Abstract

Neuroblastoma, the most common extra-cranial solid tumor in infants and children, is characterized by a high rate of spontaneous remissions in infancy. Retinoic acid (RA) has been known to induce neuroblastoma differentiation; however, the molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways that are responsible for RA-mediated neuroblastoma cell differentiation remain unclear. Here, we sought to determine the cell signaling processes involved in RA-induced cellular differentiation. Upon RA administration, human neuroblastoma cell lines, SK-N-SH and BE(2)-C, demonstrated neurite extensions, which is an indicator of neuronal cell differentiation. Moreover, cell cycle arrest occurred in G1/G0 phase. The protein levels of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, p21 and p27Kip, which inhibit cell proliferation by blocking cell cycle progression at G1/S phase, increased after RA treatment. Interestingly, RA promoted cell survival during the differentiation process, hence suggesting a potential mechanism for neuroblastoma resistance to RA therapy. Importantly, we found that the PI3K/AKT pathway is required for RA-induced neuroblastoma cell differentiation. Our results elucidated the molecular mechanism of RA-induced neuroblastoma cellular differentiation, which may be important for developing novel therapeutic strategy against poorly differentiated neuroblastoma.

Keywords: PI3K, ERK, Retinoic acid, Differentiation, Neuroblastoma

INTRODUCTION

Neuroblastoma is derived from embryonal neural crest cells and is the most common extra-cranial tumor in infants and children. It is biologically heterogeneous, hence lending to a wide spectrum of clinical presentations. Most notably, it is characterized by a propensity to differentiate and even spontaneously regress when diagnosed in infancy. Pharmacologic agents can also induce neuroblastoma regression. For example, retinoic acid (RA) is used clinically for its ability to induce cellular differentiation. RA, the biologically active form of vitamin A, is a natural morphogen and plays an important role in the early embryonic development and differentiation of the nervous system [1]. RA can also suppress malignant cell growth by induction of cell cycle arrest, differentiation, or apoptosis. However, in some cases, RA not only fails to inhibit tumor cell growth, but can also enhance cell proliferation and survival [1,2].

Biological effects of RA are mediated by binding all-trans-RA (ATRA) and retinoid X (9-cis-RA) receptors (RARs and RXRs), respectively. These nuclear receptors are activated by RA to form RXR-RAR heterodimers [1] resulting in induction of tumor suppressor gene expression [3] such as RARr, p21Cip1, p27Kip1, thioredoxin reductase and interferon-regulatory factor-1 [4]. RXR-RAR modulates expression of retinoid-responsive genes in two ways: (i) by binding to RA response element (RARE) in promoter regions of target genes or (ii) by antagonizing the enhancer action of transcription factors, such as AP1 or NF-IL6. RA can also act via nuclear receptor independent pathways, in which retinoid-related molecules that do not bind to classical retinoid receptors can induce apoptosis through caspase activation [5].

RA derivatives are used in therapy against neuroblastoma, and show promising clinical results [6,7]; however, the overall survival, unfortunately, has remained short of anticipated. Therefore, it is vital to elucidate the cellular mechanisms that are involved in RA-induced neuroblastoma differentiation. In particular, discerning the potential role of RA-mediated compensatory signaling pathways that lead to cell survival and evasion of apoptosis may shed some important information as to their perplexing clinical results. Activated by various growth factors, the PI3K/AKT signaling cascade is an important cell survival pathway, which can also regulate differentiation process of various cells [8]. Overexpression of constitutively active PI3K induces neurite outgrowth and expression of neuronal markers [9]. RA-induced activation of Rac1, a GTPase involved in cell growth and cytoskeleton remodeling, has been shown to be regulated by phosphorylation of p85 regulatory subunit by Src kinase in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells [10]. The PI3K inhibitor, LY294002, blocks RA-induced neurite outgrowth and expression of neuronal markers, suggesting that activation of PI3K/Rac1 signaling in involved in the regulation of neuronal differentiation [11]. The ERK1/2 pathway is another signaling cascade that can be activated by mitogens, and cytokines to stimulate cell proliferation [12]. Aberrant activations of both PI3K and ERK1/2 pathways are observed in various cancers, hence, they are important potential targets for anti-cancer therapy [13,14]. Moreover, the PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 pathways are critically involved in the regulation of apoptosis [15].

In this study, we investigated the effects of RA on neuroblastoma cell signaling processes. RA treatment increased expressions of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor, p21 and p27Kip and halted cell cycle progression. Interestingly, we found upregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins, Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, with RA treatment, implying potential mechanisms of RA-resistance and clinical treatment failures in patients with neuroblastoma. Moreover, the PI3K/AKT activity was critical in RA-induced neurite elongation and cellular differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All-trans-RA and β-actin antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). DNA fragmentation and cell cycle analysis kits were obtained from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN). The inhibitors, LY294002 and U0126, and antibodies against phospho-AKT, AKT, PTEN, Bad, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, p21, p27Kip, phospho-ERK1/2, ERK1/2 were purchased from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA). Anti-neuron specific enolase (NSE) was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Antibodies against N-Ras, K-Ras, β-actin, and all secondary antibodies against mouse and rabbit IgG were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). The TransLucent RXR Reporter Vector was purchased from Panomics (Redwood City, CA).

Cell culture and transfection assays

Human neuroblastoma cell lines, SK-N-SH and BE(2)-C, were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 media (Cellgro Mediatech Inc., Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma Aldrich) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. For transfections, 5 × 104 cells were seeded per well in a 24-well plate and transfected the next day with Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen, Rockville, MD). Cells were harvested at indicated time points, and luciferase activity assay was performed with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI). Luciferase activity was measured by Luminometer Monolight 2010 (Analytical Luminescence Laboratory, San Diego, CA) and normalized to Renilla luciferase activity using the same samples. Cells were seeded on culture plates, serum-starved for 24 h and then treated with RA. RA concentration of 10 µM was used based on phase I clinical trial data in patients with neuroblastoma [7]. Morphologic neurite formation was assessed daily with a Nikon inverted phase-contrast microscope (Nikon Eclipse TS100).

Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle distribution was analyzed by flow cytometry. Briefly, 1 × 106 cells were trypsinized, washed once with PBS, and fixed in 70% ethanol. Fixed cells were again washed with PBS, incubated with 100 µg/ml RNase for 30 min at 37°C, stained with propidium iodide (50 µg/ml), and analyzed on a FACScan flow cytometer. The percentage of cells in different cell cycle phases was analyzed using Cell-FIT software (Becton-Dickinson Instruments, San Jose, CA).

Cell survival and cell death assays

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 5–10 × 103 cells/well in RPMI 1640 culture media with 10% FBS and incubated overnight. They were then cultured in serum-free RPMI media overnight and treated with RA (10 µM). Cell survival was assessed daily using the Cell-Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). The values were read at OD450 with the EL808 Ultra Microplate Reader (Bio Tek Instrument, Inc., Winooski, VT). DNA fragmentation was measured as previously described [16]. Cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragments (mono- and oligonucleosomes) were detected using a Cell Death Detection ELISAplus kit (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Each assay was performed in triplicate.

Western blot analysis

Protein concentrations were quantified using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay kit (Hercules, CA). Equal amounts of protein were fractionated by electrophoresis on 4–12% NuPAGE Novex Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen), transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with antibodies. The bands were visualized by an enhanced chemiluminescent detection system (ECL Plus) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Amersham Inc., Piscataway, NJ).

RESULTS

RA induced neuroblastoma cellular differentiation by G0/G1 cell arrest

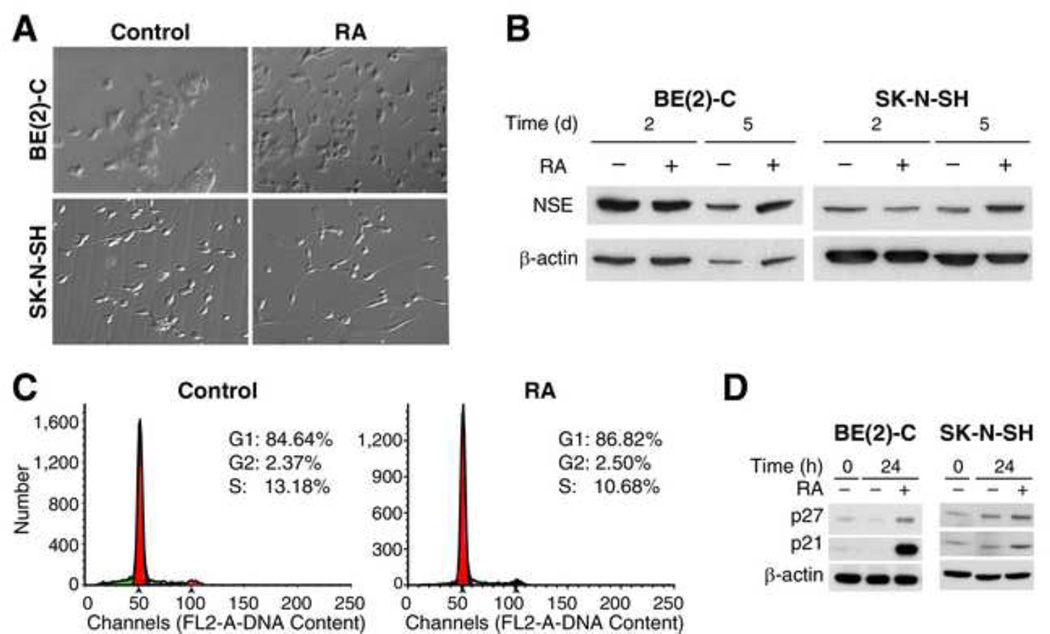

The basis for therapeutic application of RA is its ability to induce tumor cell differentiation followed by cell death. Thus, we first examined the effects of RA on neuroblastoma cellular differentiation. In both SK-N-SH and BE(2)-C human neuroblastoma cell lines grown in serum-free RPMI media, a very little evidence of cell differentiation was observed at baseline (Fig. 1A, left). However, with administration of RA (10 µM), cells exhibited distinct morphological changes consistent with differentiation as evidenced by development of long, out-branched neurites (Fig. 1A, right). Correlative to morphologic evidence, the expression of NSE, a marker of neuroendocrine cellular differentiation, also increased significantly at 5 days after treatment with RA (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. RA induced neuroblastoma cellular differentiation by G0/G1 cell arrest.

BE(2)-C and SK-N-SH human neuroblastoma cells were cultured in RPMI with 10% FBS, and treated with RA (10 µM) for 24 h after serum starvation. (A) RA treatment resulted in the cellular differentiation characterized by a polar appearance with longer, out-branched neuritis (right panels). (B) NSE protein levels increased after RA (10 µM). (C) The percentage of cells at S-phase decreased from 13.2% to 10.7% after RA (10 µM) for 24 h in SK-N-SH cells. (D) RA significantly increased expressions of CDK inhibitors, p21 and p27Kip, in both cell lines.

RA induction of cellular differentiation is preceded by cell cycle arrest [17]. To investigate the effects of RA on cell cycle progression, we next measured the distribution of cells in cell cycle phases using flow cytometry. After serum starvation for 24 h, SK-N-SH cells demonstrated cell cycle arrest with 84.64% of cells in G1 phase. When treated with RA, the percentage of SK-N-SH cells in G1 phase increased to 86.82%. The percentage of cells in S phase decreased from 13.18% to 10.68% (Fig. 1C). RA also increased cells in G1 phase from 76.23% to 77.60% when assessed under without serum starvation (data not shown). Thus, RA treatment consistently induced neuroblastoma cell cycle arrest. Expressions of CDK inhibitors p21 and p27Kip, which are thought to be important in regulating the G1 phase checkpoint [18], were measured by western blotting. Both p21 and p27Kip protein levels significantly increased at 24 h after RA treatment (Fig. 1D). These results demonstrate that SK-N-SH and BE(2)-C cell cycle arrest is induced by RA, and that p21 and p27Kip are critically involved in this process.

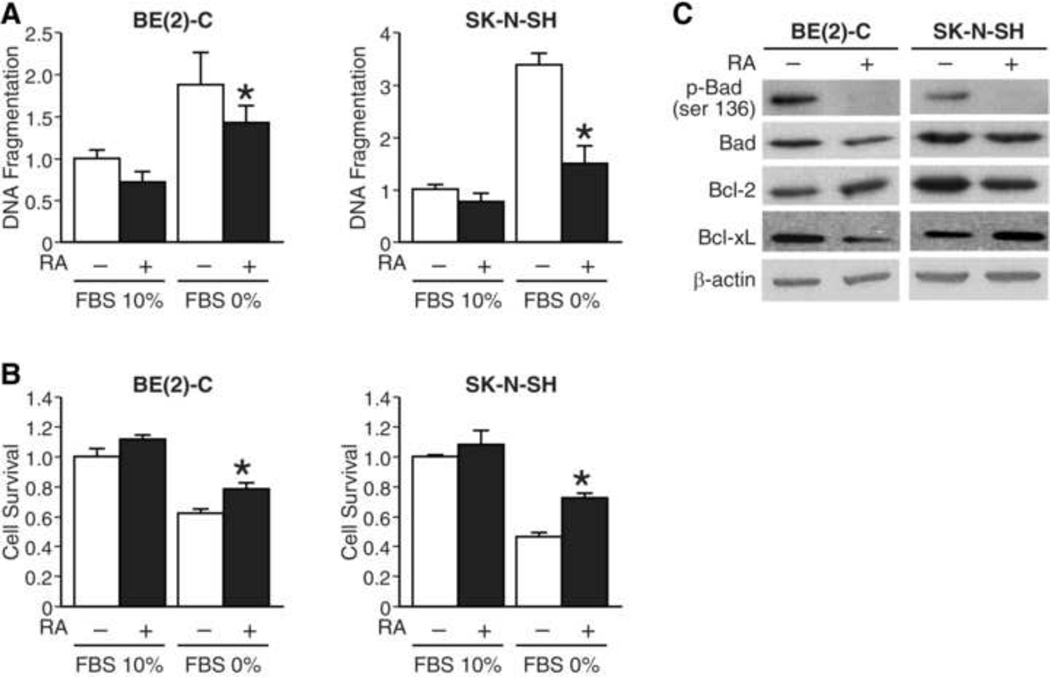

RA attenuated serum-starved apoptosis and stimulated cell survival

Since RA treatment induced cell growth arrest, we sought to determine the effects of RA on cell survival and apoptosis. Cells were treated with RA in RPMI media with either serum-free or 10% FBS condition. We first measured DNA fragmentation in both cell lines, and found that RA significantly reduced serum starvation-induced apoptosis by 20% and 56% in BE(2)-C and SK-N-SH cells, respectively (Fig. 2A). We next determined the effects of RA on cell survival. We found that RA modestly increased the cell viability by 22% and 28% in BE(2)-C and SK-N-SH cells, respectively (Fig. 2B). We then examined the expression of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins after RA treatment by Western blot analysis. We found that RA significantly decreased p-Bad (ser136) protein levels in both cell lines (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, levels of anti-apoptotic proteins, Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, were variably affected by RA treatment (Fig. 2C). There were slight increase in expression of Bcl-2 and decrease in Bcl-xL after RA in BE(2)-c cells. However, these changes were reversed in SK-N-SH cells in which Bcl-2 decreased and Bcl-xL increased after RA treatment. Moreover, RA attenuated expression of PTEN, an endogenous inhibitor of PI3K, during serum starvation (data not shown). Therefore, our findings indicate a potential novel cell protective function of RA, which in part maybe mediated by PI3K pathway, during serum-starvation-induced apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells.

Figure 2. RA attenuated serum-starved apoptosis and stimulated cell survival.

(A) As expected, DNA fragmentation increased with serum-starved cell culture media. This was significantly attenuated in the presence of RA (10 µM) for 24 h in both BE(2)-C and SK-N-SH cells (*=p<0.05 vs. no RA). (B) Conversely, RA (10 µM) stimulated cell survival with serum starvation cell culture condition in both cell lines (*=p<0.05 vs. no RA). (C) RA (10 µM) treatment decreased expression of phosphorylated Bad (p-Bad) relative to total Bad. There were slight increase in Bcl-2 and decrease in Bcl-xL protein levels after RA in BE(2)-C; these were reversed in SK-N-SH cells, respectively. β-actin demonstrates equal protein loading.

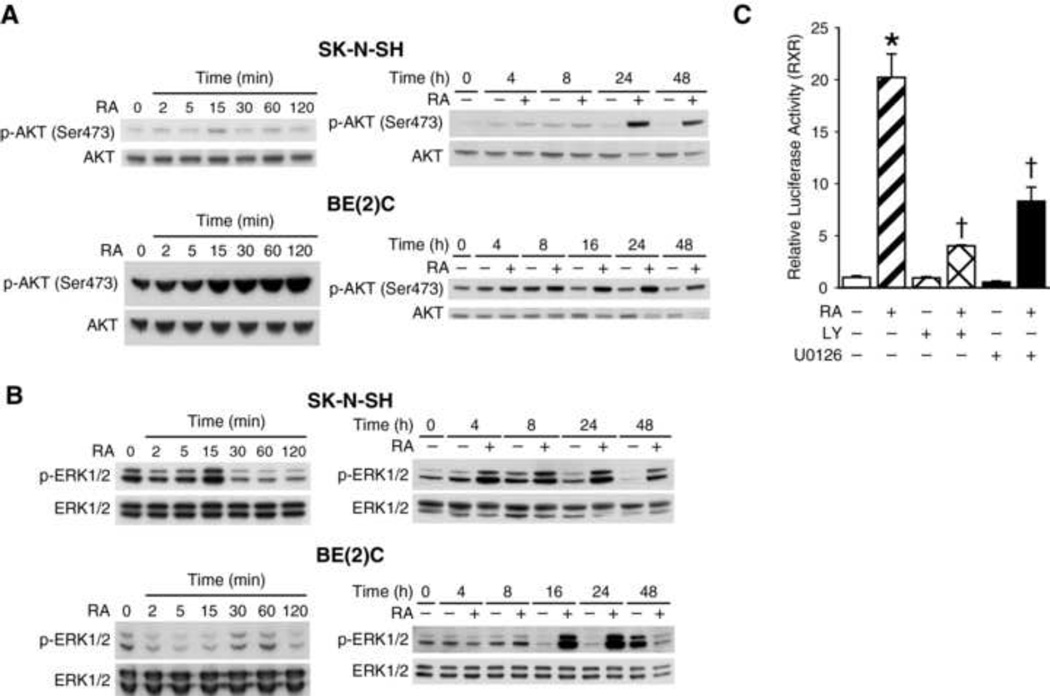

RA phosphorylated AKT &ERK1/2 and PI3K & MAPK regulated RXR transcription activity

To identify signaling pathways responsible for RA-induced decrease in cellular apoptosis and increase in neuroblastoma cell survival, we examined two critical signaling pathways in neuroblastoma, namely, PI3K an MAPK. We determined the effects of RA on PI3K and MAPK pathways in SK-N-SH and BE(2)-C cells by measuring phosphorylation of AKT and ERK1/2 by Western blot analysis. Phosphorylated AKT (Ser473) levels increased in a time-dependent manner after RA treatment in both cell lines (Fig. 3A). In BE(2)-C cells, RA treatment (10 µM) showed a rapid steady increase in p-AKT starting at 15 min, followed by a sustained increase from 16 to 48 h time points. Similar to BE(2)-C cells, there were also increases in p-AKT after RA treatment in SK-N-SH cells. Consistent with p-AKT, phospho-ERK1/2 levels also increased after RA treatment with expression peaking at 24 h in both cell lines (Fig. 3B). To further confirm the role of PI3K and MAPK signal transduction pathways in RA-induced neuroblastoma differentiation, we used RXRE luciferase reporter to determine the effects of these pathways on the transcriptional activity of RA in neuroblastoma cells. The RXRE site is a nuclear transcription factor-binding site on the promoter regions of RA target genes. RA activates its heterodimer nuclear receptors RXR/RAR, which then bind to RXRE site to induce transcription of RA target proteins. Our results showed that RXR-luciferase activity was increased by > 20-fold when cells were treated with RA for 24 h (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, RA-induced RXR-luciferase activity was significantly attenuated by treatment with inhibitor of either PI3K or ERK pathway, LY294002 or U0126, respectively (Fig. 3C). Therefore, we conclude that PI3K and ERK1/2 activation positively regulates RXRE-transcriptional activity.

Figure 3. RA phosphorylated AKT & ERK1/2 and PI3K & MAPK regulated RXR transcription activity.

(A) RA (10 µM) rapidly increased phosphorylation of AKT (ser473), a downstream effector of PI3K, at 15 min and peaking at 24 h in SK-N-SH cells, while there was a more steady-state increases in BE(2)-C cells. Total AKT expression showed relatively equal protein loading. (B) RA (10 µM) also increased levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2) transiently at 15 and 30 min in SK-N-SH and BE(2)-C, respectively; it also peaked at 24 h after RA treatment. (C) The RXR-luciferase activity was significantly increased by > 20-fold in SK-N-SH cells with RA (10 µM) treatment. This induction was inhibited with LY, an inhibitor of PI3K (*=p<0.05 vs. no treatment; †=p<0.05 vs. RA alone), and only partially attenuated with U0126, an inhibitor of MEK1/2.

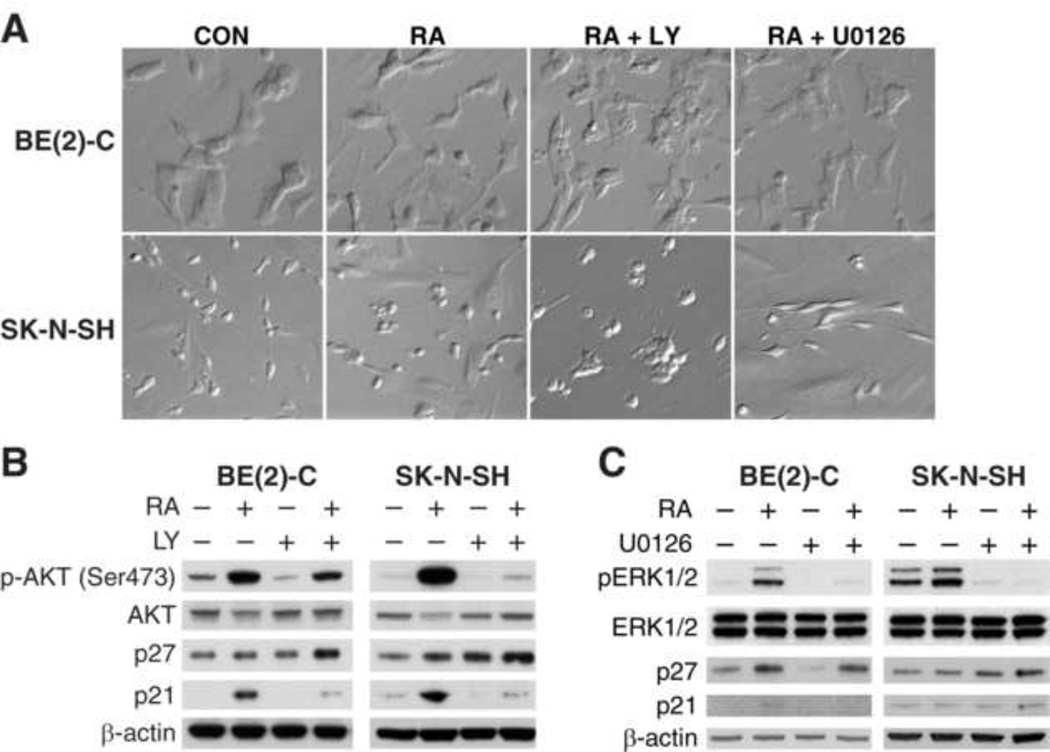

PI3K regulated RA-induced neuroblastoma cellular differentiation

To further validate the role of PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 on cell cycle proteins and RA-induced cellular differentiation, BE(2)-C and SK-N-SH cells were treated with RA along with PI3K and ERK inhibitors for 48 h. We found that RA-induced neuroblastoma cellular differentiation was completely blocked by PI3K inhibitor, LY294002, but not with ERK inhibitor, U0126, in both SK-N-SH and BE(2)-C cell lines (Fig. 4A). In addition, LY294002 treatment blocked RA-induced p-AKT (Ser473) and p21 expression in both cell lines (Fig. 4B). Conversely, p27Kip levels were slightly increased in both cell lines when treated with a combination of RA and LY compound. Treatment with U0126 did not alter the expression of p21 and p27kip in either cell line (Fig. 4C). Hence, our findings suggest that RA may affect p27Kip expression by a different mechanism such that it inhibits protein degradation [19], and that PI3K/AKT may be involved in degradation process [20]. We conclude that RA depends on PI3K to mediate cell differentiation, AKT activation, and p21 induction, while it does not appear that ERK1/2 activation is necessary for these functions.

Figure 4. PI3K regulated RA-induced neuroblastoma cellular differentiation.

(A) LY compound, a pharmacological inhibitor of PI3K, nearly completely prevented RA-induced cellular differentiation, whereas, U0126, a specific inhibitor of MEK1/2 failed to prevent RA (10 µM)-mediated differentiation in both BE(2)-C and SK-N-SH cells. (B) LY compound attenuated RA (10 µM)-induced increase in p-AKT and p21 protein levels; whereas p27Kip increased slightly in both BE(2)-C and SK-N-SH cells. (C) Inhibition of MEK1/2 using U0126 attenuated RA-induced increase in p-ERK1/2, but did not affect either p21 or p27Kip expressions in both BE(2)-C and SK-N-SH cells.

DISCUSSION

Neuroblastoma is a perplexing sympathetic chain-derived extra-cranial tumor that affects infants and children. In general, it is a highly aggressive cancer; however, those that are diagnosed in infancy have been known to spontaneously differentiate and even regress via unknown cellular processes. During past decades, investigators have determined that RA can play a critical role in the regulation of cancer progression. It has been shown that RA inhibits growth and induces apoptosis in cancers of prostate [21] and lung [22]. In patients with neuroblastoma, 13-cis RA has also shown some promising clinical efficacy [15,23]. However, the exact cellular mechanisms involved in RA-induced neuroblastoma cellular differentiation remain unclear.

RA initiates several intracellular signal transduction cascades [24] that are not well characterized but seem to contribute significantly to its therapeutic potential. A better understanding of molecular mechanisms involved may be important in the clinical application of RA. In the present study, our findings show that RA induced human neuroblastoma cellular differentiation and increased cell cycle arrest. Interestingly, RA resulted in attenuated apoptosis and promoted neuroblastoma cell survival under serum-starved condition, suggesting a potential dual mechanism of RA on neuroblastoma cellular growth and probable reasons for the limited clinical success of RA treatment in neuroblastoma patients. In addition, cell survival pathways like PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 pathways were activated by RA in SK-N-SH and BE(2)-C cell lines. We also found that both pathways regulated RA-induced RXR transcriptional activity in neuroblastoma cells. However, inhibition of PI3K pathway, but not MAPK, reversed RA-stimulated cellular differentiation. Collectively, these findings suggest that PI3K and ERK1/2 play crucial roles during RA-induced cellular differentiation and survival.

CDK inhibitors, p21 and p27Kip, are key cell cycle regulators in mammalian cells. They act by directly inhibiting cyclin/CDK complexes and hence regulating G1 to S phase transition, which is pivotal to fate of cellular proliferation, differentiation, and cell death [25]. In the present study, both p21 and p27Kip were upregulated by RA treatment in neuroblastoma cells. In particular, inhibiting PI3K/AKT appeared to downregulate p21, but not p27Kip. The cellular mechanism for induction of p21 is likely through nuclear RAR/RXR binding to the RXRE site of the p21 promoter. The significance of discordant regulation of p21 and p27Kip by PI3K after RA is unclear and is beyond the scope of this study. However, it is hypothesized that upregulation of p27Kip by RA slows down its degradation process [26]. In our study, p27Kip accumulated upon inhibition of PI3K/AKT. Similarly, in breast carcinoma cells, knockdown of PI3K by siRNA increased p27Kip accumulation [27]. The activity of p27Kip is controlled by its distribution among the different cell compartments nucleus and cytoplasm [28]. We speculate that blocking PI3K activates AKT downstream target, FoxO, which is a transcription factor described to upregulate p27Kip at the transcriptional level. AKT can directly phosphorylate p27Kip at T157, thereby promoting its translocation to the cytoplasm where it is then inactivated [29,30] and stabilized in a phosphorylation-independent manner by the PI3K pathway [31].

In conclusion, findings from this study demonstrate that RA induces human neuroblastoma cell differentiation by arresting cell cycle progression at the G0/G1 phase, and upregulating the CDK inhibitors p21 and p27Kip1. Moreover, RA activated both AKT and ERK1/2 in neuroblastoma cells; however, the PI3K/AKT pathway is more critically involved in RA-induced cellular differentiation and is upstream of RA nuclear receptors RAR/RXR in neuroblastoma cells. Our study has further discerned molecular mechanisms involved in RA-induced neuroblastoma cellular differentiation, and this may shed some valuable insights to better understanding and applications of RA in the treatment of patients with highly aggressive neuroblastoma.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Retinoic acid (RA) induces neuroblastoma cells differentiation, which is accompanied by G0/G1 cell cycle arrest.

RA resulted in neuroblastoma cell survival and inhibition of DNA fragmentation; this is regulated by PI3K pathway.

RA activates PI3K and ERK1/2 pathway; PI3K pathway mediates RA-induced neuroblastoma cell differentiation.

Upregulation of p21 is necessary for RA-induced neuroblastoma cell differentiation

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Karen Martin for assistance with the manuscript preparation. This work was supported by a grant R01 DK61470 from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- ERK

extracellular-signal-regulated kinase

- RA

retinoic acid

- RARs

all-trans-RA (ATRA) receptor

- RXRs

retinoid X (9-cis-RA) receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Duester G. Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis. Cell. 2008;134:921–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noy N. Between death and survival: retinoic acid in regulation of apoptosis. Annu Rev Nutr. 2010;30:201–217. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagpal S. Retinoids: inducers of tumor/growth suppressors. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:xx–xxi. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma Y, Koza-Taylor PH, DiMattia DA, Hames L, Fu H, Dragnev KH, Turi T, Beebe JS, Freemantle SJ, Dmitrovsky E. Microarray analysis uncovers retinoid targets in human bronchial epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:4924–4932. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keedwell RG, Zhao Y, Hammond LA, Qin S, Tsang KY, Reitmair A, Molina Y, Okawa Y, Atangan LI, Shurland DL, Wen K, Wallace DM, Bird R, Chandraratna RA, Brown G. A retinoid-related molecule that does not bind to classical retinoid receptors potently induces apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells through rapid caspase activation. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3302–3312. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reynolds CP, Wang Y, Melton LJ, Einhorn PA, Slamon DJ, Maurer BJ. Retinoic-acidresistant neuroblastoma cell lines show altered MYC regulation and high sensitivity to fenretinide. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2000;35:597–602. doi: 10.1002/1096-911x(20001201)35:6<597::aid-mpo23>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villablanca JG, Khan AA, Avramis VI, Seeger RC, Matthay KK, Ramsay NK, Reynolds CP. Phase I trial of 13-cis-retinoic acid in children with neuroblastoma following bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:894–901. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.4.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007;129:1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masia S, Alvarez S, de Lera AR, Barettino D. Rapid, nongenomic actions of retinoic acid on phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase signaling pathway mediated by the retinoic acid receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:2391–2402. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan J, Kao YL, Joshi S, Jeetendran S, Dipette D, Singh US. Activation of Rac1 by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in vivo: role in activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways and retinoic acid-induced neuronal differentiation of SH-SY5Y cells. J Neurochem. 2005;93:571–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodart JF. Extracellular-regulated kinase-mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade: unsolved issues. J Cell Biochem. 2010;109:850–857. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fulda S. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway as therapeutic target in neuroblastoma. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2009;9:729–737. doi: 10.2174/156800909789271521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holzel M, Huang S, Koster J, Ora I, Lakeman A, Caron H, Nijkamp W, Xie J, Callens T, Asgharzadeh S, Seeger RC, Messiaen L, Versteeg R, Bernards R. NF1 is a tumor suppressor in neuroblastoma that determines retinoic acid response and disease outcome. Cell. 2010;142:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caino MC, Meshki J, Kazanietz MG. Hallmarks for senescence in carcinogenesis: novel signaling players. Apoptosis. 2009;14:392–408. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0316-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthay KK, Villablanca JG, Seeger RC, Stram DO, Harris RE, Ramsay NK, Swift P, Shimada H, Black CT, Brodeur GM, Gerbing RB, Reynolds CP. Treatment of high-risk neuroblastoma with intensive chemotherapy, radiotherapy, autologous bone marrow transplantation, and 13-cis-retinoic acid. Children's Cancer Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1165–1173. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang JH, Rychahou PG, Ishola TA, Qiao J, Evers BM, Chung DH. MYCN silencing 16 induces differentiation and apoptosis in human neuroblastoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang L, Mear JP, Kuan CY, Colbert MC. Retinoic acid induces CDK inhibitors and growth arrest specific (Gas) genes in neural crest cells. Dev Growth Differ. 2005;47:119–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2005.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coqueret O. New roles for p21 and p27 cell-cycle inhibitors: a function for each cell compartment? Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamura M, Matsuo T, Stauffer J, Neckers L, Thiele CJ. Retinoic acid decreases targeting of p27 for degradation via an N-myc-dependent decrease in p27 phosphorylation and an N-myc-independent decrease in Skp2. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:230–239. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andreu EJ, Lledo E, Poch E, Ivorra C, Albero MP, Martinez-Climent JA, Montiel- Duarte C, Rifon J, Perez-Calvo J, Arbona C, Prosper F, Perez-Roger I. BCR-ABL induces the expression of Skp2 through the PI3K pathway to promote p27Kip1 degradation and proliferation of chronic myelogenous leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3264–3272. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammond LA, Brown G, Keedwell RG, Durham J, Chandraratna RA. The prospects of retinoids in the treatment of prostate cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 2002;13:781–790. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200209000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu XP, Fanjul A, Picard N, Pfahl M, Rungta D, Nared-Hood K, Carter B, Piedrafita J, Tang S, Fabbrizio E, Pfahl M. Novel retinoid-related molecules as apoptosis inducers and effective inhibitors of human lung cancer cells in vivo. Nat Med. 1997;3:686–690. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armstrong JL, Redfern CP, Veal GJ. 13-cis retinoic acid and isomerisation in paediatric oncology--is changing shape the key to success? Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:1299–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gianni M, Kopf E, Bastien J, Oulad-Abdelghani M, Garattini E, Chambon P, Rochette-Egly C. Down-regulation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway is involved in retinoic acid-induced phosphorylation, degradation, and transcriptional activity of retinoic acid receptor gamma 2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24859–24862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200230200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1501–1512. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zancai P, Dal Col J, Piccinin S, Guidoboni M, Cariati R, Rizzo S, Boiocchi M, Maestro R, Dolcetti R. Retinoic acid stabilizes p27Kip1 in EBV-immortalized lymphoblastoid B cell lines through enhanced proteasome-dependent degradation of the p45Skp2 and Cks1 proteins. Oncogene. 2005;24:2483–2494. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reagan-Shaw S, Ahmad N. RNA interference-mediated depletion of phosphoinositide 3- kinase activates forkhead box class O transcription factors and induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1062–1069. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ekholm SV, Reed SI. Regulation of G(1) cyclin-dependent kinases in the mammalian cell cycle. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:676–684. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shin I, Yakes FM, Rojo F, Shin NY, Bakin AV, Baselga J, Arteaga CL. PKB/Akt mediates cell-cycle progression by phosphorylation of p27(Kip1) at threonine 157 and modulation of its cellular localization. Nat Med. 2002;8:1145–1152. doi: 10.1038/nm759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viglietto G, Motti ML, Bruni P, Melillo RM, D'Alessio A, Califano D, Vinci F, Chiappetta G, Tsichlis P, Bellacosa A, Fusco A, Santoro M. Cytoplasmic relocalization and inhibition of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27(Kip1) by PKB/Akt-mediated phosphorylation in breast cancer. Nat Med. 2002;8:1136–1144. doi: 10.1038/nm762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brandts CH, Bilanges B, Hare G, McCormick F, Stokoe D. Phosphorylation-independent stabilization of p27kip1 by the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in glioblastoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2012–2019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408348200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]