Abstract

The ubiquitin–proteasome system and the autophagy–lysosome pathway are the two main mechanisms for eukaryotic intracellular protein degradation. Proteasome inhibitors are used for the treatment of some types of cancer, whereas autophagy seems to have a dual role in tumor cell survival and death. However, the relationship between both pathways has not been extensively studied in tumor cells. We have investigated both proteolytic systems in the human epithelial breast non-tumor cell line MCF10A and in the human epithelial breast tumor cell line MCF7. In basal condition, tumor cells showed a lower proteasome function but a higher autophagy activity when compared with MCF10A cells. Importantly, proteasome inhibition (PI) leads to different responses in both cell types. Tumor cells showed a dose-dependent glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3)β inhibition, a huge increase in the expression of the transcription factor CHOP and an active processing of caspase-8. By contrast, MCF10A cells fully activated GSK-3β and showed a lower expression of both CHOP and processed caspase-8. These molecular differences were reflected in a dose-dependent autophagy activation and cell death in tumor cells, while non-tumor cells exhibited the formation of inclusion bodies and a decrease in the cell death rate. Importantly, the behavior of the MCF7 cells can be reproduced in MCF10A cells when GSK-3β and the proteasome were simultaneously inhibited. Under this situation, MCF10A cells strongly activated autophagy, showing minimal inclusion bodies, increased CHOP expression and cell death rate. These findings support GSK-3β signaling as a key mechanism in regulating autophagy activation or inclusion formation in human tumor or non-tumor breast cells, respectively, which may shed new light on breast cancer control.

Keywords: autophagy, proteasome, GSK-3β, breast cancer, protein aggregates, BAG proteins

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and the autophagy—lysosomal pathway are the two main systems for eukaryotic intracellular protein degradation. The 26S-proteasome is responsible for catalysis of the ATP-dependent degradation of poly-ubiquitinated proteins.1, 2 In this sense, K48-ubiquitination is the canonical mark for proteins degraded by the proteasome.3 Moreover, in the presence of the pro-inflammatory cytokines interferon (IFN)-γ or TNF-α cells can induce the synthesis of the immunoproteasome.4, 5, 6 Unlike the UPS, the autophagy—lysosomal pathway is a catabolic process that can sequester and degrade cytoplasmic components through the lysosomes. Among the three types of autophagic degradation,7 macroautophagy (hereinafter referred to as autophagy) is the most important form of autophagy. It involves the formation of a double-membrane vesicle, called autophagosome, initiated by elongation of a de novo-formed membrane that seals on itself, sequestering cargo inside. Finally, the double-membrane vesicle fuses with lysosomes leading to autophagolysosome formation, where the cargo is degraded. Selective degradation of proteins is thought to be an exclusive function of the UPS, but a growing body of evidence claims that participation of autophagy may also be relevant. The identification of proteins that target proteins for autophagy degradation, or mediate cargo of phagosomes, argues in favor of this idea. Destination of proteins for proteasome or autophagy degradation is regulated, at least in part, by the Bcl-2-associated athanogen (BAG) proteins. The expression of BAG1 and BAG3 acts as a molecular switch mechanism determining whether proteins are degraded by the proteasome or autophagy, respectively.8, 9 In this sense, BAG3 was found to act in concert with the ubiquitin-binding protein p62/SQSTM1 to increase autophagic activity. Moreover, p62/SQSTM1 binds also to LC3II- and K63-ubiquitinated proteins, putting together all the elements necessary for the autophagy activation and targeted cargo proteins. Here we focused on both the proteolytic systems in a non-tumor and in a tumor cell line. We show that tumor cells are more dependent on autophagy. Indeed, proteasome inhibition (PI) in MCF10A cells induced the formation of inclusion bodies with minor cell death, while increased basal autophagy in MCF7 cells, avoiding the formation of inclusion bodies, but raising the cell death rate. We provide solid evidence supporting that glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3)β inhibition regulates autophagy activation induced by PI in the human breast cancer MCF7 cells.

Results

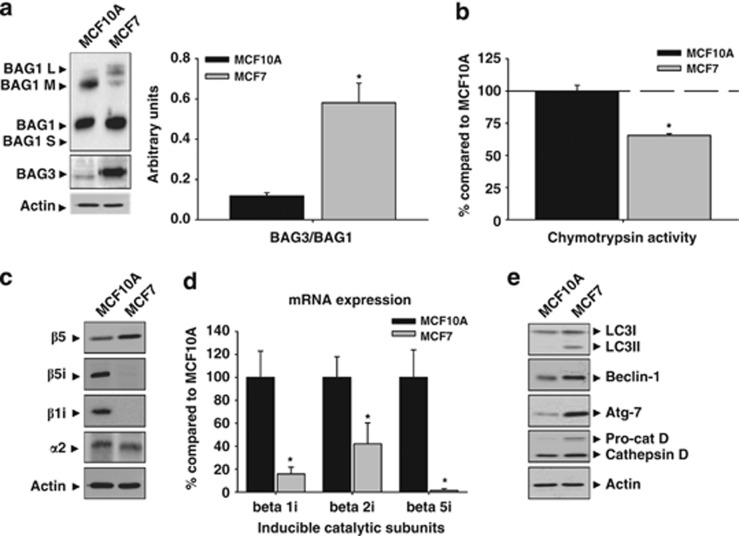

BAG1 and BAG3 are differentially expressed in MCF10A and MCF7 cells

As BAG-family proteins are involved in protein quality control,10, 11, 8 we characterized the expression of BAG1 and BAG3 in MCF7 and MCF10A cells, respectively. Among the four BAG1 isoforms,12 BAG1 (∼36 kDa) and BAG1M (∼46 kDa) were mostly detected in MCF10A cells, whereas in MCF7 cells predominated BAG1, in a very low extent, BAG1M and BAG1L (∼50 kDa) (Figure 1a). On the other hand, basal expression of BAG3 was higher in MCF7 than in MCF10A cells, where it was practically absent (P<0.05; Figure 1a). In consequence, the BAG3/BAG1 (∼36 kDa) ratio was fourfold higher in tumor than in non-tumor cells.

Figure 1.

Proteasome and autophagic markers expressed in MCF10A and MCF7 cells in basal condition. (a) Different isoforms of the BAG1 protein were expressed in the MCF10A and MCF7 cells. In MCF10A cells BAG1 (∼36 kDa) and BAG1M (∼46 kDa) isoforms were detected, whereas BAG1 predominated in MCF7 cells. The BAG3 protein was observed in MCF7 but not in MCF10A cells. The graph shows the BAG3/BAG1(∼36 kDa) ratio in both cell types. Data are presented as mean±S.D. of three independent experiments. (b) The chymotrypsin activity of proteasome was lower in MCF7 compared with MCF10A cells. Data are presented as mean±S.D. of four independent quantifications. (c) Constitutive and inducible proteasome catalytic subunits expressed in MCF10A and MCF7 cells. Note the low expression of inducible subunits in MCF7 cells. Experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results. (d) The mRNA expression of inducible catalytic subunits is downregulated in MCF7 cells compared with MCF10A cells. Data are presented as mean±S.D. of three independent experiments. MCF10A and MCF7 cells were analyzed in parallel. (e) Molecular markers of autophagy and cathepsin D expressed in MCF10A and MCF7 cells. Note the lower expression in MCF10A compared with MCF7 cells. Experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results. *P<0.05, significant differences compared with MCF10A cells

Proteasome activity predominates in MCF10A and autophagy markers are increased in MCF7 cells

We further analyzed whether the different expression of BAG1 and BAG3 affected intracellular proteolytic systems. As shown in Figure 1b, MCF7 cells showed a significant reduction in the chymotrypsin-like activity of proteasome when compared with MCF10A cells (P<0.05). This activity is catalyzed by both the constitutive β5 and the inducible β5i/LMP7 subunits.1, 13 Both the subunits were expressed in MCF10A cells, but only the constitutive β5 in MCF7 cells was detected (Figure 1c). The low expression of β5i/LMP7 was not restricted to this subunit, but also to the β1i/LMP2 (Figure 1c). This could be consequence of the very low, if any, transcriptional expression of both subunits (Figure 1d). However, the structural subunit α2, present in both constitutive and immunoproteasome, was similarly expressed in both cell types, pointing to qualitative rather than quantitative differences in proteasomes between MCF7 and MCF10A cells. On the other hand, MCF7 cells showed a higher expression of several proteins related to the autophagy—lysosomal system. The autophagosome marker LC3II, in addition to proteins involved in the initiation of autophagy, such as Beclin-1 and Atg7, or the lysosomal enzyme cathepsin D, were more expressed in MCF7 than in MCF10A cells (Figure 1e). These data strongly indicate that intracellular proteolytic systems are altered in tumor MCF7 cells.

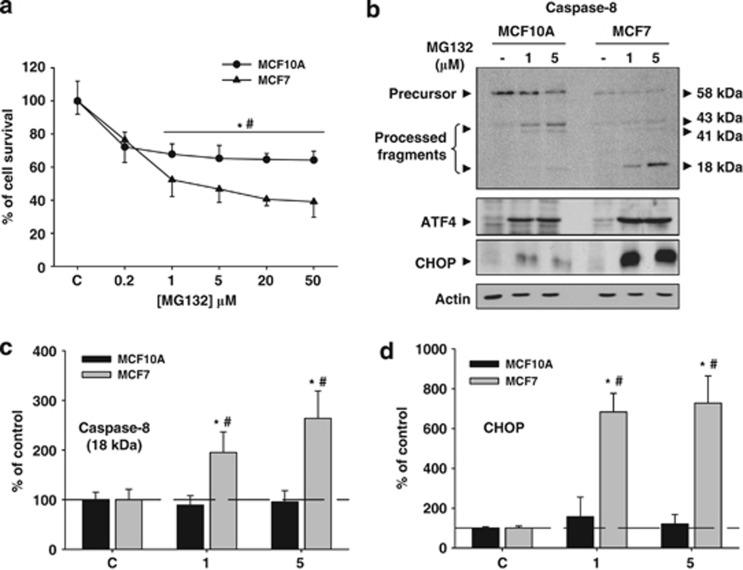

MCF7 are more vulnerable than MCF10A cells to cytotoxicity induced by acute PI

We next analyzed how PI affected cell survival. For that, proteasome activity was inhibited with MG132 for 24 h, and then cell viability was analyzed by sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay. Cell viability was similarly affected with lower dose tested in both cell lines (Figure 2a). However, higher concentrations of MG132 significantly decreased the cell viability in MCF7 but not in MCF10A cells (P<0.05), indicating that MCF7 cells were more sensitive to PI. Then, we studied the expression of molecular markers corresponding to the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic pathways, in addition to markers of the unfolded protein response (UPR). Caspase-8 was highly processed in MCF7, but not in MCF10A cells (Figure 2b, upper panel and 2c). However, caspase-9 was not processed in any of both cell types (data not shown). By contrast, components of the UPR-PERK pathway such as the transcription factor activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) was increased in both cell types, but the pro-apoptotic transcription factor CHOP, under control of ATF4, was strongly upregulated in MCF7, but weakly in MCF10A cells (Figure 2b, lower panel and 2d). Importantly, autophagy inhibition with 3-methyladenine mostly abolished CHOP expression (Figure 3a), supporting that CHOP induction is more dependent on autophagy activation than on PI. Moreover, cell death induced by PI was almost abolished in Atg5 small interfering RNA (siRNA) MCF7 cells when compared with control siRNA MCF7 cells (Figure 3b), supporting that autophagy is a potential mechanism underlying cell death induced by PI in MCF7 cells.

Figure 2.

PI has a different effect on cell viability in MCF10A and MCF7 cells. (a) Graph representation of SRB assays performed in MCF10A and MCF7 cells using increasing doses of MG132. Note the higher sensitivity of MCF7 cells to PI. (b) Molecular analysis of caspase-8 (upper panel), ATF4 (middle panel) and CHOP (lower panel) expressed in MCF10A and MCF7 cells in control condition and 24 h after PI (1 and 5 μM of MG132). Note the higher processing of caspase-8 and the strong expression of CHOP in MCF7 cells. (c and d) Graphs show quantification of active fragments of caspase-8 (18 kDa) and CHOP, respectively. Data are presented as mean±S.D. of three independent experiments done in parallel. *P<0.05, significant differences compared with control condition. #P<0.05, significant differences compared with MCF10A cells

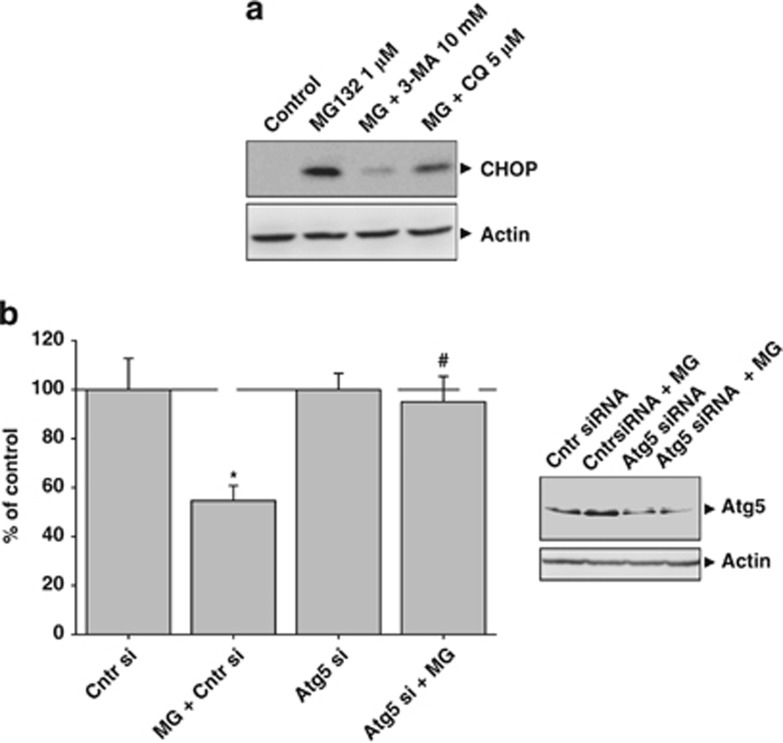

Figure 3.

Effects of autophagy inhibition in MCF7 cells subjected to PI. (a) Autophagy initiation or autophagy completion were inhibited using 10 mM of 3-methyladenine or 5 μM of chloroquine, respectively, and the expression of the pro-apoptotic transcription factor CHOP was analyzed in MCF7 cells. Note the very low expression of CHOP in cells cotreated with MG132 and 3-MA. (b) Cell viability assay in Atg5 knockdown MCF7 cells. Control siRNA cells, or control siRNA cells treated with 1 μM MG132 for 24 h, or Atg5 siRNA cells, or Atg5 siRNA cells treated with 1 μM MG132 for 24 h, were subjected to SRB cell viability assay. Data are presented as mean±S.D. of four independent experiments done in parallel. *P<0.05, significant difference compared with control condition. #P<0.05, significant difference compared with control MCF7 cells treated with MG132 1 μM

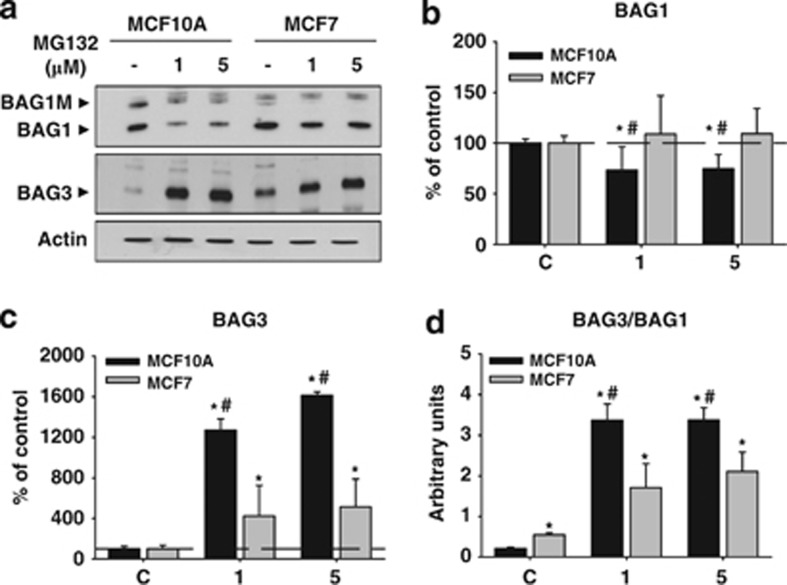

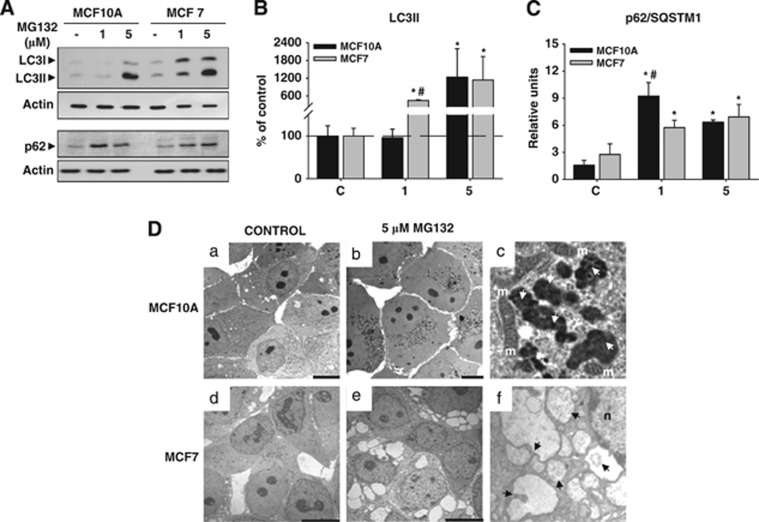

PI induces autophagy activation in MCF7 but formation of inclusion bodies in MCF10A cells

We further investigated the cellular response induced by PI by performing a molecular analysis in both cell types. On the basis of previous data, we used 1 μM and 5 μM of MG132. We focused on the expression of BAG1 and BAG3 proteins. Regarding BAG1, we only analyzed the BAG1 isoform (∼36 kDa) because it was the most abundantly expressed in both cell types. In MCF10A, BAG1 expression decreased following PI (P<0.05), whereas in MCF7 cells it remained similar to the control condition (Figures 4a and b). By contrast, BAG3 was massively upregulated in both cell types (Figures 4a and c; P<0.05), and consequently, the BAG3/BAG1 ratio was significantly increased (P<0.05). To test whether PI shifted towards autophagy degradation, as the BAG3/BAG1 ratio suggested, we analyzed the expression of two crucial proteins involved in the induction and execution of autophagy. The autophagosome marker LC3II was increased after PI in both cell types, but with different dynamics. In MCF10A, autophagosome marker LC3II only augmented with the higher dose of MG132 (P<0.05), whereas in MCF7 cells it increased in a dose-dependent manner (P<0.05). The expression of p62/SQSTM1, the protein acting as a cargo receptor for the degradation of ubiquitinated protein by autophagy,14 increased at both doses in MCF10A (Figures 5A and C; P<0.05), peaking at the lower dose, whereas in MCF7 cells it augmented in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 5A and C; P<0.05). Thus, we speculate that MCF7 cells are more dependent on autophagy activity, whereas MCF10A cells are more dependent on proteasome degradation and need a stronger PI to activate autophagy. To prove directly this supposition, we performed an ultrastructural analysis using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). In control condition, we did not observe any relevant differences between both cell types (Figures 5Da and d). However, the morphological features induced by PI were completely different. On one hand, MCF10A cells accumulated electron-dense structures around the nucleus that increased in number and size in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5Db). These aggregated-like structures were membrane-free and were surrounded by numerous mitochondria (Figure 5Dc). The presence of multilamellar structures resembling autophagolysosomes was never observed in these cells. On the other hand, tumor cells MCF7 displayed a significant cytoplasmic vacuolization that increased also in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5De). These cytoplasmic structures were different in size and showed a heterogeneous content that corresponded to digestion products (Figure 5Df). Importantly, the presence of inclusion bodies was never observed in MCF7 cells. To test whether these cytosolic vacuoles could correspond to autophagolysosomes, we used acridine orange for acidic vesicle organelles detection.15 As shown in Supplementary Figure 1A, the number of acidic vesicles labeled with acridine orange increased in a dose-dependent manner in MCF7 but not in MCF10A cells, indicating a higher biogenesis of lysosomes and/or autophagolysosomes induced by PI in tumor cells. Moreover, to determine whether the accumulation of LC3II induced by PI in MCF7 cells is caused by stimulation of autophagy or inhibition of autophagic vesicle turnover, we performed both morphological and biochemical analysis. Ultrastructural analysis performed following PI (MG132 1 μM) revealed the presence of features of autophagy activation such as abundant lysosomes, concentric double-membrane structures and cytosolic vacuoles containing digestion products (Supplementary Figure 1B). Moreover, PI in MCF7 cells in the absence or presence of chloroquine 5 μM showed a higher LC3II accumulation in the presence of chloroquine, supporting autophagy flux (Supplementary Figure 1C). These results indicate that restoration of cellular homeostasis occurred in two different ways in both cell types: MCF7 overactivated basal autophagy, whereas MCF10A induced the formation of inclusion bodies.

Figure 4.

BAG1 and BAG3 proteins are differentially affected by PI in MCF10A and MCF7 cells. (a) Representative western blot corresponding to the BAG1 (upper panel) and the BAG3 (lower panel) proteins expressed in MCF10A and MCF7 cells in control condition and after 24 h of PI. Note the decreased expression of BAG1 in MCF10A. (b and c) Graphs show BAG1 and BAG3 quantification, respectively. Data are presented as mean±S.D. of three independent experiments done in parallel. (d) Graph representing the BAG3/BAG1 ratio in MCF10A and MCF7 cells in control condition and 24 h after PI (1 and 5 μM of MG132). *P<0.05, significant differences compared with control condition. #P<0.05, significant differences compared with MCF10A cells

Figure 5.

Molecular and ultrastructural analysis of autophagic markers induced by PI in MCF10A and MCF7 cells. (A) Representative western blot shown in MCF10A and MCF7 cells, in control condition and after 24 h of PI the expression of LC3I and LC3II (upper panel) and p62 (lower panel) proteins, respectively. Note the dose-dependent expression of LC3II and p62 in MCF7 cells. (B and C) Graph representation of data from western blots similar as shown in (a). Data are presented as mean±S.D. of four independent experiments done in parallel. (D) TEM of MCF10A and MCF7 cells in control condition ((a) and (d), respectively) and 24 h after PI (5 μM of MG132; (b and e)). Note the presence of inclusion bodies in MCF10A cells (b) and the cytoplasmic vacuolization in MCF7 cells. (e) In (c) and (f) are shown magnifications of inclusion bodies (white arrows) and autophagic vacuoles with digestion products inside (black arrows), respectively. m, mitochondria; *P<0.05, significant differences compared with control condition; #P<0.05, significant differences compared with MCF10A cells. Scale bar 10 μm

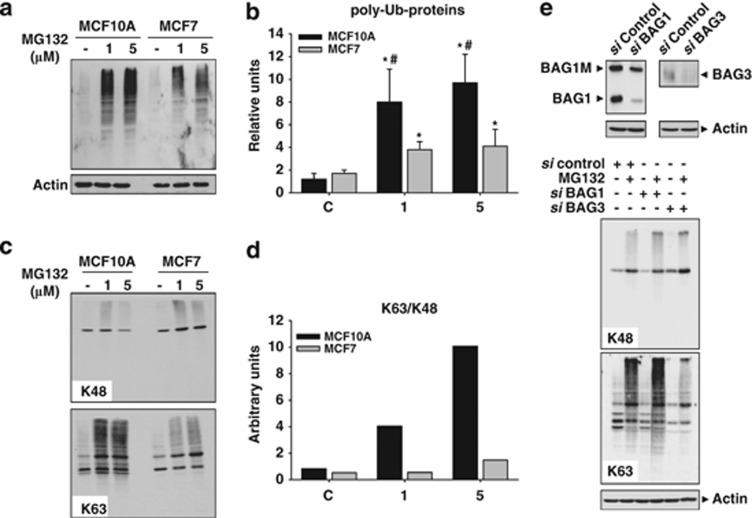

PI promotes the accumulation of K63-ubiquitinated proteins, preferentially in MCF10A

Cellular inclusions are enriched in K63-ubiquitinated proteins.16, 17, 18 Thus, we investigated the topology of ubiquitin linkages in MCF10A and MCF7 cells. First, we quantified total poly-ubiquitinated proteins accumulated, following PI. As shown in Figures 6a and b, the accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated proteins was higher in MCF10A than in MCF7 cells. Interestingly, the linkage ubiquitin topology was little different in both the cell types. In MCF10A, PI preferentially accumulated K63-ubiquitinated proteins, whereas MCF7 accumulated both K48- and K63-ubiquitinated proteins (Figure 6c). In consequence, the K63/K48 ratio augmented in a dose-dependent manner in MCF10A, but remained quite similar in MCF7 cells (Figure 6d). Importantly, ubiquitination profile was somehow regulated by BAG1 and BAG3 proteins. Indeed, PI in MCF10A cells transfected with BAG1 or BAG3 siRNAs slightly increased or severely decreased the content of K63-ubiquitinated proteins, respectively (Figure 6e). Thus, PI promotes the formation of protein inclusions enriched in K63-ubiquitinated proteins in MCF10A cells, whereas in MCF7 induces autophagic activity avoiding the formation of those inclusions.

Figure 6.

Profile of protein ubiquitination induced by PI in MCF10A and MCF7 cells. (a) Representative western blot of poly-ubiqutinated proteins in control condition and after 24 h of PI in MCF10A and MCF7 cells. (b) Graph representation of data from western blots similar as shown in (a). Data are presented as mean±S.D. of four independent experiments done in parallel. (c) Ubiquitinated proteins on K48 (upper panel) and K63 (lower panel) in control condition and 24 h after PI (1 and 5 μM of MG132), in MCF10A and MCF7 cells. Note the accumulation of K63-ubiquitinated proteins in MCF10A cells, versus the dose-dependent increase in MCF7 cells. (d) In the graph is shown the K63/K48 ratio obtained from western blots similar as shown in (c). Experiments were done in parallel and repeated at least three times with similar results. (e) MCF10A cells were transfected with BAG1 siRNAs (100 nM), BAG3 siRNAs (100 nM) or negative control siRNAs (100 nM) for 48 h, and then subjected to PI (1 μM of MG132) for 24 h. Controls of silencing are shown at the top. Ubiquitinated proteins on K48 (upper panel) and on K63 (lower panel) are shown. Note the PI-induced increase in the amount of K48 ubiquitinated proteins in cells transfected with BAG1 siRNAs and the strong decrease in the amount of ubiquinated proteins on K63 induced by PI in cells transfected with BAG3 siRNAs. *P<0.05, significant differences compared with control condition; #P<0.05, significant differences compared with MCF10A cells

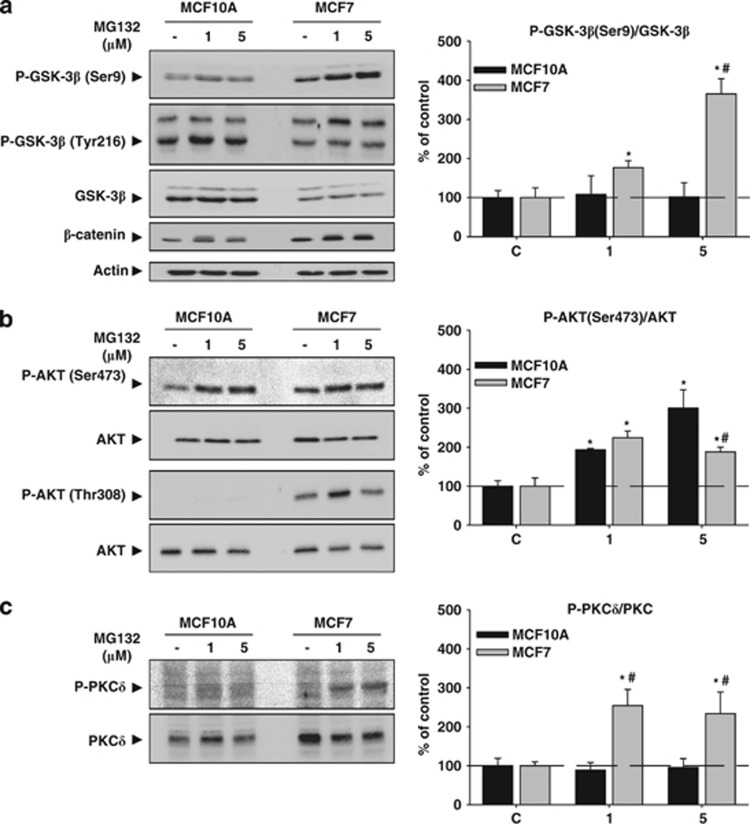

GSK-3β is inhibited in MCF7 but fully activated in MCF10A cells, following PI

We next tried to identify additional pathways that could account for the different response induced by PI in both cell types. As GSK-3β inactivation has been demonstrated to participate in autophagy activation and cell death under stress situation,19 we focused our attention on the Akt/GSK-3 pathway. As shown in Figure 7a, PI increased in a dose-dependent manner GSK-3β phosphorylation on Ser9 in MCF7, but not in MCF10A cells. Thus, GSK-3β was specifically inactivated in the tumor cells but remained active in MCF10A cells. To test whether this was related to the tumorigenic origin of cells, we used a transformed isogenic cell line of the MCF10A cells, named MCF10A-NeuT, which constitutively expresses an active form of the oncogene ErbB2/HER-2/NeuT.20 PI produced both a higher GSK-3β phosphorylation on Ser9 and accumulation of LC3II in MCF10A-NeuT cells. This behavior was similar to that observed in MCF7 cells (Supplementary Figure 1D), indicating that differential regulation of GSK-3β by PI seems to be related with the tumorigenic origin of these cells. Moreover, MCF10A but not MCF7 cells augmented phosphorylation of GSK-3β on Tyr216, leading to a higher activity of this kinase (Figure 7a, middle). The lower activity of GSK-3β was reflected in the accumulation of β-catenin, exclusively in MCF7 cells (Figure 7a, lower part). Interestingly, the behavior of GSK-3α was also opposed in both cell types after PI (Figure 7a). Next, we analyzed both Akt and protein kinase C (PKC)δ phosphorylation, two kinases that phosphorylate GSK-3β on Ser9.21 PI increased phosphorylation of Akt on Ser473 in both cell types, being the ratio of P-Akt/Akt higher in MCF10A than in MCF7 cells using MG132 5 μM (Figure 7b upper panel P<0.05). By contrast, the phosphorylation on Thr308 was exclusively detected in MCF7 cells in both, basal condition and following PI (Figure 7b lower panel). Similarly, PI induced phosphorylation of PKCδ in MCF7 but not in MCF10A cells (Figure 7c). These data indicate that PI induces an inverse regulation of signaling pathways involving GSK-3β in both cell lines.

Figure 7.

Akt/GSK-3β response induced by PI in MCF10A and MCF7 cells. (a) MCF10A and MCF7 cells were treated with MG132 (1 and 5 μM) for 24 h, and then the amount of GSK-3β phosphorylated on Ser9 (upper panel) and on Tyr216 (middle panel) was analyzed. Note the dose-dependent increase of GSK-3β phosphorylated on Ser9 in MCF7 cells but not in MCF10A cells. The contrary was observed for GSK-3β phosphorylated on Tyr216. The amount of total GSK-3β was higher in MCF10A than in MCF7 cells, but PI did not modify its expression in any cell type. On the right is shown the quantification of the ratio between GSK-3β phosphorylated on Ser9 and GSK-3β in both cell types. The lower panel shows the β-catenin expression. Note the higher amount of β-catenin in MCF7 cells. (b) Similar as in (a), but analyzing Akt phosphorylated on Ser473 (upper panel) and on Thr308 (lower panel). Note the absence of Akt phosphorylated on Thr308 in MCF10A cells. On the right is shown the quantification of the ratio between Akt phosphorylated on Ser473 and Akt in both cell types. (c) Phosphorylated PKCδ and PKCδ expression in both cell types as well as quantification of the ratio between phosphorylated PKCδ and PKCδ (graph on the right). Note the higher basal expression of PKCδ and the dose-dependent increase of phosphorylated PKCδ in MCF7 cells versus the absence of it in MCF10A cells. *P<0.05, significant differences compared with control condition; #P<0.05, significant differences compared with MCF10A cells

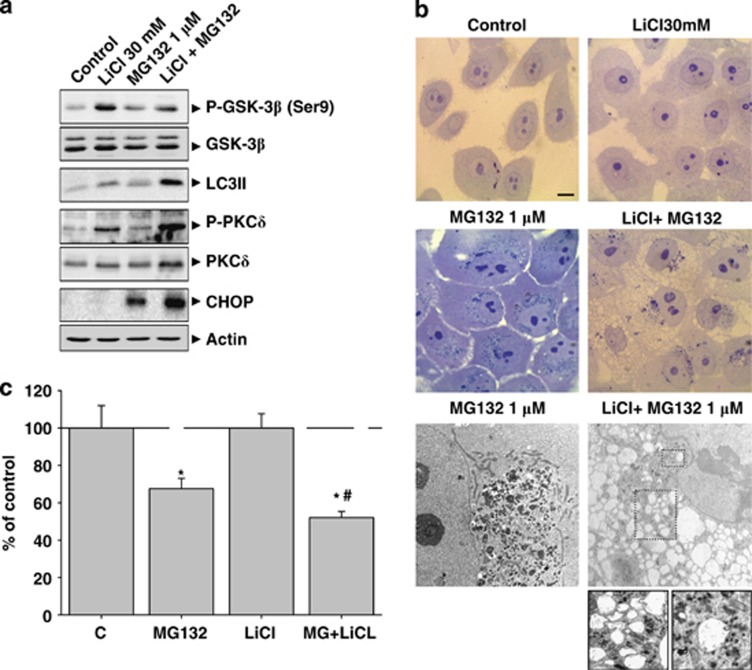

Autophagy activation induced by PI is dependent on GSK-3β inactivation in MCF10A cells

To investigate whether GSK-3β inhibition and autophagy activation were causally related, we inhibited GSK-3β activity using lithium chloride (LiCl) and induced PI in MCF10A cells, which neither activated autophagy nor inhibited GSK-3β. As shown in Figure 8a, treatment with LiCl sensitized MCF10A cells to PI (MG132 1 μM; see Figure 5). As expected, LiCl (30 mM) increased Ser9 phosphorylation in GSK-3β. Furthermore, the level of LC3II was slightly higher because of the transcriptional activation of the LC3 gene (data not shown). A similar effect was obtained using the specific GSK-3β inhibitor VII (Supplementary Figure 1E). Moreover, LiCl augmented the phosphyorylation of PKCδ (Figure 8a), but not Akt phosphorylation (data not shown). Under this situation, PI strongly increased either the level of LC3II, the phosporylation of PKCδ as well as CHOP expression. Cotreatment with LiCl and MG132 induced morphological changes in the cytoplasm of MCF10A cells, which were different to that observed in cells treated with MG132 alone. As previously shown, PI induced the formation of inclusion bodies without the evidence of autophagy activation (Figure 8b). However, the combination of LiCl and MG132 produced a high cytoplasmic vacuolization with minimal cytosolic aggregation (Figure 8b). Electron microscopy revealed the presence of inclusion bodies in MCF10A cells treated with MG132, but cytosolic vacuoles in cotreated MCF10A cells (Figure 8b lower panel). Some of these vacuoles were observed surrounding cytosolic aggregates (magnification in Figure 8b), showing heterogeneous content that may correspond to digestion products. These data strongly support that GSK-3β inhibition is necessary for autophagy activation. As autophagy inhibition decreased cell death induced by PI in MCF7 cells (Figure 3b), we investigated whether autophagy activation could increase cell death in MCF10A. As shown in Figure 8c, PI in the presence of LiCl significantly increased cell death compared with PI alone.

Figure 8.

Cotreatment with LiCl and MG132 increases autophagy activity and rise up the rate of cellular death in MCF10A cells. (a) MCF10A cells were treated with MG132 (1 μM), LiCl (30 mM) or both for 24 h, and then different molecular markers were analyzed. Note the higher increase of LC3II, phosphorylated PKCδ and CHOP in cotreated cells. (b) Upper panel; optical microscope photographs of control, LiCl, MG132 and cotreated MCF10A cells. Note the presence of inclusion bodies in proteasome inhibitor-treated cells and the presence of cytoplasmic vacuoles in cotreated MCF10A cells; lower panel. Electron microscopic detection of inclusion bodies in proteasome inhibitor-treated cells (left panel), and autophagic vacuoles in cotreated cells (right panel). (c) Cell viability assay in MCF10A cells. Untreated cells, or cells treated with 30 mM LiCl, 1 μM MG132 or both for 24 h, were subjected to SRB cell viability assay. Data are presented as mean±S.D. of three independent experiments done in parallel. Scale bar 10 μm. *P<0.05, significant differences compared with control condition; #P<0.05, significant differences compared with MG132 or LiCl treatments

Discussion

We have characterized the two major cellular pathways involved in protein degradation in MCF10A and MCF7 cells. The study was carried out in both, basal and proteasome stress situations. In basal condition, MCF7 cells showed a lower proteasome activity that could be due, at least in part, to the absence of immunoproteasomes. The downregulation of immunoproteasome could benefit cancer cells by inhibiting antigen presentation, which in turn, could constitute an immune evasion strategy for some tumor types. The absence or reduced expression of immunoproteasomes has been previously described in other tumor cell lines.22, 23, 24, 25, 26 Thus, our results support the idea that immunoproteasome represents a promising prospect for certain tumors including breast cancer. The lowering of proteasome activity seems to be compensated by a higher autophagy activity. A growing body of evidence suggests that basal autophagy has a relevant homeostatic role in maintaining protein and organelle quality control, acting in parallel with the UPS to prevent accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated and aggregated proteins.7, 27 Therefore, our results are in line with this idea. Although molecular links between both proteolytic systems are not completely understood, BAG1 and BAG3 have an important role in regulating both processes.28, 8, 9, 11 BAG3 was overexpressed in MCF7 cells in basal condition, whereas its expression was residual in MCF10A cells. Importantly, differences in the proteolytic systems in basal condition determined the response to PI in both cell types. On one hand, cell mortality was higher in tumor cells than in non-tumor cells, and on the other hand the homeostatic response was completely different in both cell types. Biochemical data demonstrated that MCF7 cells did not modify the expression of BAG1 and coordinately upregulated, in a dose-dependent manner, the expression of BAG3, p62/SQSTM1 and LC3II. By contrast, MCF10A cells downregulated the expression of BAG1, but also upregulated BAG3, p62/SQSTM1 and LC3II, although with different dynamics and sensitivity to PI. These molecular differences were also reflected at the cellular level. Ultrastuctural analysis revealed that MCF7 cells showed profuse autophagy activation with none or minimal cytosolic inclusions, whereas MCF10A cells presented aggresome-like structures, without evidence of autophagy activation. Sequestration of aggregated proteins is classically considered a cellular response that occurs once the refolding capacity and degradation of soluble misfolded proteins are overpassed.29 Thus, our results indicated that tumor cells are more dependent on the autophagy, whereas non-tumor cells seem to be more dependent on the proteasome. Sequestration of misfolded proteins in MCF10A cells has a protective role in this context.

Autophagy is considered a non-selective degradative system, but growing evidence support the existence of selective autophagy that specifically targets protein aggregates for their clearance.30 In this sense, the ubiquitination pattern of proteins targeted for degradation could determine whether adapter proteins will bring them to the autophagosomes or to the proteasome.31, 32, 18 We demonstrated that dynamics of ubiquitinated proteins induced by PI was somehow different in both cell types. The K63/K48 ratio increased in a dose-dependent manner in MCF10A but not in MCF7 cells. Ubiquitination on K48 is considered a signal for proteasome degradation, whereas ubiquitination on K63 preferentially destines proteins to the autophagy—lysosomal pathway.3, 31 However, it has also been described that K63-ubiquitinated proteins are more prone to form intracellular inclusions.17, 18 On the other hand, the role of p62/SQSTM1 in the biogenesis of intracellular protein aggregates is well documented. This stress-regulated multi-adaptor protein binds to both aggregated poly-ubiquitinated proteins, preferentially on K63 and LC3.33, 14, 16, 31, 34 Moreover, it is well established that p62/SQSTM1 regulates inclusion body formation and degradation by autophagy.35, 36 Thus, we speculate that electron-dense structures induced by PI in MCF10A cells might agglutinate K63-ubiquitinated proteins, in addition to p62/SQSTM1, BAG3 and LC3. However, we cannot discard that other proteins showing different patterns of ubiquitination, or even non-ubiquitinated proteins, might take part in these intracellular inclusions. A similar situation could be operating in the tumor cells MCF7. However, because of the faster autophagy activation, probably due to the higher basal activity, protein accumulation and autophagy overactivation are better synchronized, avoiding protein accumulation. At this point, a relevant question is to know the molecular mechanisms underlying the different homeostatic responses in both cell types. We show strong evidence indicating that it somehow depends on GSK-3β activity. Indeed, GSK-3β was inversely regulated in both cell types following PI (inhibited in a dose-dependent manner in tumor cells and fully activated in non-tumor cells). Moreover, dose-dependent inactivation of GSK-3β was paralleled by dose-dependent activation of autophagy in MCF7 cells, and most importantly, autophagy activation in MCF10A cells only occurred when proteasome and GSK-3β were simultaneously inhibited. Under this situation, most of the molecular and morphological features induced by PI in MCF7 cells were reproduced in cotreated MCF10A cells such as, accumulation of LC3II, increased PKCδ phosphorylation, higher CHOP expression, extensive vacuolization with minor inclusion bodies and higher cell death. Thus, our results are in line with the recent data indicating that GSK-3β has a relevant role in regulating autophagy activity in tumor cells under stress situations.19, 37 Under ER-stress, cells activate a signaling pathway called UPR that is mediated by the sensor proteins PERK, IRE1α and ATF6, in order to mitigate the cellular stress.38 The UPR and autophagy activation are two linked phenomena.39, 40 In particular, PERK pathway mediates transcriptional activation of LC3, Atg5 and Atg12 genes by the transcription factors ATF4 and CHOP.41, 42, 43 In this sense, we observed strong upregulation of ATF4 and mostly CHOP in MCF7, but not in MCF10A cells, following PI. However, in MCF10A subjected to both GSK-3β and PI, CHOP expression increased even more, similarly as observed in MCF7 cells. Finally, caspase-8 has also been linked to autophagy activation44, 45, 46, 47 and autophagy activity is necessary for cleavage of caspase-8 induced by PI.48, 19 Thus, the higher processing of caspase-8 in MCF7 cells in both, basal- and proteasome stress situations might represent an additional factor that contributes to the higher basal autophagy activity in the tumor cell line MCF7.

Collectively, our findings strongly argue for the induction of autophagy as the main way to restore cell homeostasis under proteasome stress situation in the human breast cancer cells, MCF7. Moreover, we provide solid evidence supporting that efficient autophagy activation in response to PI is dependent on GSK-3β. This finding is in line with a recent work, demonstrating that GSK-3β inhibition promoted lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy protein degradation.49 Finally, we also show that autophagy has an active role on cell death in the tumor cell line MCF7 subjected to proteasome stress. However, we cannot discard the possibility that autophagy activation in response to PI might be initially a prosurvival process in an attempt to keep cells alive, but with fatal collateral consequences.

Materials and Methods

Cells and culture conditions

The study was carried out in an ER+ human epithelial breast cancer cell line, MCF7 and in a human epithelial-non tumorigenic breast cell line, MCF10A (American Type Culture Collection). MCF7 cells were cultured in DMEM/Ham's F12 (1/1) medium (PAA Laboratories, Piscataway, NJ, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Alcobendas, Spain), 2 mM ℒ-glutamine, 50 μg/ml streptomycin and 50 U/ml penicillin (Sigma-Aldrich, Madrid, Spain). The human mammary epithelial cells MCF10A and the transformed cell lines MCF10A-NeuT (oncogen ErbB2/HER-2/NeuT constitutively expressed) and MCF10A-pBabe (empty plasmid) were grown in DMEM/Ham's F12 (1/1) medium (PAA Laboratories) supplemented with 10% (v/v) horse serum (Gibco), 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, 50 U/ml penicillin, 2.5 mg/ml insulin, 150 μg/ml cholera enterotoxin (Sigma-Aldrich), 2.5 mg/ml hydrocortisone and 50 μg/ml epidermal growth factor (Calbiochem, Billerica, MA, USA). Both cell lines were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Cells were routinely subcultured and they were always in exponential growth phase when used for experiments. Each experiment was independently performed at least in triplicate.

Treatments and drugs

Both cell lines were treated in parallel with the reversible proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Sigma-Aldrich), at doses indicated in the figures during 24 h. Cells were also treated with 30 mM of LiCl for 24 h (Sigma-Aldrich) or 20 μM of GSK-3β inhibitor VII (Calbiochem) for GSK-3β inhibition. Treatments were carried out alone or in combination.

Proteasome activity assay

Chymotrypsin-like activity was determined using 50 μM of Suc-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-aminomethylcoumarin (AMC; Sigma-Aldrich) as substrate, as previously described.50 Assay mixtures containing 10 μg of protein, substrate and 50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, was made up in a final volume of 100 μl. Measures were performed at 37 °C, by monitoring fluorescence emission (excitation wavelength 380 nm, emission wavelength 460 nm) on a Thermo Scientific Varioskan Flash Spectral Scanning Multimode Reader (software Scanlt, version 2.4.1, Alcobendas, Spain). The fluorescence emission was first determined 2 min after substrate incubation and then every 15 min during a total incubation period of 75 min. The product formation was linear during this time. Triplicate assays were performed for MCF10A and MCF7 cells, and determinations were always performed in parallel. Activity was calculated by comparing the slopes of the line obtained by plotting fluorescence versus the time of incubation. Background activity was determined by addition of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Sigma-Aldrich), at a final concentration of 10 μM.

Sulforhodamine B assay

To assay cell viability, cells in exponential growth phase were harvested using trypsin-EDTA (Gibco), and resuspended in their respective media. Cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 103 cells/100 μl in a 96-well microtiter plate (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) and then allowed for 24 h to attach and grow. Then, they were incubated further for 24 h in the presence of proteasome inhibitor MG132. The concentration range tested (200 nM–50 μM) was prepared in a culture medium from a stock solution in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich). Following the recommendations of the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD, USA), the analysis of cytotoxic effects induced by MG132 was determined using a cell growth assay, the SRB (Sigma-Aldrich) assay, as previously described.51, 52 Briefly, 50 μl per well of cold 50% trichloroacetic acid (TCA; final concentration 10%) was added to the culture and incubated at 4 °C for 1 h, to precipitate the proteins and fix the cells. The supernatant was then discarded, and the plates were washed five times with distilled water and air-dried. The cells were then stained with 100 μl per well of 0.4% SRB dissolved in 1% acetic acid for 30 min at room temperature. Unbound SRB was removed by washing five times with 1% acetic acid, and then plates were air-dried. The stained protein was solubilized in 100 μl per well of 10 mM Tris Base, pH=8.7 by shaking. The optical density was read at 515 nm using a microtiter plate reader (ELISA).

Acridine orange staining

As a marker of autophagy the cellular acidic compartments can be visualized by acridine orange staining. Cells were seeded on coverslips in the absence or in the presence of MG132 (1 or 5 μM, for 24 h). Then cells were washed with PBS and incubated for 10 min with medium containing 0.1 μg/ml acridine orange (Molecular Probes, Alcobendas, Spain). The acridine orange was removed by washing coverslips with PBS (for 5 min three times). Fluorescent images were taken using a fluorescent microscope (Olympus BX61, Barcelona, Spain).

Western blotting

Immunoblots were done as previously described.50 Briefly, proteins were loaded on a 12 or 14% polyacrylamide gel for electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE; Bio-Rad, Alcobendas, Spain) and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond-C Extra; Amersham, Barcelona, Spain). After blocking, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C, with the following primary antibodies: (i) rabbit polyclonal antibodies against: Akt, phospho-Akt(S473), phospho-Akt(T308), Atg5, Atg7, Beclin-1, Caspase-9, Cleaved Caspase-8, LC3B, phospho-GSK-3β(S9) and SQSTM1/p62 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA); BAG1 (c-16), Proteasome 20S alpha2 subunit (H-120; Santa Cruz Biotech, Heidelberg, Germany). P-GSK-3α(Y279)/β(Y216; Invitrogen, Alcobendas, Spain); Ubiquitin (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark); Proteasome 20S alpha+beta, Proteasome 20S β5i/LMP7 and Proteasome 20S β1i/LMP2 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK); K48-linkage Specific poly-ubiquitin Antibody (Cell Signaling) and K63-linkage Specific poly-ubiquitin (D7A11; Cell Signaling); (ii) mouse monoclonal antibodies against: β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich); CHOP (Cell Signaling); GSK 3-clone 4G-1E (Millipore, Madrid, Spain); ATF4 (Abcam) and (iii) goat polyclonal antibody against BAG3 (P-17) (Santa Cruz Biotech). Then, membranes were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody (Dako) horseradish peroxidase-conjugated, at a dilution of 1/10000 and developed using the ECL-plus detection method (Amersham) and the ImageQuant LAS 4000 MINI GOLD (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Barcelona, Spain). For quantification, the optical density of individual bands was analyzed using PCBAS 2.08 software (Raytest Inc, Berlin, Germany), and the optical density of each band was normalized relative to the optical density of β-actin.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription

For PCR analysis, total RNA was extracted using the Tripure Isolation Reagent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The recovery of RNA was similar between MCF10A and MCF7 cells. Reverse transcription was performed using random hexamers primers exactly as previously described.53

Real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR

cDNAs were diluted in sterile water and used as template for the amplification by the PCR. Optimization and amplification of each specific gene product was performed using the ABI Prism 7000 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems, Barcelona, Spain) and TaqMan probes designed by Applied Biosystems, as previously described.50 The cDNA levels of the different cell types were determined using two different housekeepers (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and β-actin). The amplification of the housekeepers was done in parallel with the gene to be analyzed. Similar results were obtained using both housekeepers. Thus, the results were normalized using both β-actin and GAPDH expression. Threshold cycle (Ct) values were calculated using the software supplied by Applied Biosystems.

Small interfering RNA

MCF10A and MCF7 cells were transfected during 48 h with 100 nM of siRNA using Dharma-FECT 1 siRNA transfection reagent (Dharmacon, Madrid, Spain). MCF10A cells were transfected with BAG1 siRNA FlexiTube GeneSolution (GS573) or BAG3 siRNA FlexiTube GeneSolution (GS9531). MCF7 cells were transfected with Atg5 siRNA FlexiTube GeneSolution (GS9474). Control cells were transfected with AllStars Negative Control siRNA. All siRNA were purchased from Qiagen, Las Matas, Spain.

Transmission electron microscopy

Cell monolayers were fixed in 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate-HCl buffer pH=7.4 for 1 h at 4 °C. Cells were rinsed in cacodylate buffer twice and incubated for 1 h at 4°C in 1% (v/v) OsO4/1% (w/v) K4Fe(CN)6 in cacodylate buffer pH=7.4. Cells were rinsed again in cacodylate buffer and finally in distilled water. Then, cells were stained with 1% (w/v) aqueous uranyl acetate for 2 h at 4 °C. After washing with distilled water, they were dehydrated through increased graded ethanol series and embedded in Epon resin 812 (Sigma-Aldrich, Tres Cantos, Spain). Ultrathin sections were stained with lead citrate for 5 min. Toluidine blue-stained 0.5 μm semithin sections were used as control. All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean±S.D. All our data fit significantly to a normal distribution according to a standardized Kurtosis test. The differences between groups were measured using a one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey test. The significance was set at 95% confidence intervals. Significant differences are referenced as P<0.05 in the text. Statistical analysis was done using the statgraphics plus (v 3.1) program, Warrenton, VA, USA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Remedios García Navarro for her technical assistance in TEM, Modesto Carballo Álvarez and Juan Luis Ribas Salgueiro from CITIUS for their technical assistance in proteasome activity meassurement and fluorescent microscopy. The MCF10A-NeuT and MCF10A-pBabe cell lines were provided by Dr. Abelardo López Rivas from CABIMER. This work was supported by Grant no. PS09/00848 and PI12/00445 (DR) from the Carlos III Health Institute, Spain. EG is supported by a contract from JA.

Glossary

- 3-MA

3-methyladenine

- Akt (PKB)

protein kinase B

- ATF4

activating transcription factor 4

- Atg

autophagy-related genes

- BAG

Bcl-2-associated athanogene

- CHOP (GADD153)

growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible gene 153

- Cntr, C

control

- CQ

chloroquine

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GSK-3

glycogen synthase kinase-3

- HER-2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HLA

human leukocyte antigens

- IFN-γ

interferon-gamma

- LC3

microtubule-associated protein light chain 3

- LiCl

lithium chloride

- LMP2

proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, β-type 9 (large multifunctional peptidase 2)

- LMP7

proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, beta type 8 (large multifunctional peptidase 7

- Lys, K

lisina

- MCF

Michigan Cancer Foundation

- MG132, MG

carbobenzoxy-leu-leuleucinal

- PKC

protein kinase C

- poly-Ub

poly-ubiquitinated

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase-PCR

- siRNA, si

small interfering RNA

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- UPS

ubiquitin-proteasome system

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by A Stephanou

Supplementary Material

References

- Jung T, Catalgol B, Grune T. The proteasomal system. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30:191–296. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechsteiner M, Hill CP. Mobilizing the proteolytic machine: cell biological roles of proteasome activators and inhibitors. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komander D. The emergin complexity of protein ubiquitination. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:937–953. doi: 10.1042/BST0370937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaczynska M, Rock KL, Goldberg AL. Gamma-interferon and expression of MHC genes regulate peptide hydrolysis by proteasomes. Nature. 1993;365:264–267. doi: 10.1038/365264a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preckel T, Fung-Leung WP, Cai Z, Vitiello A, Salter-Cid L, Winqvist O, et al. Impaired immunoproteasome assembly and immune responses in PA28-/- mice. Science. 1999;286:2162–2165. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5447.2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivett AJ, Bose S, Brooks P, Broadfoot KI. Regulation of proteasome complexes by gamma-interferon and phosphorylation. Biochimie. 2001;83:363–366. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(01)01249-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamerdinger M, Kaya AM, Wolfrum U, Clement AM, Behl C. BAG3 mediates chaperone-based aggresome-targeting and selective autophagy of misfolded proteins. EMBO rep. 2011;12:149–156. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamerdinger M, Hajieva P, Kaya AM, Wolfrum U, Hart FU, Behl C. Protein quality control during aging involves recruitment of the macroautophagy pathway by BAG3. EMBO J. 2009;28:889–901. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama S, Reed JC. Molecular chaperone targeting and regulation by BAG family proteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:E237–E241. doi: 10.1038/ncb1001-e237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behl C. BAG3 and friends: co-chaperones in selective autophagy during aging and disease. Autophagy. 2011;7:795–798. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.7.15844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packham G, Brinimeli M, Cleveland JL. Mammalian cells express two 28. differently localized Bag-1 isoforms generated by alternative translation initiation. Biochem J. 1997;328:807–813. doi: 10.1042/bj3280807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groll M, Huber R. Inhibitors of the eukaryotic 20S proteasome core particle: a structural approach. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1695:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjørkøy G, Lamark T, Brech A, Outzen H, Perander M, Øvervatn A, et al. p62/SQSTM1 forms protein aggregates degraded by autophagy and has a protective effect on huntingtin-induced cell death. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:603–614. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, Cuervo AM, Seglen PO. Methods for monitoring autophagy from yeast to human. Autophagy. 2007;3:181–206. doi: 10.4161/auto.3678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankiv S, Hoyvarde Clausen T, Lamark T, Brech A, Bruun JA, et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24131–24145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan JM, Wong ES, Kirkpatrick DS, Pletnikova O, Ko HS, Tay SP, et al. Lysine 63-linked ubiquitination promotes the formation and autophagic clearance of protein inclusions associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:431–439. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim KL, Lim GG. K63-linked ubiquitination and neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;43:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Takahashi Y, Cheng E, Liu J, Terranova PF, Zhao B, et al. GSK-3β promotes cell survival by modulating Bif-1-dependent autophagy and cell death. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:861–870. doi: 10.1242/jcs.060475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenssen KK, Caldwell SA, Shahriari KS, Jackson SR, Whelan KA, Klein-Szanto AJ, et al. ErbB2 requires integrin alpha5 for anoikis resistance via Src regulation of receptor activity in human mammary epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1373–1382. doi: 10.1242/jcs.050906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes CA, Jope RS. The multifaceted roles of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta in cellular signaling. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;65:391–426. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(01)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen A, France J, Sy MS, Harding CV. Down-regulation of the transporter for antigen presentation, proteasome subunits, and class I major histocompatibility complex in tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3660–3667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageshita T, Hirai S, Ono T, Hicklin DJ, Ferrone S. Down-regulation of HLA class I antigen processing molecules in malignant melanoma: association with disease progression. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:745–754. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65321-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meidenbauer N, Zippelius A, Pittet MJ, Laumer M, Vogl S, Heymann J, et al. High frequency of functionally active Melan-aspecific T cells in a patient with progressive immunoproteasome-deficient melanoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6319–6326. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heink S, Fricke B, Ludwig D, Kloetzel PM, Krüger E. Tumor cell lines expressing the proteasome subunit isoform LMP7E1 exhibit immunoproteasome deficiency. Cancer Res. 2006;66:649–652. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellerhoff B, Gu S, Laumbacher B, Nerlich AG, Weiss EH, Glas J, et al. The LMP7-K allele of the immunoproteasome exhibits reduced transcript stability and predicts high risk of colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7145–7154. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft C, Peter M, Hofmann K. Selective autophagy: ubiquitin-mediated recognition and beyond. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:836–841. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carra S, Seguin SJ, Landry J. HspB8 and Bag3: a new chaperone complex targeting misfolded proteins to macroautophagy. Autophagy. 2008;4:237–239. doi: 10.4161/auto.5407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyedmers J, Mogk A, Bukau B. Cellular strategies for controlling protein aggregation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:777–788. doi: 10.1038/nrm2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim PK, Hailey DW, Mullen RT, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Ubiquitin signals autophagic degradation of cytosolic proteins and peroxisomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:20567–20574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810611105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M, Waguri S, Koike M, Sou YS, Ueno T, Hara T, et al. Homeostatic levels of p62 control cytoplasmic inclusion body formation in autophagy-deficient mice. Cell. 2007;131:1149–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari A, Chen ZJ. Diversity of polyubiquitin chains. Dev Cell. 2009;16:485–486. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibenhener ML, Babu JR, Geetha T, Wong HC, Krishna NR, Wooten MW. Sequestosome 1/p62 is a polyubiquitin chain binding protein involved in ubiquitin proteasome degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8055–8068. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8055-8068.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olzmann JA, Li L, Chudaev MV, Chen J, Perez FA, Palmiter RD, et al. Parkin-mediated K63-linked polyubiquitination targets misfolded DJ-1 to aggresomes via binding to HDAC6. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:1025–1038. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkin V, McEwan DG, Novak I, Dikic I. A role for ubiquitin in selective autophagy. Mol Cell. 2009;34:259–269. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen T, Lamark T. Selective autophagy mediated by autophagic adapter proteins. Autophagy. 2011;7:279–296. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.3.14487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi CH, Lee BH, Ahn SG, Oh SH. Proteasome inhibition-induced p38 MAPK/ERK signaling regulates autophagy and apoptosis through the dual phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;418:759–764. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.01.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavilán MP, Pintado C, Gavilán E, Jiménez S, Ríos RM, Vitorica J, et al. Dysfunction of the unfolded protein response increases neurodegeneration in aged rat hippocampus following proteasome inhibition. Aging Cell. 2009;8:654–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milani M, Rzymski T, Mellor HR, Pike L, Bottini A, Generali D, et al. The role of ATF4 stabilization and autophagy in resistance of breast cancer cells treated with Bortezomib. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4415–4423. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benbrook DM, Long A. Integration of autophagy, proteasomal degradation, unfolded protein response and apoptosis. Exp Oncol. 2012;34:286–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouschop KM, Wouters BG. Regulation of autophagy through multiple independent hypoxic signaling pathways. Curr Mol Med. 2009;9:417–424. doi: 10.2174/156652409788167131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rzymski T, Milani M, Pike L, Buffa F, Mellor HR, Winchester L, et al. Regulation of autophagy by ATF4 in response to severe hypoxia. Oncogene. 2010;29:4424–4435. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook KL, Shajahan AN, Clarke R. Autophagy and endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2011;11:1283–1294. doi: 10.1586/era.11.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boatright KM, Salvesen GS. Mechanisms of caspase activation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:725–731. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Pinedo C, Ruiz-Ruiz C, Ruiz de Almodóvar C, Palacios C, López-Rivas A. Inhibition of glucose metabolism sensitizes tumor cells to death receptor-triggered apoptosis through enhancement of death-inducing signaling complex formation and apical procaspase-8 processing. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12759–12768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212392200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes MA, Harper N, Butterworth M, Cain K, Cohen GM, MacFarlane M. Reconstitution of the death-inducing signaling complex reveals a substrate switch that determines CD95-mediated death or survival. Mol Cell. 2009;35:265–279. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Li Q, Lee JY, Lee SH, Jeong JH, Lee HR, et al. FLIP mediated autophagy regulation in cell death control. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1355–1362. doi: 10.1038/ncb1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laussmann MA, Passante E, Düssmann H, Rauen JA, Würstle ML, Delgado ME, et al. Proteasome inhibition can induce an autophagy dependent apical activation of caspase-8. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:1584–1597. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr C, Carzaniga R, Gentleman SM, Van Leuven F, Walter J, Sastre M. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibition promotes lysosomal biogenesis and autophagic degradation of the amyloid-β precursor protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:4410–4418. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00930-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavilán MP, Pintado C, Gavilán E, García-Cuervo LM, Castaño A, Ríos RM, et al. Age-related differences in the dynamics of hippocampal proteasome recovery. J Neurochem. 2012;123:635–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skehan P, Storeng R, Scudiero D, Monks A, McMahon J, Vistica D, et al. New colorimetric cytotoxicity assay for anticancer-drug screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82:1107–1112. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.13.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keepers YP, Pizao PE, Peters GJ, van Ark-Otte J, Winograd B, Pinedo HM. Comparison of the sulforhodamine B protein and tetrazolium (MTT) assays for in vitro chemosensitivity testing. Eur J Cancer. 1991;27:897–900. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(91)90142-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavilán MP, Pintado C, Gavilán E, Jiménez S, Ríos RM, Vitorica J, et al. Dysfunction of the unfolded protein response increases neurodegeneration in aged rat hippocampus following proteasome inhibition. Aging Cell. 2009;8:654–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.