Abstract

Rationale

Interventions that improve clinicians’ awareness of racial disparities and improve their communication skills are considered promising strategies for reducing disparities in health care. We report clinicians’ views of an intervention involving cultural competency training and race-stratified performance reports designed to reduce racial disparities in diabetes outcomes.

Research Design and Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 12 physicians and 5 nurse practitioners who recently participated in a randomized intervention to reduce racial disparities in diabetes outcomes. Clinicians were asked open ended questions about their attitudes towards the intervention, the causes of disparities and potential solutions to them.

Results

Thematic analysis of the interviews showed that most clinicians acknowledged the presence of racial disparities in diabetes control among their patients. They described a complex set of causes, including socioeconomic factors, but perceived only some causes to be within their power to change, such as switching patients to less expensive generic drugs. The performance reports and training were generally well received but some clinicians did not feel empowered to act on the information. All clinicians identified additional services that would help them address disparities, for example culturally tailored nutrition advice. Some clinicians challenged the premise of the intervention, focusing instead on socioeconomic factors as the primary cause of disparities, rather than patients’ race.

Conclusions

The cultural competency training and performance reports were well received by many but not all of the clinicians. Clinicians reported the intervention alone had not empowered them to address the complex, root causes of racial disparities in diabetes outcomes.

Keywords: diabetes, disparities, clinician attitudes

Despite evidence that quality improvement programs can narrow or eliminate racial disparities in process measures of diabetes care, disparities in intermediate outcomes persist.1-3 Efforts are continuing to build knowledge about methods to reduce these disparities in achievement of optimal glycemic, cholesterol, and blood pressure control in many health care settings.4-6 Many have argued that actions to address disparities should target multiple levels, including patients and their communities, providers, and the wider health care system.7-9

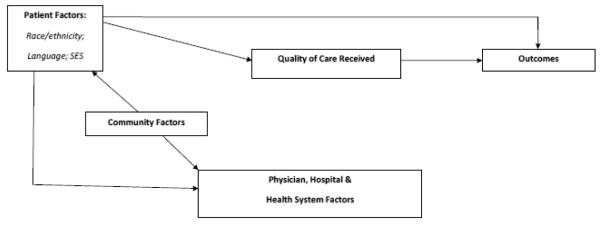

Healthcare organizations wishing to take action to reduce disparities often face an incomplete understanding of the relative importance of the factors that drive disparities in health outcomes.10 Racial disparities in quality of care are influenced by a complex interaction of patient factors, community factors, and physician factors (Figure 1).11 Within the domain of health care providers, interventions can involve an organizational response including the provision of new services, or seek to influence the knowledge and behavior of individual clinicians within the organization. The challenge for those designing interventions to improve outcomes has been to understand the importance of these potential organizational strategies relative to focusing on community or patient factors. These latter factors may have a direct impact on health outcomes, independent of the quality of health care given, in ways that may not be within the domain of health care providers.10,11

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of quality of care and outcomes by race, ethnicity, language and socioeconomic factors, adapted from Ayanian JZ, Determinants of racial and ethnic disparities in surgical care. World J Surg. 2008 32:509-51511

One potentially effective approach to reducing disparities in outcomes is to improve individual clinicians’ awareness of disparities and provide training to enable them to take action to address health care disparities within their organizations.12 The importance of working with clinicians is supported by research suggesting that patient race may play a role, perhaps at an unconscious level, in clinicians’ decision making.13-15 In addition, many clinicians may be unaware of disparities in the health care system as a whole or among their own patients.16

Provision of clinical performance feedback17 and communication tools represent two strategies to engage clinicians to address racial disparities in their local clinical environment. Efforts to understand the impact of programs such as cultural competency training on health outcomes for minority patients have demonstrated variable findings.18 While many programs are currently evaluating the impact of such efforts on health outcomes, it is also important to understand how such programs are received by practicing clinicians.

We recently conducted a randomized trial to assess the impact of race-stratified performance feedback reports combined with cultural competency training on intermediate outcomes of diabetes care for black patients, including control of glucose, blood pressure and cholesterol.19 We found that these interventions increased the awareness of racial disparities among participating clinicians, but there was no significant change in measures of disease control among their black patients over the ensuing year. The goal of the current study was to conduct a qualitative exploration among primary care clinicians randomized to receive the intervention to better understand their views on racial disparities among their patients and the utility of the intervention.

METHODS

Study Context

This study was conducted at Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates (HVMA), an integrated multispecialty group practice based in eastern Massachusetts. HVMA serves a predominantly insured patient population, with 37 % of diabetic patients self-reporting their race as black. Beginning in the late 1990′s, HVMA implemented an electronic health record and reorganized the structure of the primary care teams to improve chronic disease management.20 This new care model used the electronic health record and a disease registry to track the health of individual patients with diabetes and established a team approach, using nurse practitioners and physician assistants for chronic disease planned visits.

Despite significant gains in the quality of diabetes care and elimination of racial disparities for process measures such as glucose and cholesterol testing, racial disparities in intermediate outcomes of achieving adequate glycemic, blood pressure, and cholesterol control persisted within HVMA.2 These racial differences were found to exist between white and black patients being treated by the same physician even after controlling for differences in socioeconomic status.2, 21

Clinician Intervention

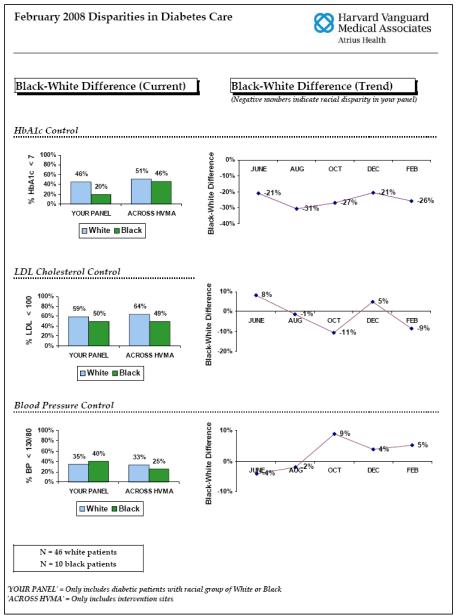

This qualitative study focused on clinicians who had participated in the intervention arm of a randomized trial conducted between May 2007 and June 2008 across 8 health centers. 19 In this trial, 46 primary care physicians and 16 nurse practitioners and physician assistants working together in 31 primary care teams were randomized by primary care team to receive an intervention that included a two-day cultural competency training program followed by monthly race-stratified diabetes performance reports for 12 months (Figure 2).19 All clinicians randomized to the intervention arm of the trial received the performance reports and most [89%] of the primary care teams in the intervention group had at least one clinician participate in the training.

Figure 2.

Example of physician-level clinical performance feedback report

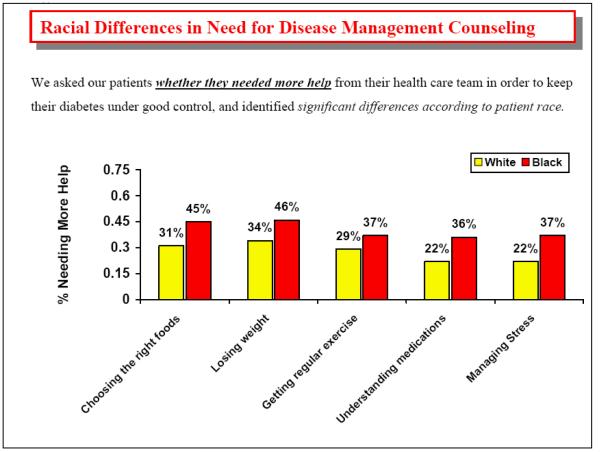

The training was delivered by Harvard Pilgrim Healthcare Foundation, which has delivered many similar programs (www.harvardpilgrim.org/foundation/ilcs). Its aim was to educate clinicians about health disparities and offer skills to improve the delivery of cross-cultural care.22 The training included classroom-based instruction in the causes of disparities, such as a lack of trust in the medical system and potential bias by providers, as well as practical barriers to sources of healthy food and exercise. It also included a half-day visit to a predominantly minority community in Boston to meet with community leaders and patients with diabetes. Clinicians were also informed about ways to collect clinically relevant cultural information and incorporate it into their care plans for patients.19 This training session was followed by monthly distribution of supplementary materials to intervention clinicians based on data collected from surveys and focus groups involving patients with diabetes (Figure 3). These materials provided practical suggestions regarding caring for black patients with diabetes, including the role of diet, religion, and need for self-management support.

Figure 3.

Example of supplementary sheet for clinicians

The clinicians also received clinician-specific monthly performance reports (Figure 2) which contained data on the percentages of a clinician’s white and black patients achieving ideal control of HbA1c, LDL cholesterol and blood pressure, benchmarked to the performance of all other clinicians in the study. The reports also included a cumulative trend in disparities over the 12-month study period. Data on racial disparities were presented without adjusting for other socio-demographic factors.

We previously demonstrated that intervention clinicians were significantly more likely than control group clinicians to acknowledge the existence of racial disparities in their local clinical environment, however there was no significant change in the intermediate outcomes of HbA1c, LDL cholesterol, and blood pressure control for black patients with diabetes.19

Study Subjects

All clinicians randomized to receive the intervention who were still working at HVMA as of March 2009 (n=46) were invited to participate in a semi-structured telephone interview via paper mailings and follow-up e-mail. Participants were offered a $50 gift card in appreciation for their participation. Of those approached, 17 (37%) agreed to be interviewed, including 12 physicians, 4 nurse practitioners, and 1 physician assistant. Interviews were recorded and oral consent was obtained from each participant prior to the interview. The study protocol was approved by the human studies committees of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, and Harvard Medical School.

Data Collection

Interviews were conducted by telephone and recorded using a digital audio recorder. The interviews followed a semi-structured guide developed by the research team and were between 30 and 60 minutes duration, with the same questions posed to all clinicians. The questions focused on three areas: 1) prior beliefs regarding disparities among their own patients, including knowledge of any disparities revealed in performance reports and explanation of their causes; 2) views on the intervention itself, including recall of the performance reports and cultural competency training for those that had attended the training; and 3) behaviors and beliefs about strategies and solutions to reduce disparities. The questions specifically related to those patients with a self-identified race of black rather than other racial or ethnic groups, as this group had been the focus of the original intervention. Interviews were conducted by the lead author, who was blinded to each clinician’s performance report to avoid introducing bias into the interview.

Data Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and entered into the MAXQDA qualitative analysis software program, which facilitates the selection and comparison of coded sections of transcribed scripts (www.maxqda.com). A framework of thematic codes was developed by the research team, who independently coded the first 8 transcripts, using a priori themes from the interview guide and emergent themes from the interviews themselves.23 The subsequent list of coded themes was then reviewed for consistency by two investigators and a final set of codes produced by the whole team. This enhanced set of codes was produced and applied to all interviews independently by two investigators until thematic saturation was reached.24 The resulting framework of themes and sub-themes were then reviewed by the full research team.

RESULTS

Study Cohort

The sample of 17 interviewed clinicians was representative of the larger intervention group (n=62) in terms of training and sex, including 71% who were physicians (vs. 74% of the full intervention group) and 65% who were women (vs. 69% of the intervention group). The average time in clinical practice for clinicians in our interview sample was 23 years compared to 19 years in the larger intervention. There was also a difference with respect to race: all clinicians in the sample identified their race and ethnicity as non-Hispanic white, compared with 82% of the full intervention group. Interviewees were drawn from 6 of the 8 participating health centers.

Understanding of Disparities

Prior awareness of disparities

Clinicians were asked whether they believed racial disparities in diabetes care might be present at the start of the study. There were no obvious differences between the responses of physicians and non-physicians, with 13 of the 17 clinicians (9 physicians, 3 nurse practitioners, and 1 physician assistant) reporting there were some disparities between their black and white patients, particularly in achieving outcomes of optimal HbA1c or blood pressure control, rather than the processes of care delivered by the team, such as regular testing.

Four of the 17 clinicians (3 physicians and one nurse practitioner) did not believe that there were racial disparities among their patients. Rather, variations in their patients’ outcomes were attributed to other factors such as social class or obesity.

I just don’t think there’s that huge a difference… I think it might be a higher percentage of morbidly obese patients that are black, but I certainly have some morbidly obese white patients, too. For the most part, their attitudes about their health seem to me that it’s social class, in my practice, just thinking about my patients, rather than their race. (Physician, male, #10)

Causes of Diabetes Disparities

In response to an open-ended question about the causes of disparities, the interviewees provided a list of causal factors in three main categories: biomedical, socioeconomic and additional racial, ethnic or cultural factors (Table 1). Income-related factors were most commonly cited. Clinicians described how patients struggled to afford drugs, co-pays for office visits, gym membership or healthy food. They also described the indirect effects of low income, such as living in poor housing, poor neighborhoods and experiencing family or job-related stress. These could distract patients from successful control of their diabetes.

Even though their diabetes might be under horrendous control, it wasn’t the top thing on life’s list. you know they might have a kid in jail, or they might have been in the midst of an eviction proceeding or others are at risk of losing their jobs that there were a lot of other topics that were higher on their list than their HbA1c of 13. (Physician, male, #2)

Table 1.

Factors cited by clinicians as causes for disparities in diabetes outcomes among black patients

| Biomedical causes |

| • Higher prevalence of co-morbid conditions (coronary heart disease, hypertension and obesity) among black patients (7)* |

| Socioeconomic causes |

| Income related (12), affecting: |

| • Visit co-pays, drug co-pays, access to phones, internet, transportation, frequent changes of address, ability to afford healthy foods and gym membership |

| Environment (6) affecting: |

| • Poor access to fresh food |

| • Poor access to exercise |

| Work (5) related: |

| • Multiple jobs creating stress and time shortage for self/care office visits |

| • Jobs which prohibit daytime access to office visits |

| Family (3) related: |

| • Multiple caring duties creating stress and time shortages |

| Health literacy (2) levels: |

| • Difficulty in following detailed self care or drug related instructions |

| • Influencing attitudes about health |

| Racial, ethnic or cultural causes |

| Diet (11) |

| • Fatty, fried “southern” food, |

| • High levels of sodium in food |

| • Ethnic/culturally preferred foods |

| Beliefs (9) |

| • Mistrust of medical profession, fear of drugs not working or being bad for black people |

| • Tolerance/preference for larger body sizes, |

| • Faith driven fatalism about disease |

| • Different attitudes regarding need for preventative self care rather than curative treatment |

| Language (6) |

| • Poor communication with clinicians during consultation |

| • Inability to understand standard written advice about diet and exercise |

| Service/Clinical Limitations (2) |

| • Lack of effective outreach to ethnic/racial groups |

| • Lack of culturally appropriate care, education and/or counseling |

Number in parentheses indicates the count of interviews in which the theme was mentioned by providers who acknowledged the presence of racial or ethnic disparities.

Clinicians described patient beliefs and behaviors that they believed were specific to race or cultural group and were detrimental to good control of diabetes. Examples included a religious-based fatalistic attitude towards illness, or a view that “God will mend the disease.” Other clinicians spoke about patients not understanding biomedical concepts of illness prevention, for example the importance of regularly taking a drug even when patients felt well. Clinicians referred to dietary habits which they believed to be specific to their black patients, for example diets with high levels of salt or rich in carbohydrate and fat. Biomedical explanations such as co-morbid conditions or obesity were less frequently mentioned.

Only two clinicians described limitations or shortcomings in the services offered as a potential factor in disparities, such as nutritionist advice that was not culturally relevant. Another clinician thought that the medical group failed to provide appointments at convenient times for those with demanding jobs.

Implementation of the Intervention

Recall of content, frequency and impact of performance reports

Views on receiving the race-stratified performance reports fell into two broad categories. One set of clinicians expressed frustration because they felt unable to act on the information or because they challenged the meaning of the reports (n=11). These clinicians thought that the performance reports did not reflect what was happening in their practices and described them as random, not controlled for socio-economic factors or subject to sampling error. They also thought that even if the results were valid, disparities were not the product of their own actions, leading to frustration.

It’s just not useful information. I see very little that I have accessible at my disposal to make any impact on it, and telling me that it’s there, it changes or doesn’t change, seems to be random and have absolutely nothing to do with what I personally do or can do. (Physician, female, #15)

Responses from other clinicians (n=6) were more positive. These clinicians reported that the data had provoked them to think about why there might be differences between their black and white patients and had motivated them to make a greater effort with their black patients, for example to offer new drugs or nutrition advice.

Well it was an initial kind of negative feeling, you know, like I’m failing in these particular situations. But then there was a feeling of, well these are the things that we’ve really got to focus on so we’re just going to have to pull this apart and try and focus on these things. (Physician, female, #2)

Clinicians were asked about the frequency of the performance reports and whether they remembered receiving the supplementary information sheets containing culturally tailored care recommendations. Of the 17 clinicians, only 4 could remember the monthly frequency (most thought the data had come quarterly) and only 3 could remember having seen the supplementary information. Some interviewees commented that they already received a considerable amount of routine feedback on their clinical activities.

Recall of content and impact of cultural competency training

Ten of the clinicians had attended the cultural competency training but two were unable to supply much detail. Of the 8 clinicians with sufficient recall of the training, a common theme was the educational content about how African-Americans might not trust the health-care system because of historical events, including the Tuskegee syphilis study. Clinicians said they learned that their patients might be afraid of taking medication, worry about being used as a “guinea pig” or that drugs might not work properly for black patients, or generally mistrustful of the motives of health care providers. This might lead patients to “not entirely follow through on our care.” Lack of trust was mentioned as a causal factor for disparities (Table 1) only by those clinicians who had attended the training.

The training also covered the practical problems that might be faced by black patients living in a poor neighborhood. Clinicians recalled learning that grocery stores were not always available locally, and that access to transportation and exercise opportunities was limited. Some clinicians reported surprise at this:

You know I never knew there wasn’t a grocery store [there], I felt so stupid, but now I understand why they eat what they eat. (Nurse Practitioner, female, #4)

Clinicians were questioned about whether they felt the training had any impact on their interactions with patients. There were contrasting views about whether the information about trust had been useful. One clinician reported that it hadn’t come up directly with her patients. Another said that it prompted her to “dig deeper” about whether patients were following medical advice and build trust with patients. Tactics to build trust included asking directly whether patients trusted them, or investing more time communicating in person or by phone. Clinicians also mentioned heightened sensitivity to cultural attitudes related to diet, body shape or access-related barriers as a result of the training.

Strategies and solutions to address disparities

Perceptions about clinicians’ power to affect disparities

Clinicians were asked whether they thought they had the power or ability to affect the causes of disparities. A frequent response was that clinicians were not empowered to act because the underlying structural issues related to low income were beyond their control.

I think that I feel very overwhelmed by this whole kind of concept because in many respects I think that a lot of this is very, very difficult to change because of what happens outside of these four walls. (Physician, female, #8)

Examples include the inability to provide patients directly with healthy food or a place to cook food, to prevent an eviction from taking place or ensuring a job that allows patients time for physician visits. Some clinicians also reported that they could address some of the effects of structural barriers, for example, tackling depression even if the clinician couldn’t directly impact the joblessness that results from the depression.

Current strategies to address disparities

Clinicians were asked to describe their current strategies for managing some of the obstacles to care experienced by their black patients and offered numerous examples of how they approach some of the barriers (Table 2). In relation to co-payment for drugs, this included referring patients to a social worker to explore access to other sources of funds and moving patients onto less expensive generic drugs. In relation to diet and exercise, clinicians talked about offering advice that related to patients’ circumstances, persuading them ‘to walk a bit longer’ or exercise at home if gym membership was unaffordable. Many spoke about using longer visits (up to 40 minutes) to identify strategies appropriate to patients’ circumstances and building positive personal relationships with patients, “just really focusing on them as an individual person”.

Table 2.

Clinicians’ recommended strategies to address disparities in diabetes outcomes

| Barrier | Examples of clinicians’ strategies |

|---|---|

| Drug co-payments | |

| • Switching to cheaper generic drugs | |

| • Applying for “compassionate use” from name brands | |

| • Prescribing combination pills to reduce # of prescriptions | |

| • Referral to social worker for help with drug costs | |

| Visit co-payments | |

| • Managing patients over the phone so they don’t have to come in | |

| • Spreading out physician and nurse practitioner/ physician assistant visits to reduce the cost | |

| Lack of access to good food and exercise | |

| • Initiating a dialogue about existing shopping habits; “trying to be more sensitive to their living situations” | |

| • Supplying suggestions about where to shop | |

| • Initiating a dialogue about access to exercise: “do they have a safe park?” | |

| • Suggesting alternatives to gyms, such as television-based exercise programs | |

| Diet | |

| • Referrals to a nutritionist | |

| • Giving people printed out recipes | |

| • Giving people internet based diet resources | |

| • Understanding realities of a person’s existing diet “What would you like to eat?” rather than saying, “You should have oatmeal with skim milk on it, something you’ve never eaten in your life” | |

Suggestions for new services or programs to tackle disparities

When asked what specific additional resources or programs might help them address disparities, the clinicians offered a range of ideas. Most of these involved extra programs or services rather than new skills for clinicians. A common theme was access to culturally-trained nutritionists. For example, nutritionists who could help patients understand “which of the forms of plantains, green bananas, or other starchy vegetables they’re able to afford are actually going to be better for their diabetes”; or nutritionists that avoid recommending unfamiliar foods such as tofu. Clinicians also mentioned offering nutritional advice in other languages and local educational classes at convenient times:

You can’t be sending someone from here, who works nights, to some centralized kind of a place. (Physician, female, #15)

Clinicians thought that more targeted advice could be delivered by new mechanisms, including home visits to patients by a specialist health educator and group visits for patients. Home visits were described as a way to deliver advice and support that was more appropriate to patients’ home environments. Outreach visits to communities or churches were also suggested to target ethnic groups such as Haitians. Patient group visits to physicians for culturally targeted nutrition or other advice would allow patients to share experiences and offer each other support.

Another theme mentioned by several clinicians was the need to reduce or eliminate co-pays for drugs and office visits, create evening or weekend office hours for those unable to get time off from work during the week and more time with patients.

DISCUSSION

We explored primary care clinicians’ views of racial disparities in diabetes care and their reactions to an intervention designed to reduce these disparities. A minority of clinicians in the sample rejected the idea that race or ethnicity was the driver of any variations in their patients’ outcomes. Those clinicians who did accept the presence of racial and ethnic disparities identified a complex range of causes, including socioeconomic and cultural factors, not all of which they felt empowered to address. Nevertheless, clinicians reported using a number of strategies to address the challenges faced by their black patients. Reactions to the cultural competency training and performance feedback intervention were mixed. Those who had attended the cultural competency training were supportive of this aspect of the intervention. Some clinicians felt the performance reports had been helpful, while others felt powerless to act on the data.

Our intervention was aimed at improving outcomes by changing the beliefs and behavior of physicians to improve the quality of care, rather than acting directly on patient or community factors (Figure 1). Our intervention demonstrated a significant increase in the awareness of racial disparities in diabetes care among participating clinicians, but ultimately had no significant effect on clinical outcomes within one year.19 In conducting these qualitative interviews we sought to explore some possible explanations for these findings, although such explanations must remain tentative as it was not possible to link individual clinicians’ interviews with their record of performance in reducing disparities among their own patients.

One possible explanation may relate to the strength of the intervention itself, as we found that few of the clinicians could remember the supplementary information sheets, which offered suggestions for improving their approaches to caring for black patients with diabetes. Other clinicians noted that they already received extensive feedback of clinical performance data, and so our intervention may have gone unnoticed. Our findings may parallel prior studies that have identified contextual practice-related factors, such as lack of time and lack of awareness, as barriers to clinicians’ adoption of evidence based guidelines in their practice.25

Lack of awareness, however, is unlikely to be a sufficient explanation for why the intervention failed to have an impact on clinical outcomes, as our main study found that the clinicians exposed to the intervention were significantly more likely to acknowledge the presence of racial disparities among their patients compared to clinicians in the control group.19 Another possible explanation could relate to the physicians’ observation that the strongest causal factors for their patients’ diabetes outcomes were socioeconomic and other patient-level factors that were beyond their control. This finding suggests that future interventions to reduce disparities should target the upstream determinants of individuals’ health, such as poor quality housing or low incomes, rather than the behavior of clinicians.26

However, this conclusion leaves unresolved the question of what role there is for healthcare providers to take action to reduce disparities. Patient-level factors certainly interact with the actions of healthcare providers, and our clinician interviews revealed that some patient-level barriers were considered to be modifiable. The clinicians were able to offer a range of suggestions that would require the healthcare organization to invest in new services or improve access to existing services. For example, several of our interviewees suggested community interventions, such as outreach visits to patients’ neighborhoods and homes.

Our study suggests that educating clinicians to change their behavior may not be sufficient to improve minority patient outcomes. A recent review of interventions to reduce disparities found that multi-factorial and culturally tailored interventions have been shown to be effective in reducing disparities in outcomes in diabetes as well as other clinical areas.10 Thus, more restricted interventions such as the ones in our study may have only a limited impact on health disparities.

Does this mean that the scope for interventions aimed at changing individual clinician behavior within organizations is also limited? Prior research has highlighted the presence of unconscious bias or stereotyping by clinicians which may influence decisions about treatment recommendations.27,28 Training programs have been recommended to increase clinicians’ awareness of disparities and their historical roots, employing a range of cognitive psychological techniques, including enhanced empathy, partnership and relationship building skills.28 We found that the training about the history of disparities did have some impact on clinicians’ awareness of disparities. All the clinicians who discussed mistrust expressed by African American patients had attended the training session, whereas this theme was absent from the interviews of those clinicians who had not attended this training.

Other research has suggested that disparities may result from clinical uncertainty, driven by difficulties in communication between clinicians and minority patients.13 In the context of our study, this observation would suggest that a clinician-focused intervention needs to improve clinicians’ ability to collect information from minority patients to achieve more appropriate care. We did find examples of clinicians referring to poor knowledge of patients’ home and neighborhood environments, or potential mistrust. We also saw that that the intervention, particularly the regular performance feedback, had spurred some clinicians to make greater efforts to win patients’ trust and better understand their environments. However, it was not possible within the scope of this research to explore the efficacy of improved knowledge on clinicians’ performance.

Overall, our findings suggest that it may be valuable for healthcare organizations to understand their own clinicians’ perceptions about the causes and solutions to disparities as they design interventions to reduce disparities. In our qualitative study, clinicians provided potentially useful insights into the barriers faced by patients, and they suggested solutions that could have an impact on reducing some barriers identified by both patients and clinicians.

However, our findings also present an important challenge to interventions based on changing clinicians’ knowledge and attitudes regarding disparities. We found that some clinicians rejected the concept that race or ethnicity was at the root of any differences in health outcomes, despite a program of training and performance feedback. Even if cultural competency training and performance reports were implemented more robustly or delivered more frequently, these actions would be unlikely to persuade all clinicians of the causal role of race and ethnicity. In our study, some clinicians believed that socioeconomic factors explained racial differences in diabetes outcomes, and argued that the performance reports should have controlled for these mediating factors. This belief reflects a wider debate in the literature about how to define and measure disparities with regard to potential mediators such as income or education,29,30 posing a challenge to clinician-focused interventions which are built on acceptance of racial disparities.

Our study findings should be interpreted in the context of potential limitations. We assessed perceptions of disparities only among clinicians exposed to the intervention, and so we cannot draw conclusions related to these perceptions among clinicians in the control arm of the intervention. We interviewed clinicians approximately 9 to 12 months after the intervention finished and nearly two years after the cultural competency training. However, most interviewees displayed reasonable recall of the intervention components. In addition, all of our interviewees were white, limiting our ability to draw conclusions regarding race-concordant clinical interactions. We also only interviewed 37% of the original intervention group, and the beliefs of non-responders may have differed from those we interviewed. However, our sample was representative of the entire intervention group in terms of training and gender, and the interviews did contain a range of views, both positive and negative, about the intervention. Nevertheless, given the subject matter and the risk of bias from interviewees wishing to give socially desirable responses, more negative views might be under-represented and therefore pose a greater challenge for interventions of this kind.

In conclusion, we found that while cultural competency training was fairly well received by these primary care clinicians, the increased knowledge from this training coupled with performance feedback was difficult to translate into action due to a variety of barriers. As highlighted by clinicians in this study, future interventions to address disparities will likely need to couple individual clinician-focused programs with broader multi-level efforts directed at patients and communities to improve the outcomes of minority patients with diabetes.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Commonwealth Fund Harkness Fellowship in Health Care Policy and Practice, a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Health Disparities Research Program of Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (NIH Award #1 UL1 RR 025758 and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health centers). We thank the clinicians at Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates for participating in this study.

Footnotes

All authors confirm that they have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Trivedi AN, Zaslavsky AM, Schneider EC, Ayanian JZ. Trends in the quality of care and racial disparities in Medicare managed care. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(7):692–700. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa051207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sequist TD, Adams A, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, Ayanian JZ. Effect of quality improvement on racial disparities in diabetes care. Arch Intern Med. 2006;66(6):675–681. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.6.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Differences in control of cardiovascular disease and diabetes by race, ethnicity, and education: U.S. trends from 1999 to 2006 and effects of medicare coverage. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(8):505–515. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-8-200904210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones RG, Trivedi AN, Ayanian JZ. Factors influencing the effectiveness of interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(3):337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peek ME, Cargill A, Huang ES. Diabetes health disparities: a systematic review of health care interventions. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(Suppl 5):101–156. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beach M, Gary T, Price E, Robinson K, Gozu A, Palacio A, et al. Improving health care quality for racial/ethnic minorities: a systematic review of the best evidence regarding provider and organization interventions. BMC Public Health. 2006;6(1):104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, Institute of M, Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health C . Unequal Treatment : Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C.: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King R, Green A, McGrory A, Donahue E, Kimbrough-Sugick V, Betancourt J. A plan for action: key perspectives from the racial/ethnic disparities strategy forum. Milbank Quarterly. 2008;86(2):241–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Washington DL, Bowles J, Saha S, Horowitz CR, Moody-Ayers S, Brown AF, et al. Transforming clinical practice to eliminate racial-ethnic disparities in healthcare. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):685–691. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0481-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chin MH, Walters AE, Cook SC, Huang ES. Interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(Suppl 5):7S–28S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayanian JZ. Determinants of racial and ethnic disparities in surgical care. World J Surg. 2008;32(4):509–515. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9344-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clancy C. Improving care quality and reducing disparities: physicians’ roles. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(11):1135–1136. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balsa A, McGuire M. Prejudice, clinical uncertainty and stereotyping as sources of health disparities. Journal of Health Economics. 2003;(22):89–116. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(02)00098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, Ngo LH, Raymond KL, Iezzoni LI, et al. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1231–1238. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0258-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, Kerner JF, Sistrunk S, Gersh BJ, et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(8):618–626. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902253400806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sequist TD, Ayanian JZ, Marshall R, Fitzmaurice GM, Safran DG. Primary-care clinician perceptions of racial disparities in diabetes care. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):678–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0510-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sehgal AR. Impact of quality improvement efforts on race and sex disparities in hemodialysis. JAMA. 2003;289:996–1000. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.8.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, Robinson KA, Gozu A, Palacio AM, et al. Cultural competence: a systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Med Care. 2005;43:356–373. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156861.58905.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sequist TD, Fitzmaurice GM, Marshall R, Shaykevich S, Marston A, Safran DG, et al. Cultural competency training and performance reports to improve diabetes care for black patients: a cluster randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(1):40–46. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-1-201001050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimura J, DaSilva K, Marshall R. Population management, systems-based practice, and planned chronic illness care: integrating disease management competencies into primary care to improve composite diabetes quality measures. Dis Manag. 2008;11(1):13–22. doi: 10.1089/dis.2008.111718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sequist TD, Fitzmaurice GM, Marshall R, Shaykevich S, Safran DG, Ayanian JZ. Physician performance and racial disparities in diabetes mellitus care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(11):1145–1151. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith WR, Betancourt JR, Wynia MK, Bussey-Jones J, Stone VE, Phillips CO, et al. Recommendations for teaching about racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(9):654–665. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-9-200711060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess R, editors. Analyzing Qualitative Data. Routledge; London: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denzin N, Lincoln Y. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage; Newbury Park: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams DR, Costa MV, Odunlami AO, Mohammed SA. Moving upstream: how interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;(Suppl 14):S8–S17. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000338382.36695.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.vanRyn M, Fu SS. Paved with good intentions: do public health and human service providers contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):248–255. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dovidio JF, Penner LA, Albrecht TL, Norton WE, Gaertner SL, Shelton JN. Disparities and distrust: The implications of psychological processes for understanding racial disparities in health and health care. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(3):478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LeCook B, McGuire TG, Zuvekas SH. Measuring trends in racial/ ethnic health care disparities. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(1):23–48. doi: 10.1177/1077558708323607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawachi I, Daniels N, Robinson DE. Health disparities by race and class: why both matter. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(2):343–352. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]