Background: Functions of short, cytosolic splice Bcl2 protein isoforms are unknown.

Results: TNFα provokes complexing of the splice isoform of Nix (sNix) to NFκB p65/RelA, their nuclear translocation, gene promoter binding, and suppressed expression.

Conclusion: sNix is a modifier of TNFα-mediated cardiomyocyte gene transcription.

Significance: sNix-TNFα interactions comprise a previously undescribed mechanism for cross-talk between extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways.

Keywords: Bcl-2 Family Proteins, Cardiovascular Disease, Gene Regulation, NF-kappa B (NF-KB), Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF), sNix

Abstract

Several Bcl2 family proteins are expressed both as mitochondrial-targeted full-length and as cytosolic truncated alternately spliced isoforms. Recombinantly expressed shorter Bcl2 family isoforms can heterotypically bind to and prevent mitochondrial localization of their full-length analogs, thus suppressing their activity by sequestration. This “sponge” role requires 1:1 expression stoichiometry; absent this an alternate role is suggested. Here, RNA sequencing revealed coordinate regulation of BH3-only protein Nix/Bnip3L (Nix) and its alternately spliced soluble form (sNix) in hearts, but relative sNix/Nix expression of ∼1:10. Accordingly, we examined other putative functions of sNix. Although Nix expressed in H9c2 rat myoblasts localized to mitochondria, sNix showed variable cytoplasmic and nuclear distribution. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) induced rapid and complete sNix nucleoplasmic translocation concomitant with nuclear translocation of the p65/RelA subunit of NFκB. sNix co-localized and co-precipitated with p65/RelA after TNFα stimulation; TNFα-induced sNix nuclear translocation did not occur in p65/RelA null murine embryonic fibroblasts. ChIP sequencing of TNFα-stimulated H9c2 cells revealed sNix suppression of p65/RelA binding to a subset of weaker DNA binding sites, accounting for its ability to alter gene expression in cultured cells and in vivo mouse hearts. These findings reveal TNFα-stimulated cytoplasmic-nuclear shuttling of the alternately spliced non-mitochondrial Nix isoform and uncover a role for sNix as a modulator of TNFα/NFκB-stimulated cardiac gene expression. Transcriptional co-regulation of sNix and Nix, combined with sNix posttranslational regulation by TNFα, comprises a previously unknown mechanism for molecular cross-talk between extrinsic death receptor and intrinsic mitochondrial apoptosis pathways.

Introduction

Organ function is determined in part by the fate of individual constituent cells. A shift in the normal dynamics of cell proliferation and programmed elimination can cause organ dysfunction or disease. Examples of clinical and experimental pathology induced by programmed cell death include heart failure (1) and diabetes (2), in which programmed cell death is provoked by disruption of the normal homeostatic balance between factors that mediate cell survival and cell death. Transcriptional up-regulation of the proapoptotic Bcl2 family mitochondrial protein Nix/Bnip3L has been linked to both diseases (3, 4).

Like other BH3-only Bcl-2 family members, Nix3 promotes outer mitochondrial membrane permeabilization by Bax and Bak, thus releasing mitochondrial cytochrome c into the cytosol and activating the caspase cascade (5–7). A fraction of Nix localizes to the endoplasmic reticulum and stimulates programmed cell necrosis by facilitating calcium-mediated opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (6, 8–10). Proapoptotic Nix, like its antiapoptotic counterparts Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL, is expressed as long and short isoforms generated via alternate mRNA splicing (5, 11, 12). Short Bcl-2 family splice isoforms lack essential organelle targeting domains and are therefore soluble proteins localized within the cytosol. By heterodimerizing with their full-length counterparts, it is thought that the short splice isoforms Bcl-2β and Bcl-XS sequester full-length Bcl-2α or Bcl-XL, respectively, thereby increasing sensitivity to apoptotic stimuli (12–15). Consistent with this “anti-parent protein” paradigm, the short splice isoform of Nix/Bnip3L (sNix for “short” or “spliced” Nix) can antagonize proapoptotic effects of full-length Nix through heterodimerization and sequestration (5). However, Nix-neutralizing activity of sNix was only observed when the latter was expressed in molar excess relative to Nix.

Here, we find that sNix is up-regulated to a greater extent than full-length Nix in genetic and pressure overload cardiac hypertrophy but is still expressed at far less than the 1:1 stoichiometric ratio necessary to inhibit apoptosis through Nix cytosolic sequestration. We discovered that sNix interacts with cytosolic NFκB p65/RelA and is conveyed to cell nuclei as a passenger on the p65/RelA complex in response to tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) stimulation. The presence of sNix in nuclear p65/RelA complexes negatively modulates NFκB-mediated gene expression in response to TNFα signaling. The consequence is molecular fine-tuning that modulates the dominant proapoptotic transcriptional response to this cytokine. This is a previously unknown function for short Bcl-2 family protein isoforms. Critical roles for both TNFα as the stimulus for and sNix as the modulator of NFκB-regulated gene expression uncover a new avenue of molecular cross-talk between extrinsic and intrinsic cell death pathways.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation and Characterization of Conditional sNix Transgenic Mice

Gαq transgenic mice and mice conditionally expressing cardiomyocyte Nix have been described (6, 16, 17). Conditional sNix transgenic mice were created with the same doxycycline-suppressible α-myosin heavy chain-driven system as for conditional Nix expression. Two founder lines for sNix were obtained, with similar phenotypes. Mice were housed and studied according to procedures approved by Animal Studies Committee at Washington University School of Medicine. M-mode echocardiography was performed using standard methods.

Transfected Cell Studies

p65/RelA null murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (18) were a gift from Dr. Alexander Hoffmann (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA). Wild-type MEFs were described previously (6). Cells were maintained in DMEM plus 10% serum at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and cultured up to passage 6. Unless specified, cells were infected with adenoviral constructs expressing β-galactosidase, Nix, or sNix in the pAdEasy-1 vector (Stratagene) (8) (100 PFUs/cell) for 24 h in normal culture medium (DMEM with 10% FBS) and then transferred to serum-free DMEM for 24 h.

Cells for confocal studies were plated on chamber slides (5 × 104 cells/well) and infected with recombinant adenoviruses (100 PFUs/cell) for examination at 36 or 48 h. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature followed by incubation in methanol for 20 min on ice. After three washes, cells were permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100-PBS and further blocked with 5% goat serum. Immunofluorescence staining used the following primary antibodies: mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG (1:1000 dilution, Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit polyclonal anti-p65/RelA (1:200 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), and rabbit polyclonal anti-lamin B1 (1:200 dilution, Cambridge, Abcam). Secondary antibodies were either Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (1:500 dilution, Invitrogen) or Alexa Fluor 546-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:500 dilution, Invitrogen) as appropriate. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI using VECTASHIELD mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). In some studies, cells were prestained with MitoTracker Red CMXRos (Invitrogen) for 30 min in culture medium before fixation. TUNEL staining used the DeadEnd fluorometric TUNEL assay (Promega). The pDsRed modified red fluorescent protein-p65/RelA expression plasmid was previously described (19). Cell viability assays used the LIVE/DEAD cell viability kit (Life Technologies). Fluorescence was analyzed using a Nikon C1si D-eclipse confocal microscope system and camera (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) with a Nikon plan Apo VC 60×/1.40 oil objective.

Subcellular Fractionation Studies

All fractionation procedures were performed at 4 °C. Hearts from 4-week neonatal mice were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in buffer containing 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, 320 mm sucrose, 3 mm MgCl2, 25 mm Na2P4O7, 1 mm DTT, 5 mm EGTA, 1 mm PMSF, and Complete mini protease inhibitor mixture tablet (Roche Applied Science). The homogenates were clarified at 100 × g to remove cellular and noncellular debris and then centrifuged at 3,800 × g for 10 min to collect nuclei. The supernatant was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min to obtain a mitochondria-enriched pellet. The supernatant was harvested after centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The cellular fraction was prepared the same way with heart subcellular fractionation.

Fractionated proteins were separated by electrophoresis on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk and 0.1% Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline before incubation with primary antibody (mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG (1:5000 dilution, Sigma-Aldrich), anti-α-tubulin (1:5000 dilution, Sigma-Aldrich), cytochrome oxidase IV (COX IV) (1:2000 dilution, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-lamin B1 (1:1000 dilution, Abcam), rabbit polyclonal anti-p65/RelA antibody (1:500 dilutions, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), goat polyclonal anti-Nix antibody (1:200 dilution, R&D Systems), and rabbit polyclonal anti-GAPDH antibody (1:1000 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Secondary antibodies were either goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) or goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:5000 dilution, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) as appropriate. Bands were visualized by chemiluminescence using the ECL-Plus reagent (GE Healthcare) and quantified using ImageJ.

ChIP Sequence Analysis of sNix and p65/RelA DNA Binding

Rat H9c2 cardiomyoblasts (from ATCC) were infected with adenoviruses expressing sNix or β-Gal control and then grown in DMEM with 1% FBS for 24 h followed by treatment with TNFα (20 ng/ml) or vehicle control for 3 h. ChIP assays were performed as described previously using anti-p65/RelA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog number sc-372x) (20).

The chromatin immunoprecipitation/DNA sequencing (ChIP-seq) libraries were prepared according to the Illumina protocol as described previously (20). Briefly, 10 ng of ChIP DNA was end-repaired, ligated to barcoded adaptors, size-selected on agarose gel (300–500 bp), and PCR-amplified for 16 cycles using Phusion polymerase (Finnzymes). The libraries were sequenced in the Illumina HiSeq2000 system according to the manufacturer's instructions. ChIP-seq reads were mapped to the rat genome using Bowtie version 0.12.1. Reads that did not map uniquely were disregarded. Site identification from short sequence reads (SISSRS) was used to identify p65/RelA binding sites, with input samples used as background and at a false discovery rate of 0.01. Peaks that mapped to rRNA or satellite repeats were disregarded because they cannot be properly mapped due to incomplete annotation. When p65/RelA binding peaks were within 750 bp in a given sample, only the larger peak was considered to avoid redundant detection.

Cardiac and H9c2 Transcriptional Profiling by RNA Sequencing

Detailed methods for preparation of Illumina RNA sequencing libraries have been published (21). Briefly, 4 μg of total RNA was twice selected by oligo(dT) using the Dynabeads mRNA purification system (Invitrogen). 200 ng of mRNA was heat-fragmented to ∼200 nucleotides at 94 °C for 2.5 min, chilled, and purified on Ambion NucAway columns. 100 ng of fragmented cardiac mRNA was reverse-transcribed using SuperScript III (Invitrogen) with random hexamers. cDNAs were end-repaired, and 3′ A-overhangs were added. Illumina adapters with T-overhangs customized to include three-nucleotide “barcodes” were ligated to the cDNA at 10:1 molar excess, and DNA in the 200–400-bp range was isolated via gel purification on 2% low melting agarose. The gel-purified libraries were PCR-amplified for 12 cycles using oligonucleotides complementary to Illumina sequencing adapters, column-purified, and quantified using PicoGreen (Quant-It, Invitrogen). Four barcoded libraries were combined in equimolar (10 nmol/liter) amounts and diluted to 6 pmol/liter for cluster formation on a single Illumina Genome Analyzer II flow cell lane followed by single-end sequencing. Base calling, library sorting by barcode, and mapping to the transcriptome were performed as described (21). Calculation of expression data and statistical analysis were performed using Partek Genomics Suite version 6.4 (Partek, St. Louis, MO) and mapped to the rat genome using Tophat version 1.0.14.

Quantitative PCR

To verify the enrichment of genomic DNA in ChIP-seq, ChIP DNA was subjected to SYBR Green qPCR using the following primers: Nfkbia forward, GGTTGTTCTGGAAGTTGAGGAAG, reverse, CCATGAAGAGAAGACACTGACCA; Nfkb2 forward, CCGGGTTGCTACAAGAGTCC, reverse, AATTCCCGTGACGTTCCTGT; Ccl2 forward, AAATATCTCTCCTGAAGGGTCTGG, reverse, TCCCACTCACTTTACTCTGTCAAC; negative control forward, CAACAATCTGCCCTGACAATTC, reverse, TTATGTCTGTGGGTGACAGCAG. The negative control PCR reaction was designed based on the background of ChIP-seq mapping and used to normalize the enrichment of p65 occupancy. To examine gene expression, SYBR Green RT-qPCR was performed using the following primers: Nfkbia forward, gagttgccctacgatgactgtg, reverse, gctgtgtgctgtggtgctaagt; Nfkb2 forward, AATCTGGGTGTCCTGCATGTAA, reverse, AAGGAAAGCTGAGAAGCGTAGC; Ccl2 forward, tgagtcggctggagaactacaa, reverse, ttctggacccattccttattgg; Gapdh forward, TGGGTGTGAACCACGAGAAATA, reverse, GCCATCCACAGTCTTCTGAGTG. Relative mRNA levels were normalized by Gapdh.

Statistical Analysis

Data are mean ± S.D. Student's t test was used for paired comparisons, and analysis of variance with Tukey's post-hoc test was used for multiple comparisons. p values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

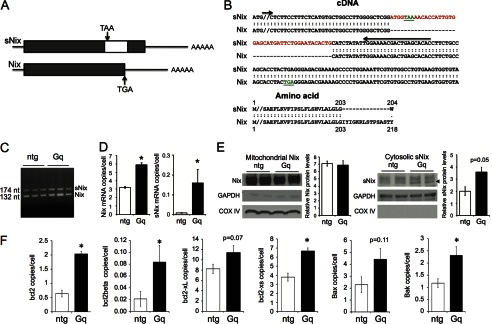

sNix Is Disproportionately Up-regulated in Cardiac Hypertrophy

Transcriptional regulation of Nix in murine and human cardiac hypertrophy has been observed by microarray profiling, Northern blot analysis, quantitative RT-PCR, and activity of a cardiac transgenic Nix promoter/luciferase promoter (5, 22, 23). The C-terminal truncated form of Nix (sNix) was described a decade ago as a product of alternate mRNA splicing in the heart (5) (Fig. 1, A and B), but its regulation in heart disease has not been reported because microarrays and conventional Northern blot analyses do not distinguish between Nix and sNix transcripts. We first addressed this question with PCR using primers that span the alternate splice region and therefore distinguish between the two transcripts. These semiquantitative results suggest that both long and short Nix isoforms are increased relative to normal hearts in the genetic cardiac hypertrophy induced by cardiomyocyte-specific expression of Gαq (Fig. 1C) (16, 24).

FIGURE 1.

Alternate mRNA splice isoform, sNix, is regulated in cardiac hypertrophy. A, schematic diagram depicting sNix and Nix cDNA structures. The white box inside the sNix open reading frame is an alternate exon encoding an early TAA termination codon (not to exact scale). B, top, aligned cDNA nucleotide sequences of sNix and Nix C-terminal regions showing alternately spliced insert (red) and position of termination codons (green). Bottom, corresponding aligned amino acid sequence. C, ethidium-stained gel showing sNix and Nix PCR products in nontransgenic (ntg) and Gαq transgenic (Gq) hearts; positions of PCR primers spanning the alternate exon are shown by arrows in B. D, quantitative sNix (left) and Nix (right) mRNA expression assayed by RNA sequencing of nontransgenic (white) and Gαq (black) hearts (n = 4 each, * = p < 0.05). E, immunoblot analyses showing mitochondrial Nix and cytosolic sNix protein levels in two nontransgenic and two Gαq hearts. Protein quantification was conducted using ImageJ and normalized by COX IV and GAPDH, respectively. F, quantitative analysis of splice isoform expression of other members of the Bcl2 family assayed as in D.

Because cytosolic sequestration of Nix by sNix requires approximately equal expression levels, we quantified cardiac sNix and Nix transcript abundance using deep mRNA sequencing (RNA-seq) (21). Full-length Nix mRNA was expressed at modest levels in normal hearts, averaging 3.2 ± 0.1 copies per cell. By contrast, sNix transcripts were detected in only one of four normal hearts, with a mean expression level of 0.009 ± 0.002 copies per cell (i.e. 0.3% of total Nix mRNA) (Fig. 1D, white bars). Thus, RNA-seq shows that Nix mRNA is rare and that sNix mRNA is expressed at insignificant levels in normal hearts. Nix mRNA is increased in Gαq-mediated and pressure overload hypertrophy when compared with control hearts, but quantitative Nix and sNix transcript abundance has never been established (5, 22, 23). RNA-seq revealed that Nix transcript levels increased 2-fold in Gαq transgenic hearts (6.0 ± 0.2 copies per cell, p = 1.5 × 10−8). Strikingly, sNix was detected in all Gαq transgenic hearts at levels that were an order of magnitude greater than the average among normal hearts (0.16 ± 0.07 copies per cell; p = 0.02 versus controls) (Fig. 1D, black bars). However, when compared with full-length Nix mRNA, sNix mRNA is present in hypertrophied hearts at only approximately one-thirtieth its levels. Comparative immunoblotting of mitochondrial Nix and cytosolic sNix confirmed far greater cardiac Nix than sNix expression and validated the finding that sNix is up-regulated in Gq-mediated hypertrophy (Fig. 1E).

We used RNA-seq to better understand sNix and Nix transcript abundance data in the context of transcript levels for other cardiac-expressed Bcl2 family proteins (Fig. 1F). Bcl-2 is expressed at a fraction of the level of Nix in normal hearts (0.6 ± 0.1 mRNA copies/cell) and is up-regulated by Gαq; its shorter splice isoform Bcl2β is also significantly up-regulated by Gαq (0.08 ± 0.03 copies per cell; p = 0.04). Bcl-XL is expressed at levels similar to Nix in normal hearts (8.2 ± 0.9 mRNA copies per cell) and is not significantly regulated in hypertrophy. However, its soluble isoform Bcl-XS is up-regulated in Gαq-expressing hearts (6.7 ± 0.3 copies per cell; p = 0.004). Bax and Bak are also expressed at levels similar to Nix in normal hearts (Bax, 2.3 ± 0.7; Bak, 1.2 ± 0.2 mRNA copies/cell), but only Bak is significantly up-regulated by Gαq. These results show that Nix and sNix mRNAs are expressed in hearts at levels comparable with those of other full-length and alternately spliced Bcl2 transcripts. sNix mRNAs levels increase in pathological cardiac hypertrophy, and its proportional up-regulation is greater than that of full-length Nix in the same hearts, although its absolute levels are only a fraction of those for Nix. The observed differences in relative expression of these long and short Bcl2 family isoforms challenge the notion that heterodimerization and sequestration of the longer Bcl2 protein isoforms by their shorter, alternately spliced products comprise the only functional mechanism for their effects.

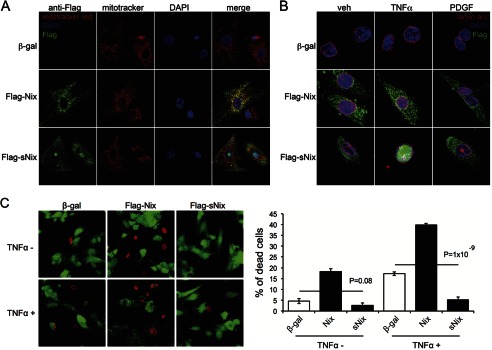

sNix Undergoes TNFα-stimulated Translocation to Cardiomyocyte Nuclei

Like other proapoptotic Bcl2 factors, Nix localizes to both mitochondria and endo-sarcoplasmic reticulum in cultured fibroblasts (5, 6, 8); sNix is a predominantly cytosolic protein (5). In comparative confocal studies of adenoviral Nix- and sNix-infected H9c2 rat cardiomyoblasts, Nix exhibited the expected co-localization with mitochondria (Fig. 2A, middle row), but sNix was variably present in cardiomyoblast cytosol and nuclei (Fig. 2A, bottom row) (full-length Nix was never observed in cardiomyoblast nuclei). Variable sNix nuclear localization was completely abrogated by serum deprivation for 24 h, after which sNix was exclusively cytoplasmic (Fig. 2B, veh). We postulated that the stabilizing effects of serum deprivation on cytosolic sNix accrued from depletion of serum-derived growth factors and/or cytokines and tested the notion that one or more serum-derived bioactive factors induce sNix nuclear transport. Indeed, application of TNFα to serum-deprived H9c2 cells promoted rapid and complete translocation of sNix from the cytoplasm to the nucleoplasm (Fig. 2B, bottom row), whereas platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) had no such effect (Fig. 2B, right column). Neither TNFα nor PDGF altered the characteristic mitochondrial targeting of full-length Nix (Fig. 2B, middle row). Thus, cytoplasmic-nuclear shuttling of sNix is induced by an apoptosis-inducing cytokine, but not by a cytoprotective growth factor. Importantly, although Nix induced H9c2 cell death that was further increased by TNFα treatment, sNix protected against TNFα-induced H9c2 cell death (Fig. 2C). Thus, nuclear sNix translocation is associated with protection against apoptosis.

FIGURE 2.

sNix nuclear translocation protects against TNFα-induced H9c2 cell death. A and B, confocal micrographs of H9c2 cells infected with control adeno-β-gal (top row), adeno-FLAG-Nix (middle row), or adeno-FLAG-sNix (bottom row). A, H9c2 cells under typical tissue culture conditions. Red = MitoTracker red; green = FLAG; blue = DAPI nuclear stain. B, H9c2 cells after 24-h serum deprivation without (veh, vehicle) or 60 min after treatment with TNFα (20 ng/ml) or PDGF (20 ng/ml). Red = lamin a/c labeling nuclear membrane; green = FLAG; blue = DAPI nuclear stain. C, fluorescent micrographs (left) showing live (green) and dead (red) H9c2 cells infected with control adeno-β-gal, adeno-FLAG-Nix, or adeno-FLAG-sNix after vehicle or TNFα (50 ng/ml) treatment for 24 h. The percentage of dead cells was calculated from three independent wells under each condition (right).

sNix Associates with and Requires NFκB p65/RelA to Undergo Nuclear Translocation

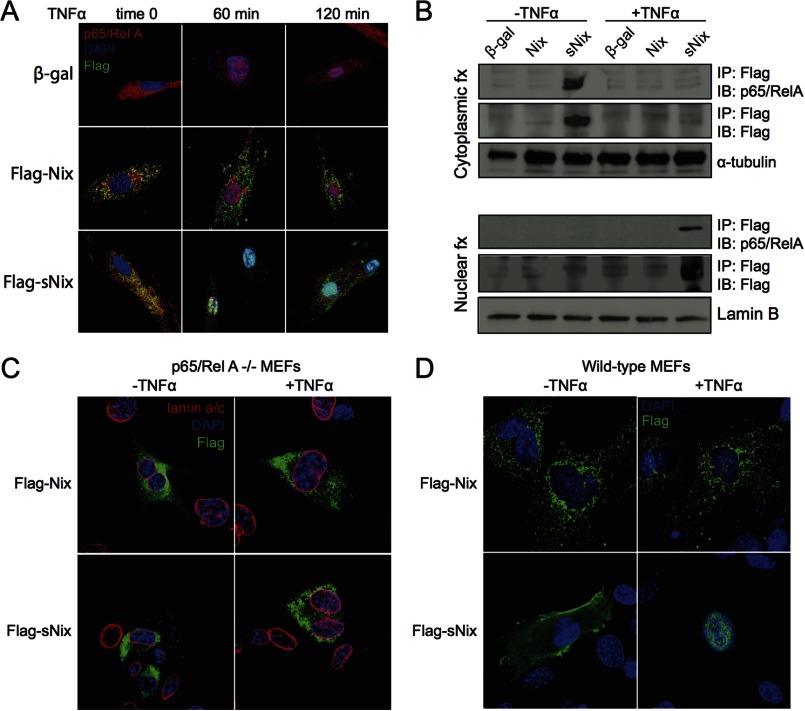

TNFα regulates the expression of genes, affecting cell growth, survival, and programmed death by interacting with its cognate membrane receptors to activate the heterodimeric transcription factor NFκB (25–27). Inactive NFκB is cytosolic, but upon cytokine stimulation, it is directed to the nucleus (28). Confocal studies of H9c2 cells revealed co-localization of sNix, but not Nix, with the p65/RelA component of NFκB in the cytosol of serum-deprived cells (Fig. 3A, left column). TNFα stimulated concomitant cytoplasmic-nuclear shuttling of sNix and p65/Rel A, whereas the longer Nix isoform remained extranuclear (Fig. 3A, middle and right columns). sNix and p65/RelA were retained in the nucleoplasm of TNFα-stimulated H9c2 cells for at least 2 h (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Association and co-translocation of sNix and NFκB p65/RelA to cell nuclei after TNFα stimulation. A, confocal micrographs of H9c2 cells expressing pDsRed modified red fluorescent protein-p65/RelA (red) β-gal control (top) or FLAG-Nix (middle) or FLAG-sNix (bottom). FLAG epitope stains green. Columns show nuclear translocation of red p65/RelA and sNix, but not Nix, 60 and 120 min after the addition of (20 ng/ml) TNFα. Co-localization of sNix and p65/RelA in cytosol before TNFα addition is indicated by yellow fluorescence at time 0. B, co-immunoprecipitation of sNix and p65/RelA from cytosol in unstimulated H9c2 cells and nucleoplasm in TNFα-stimulated H9c2 cells. fx = fraction; IP = immunoprecipitating antibody; IB = immunoblotting antibody. Tubulin and lamin B are loading controls for cytosol and nuclear fractions, respectively. C, the absence of TNFα-stimulated sNix nuclear translocation in p65/RelA null MEFs. Red = lamin a/c labeling nuclear membrane; green = FLAG; blue = DAPI nuclear stain. D. TNFα-stimulated sNix nuclear translocation in wild-type MEFs.

Because sNix and p65/RelA co-localize and co-migrate, we asked whether there was a direct physical interaction between the two proteins. TNFα-treated and untreated adeno-sNix-infected H9c2 cells were separated into cytoplasm- and nucleus-rich fractions, sNix was immunoprecipitated using an antibody directed against the FLAG epitope, and associated NFκB p65/RelA was identified by immunoblotting. p65/RelA co-immunoprecipitated with sNix, but not Nix, in the cytosolic fraction of TNFα unstimulated cells (Fig. 3B, top). After TNFα stimulation, sNix-p65/RelA immune complexes were detected in the nuclear, but not cytosolic compartment (Fig. 3B, bottom). Thus, sNix and NFκB p65/RelA are physically associated in cytosol and nuclei and undergo TNFα-stimulated co-transportation to cell nuclei.

To determine whether there is a requirement for p65/RelA in TNFα-induced sNix nuclear translocation, we repeated the TNFα stimulation studies in MEFs derived from p65/RelA knock-out mice (18). TNFα-stimulated nuclear sNix translocation was not observed in p65/RelA null MEFs (Fig. 3C), but wild-type MEFs showed the same sNix translocation observed in H9c2 cells (Fig. 3D). Together, the above results demonstrate that sNix is a passenger on NFκB p65/RelA complexes that undergo nuclear translocation in response to TNFα.

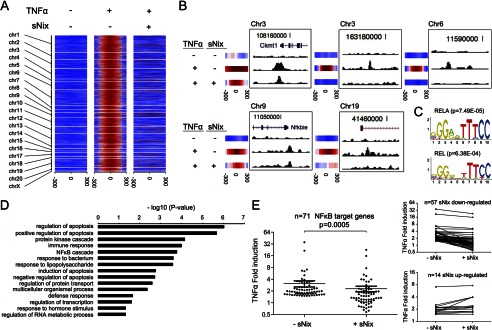

sNix Suppresses TNFα-stimulated NFκB p65/RelA DNA Binding and Gene Expression

Because sNix and p65/RelA interact and are co-transported to nuclei of TNFα-stimulated H9c2 cells, we asked how sNix affects TNFα-stimulated NFκB p65/RelA DNA binding using ChIP-seq. H9c2 cells with or without sNix were examined before and after TNFα stimulation for 3 h; immunoprecipitation with anti-p65/RelA was performed to identify DNA sites bound by NFκB. Aggregate ChIP-seq read counts within 0.3 kb of the binding peaks for individual TNFα-induced p65/RelA ChIP-seq signal intensities, illustrated genome-wide by chromosomal location, showed that p65/RelA DNA binding is minimal in the absence of TNFα (Fig. 4A, left column). This is consistent with the requirement for TNFα to promote p65/RelA nuclear localization (see above). ChIP-seq identified 2,101 p65/RelA binding sites (supplemental Table S1) stimulated by TNFα treatment (red events in the middle column of Fig. 4A). sNix attenuated binding to over 90% of the TNFα-stimulated p65/RelA binding sites (loss of red events in right columns of Fig. 4A). Occupation by p65/RelA of 145 sites was unaffected by sNix, although the ChIP-seq signal intensities within these regions seemed attenuated. Specific examples of different sNix regulatory patterns showing raw ChIP-seq data and their corresponding signal intensity heat maps are provided in Fig. 4B. In addition, a de novo motif search showed that the NFκB response element is the most prevalent motif identified in p65/RelA binding sites (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

TNFα-stimulated NFκB signaling is suppressed after sNix expression in H9c2 cardiac myoblasts. A, heat map depiction of genome-wide ChIP-seq signal intensity of H9c2 cells as a function of proximity to bioinformatically predicted p65/RelA binding sites. Results are shown with and without TNFα and sNix. chr, chromosome. B, five genetic examples showing individual p65/RelA ChIP-seq intensities for the different experimental conditions and corresponding heat map plots. C, top two transcription factor motifs (RELA and REL) discovered at repeat-masked p65/RelA binding sites using the MEME Suite. Top 100 p65/RelA peaks (by ChIP-seq -fold change) were used for de novo motif search. D, summary of gene ontology analysis using DAVID for 71 TNFα-regulated genes. The gene ontology categories are ranked by the log10 p values for disproportionate representation. E, TNFα-induced gene regulation (log2 of -fold induction for the 71 TNFα-regulated genes) in the absence and presence of sNix. A paired two-tailed t test was used to calculate the p value. Insets to the right show individual regulation of sNix suppressed (top) and nonsuppressed mRNAs.

To understand the genome-wide consequences of sNix on TNFα-stimulated, p65/RelA-mediated gene expression, we performed deep mRNA sequencing of H9c2 cardiac myoblasts before and after TNFα stimulation for 12 h. Of 28,358 annotated rat mRNAs in Ensemble gene annotation, RNA-seq identified 12,125 H9c2 mRNAs expressed at a level of one copy per cell or greater (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) >3, supplemental Table S2). Adenoviral expression of sNix had little effect on this base-line transcriptional signature, whereas stimulation by TNFα increased expression of 925 mRNAs by 1.5-fold. There was a positive correlation between gene proximity to an identified TNFα-induced p65/RelA DNA binding site and the likelihood of TNFα regulation (p = 1.5 × 10−5, determined by a hypergeometric test); 71 annotated and identifiable genes proximate to p65 binding sites were up-regulated at least 50% by TNFα (supplemental Table S3). Gene ontology analysis of these 71 genes using DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery) (29) identified over-representation in the following functional categories: Regulation of Apoptosis (n = 12, p = 9.74 × 10−7), Immune Response (n = 8, p = 1.03 × 10−4), and NFκB Cascade (n = 4, p = 1.71 × 10−4) (Fig. 4D). Notably, sNix significantly attenuated most of these 71 TNFα-stimulated genes in H9c2 cells. The average TNFα -fold induction decreased from 3.2 ± 0.6 to 2.4 ± 0.4 (Fig. 4E), although a few genes were either modestly up-regulated by sNix or not changed (Fig. 4E, lower inset panel).

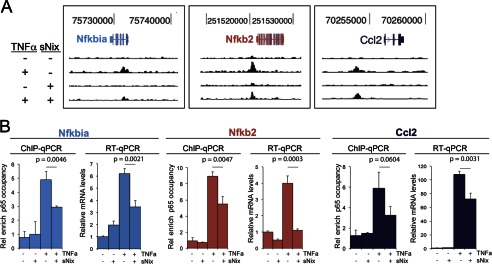

To validate the role of sNix as a suppressor of NFκB-mediated gene expression, we reanalyzed three TNFα-up-regulated NFκB target genes (Nfkbia, Nfkb2, and Ccl2) with strong nearby p65/RelA binding sites using independent site-specific ChIP-qPCR and RT-qPCR (Fig. 5). sNix significantly diminished TNFα-induced p65/RelA occupancies at these loci and inhibited TNFα-stimulated gene expression.

FIGURE 5.

Validating studies showing that sNix suppresses TNFα-induced p65/RelA occupancies and inhibits TNFα-stimulated NFκB target gene expression. A, representative ChIP-qPCR determinations of TNFα and sNix effects on p65/RelA binding intensities within three sNix-suppressible H9c2 cell-expressed NFκB target genes. B, group mean data and intergroup comparisons for ChIP-qPCR and RT-qPCR for the same genes as in A. Data are mean ± S.D. of three PCR reactions. Rel enrich, relative enrichment.

sNix Modifies in Vivo Cardiac Transcription

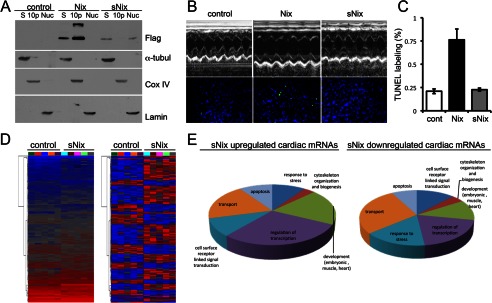

The above studies show that sNix can act as a transcriptional modifier of cell death genes in tissue culture. We next asked whether sNix could also modify in vivo cardiomyocyte gene expression, comparing novel conditional cardiomyocyte-specific transgenic sNix mice with previously described full-length Nix-expressing mice (6, 17). As in cultured cells, sNix co-localized with both α-tubulin in cytoplasm and lamin in nuclear myocardial fractions (Fig. 6A). sNix was not detected in the COX IV-rich mitochondrial fraction (Fig. 6A). In contrast, full-length Nix was entirely extranuclear and largely mitochondrial (Fig. 6A), consistent with previous studies (6, 8). sNix transgenic mice did not develop the characteristic cardiac enlargement or decreased contractile performance induced by programmed cardiomyocyte death in full-length Nix transgenic mice. Echocardiographic left ventricular mass (sNix, 3.4 ± 0.2 mg/g versus 3.3 ± 0.4 control), diastolic dimension (sNix, 2.98 ± 0.08 mm versus 2.96 ± 0.05 control), and fractional shortening (sNix, 68 ± 2% versus 70 ± 1% control) were all normal (Fig. 6B, upper row). Likewise, there was no significant cardiomyocyte TUNEL positivity as seen in cardiac Nix transgenic mice (6) (Fig. 6B, lower row, and Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Cardiomyocyte-expressed sNix is localized in nuclei and cytoplasm and alters cardiac gene expression without inducing apoptosis or cardiomyopathy. A, immunoblot analysis of FLAG-Nix and -sNix myocardial fractions in Nix and sNix transgenic mouse hearts. S = supernatant cytosolic fraction labeled by α-tubulin (α-tubul); 10p = 10,000 × g pellet enriched in mitochondrial proteins marked by COX IV; Nuc = nuclear fraction labeled by lamin. B, representative M-mode echocardiograms (top) and fluorescent TUNEL staining (bottom) from control, Nix, and sNix hearts. Quantitative group echocardiographic measures are under “Results.” C, quantitative group data for TUNEL labeling (n = 5 each group). cont, control. D, unsupervised hierarchical clustering of sNix-regulated cardiac gene expression. Left, raw reads; right, normalized reads. Each column is one individual mouse heart. E, results of gene ontology analysis of sNix-regulated cardiac mRNAs.

Although sNix expression in mouse hearts was completely benign, we used highly sensitive RNA-seq to determine whether sNix can modify cardiac gene expression. We identified a number of highly reproducible sNix-regulated transcripts (Fig. 6D, supplemental Table S4) that are disproportionately represented in gene ontology categories relating to cell death/survival and gene transcription (Fig. 6E). Thus, sNix, which itself is a regulated cardiac gene, is sufficient to modulate the expression of other mouse heart genes.

DISCUSSION

Here, we show that the minor alternatively spliced short isoform of Nix/BNip3L, sNix, is a transcriptional modifier of TNFα/NFκB-mediated gene expression. Although we had occasionally observed immunoreactive sNix in confocal studies of cultured HEK293 cell nuclei,4 nuclear localization was inconsistent. We therefore attributed it to equal partitioning of a soluble protein to cytoplasm and nucleoplasm, with the apparent nuclear signal resulting from greater z axis density in cultured cell nuclei. In this we were misled by conventional wisdom (5, 11, 12). Instead, sNix is specifically directed to cell nuclei by TNFα, complexing with the p65/RelA component of NFκB and negatively (albeit modestly) modulating TNFα/NFκB-regulated genes that induce programmed cell death.

TNFα and NFκB both induce complex gene programs that can alter the homeostatic balance in favor of cell survival or cell death, depending upon pathophysiological context (25–27). Here, TNFα and NFκB induce gene expression favoring cell death pathways in cardiomyocytes, consistent with their proposed role in cardiomyocyte apoptosis and heart failure (30, 31). The net effect of sNix on NFκB p65/RelA-mediated gene expression is to reorient TNFα-induced NFκB signaling in favor of cytoprotection. We find it useful to conceptualize these molecular events as a college spring break trip to the beach. TNFα and NFκB are old friends who, when they get together, rent a microbus and head to the beach (nucleus) to engage in various destructive behaviors (programmed cell death). sNix is the older brother who tags along in the back of the microbus and restrains some of the beach activity without completely eliminating the party.

A decade ago, we described the truncated Nix isoform as a product of alternate mRNA splicing and determined that it antagonizes the proapoptotic effects of full-length Nix (5). These results led us to conclude that sNix heterodimerized with and sequestered full-length Nix in the cytosol. However, the concept that sNix could function in a meaningful way as an anti-Nix requires approximately equal expression of the two proteins, which we show is not the case. Indeed, hypertrophied hearts express sNix at levels sufficient to heterodimerize with and neutralize only a small fraction of endogenous Nix.

The sNix-Nix heterodimerization and cytosolic sequestration model also assumes that sNix is exclusively cytosolic, which we now find is contextual. The order of magnitude difference in Nix and sNix expression, its nuclear translocation in response to TNFα, and its incorporation into a p65/RelA transcriptional complex that directly binds DNA uncover an additional functional mechanism by which sNix can protect against apoptosis: modulation of TNFα/NFκB-induced gene expression. As Nix is a mitochondria-targeted death protein that stimulates apoptosis through the intrinsic pathway, whereas TNFα stimulates apoptosis through the extrinsic or death receptor pathway (32), modification of TNFα-stimulated gene expression by sNix represents a previously unsuspected avenue for cross-talk between the extrinsic death receptor and intrinsic mitochondrial apoptosis pathways.

The current results add to the growing list of diverse functions for Nix as a mediator of apoptosis, programmed cell necrosis, and mitophagy. Nix (aka BNip3L) is one of the small BNip subclass of proapoptotic BH3-only Bcl2 family proteins best known for interacting with and activating pore-forming Bax and Bak in mitochondrial outer membranes (33, 34). Nix-mediated cell death seems not to play an essential role during embryonic development, as three independently produced germ line Nix knock-out mice lack developmental abnormalities (35–37). Critical roles for Nix are, however, revealed by its essential homeostatic effects in different adult tissues; Nix-mediated apoptosis in erythroblasts regulates erythrocyte formation in opposition to erythropoietin (35). Nix stimulation of mitophagy in maturing erythroblasts is essential to prevent hemolysis of circulating erythrocytes (36, 37) and is necessary to prevent cardiomyopathy caused by retention of senescent cardiomyocyte mitochondria (38). Transcriptional up-regulation of Nix is the mechanism for programmed death of insulin-producing pancreatic β-cells in diabetes resulting from haploinsufficiency of the pancreatic and duodenal transcription factor, Pdx1 (4). In the heart, transcriptional up-regulation of Nix causes progression from compensated hypertrophy to cardiomyopathic heart failure by stimulating intrinsic pathway cardiomyocyte apoptosis (3). Finally, Nix mediates cardiomyocyte necrosis induced by the mitochondrial permeability transition and sarcoplasmic reticular-mitochondrial calcium exchange (6, 8).

Except for its initial description (5), sNix has largely been overlooked. Thus, our observation that sNix undergoes nuclear translocation and can act as a transcriptional suppressor was unexpected. Bioinformatics assessment of Nix and sNix amino acid sequences shows no nuclear localization sequence. Indeed, sNix is not independently targeted to the nucleus. Rather, it “piggy-backs” with NFκB p65/RelA to cell nuclei after stimulation by TNFα and limits the transcriptional effects of TNFα by neutralizing up-regulation mediated by weaker p65/RelA-DNA binding events while preserving expression of stronger targets.

In a broader context, the current results add an additional layer of complexity to the mechanisms by which Bcl-2 family proteins can regulate cell fate. Since their initial description in Caenorhabditis elegans (39), ced/Bcl2 family members have been assigned greater and greater functional diversity. In addition to their canonical roles as the gatekeepers of mitochondrial (intrinsic pathway) apoptosis (40), Bcl2 family members may regulate endoplasmic reticulum calcium homeostasis (41), autophagic mitochondrial clearance (36), macroautophagy (42), the unfolded protein response (43), and the mitochondrial permeability transition (6). Importantly, all of these effects depend upon localization of the Bcl2 factor to mitochondrial or endoplasmic reticular membranes, or both. For this reason, it has been widely thought that the only possible function for soluble cytosolic Bcl-2 family splice isoforms lacking transmembrane helical domains is binding to the full-length molecule, thereby preventing mitochondrial localization. By definition, such heterodimerization requires a 1:1 stoichiometry between the soluble and full-length proteins, which is not observed for any of the alternatively spliced Bcl-2 family factors. Nontargeted Nix and sNix are also rapidly degraded by the proteasome/ubiquitin system (5, 44, 45), making it unlikely that soluble sNix (or other Bcl-2 factors) is sufficiently stable to pair up with and sequester its full-length counterpart.

The role we have described for sNix as an inducible transcriptional modulator resolves apparent discrepancies relating to its low expression level. First, sNix expression in hypertrophied hearts (0.16 copies per cell) is not only similar to that of the soluble forms of Bcl-2 (0.08 copies per cell) in the same hearts, but is consistent with that of several other transcription factors, e.g. Foxo6 (0.20 copies per cell), Foxm1 (0.17 copies per cell), Foxp2 (0.016 copies per cell), Foxp3 (0.09 copies per cell), and Foxc2 (0.09 copies per cell). Second, rather than simply being an inert Nix sponge, sNix is a biologically active transcriptional modifier that has an entirely distinct molecular function. Finally, although co-expression of sNix and Nix from the same transcript makes less sense if sNix simply antagonizes Nix, co-expression and differential splicing of the two Nix isoforms with selective activation (translocation) of sNix in response to TNFα comprise an elegant mechanism for fine-tuning the biological response to concomitant intrinsic and extrinsic stimuli.

In most diseases wherein Bcl-2 proteins are dysregulated, transcriptional or post-translational mechanisms are implicated (46). In our murine cardiomyopathy model, RNA sequencing showed that regulated expression and splicing of Nix mRNA transcripts occurred simultaneously. This raises the possibility of preventing programmed cell death by redirecting mRNA splicing (47). For Nix, directing mRNA splicing in favor of sNix would have two potentially beneficial effects. Adjusting the relative proportion of the two proteins closer to 1:1 would reproduce the prosurvival effect observed with co-transfection in HEK cells (5), and increasing sNix expression would favorably affect gene expression. Determining whether this paradigm will also apply to other alternately spliced cytosolic Bcl-2 family members requires additional study.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 HL059888 through the NHLBI (to G. W. D.).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1–S4.

Y. Chen, K. F. Decker, D. Zheng, S. J. Matkovich, L. Jia, and G. W. Dorn II, unpublished data.

- Nix

- Nix/Bnip3L

- sNix

- short splice isoform of Nix

- MEF

- murine embryonic fibroblast

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- ChIP-seq

- ChIP/DNA sequencing

- RNA-seq

- deep mRNA sequencing.

REFERENCES

- 1. Whelan R. S., Kaplinskiy V., Kitsis R. N. (2010) Cell death in the pathogenesis of heart disease: mechanisms and significance. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 72, 19–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dorn G. W., 2nd (2010) Mechanisms of non-apoptotic programmed cell death in diabetes and heart failure. Cell Cycle 9, 3442–3448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Diwan A., Wansapura J., Syed F. M., Matkovich S. J., Lorenz J. N., Dorn G. W., 2nd (2008) Nix-mediated apoptosis links myocardial fibrosis, cardiac remodeling, and hypertrophy decompensation. Circulation 117, 396–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fujimoto K., Ford E. L., Tran H., Wice B. M., Crosby S. D., Dorn G. W., 2nd, Polonsky K. S. (2010) Loss of Nix in Pdx1-deficient mice prevents apoptotic and necrotic β cell death and diabetes. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 4031–4039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yussman M. G., Toyokawa T., Odley A., Lynch R. A., Wu G., Colbert M. C., Aronow B. J., Lorenz J. N., Dorn G. W., 2nd (2002) Mitochondrial death protein Nix is induced in cardiac hypertrophy and triggers apoptotic cardiomyopathy. Nat. Med. 8, 725–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen Y., Lewis W., Diwan A., Cheng E. H., Matkovich S. J., Dorn G. W., 2nd (2010) Dual autonomous mitochondrial cell death pathways are activated by Nix/BNip3L and induce cardiomyopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 9035–9042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scorrano L., Korsmeyer S. J. (2003) Mechanisms of cytochrome c release by proapoptotic BCL-2 family members. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 304, 437–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Diwan A., Matkovich S. J., Yuan Q., Zhao W., Yatani A., Brown J. H., Molkentin J. D., Kranias E. G., Dorn G. W., 2nd (2009) Endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria crosstalk in NIX-mediated murine cell death. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 203–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oakes S. A., Opferman J. T., Pozzan T., Korsmeyer S. J., Scorrano L. (2003) Regulation of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ dynamics by proapoptotic BCL-2 family members. Biochem. Pharmacol. 66, 1335–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kitsis R. N., Molkentin J. D. (2010) Apoptotic cell death “Nixed” by an ER-mitochondrial necrotic pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 9031–9032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hockenbery D., Nuñez G., Milliman C., Schreiber R. D., Korsmeyer S. J. (1990) Bcl-2 is an inner mitochondrial membrane protein that blocks programmed cell death. Nature 348, 334–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boise L. H., González-García M., Postema C. E., Ding L., Lindsten T., Turka L. A., Mao X., Nuñez G., Thompson C. B. (1993) bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell 74, 597–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tsujimoto Y., Croce C. M. (1986) Analysis of the structure, transcripts, and protein products of bcl-2, the gene involved in human follicular lymphoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 5214–5218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tanaka S., Saito K., Reed J. C. (1993) Structure-function analysis of the Bcl-2 oncoprotein: addition of a heterologous transmembrane domain to portions of the Bcl-2 β protein restores function as a regulator of cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 10920–10926 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Minn A. J., Boise L. H., Thompson C. B. (1996) Bcl-xS antagonizes the protective effects of Bcl-xL. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 6306–6312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. D'Angelo D. D., Sakata Y., Lorenz J. N., Boivin G. P., Walsh R. A., Liggett S. B., Dorn G. W., 2nd (1997) Transgenic Gαq overexpression induces cardiac contractile failure in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 8121–8126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Syed F., Odley A., Hahn H. S., Brunskill E. W., Lynch R. A., Marreez Y., Sanbe A., Robbins J., Dorn G. W., 2nd (2004) Physiological growth synergizes with pathological genes in experimental cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 95, 1200–1206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beg A. A., Sha W. C., Bronson R. T., Ghosh S., Baltimore D. (1995) Embryonic lethality and liver degeneration in mice lacking the RelA component of NF-κB. Nature 376, 167–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nelson D. E., Ihekwaba A. E., Elliott M., Johnson J. R., Gibney C. A., Foreman B. E., Nelson G., See V., Horton C. A., Spiller D. G., Edwards S. W., McDowell H. P., Unitt J. F., Sullivan E., Grimley R., Benson N., Broomhead D., Kell D. B., White M. R. (2004) Oscillations in NF-κB signaling control the dynamics of gene expression. Science 306, 704–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Decker K. F., Zheng D., He Y., Bowman T., Edwards J. R., Jia L. (2012) Persistent androgen receptor-mediated transcription in castration-resistant prostate cancer under androgen-deprived conditions. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 10765–10779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Matkovich S. J., Zhang Y., Van Booven D. J., Dorn G. W., 2nd (2010) Deep mRNA sequencing for in vivo functional analysis of cardiac transcriptional regulators: application to Gαq. Circ. Res. 106, 1459–1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aronow B. J., Toyokawa T., Canning A., Haghighi K., Delling U., Kranias E., Molkentin J. D., Dorn G. W., 2nd (2001) Divergent transcriptional responses to independent genetic causes of cardiac hypertrophy. Physiol. Genomics 6, 19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gálvez A. S., Brunskill E. W., Marreez Y., Benner B. J., Regula K. M., Kirschenbaum L. A., Dorn G. W., 2nd (2006) Distinct pathways regulate proapoptotic Nix and BNip3 in cardiac stress. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 1442–1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sakata Y., Hoit B. D., Liggett S. B., Walsh R. A., Dorn G. W., 2nd (1998) Decompensation of pressure-overload hypertrophy in Gαq-overexpressing mice. Circulation 97, 1488–1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bergmann M. W., Loser P., Dietz R., von Harsdorf R. (2001) Effect of NF-κB inhibition on TNF-α-induced apoptosis and downstream pathways in cardiomyocytes. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 33, 1223–1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kubota T., Miyagishima M., Frye C. S., Alber S. M., Bounoutas G. S., Kadokami T., Watkins S. C., McTiernan C. F., Feldman A. M. (2001) Overexpression of tumor necrosis factor-α activates both anti- and pro-apoptotic pathways in the myocardium. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 33, 1331–1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Higuchi Y., McTiernan C. F., Frye C. B., McGowan B. S., Chan T. O., Feldman A. M. (2004) Tumor necrosis factor receptors 1 and 2 differentially regulate survival, cardiac dysfunction, and remodeling in transgenic mice with tumor necrosis factor-α-induced cardiomyopathy. Circulation 109, 1892–1897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wajant H., Pfizenmaier K., Scheurich P. (2003) Tumor necrosis factor signaling. Cell Death Differ. 10, 45–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huang da W., Sherman B. T., Lempicki R. A. (2009) Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ceconi C., Curello S., Bachetti T., Corti A., Ferrari R. (1998) Tumor necrosis factor in congestive heart failure: a mechanism of disease for the new millennium? Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 41, 25–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gordon J. W., Shaw J. A., Kirshenbaum L. A. (2011) Multiple facets of NF-κB in the heart: to be or not to NF-κB. Circ. Res. 108, 1122–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen G., Goeddel D. V. (2002) TNF-R1 signaling: a beautiful pathway. Science 296, 1634–1635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boyd J. M., Malstrom S., Subramanian T., Venkatesh L. K., Schaeper U., Elangovan B., D'Sa-Eipper C., Chinnadurai G. (1994) Adenovirus E1B 19 kDa and Bcl-2 proteins interact with a common set of cellular proteins. Cell 79, 341–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim H., Tu H. C., Ren D., Takeuchi O., Jeffers J. R., Zambetti G. P., Hsieh J. J., Cheng E. H. (2009) Stepwise activation of BAX and BAK by tBID, BIM, and PUMA initiates mitochondrial apoptosis. Mol. Cell 36, 487–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Diwan A., Koesters A. G., Odley A. M., Pushkaran S., Baines C. P., Spike B. T., Daria D., Jegga A. G., Geiger H., Aronow B. J., Molkentin J. D., Macleod K. F., Kalfa T. A., Dorn G. W., 2nd (2007) Unrestrained erythroblast development in Nix−/− mice reveals a mechanism for apoptotic modulation of erythropoiesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 6794–6799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schweers R. L., Zhang J., Randall M. S., Loyd M. R., Li W., Dorsey F. C., Kundu M., Opferman J. T., Cleveland J. L., Miller J. L., Ney P. A. (2007) NIX is required for programmed mitochondrial clearance during reticulocyte maturation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 19500–19505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sandoval H., Thiagarajan P., Dasgupta S. K., Schumacher A., Prchal J. T., Chen M., Wang J. (2008) Essential role for Nix in autophagic maturation of erythroid cells. Nature 454, 232–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dorn G. W., 2nd (2010) Mitochondrial pruning by Nix and BNip3: an essential function for cardiac-expressed death factors. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 3, 374–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ellis H. M., Horvitz H. R. (1986) Genetic control of programmed cell death in the nematode C. elegans. Cell 44, 817–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wei M. C., Zong W. X., Cheng E. H., Lindsten T., Panoutsakopoulou V., Ross A. J., Roth K. A., MacGregor G. R., Thompson C. B., Korsmeyer S. J. (2001) Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science 292, 727–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Scorrano L., Oakes S. A., Opferman J. T., Cheng E. H., Sorcinelli M. D., Pozzan T., Korsmeyer S. J. (2003) BAX and BAK regulation of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+: a control point for apoptosis. Science 300, 135–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chang N. C., Nguyen M., Germain M., Shore G. C. (2010) Antagonism of Beclin 1-dependent autophagy by BCL-2 at the endoplasmic reticulum requires NAF-1. EMBO J. 29, 606–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Klee M., Pallauf K., Alcalá S., Fleischer A., Pimentel-Muiños F. X. (2009) Mitochondrial apoptosis induced by BH3-only molecules in the exclusive presence of endoplasmic reticular Bak. EMBO J. 28, 1757–1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen G., Cizeau J., Vande Velde C., Park J. H., Bozek G., Bolton J., Shi L., Dubik D., Greenberg A. (1999) Nix and Nip3 form a subfamily of pro-apoptotic mitochondrial proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 7–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cizeau J., Ray R., Chen G., Gietz R. D., Greenberg A. H. (2000) The C. elegans orthologue ceBNIP3 interacts with CED-9 and CED-3 but kills through a BH3- and caspase-independent mechanism. Oncogene 19, 5453–5463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cory S., Adams J. M. (2002) The Bcl2 family: regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 647–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mercatante D. R., Bortner C. D., Cidlowski J. A., Kole R. (2001) Modification of alternative splicing of Bcl-x pre-mRNA in prostate and breast cancer cells. analysis of apoptosis and cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 16411–16417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.