Abstract

SUMMARY

In its early history, life appeared to depend on pyrophosphate rather than ATP as the source of energy. Ancient membrane pyrophosphatases that couple pyrophosphate hydrolysis to active H+ transport across biological membranes (H+-pyrophosphatases) have long been known in prokaryotes, plants, and protists. Recent studies have identified two evolutionarily related and widespread prokaryotic relics that can pump Na+ (Na+-pyrophosphatase) or both Na+ and H+ (Na+,H+-pyrophosphatase). Both these transporters require Na+ for pyrophosphate hydrolysis and are further activated by K+. The determination of the three-dimensional structures of H+- and Na+-pyrophosphatases has been another recent breakthrough in the studies of these cation pumps. Structural and functional studies have highlighted the major determinants of the cation specificities of membrane pyrophosphatases and their potential use in constructing transgenic stress-resistant organisms.

INTRODUCTION

Pyrophosphate (PPi) can form spontaneously under the geochemical conditions that prevailed in the early history of life and therefore may have served as the main energy currency in the early forms of life—the so-called “PPi world” as opposed to the “ATP world” (Fig. 1) (1, 2). Relics of ancient PPi-based metabolic pathways are found in bacteria, archaea, protists, and plants as enzymatic and membrane transport reactions that utilize PPi instead of ATP. These reactions employ PPi energy to produce useful work, as opposed to the heat production associated with PPi hydrolysis by ubiquitous soluble pyrophosphatases (PPases).

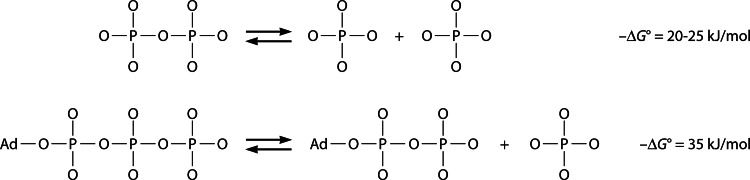

Fig 1.

Hydrolyses of PPi to Pi and of ATP to ADP and Pi yield appreciable energy that can be used to drive coupled chemical or transport reactions. Ad, adenosine moiety.

In contemporary organisms, PPi is formed as a by-product of nearly 200 biosynthetic reactions in which nucleoside triphosphates are converted to nucleoside monophosphates and PPi (3). In many cases, PPi inhibits the PPi-generating reactions; therefore, its free cellular concentration must be under strict control. This is achieved by the hydrolysis of PPi to phosphate via the action of PPase. The total concentration of PPi in prokaryotes is typically in the millimolar range, but the majority of PPi is stored, together with other polyphosphates and metal cations, in a condensed form in volutin granules (4). PPi thus plays an important role in cellular regulation and energy storage. A comprehensive description of all aspects of PPi metabolism and its roles in different organisms can be found in a monograph by Heinonen (3).

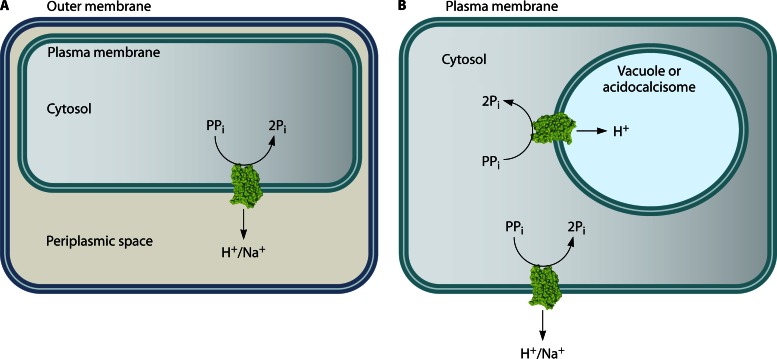

Membrane PPase, discovered in bacteria nearly 50 years ago (5, 6), is an integral membrane protein that couples the hydrolysis of PPi to the transport of monovalent cations against an electrochemical potential gradient (Fig. 2). This enzyme is equally common in prokaryotic domains, and its gene is present in a quarter of fully sequenced bacterial and archaeal genomes. Among eukaryotes, all plants and many protists contain genes encoding H+-translocating PPase (H+-PPase), whereas animals and fungi do not. Two homologous families of membrane PPases are known, K+ independent and K+ dependent (10–13); members of the latter family are activated severalfold in the presence of millimolar concentrations of K+. Both families of membrane PPase had long been thought to transport only H+. Only recently has it become known that in prokaryotes, the K+-dependent family is dominated by PPases that transport Na+ (Na+-PPases) (10, 11) or both Na+ and H+ (Na+,H+-PPases) (12) and accordingly require Na+ for PPi hydrolysis. The determination of the three-dimensional (3D) structures of a plant H+-PPase (14) and a bacterial Na+-PPase (15) has been another recent breakthrough in studies of membrane PPases. Remarkably, membrane PPase is formed by a single polypeptide of ∼75 kDa that does not share structural similarity to soluble PPases or ubiquitous ATP-powered pumps. This simple enzyme can be produced in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli, which lack membrane PPases, and characterized in inverted membrane vesicles (IMVs) (16, 17). The active site of the enzyme, which faces the cytoplasm in intact organisms, lies on the outside surface of IMVs.

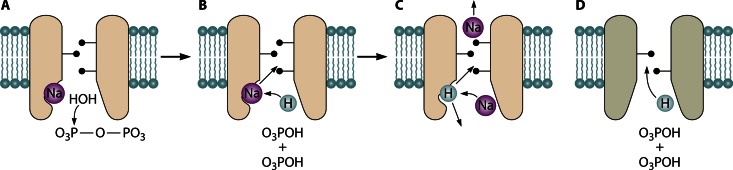

Fig 2.

Orientation of membrane PPase and ion fluxes in prokaryotic (A) and eukaryotic (B) cells. Acidocalcisomes are acidic phosphorus and cation storage organelles that were originally identified in protists (7) and resemble plant vacuoles. Acidocalcisomes with membrane-bound PPases are also present in some bacteria (8, 9). To date, only H+-translocating PPases have been identified in acidocalcisomes and vacuoles. In both cases, the PPase active site faces the cytosol, and cations are transported out of it. H+-PPases localized to the plasma membrane and Golgi apparatus have also been reported for plant cells.

This overview addresses the evolution of transport and cofactor specificities and their structural basis in membrane PPases, with an emphasis on Na+-transporting PPase subfamilies. H+-PPase was the subject of several previous reviews (18–22); therefore, the section on this enzyme presents only major new findings. We also consider the role of membrane PPases and their exploitation to construct stress-resistant transgenic organisms.

H+-PPase

Herrick and Margareta Baltscheffsky first reported energy-linked PPi synthesis and hydrolysis activities in the photosynthetic alphaproteobacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum (5, 6). Further studies indicated that R. rubrum PPase functions as an H+ pump (23). This and most other prokaryotic H+-PPases belong to the K+-independent family. K+-dependent H+-PPases are relatively rare in prokaryotes (11) but are abundant in plants (19, 20) and protists (24, 25).

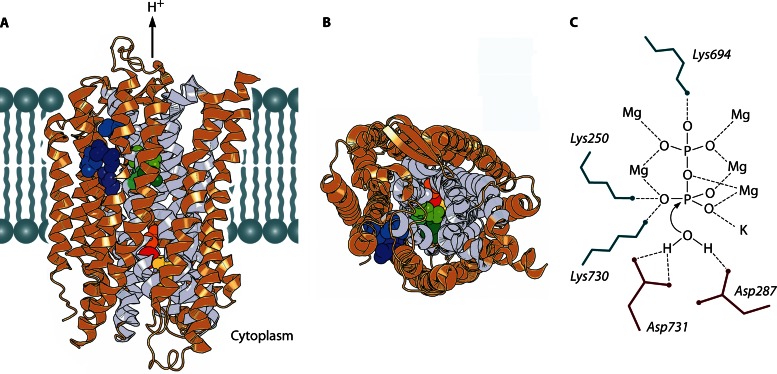

Attempts to grow crystals of prokaryotic H+-PPase that diffract to an atomic resolution have not yet been successful (26). However, the structure of a K+-dependent plant vacuolar H+-PPase (from Vigna radiata) complexed with Mg2+, K+, and imidodiphosphate (a close PPi analogue having NH instead of O in the bridge position) was recently determined at a resolution of 2.35 Å (14). This enzyme forms a tight homodimer in the crystal in which each subunit consists of two concentric rings formed by 6 and 10 α-helical segments, respectively (Fig. 3A and B). The central part of the subunit is hydrophilic and forms, on its cytoplasmic side, the PPi-binding site, which continues to the vacuolar side as an H+ conductance channel. PPi is bound via ionic interactions of all its oxygens with five protein-bound Mg2+ ions, one K+ ion, and three protein Lys residues (Fig. 3C). The determination of this structure allowed the identification of the nucleophilic water molecule located at the entrance to the H+ conductance channel.

Fig 3.

Structure of V. radiata H+-PPase (Protein Data Bank [PDB] accession number 4A01) (11) and presumed coordination of the substrate. (A and B) Two views of the PPase subunit (in the plane of and perpendicular to the membrane) showing bound imidodiphosphate (yellow), K+ ion (red), residues occupying the position that determines K+ dependence (A537) (orange), alternative positions of the gate-forming residue (E301/G297/S235) (shades of green), and positions specific for Na+,H+-PPase (L148/T152/V204/I227) (shades of blue). Imidodiphosphate, K+, and the indicated residues are shown as spheres; the remainder of the molecule is presented as a ribbon diagram. The inner-circle helices are shown in gray, and the rest of the molecule is shown in light brown. The right side of the subunit in panels A and B forms a contact with the second subunit. (C) Presumed coordination of PPi and the water nucleophile in the active site. Ionic interactions and hydrogen bonds are depicted as dashed lines. Six of the nine PPi ligands are protein-bound metal ions (Mg2+ and K+). PPi hydrolysis proceeds via direct attack of the water molecule without formation of a phosphorylated intermediate. Panels A and B were created with PyMOL (PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.5.0.4; Schrödinger, LLC).

Importantly, the V. radiata PPase structure is remarkably similar to that of Thermotoga maritima Na+-PPase (15) and may thus be common to all prokaryotic membrane PPases that share the same membrane topology (27). In accord with this prediction, all 10 polar active-site residues that form contacts with PPi (Lys residues 250, 694, and 730), 5 Mg2+ ions (Asp residues 253, 257, 283, 507, 691, and 727 and Asn534), and a K+ ion (Asn534) (14) are conserved in prokaryotic PPases. The ion conductance channel also appears to be highly conserved: of the six polar residues present, three are invariably Asp (at positions 287, 294, and 731), and rare replacements of Arg242 and Lys742 are not correlated with changes in transported cation specificity; only substitutions for Glu301 may be associated with a change in specificity (see below). Most of the 60 residues conserved throughout the membrane PPase superfamily belong to the inner ring helices that have been shown to form the PPi-binding site and H+ conductance channel in V. radiata and T. maritima PPases (14, 15), and extensive mutagenesis studies of Streptomyces coelicolor H+-PPase suggested that these residues are important (28, 29).

Na+-PPase

The consensus view that all homologues of R. rubrum PPase found in different organisms are H+ pumps was held for 4 decades until one archaeal PPase (from Methanosarcina mazei) and two bacterial PPases (from Moorella thermoacetica and T. maritima) were demonstrated to mediate PPi-dependent transport of Na+ rather than H+ into IMVs when expressed in E. coli cells (10). This study was prompted by the observation that T. maritima PPase, unlike all other examined membrane PPases, absolutely required Na+ for hydrolytic activity (30). However, this thermophilic enzyme has low activity at temperatures compatible with membrane integrity of E. coli. Results obtained with mesophilic M. mazei PPase demonstrated that Na+ transport was (i) accompanied by the generation of a membrane potential (as determined by oxonol VI fluorescence), (ii) unaffected by the protonophore carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), (iii) inhibited by the Na+ ionophore monensin, and (iv) stimulated by the K+ ionophore valinomycin (10), thus defining this enzyme as an electrogenic Na+ pump. Later studies (11, 31) indicated that, rather than being a curious oddity, Na+-transporting PPases (Na+-PPases) prevail in the K+-dependent family of membrane PPases.

Kinetic measurements performed with uncoupled E. coli IMVs indicated that binding of one or two Na+ ions confers hydrolytic activity to Na+-PPases (11, 30, 32). Li+ can substitute for Na+ as an activator of T. maritima Na+-PPase (30).

The main effect of K+ is to markedly increase the affinity of Na+-PPase for Na+ (10, 30, 32). Accordingly, Na+ or Li+ concentrations tens of times lower are sufficient to attain a comparable level of PPi-hydrolyzing activity in the presence of 50 mM K+. Additionally, K+ increases the catalytic constant for PPi hydrolysis by 1.6- to 4-fold. Only one binding site for K+ was detected by X-ray crystallography (15) and activity measurements in Na+-PPases. Addition of Na+ alone was found to be sufficient to confer hydrolytic and transport activity to Na+-PPase, yet the activity was lower than that in the presence of both Na+ and K+ (10, 30, 32). These observations suggested that Na+ can functionally replace K+ in the enzyme's K+-binding site. Importantly, the M. mazei PPase was shown to be unable to transport Rb+, which can substitute for K+ as a PPase activator, into or out of IMVs concurrent with the inward transport of Na+ (10). This finding suggested that the function of K+ (and Rb+) is limited to an activating role, as seen in K+-dependent plant H+-PPases (33, 34).

As noted above, the 3D structures of T. maritima Na+-PPase (15) and V. radiata H+-PPase (14) are very similar. One significant difference, however, is that the gate-forming Asp-Lys dyad is replaced by an Asp-Lys-Glu triad in the T. maritima enzyme.

Na+,H+-PPase

Members of the most recently discovered bacterial subfamily of Na+,H+-PPases resemble Na+-PPases in terms of their cation requirements: they absolutely need Na+ for activity and are additionally activated by K+, but unlike the latter, they mediate transport of both Na+ and H+ in E. coli IMVs. The best-characterized Na+,H+-PPase is that of Bacteroides vulgatus (12). Both transport activities of this protein are inhibited by aminomethylenediphosphonate, a nonhydrolyzable PPi analogue that interacts specifically with membrane PPases (35). Na+ accumulation is inhibited by the Na+ ionophore ETH157, whereas the H+ ionophore CCCP is slightly stimulatory. These ionophores have the opposite effect on H+ transport: no effect of ETH157 and severe inhibition by CCCP. Valinomycin stimulates both transport activities in the presence of K+. Collectively, data obtained by using ionophores indicate that the transport processes are electrogenic and exclude the possibility that either the Na+ or H+ gradient formed by Na+,H+-PPases is generated by secondary antiport effects, for instance, by a Na+/H+ antiporter.

A unique feature of Na+,H+-PPase that distinguishes it from other transporters of Na+ and H+ is that it maintains H+ and Na+ transport activities over wide ranges of H+ and Na+ concentrations, with little or no competition between the transported ions under physiological conditions (12). An intriguing possibility is that Na+,H+-PPases transport both ions in each catalytic cycle. Given that PPi hydrolysis in vivo liberates 20 to 25 kJ/mol of energy (3), transport of two monovalent ions per PPi molecule is thermodynamically permitted in membranes that generate low or moderate electrochemical potential gradients, like those in fermentative bacteria (36). Alternatively, the transport of H+ and Na+ may occur in different subunits of dimeric PPase and therefore require one PPi molecule per cation. However, this mechanism would imply a preexisting or induced structural asymmetry in the enzyme dimer that is not evident in the crystal structures of the monospecific H+- and Na+-PPases (14, 15).

It should be noted that transport promiscuity is not uncommon in the parallel ATPase world. Thus, Na+,K+-ATPase (37) and Na+-coupled rotary ATP synthases (38–40) can transport H+ instead of Na+ but only at a low pH and/or Na+ concentration. Methanosarcina acetivorans A1Ao ATP synthase appears to be the only other transporter capable of generating both Na+ and H+ gradients of the same direction under physiological conditions (41). However, the Na+ and H+ transport activities of this unique ATPase are not tightly coupled, allowing H+ transport and ATP hydrolysis to proceed in the absence of Na+ at pH 5. Na+,H+-PPase retains its Na+ transport activity and the Na+ dependence of its hydrolytic activity in acidic medium (12).

MECHANISM OF TRANSPORT

A detailed description of the transport phenomena in PPase pumps would require knowledge of (i) the mechanism of PPi hydrolysis, (ii) the mechanism of cation transport through the protein, (iii) the means by which these two processes are coupled, and (iv) the way in which cation selectivity is achieved. Of these four aspects, the mechanism of hydrolysis, at least its initial step, is the most explored. Based on the structure of the complex of V. radiata H+-PPase with imidodiphosphate, K+, and five Mg2+ ions (14), it can be inferred that the key elements of the reaction (Fig. 3C) are similar to those identified in soluble PPases (42, 43). In both cases, hydrolysis results from a direct attack of an activated water molecule on PPi bound to the enzyme via multiple Mg2+ ions and a few basic groups. However, the mode of activation of the nucleophilic water seems to be different. A single water molecule occupying a position suitable for the attack on PPi is bound to two Asp residues in V. radiata H+-PPase (Fig. 3C), whereas it interacts with three Mg2+ ions (42), or two Mg2+ ions and an Asp carboxylate (43), in soluble PPases.

In addition to explaining the much lower hydrolytic activity of membrane PPases, this difference may be of fundamental importance for their transport activity. Coordination to two or three Mg2+ ions converts water into highly nucleophilic hydroxide before it hydrolyzes PPi (42, 44), whereas two Asp residues bind an unmodified water molecule. In the latter case, the attacking water leaves an Asp-bound proton near the entrance to the ion conductance channel (Fig. 4A and B). In H+-PPases, this proton can directly enter the ion conductance channel (14) (Fig. 4D), whereas in Na+-PPases, it may trigger Na+ transport by displacing Na+ from its initial binding site and subsequently be released into the cytosol under the action of an incoming Na+ ion (Fig. 4C). In the framework of this “billiards-type” mechanism, a possible route to Na+,H+-PPase would require only gate tuning to allow H+ entrance into the channel along with Na+. Thus, H+-PPases may independently have emerged as a result of mutations that disallowed Na+ binding and tuned the gate for H+ passage (Fig. 4D).

Fig 4.

Possible elements of the coupling mechanisms in membrane PPases. (A to C) Three key events in the “billiards-type” mechanism of Na+-transporting PPases: Na+, PPi, and nucleophilic water binding (A); PPi hydrolysis and displacement of Na+ from its binding site into the ion conductance channel by the H+ ion generated from the nucleophilic water (B); and subsequent displacement of the bound H+ ion by incoming Na+ (C). Depending on whether the H+ ion is released into the medium or the ion conductance channel, the transporter is classified as Na+-PPase or Na+,H+-PPase, respectively. (D) Direct entrance of the H+ ion generated during PPi hydrolysis into the ion conductance channel in H+-PPases, which lack the transitional binding site for Na+ and H+.

Lin et al. (14) suggested that H+ translocation in V. radiata H+-PPase occurs by a Grotthuss mechanism, as in bacteriorhodopsin and P-type H+-ATPase (45), wherein proton transportation results from a series of H—O bond breakage and formation events in adjoining water molecules, without physical movement of the proton. Keeping in mind the structural similarity of the cation conductance channels in H+-PPase and Na+-PPase and that the Grotthuss mechanism is not operational in Na+ transport, Kellosalo et al. proposed a mechanism involving physical transportation of both cations between transitory binding sites (15). The discovery of Na+,H+-PPases that transport both cations lent further credence to the latter mechanism. Given that Na+ is coordinated to six water molecules and H+ is hydrogen bonded to four or two water molecules (46, 47), the wide water-filled ion conductance channel found in PPase (14, 15) provides a good environment for transportation of hydrated cations between charged acidic groups without (or with only partial) exchange of bound water.

Coupling of transport to hydrolysis is perhaps the least understood aspect of PPi-energized transport. By analogy with ion-transporting ATPases, Kellosalo et al. (15) proposed a binding change mechanism for membrane PPases wherein PPi binding induces a conformational change that closes the active site, transiently opens the ion transport channel, and allows passage of the transported ion. However, membrane PPase is basically different from ATPases in that its hydrolysis site, where a proton is generated upon water attack on PPi, is quite close to the ion conductance channel (14). PPase may thus exploit Mitchell's “direct-coupling” mechanism, which implied that the transported proton is the one derived from the chemical reaction (48). The mechanism proved untrue and was replaced by Boyer's binding change mechanism (49) in the case of H+-ATPase, in which the hydrolysis site and ion conductance channel are well separated in space. Whereas protein conformation certainly undergoes changes (such as movement of transmembrane helix 12 [15]) during ion translocation by membrane PPase, the major driving force for gate opening may be an increased local concentration of H+ ions, as illustrated in Fig. 4. That gate opening is intimately linked to the hydrolysis step is consistent with the gate being closed in all available structures of membrane PPases, including those with bound substrate analogue and the product phosphate (14, 15).

EVOLUTION AND SIGNATURE RESIDUES OF MEMBRANE PPases

Membrane PPase genes are found in the majority of bacterial and archaeal phyla (Table 1). The distribution of PPase is not only broad but also sporadic, as deduced from an analysis of complete genomes. For example, the firmicutes Clostridium tetani and Clostridium thermocellum have genes for Na+-PPase and H+-PPase, respectively, whereas the closely related organisms Clostridium perfringens and Clostridium acetobutylicum do not. Thus, membrane PPase genes have a high propensity for lineage-specific loss and/or lateral transfer. Na+-PPases and H+-PPases appear to be equally widespread among bacteria (Table 1), but the total number of identified H+-PPase sequences is about twice as high. Most prokaryotic H+-PPases belong to the K+-independent enzyme family. Na+,H+-PPase is most common in Bacteroidetes, Planctomycetes, and Spirochaetes but is rarely found in other bacterial phyla. In Archaea, H+-PPase predominates, Na+-PPase is restricted to Euryarchaeota, and Na+,H+-PPase is never observed. Although only one type of membrane PPase is usually present in a given organism, the genomes of some prokaryotes, for example, those of the bacterium M. thermoacetica and methanogenic archaea from the Methanosarcina order, contain genes encoding H+-PPase and Na+-PPase as separate proteins.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of H+-, Na+-, and Na+,H+-PPases in prokaryotesa

| Phylumb | No. of sequenced genomes | No. of H+-PPases | No. of Na+-PPases | No. of Na+,H+-PPases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||||

| Acidobacteria | 8 | (5) | ||

| Actinobacteria | 234 | (73) | 2 | |

| Alphaproteobacteria | 224 | (111) | 1 | |

| Bacteroidetes | 89 | 35 (2) | 6 | 15 |

| Betaproteobacteria | 135 | (35) | ||

| Chlamydiae | 52 | (2) | 1 | |

| Chrysiogenetes | 1 | (1) | ||

| Cyanobacteria | 71 | |||

| Deinococcus-Thermus | 19 | |||

| Deltaproteobacteria | 54 | (28) | 11 | |

| Elusimicrobia | 2 | (2) | ||

| Epsilonproteobacteria | 81 | |||

| Fibrobacteres | 2 | |||

| Firmicutes | 465 | 16 (31) | 36 | 4 |

| Fusobacteria | 5 | 2 | ||

| Gammaproteobacteria | 465 | (24) | 11 | |

| Gemmatimonadetes | 1 | (1) | ||

| Green nonsulfur bacteria | 16 | (13) | 7 | |

| Green sulfur bacteria | 13 | (6) | 8 | 1 |

| Hyperthermophilic bacteria | 39 | 3 (4) | 24 | |

| Other proteobacteria | 1 | (1) | ||

| Planctomycetes | 7 | (1) | 2 | 2 |

| Spirochaetes | 53 | 7 (3) | 5 | 8 |

| Synergistetes | 4 | 4 | ||

| Tenericutes | 65 | |||

| Verrucomicrobia | 4 | (2) | 1 | |

| Unclassified | 1 | (1) | ||

| Archaea | ||||

| Crenarchaeota | 44 | (15) | ||

| Euryarchaeota | 93 | (16) | 9 | |

| Korarchaeota | 1 | (1) | ||

| Nanoarchaeota | 1 | |||

| Thaumarchaeota | 5 | (5) |

Membrane PPase sequences were detected as hits in a BLAST search of complete prokaryotic genomes available in KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) as of January 2013, using R. rubrum H+-PPase as the query. Each sequence was classified as H+-, Na+-, or Na+,H+-PPase and according to K+ dependence based on experimental evidence or signature residues. The numbers of protein sequences shown without parentheses and those in parentheses refer to K+-dependent and K+-independent PPases, respectively.

The taxonomic terminology is that of KEGG.

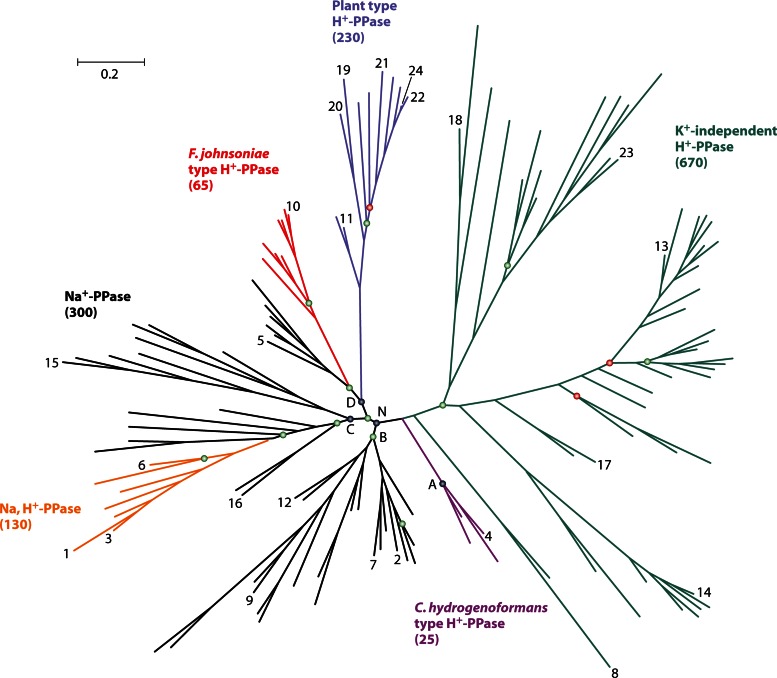

The evolutionary tree of membrane PPases (Fig. 5), including plant and protist H+-PPases, consists of independently evolving K+-dependent and K+-independent families (13). The key residue responsible for the loss of K+ dependence was identified by sequence comparison. Thus, the residue corresponding to positions 460 in Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans PPase and 537 in V. radiata PPase is invariably Ala in K+-dependent enzymes and Lys in K+-independent enzymes (13). Furthermore, introduction of Lys in place of Ala at the A/K site of the C. hydrogenoformans H+-PPase (13) abolishes K+ dependence but not hydrolytic or transport activities. These findings suggest that the NH3+ group of Lys occupies the space otherwise used by K+, a suggestion that is consistent with the structures of K+-bound V. radiata and T. maritima PPases (14, 15). The role of K+, and presumably the Lys NH3+ group, is to facilitate the attack of a water molecule on the substrate by coordinating its electrophilic phosphate residue (Fig. 3C). The mechanism by which K+ dramatically enhances Na+ binding to Na+-PPase and Na+,H+-PPase (10–12, 30) is still unknown.

Fig 5.

Simplified phylogenetic tree of verified and putative membrane PPases. The sequences in the tree were selected by redundancy filtering to leave only representative sequences for each group of highly similar sequences. The total number of sequences found in the NCBI protein sequence database for each PPase subfamily is given in parentheses. The tree consists of one K+-independent and five K+-dependent subfamilies, shown in different colors. K+-independent H+-PPases occur in bacteria, archaea, plants, and protists; C. hydrogenoformans-type H+-PPases, F. johnsoniae-type H+-PPases, and Na+,H+-PPases occur in bacteria only; plant-type H+-PPases occur in plants, protists, and bacteria (Leptospira); and Na+-PPases occur in bacteria and archaea (a few protists and algae may also have Na+-PPase genes). The letters A, B, C, D, and N indicate the nodes of different clades within the K+-dependent family. The nodes with MrBayes clade credibility values in the ranges of 70 to 84 and 50 to 69 are marked with green and red circles, respectively; for all other nodes, the credibility values were 85 to 100. The scale bar represents 0.2 substitutions per residue. The PPases with experimentally verified cation specificity are indicated as follows: 1, Akkermansia muciniphila; 2, Anaerostipes caccae; 3, B. vulgatus; 4, C. hydrogenoformans; 5, Chlorobium limicola; 6, Clostridium leptum; 7, C. tetani; 8, C. thermocellum; 9, Desulfuromonas acetoxidans; 10, F. johnsoniae; 11, Leptospira biflexa; 12, M. thermoacetica; 13, R. rubrum; 14, S. coelicolor; and 15, T. maritima (bacteria); 16, M. mazei (Na+-PPase); 17, M. mazei (H+-PPase); and 18, Pyrobaculum aerophilum (archaea); 19, Plasmodium falciparum; 20, Toxoplasma gondii; and 21, Trypanosoma cruzi (protists); 22, Arabidopsis thaliana (AVP1); 23, Arabidopsis thaliana (AVP2); and 24, V. radiata (plants).

All members of the K+-independent family appear to operate as H+ pumps. The K+-dependent family is more diverse and can be phylogenetically classified into four major clades rooting at nodes A, B, C, and D (11, 12). Clades A and B are populated by H+- and Na+-PPases, respectively; clade C contains both Na+- and Na+,H+-PPases; and clade D members possess both Na+- and H+-PPases. Na+-PPases thus dominate the K+-dependent family. Na+ pumping/dependence is traced to node N and is therefore considered an ancestor of the N cluster (groups of B, C, and D clades).

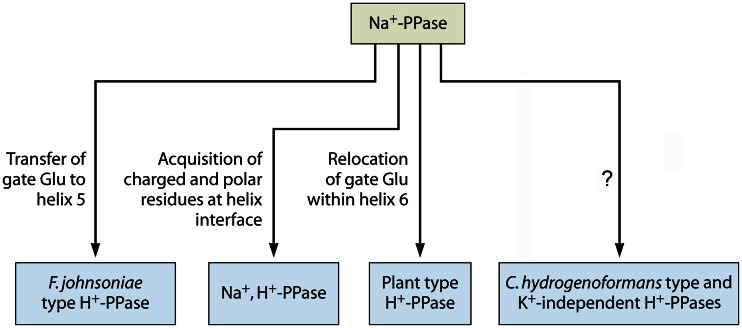

Overall, there appears to be strong evolutionary pressure to convert Na+-pumping PPases to H+-pumping PPases, supporting the primacy of membrane Na+ coupling versus H+ coupling (2, 50–52). Membrane PPase evolution apparently occurred via four different routes (Fig. 6). Each lineage of the K+-dependent H+-pumping PPases consists of enzymes that are structurally very similar and have a limited host species spectrum, indicating that the changes from Na+ to H+ specificity occurred relatively recently in the history of membrane PPases (Fig. 5). Two evolutionary routes, leading to plant-type and Flavobacterium johnsoniae-type H+-PPases, involved relocation of a gate-forming Glu residue (Glu246 in T. maritima Na+-PPase) to a position four residues further along transmembrane α-helix 6 or to α-helix 5, respectively (11). The relocated Glu occupies a position within the ion conductance channel and apparently retains a role in gating (14). F. johnsoniae PPase has close homologues only among Bacteroidetes, whereas the plant category of H+-PPases additionally includes enzymes from unicellular protists and the spirochete bacterium Leptospira. Interestingly, replacement of the gate Glu with Asp in Na+-PPase leads to a dramatic decrease in Na+-binding affinity, suggesting an additional function of this Glu as the cytoplasmic acceptor for transported Na+ (11).

Fig 6.

Four presumed routes from Na+ transport to H+ transport in membrane PPase.

Na+,H+-PPases represent the third evolutionary lineage leading to H+ transport, but in this case, the process is incomplete. Three proximate residues (Asp, Thr/Ser, and Phe) belonging to α-helices 3 and 4 appear to be specific to Na+,H+-PPases (12). Surprisingly, all three residues map to the outer circle of the α-helices rather than to the ion conductance channel and are located at the same depth in the membrane as the proposed gate in H+-PPase (Fig. 3A and B). Additionally, a Met residue corresponding to V. radiata PPase position 227 located close to the periplasmic end of α-helix 5, 10 to 14 Å away from the triad of the other Na+,H+-PPase-specific positions, is strongly conserved in this subfamily (12). Keeping in mind the overall similarity of the ion conductance channels in different PPases, these findings indicate that fine structural details are crucial for transport specificity; thus, small structural changes may be associated with subtle displacements of the inner-circle channel-forming helices, particularly in the gate area.

The plasticity of the ion conductance channel is further illustrated by the K+-dependent C. hydrogenoformans-type and K+-independent H+-PPases, which may represent the fourth route to H+ transport but have no clear structural determinants that impose H+ transport specificity. They all have a Glu residue in the same position as Na+-PPases and have no Asp, characteristic of Na+,H+-PPases, in α-helix 4. Based on the above-described findings, they would be expected to pump Na+; however, a previous study showed that they pump H+ but not Na+ (11).

Several rules can therefore be formulated to distinguish PPases with different cation specificities for the purposes of genome annotation. PPases with Lys at position 460 (C. hydrogenoformans PPase numbering) can be unequivocally classified as K+-independent H+-PPases. The presence of Ala at this position would indicate that the enzyme is K+ dependent, but such PPases may need to be placed on the phylogenetic tree for proper prediction of their cation specificities. In particular, Na+-PPases and C. hydrogenoformans-type H+-PPases cannot be distinguished solely by sequence analysis because both types have gate-forming Glu246 (T. maritima Na+-PPase numbering) residues. Fortunately, repositioning of this Glu is indicative of F. johnsoniae-type or plant-type H+-PPases. Furthermore, Na+,H+-PPases can be identified on the basis of a unique tetrad consisting of Asp146, Thr/Ser90, Phe94, and Met176 (B. vulgatus PPase numbering). Unbiased PPase sequence annotation would thus require comparison with the C. hydrogenoformans PPase sequence, comparison with the T. maritima and B. vulgatus PPase sequences, and (if necessary) phylogenetic analysis. In the available genome databases, Na+-PPases and Na+,H+-PPases are frequently misclassified as H+-PPases, and the annotation algorithms often omit or incorrectly predict the K+-mediated stimulation of PPase activity.

Delving deeper into membrane PPase history, protein segments formed by helices 3 to 6, 9 to 12, and 13 to 16 (T. maritima PPase numbering), which carry all of the functional residues, exhibit a similar structural motif (15, 53). This finding confirms that the membrane PPase ancestor arose through gene triplication, as proposed by Hedlund et al. (54).

WHY DO CELLS NEED MEMBRANE PPases?

The finding that membrane PPase can act as a hydrolase follows from data showing that H+-PPases of the bacterium Chloroflexus aurantiacus and the plant Arabidopsis thaliana, expressed from autonomous plasmids, functionally complement the deficiency of soluble PPase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (55). Moreover, soluble PPase restores normal postgerminative heterotrophic growth in seedlings of H+-PPase-deficient A. thaliana (56). However, PPi removal does not seem to be the major function of membrane PPase because the species rarely, if ever, rely on this enzyme as the sole PPi disposal system. Sequenced genomes containing membrane PPases additionally include genes for soluble PPases, which catalyze energy-dissipating hydrolysis of PPi. Soluble PPase belonging to any of its three unrelated families (57, 58) may coexist with a membrane PPase(s), but family I PPase is the most frequent companion. Of family II PPases, only the regulatable subfamily, whose members contain nucleotide-binding CBS domains (59), coexists with membrane PPases. Low-activity (kcat/Km ≈ 105 M−1 s−1) family III (haloalkanoate dehalogenase superfamily) PPases occur only in the phylum Bacteroidetes (58), to which most Na+,H+-PPases belong (12).

Na+/H+ transport function is also not unique to membrane PPase insofar as cells contain ATPases and other proteins capable of translocating the same cations. Why, then, does every fourth prokaryotic species contain a membrane PPase? Several lines of evidence suggest that this enzyme is an auxiliary device for mobilizing PPi energy so as to maintain cation gradients and thereby help cells survive under stress conditions. First, organisms possessing membrane PPase genes tend to frequently encounter environmental conditions that severely constrain cell energy status. The “choice” between H+- and Na+-PPases generally depends on whether H+ or Na+ is used as the coupling ion in the particular organism. The presence of both H+- and Na+-PPases or a Na+,H+-PPase may be considered the utmost in mobilization and versatility of PPi-based energetics. Notably, the robust archaeon M. acetivorans contains not only Na+-PPase and H+-PPase but also a dual-specificity F1Fo ATP synthase (Na+,H+-ATPase) (41). Second, experiments with the photosynthetic bacterium R. rubrum indicated that the H+-PPase gene is expressed throughout all growth phases under anaerobic conditions (60), but its expression level declines progressively in the transition to aerobic conditions in both photosynthetic and fermentative cultures but again increases upon exposure to salt (5, 60). Similarly, exposure of plants to anoxia, cold, drought, salt, or nutrient limitation increases the abundance and activity of H+-PPase (61–65). Third, disruption of the H+-PPase gene in R. rubrum yields a mutant strain that is able to grow normally using anaerobic photosynthesis under high-intensity light, shows a long delay prior to proliferation at intermediate light levels, and fails to grow at low light levels (66). Under aerobic conditions, the mutant demonstrates a similar dependence of growth on oxygen pressure. In a similar manner, downregulation of H+-PPase in trypanosomes affected their growth and ability to respond to stressful conditions (67).

Accordingly, introduction of the H+-PPase gene makes E. coli cells tolerant to various abiotic stresses, including heat shock and exposure to hydrogen peroxide, NaCl, or metal cations (68), and confers salt tolerance to S. cerevisiae strains deficient in the Na+/H+ exchanger (69) or mitochondrial PPase (68). Similarly, diverse model and agricultural plants engineered to overexpress plant H+-PPases (70–72) or even bacterial H+-PPase (73) are notably salt and drought tolerant. These mutant plants also outperform controls when grown with limited phosphorus (65). Importantly, no such effects are observed with plants that overexpress the gene for soluble PPase (74). Thus, H+-PPase has emerged as a promising tool for engineering of stress-resistant organisms (75).

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Membrane PPases are homodimeric transport proteins that utilize PPi energy to sustain monovalent cation gradients in prokaryotes, plants, and protists. In prokaryotes, monophyletic Na+,H+-transporting and polyphyletic H+-transporting subfamilies have independently evolved from an ancestral Na+-transporting PPase. Changes in transport specificity appear to involve modulation of the channel gate via a distantly induced conformational change or relocation of the gate Glu. All membrane PPases have a unique structure with a proximate PPi hydrolysis site and ion conductance channel. The transport process is apparently triggered by a proton generated from the nucleophilic water during PPi hydrolysis and reflects the physical movement of a hydrated cation between acidic groups located along the channel. However, further structural data are needed to identify Na+-binding sites, the role of K+ in Na+ transport, and other details of the translocation mechanism.

Expression of H+-PPase genes in different organisms increases these organisms' stress tolerance. Available data suggest that this effect results, at least in part, from indirect modulation of Na+ transport across membranes via increased proton motive force. These findings suggest that Na+-PPases, and particularly Na+,H+-PPase, are promising candidates for construction of transgenic stress-resistant plants and other organisms. On the other hand, the breakthrough in membrane PPase structural biology provides unexplored opportunities for the design of drugs that impede the survival of pathogenic bacteria and protists having membrane PPases as a defense mechanism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (grant 12-04-01002), the Academy of Finland (grant 139031), and the Ministry of Education and the Academy of Finland for the National Graduate School in Informational and Structural Biology.

REFERENCES

- 1. Baltscheffsky H. 1996. Energy conversion leading to the origin and early evolution of life: did inorganic pyrophosphate precede adenosine triphosphate?, p 1–9 In Baltscheffsky H. (ed), Origin and evolution of biological energy conversion. VCH, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 2. Holm NG, Baltscheffsky H. 2011. Links between hydrothermal environments, pyrophosphate, Na+, and early evolution. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 41:483–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Heinonen JK. 2001. Biological role of inorganic pyrophosphate. Kluwer Academic Publishers, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 4. Seufferheld MJ, Kim KM, Whitfield J, Valerio A, Caetano-Anollés G. 2011. Evolution of vacuolar proton pyrophosphatase domains and volutin granules: clues into the early evolutionary origin of the acidocalcisome. Biol. Direct 6:50 doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-6-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baltscheffsky H, Von Stedingk LV, Heldt HW, Klingenberg M. 1966. Inorganic pyrophosphate: formation in bacterial photophosphorylation. Science 153:1120–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baltscheffsky M. 1967. Inorganic pyrophosphate and ATP as energy donors in chromatophores from Rhodospirillum rubrum. Nature 216:241–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Docampo R, Moreno SN. 2011. Acidocalcisomes. Cell Calcium 50:113–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Seufferheld M, Lea CR, Vieira M, Oldfield E, Docampo R. 2004. The H+-pyrophosphatase of Rhodospirillum rubrum is predominantly located in polyphosphate-rich acidocalcisomes. J. Biol. Chem. 279:51193–51202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Seufferheld MJ, Vieira MC, Ruiz FA, Rodrigues CO, Moreno SN, Docampo R. 2003. Identification of organelles in bacteria similar to acidocalcisomes of unicellular eukaryotes. J. Biol. Chem. 278:29971–29978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Malinen AM, Belogurov GA, Baykov AA, Lahti R. 2007. Na+-pyrophosphatase: a novel primary sodium pump. Biochemistry 46:8872–8878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Luoto H, Belogurov GA, Baykov AA, Lahti R, Malinen AM. 2011. Na+-translocating membrane pyrophosphatases are widespread in the microbial world and evolutionarily preceded H+-translocating pyrophosphatases. J. Biol. Chem. 286:21633–21642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Luoto H, Baykov AA, Lahti R, Malinen AM. 2013. Membrane-integral pyrophosphatase subfamily capable of translocating both Na+ and H+. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110:1255–1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Belogurov GA, Lahti R. 2002. A lysine substitute for K+. A460K mutation eliminates K+ dependence in H+-pyrophosphatase of Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans. J. Biol. Chem. 277:49651–49654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lin SM, Tsai JY, Hsiao CD, Huang YT, Chiu CL, Liu MH, Tung JY, Liu TH, Pan RL, Sun YJ. 2012. Crystal structure of a membrane-embedded H+-translocating pyrophosphatase. Nature 484:399–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kellosalo J, Kajander T, Kogan K, Pokharel K, Goldman A. 2012. The structure and catalytic cycle of a sodium-pumping pyrophosphatase. Science 337:473–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Drozdowicz YM, Lu YP, Patel V, Fitz-Gibbon S, Miller JH, Rea PA. 1999. A thermostable vacuolar-type membrane pyrophosphatase from the archaeon Pyrobaculum aerophilum: implications for the origins of pyrophosphate-energized pumps. FEBS Lett. 460:505–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Belogurov GA, Turkina MV, Penttinen A, Huopalahti S, Baykov AA, Lahti R. 2002. H+-pyrophosphatase of Rhodospirillum rubrum: high-yield expression in Escherichia coli and identification of the Cys residues responsible for inactivation by mersalyl. J. Biol. Chem. 277:22209–22214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baltscheffsky M, Schultz A, Baltscheffsky H. 1999. H+-PPases: a tightly membrane-bound family. FEBS Lett. 457:527–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Maeshima M. 2000. Vacuolar H+-pyrophosphatase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1465:37–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Drozdowicz YM, Rea PA. 2001. Vacuolar H+-pyrophosphatases: from the evolutionary backwaters into the mainstream. Trends Plant Sci. 6:206–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Docampo R, de Souza W, Miranda K, Rohloff P, Moreno SN. 2005. Acidocalcisomes—conserved from bacteria to man. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:251–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Serrano A, Pérez-Castiñeira JR, Baltscheffsky M, Baltscheffsky H. 2007. H+-PPases: yesterday, today and tomorrow. IUBMB Life 59:76–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moyle J, Mitchell R, Mitchell P. 1972. Proton-translocating pyrophosphatase of Rhodospirillum rubrum. FEBS Lett. 23:233–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pérez-Castiñeira JR, Alvar J, Ruiz-Pérez LM, Serrano A. 2002. Evidence for a wide occurrence of proton-translocating pyrophosphatase genes in parasitic and free-living protozoa. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 294:567–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Docampo R, Moreno SNJ. 2008. The acidocalcisome as a target for chemotherapeutic agents in protozoan parasites. Curr. Pharm. Des. 14:882–888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kellosalo J, Kajander T, Honkanen R, Goldman A. 2012. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of membrane-bound pyrophosphatases. Mol. Membr. Biol. 30:64–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mimura H, Nakanishi Y, Hirono M, Maeshima M. 2004. Membrane topology of the H+-pyrophosphatase of Streptomyces coelicolor determined by cysteine-scanning mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 279:35106–35112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hirono M, Nakanishi Y, Maeshima M. 2007. Essential amino acid residues in the central transmembrane domains and loops for energy coupling of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) H+-pyrophosphatase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1767:930–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hirono M, Nakanishi Y, Maeshima M. 2007. Identification of amino acid residues participating in the energy coupling and proton transport of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) H+-pyrophosphatase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1767:1401–1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Belogurov GA, Malinen AM, Turkina MV, Jalonen U, Rytkönen K, Baykov AA, Lahti R. 2005. Membrane-bound pyrophosphatase of Thermotoga maritima requires sodium for activity. Biochemistry 44:2088–2096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Biegel E, Müller V. 2011. A Na+-translocating pyrophosphatase in the acetogenic bacterium Acetobacterium woodii. J. Biol. Chem. 286:6080–6084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Malinen AM, Baykov AA, Lahti R. 2008. Mutual effects of cationic ligands and substrate on activity of the Na+-transporting pyrophosphatase of Methanosarcina mazei. Biochemistry 47:13447–13454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sato MH, Kasahara M, Ishii N, Homareda H, Matsui H, Yoshida M. 1994. Purified vacuolar inorganic pyrophosphatase consisting of a 75-kDa polypeptide can pump H+ into reconstituted proteoliposomes. J. Biol. Chem. 269:6725–6728 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ros R, Romieu C, Gibrat R, Grignon C. 1995. The plant inorganic pyrophosphatase does not transport K+ in vacuole membrane vesicles multilabeled with fluorescent probes for H+, K+, and membrane potential. J. Biol. Chem. 270:4368–4374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Baykov AA, Dubnova EB, Bakuleva NP, Evtushenko OA, Zhen R-G, Rea PA. 1993. Differential sensitivity of membrane-associated pyrophosphatases to inhibition by diphosphonates and fluoride delineates two classes of enzyme. FEBS Lett. 2:199–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kakinuma Y. 1998. Inorganic cation transport and energy transduction in Enterococcus hirae and other streptococci. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1021–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hara Y, Yamada J, Nakao M. 1986. Proton transport catalyzed by the sodium pump. Ouabain-sensitive ATPase activity and the phosphorylation of Na,K-ATPase in the absence of sodium ions. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 99:531–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Laubinger W, Dimroth P. 1989. The sodium ion translocating adenosinetriphosphatase of Propionigenium modestum pumps protons at low sodium ion concentrations. Biochemistry 28:7194–7198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Reidlinger J, Müller V. 1994. Purification of ATP synthase from Acetobacterium woodii and identification as a Na+-translocating F1Fo-type enzyme. Eur. J. Biochem. 223:275–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dimroth P. 1997. Primary sodium ion translocating enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1318:11–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schlegel K, Leone V, Faraldo-Gómez JD, Müller V. 2012. Promiscuous archaeal ATP synthase concurrently coupled to Na+ and H+ translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:947–952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fabrichniy IP, Lehtiö L, Tammenkoski M, Zyryanov AB, Oksanen E, Baykov AA, Lahti R, Goldman A. 2007. A trimetal site and substrate distortion in a family II inorganic pyrophosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 282:1422–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Heikinheimo P, Tuominen V, Ahonen A-K, Teplyakov A, Cooperman BS, Baykov AA, Lahti R, Goldman A. 2001. Towards a quantum-mechanical description of metal assisted phosphoryl transfer in pyrophosphatase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:3121–3126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Belogurov GA, Fabrichniy IP, Pohjanjoki P, Kasho VN, Lehtihuhta E, Turkina MV, Cooperman BS, Goldman A, Baykov AA, Lahti R. 2000. Catalytically important ionizations along the reaction pathway of yeast pyrophosphatase. Biochemistry 39:13931–13938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Buch-Pedersen MJ, Pedersen BP, Veierskov B, Nissen P, Palmgren MG. 2009. Protons and how they are transported by proton pumps. Pflügers Arch. 457:573–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eigen M. 1964. Proton transfer, acid-base catalysis and enzymatic hydrolysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 3:1–19 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zundel G, Metzger H. 1968. Energiebänder der tunnelnden Überschuß-Protonen in flüssigen Säuren. Eine IR-spektroskopische Untersuchung der Natur der Gruppierungen H5O2+. Z. Physik Chem. 58:225–245 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mitchell P. 1974. A chemiosmotic molecular mechanism for proton-translocating adenosine triphosphatase. FEBS Lett. 43:189–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Boyer PD. 1989. A perspective of the binding change mechanism for ATP synthesis. FASEB J. 3:2164–2178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mulkidjanian AY, Galperin MY, Koonin EV. 2009. Co-evolution of primordial membranes and membrane proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 34:206–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mulkidjanian AY, Galperin MY, Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. 2008. Evolutionary primacy of sodium bioenergetics. Biol. Direct 3:13 doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-3-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mulkidjanian AY, Dibrov P, Galperin MY. 2008. The past and present of sodium energetics: may the sodium-motive force be with you. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777:985–992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Au KM, Barabote RD, Hu KY, Saier MH., Jr 2006. Evolutionary appearance of H+-translocating pyrophosphatases. Microbiology 152:1243–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hedlund J, Cantoni R, Baltscheffsky M, Baltscheffsky H, Persson B. 2006. Analysis of ancient sequence motifs in the H+-PPase family. FEBS J. 273:5183–5193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pérez-Castiñeira JR, López-Marques RL, Villalba JM, Losada M, Serrano A. 2002. Functional complementation of yeast cytosolic pyrophosphatase by bacterial and plant H+-translocating pyrophosphatases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:15914–15919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 56. Ferjani A, Segami S, Horiguchi G, Muto Y, Maeshima M, Tsukaya H. 2011. Keep an eye on PPi: the vacuolar-type H+-pyrophosphatase regulates postgerminative development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23:2895–2908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sivula T, Salminen A, Parfenyev AN, Pohjanjoki P, Goldman A, Cooperman BS, Baykov AA, Lahti R. 1999. Evolutionary aspects of inorganic pyrophosphatase. FEBS Lett. 439:263–266 [Google Scholar]

- 58. Huang H, Patskovsky Y, Toro R, Farelli JD, Pandya C, Almo SC, Allen KN, Dunaway-Mariano D. 2011. Divergence of structure and function in the haloacid dehalogenase enzyme superfamily: Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron BT2127 is an inorganic pyrophosphatase. Biochemistry 50:8937–8949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jämsen J, Tuominen H, Salminen A, Belogurov GA, Magretova NN, Baykov AA, Lahti R. 2007. A CBS domain-containing pyrophosphatase of Moorella thermoacetica is regulated by adenine nucleotides. Biochem. J. 408:327–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. López-Marques RL, Pérez-Castiñeira JR, Losada M, Serrano A. 2004. Differential regulation of soluble and membrane-bound inorganic pyrophosphatases in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum provides insights into pyrophosphate-based stress bioenergetics. J. Bacteriol. 186:5418–5426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Colomb R, Cerana R. 1993. Enhanced activity of tonoplast pyrophosphatase in NaCl-grown cells of Daucus carota. J. Plant Physiol. 142:226–229 [Google Scholar]

- 62. Carystinos GD, MacDonald HR, Monroy AF, Dhindsa RS, Poole RJ. 1995. Vacuolar H+-translocating pyrophosphatase is induced by anoxia or chilling in seedlings of rice. Plant Physiol. 108:641–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Palma DA, Blumwald E, Plaxton WC. 2000. Upregulation of vacuolar H+-translocating pyrophosphatase by phosphate starvation of Brassica napus (rapeseed) suspension cell cultures. FEBS Lett. 486:155–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fukuda A, Chiba K, Maeda M, Nakamura A, Maeshima M, Tanaka Y. 2004. Effect of salt and osmotic stresses on the expression of genes for the vacuolar H+-pyrophosphatase, H+-ATPase subunit A, and Na+/H+ antiporter from barley. J. Exp. Bot. 55:585–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yang H, Knapp J, Koirala P, Rajagopal D, Peer WA, Silbart LK, Murphy A, Gaxiola RA. 2007. Enhanced phosphorus nutrition in monocots and dicots over-expressing a phosphorus-responsive type I H+-pyrophosphatase. Plant Biotechnol. J. 5:735–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Garcia-Contreras R, Celis H, Romero I. 2004. Importance of Rhodospirillum rubrum H+-pyrophosphatase under low-energy conditions. J. Bacteriol. 186:6651–6655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lemercier G, Dutoya S, Luo S, Ruiz FA, Rodrigues CO, Baltz T, Docampo R, Bakalara N. 2002. A vacuolar-type H+-pyrophosphatase governs maintenance of functional acidocalcisomes and growth of the insect and mammalian forms of Trypanosoma brucei. J. Biol. Chem. 277:37369–37376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yoon HS, Kim SY, Kim IS. 2013. Stress response of plant H+-PPase-expressing transgenic Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a potentially useful mechanism for the development of stress-tolerant organisms. J. Appl. Genet. 54:129–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gaxiola RA, Rao R, Sherman A, Grisafi P, Alper SL, Fink GR. 1999. The Arabidopsis thaliana proton transporters, AtNhx1 and Avp1, can function in cation detoxification in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:1480–1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Gaxiola RA, Li J, Undurraga S, Dang LM, Allen GJ, Alper SL, Fink GR. 2001. Drought- and salt-tolerant plants result from overexpression of the AVP1 H+-pump. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:11444–11449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Guo S, Yin H, Zhang X, Zhao F, Li P, Chen S, Zhao Y, Zhang H. 2006. Molecular cloning and characterization of a vacuolar H+-pyrophosphatase gene, SsVP, from the halophyte Suaeda salsa and its overexpression increases salt and drought tolerance of Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 60:41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lv S, Zhang K, Gao Q, Lian L, Song Y, Zhang J. 2008. Overexpression of an H+-PPase gene from Thellungiella halophila in cotton enhances salt tolerance and improves growth and photosynthetic performance. Plant Cell Physiol. 49:1150–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. D'yakova EV, Rakitin AL, Kamionskaya AM, Baikov AA, Lahti R, Ravin NV, Skryabin KG. 2006. A study of the effect of expression of the gene encoding the membrane H+-pyrophosphatase of Rhodospirillum rubrum on salt resistance of transgenic tobacco plants. Dokl. Biol. Sci. 409:346–348 [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sonnewald U. 1992. Expression of E. coli inorganic pyrophosphatase in transgenic plants alters photoassimilate partitioning. Plant J. 2:571–581 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gaxiola RA, Sanchez CA, Paez-Valencia J, Ayre BG, Elser JJ. 2012. Genetic manipulation of a “vacuolar” H+-PPase: from salt tolerance to yield enhancement under phosphorus-deficient soils. Plant Physiol. 159:3–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]