Abstract

Background

Many health care organizations are interested in instituting a palliative care clinic. However, there are insufficient published data regarding existing practices to inform the development of new programs.

Objective

Our objective was to obtain in-depth information about palliative care clinics.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of 20 outpatient palliative care practices in diverse care settings. The survey included both closed- and open-ended questions regarding practice size, utilization of services, staffing, referrals, services offered, funding, impetus for starting, and challenges.

Results

Twenty of 21 (95%) practices responded. Practices self-identified as: hospital-based (n=7), within an oncology division/cancer center (n=5), part of an integrated health system (n=6), and hospice-based (n=2). The majority of referred patients had a cancer diagnosis. Additional common diagnoses included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, neurologic disorders, and congestive heart failure. All practices ranked “pain management” and “determining goals of care” as the most common reasons for referrals. Twelve practices staffed fewer than 5 half-days of clinic per week, with 7 operating only one half-day per week. Practices were staffed by a mixture of physicians, advanced practice nurses or nurse practitioners, nurses, or social workers. Eighteen practices expected their practice to grow within the next year. Eleven practices noted a staffing shortage and 8 had a wait time of a week or more for a new patient appointment. Only 12 practices provide 24/7 coverage. Billing and institutional support were the most common funding sources. Most practices described starting because inpatient palliative providers perceived poor quality outpatient care in the outpatient setting. The most common challenges included: funding for staffing (11) and being overwhelmed with referrals (8).

Conclusions

Once established, outpatient palliative care practices anticipate rapid growth. In this context, outpatient practices must plan for increased staffing and develop a sustainable financial model.

Introduction

Clinic-based palliative care for patients with advanced illness holds tremendous promise.1,2 Studies have demonstrated that outpatient palliative care clinics can lead to improvements in quality of life, reduction in health services utilization, and potentially improved survival.3,4 Evidence suggests that palliative care clinic programs are increasing in number.5

Unfortunately, there is little published information on the development and management of palliative care clinics.3,5–7 Clinicians and administrators seeking to start and grow palliative care clinics lack basic information regarding the optimal staffing structure, funding sources, types of patients seen, and the potential challenges and barriers.8 Often, those seeking to start a new practice or grow an existing one must rely on one-on-one communication with other practices to understand operational aspects of program development. Although palliative care remains a small field and individual communication remains feasible, published data from established programs would be a significant contribution to the field. Thus, we sought to obtain information on the practice of outpatient palliative care from a broad range of practices.

We previously conducted a focused survey of 11 outpatient palliative care practices associated with a cancer center.7 We sought to build on our previous study by administering a more detailed survey to a diverse sample of outpatient palliative care practices. The specific goals of this project were:

To understand the impetus for starting palliative care clinics.

To obtain information on the staffing, finances, and scope of services provided by palliative care clinics.

To gather information about the barriers to clinic development, sustainability, and growth.

Methods

We designed a cross-sectional survey with the goal of obtaining detailed information from a small but diverse sample of practices. Based on personal knowledge and participation in professional conferences and refined through discussion among three of the researchers (AKS, JNT, MWR), we developed a convenience sample of 21 leading practices from diverse settings. We sought subjects that varied across a range of characteristics: geography, size, patient characteristics, health system affiliation, and years in practice. There were no specific exclusion criteria. The person most familiar with the clinical/operational aspects of the practice was identified via professional contacts or based on information available on the practice website. Potential participants were contacted via e-mail or phone. Those who agreed to participate in the study faxed informed consent to the study investigators. Nonresponders were sent two reminder e-mails. The data were collected using an online survey instrument administered via SurveyMonkey® (SurveyMonkey, Palo Alto, CA). Data were collected over a 2-month period in 2011. The study design was approved by the Committee on Human Subjects at the University of California, San Francisco.

Survey questions were generated from a review of the outpatient palliative care literature and consultation with researchers, clinicians, and leaders in the development of outpatient palliative care. Quantitative questions included information on: practice size and utilization, patient referrals, funding and affiliation, staffing and services, and clinical and administrative operations. Questions used a mixture of: direct entry (e.g., “How many new patients were seen in your practice in the last year?”); ranking (e.g., “Rank the top three services provided by your clinic.”); and yes/no (e.g., “Do you prescribe opioid medications directly to patients?”). Qualitative questions addressed information that might be captured better with stories and words than numbers, including questions about the impetus for starting the practice, how the practice defines success, and the most challenging experiences. A copy of the survey is available at https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/TM9GVSX.

Quantitative results are presented descriptively. Open-ended responses were coded by two reviewers (AKS and JNT) and, following review of the coding by a third author (MWR), grouped into the presented themes. Finally, we present in-depth profiles of 4 practices operating in different health system environments, one each from hospital-based, integrated health system-based, oncology division or cancer center-based, and hospice-based.

Results

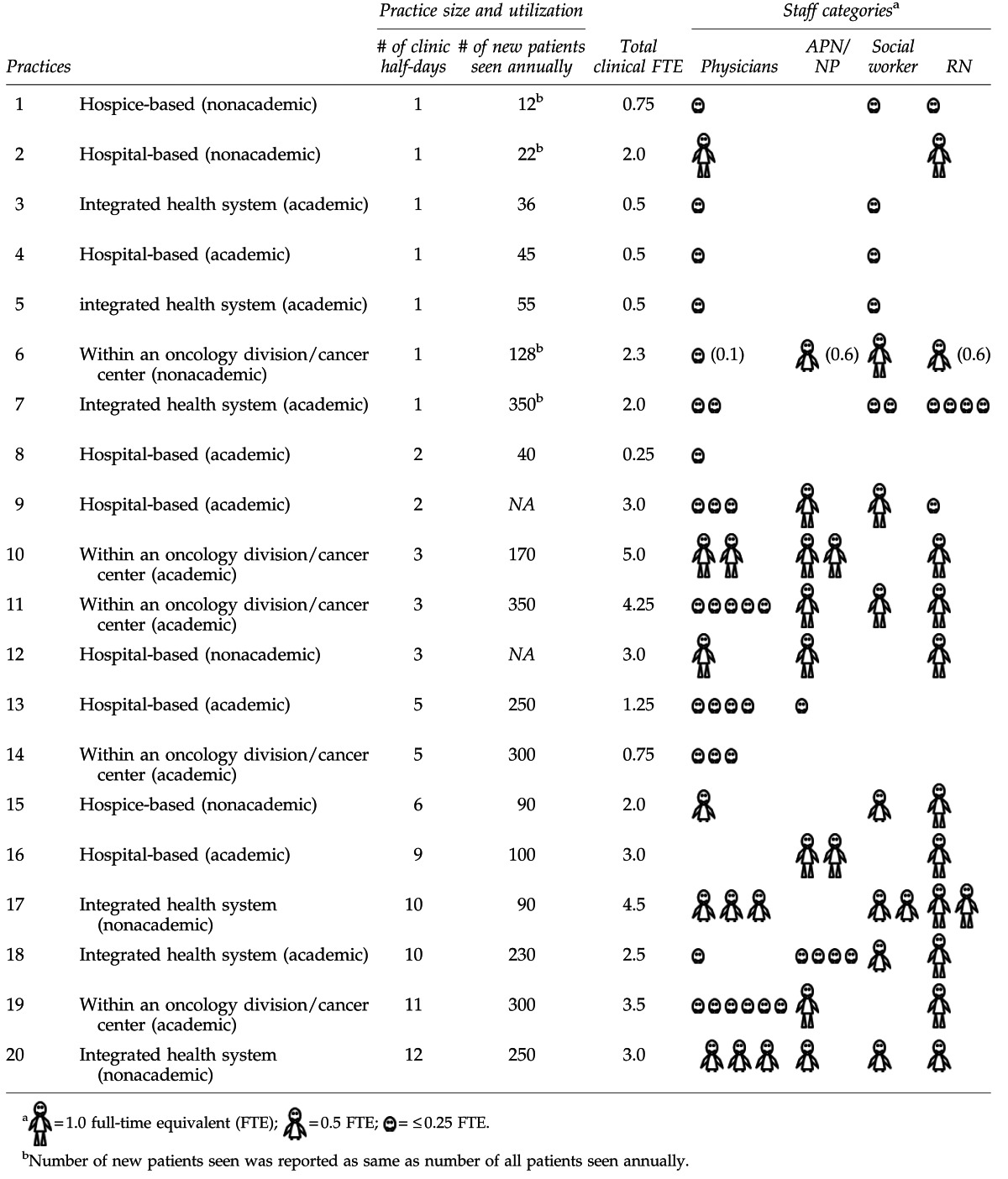

Twenty of 21 (95%) practices responded; 2 chose to remain anonymous, the remaining 18 are listed in Table 1. Characteristics of the group are summarized below and in Table 2. Four practices are profiled in depth in Tables 3A through 3D.

Table 1.

Included Outpatient Palliative Care Clinics (n=20a)

| Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH |

| Denver VA Medical Center, Denver, CO |

| Greater Baltimore Medical Center, Baltimore, MD |

| Hackensack University Medical Center, Hackensack, NJ |

| Hospice of Foothills, Grass Valley, CA |

| Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, WA |

| Hospice of the Bluegrass, Lexington, KY |

| Kaiser Permanente, Denver, CO |

| Kaiser Permanente, Fontana, CA |

| Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA |

| Mt. Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY |

| San Francisco VA Medical Center, San Francisco, CA |

| University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL |

| University of Colorado Heart Center, Denver, CO |

| University of Rochester, Strong Memorial Hospital, Rochester, NY |

| University of California, San Francisco, CA |

| University of Texas, Southwestern, Dallas, TX |

| West Los Angeles VA Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA |

Two practices preferred to remain anonymous.

Table 2.

Amount of Full-Time Equivalent (FTE) per Staff Category at 20 Outpatient Clinics

|

Table 3A.

Profile of a Hospital-Based Clinic

| Name (contact) | Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, WA (Dr. Darryl Owens) |

| Patient volume | 400 patients per year, including 100 new |

| Patient characteristics | 50% with cancer, most common noncancer diagnoses are end-stage renal disease, end-stage liver disease, and dementia. Major reasons for referral are symptom management and goals-of-care discussions. 50% of referrals are from inpatient palliative care consultation services, 30% from oncologists, and 20% from nephrologists. |

| Practice characteristics | 9 half-days of clinic/week with average of two exam rooms available per clinic session. New patient visits are 60 minutes, follow-up visits 30 minutes. Wait time averages 10 days. |

| Staffing | 4 part-time physicians (fellows), 2 near full-time advanced practice nurses or nurse practitioners, 1 half-time social worker, 1 full-time nurse (RN) |

| Funding | 50% billing, 40% institutional support, 10% foundation grant |

| Routinely collected data | Appointment data (e.g., no-shows, cancellations), demographics, hospital admissions, emergency department visits, hospice use, patient satisfaction, and date of death |

| Impetus for starting | “To provide continuity of care and 24-hour access to palliative care providers. The Primary Palliative Care Clinic was started to provide both primary and palliative care (with providers specialized in both) to patients with a life-limiting illness and no primary care provider. We are an inner city hospital where the wait list for establish primary care providers is over 400 patients long. We were asked by the nephrologists to provide primary care and pain management to their patients after I presented data from Woody Moss's presentation regarding end-stage kidney disease.” |

| Innovation | Strong public service mission: “We assume responsibility for management of patients released from prison on compassionate release for terminal illness. Approximately 20% of our patients are homeless. A majority have limited or no health insurance.” |

| Definition of success | “Avoidance of emergency department usage and readmission to the hospital.” |

| Challenges faced | Funding for staffing: “Our institution loves the concept and work of our clinic as long as they don't have to pay for much.” |

Table 3D.

Profile of a Hospice-Based Clinic

| Name (contact) | Hospice of the Bluegrass, Lexington, KY (Dr. Todd Cote) |

| Patient volume | 180 patients per year, including 90 new |

| Patient characteristics | 30% with cancer, most common noncancer diagnoses are heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and dementia. Major reasons for referral are symptoms and goals-of-care discussions. 50% of referrals are from inpatient palliative care consultation services, 20% from oncologists, and 20% from primary care providers. |

| Practice characteristics | 6 half-days of clinic/week with average of 3 exam rooms available per clinic session. New patient visits are 90 minutes, follow-up visits 30 minutes. Wait time averages 7 days. |

| Staffing | 1 half-time physician, 1 full-time social worker, 1 full-time nurse (RN) |

| Funding | 60% institutional support and 40% billing |

| Routinely collected data | None |

| Impetus for starting | This practice started 8 years ago to “Fill in community care ‘gaps’ and offer post hospital support for patients who received a palliative care consult.” |

| Innovation | Offers telemedicine services for patients in rural Appalachia. |

| Definition of success | High utilization of home health and hospice services. |

| Challenges faced | Generating enough patient referrals, “Not becoming a chronic pain clinic.” |

Table 3B.

Profile of a Clinic Based in an Integrated Health System

| Name (contact) | Kaiser Permanente, Fontana, CA (Dr. Thomas Cuyegkeng) |

| Patient volume | 300 patients per year, including 250 new |

| Patient characteristics | 60% with cancer, most common noncancer diagnoses are heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic renal failure. Major reasons for referral are symptom management, emotional support, and psychosocial support. 60% of referrals are from oncologists, 30% from primary care providers, and 10% from inpatient palliative care consultation services. |

| Practice characteristics | 12 half-days of clinic/week with average of 1 exam room available per clinic session. New patient visits are 60 minutes, follow-up visits 60 minutes. Wait time averages 5 days. |

| Staffing | 3 part-time (approx 40% each) physicians, 1 half-time advanced practice nurse or nurse practitioner, 1 half-time social worker, 1 half-time nurse (RN) |

| Funding | 100% institutional support |

| Routinely collected data | None |

| Impetus for starting | This practice started 6 years ago. “The impetus for starting this practice is to provide palliative services UPSTREAM for patients with life-threatening conditions who do not otherwise qualify (or elect) hospice or home-based palliative care.” |

| Innovation | Strong integration with inpatient services: “The integration of hospital and clinic-based palliative medicine permits us to be flexible in meeting the needs of patients and gives us the ability to provide care in-between hospitalizations for patients pursuing active treatments.” |

| Definition of success | “Being able to provide patients and their families the care they need and maintaining balance in the busy workday for the team members.” |

| Challenges faced | Getting patients early enough in their illness, funding for staffing. “Our patients frequently come to us late—making the ‘catch-up’ work needlessly harried. Patients could benefit more from this service if referred early (e.g., at time of diagnosis) instead of when a crisis of care occurs. Funding for adequate staff competes with the other specialties that are high volume and high profile (compared to palliative medicine).” |

Table 3C.

Profile of a Clinic Based in an Oncology Division

| Name (contact) | Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (Dr. Juliet Jacobsen) |

| Patient volume | 498 patients per year, including 300 new |

| Patient characteristics | 95% with cancer. Major reasons for referral are symptom management, psychosocial support, and goals-of-care discussions. 60% of referrals are from oncologists, 20% from inpatient palliative care consult services, and 20% from primary care providers. |

| Practice characteristics | 11 half-days of clinic/week with average of 1 exam room available per clinic session. New patient visits are 60 minutes, follow-up visits 30 minutes. Wait time averages 7 days. |

| Staffing | 6 part-time (approx 15% each) physicians, 1 full-time advanced practice nurse or nurse practitioner, 1 full-time nurse (RN) |

| Funding | 50% institutional support and 50% billing |

| Routinely collected data | Appointment data (e.g., no-shows, cancellations) |

| Impetus for starting | This practice started 7 years ago “To better serve patients who have ongoing needs for palliative care.” |

| Innovation | “Working with patients early in the course of illness. Working closely with referring oncologists—high rates of collaboration/joint visits.” |

| Definition of success | “Patients who need to be seen are scheduled and seen promptly. Clinic schedules are full. Appropriate coverage of clinic patients in terms of phone calls returned and scripts filled.” |

| Challenges faced | Competing practice priorities. |

Impetus for starting

When asked to describe the impetus for starting a palliative care clinic, the major theme identified was to address unmet symptoms and psychosocial needs of patients with serious illness, and to engage patients in goals-of-care discussions that were not happening. Clinic practices were often started by inpatient palliative care providers who realized that the patients they cared for in the hospital setting were experiencing poor-quality care in the outpatient setting. The following quote from Dr. Elizabeth Paulk at the University of Texas, Southwestern exemplifies this theme:

I was appalled [as a house officer] by the number of terminally ill patients I was seeing come through the Emergency Department…who had uncontrolled pain and were totally uninformed about their diagnosis, prognosis, goals of care, and options for management. We are based at a county hospital, and my observation was that inpatients are generally (though not always) pretty well cared for. However, there are very significant problems once patients go home. There are communication problems with their oncology providers, pain and other symptoms are not well cared for, advance care planning is not addressed, and there are not enough social workers in the ambulatory setting to help care for the patients when they are part of the general population of ambulatory patients. My goal was to create a home for patients with limited life expectancy to get them feeling better, optimize the social situation, and help make sure they actually understood what was going on with their disease.

Similarly, other providers talked about filling in the gap between existing ambulatory care practices and inpatient care. One anonymous provider stated that she observed patients “falling through the cracks” after hospital discharge. None of the practices in our sample were created primarily at the request of medical center administrators or leaders.

Affiliation

Although the practices often reported multiple affiliations, for the purposes of the descriptive analysis we categorized them into four groups based on their primary affiliation: hospital-based (n=7, 35%), integrated health system (n=6, 30%), oncology division or cancer center (n=5, 25%), or hospice (n=2, 10%). Seven of 11 (64%) practices located within an integrated health system or oncology division had been in existence for 5 or more years. In contrast, only 3 of the other 9 practices had been in existence for 5 or more years.

Clinic and patient characteristics

Five of the 20 (25%) practices used a clinical database to provide information regarding the number and type of patients seen annually, whereas the remaining 15 (75%) provided their “best estimate.” Given our attempt to include practices of varying size, the total number of patients cared for annually varied widely. Eleven of 20 (55%) practices cared for less than 200 patients per year (range 12–170). Seven of 20 (35%) cared for 200 or more patients per year (range 230–350). Similarly, the number of half-days of outpatient clinic per week varied widely, with 12 of 20 (60%) practices offering fewer than 5 half-days of clinic per week and 8 of 20 (40%) offering 5 or more half-days of clinic per week.

Staffing ratios also varied widely with a range of full-time equivalents (FTEs) of 0.25 to 5.0. Although the number of patients seen annually generally tracked with the number of half-days of clinic offered, several outliers could be identified (Table 2). These differences could be attributable to differences in staffing, or number of rooms available for patients to be seen during a half-day of clinic. For example, practice 5 and 7 in Table 2 are both located within an integrated health system. Practice 5 reports seeing 55 new patients per year in one half-day of clinic per week, whereas practice 7 in Table 2 reported seeing 350 new patients in one half-day of clinic per week. Staffing differed between practices as well. Practice 5 has only one part-time physician and one part-time social worker, whereas practice 7 has two part-time physicians, two part-time social workers, and four part-time nurses (Table 2).

Average visit times varied widely. The average time for a new patient visit was 65 minutes (range of 40–120 minutes) and average time for a follow-up visit was 37 minutes (range 20–90 minutes). The average number of visits per patient was 5, but the range was wide (2–22). Eight of 20 practices reported average wait times for a first appointment upon receipt of a new referral of more than one week. Twelve of 20 practices reported that they provide telephone or in-person coverage 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Ten of the practices offered home visits.

Cancer was by far the most common diagnosis of patients referred to the palliative care clinic in our sample. In 14 of 20 practices, more than 50% of patients seen within the previous year had a cancer diagnosis. Practices were asked to rank their top three noncancer diagnoses: 12 ranked chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the top three, 8 ranked neurologic disorders, and 8 ranked congestive heart failure. Ten practices cared for patients with chronic noncancer pain.

There was general alignment between the reasons patients were referred to the clinic and the services outpatient palliative care clinicians said they provided. The following were ranked in the top reasons for referral: pain and nonpain symptom management (top three reason for 14 practices), determining goals of care (11 practices), and psychological issues (6 practices). The most common nonpain symptoms were depression (4 practices) and dyspnea (3 practices). When asked to rank the top services provided, the results were: determining goals of care (top three for 18 practices), pain and nonpain symptom management (17 practices), and social support (10 practices). The discrepancies between the top reason for referrals and top services provided may reflect that patients are most commonly referred for symptom management, but palliative care providers believe that they uncover unmet needs around goals-of-care discussions and social support.

Eighty percent of practices (n=16) care for patients in a co-management model with another health care provider, where each clinician assumes primary responsibility for a separate area of concern and both manage some concerns jointly (e.g., oncologist prescribes chemotherapy, palliative care clinician prescribes analgesics, and both address goals of care). Two practices report assuming primary responsibility for all patient care. Two practices only make recommendations to the primary clinicians and do not write prescriptions.

Funding

Most clinics (n=17, 85%) relied on a combination of funding sources, including institutional support, billing revenue, philanthropy, research funding, and private foundation support. Institutional support and billing revenue were the most common sources of funding. Nine clinics (45%) reported that institutional support provided 50% or more of their practice funding. Eight clinics (40%) reported that billing revenue provided 50% or more of their practice funding; 2 practices (10%) reported that billing revenue provided 100% of funding.

Innovation

Not unexpectedly, when asked to describe the innovative features of their programs, the responses were unique to each practice and could not be grouped into distinct themes. For example, the University of Colorado Heart Center outpatient clinic run by Dr. David Bekelman cares for patients with heart failure and chronic lung disease. Clinicians there note utilization of standardized disease-specific measures of symptoms, physical function, and quality of life at each visit. A program that preferred to remain anonymous noted that in contrast to most models, its practice is almost entirely run by advanced practice nurses. Dr. Barbara Drye of the San Francisco VA Medical Center noted that her practice is located in a primary care clinic, as opposed to an oncology clinic, and uses the Veterans Administration's electronic medical record, facilitating ease of communication with referring and treating providers.

Definition of success

Most practices reported that patient-centered outcomes mattered most for defining the success for their practice. These outcomes included patient satisfaction, improved quality of life, and reduction in symptoms. Of note, 10 clinics (50%) reported tracking symptoms in a database, and 5 clinics (25%) tracked patient satisfaction (we did not ask if clinics tracked quality of life). In contrast, when asked how success is defined for the affiliated organization or institution, process and health systems outcomes were described, including maintaining a busy clinic schedule, decreasing emergency department visits and hospitalizations, and timely hospice enrollment. Thirteen clinics (65%) tracked appointment data such as clinic volume and no-shows, 6 clinics (30%) tracked hospitalizations, 5 clinics tracked emergency department visits (25%), 8 (40%) tracked hospice use, and 8 (40%) tracked location of death.

Major challenges

Interestingly, whereas 8 practices reported being overwhelmed with referrals, 5 practices reported difficulty generating referrals. Eighteen clinics anticipated a growth in patient volume over the next year, and 11 clinics stated they were below staff capacity to meet anticipated needs. Similarly, 11 clinics reported that they lacked funding for staffing. As an example, a practice director who preferred to remain anonymous stated:

Funding from the cancer center is from philanthropy. The cancer center has not agreed to increase funding for staff. Our wait time has been about 2 months for a new patient from our inception. We know some referrals are not being made because of the referring doctor's understanding of our wait time. Our current expansion with a nurse practitioner is coming from our own practice revenue.

Dr. Timothy Quill from the University of Rochester's Strong Memorial Medical Center's clinic described an initial lack of consultations due to the perception that the clinic's focus was end-of-life care. He wrote that there was a, “delicate balance between generating new referrals and being too busy. We had to establish clearly that we were not about end-of-life care. Once this was established referring providers were very eager to have our services. We now do a lot of symptom management for the teams.”

Discussion

Palliative Care clinics are increasing in number, but little data from existing practices exist to help guide their development and growth. Our results provide a glimpse into the development and management of a diverse sample of outpatient palliative practices. We sampled practices that varied with respect to their geographic location, practice size, patient population, and health system affiliation.

Our findings suggest that it is essential that developing practices include both a plan for marketing and a strategy to accommodate growth. Our data suggest that the volume seen in clinic practices can increase very quickly. Almost all practices anticipated expanding within the next year and the majority reported staffing shortages. Nearly half had wait times of a week or more for an appointment, which is clearly too long for a patient in need of urgent palliative care assistance. A major challenge faced by many practices was the lack of funding to hire additional staff.

Compared with inpatient palliative care, the business case for a palliative care clinic is still a work in progress. Billing revenue and institutional support were the most common sources of funding; all but 3 practices required more than one source of support. These findings suggest that to survive and grow in the current financial environment, outpatient clinic practices must align with at least one additional funding source such as the larger medical institution, obtain grant or philanthropic support, or demonstrate reductions in global costs to the system. Developing a plan that anticipates growth and matches service goals to goals of the funding entity is essential to a scaleable and sustainable program.

As our health system moves away from fee for service toward models based on shared savings, accountable care organizations, and bundled payments, the business case for palliative care clinics that save money for the system as a whole may become more obvious. The question facing many practices currently based in a strictly fee-for-service system is how to plan for those days while surviving on a fee-for-service income. Practice leaders in fee-for-service systems might schedule a meeting with regional payers to seek support or payment innovations for outpatient palliative care, as well as health administrators planning the transition to an accountable care organization model.

Our study raises additional questions. It was not designed to examine outcomes that institutional stakeholders care about, such as reductions in costs, emergency department visits, hospitalizations/readmissions, and the efficiency of the referring clinicians.9 For example, does referral of a patient with cancer to a palliative care practice for symptom management and goals-of-care discussions allow the referring oncologist to be more efficient? Our results suggest wide variation in the volume of patients seen per clinical FTE, but we could not account for the wide variety of factors that might explain these differences, such as interpretation of the term “full-time equivalent,” severity and complexity of illness, staffing models, skill sets of clinical providers, or number of rooms available.

Our study had limitations; the sample size was small, precluding statistical comparisons, and it was not nationally representative. Unfortunately, at this time there is no established registry of outpatient palliative care practices that would allow for creation of such a national sample. We relied on self-report, and a minority of our respondents used a database when estimating patient volume. Furthermore, we have little information about the optimal efficiency or productivity of palliative care practices.5 Nonetheless, as in other fields where productivity is measured and benchmarked, outpatient palliative care practices should consider leading the way in establishing these markers, before administrative and institutional forces take on these tasks.

Palliative care clinics are increasing in number and size in multiple health care settings. Outpatient practices must meet the challenges of creating funding models that are not only sustainable, but also allow for growth of patient volume and staff. These practices are caring for patients with a variety of illnesses and utilizing an assortment of staffing models with wide variation across practices. The Center to Advance Palliative Care is currently developing resource material for those seeking to start or grow an outpatient palliative care practice (Improving PALliative Care, or IPAL).10 In conjunction with these technical assistance materials, we hope these data provide guidance to those starting a new palliative care clinic or seeking to expand an existing one.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Smith was supported by the National Center for Research Resources UCSF-CTSI (UL1 RR024131). Marie A. Bakitas, APRN, DnSc, was support by NINR grant number 1R01NR011871-01.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Meier DE. Beresford L. Outpatient clinics are a new frontier for palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:823–828. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.9886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferris FD. Bruera E. Cherny N, et al. Palliative cancer care a decade later: Accomplishments, the need, next steps—from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3052–3058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabow MW. Dibble SL. Pantilat SZ. McPhee SJ. The comprehensive care team: A controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:83–91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Temel JS. Greer JA. Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger GN. O'Riordan DL. Kerr K. Pantilat SZ. Prevalence and characteristics of outpatient palliative care services in California. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:2057–2059. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hui D. Elsayem A. De la Cruz M, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303:1054–1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabow MW. Smith AK. Braun JL. Weissman DE. Outpatient palliative care practices. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:654–655. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Twaddle ML. Maxwell TL. Cassel JB, et al. Palliative care benchmarks from academic medical centers. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:86–98. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muir JC. Daly F. Davis MS, et al. Integrating palliative care into the outpatient, private practice oncology setting. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Center to Advance Palliative Care. www.capc.org. [Aug 7;2012 ]. www.capc.org