosaic wing discs size from L3 larvae demonstrates the condional nature of the ptcB.2.13,Ark82 overgrowth; Mosaic larval eye discs stained with anti-Cleaved Caspase 3 (cCasp) shows ptcB.2.13mutant clones accumulate cCasp without Ark82(E-E″) ptcB.2.13,Ark82 (mutant tissue is GFP negative)(F-G″) ptcB.2.13(inset is amplified in G-G″)(mutant tissue is GFP negative).

The FRT42D,Ark82 EMS screen identified 137 mutants with mild to severe growth defects (data not shown). A number of these alleles appeared to affect genes required for autonomous survival and non-cell autonomous growth suppression. One of these mutants, which showed strong overgrowth of wild type tissue relative to control red:white ratio in FRT42D,Ark82 control eyes (Figure 1A vs. 1B; note that mutant tissue is pigmented due to the P[m-w+] Ark82 allele), was mapped by deficiency complementation to genomic interval 44D. This allele failed to complement existing alleles of the ptc gene, which is located in this region, and was designated ptcB.2.13. In the absence of the Ark82 mutation, FRT42D,ptcB.2.13 mosaic eyes are irregular, composed of entirely pigmented, wild type tissue (Figure 1C; wild type tissue is pigmented due to presence of the P[m-w+] marked FRT42D,ubi>GFP tester chromosome), and only slightly enlarged. FRT42D,ptcB.2.13 clones accumulate cleaved caspase posterior to the morphogenetic furrow (MF) (Figure 1F-G) suggesting that ptc mutant cells located in this region undergo apoptosis, while ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mosaic discs showed no evidence of cleaved caspase accumulation (Figure 1E). Previous studies have documented a similar increase in apoptosis among of ptc mutant cells in the eye imaginal disc (Thomas and Ingham, 2003).

To assess whether the link between ptc/Ark loss and tissue growth is generalized to other epithelial tissues, the Ubx>Flp driver was used to create ptcB.2.13,Ark82 clones in the larval wing disc. This produced dramatically enlarged 3rd instar larval wing discs (Figure 1B′ vs. FRT42D,Ark82 control in Figure 1A′) and led to pupal lethality. Reintroduction of the wild type Ark allele into the ptcB.2.13 background suppressed this enlarged-disc phenotype (Figure 1C′) and partially suppressed pupal lethality (data not shown), thus confirming the conditional nature of the ptc overgrowth phenotype. These differences in larval wing were quantified and found to be highly significant (Figure 1D). Furthermore, the creation of a larval wing disc entirely mutant for ptcB.2.13,Ark82 (by flipping against a cell-lethal Minute allele) reduced wing disc size (Figure 1D), indicating that presence of wild type tissue enhances the ptcB.2.13,Ark82 overgrowth phenotype. In sum these data suggest that ptc loss cooperates with the block in apoptosis provided by the Ark82 allele to drive both autonomous and non-cell autonomous over-growth in the eye and wing.

ptc,Ark mutant tissue leads to an increase in cellular proliferation

Due to the premature differentiation and subsequent mitotic arrest of ptcB.2.13,Ark82 eye clones (Supplemental Figure 1), the wing disc was chosen as a system to investigate the molecular effect of ptcB.2.13,Ark82 clones on cell division in a proliferating epithelium. The ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mosaic wing discs show elevated incorporation of the S-phase marker BrdU and the mitotic marker phospho-Histone 3 (pH3) particularly in the anterior portion of the wing disc (Figure 2A-B), compared to discs carrying FRT42D,Ark82 clones, which show a more uniform pattern of BrdU incorporation and pH3 staining (Figure 2C-D). These increased proliferation markers are not restricted to ptcB.2.13,Ark82 clones but also occur in surrounding wild type tissue (see arrows, Figure 2A-B). The effect of ptcB.2.13,Ark82 clones on patterns of cell division coupled with the requirement for wild type tissue in maximal overgrowth of ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mosaic wing discs (Figure 1D) suggests that there may be a non-cell autonomous component to the ptcB.2.13,Ark82 disc-size phenotype. To test this hypothesis quantitatively, the percentage of mutant (non-GFP positive) and wild type (GFP positive) tissue was measured in wandering third instar wing discs carrying either Ark mutant clones, ptc mutant clones or Ark,ptc double mutant clones (all generated with the same UbxFLP transgene). On average, control Ark82 mosaic wing discs are composed of ∼38% mutant tissue (this percentage is likely the result of ‘unflipped’ heterozygous tissue), and ptcB.2.13 mosaic wing discs are comprised of only ∼20% mutant tissue, presumably from the apoptosis occurring within these cells. Although ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mosaic discs are approximately twice the size of Ark8 2 mosaic discs (see Figure 1D), they are nonetheless composed of only ∼32% mutant tissue (Figure 2E). Thus while ptcB.2.13,Ark82 discs are dramatically enlarged, the mutant portion of these discs is decreased relative to controls, indicating that the ptcB.2.13,Ark82 disc enlargement phenotype has a significant non-cell autonomous component.

Figure 2. ptcB.2.13,Ark82 wing discs have increased proliferation in both mutant cells and adjacent wild type cells.

Imaginal mosaic wing discs dissected from wandering L3 larvae stained with the proliferation markers BrdU and phospho-histoneH3 (pH3) in the anterior of the wing disc; ptcB.2.13,Ark82 (A-A″) stained with BrdU, see arrows for examples of non-autonomous increased proliferation (B-B″) stained with pH3, see arrow for example of non-autonomous increased proliferation; Ark82 (C-C″) stained with BrdU (D-D″) stained with pH3; (E) quantification of the portion of larval wing discs composed of mutant tissue reveals a non-autonomous component of ptcB.2.13,Ark82 overgrowth. Mutant tissue is GFP negative.

ptcB.2.13,Ark82 clones have increased levels of canonical Hh signaling

The cleaved form of the Ci transcription factor is typically expressed in the anterior domain of the wing disc, with highest levels immediately adjacent to the anterior:posterior (A:P) boundary (Motzny and Holmgren, 1995). This pattern of expression is unperturbed in Ark82 mosaic wing discs (Figure 3D). Additionally, two transcriptional targets of Ci, the Dpp and Ptcproteins are also unaltered in the Ark82 mosaic discs (Figure 3E and 3F) By contrast, ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mutant clones show a substantial increase in active Ci levels (Figure3A) and expression of Dpp and Ptc (Figure 3B and 3C). Similar effects on Hh signaling are observed in ptcB.2.13 clones in the anterior compartment, suggesting that the ptcB.2.13 mutation is sufficient for this phenotype (Supplemental Figure 2A). The ptcB.2.13 allele is thus similar to the ptcS2 allele, which functionally inactivates Ptc but remains responsive to induction by Ci (Methot and Basler, 2001). The induction of active Ci and elevation in levels of Ptc, and Dpp are restricted to ptcB.2.13,Ark82 clones located in the anterior domain of the wing disc (Figure 3A-C). Tracing the location of the A:P boundary reveals that the overgrowth of ptcB.2.13,Ark82 wing discs is due to enlargement of the size of the anterior domain, and this corresponds to the location of the elevated BrdU incorporation and pH3 staining (Figure 2A-B). Evidence of domain-specific enlargement is also evident in the phalloidin stains of ptcB.2.13,Ark82 wing discs, based on morphology of overgrown wing discs and A:P staining in Figure 3 (Figure 1B′).

Figure 3. mutant tissue has an autonomous increase in canonical Hedgehog signaling.

ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mosaic wing discs have a strong autonomous increase in Hedgehog signaling confined to the anterior portion of wing discs as demonstrated by (A-A‴) anti-Cubitus Interruptus (Ci), (B-B‴) anti-Patched (Ptc), (C-C‴) anti-Decapentaplegic (Dpp). The phenotype is dependent on ptcB.2.13, as Ark82 mosaic wing discs have normal Hedgehog signaling as demonstrated by (D-D″) Ci, (E-E″) Ptc, (F-F″) Dpp. Mutant tissue is GFP negative.

ptcB.2.13,Ark82 clones can activate Dpp signaling in adjacent wild cells

A gradient of Dpp signaling across the A:P axis of the wing disc promotes physiologic growth of that organ, and manipulations of this gradient can enhance growth (Rogulja et al., 2008; Schwank et al., 2008; Schwank et al., 2011). Consequently, the effects of ptcB.2.13,Ark82 clones on Dpp expression and wing growth prompted analysis of Dpp signaling in ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mosaic discs. Binding of Dpp to the transmembrane receptors Punt and Thickveins results in activation of the transcription factor Mothers Against Decapentaplegic (Mad) via phosphorylation (p-Mad1/5) (Letsou et al., 1995; Sekelsky et al., 1995). p-Mad1/5 levels are elevated in the anterior portion of ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mosaic wing discs as compared to control discs (Figure 4A-B vs 4D). Elevated p-Mad1/5 occurs within mutant clones, but the highest levels of p-Mad1/5 are found in wild type cells immediately adjacent to mutant clones, with a declining gradient of p-Mad1/5 activation extending multiple cell diameters into wild type tissue (see arrow, Figure 4A). To better visualize this non-autonomous activation we co-stained ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mosaic discs with anti-Ptc to mark the mutant clones, and with anti-pMad1/5 to visualize the Dpp activity gradient (see arrow, Figure 4B). A halo of p-Mad1/5 activation can be seen ringing Ptc-positive mutant clones, and a similar effect is detected in discs mosaic for ptcB.2.13 alone (Supplemental Figure 2B). To assess why ptcB.2.13,Ark82 cells within mutant clones, which are presumably exposed to the high levels of Dpp, do not exhibit the highest level of p-Mad1/5, we investigated expression of the inhibitory Mad family member, Daughters against decapentaplegic (Dad), through use of the transcriptional reporter Dad-lacZ (Tsuneizumi et al., 1997). Dad is induced by Dpp signaling in a negative feedback loop (Inoue et al., 1998) and is expressed in a domain along the anterior/posterior axis (Tsuneizumi et al., 1997). While Ark82 control clones have no effect on this pattern (Figure 4E), Dad-lacZ expression is ectopically elevated within ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mutant clones, but not in immediately adjacent wild type tissue where pMad1/5 are highest (see arrows, Figure 4C). This autonomous increase in Dad expression may explain why the highest levels of pMad1/5 are found in areas adjacent to ptcB.2.13,Ark82 clones where cells are closely apposed to a source of Dpp but do not express the Mad inhibitor Dad.

Figure 4. ptcB.2.13,Ark82 clones activate Dpp signaling most robustly in wild type cells immediately adjacent to mutant clones.

ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mosaic wing discs have an increase of Dpp signaling within the anterior of the wing disc, the signaling is highest in those cells immediately adjacent to mutant clones. Increases in Dpp signaling in ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mosaic discs measured by levels of phosphorylated-Mothers Against Decapentaplegic (p-Mad1/5) as marked by (A-A″) anti-p-Mad1/5 (p-Mad1/5) see arrows, (B-B″) Ptc denotes mutant clones (Figure 3B) and pMad1/5 levels create a ring round the mutant clones, see arrow; these same mutant discs have an autonomous increase in the inhibitory smad, Daughters Against Decapentaplegic (Dad) (C-C″) measured by the Dad transcriptional reporter Dad-LacZ (Dad-Z), see arrow; these phenotypes are dependent upon ptcB.2.13, as mosaic discs for Ark82 have normal pattern of (D-D″) p-Mad1/5 and (E-E″) Dad-Z. Mutant tissue is GFP negative, unless otherwise noted.

ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mosaic wing discs show elevated Yki activity

Drosophila and vertebrate Mad proteins physically interact with the corresponding SWH effector proteins Yki/Yap to alter nuclear gene expression (Alarcon et al., 2009; Oh and Irvine, 2011). Furthermore, the regulation of Yki through the Fat atypical cadherin is linked to the A:P gradient of Dpp in the wing (Rogulja et al., 2008). We therefore hypothesized that exposure of wing disc cells to the ectopic gradients of Dpp around ptcB.2.13,Ark82 clones could result in elevated Yki activity. To test the relationship between ptc loss and Yki activity, several well-characterized reporters of Yki activity including the enhancer trap ex-lacZ (ex697; (Boedigheimer et al., 1993)), the apoptosis inhibitor protein DIAP-1, and the bantam (ban) reporter, ban-GFP (Brennecke et al., 2003) were analyzed in ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mosaic wing discs. Similar to the expression pattern of pMad1/5, we find that DIAP1 levels are increased in wild type cells along the boundaries of ptcB.2.13,Ark82 clones within the anterior portion of the wing disc (see arrow, Figures 5A). A similar effect is observed in discs co-stained for Ci protein (to mark ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mutant cells) and DIAP1 (Figure 5B, see arrow). ex-lacZ is also elevated around ptcB.2.13,Ark82 clones (see inset, Figure 5C-D). Decreased ban-GFP, which correlates with elevated Yki activity, is also apparent in wild types cells outside of ptcB.2.13,Ark82 clones (see arrows, Figure 5E). These alterations in Yki targets are not seen in Ark82 mosaic discs (Figure 5G-I).The pattern of Yki target activation in ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mosaic discs correlates spatially with the p-Mad1/5 gradient (Figure 4A,B) suggesting that cells located along the steepest part of the Dpp gradient activate Yki most strongly, as has been proposed previously (Rogulja et al., 2008). Notably, levels and patterns of the protein Wingless (Wg) appear similar in ptcB.2.13,Ark82 and Ark82 control discs (Figure 5F and 5I), indicating that not all downstream readouts of Yki activity are affected by proximity to ptc mutant cells.

Figure 5. ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mutant clones result in gradient dependent activation of a subset of Yorkie target genes, which necessary for the ptcB.2.13,Ark82 overgrowth phenotype.

ptcB.2.13,Ark82 larval mosaic wing discs have elevated Yki activity in the anterior portion of the wing discs, with the highest levels occurring in wild type cells immediately adjacent to mutant clones. Increases of several Yki targets were elevated within ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mutant clones and in those wild type cells adjacent to the clones (A-A″) anti-Drosophila Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein 1 (DIAP1), see arrow, (B-B″) Ci denotes mutant clones (Figure 3B) and DIAP1 levels are most elevated just outside the mutant clones, see arrow, (C-C″) Expanded levels as measured by the reporter Expanded-lacZ (Ex-Z), (D-D″) Enlarged image of inset from 5C of Ex-Z, (E-E″) Ci denotes mutant clones and bantam levels are highest immediately adjacent to mutant clones as see by decreasing levels of the bantam reporter, ban-GFP. Not all Yki targets are altered by ptcB.2.13,Ark82 as Wingless pattern and levels are unchanged (F-F″) anti-Wingless (Wg). The alteration of Yki targets is dependent on the ptcB.2.13 mutation given that we find no alteration of Yki reporters in wing discs mosaic for Ark82, (G-G″) DIAP1, (H-H″)Ex-Z, (I-I″) Wg. Dominant suppression of the ptcB.2.13, Ark82 overgrowth phenotype by a single copy of banΔ1(J). A single copy loss of function yki allele (ykiB5) dominantly suppresses the overgrowth of larval wing discs generated from driving UAS-ptcIR in clones (K), despite the relative clone size remaining the same in both (K′) UAS-ptcIR and (K″) UAS-ptcIR, ykiB5/+.

To test whether Yki activity might contribute to the overgrowth effect of ptc loss, the banΔ1 loss-of-function allele was tested for a dominant effect on the size of ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mosaic 3rd instar larval wing discs. Heterzygosity for banΔ1 potently suppressed of the ptcB.2.13,Ark82 enlarged wing phenotype (Figures 5J), but had no effect on the size of Ark82 mosaic wing discs. The location of yki, Ark, and ptc on the same chromosome arm (2R) prevented similar analysis of the requirement for yki in the background of the ptcB.2.13,Ark82 genotype. To circumvent this, the ykiB5 loss-of-function allele was tested for it's ability to alter the growth of wing discs carrying heat-shock induced clones of cells depleted of Ptc by an RNAi transgene (UAS-ptc-IR; Bloomington). While ykiB5/+ has no effect on otherwise normal discs (data not shown), it substantially suppresses the enlarged size of wing discs carrying clones of Ptc-depleted cells (Figure 5J) without any overt effect on the relative size of the ptc-IR clones (Figure 5K′-K″; GFP marks the UAS-ptcIR clones). Together these data suggest that ptcB.2.13,Ark82 mosaic imaginal discs overgrow due to an increase in Yki activity.

To determine if simply overexpressing Dpp could elicit a similar effect on Yki in proximal wild type cells as loss of ptc, clones of wing disc cells were generated that expressed Dpp from a UAS-dpp transgene. These wing discs are overgrown and show evidence of elevated DIAP1 levels surrounding Dpp-expressing clones, particularly in the pouch (see arrows, Supplemental Figure 3A-B). This effect is consistent both with the parallel effect of Ptc loss on Yki documented here, and the prior finding that cells that cells located on steep gradients of Dpp signaling activate a Yki-dependent growth program (Rogulja et al., 2008).

Discussion

Ptc is a conditional suppressor of growth

Some cancer-causing mutations are proposed to reactivate proliferative programs normally associated with early stages of metazoan development (e.g. (Lipinski and Jacks, 1999). Understanding how factors encoded by these genes can influence cell proliferation pathways during development, or interface with other factors that directly control cell division, growth or survival, is thus a key step in understanding carcinogenic mechanisms. Here we identify the Drosophila gene ptc, a homolog of the PTCH1 tumor suppressor gene, as a conditional suppressor of growth in developing epithelia via an intercellular link between the Hh and Hippo pathways. Immortalization of ptc mutant cells by removal of the Apaf-related gene Ark allows these cells to survive and drive sustained activation of the Hippo-responsive transcriptional co-activator Yki in surrounding cells. The resultant overgrowth can be suppressed by an allele of either yki or the Yki target and pro-growth microRNA bantam. The strength of this suppression suggests Yki hyperactivity is a key contributor to the excess growth elicited by ptc loss in this fly model. Yki activation in wild type cells adjacent to ptc/Ark mutant clones may be linked with elevated expression of the Dpp morphogen, and a concurrent increase in phosphorylation of the Dpp-responsive transcription factor, and Yki-binding partner, Mad. The resultant p-Mad gradient radiating out from ptc,Ark clones correlates with activation of multiple Yki reporters (DIAP1, ban, and expanded) in surrounding wild type cells. These data suggest a model in which blocking the death of ptc mutant disc cells collaborates with ptc mutant cells to create a sustained source of Dpp, which activates Mad in surrounding cells and allows p-Mad:Yki complexes to promote expression of a pro-growth transcriptional program that includes bantam (Oh and Irvine, 2011).

A Drosophila model of human PTCH1 cancer

Although the ptc gene was identified in Drosophila a number of years ago and the human homolog PTCH1 has been implicated in numerous cancers, there is little literature linking ptc and developmental growth control in Drosophila. One possibility for this gap may be tied to our finding that ptc mutant cells require a collaborating block in cell death in order to significantly enlarge developing organs. At a genetic level, the collaboration of ptc-driven tissue growth with an apoptotic block is conserved in mammals: a high percentage of BCCs with mutations in PTCH1 also have mutations in the pro-apoptotic transcription factor p53 (Ling et al., 2001), and a p53 knockout allele accelerates the rate of tumorigenesis in PTCH1 mouse models (Epstein, 2008).

Data here show that wing discs composed mainly of immortalized ptc mutant cells are moderately enlarged relative to controls (Figure 1D), but are smaller than discs which contain immortalized ptc mutant cells mixed with genetically normal cells, indicating that the presence of wild type cells in the same organ enhances the ability of ptc,Ark mutant cells to drive tissue overgrowth. The requirement for genetic heterogeneity may be due to the inhibitory effects of Dad, which is elevated within ptc,Ark cells, or by a requirement for a Dpp gradient to activate Yki in cells surrounding ptc,Ark clones (e.g. (Rogulja et al., 2008). These type of cell:cell interactions are important determinants of cancer cell survival, growth and metastasis in mammals (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011), and the ptc,Ark fly model may provide an opportunity to study this relationship in vivo defined genetic mosaics.

Our finding of a link between Ptc and Yki in Drosophila wing development may be generalizable to other contexts and organisms. Vertebrate homologs of Yki and Dpp, Yap1 and the TGFβ morphogen, arealteredin human tumors with deregulated Hh signaling. One study found an increase in expression of TGF-β and several associated Smad proteins in human BCC samples, while another documented an increase in Yap1 levels in medulloblastoma cells and tissue samples (Fernandez et al., 2009; Gambichler et al., 2007). Data presented here suggest that these phenomena could be linked, and that mutations that alter Hh activity in vertebrates could alter Yap1-driven proliferation via paracrine or autocrine mechanisms. Insight into these mechanisms could provide important opportunities for therapeutic intervention in the treatment of human tumors lacking PTCH1.

Supplementary Material

Wandering L3 larval eye discs were dissected and stain with a marker of differentiation (Elav) and it was found that ptcB.2.13,Ark82 clones (A-A″) prematurely differentiation, see arrow; while. Ark82 mosaic eye discs (B-B″) differentiate similarly to the wild type cells. Mutant cells marked by lack of GFP.

Mosaic larval wing discs were dissected from ptcB.2.13 mosaic wing discs and stained with marker of different pathways including Hedghog (A-A″)stained with anti-Patched (Ptc), compare to figure 3B-B″, Dpp (B-B″). stained with anti-Phosphorylated Mothers Against Decapentaplegic (p-Mad1/5), compare to figure 4A-B″, and Yki (C-C″) stained with anti-Drosophila Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein 1 (DIAP1), compare to figure 5A-B″.

Larval wing discs overexpressing Dpp (marked by the presence of GFP)(A-A″) via UAS-dpp demonstate an overgrowth wing disc accompanying an increase in DIAP1, most elevated in those cells not overexpressing the Dpp protein, see arrows.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to those whose work we could not cite due to space constraints. We thank many members of the Drosophila community for gifts of reagents and stocks including J.Abrams for the Ark82 allele. We thank the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, and Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for fly stocks and antibodies. We thank members of the Moberg lab, the Emory fly community, and the UDM biology department for helpful and insightful discussions. KHM is supported by NIH 2RO1-CA123368; JDK is supported by NIH/NIGMS K12 GM000680.

References

- Akdemir F, Farkas R, Chen P, Juhasz G, Medved'ova L, Sass M, Wang L, Wang X, Chittaranjan S, Gorski SM, Rodriguez A, Abrams JM. Autophagy occurs upstream or parallel to the apoptosome during histolytic cell death. Development. 2006;133:1457–1465. doi: 10.1242/dev.02332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon C, Zaromytidou AI, Xi Q, Gao S, Yu J, Fujisawa S, Barlas A, Miller AN, Manova-Todorova K, Macias MJ, Sapkota G, Pan D, Massague J. Nuclear CDKs drive Smad transcriptional activation and turnover in BMP and TGF-beta pathways. Cell. 2009;139:757–769. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano M, Nevins JR, Wharton RP. Ectopic E2F expression induces S phase and apoptosis in Drosophila imaginal discs. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1422–1432. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.11.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale AE. Hedgehog signaling and human disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2002;3:47–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.3.022502.103031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boedigheimer M, Bryant P, Laughon A. Expanded, a negative regulator of cell proliferation in Drosophila, shows homology to the NF2 tumor suppressor. Mech Dev. 1993;44:83–84. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(93)90058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke J, Hipfner DR, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. bantam encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell. 2003;113:25–36. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran RB, Scott MP. A mouse model for medulloblastoma and basal cell nevus syndrome. J Neurooncol. 2001;53:307–318. doi: 10.1023/a:1012260318979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W, Xie JE, Dyson N. Ectopic expression of dE2F and dDP induces cell proliferation and death in the Drosophila eye. Embo J. 1996;15:3684–3692. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman-Scheel M, Weng L, Xin S, Du W. Hedgehog regulates cell growth and proliferation by inducing Cyclin D and Cyclin E. Nature. 2002;417:299–304. doi: 10.1038/417299a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein EH. Basal cell carcinomas: attack of the hedgehog. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:743–754. doi: 10.1038/nrc2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez LA, Northcott PA, Dalton J, Fraga C, Ellison D, Angers S, Taylor MD, Kenney AM. YAP1 is amplified and up-regulated in hedgehog-associated medulloblastomas and mediates Sonic hedgehog-driven neural precursor proliferation. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2729–2741. doi: 10.1101/gad.1824509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambichler T, Skrygan M, Kaczmarczyk JM, Hyun J, Tomi NS, Sommer A, Bechara FG, Boms S, Brockmeyer NH, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Increased expression of TGF-beta/Smad proteins in basal cell carcinoma. Eur J Med Res. 2007;12:509–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson MC, Lehman DA, Schubiger G. Lumenal transmission of decapentaplegic in Drosophila imaginal discs. Dev Cell. 2002;3:451–460. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00264-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert MM, Tipping M, Veraksa A, Moberg KH. A screen for conditional growth suppressor genes identifies the Drosophila homolog of HD-PTP as a regulator of the oncoprotein Yorkie. Dev Cell. 2011;20:700–712. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn H, Wojnowski L, Miller G, Zimmer A. The patched signaling pathway in tumorigenesis and development: lessons from animal models. J Mol Med (Berl) 1999;77:459–468. doi: 10.1007/s001099900018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan IK, Bilder D. Regulation of imaginal disc growth by tumor-suppressor genes in Drosophila. Annu Rev Genet. 2006;40:335–361. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.100738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay BA, Wassarman DA, Rubin GM. Drosophila homologs of baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis proteins function to block cell death. Cell. 1995;83:1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz HM, Chen Z, Scherr H, Lackey M, Bolduc C, Bergmann A. vps25 mosaics display non-autonomous cell survival and overgrowth, and autonomous apoptosis. Development. 2006;133:1871–1880. doi: 10.1242/dev.02356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipfner DR, Weigmann K, Cohen SM. The bantam gene regulates Drosophila growth. Genetics. 2002;161:1527–1537. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.4.1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Wu S, Barrera J, Matthews K, Pan D. The Hippo signaling pathway coordinately regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis by inactivating Yorkie, the Drosophila Homolog of YAP. Cell. 2005;122:421–434. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huangfu D, Anderson KV. Signaling from Smo to Ci/Gli: conservation and divergence of Hedgehog pathways from Drosophila to vertebrates. Development. 2006;133:3–14. doi: 10.1242/dev.02169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H, Imamura T, Ishidou Y, Takase M, Udagawa Y, Oka Y, Tsuneizumi K, Tabata T, Miyazono K, Kawabata M. Interplay of signal mediators of decapentaplegic (Dpp): molecular characterization of mothers against dpp, Medea, and daughters against dpp. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2145–2156. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.8.2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Hui CC. Hedgehog signaling in development and cancer. Dev Cell. 2008;15:801–812. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanuka H, Sawamoto K, Inohara N, Matsuno K, Okano H, Miura M. Control of the cell death pathway by Dapaf-1, a Drosophila Apaf-1/CED-4-related caspase activator. Mol Cell. 1999;4:757–769. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80386-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KW, Bigner SH, Bigner DD, Trent JM, Law ML, O'Brien SJ, Wong AJ, Vogelstein B. Identification of an amplified, highly expressed gene in a human glioma. Science. 1987;236:70–73. doi: 10.1126/science.3563490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letsou A, Arora K, Wrana JL, Simin K, Twombly V, Jamal J, Staehling-Hampton K, Hoffmann FM, Gelbart WM, Massague J, O'Conner MB. Drosophila Dpp signaling is mediated by the punt gene product: a dual ligand-binding type II receptor of the TGF beta receptor family. Cell. 1995;80:899–908. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling G, Ahmadian A, Persson A, Unden AB, Afink G, Williams C, Uhlen M, Toftgard R, Lundeberg J, Ponten F. PATCHED and p53 gene alterations in sporadic and hereditary basal cell cancer. Oncogene. 2001;20:7770–7778. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski MM, Jacks T. The retinoblastoma gene family in differentiation and development. Oncogene. 1999;18:7873–7882. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methot N, Basler K. An absolute requirement for Cubitus interruptus in Hedgehog signaling. Development. 2001;128:733–742. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills K, Daish T, Harvey KF, Pfleger CM, Hariharan IK, Kumar S. The Drosophila melanogaster Apaf-1 homologue ARK is required for most, but not all, programmed cell death. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:809–815. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzny CK, Holmgren R. The Drosophila cubitus interruptus protein and its role in the wingless and hedgehog signal transduction pathways. Mech Dev. 1995;52:137–150. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00397-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson SC, Gilbert MM, Nicolay BN, Frolov MV, Moberg KH. The archipelago tumor suppressor gene limits rb/e2f-regulated apoptosis in developing Drosophila tissues. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1503–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusslein-Volhard C, Wieschaus E. Mutations affecting segment number and polarity in Drosophila. Nature. 1980;287:795–801. doi: 10.1038/287795a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Irvine KD. Cooperative regulation of growth by Yorkie and Mad through bantam. Dev Cell. 2011;20:109–122. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan D. Hippo signaling in organ size control. Genes Dev. 2007;21:886–897. doi: 10.1101/gad.1536007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan D. The hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev Cell. 2010;19:491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellock BJ, Buff E, White K, Hariharan IK. The Drosophila tumor suppressors Expanded and Merlin differentially regulate cell cycle exit, apoptosis, and Wingless signaling. Dev Biol. 2007;304:102–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A, Oliver H, Zou H, Chen P, Wang X, Abrams JM. Dark is a Drosophila homologue of Apaf-1/CED-4 and functions in an evolutionarily conserved death pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:272–279. doi: 10.1038/12984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogulja D, Rauskolb C, Irvine KD. Morphogen control of wing growth through the Fat signaling pathway. Dev Cell. 2008;15:309–321. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwank G, Restrepo S, Basler K. Growth regulation by Dpp: an essential role for Brinker and a non-essential role for graded signaling levels. Development. 2008;135:4003–4013. doi: 10.1242/dev.025635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwank G, Tauriello G, Yagi R, Kranz E, Koumoutsakos P, Basler K. Antagonistic growth regulation by Dpp and Fat drives uniform cell proliferation. Dev Cell. 2011;20:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekelsky JJ, Newfeld SJ, Raftery LA, Chartoff EH, Gelbart WM. Genetic characterization and cloning of mothers against dpp, a gene required for decapentaplegic function in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1995;139:1347–1358. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.3.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyamala BV, Bhat KM. A positive role for patched-smoothened signaling in promoting cell proliferation during normal head development in Drosophila. Development. 2002;129:1839–1847. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staehling-Hampton K, Ciampa PJ, Brook A, Dyson N. A genetic screen for modifiers of E2F in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1999;153:275–287. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.1.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C, Ingham PW. Hedgehog signaling in the Drosophila eye and head: an analysis of the effects of different patched trans-heterozygotes. Genetics. 2003;165:1915–1928. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.4.1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuneizumi K, Nakayama T, Kamoshida Y, Kornberg TB, Christian JL, Tabata T. Daughters against dpp modulates dpp organizing activity in Drosophila wing development. Nature. 1997;389:627–631. doi: 10.1038/39362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal M, Cagan RL. Drosophila models for cancer research. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SJ, Huh JR, Muro I, Yu H, Wang L, Wang SL, Feldman RM, Clem RJ, Muller HA, Hay BA. Hid, Rpr and Grim negatively regulate DIAP1 levels through distinct mechanisms. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:416–424. doi: 10.1038/ncb793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Song Z, Tittel J, Steller H. HAC-1, a Drosophila homolog of APAF-1 and CED-4 functions in developmental and radiation-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell. 1999;4:745–755. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80385-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Wandering L3 larval eye discs were dissected and stain with a marker of differentiation (Elav) and it was found that ptcB.2.13,Ark82 clones (A-A″) prematurely differentiation, see arrow; while. Ark82 mosaic eye discs (B-B″) differentiate similarly to the wild type cells. Mutant cells marked by lack of GFP.

Mosaic larval wing discs were dissected from ptcB.2.13 mosaic wing discs and stained with marker of different pathways including Hedghog (A-A″)stained with anti-Patched (Ptc), compare to figure 3B-B″, Dpp (B-B″). stained with anti-Phosphorylated Mothers Against Decapentaplegic (p-Mad1/5), compare to figure 4A-B″, and Yki (C-C″) stained with anti-Drosophila Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein 1 (DIAP1), compare to figure 5A-B″.

Larval wing discs overexpressing Dpp (marked by the presence of GFP)(A-A″) via UAS-dpp demonstate an overgrowth wing disc accompanying an increase in DIAP1, most elevated in those cells not overexpressing the Dpp protein, see arrows.