Abstract

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) and heart failure (HF) are major causes of morbidity and mortality in the Western society. Advances in understanding the molecular pathology of these diseases, the evolution of vector technology, as well as defining the targets for therapeutic interventions has placed these conditions within the reach of gene-based therapy. One of the cornerstones of limiting the effectiveness of gene therapy is the establishment of clinically relevant methods of genetic transfer. Recently there have been advances in direct and transvascular gene delivery methods with the use of new technologies. Current research efforts in IHD are focused primarily on the stimulation of angiogenesis, modify the coronary vascular environment and improve endothelial function with localized gene-eluting catheters and stents. In contrast to standard IHD treatments, gene therapy in HF primarily targets inhibition of apoptosis, reduction in adverse remodeling and increase in contractility through global cardiomyocyte transduction for maximal efficacy. This article will review a variety of gene-transfer strategies in models of coronary artery disease and HF and discuss the relative success of these strategies in improving the efficiency of vector-mediated cardiac gene delivery.

Keywords: cardiac gene therapy, methods of gene delivery, ischemic heart disease, heart failure

INTRODUCTION

Gene therapies have demonstrated great potential for treating cardiovascular diseases in diverse animal models. Some of these experimental therapies are currently undergoing clinical evaluation.1–3 Although this progress is exciting, the successful translation into clinical practice is hindered by the need for further improvements in the following key areas: vector platforms, delivery technology, documentation of clinical feasibility, and consistent safety and efficacy.1 Specifically, there is an increased interest in developing gene therapeutics for the treatment of coronary vascular disease. Given that in the United States most cases of heart failure (HF) are due to coronary vascular disease, the gene therapeutics of interest should include therapeutic angiogenesis in the ischemic myocardium, prevention of post-angioplasty and in-stent restenosis, post-coronary bypass graft failure, and correction of the molecular mechanisms of cardiac deterioration.2 Organ-targeted gene-delivery techniques are an essential component of gene therapy for cardiac diseases both to increase the cardiac specificity and to augment the dose delivered to the myocardium. Pioneering studies with cardiac gene therapy demonstrate the ability to express transgenes in the hearts of normal animals. More complex studies have advanced therapeutics to Phase III clinical studies.3 This course (from bench to bedside) required more than two decades of research. The development of an appropriate vector and the design of the gene construct in murine and rodent species were the early focus of these efforts. Subsequently, critical problems with insufficient gene transfer were observed in early large animal studies. Thus it was evident that there was a significant gap in gene-delivery technology that—if not addressed—would be rate limiting for the advancement of the validated gene therapeutics.4 To date, considering the entire universe of gene therapeutics, there is not a single gene therapy product that has been FDA-approved for clinical use in the United States. The majority of cardiac gene therapy clinical trials have reported largely negative results in terms of efficacy. It is believed that the disparity between the pre-clinical and clinical results is directly attributable to the very low to undetectable levels of therapeutic expression in myocytes. Therefore, achieving sufficient gene transfer ischemic heart disease (IHD) with a reliable and safe delivery method has been a major therapeutic obstacle that must be addressed. Certainly for HF gene therapy, a paracrine effect notwithstanding the predominant mechanism of action is therapeutic myocyte gene expression. Unfortunately, the inability to transfer the genome copies into a substantial percentage of cells diminishes any chance of achieving therapeutic efficacy.5,6 The conditions required for efficacious vector-mediated gene delivery, including both the selection of the route of vector administration and the dosing strategy, need to be optimized using quantitative methods derived from pharmacokinetic analysis.7,8

There are many published methods to transduce myocardium. All existing techniques of gene transfer can be classified by the site of injection, interventional approach and variations of cardiac circulation.9 This article provides an overview of the most recent advancements in the development of cardiac gene-delivery technologies for ischemic heart disease (IHD) and HF. Emphasis is placed on the key clinical and technical parameters that continue to drive the demand for improving existing systems.

STRATEGIES FOR GENETIC MANIPULATION OF THE CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

The primary goal of cardiac gene therapy is to restore and/or knock out the expression of a gene. This is required to correct an inherited or acquired defect that has been strongly correlated with disease prevalence. The most common gene-therapy strategy for coronary vascular disease involves the exogenous overexpression of engineered cDNA encoding a gene of interest. The fundamental aim here is to increase the activity of a gene whose endogenous function linked with a disease-specific phenotype has been disrupted.10,11 In this case, cDNA encoding the deficient gene is delivered to the nuclei of myocytes via a viral or non-viral vector, then the gene-directed product is expressed and interacts with a defined target mechanism. Such strategies have been implemented with a variety of genes. These strategies include proangiogenic and cytoprotective factors in animal models, as well as in patients with vascular or myocardial diseases. An alternative strategy involves the acute blockade of gene transcription, thus limiting or negating subsequent translation with short single-stranded antisense oligodeoxynucleotides, decoy oligodeoxynucleotides, and ribozymes. Despite the advancement of numerous and diverse therapeutic approaches at the target level, inefficient delivery to the targets remains the outstanding problem. A viable cardiac gene-therapy platform (including both the therapeutic itself and the delivery system) must have the following attributes: the ability (i) to transfer the therapeutic gene to the ischemic, peri-ischemic or nonischemic regions; (ii) allow for successful transduction of the targeted percentage of myocytes and the appropriate level of gene transfer (for example, copy-number amount) within the transfected cardiomyocytes; (iii) establish a predictable relationship between genome-copy transfer and the level of improvement in contractility; and (iv) determine whether regional gene expression is sufficient to treat IHD or whether a global distribution is required.

MYOCARDIAL GENE-DELIVERY TECHNIQUES

Ischemic heart disease

Percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary artery bypass grafting are common treatments for patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) requiring revascularization. Despite the introduction of advanced novel drug-eluting stents and other device combination products, the failure rate of these procedures as a result of restenosis remains relatively high. It is estimated that over 30% of the patients with ischemic CAD cannot undergo coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention owing to suboptimal anatomy or the inability to perform complete revascularization.6 CAD is a generalized disease and patients who would be candidates for therapeutic neovascularization present with other comorbidities such as hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, hypertension, smoking and dietary problems. Independent of these comorbidities, however, the primary manifestations need to be treated. These are typically local lesions such as atherosclerotic stenotic plaques, acute or chronic thrombosis with vascular occlusions, vessel restenosis and neointimal hyperplasia. As the CAD course consists of both local and systemic origin, it is necessary to treat it with a combined approach (that is, local lesions and globally) with various drugs and/or gene products. In general, gene therapy in IHD and HF has a common purpose, which consists of correcting the basic molecular mechanisms in coronary vessels and myocardium to reverse cardiac damage. The methods of gene delivery are almost similar, except for the widely used intracoronary wall delivery in CAD. Nevertheless, it is necessary to note that in CAD (with no HF) the primary goals are: (i) prevention of the vessel’s restenosis and graft atherosclerosis; (ii) inhibition of proliferation of the vessel’s medial smooth muscle; (iii) targeting vascular cells by stabilizing coronary plaques; and (iv) inducing a therapeutic angiogenesis. During treatment of heart failure, the main effort should be directed to preventing or reducing cardiac remodeling (that is, inhibition of apoptosis, increasing the contractile function of failing myocytes, targeting electrophysiological abnormalities).

Direct intramyocardial delivery

Most investigators believe that there is an advantage of direct intramyocardial injection (Figures 1a–c) of angiogenic growth factors or genes over the intracoronary delivery method. The direct approach is the desired method for regional myocardial ischemia and focal arrhythmia therapy. Myocardial injection has been attempted successfully with an Ad/VEGF121 transgene in a pig infarction model. Both myocardial perfusion and wall thickening, as assessed by SPECT imaging, were improved 4 weeks after gene transfer.12 Another study featured a porcine model of chronic myocardial ischemia. It was demonstrated that intramyocardial delivery of Ad/VEGF-C improved 99mTc SPECT perfusion scan and collateral formation at the site of transfer.13 In a rat coronary-artery ligation model, the injection of human VEGF165 cDNA in the border zone of myocardial infarction (MI) induced angiogenesis.14 In a similar ovine study, sheep received 10 intramyocardial injections of a plasmid encoding VEGF165 in the border zone. It was shown that fractional shortening and wall thickening improved in this area as compared with controls.15 Further studies in the ischemic model (circumflex artery (Cx) artery occlusion) in rabbits revealed that treatment with VEGF165 resulted in significant improvements in fractional shortening and ejection fraction.16 Echo-guided transthoracic needle intramyocardial delivery of AAV encoding VEGF165 enhanced arteriogenesis and cardiomyocyte viability.17 At the same time, the study of Grossman et al.18 demonstrated that a lesser number of neutron-activated microspheres was retained after endomyocardial injections compared with postmortem controls (43% vs 89%). These authors suggest that a substantial proportion of injected material immediately exists in the myocardium after intramuscular delivery.

Figure 1.

Direct and transvascular techniques of gene delivery. (a) Intramyocardial injection via the intracavitary catheter in right ventricle. (b) Intramyocardial injection via the intracavitary catheter in left ventricle. (c) Intramyocardial injection via the syringe. (d) Transvascular intracavitary delivery. (e) Transvascular nonselective intracoronary delivery with aortic cross-clamping. (f) Transvascular selective antegrade intracoronary delivery.

Briefly summarizing these results, the direct-injection method offers a readily applicable delivery route to produce a highly localized expression of transgenes; however, transduction is restricted to the area surrounding the site of injection. Another significant limitation is that acute inflammatory responses due to injury tend to develop at the injection sites. These subsequently limit the therapy and enable an adaptive immune response against the vector and/or transgene products. Despite these disadvantages, many authors believe that this method is essential in optimizing angiogenesis approaches, as accurate mapping systems can selectively target areas of desired vessel formation.5,19

Intrapericardial delivery

This mode of administration offers the advantage of prolonged exposure of the administered gene across a wider area of the targeted surface. This is directly attributed to the reservoir function of the pericardium in retaining the vector post injection. In one study featuring ameroid occlusion of the Cx artery of dogs, Ad/VEGF165 was delivered with this method 10 days after MI. Pericardial expression was found in 2 weeks; however, collateral perfusion did not improve and there was no detectable increase in serum VEGF levels.20 The application of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) in a rabbit model of chronic myocardial ischemia demonstrated enhanced new epicardial small vessel growth.21 It was also found that the vascular number was larger in the subepicardial compared with the subendocardial infarcted areas.13 Although animal studies have supported the feasibility and safety of the intrapericardial delivery approach, such a delivery mode would not be suitable for patients with adhesions after multiple procedures.22

Peripheral-vein gene delivery

Intravenous bolus injection of bFGF has been ineffective in inducing an angiogenic response in a canine model of myocardial ischemia.23 This is likely due to first-pass uptake by low-affinity receptors in the lungs resulting in decreased bioavailability for myocardial uptake as a result of the intravenous infusion.24

Intracavitary gene delivery

Systemic administration of bFGF into the left atrium (Figure 1d) in a canine Cx artery occlusion model enhanced the collateral circulation by 21% within a period of 7–14 days post therapy. The regression of collateral development was not noted after withdrawal of treatment.25

Transvascular intracoronary wall delivery

Localized gene therapy is typically achieved with minimally invasive techniques, which feature endovascular interventions and multiple surgical options. However, vector-mediated gene transfer to the coronary vasculature with these approaches may be limited due to the following anatomical barriers: tunica adventitia, external and internal elastic lamina, smooth muscle cells and tunica intima within the endothelium (Figure 2). The adventitia is an active participant in remodeling and neointimal hyperplasia.26 The adventitial gene-transfer technique prevents blood-flow interruption, endothelium disruption and also vector leakage into the systemic circulation.27 Vector delivery in large peripheral arteries can be performed by direct injection into the adventitia during surgery. Biodegradable adventitial collars, gels or aerosolization devices represent the latest approaches in optimizing transfer.2

Figure 2.

Different catheters and stent for transvascular intracoronary wall gene delivery.

The ability to inhibit the proliferation of medial smooth muscle using gene therapy provides the unique opportunity to promote arterial resistance against atherosclerosis and neointimal hyperplasia.28 A high infusion pressure is required to disrupt the internal elastic membrane in order to effectively transduce smooth muscle cells, which are less accessible from the luminal side.2 A clinically applicable delivery device must meet the following requirements: (i) provide isolation and exposition of a vascular segment; (ii) maximize diffusion through the endothelium and basement membranes; (iii) result in high-efficiency penetration of the vascular wall while at the same time minimizing escape into the systemic circulation and perivascular space; (iv) minimize or eliminate the risk of vessel dissection or perforation; (v) permit downstream blood flow.29 To address these requirements, several types of balloon catheters for percutaneous gene delivery were developed.2,30,31 Double-balloon catheters (Figure 2a) were the first used for vascular gene therapy. This device includes two inflatable balloons separated by an intermediate space, into which the gene therapeutics can be infused through a separate lumen. After infusion, the vector remains in contact with the vessel wall between the proximal and distal occluding balloon. The solution can be withdrawn as required. Goldman et al.32 studied the effects of distending pressures on the permeability of dog and human arteries after the administration of horseradish peroxidase. Full penetration of the dog’s artery media was achieved by the application of 300 mm Hg pressure for 45 s. Another group evaluated gene delivery after adenoviralmediated transfer of a β-galactosidase marker gene into the sheep artery for a 30-min period. Three days later, gene expression was identified in ~30% of the luminal endothelial cells within the targeted area.33 The major disadvantage of these catheters is the requirement for occlusion of vessels for significant periods of time. This in turn increases the risk of ischemia and infarction.

Other catheters have also been used, which feature porous balloons through which the therapeutic is infused under high pressure into the lumen of a single balloon that contains multiple microscopic perforations (Figure 2b). Upon injection, the vector solution expands the balloon and exits through the pores, and subsequently enters the vessel wall. In a proof-of-concept study featuring this catheter, the successful delivery of heparin to the canine arterial wall was demonstrated.34 The perforated balloon catheter was also tested with the injection of a retroviral vector containing β-galactosidase into the rabbit aorta. The authors concluded that the practical use of this catheter is limited by the small number of cells that are actually transduced.35 Besides this striking disadvantage, another more severe consequence is the risk for intimal hemorrhage and distortion of media.36

Other variants of this catheter type that have been used for gene-therapy applications include hydrogels, where the vector is incorporated into a gel secured onto the surface of the catheter. The important feature, as in others presented, is that they maintain vascular flow during vector delivery. This catheter has been used with plasmid DNA encoding several VEGF isoforms. The results have shown that arterial application of this catheter with angiogenic cytokines achieves stimulation of collateral flow,37 inhibition of neointimal thickening and the restoration of endothelium-dependent vasomotor reactivity.38 The next-generation design of this catheter type, which is named Dispatch (Figure 2c), allows for the capability to save distal blood flow through a central lumen via infusion of a transgene between the artery wall and catheter. Despite exceptional design, long incubation times are required to achieve effective transduction. Furthermore, the overall transduction efficiency has been reported at very low levels (4.8%).39 The primary advantage of this catheter is the extended incubation time, as it can be inflated in the coronary arteries for a longer period of time, in fact approximately 16 h without inducing myocardial ischemia.40 Several authors claim that this catheter allows for greater transduction of an adenoviral vector in the endothelial cells (16%) versus smooth muscle cells (0.7%).41

Unique to the infiltrator catheters (Figure 2d) is the attempt to enhance transfer by injecting the vector into the vessel wall via micro injection needles. This method decreases the chances of systemic spread of the vector while also enhancing its transfer. It consists of three longitudinal polyurethane pads attached to the balloon with three linear arrays of micro needles positioned on the pads. The needle injection facilitates transgene delivery to the media and the adventitia.42 None of these devices is ideal, but several of them have been shown to increase the level of transfer across the coronary arteries. The Dispatch catheter permits a 10-min exposure to DNA–liposome complexes of the coronary arteries for patients immediately before stent placement.43

Despite these successes, however, the authors have now preferred the use of eluting stents (Figure 2e) over these catheters. The eluting stents represent a promising platform for localized delivery to the vascular wall due to their following advantages: extensive clinical experience in coronary catheterization procedures, safety, permanent scaffold structure and acting as reservoirs for viral vectors without systemic side effects.30,31,44,45 The stent coating is the main functional element, as its role is to provide a barrier between the metallic surface and the blood. Many animal studies have incorporated the use of polymers as stent coatings. Gene delivery from stents has been achieved using cellular techniques.46 Takahashi et al.,47 in order to alter the vector binding/release kinetics, used a polyurethane emulsion containing plasmid DNA that was implanted in rabbit arteries. The resulting plasmid gene transfer was not confined to the vessel wall at the site of stent implantation, but also appeared in other segments and collateral organs. Sharif et al., in the rabbit model, tested the hypothesis that phosphorylcholine stents can be used with adenovirus or AAV2. They demonstrated prolonged expression up to 28 days in neointimal smooth muscle cells.45 GFP-mediated plasmid DNA within polyactic-polyglycolic stents was efficiently expressed in cell cultures of the rat aortic smooth muscle cells (7.9% versus 0.6% in control).48 Application of bisphosphonate stents led to extensive localized Ad/GFP expression in the rat arterial wall. Adenovirus-inducible nitric oxide synthase attached to this stent resulted in inhibition of restenosis.49 Alternatively, Klugherz et al.50 hypothesized that site-specific delivery of adenoviral gene vectors from a stent could be achieved through a mechanism involving anti-viral antibody tethering. These antibodies enable the tethering of replication-defective adenoviruses through specific antigen–antibody affinity. It was shown that in pigs coronary arterial wall transduction was 5.9% after 7 days of stent deployment; however, neointimal transduction was more than 17%. Perstein et al. investigated a denatured collagen in DNA-stent coatings. Pig coronary studies performed with coated stents demonstrated 10.8% transduced plasmid DNA/GFP inside neointimal cells compared with the control group.51 Drug-eluting stents have been extensively used to prevent coronary restenosis in several human clinical trials.52

Transvascular intracoronary antegrade delivery

It is assumed that intracoronary selective and/or nonselective infusion (Figures 1e and f) provides better vascular access to all cardiac structures in comparison with other delivery methods. Lopez et al.53 experimented with a local intracoronary delivery system, which compared intracoronary bolus infusion and epicardial implantation of an osmotic polymer pump. The study incorporated the use of an ameroid occluder on the porcine Cx. After three VEGF165 administrations by local, intracoronary or extravascular delivery, there was an improvement in the coronary flow in the Cx territory at 3 weeks. They did not observe any differences in efficacy between the three forms of gene delivery. Single intracoronary bolus injection of VEGF165 is capable of significantly augmenting collateral flow to the chronic ischemic myocardium. Animals developed severe prolonged hypotension and exhibited a 50% mortality rate.54 Also, it was reported in a rat model that VEGF caused a dose-dependent reduction in cardiac output with an increase in vascular permeability and vasodilatation.55 Intracoronary injection of adenovirus encoding human fibroblast growth factor 5 resulted in the improvement in regional myocardial function. The evidence suggested that angiogenesis was achieved in an ameroid constrictor-induced ischemia in the pig model.56 In another study targeting angiogenesis, rabbits received intracoronary delivery of Ad/βARKct during aortic cross-clamping for 45 s. After 4 days, an infarction was created by acute occlusion of the Cx artery. βARKct expression with this delivery method improved contractility (LV dP/dtmax) and relaxation (LV dP/dtmin) and decreased end-diastolic pressure compared with control hearts.57 Direct intracoronary injection of bFGF to infarcted pig myocardium after embolization enhances the number of microvessels in viable and non-viable tissues.58 In a sheep model with apical MI and mitral regurgitation, percutaneous intracoronary delivery of AAV6/SERCA2a inhibited ventricular remodeling and activated anti-apoptotic pathways.59

Antegrade intracoronary delivery of therapeutic genes is the preferred route for ischemic myocardium; however, the coronary endothelium and additional barriers imposed by the basement membrane restrict transport. This subsequently limits the uptake and subsequent expression. Furthermore, when using this method, one must consider the very short (8–10 s) coronary transit time, the presence of coronary occlusions, the position of coronary catheters to minimize reflux of the delivered agent, anatomical variations and the increased risk of intracoronary dissection.60 Rajanayagam et al.,61 in the dog model with chronic myocardial ischemia, compared four regimes of bFGF injection: central venous bolus; peripheral intravenous; pericardial instillation; and intracoronary injection. Maximal collateral perfusion (an increase of >30%) was demonstrated in dogs that received long-term intracoronary infusion of bFGF. Administration of bFGF by other routes of injection and in dogs with single intracoronary dose failed to enhance collateral coronary perfusion.

Transvascular retrograde intracoronary sinus delivery

Selective pressure regulated retroinfusion via coronary sinus of FGF2 in a pig model of chronic myocardial ischemia enhanced collateral perfusion compared with antegrade delivery.62 In addition, various studies have shown that coronary-vein retroinfusion of VEGF165 and NFκB decoy oligonucleotide results in a reduction of myocardial reperfusion injury, postischemic inflammation and infarct size.63,64

Heart failure

Several genetic modulations are used to treat the underlying pathophysiological processes in heart failure. These include protecting the myocardium by increasing antioxidant gene expression, rescuing failing myocytes by enhancing proangiogenic factors and restoring contractile function.65 Strong evidence suggests that effective therapy for HF requires a gene delivery method capable of globally transducing the myocardium, a potent multiple-target approach that will work on different cardiac cells and signaling pathways,66 and one focused on the specific etiology.67

Direct intramyocardial delivery

Ten pigs underwent intramyocardial injections of Ad/VEGF121 in the LV territory. After 1 week they were paced for 7 days to induce HF. The authors analyzed fractional wall thickening and segmental shortening. The results demonstrated preservation of cardiac performance and recovery after gene transfer.68 Rengo et al.69 delivered AAV6/βARKct in HF rats after cryoinfarction. Twelve weeks later, rats demonstrated long-term transgene expression, improved contractility, reversal in LV remodeling and normalization of the neurohormonal status.

Transvascular intracoronary antegrade and retrograde delivery

Percutaneous catheter-based intracoronary delivery is one of the most attractive methods. The benefits of this technique include minimal invasiveness and a possibility of gene transfer to the desired area. High-pressure gene delivery,70,71 increasing gene administration up to 10min72 and increasing the flow rate of infusion73 are approaches that have been proposed to improve transduction efficiency. Iwanaga et al.74 delivered AAV/S16EPLN (phosholamban) in rats with severe HF 5 weeks post MI (ejection fraction ~20%). The method also included moderate hypothermia, and cardioplegic arrest with aortic and pulmonary artery cross-clamping. After 6 months, they reported a decrease in left ventricular end diastolic pressure to 3.2mmHg (control 13.4mmHg) and a significant increase in dP/dt max and dP/dt min.74 In a volume-overload HF pig study with intracoronary delivery of AAV1/SERCA2a, there was an increase of ejection fraction and +dP/dt. More importantly, in this study, there was a decrease in LV internal diastolic and systolic diameter.72 Nonselective intracoronary administration of Ad/SERCA2a through the catheter in the LV resulted in significant improvements in +dP/dt, −dP/dt and left ventricular end diastolic pressure.75 The same technique showed better survival in rats with HF (63% vs 9% in control) and an improved phosphocreatine/ATP ratio.76 The delivery of adenyl cyclase into coronary arteries (Ad/AC6) in a porcine pacing-induced HF model resulted in an improvement in LV function after treatment.77 Studies conducted with the delivery of the same gene after cross-clamping of the aorta and pulmonary artery during hypothermia led to an improvement in both systolic and diastolic LV function.78 In another study, transgenic rabbits with ischemic HF received Ad/βARKct by selective intracoronary injection. The authors noted improvement in LV systolic performance.79 The technique included an adenosine-arrested heart, aortic cross-clamping and injection of Ad/βARKct into the LV apex with the aim to attenuate development of HF after transmural MI.80 Pleger et al.81 injected AAV6/S100A1 into the aortic root in a rat model of cryoinfarction. The animal was cooled to 29 °C and the aorta was clamped for 2 min. Functional myocardial recovery was evidenced by a reduction in LV chamber dilatation and cardiac hypertrophy. Two weeks post MI, a lentiviral vector containing the SERCA2 gene was infused into a rat arrested heart during hypothermia along with occlusion of aorta and pulmonary artery. Six months after gene transfer the results indicated SERCA2a expression protected against LV dilatation, and, more importantly, reduced mortality rates.82 Simultaneous antegrade (LAD artery) and retrograde (great cardiac vein) administration of Ad/KCNH2 to the infarct border zone eliminated ventricular arrhythmias in a porcine model.83 Myocardial gene transfer of AAV9/S100A1 in ischemic HF pigs was achieved by a selective retroinfusion catheter in the anterior cardiac vein during LAD artery occlusion. Results showed significant improvement in both systolic and diastolic LV performance compared with HF control groups.84

Table 1a and b summarizes the benefits and limitations of the above-mentioned strategies.

Table 1.

Available methods of cardiac gene delivery

| Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|

| (a) Direct gene delivery methods | |

| Simple and reproducible results | Transgene expression is limited to injection site(s) |

| Readily applicable for therapeutic angiogenesis or focal anti-arrhythmic therapies | Pervasive problem with exposure to systemic bloodstream |

| Superiority in targeting global phenotypic changes such as improved contractility and altering ECG intervals | Homogeneous expression is not achieved |

| Allows for specific anatomical targeting via delivery of higher concentration of therapeutics at designated areas | Administration issues associated with acute inflammatory response secondary to myocardial injury |

| Avoids the complications of transfer across the endothelial barrier | Higher incidence of adaptive mediated immune responses |

| Little concern with the effect of neutralizing antibodies | |

| (b) Transvascular gene delivery methods | |

| Ability to modify the system setup to enhance gene expression | Single-pass kinetics with intracoronary deliverya |

| Allows for global myocardial distribution of vector | High incidence of collateral organ exposurea |

| Minimally invasive and readily used in clinical practice | Does not perform well in atherosclerotic vessels |

| Promotes a homogeneous gene expression profile | These delivery methods expose the vector to neutralizing antibodies |

| Ability to have repeat administrations over time | Higher incidence of T cell-mediated immune response against vector and or transgene products |

| Highest gene transfer potential achieved with true closed-loop cardiac systemsa | Multiple cross-clamping and/or occlusion techniques not clinically feasible Closed recirculation systems featuring cardiopulmonary bypass and/or selective pressure-regulated procedures are expensive and difficult to implement |

Excludes closed-loop recirculation delivery systems (e.g. MCARD).

An ideal animal genetic model is threefold. It should mimic human disease, be easy to reproduce and be suitable for assessment of heart function. Newer technological advances in nuclear cardiology and ultrahigh-resolution ultrasound, micromodifications of conductance and Millar catheters, as well as creation of recombinant viral vectors have removed the barrier in research studies between small and large animal models. However, it should be noted that despite the enhancements in technology, contradictory results remain between rodent and human studies with endothelin receptor antagonists and GFP-related cardiomyopathy.85 Moreover, a significant difference exists in genetic background, rate of metabolism, neurohormonal activation and basic cardiac physiology (that is, myosin heavy chain isoforms, quantitative balance of Ca2+ flux and so on) Consequently, this proves that large animals are potentially better-suited gene therapy candidates for preclinical evaluation.67

OPTIMIZATION OF GENE-DELIVERY TECHNOLOGIES

There are certain factors to consider when deciding which gene delivery technique is more efficient. Figure 3 lists the technological advances necessary for optimal gene delivery. The following is a description of the procedures currently utilized in cardiovascular research.

Figure 3.

Optimization of gene delivery technology.

Ischemic preconditioning

Several advanced techniques have been used to optimize percutaneous intracoronary catheter delivery and include transient myocardial ischemia with occlusion of various vessels, coronary venous blockade, and aortic and pulmonary artery cross-clamping and so on.74,75,78,80–82,84 Each of these modifications demonstrated an enhancement of gene transduction under brief episodes of ischemia. We will not discuss how these manipulations can be used in the clinical setting. It is clear that ischemic preconditioning shifts cardiac metabolism and promotes the release of a variety of substances such as adenosine, bradykinin and oxygen-derived free radicals into the extracellular fluid, thereby causing pharmacological preconditioning with increasing coronary endothelial permeability. The improvement in expression is concurrent with the increased risk of permanent infarction.86,87

Closed-loop recirculatory systems

Cardiopulmonary bypass-based methodology: The feasibility to create an isolated closed-loop system in the large animal model using cardiopulmonary bypass was developed by Bridges et al.88 This technique integrates a closed retrograde transcoronary sinus delivery system with the creation of a dual-perfusion circuitry, which is very efficient in isolating the cardiac circuit from the systemic circulation (Figure 4a).8 It was demonstrated that the scAAV6-mediated model using cardiopulmonary bypass delivery results in global, cardiac-specific LV gene expression compared with intramuscular injection.89

Catheter-based methodology: A percutaneous cardiac catheterization featuring a closed-loop configuration was developed. It consists of a catheter for coronary artery antegrade gene delivery with collection of the coronary venous effluent. It also includes a support device to prevent coronary sinus collapse (V-Focus)90 (Figure 4b). The authors used this system in pacing-induced HF in the sheep. Two weeks after delivery of adenovirus-expressing mutant phospholamban (AdS16E), it was demonstrated that LV ejection fraction had significantly improved (50% vs 27%). There were also reductions in LV filling pressures and end-diastolic diameter. The same group showed that there was an advantage of closed-loop recirculation in direct comparison with antegrade coronary delivery in affecting systolic and diastolic parameters of heart function after delivery of AAV2/1-mediated SERCA2a.91 However, analysis of the results indicated that usage of V-Focus did not achieve a ‘closed loop’ system; more than 99% of the injected vector leaked into the systemic circulation.92

Figure 4.

Closed-loop recirculatory systems. (a) Cardiopulmonary bypass-based technology e.g., molecular cardiac surgery with recirculating delivery (MCARD). After initiating systemic bypass, the vent cannulas were placed into left and right ventricles and connected to the venous limb of the circuit. The arterial limb is connected to the coronary sinus catheter. After stopping the heart with cardioplegia, recirculation commences for 20min and then coronary circuit flashed. (b) Catheter-based technology (V-Focus). Coronary venous blood was drained from the coronary sinus. Following oxygenation the blood is returned to the left main coronary artery via a roller pump. Gene of interest was delivered into the antegrade limb of the circuit. Time of recirculation is 10min. To minimize systemic expression coronary venous blood collection continued for 2 min, and the blood was diverted to a drainage bag. Main differences between V-Focus and MCARD: (i) beating vs stopping heart; (ii) direction of recirculation (coronary arteries to coronary sinus vs coronary sinus to coronary arteries); (iii) time of recirculation (10 vs 20min); (iv) percutaneous catheter- based methodology vs cardiopulmonary bypass-based.

Despite the criticism of these two methods,92–94 it should be noted that the creation of a true closed-loop recirculation is undoubtedly one of the most promising systems for gene transfer, providing very high expression levels in the most efficient manner. Moreover, they also provide a unique opportunity to limit systemic exposure, which increases the safety factor.

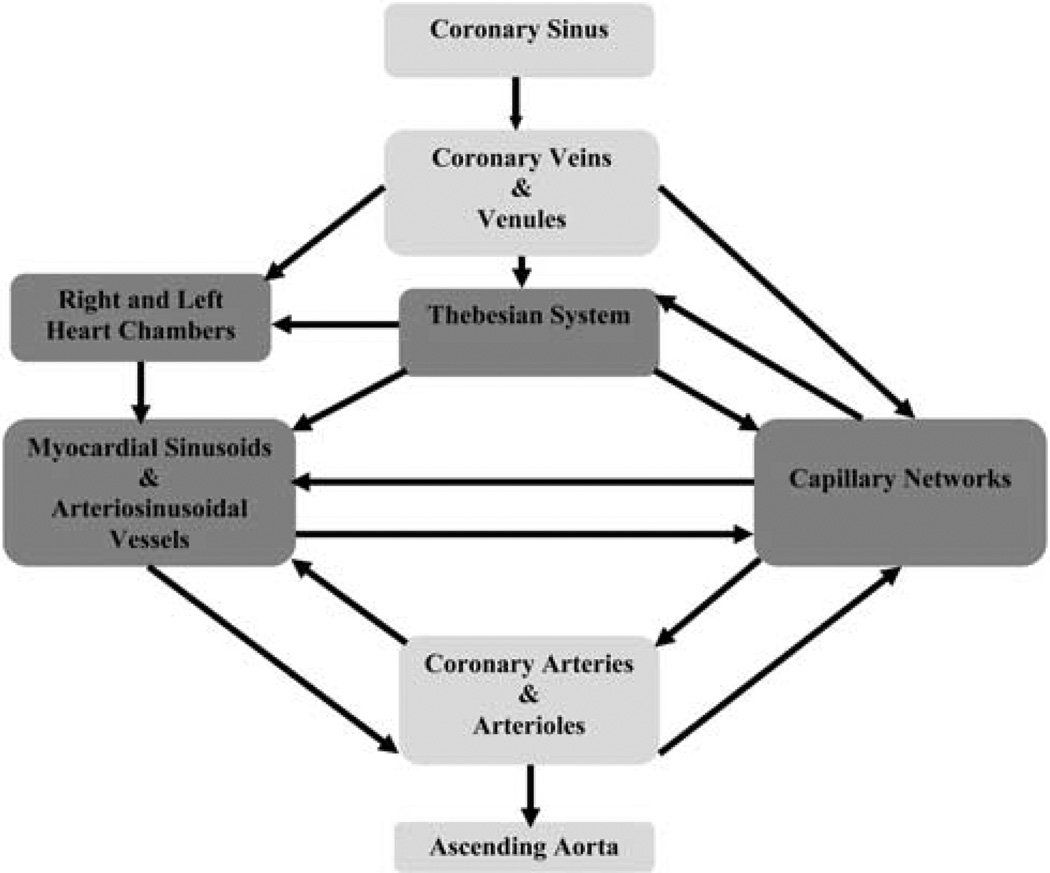

Retrograde infusion through the coronary sinus

Since Lillehei et al.95 successfully performed aortic-valve surgery with continuous retrograde coronary sinus perfusion to protect the heart, there has been much interest in retrograde techniques to administer various pharmacological drugs. Retrograde coronary infusion, compared with antegrade, provides a more uniform distribution of agents in the presence of CAD. To understand how retrograde gene delivery might facilitate efficient transduction, the interrelationship of the coronary venous and arterial anatomy must be considered. The coronary venous system connects with the capillaries mostly through the thebesian vessels (Figure 5). It is known that small molecular-weight substances including viral vectors can transverse the capillary endothelium by several different mechanisms. Retrograde delivery changes the pressure-driving forces (hydrostatic and/or osmotic) and increases capillary filtration pressure, thereby augmenting viral movement (Figure 6a). In addition, another advantage of this procedure is its ability to overcome the resistance of precapillary sphincters proximally located on the arterial side of the capillary beds. Thus, less blood is shunted through the thoroughfare channels into the cardiac chambers. (Figure 6b). A main limitation of retrograde injection, however, is the relatively poor perfusion of the right ventricle. Many authors argue that coronary venous infusion allows for prolonged adhesion time of the vector to the cardiac endothelium. This effect directly results in both an increase in endothelial permeability as well as a higher pressure gradient across the interstitial capillaries and venules. As a consequence, this promotes the transfer of macromolecular particles into the interstitium of the heart.62,63,96,97

Figure 5.

Schematic of pathways of retrograde gene delivery via coronary sinus.

Figure 6.

(a) The movement of fluid between capillaries and the interstitial fluid. The direction of fluid with vector movement across the capillary wall depends on the difference between two opposing forces: hydrostatic and osmotic pressure. With retrograde perfusion, hydrostatic pressure increases at the venous end of the capillaries and therefore gene filtration and transduction are also increased. (b) Coronary capillary net. After the tissue has been perfused through the coronary sinus, capillaries join to become arterioles and metarterioles which return blood to the aorta. A capillary net consist of two types of vessels: true capillaries which provide exchange between cells and thoroughfare (shunts) channels which directly connects the arterioles and venules. Precapillary sphincters are rings of smooth muscles at the origin of arterial capillaries that regulate blood flow through a tissue. The advantage of the retrograde delivery is its ability to overcome the resistance of precapillary sphincters proximally located on the arterial side of the capillary bed. Thus, less blood is shunted through the thoroughfare channels into the cardiac chambers.

Enhancement of transgene expression

Numerous methods have been proposed to enhance transgene expression. These methods can be either physical and/or pharmacological. These methods essentially increase the concentration gradient with modified infusion/perfusion pressure and flow,73,88,94,96–100 as well as increase the endothelial permeability via pharmacological agents.70,99

Minimizing collateral organ expression

Most recently, designing vectors that selectively target specific cell types are realized via the following strategies: modified cap sequences, increased affinity with cell-specific cased surface legends or the use of tissue-specific promoters. Many authors draw attention to adeno-associated viral vectors owing to their cardiac tropism and their ability to sustain long-term expression without integrating into the host genome.101,102

Currently, removing the residual virus from the circulation in order to minimize collateral expression is one of the most difficult challenges. After delivery, virus washout using various pumping devices now is the most utilized approach.88,91,103

CONCLUSION

Unfortunately, numerous cardiovascular gene therapy clinical trials have not demonstrated substantially positive results.3 This is partly due to the lack of safe, efficient and clinically reliable delivery methods. Most recently, several delivery approaches have been designed for the treatment of IHD and heart failure. A number of challenging obstacles must be resolved. Specifically, the creation of sophisticated minimally invasive surgical and catheter-based delivery systems that allow for: (i) precise localization of therapeutic agents; (ii) extended vector-contact time in the coronary circulation via closed-recirculation systems and (iii) minimization of collateral gene expression, which would potentially address the many limitations of existing systems.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Perry McCants for the excellent illustrations in this article. This work was supported by grants from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, NIH 1-R01-HL083078-01A2, and the Gene Therapy Resource Program of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, NIH P30-DK047757.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Melo LG, Pachori AS, Gnecchi M, Dzau VJ. Genetic therapies for cardiovascular diseases. Trends Mol Med. 2005;11:240–250. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quarck R, Holvoet P. Gene therapy approaches for cardiovascular diseases. Curr Gene Ther. 2004;4:207–223. doi: 10.2174/1566523043346499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hedman M, Hartikainen J, Ylä-Herttuala S. Progress and prospects: hurdles to cardiovascular gene therapy clinical trials. Gene Therapy. 2011;18:743–749. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ylä-Herttuala S, Markkanen JE, Rissanen TT. Gene therapy for ischemic cardiovascular diseases: some lessons learned from the first clinical trials. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004;14:295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karvinen H, Ylä-Herttuala S. New aspects in vascular gene therapy. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:208–211. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lassaletta AD, Chu LM, Sellke FW. Therapeutic neovascularization for coronary disease: current state and future prospects. Basic Res Cardiol. 2011;106:897–909. doi: 10.1007/s00395-011-0200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hajjar RJ, del Monte F, Matsui T, Rosenzweig A. Prospects for gene therapy for heart failure. Circ Res. 2000;86:616–621. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.6.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fargnoli AS, Katz MG, Yarnall C, Sumaroka MV, Stedman H, Rabinowitz JE, et al. A Pharmacokinetic analysis of molecular cardiac surgery with recirculation mediated delivery of BARKct gene therapy: developing a quantitative definition of the therapeutic window. J Cardiac Fail. 2011;17:691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz MG, Swain JD, Tomasulo CE, Sumaroka M, Fargnoli AS, Bridges CR. Current strategies for myocardial gene delivery. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:766–776. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinkel R, Trenkwalder T, Kupatt C. Gene therapy for ischemic heart disease. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2011;11:723–737. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2011.570749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melo LG, Pachori AS, Kong D, Gnecchi M, Wang K, Pratt RE, et al. Gene and cell-based therapies for heart disease. FASEB J. 2004;18:648–663. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1171rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mack CA, Patel SR, Schwarz EA, Zanzonico P, Hahn RT, Ilercil A. Biologic bypass with the use of adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of the complementary deoxyribonucleic acid for VEGF 121 improves myocardial perfusion and function in the ischemic porcine heart. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;115:168–177. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(98)70455-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pätilä T, Ikonen T, Rutanen J, Ahonen A, Lommi J, Lappalainen K, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor C-induced collateral formation in a model of myocardial ischemia. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwarz ER, Speakman MT, Patterson M, Hale SS, Isner JM, Kedes LH, et al. Evaluation of the effects of intramyocardial injection of DNA expressing vascular endothelial growth factor in a myocardial infarction model in the rat-angiogenesis and angioma formation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1323–1330. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00522-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vera Janavel GL, De Lorenzi A, Cortes C, Olea FD, Cabeza Meckert P, Bercovich A, et al. Effect of VEGF gene transfer on infarct size, left ventricular function and myocardial perfusion in sheep after two months of coronary artery occlusion. J Gene Med. 2011 doi: 10.1002/jgm.1608. e-pub ahead of print 26 September 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bull DA, Bailey SH, Rentz JJ, Zebrack JS, Lee M, Litwin SE, et al. Effect of Terplex/VEGF-165 gene therapy on left ventricular function and structure following myocardial infarction. J Control Release. 2003;93:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2003.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrarini M, Arsic N, Recchia FA, Zentilin L, Zacchigna S, Xu X, et al. Adeno-associated virus-mediated transduction of VEGF 165 improves cardiac tissue viability and functional recovery after permanent coronary occlusion in conscious dogs. Circ Res. 2006;98:954–961. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000217342.83731.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grossman PM, Han Z, Palasis M, Barry JJ, Lederman RJ. Incomplete retention after direct myocardial injection. Cathet Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;55:392–397. doi: 10.1002/ccd.10136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishikawa K, Tilemann L, Fish K, Hajjar RJ. Gene delivery methods in cardiac gene therapy. J Gene Med. 2011;13:566–572. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lazarous DF, Shou M, Stiber JA, Hodge E, Thirumurti V, Goncalves L, et al. Adenoviral-mediated gene transfer induces sustained pericardial VEGF expression in dogs: effect on myocardial angiogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;44:294–302. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landau C, Jacobs AK, Haudenschild CC. Intrapericardial basic fibroblast growth factor induces myocardial angiogenesis in a rabbit model of chronic ischemia. Am Heart J. 1995;129:924–931. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kornowski R, Fuchs S, Leon MB, et al. Delivery strategies to achieve therapeutic myocardial angiogenesis. Circulation. 2000;101:454–458. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.4.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thirumurti V, Shou M, Hodge E, Concalves L, Epstein SE, Lazarous DF, et al. Lack of efficacy of intravenous basic fibroblast growth factor in promoting myocardial angiogenesis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:54A. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazarous DF, Shou M, Stiber JA, Dadhania DM, Thirumurti V, Hodge E, et al. Pharmacodynamics of basic fibroblast growth factor: route of administration myocardial and systemic distribution. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;36:78–85. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazarous DF, Scheinowitz M, Shou M, Hodge E, Rajanayagam S, Hunsberger S, et al. Effects of chronic systemic administration of basic fibroblast growth factor on collateral development in the canine heart. Circulation. 1995;91:145–153. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott NA, Cipolla GD, Ross CE, Dunn B, Martin FH, Samuel JL, et al. Identification of a potential role for the adventitia in vascular lesion formation after balloon overstretch injury of porcine coronary arteries. Circulation. 1996;93:2178–2187. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.12.2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hiltunen MO, Turunen MP, Turunen AM, Rissanen TT, Laitinen M, Kosma VM, et al. Biodistribution of adenoviral vector to nontarget tissues after local in vivo gene transfer to arterial wall using intravascular and periadventitial gene delivery methods. FASEB J. 2000;14:2230–2236. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0145com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dzau VJ, Braun-Dullaeus RC, Sedding DG. Vascular proliferation and atherosclerosis: new perspectives and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med. 2002;8:1249–1256. doi: 10.1038/nm1102-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barath P, Popov A, Dillehay GL, Matos G, McKiernan T. Infiltrator angioplasty balloon catheter. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1997;41:333–341. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0304(199707)41:3<333::aid-ccd15>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaffney MM, Hynes SO, Barry F, O’Brien T. Cardiovascular gene therapy: current status and therapeutic potential. Brit J Pharm. 2007;152:175–188. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharif F, Daly K, Crowley J, O’Brien T. Current status of catheter- and stent-based gene therapy. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;64:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldman B, Blanke H, Wolinsky H. Influence of pressure on permeability of normal and diseased muscular arteries to horse-radish peroxide. A new catheter approach. Atherosclerosis. 1987;65:215–225. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(87)90037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rome JJ, Shayani V, Newmark KD, Farrell S, Lee SW, Virmani R, et al. Adenoviral vector mediated gene transfer into sheep arteries using a double balloon catheter. Hum Gene Ther. 1994;5:1249–1258. doi: 10.1089/hum.1994.5.10-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolinsky H, Thung SN. Use of a perforated balloon catheter to deliver concentrated heparin into the wall of the normal canine artery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:475–481. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flugelman MY, Jaklitsch MT, Newman KD, Casscells W, Bratthauer GL, Dichek DA. Low level in vivo gene transfer into the arterial wall through a perforated balloon catheter. Circulation. 1992;85:1110–1117. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.3.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Willard JE, Landau C, Glamann DB, Burns D, Jessen ME, Pirwitz MJ, et al. Genetic modification of the vessel wall. Circulation. 1994;89:2190–2197. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.5.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takeshita S, Tsurumi Y, Couffinahl T, Asahara T, Bauters C, Symes J, et al. Gene transfer of naked DNA encoding for three isoforms of VEGF stimulates collateral development in vivo. Lab Invest. 1996;75:487–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asahara T, Chen D, Tsurumi Y, Kearney M, Rossow S, Symes J, et al. Accelerated restitution of endothelial integrity and endothelium-dependent function after phVEGF165 gene transfer. Circulation. 1996;94:3291–3302. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.12.3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Numaduchi Y, Okumura K, Harada M, Naruse K, Yamada M, Osanai H, et al. Catheter-based prostacyclin synthase gene transfer prevents in-stent restenosis in rabbit atheromatous arteries. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clowes AW, Collazzo RE, Karnovsky MJ. A morphologic and permeability study of luminal smooth muscle cells after arterial injury in the rat. Lab Invest. 1978;39:141–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tahlil O, Brami M, Feldman LJ, Branellec D, Steg PG. The Dispatch catheter as a delivery tool for arterial tool for arterial gene transfer. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;33:181–187. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pavlides GS, Barath P, Maginas A, Vasilikos V, Cokkinos DV, O’Neill WW. Intramural drug delivery by direct injection within arterial wall: first clinical experience with a novel intracoronary delivery-infiltrator system. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1997;41:287–292. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0304(199707)41:3<287::aid-ccd9>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laitinen M, Hartikainen J, Hiltunen MO, Eranen J, Kiviniemi M, Narvanen O, et al. Catheter-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor gene transfer to human coronary arteries after angioplasty. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:263–270. doi: 10.1089/10430340050016003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fishbein I, Chorny M, Levy RJ. Site-specific gene therapy for cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2010;13:203–213. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharif F, Hynes SO, McMahon J, Cooney R, Conroy S, Dockery P, et al. Gene-eluting stents: comparison of adenoviral and adeno-associated viral gene delivery to the blood vessel wall in vivo. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:741–750. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koren B, Weisz A, Fisher L, Gluzman Z, Preis M, Avramovitch N, et al. Efficient transduction and seeding of human endothelial cells into metallic stents using bicistronic pseudo-typed retroviral vectors encoding vascular endothelial growth factor. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2006;7:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takahashi A, Palmer-Opolski M, Smith RC, Walsh K. Transgene delivery of plasmid DNA to smooth muscle cells and macrophages from a biostable polymer-coated stent. Gene Therapy. 2003;10:1471–1478. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klugherz BD, Jones PL, Cui X, Chen W, Meneveau NF, DeFelice S, et al. Gene delivery from a DNA controlled-release stent in porcine coronary arteries. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:1181–1184. doi: 10.1038/81176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fishbein I, Alferiev IS, Nyanguile O, Gaster R, Vohs JM, Wong GS, et al. Bisphosphonate-mediated gene vector delivery from the metal surfaces of stents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:159–164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502945102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klugherz BD, Song C, DeFelice S, Cui X, Lu Z, Connolly J, et al. Gene delivery to pig coronary arteries from stents carrying antibody-tethered adenovirus. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:443–454. doi: 10.1089/10430340252792576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perstein I, Connolly JM, Cui X, Song C, Li Q, Jones PL, et al. DNA delivery from an intravascular stent with a denatured collagen-polylactic-polyglycolic acid-controlled release coating: mechanisms of enhanced transfection. Gene Therapy. 2003;10:1420–1428. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lemos PA, Serruys PW, Sousa JE. Drug-eluting stents: cost versus clinical benefit. Circulation. 2003;107:3003–3007. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078025.19258.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lopez JJ, Laham RJ, Stamler A, Pearlman JD, Bunting S, Kaplan A, et al. VEGF administration in chronic myocardial ischemia in pigs. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;40:272–281. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hariawala MD, Horowitz JR, Esakof D, Sheriff DD, Walter DH, Keyt B, et al. VEGF improves myocardial blood flow but produces EDRF-mediated hypotension in porcine hearts. J Surg Res. 1996;63:77–82. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1996.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang R, Thomas GR, Bunting S, Ko A, Ferrara N, Keyt B, et al. Effects of vascular endothelial growth factor on hemodynamics and cardiac performance. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1996;27:838–844. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199606000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Giordano FJ, Ping P, McKirnan MD, Nozaki S, DeMaria AN, Dillmann WH, et al. Intracoronary gene transfer of fibroblast growth factor-5 increases blood flow and contractile function in an ischemic region of the heart. Nat Med. 1996;2:534–539. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tevaearai HT, Walton GB, Keys JR, Koch WJ, Eckhart AD. Acute ischemic cardiac dysfunction is attenuated via gene transfer of a peptide inhibitor of the beta-adrenergic receptor kinase (betaARK1) J Gene Med. 2005;7:1172–1177. doi: 10.1002/jgm.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Battler A, Scheinowitz M, Bor A, Hasdai D, Vered Z, Di Segni E, et al. Intracoronary injection of basic fibroblast growth factor enhances angiogenesis in infarcted swine myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:2001–2006. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90790-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beeri R, Chaput M, Cuerrero L, Kawase Y, Yosefy C, Abedat S, et al. Gene delivery of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase inhibits ventricular remodeling in ischemic mitral regurgitation. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:627–634. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.891184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mariani JA, Kaye DM. Delivery of gene and cellular therapies for heart disease. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2010;3:417–426. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rajanayagam MA, Shou M, Thirumurti V, Lazarous DF, Quyyumi AA, Goncalves L, et al. Intracoronary basic fibroblast growth factor enhances myocardial collateral perfusion in dogs. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:519–526. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00550-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.von Degenfeld G, Raake P, Kupatt C, Lebherz C, Hinkel R, Gildehaus FJ, et al. Selective pressure-regulated retroinfusion of FGF-2 into the coronary vein enhances regional myocardial blood flow and function in pigs with chronic myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1120–1128. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00915-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kupatt C, Wichels R, Deiss M, Molnar A, Lebherz C, Raake P, et al. Retroinfusion of NFkappaB decoy oligonucleotide extends cardioprotection achieved by CD18 inhibition in a preclinical study of myocardial ischemia and retroinfusion in pigs. Gene Therapy. 2002;9:518–526. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kupatt C, Hinkel R, Vachenauer R, Horstkotte J, Raake P, Sandler T, et al. VEGF165 transfection decreases postischemic NF-kappa B-dependent myocardial reperfusion injury in vivo: role of eNOS phosphorylation. FASEB J. 2003;17:705–707. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0673fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McPhee AWJ, Samulski RJ. Gene therapy for cardiomyocytes, a heart beat away. Gene Therapy. 2009;17:707–708. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vinge LE, Raake PW, Koch WJ. Gene therapy in heart failure. Circ Res. 2008;102:1458–1470. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.173195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Katz MG, Fargnoli AS, Tomasulo CE, Pritchette LA, Bridges CR. Model-specific selection of molecular targets for heart failure gene therapy. J Gene Med. 2011;13:573–586. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leotta E, Patejunas G, Murphy G, Szokol J, McGregor L, Carbray J, et al. Gene therapy with adenovirus-mediated myocardial transfer of VEGF 121 improves cardiac performance in a pacing model of congestive heart failure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;123:1101–1103. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.121044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rengo G, Lymperopoulos A, Zincarelli C, Donniacuo M, Soltys S, Rabinowitz JE, et al. Myocardial adeno-associated virus serotype 6-BARKct gene therapy improves cardiac function and normalizes the neurohormonal axis in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2009;119:89–98. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.803999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wright MJ, Wightman LML, Latchman DS, Marber MS. In vivo myocardial gene transfer:optimization and evaluation of intracoronary gene delivery in vivo. Gene Therapy. 2001;8:1833–1839. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hajjar RJ, Schmidt U, Matsui T, Guerreno JL, Lee K-H, Gwathmey JK, et al. Modulation of ventricular function through gene transfer in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5251–5256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kawase Y, Ly HQ, Prunier F, Lebeche D, Shi Y, Jin H, et al. Reversal of cardiac dysfunction after long-term expression of SERCA2a by gene transfer in a pre-clinical model of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1112–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Emani SM, Shah AS, Bowman MK, Emani S, Wilson K, Glower DD, et al. Catheter-based intracoronary myocardial adenoviral gene delivery: importance of intraluminal seal and infusion flow rate. Mol Ther. 2003;8:306–313. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Iwanaga Y, Hoshijima M, Gu Y, Iwatabe M, Dieterle T, Ikeda Y, et al. Chronic phospholamban inhibition prevents progressive cardiac dysfunction and pathological remodeling after infarction in rats. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:727–736. doi: 10.1172/JCI18716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Miyamoto MI, del Monte F, Schmidt U, DiSalvo TS, Kang ZB, Matsui T, et al. Adenoviral gene transfer of SERCA2a improves left-ventricular function in aortic-banded rats in transition to heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:793–798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.del Monte F, Williams E, Lebeche D, Schmidt U, Rosenzweig A, Gwathmey JK, et al. Improvement in survival and cardiac metabolism after gene transfer of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPase in a rat model of heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:1424–1429. doi: 10.1161/hc3601.095574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lai NC, Roth DM, Gao MH, Tang T, Dalton N, Lay YY, et al. Intracoronary adenovirus encoding adenylyl cyclase 6 increases left ventricular function in heart failure. Circulation. 2004;119:330–336. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136033.21777.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rebolledo B, Lai NC, Gao MH, Takahashi T, Roth DM, Baird SM, et al. Adenylyl cyclase gene transfer increased function of the failing heart. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:1043–1048. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shah AS, White DC, Emani S, Kypson AP, Lilly RE, Wilson K, et al. In vivo ventricular gene delivery of a beta-adrenergic receptor kinase inhibitor to the failing heart reverses cardiac dysfunction. Circulation. 2001;103:1311–1316. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.9.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.White DC, Hata JA, Shah AS, Glower DD, Lefkowitz RJ, Koch WJ. Preservation of myocardial beta-adrenergic receptor signaling delays the development of heart failure after myocardial infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5428–5433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090091197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pleger ST, Most P, Boucher M, Soltys S, Chuprun JK, Pleger W, et al. Stable myocardial-specific AAV6-S100A1 gene therapy results in chronic functional heart failure rescue. Circulation. 2007;115:2506–2515. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.671701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Niwano K, Arai M, Koitabashi N, Watanabe A, Ikeda Y, Miyoshi H, et al. Lentiviral vector-mediated SERCA2 gene transfer protects against heart failure and left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction in rats. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1026–1032. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sasano T, McDonald AD, Kikuchi K, Donahue JK. Molecular ablation of ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction. Nat Med. 2006;12:1256–1258. doi: 10.1038/nm1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pleger ST, Shah C, Ksienzyk J, Bekeredjian R, Boekstegers P, Hinkel R, et al. Cardiac AAV9-S100A1 gene therapy rescues post-ischemic heart failure in a preclinical large animal model. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002097. 92ra64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Patten RD, Hall-Porter MR. Small animal models of heart failure. Development of novel therapies, past and present. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:138–144. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.839761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kloner RA, Jennings RB. Consequences of brief ischemia: stunning, preconditioning, and their clinical implications: part 1. Circulation. 2001;104:2981–2989. doi: 10.1161/hc4801.100038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kloner RA, Jennings RB. Consequences of brief ischemia: stunning, preconditioning, and their clinical implications: part 2. Circulation. 2001;104:3158–3167. doi: 10.1161/hc5001.100039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bridges CR, Gopal K, Holt DE, Yarnall C, Cole S, Anderson RB, et al. Efficient myocyte gene delivery with complete cardiac surgical isolation in situ. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:1364–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.White JD, Thesier DM, Swain JD, Katz MG, Tomasulo CE, Henderson A, et al. Myocardial gene delivery using molecular cardiac surgery with recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors in vivo. Gene Therapy. 2011;18:546–552. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kaye DM, Preovolos A, Marshall T, Byrne M, Hoshijima M, Hajjar RJ, et al. Percutaneous cardiac recirculation-mediated gene transfer of an inhibitory phospholamban peptide reverses advanced heart failure in large animals. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Byrne MJ, Power JM, Preovolos A, Mariani JA, Hajjar RJ, Kaye DM. Recirculating cardiac delivery of AAV2/1SERCA2a improves myocardial function in an experimental model of heart failure in large animals. Gene Therapy. 2008;15:1550–1557. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bridges CR. Recirculating method of cardiac gene delivery should be called ‘non-recirculating’ method. Gene Therapy. 2009;16:939–940. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kawase Y, Ladage D, Hajjar RJ. Rescuing the failing heart by targeted gene transfer. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1169–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jones JM, Petrofski JA, Wilson KH, Steenbergen C, Koch WJ, Milano CA. Beta2 adrenoreceptor gene therapy ameliorates left ventricular dysfunction following cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26:1161–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lillehei CW, DeWall RA, Gott VL, Varco RL. Direct vision correction of calcific aortic stenosis by means of pump-oxygenator and retrograde coronary sinus perfusion. Dis Chest. 1956;30:123–132. doi: 10.1378/chest.30.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Boekstegers P, Kupatt C. Current concepts and applications of coronary venous retroinfusion. Basic Res Cardiol. 2004;99:373–381. doi: 10.1007/s00395-004-0486-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Giordano FJ. Retrograde coronary perfusion: a superior route to deliver therapeutics to the heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1129–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00903-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Donahue JK, Kikkawa K, Johns DC, Marban E, Lawrence JH. Ultrarapid, highly efficient viral gene transfer to the heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4664–4668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Logeart D, Hatem SN, Heimburger M, Roux AL, Michel JB, Mercadier JJ. How to optimize in vivo gene transfer to cardiac myocytes: mechanical or pharmacological procedures? Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:1601–1610. doi: 10.1089/10430340152528101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fearon WF, Ikedo F, Bailey PR, Hiatt BL, Herity NA, Carter AJ, et al. Evaluation of high-pressure retrograde coronary coronary venous delivery of FGF-2 protein. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2004;61:422–428. doi: 10.1002/ccd.10790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rapti K, Chaanine AH, Hajjar RJ. Targeted gene therapy for the treatment of heart failure. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:265–283. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wasala NB, Shin J-H, Duan D. The evolution of heart gene delivery vectors. J Gene Med. 2011;13:557–565. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Katz MG, Swain JD, Fargnoli AS, Bridges CR. Gene therapy during cardiac surgery: role of surgical technique to minimize collateral organ gene expression. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010;11:727–731. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2010.244301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]