Background: The current structural model of Streptococcus pneumoniae lipoteichoic acid reveals inconsistencies.

Results: High resolution NMR and MS analysis of O-deacylated pnLTA allowed a precise revision of its structure.

Conclusion: The novel structure presented here is in complete agreement with known structural, biosynthetic, and immunological data.

Significance: This study will aid in further understanding the biosynthesis and inflammatory potency of pneumococcal (lipo)teichoic acids.

Keywords: Analytical Chemistry, Innate Immunity, Mass Spectrometry (MS), NMR, Structural Biology, Forssman Antigen, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Immunostimulatory Potency, Lipoteichoic Acid

Abstract

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a Gram-positive human pathogen with a complex lipoteichoic acid (pnLTA) structure. Because the current structural model for pnLTA shows substantial inconsistencies, we reinvestigated purified and, more importantly, O-deacylated pnLTA, which is most suitable for NMR spectroscopy and electrospray ionization-MS spectrometry. We analyzed pnLTA of nonencapsulated pneumococcal strains D39Δcps and TIGR4Δcps, respectively. The data obtained allowed us to (re)define (i) the position and linkage of the repeating unit, (ii) the putative α-GalpNAc substitution at the ribitiol 5-phosphate (Rib-ol-5-P), and (iii) the length of (i.e. the number of repeating units in) the pnLTA chain. We here also describe for the first time that the terminal sugar residues in the pnLTA (Forssman disaccharide; α-d-GalpNAc-(1→3)-β-d-GalpNAc-(1→)), responsible for the cross-reactivity with anti-Forssman antigen antibodies, can be heterogeneous with respect to its degree of phosphorylcholine substitution in both O-6-positions. To assess the proinflammatory potency of pnLTA, we generated a (lipopeptide-free) Δlgt mutant of strain D39Δcps, isolated its pnLTA, and showed that it is capable of inducing IL-6 release in human mononuclear cells, independent of TLR2 activation. This finding was quite in contrast to LTA of the Staphylococcus aureus SA113Δlgt mutant, which did not activate human mononuclear cells in our experiments. Remarkably, this is also contrary to various other reports showing a proinflammatory potency of S. aureus LTA. Taken together, our study refines the structure of pnLTA and indicates that pneumococcal and S. aureus LTAs differ not only in their structure but also in their bioactivity.

Introduction

Besides peptidoglycan (PGN),3 lipoproteins (LPs), and wall teichoic acid (WTA), lipoteichoic acid (LTA) is the major constituent of the Gram-positive bacterial cell wall. Whereas WTA is covalently bound to the PGN layers, LTA is non-covalently anchored in the cell membrane via a diacylglycerol (DAG)-containing lipid anchor (1). In comparison with LTA and WTA of other Gram-positive bacteria, Streptococcus pneumoniae (the pneumococcus), one of the most important Gram-positive pathogens, possesses a structurally unique, complex LTA (2, 3) belonging to type IV (4). Most remarkably, pneumococcal WTA and pneumococcal LTA (pnLTA) possess the same structure within the repeating units (RU) (5).

Another important structural feature is that both pneumococcal teichoic acids are highly decorated with phosphorylcholine (P-Cho) (6). These P-Cho residues serve as anchors for surface-exposed choline-binding proteins, which have immune protective potential (e.g. shown for pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA)) or for choline-binding proteins that are involved in essential physiological functions of S. pneumoniae, such as cell wall turnover (autolysins LytA, LytB, and LytC) and bacterial adhesion to host cells (PspC (also referred to as CbpA) and Pce (phosphorylcholine esterase, also known as CbpE)) (7–9). Moreover, P-Cho residues have been assigned to show a direct virulent function by mediating adherence to the receptor for platelet-activating factor (10, 11).

The original and long accepted structural model of pnLTA (12) was revised in 2008 by Seo et al. (13) due to some ambiguous structural features but also immunological properties. These concerned the terminal part of the sugar polysaccharide as well as the structure of the biosynthetic repeating unit. The need for this revision was based on two important observations. First, the original model was unable to explain the cross-reactivity of pnLTA with anti-Forssman antigen antibodies. Second, the originally defined trisaccharide-diacylglycerol lipid anchor, (→6)-β-d-Glcp-(1→3)-β-2-acetamido-4-amino-2,4,6-trideoxygalactose (AATGalp)-(1→3)-α-d-Glcp(1→3)-acyl2Gro (12), has never been identified in S. pneumoniae cell wall lipid extracts (14). Due to this fact and to mass spectrometric analysis, a new interpretation of the pnLTA structure was deduced. Only (→3)-α-d-Glcp-(1→3)-acyl2Gro (a common pneumococcal cell wall glycolipid (14, 15)) was defined as the lipid anchor. This new interpretation resulted in a “shift” of the pseudopentameric repeating unit, now starting with AATGalp and ending with 6-O-P-Cho-substituted α-d-GalpNAc. This revised model was further substantiated by the fact that it now displayed a terminal α-d-GalpNAc-(1→3)-β-d-GalpNAc-(1→) disaccharide, representing a structural feature that is able to explain the Forssman antigen properties of pnLTA (12, 16). Additionally, using an improved isolation procedure to obtain pure pnLTA followed by sophisticated NMR analysis, it was shown in 2006 that the Rib-ol-5-P can be substituted with α-d-GalpNAc and d-Ala in a strain-specific manner (17). The current structural model for pnLTA, complemented with these proposed substituents of Rib-ol-5-P, is shown in Fig. 1.

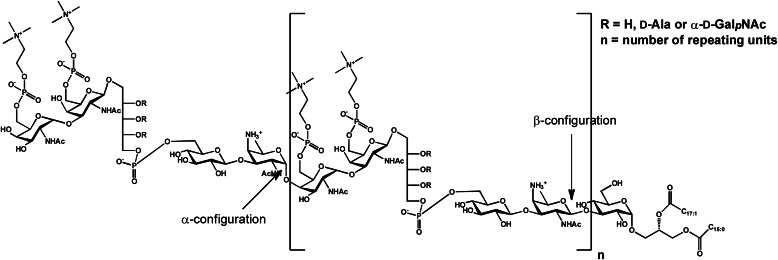

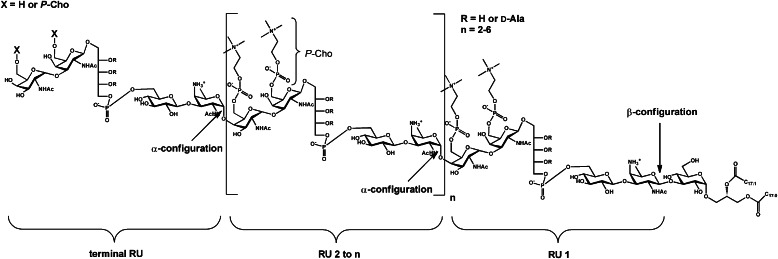

FIGURE 1.

Current structural model for pneumococcal LTA (13, 17). One RU contains AATGalp, Glcp, Rib-ol-5-P, and two GalpNAc, both substituted in position O-6 with P-Cho. All RUs are β-1-linked, only the terminal is α-1-linked, and the RU chain is bound to a Glcp-DAG. The hydroxyl groups of Rib-ol-5-P can be substituted in non-stoichiometric amounts by d-Ala and α-d-GalpNAc, respectively.

Despite this progress, the current pnLTA structural model still remained in part controversial. For instance, the β-configurated AATGal in this model was placed within the repeating unit, whereas earlier studies (12, 17) determined α-AATGal to be within these repeats. Furthermore, the two techniques MALDI-TOF MS (13) and NMR (17) led to totally different chain length of pnLTA for identical or at least closely related strains. NMR measurements in D2O revealed 2–3 RU for strain R6 and 2 RU for strain TIGR4Δcps (17). In contrast, by MALDI-TOF MS, a dominant chain length of 5–8 RU was detected for many strains. In detail, for pneumococcal strain R6, 5–7 repeats were observed, and for TIGR4 (the encapsulated serotype 4 wild type of TIGR4Δcps), mainly 6 and 7 repeats were observed (13).

In general, usage of 1H NMR for structural analysis of glycolipids and their RU requires specific comments in order to validate the data obtained and in order to obtain a reliable amount of the RU. The NMR approach can be prone to misinterpretations because glycolipids, like LTA, show a tendency to form huge aggregates and micelles in water (18), thus leading to false integration values for their 1H signals. Therefore, a reliable analysis of the number of RU, reflecting the size of the LTA molecule, can in many cases only be obtained by either mass spectrometry or, as in the new NMR-based methodology presented here, with data and integration values obtained from 1H NMR spectra of O-deacylated (hydrazine-treated) and non-aggregated LTA molecules. Such O-deacylated pnLTA polysaccharides do not form aggregates in water, and hence values for their 1H integral resonances are considered to be reliable. One exception is the integration of 1H NMR signals obtained from type I LTA (originally established for LTA of Staphylococcus aureus (19)). Here, our analysis of LTA isolated from S. aureus strain SA113Δlgt by NMR and MS led to comparable results for the number of RU (data not shown). In addition, the resolution of signals in O-deacylated pnLTA is significantly increased, this way further corroborating the correct structural assignment.

From all of these considerations, we finally came to the conclusion that the actual structural model of pnLTA (13) (Fig. 1) again required a careful reinvestigation. For this purpose, we combined data from pnLTA obtained by two different and independent analytical methodologies (NMR and MS). We especially focused on the analysis of structural details in the RU, the terminal disaccharide, and the position and linkage of the putative substituents of the Rib-ol-5-P within the RU. The structural controversy of former models could be clarified in a new and revised structural model, which we consider also to be in agreement with a recently proposed common biosynthetic pathway of both pneumococcal teichoic acids (20).

Besides analytical investigations, we also describe here the immunostimulatory properties of pnLTA in hMNCs, independently of those caused by TLR2 activation. During the last few years, various bacterial structures (mostly derived from cell wall components) have been proposed to be specific ligands for the TLR2 receptor (21), and for many years LTA was one of these. The importance of LTA in the bacterial stimulation of the innate immune system has been overestimated when it was considered to represent the “endotoxin of Gram-positive bacteria” (22). A major contribution to clarify the immunostimulatory potency of LTA has been made by Stoll et al. (23), who constructed a Δlgt mutant of an S. aureus strain (SA113). This mutant was deficient in the lipidation of the prelipoproteins and showed attenuation in immune activation and growth. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that LPs are the predominant TLR2 stimuli in LTA preparations of S. aureus and not the LTA itself (24). The mechanism of this immune activation could be further specified; the signaling induced by triacylated LPs occurs via a TLR2/TLR1 heterodimer (proven with a hTLR2-hTLR1-Pam3CSK4 co-crystal (25)), whereas diacylated LPs signal via a TLR2/TLR6 heterodimer (as shown by solving a mTLR2-mTLR6-Pam2CSK4 co-crystal (26)). Furthermore, also LPs that signal via both TLR2/TLR1 and TLR2/TLR6 heterodimer have been described in murine cells (27). Here, we avoided the TLR2 activity originating from contaminating LPs/lipopeptides by using a mutant strain of S. pneumoniae without biologically functional LPs (strain D39ΔcpsΔlgt), which also lacked the capsular polysaccharide. Because we also isolated LTA from a Δlgt mutant of S. aureus strain SA113 (23) and compared it with the purified pnLTA described here, we could identify, besides the known structural differences, strong biological variations of these LTA preparations with respect to their proinflammatory potencies by monitoring the release of proinflammatory cytokines in vitro (IL-6 in hMNCs).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains and Growth

S. pneumoniae strains D39Δcps (28), D39ΔcpsΔlgt (nonencapsulated mutants of serotype 2 wild-type D39), and TIGR4Δcps (FP23; nonencapsulated mutant of serotype 4 wild-type TIGR4, a kind gift of F. Iannelli (Siena, Italy)) were grown in 5-liter batches (5 × 1 liter) in THY medium (pH 7.4 (condition A); for the cultivation under mild acidic conditions, THY medium is set to pH 6.5 using a sodium chloride solution (condition B)) to late logarithmic phase (A600 ≈ 1) and then harvested by centrifugation (8000 × g, 10 min, room temperature). After washing with citric buffer (50 mm, pH 4.7), cells were resuspended in citric buffer containing 4% SDS and incubated for 20 min at 100 °C. Cells were then stored at −80 °C overnight and lyophilized subsequently. Until extraction of their pnLTAs, pneumococcal cells were frozen at −20 °C.

S. aureus strain SA113Δlgt (23) (kindly provided by F. Götz (Tübingen, Germany)) was grown in Difco Antibiotic Medium 3 (BD Biosciences) until late logarithmic phase (A578 = 0.9–1.0) was reached and then harvested by centrifugation (3000 × g, 15 min, 4 °C). Cells were resuspended in citric buffer (50 mm, pH 4.7) containing 4% SDS and incubated for 30 min at 100 °C. Staphylococcal cells were then immediately used for LTA extraction.

Generation of the Δlgt Mutant in S. pneumoniae D39Δcps

S. pneumoniae D39ΔcpsΔlgt was generated by insertion deletion mutagenesis. Genomic DNA of strain R6Δlgt (29) was used as template in a PCR to amplify a 1940-bp fragment containing the lgt gene region interrupted by the ermB gene using primer pair lgt1fw (5′-GCCGTGCAGCTACCAGTCG-3′) and lgt7rev (5′-CATCGATGACACGACCAAGC-3′). The PCR product was cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega, Madison, WI), and S. pneumoniae D39Δcps was transformed with the generated plasmid construct in the presence of competence-stimulating peptide-1, as described previously (30). S. pneumoniae D39ΔcpsΔlgt was cultivated in THY medium supplemented with 5 μg/ml erythromycin. Gene knock-out of the Δlgt mutant was verified by a colony PCR procedure using template DNA isolated by heat lysis (96 °C for 8 min) from pneumococci in the exponential growth phase.

Extraction and Isolation of LTA

LTA purification was performed basically as described elsewhere (19) but with several modifications in detail. Pneumococcal cells were resuspended in distilled water prior to extraction, thus restoring the concentration of citric buffer (50 mm, pH 4.7) and SDS (4%). Cells were disrupted in a cell homogenizer (Vibrogen Cell Mill VI 6, Edmund Bühler GmbH) with 0.1-mm glass beads (Carl Roth GmbH). Afterward, glass beads were removed by centrifugation (2000 × g, 10 min, room temperature) and washed twice with citric buffer. To the combined supernatants SDS (20% solution) was added to obtain a final concentration of 4%. This solution was incubated for 30 min at 100 °C and centrifuged (30,000 × g, 15 min, 4 °C) subsequently. The pellet was washed four times with citric buffer, and the supernatants were combined and lyophilized. The resulting solid was washed SDS-free with ethanol (10,650 × g, 20 min, 20 °C). The resulting sediment was resuspended in citric buffer and extracted with an equal volume of butan-1-ol (Merck) for 30 min at room temperature under vigorous stirring. Phases were separated at 4000 × g and 4 °C for 10 min. The aqueous phase was removed, and the extraction procedure was repeated twice. The combined LTA-containing water phases were lyophilized prior to dialysis for 5 days at 4 °C against 50 mm ammonium acetate buffer (pH 4.7; 3.5 kDa cut-off; buffer change usually every 24 h). A final lyophilization leads to the crude LTA, which is further purified by hydrophobic interaction chromatography performed on a HiPrep Octyl-Sepharose column (GE Healthcare; 16 × 100 mm, bed volume 20 ml) (31). For this purpose, the crude material was dissolved in as little starting buffer (15% propan-1-ol (Merck) in 0.1 m ammonium acetate (pH 4.7)) as possible and centrifuged (13,000 × g, 5 min, room temperature) and the obtained supernatant was subjected to hydrophobic interaction chromatography using a linear gradient from 15 to 60% propan-1-ol in 0.1 m ammonium acetate (pH 4.7). LTA-containing fractions were identified by a photometric phosphate test (32), and phosphate-containing fractions were combined, lyophilized, and repeatedly washed with water upon freeze-drying to remove residual buffer (yields of pnLTA from a 5-liter batch: strain D39Δcps, 6 mg (growth condition A) and 7 mg (B); strain D39ΔcpsΔlgt, 15 mg (B); and strain TIGR4Δcps, 13 mg (A) and 14 mg (B)). For immunological testing, in some cases, aliquots of pnLTA were treated with 1% H2O2 at 37 °C for 24 h to inactivate residual contaminating LPs by oxidation as described (33).

NMR Spectroscopy

Deuterated solvents were purchased from Deutero GmbH (Kastellaun, Germany). NMR spectroscopic measurements were performed in D2O or deuterated 25 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.5; to suppress fast de-alanylation) at 300 K on a Bruker AvanceIII 700 MHz (equipped with an inverse 5-mm quadruple-resonance Z-Grad cryoprobe or with an inverse 1.7-mm triple-resonance Z-Grad microcryoprobe). Acetone was used as an external standard for calibration of 1H (δH 2.225) and 13C (δC 31.08) NMR spectra (34), and 85% of phosphoric acid was used as an external standard for calibration of 31P NMR spectra (δP 0.00). All data were acquired and processed by using Bruker TOPSPIN version 3.0. 1H NMR assignments were confirmed by two-dimensional 1H,1H COSY and TOCSY experiments, and 13C NMR assignments were indicated by two-dimensional 1H,13C HSQC, based on the 1H NMR assignments. Interresidue connectivity and further evidence for 13C assignment were obtained from two-dimensional 1H,13C heteronuclear multiple bond correlation and 1H,13C HSQC-TOCSY. Connectivity of phosphate groups was assigned by two-dimensional 1H,31P HMQC and 1H,31P HMQC-TOCSY.

Electrospray Ionization Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry

Electrospray ionization Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (ESI-FT-ICR-MS) was performed on a 7-tesla APEX Qe instrument (Bruker Daltonics). For the negative ion mode, the samples were dissolved in a water/propan-2-ol/triethylamine/acetic acid mixture (50:50:0.006:0.002, v/v/v/v). The samples were sprayed at a flow rate of 2 μl/min. Capillary entrance voltage was set to 3.8 kV, and dry gas temperature was set to 200 °C. To optimize the signal intensity of the molecular peaks, the collision voltage was slightly increased (in the range of 5–15 V). Mass spectra were recorded in broad band mode, and mass scale was calibrated externally with glycolipids of known structure. The spectra were charge-deconvoluted, and the mass numbers given refer to the monoisotopic mass of the neutral molecules.

Hydrazine Treatment of pnLTA

pnLTA preparations were dissolved 5 μg/μl in anhydrous hydrazine (N2H4; ICN Biomedicals) and then incubated for 1 h at 37 °C and 100 rpm (orbital shaker). The reaction was quenched by adding the same volume of acetone and dried under a stream of nitrogen. The latter step was repeated twice, and the crude O-deacylated pnLTAs were purified by gel permeation chromatography on a column using P-10 Biogel (45–90 μm; Bio-Rad) (column size, 1.5 × 120 cm; buffer, 150 mm ammonium acetate (pH 4.7)) or Toyopearl TSK-40S (Tosoh Bioscience) (column size, 2.5 × 50 cm; buffer, 50 mm pyridine/acetic acid/water (8/20/2000, v/v/v)). Best purity was obtained when the P-10 column and then the TSK-40S column were used subsequently for the same O-deacylated pnLTA.

Cell-based Assays

HMNCs were isolated from blood of healthy adult donors (containing sodium citrate as an anticoagulant) by Ficoll-Isopaque density gradient centrifugation (35). Isolated hMNCs were washed with PBS and cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% autologous human serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany). HMNCs (1 × 106/ml) were stimulated in triplicates with different concentrations of the indicated stimuli (LPS from Salmonella enterica sv. Friedenau was a kind gift of Prof. H. Brade, Research Center Borstel). After 20 h, supernatants were collected, and the content of IL-6 was quantified by ELISA (Invitrogen). Experiments with transiently transfected HEK293 cells were performed with modifications based on a previous publication (36). Briefly, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with plasmids coding for the indicated innate immune receptors. After 24 h of transfection, cells were washed and incubated with different concentrations of the indicated stimuli (synthetic lipoprotein FSL-1 was purchased from EMC microcollections). IL-8 secretion was measured 18 h after incubation as a marker of HEK293 cell activation by collecting the supernatants and quantifying the IL-8 content using a commercial ELISA (Invitrogen). As a negative control, medium without a stimulus was used. Assays were performed in triplicates.

Antibodies, Forssman Glycosphingolipid (Forssman GSL), and Serological Analysis

Investigation of the Forssman antigen properties of pnLTA preparations was performed by ELISA. Therefore, 96-well Nunc Maxisorp® plates were coated overnight at 4 °C with the indicated concentrations (as duplicates) of pnLTA preparations (in 100 μl of 100 mm citric buffer (pH 4.7)). As a positive control, different concentrations of Forssman GSL (prepared from sheep blood cells following standard procedure (37–40)) were coated under same conditions using 100 μl of methanol. The wells were then washed three times with PBS and blocked for 1 h at 37 °C with PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (Carl Roth GmbH). After washing with PBS, 100 μl per well of primary antibody (monoclonal rat IgM (clone IIC2) anti-Forssman GSL antibody; produced as described previously by Bethke et al. (41, 42); specificity of this antibody has been shown (43)) diluted 1:50 in PBS were added, and the plate was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The wells were washed, 100 μl of secondary antibody (goat anti-rat IgM (HRP conjugate); Lot 03221201; Enzo Life Sciences) diluted 1:2500 in PBS were added to the wells, and the plate was incubated again for 1 h at 37 °C. After washing, 100 μl of ABTS (Roche Applied Science) were added per well and, after 20 and 30 min of incubation at 37 °C, the color reaction was measured at 405 nm using a Fluostar Fluoreader (BMG Labtech). Values were reported subtracting the absorbance measured for uncoated wells from the absorbance of LTA-coated wells.

RESULTS

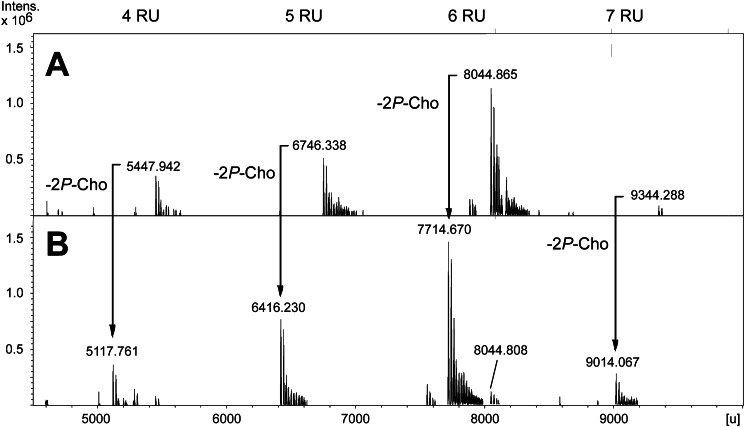

Structural Analysis of Native Pneumococcal LTA

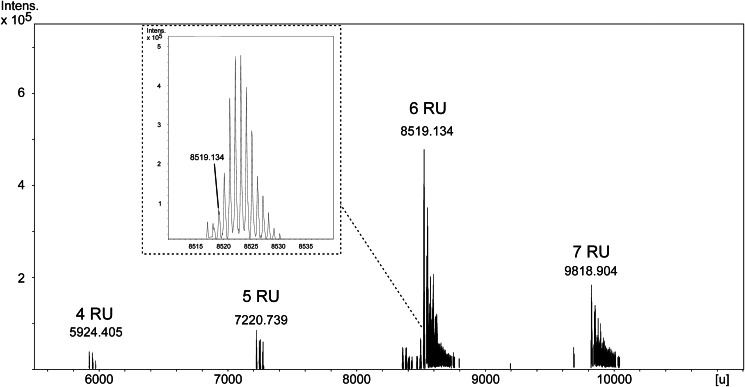

To ensure the comparability of our analytical data with the most recent reports (13, 17), we used the representative strains D39Δcps(Δlgt) and TIGR4Δcps for isolation of their pnLTA. Bacteria were grown under mild basic (pH 7.4; condition A) or mild acidic (pH 6.5; condition B) conditions. Butanol extraction of pneumococcal cells and subsequent LTA purification by hydrophobic interaction chromatography was performed following the procedure of Morath et al. (19). To optimize the yield and purity of pnLTA, several details have been modified (for further details, see “Experimental Procedures”). ESI-FT-ICR-MS analysis confirmed the molecular composition of pnLTA as described by Seo et al. (13). The ESI spectrum of pnLTA isolated from strain D39Δcps (growth condition A) is shown in Fig. 2. The groups of isotopic mass peaks around the neutral monoisotopic masses 8519,134 and 9818,904 units represent pnLTA containing 6 or 7 RU (n in Fig. 1 is 5 or 6), respectively, with (→3)-α-d-Glcp-(1→3)-DAG(16:0,16:1) as the lipid anchor. These masses are in good agreement with the respective calculated masses, which are given in Table 1, considering different numbers of repeating units, the presence or absence of fatty acids, and different amounts of P-Cho residues. Further mass peak groups are caused by microheterogeneity in the fatty acid composition as well as multiple sodium and potassium adduct ion formation. In minor peaks, the loss of one P-Cho residue was also detectable. The appropriate ESI spectrum of TIGR4Δcps pnLTA showed a more complex composition due to the presence of additional alanine substituents at the Rib-ol-5-P and a more significant loss of one P-Cho residue (supplemental Fig. S1 and Table S1). However, with the exception of its degree in alanylation of the pnLTA and the pattern of fatty acid combinations, this strain revealed the same structure (4–6 RU) as observed before for strain D39Δcps. NMR measurements of these pnLTA preparations led to 1H NMR spectra comparable with those of Draing et al. (17) (data not shown). Integration of the 1H NMR signals revealed an average length of 3 RU in the pnLTA, which is almost consistent with the former NMR results. By contrast, these data were inconsistent with our own MS data. This contradiction of results from NMR and MS analysis reflects exactly the above mentioned, existing inconsistent results in the literature (12, 13). Reliable values for the number of RU (based on the data obtained by integration of 1H NMR spectra) are difficult to obtain due to the known formation of rather big micelles when LTA is dissolved in aqueous solutions (18). In order to overcome this methodological problem, we O-deacylated the hydrophobic interaction chromatography-purified pnLTA by mild hydrazine treatment. By doing so, all ester-bound substituents (fatty acids, d-Ala) are removed without cleaving phosphodiester bonds in the RUs or altering any other structural detail in the pnLTA molecule. Thus, the integrals obtained from the 1H NMR spectra become suitable for the correct interpretation of 1H values, because aggregate formation was not observed in the O-deacylated pnLTA.

FIGURE 2.

Section (5500–11,000 units (u)) of the ESI-FT-ICR-MS spectrum (charge deconvoluted) of pnLTA isolated from strain D39Δcps (growth condition A). The inset shows the group of isotopic mass peaks around the neutral monoisotopic mass peak for pnLTA with (→3)-α-d-Glcp-(1→3)-DAG(16:0,16:1) as the lipid anchor + 6 RU (calculated: 8519.203 units). The low intensity peak with Δm = −2 units corresponds to a molecule carrying a fatty acid with one additional double bond.

TABLE 1.

Predicted masses of pneumococcal LTA considering different numbers of RU, the presence or absence of fatty acids, and different amounts of P-Cho residues

The mass of native lipid anchor was calculated for α-d-Glcp-(1→3)-acyl2Gro with fatty acid combination 16:0, 16:1 (most abundant combination in pnLTA of strain D39Δcps). One RU is equivalent to 6-O-P-Cho-α-d-GalpNAc-(1→3)-6-O-P-Cho-β-d-GalpNAc-(1→1)-Rib-ol-5-P-(O→6)-β-d-Glcp-(1→3)-AATGalp.

| No. of RU | Predicted molecular masses of S. pneumoniae LTA |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native |

Hydrazine-treated |

|||

| No P-Cho missing | 2 P-Cho missing | No P-Cho missing | 2 P-Cho missing | |

| units | ||||

| 0 | 728.541 | 254.097 | ||

| 1 | 2026.984 | 1696.873 | 1552.541 | 1222.430 |

| 2 | 3325.428 | 2995.317 | 2850.984 | 2520.874 |

| 3 | 4623.872 | 4293.761 | 4149.428 | 3819.317 |

| 4 | 5922.316 | 5592.205 | 5447.872 | 5117.761 |

| 5 | 7220.760 | 6890.649 | 6746.316 | 6416.205 |

| 6 | 8519.203 | 8189.093 | 8044.760 | 7714.649 |

| 7 | 9817.647 | 9487.536 | 9343.204 | 9013.093 |

Structural Analysis of Hydrazine-treated Pneumococcal LTA

The structural investigation of O-deacylated pnLTA has two major advantages. First, less complex MS data are obtained because the microheterogeneity of pnLTA is extremely reduced due to the lack of fatty acids (differing in number of methylene groups) and d-alanine residues. Second, 1H NMR spectra show a significant higher resolution due to the absence of aggregates. For example, in 1H,13C HSQC NMR experiments with native pnLTA, no signals of the (→3)-α-d-Glcp-(1→) of the lipid anchor could be detected. By contrast, the identical experiment performed with hydrazine-treated (O-deacylated) pnLTA (pnLTAN2H4) allows the assignment of signals for this α-d-Glcp (A in Fig. 4) as well as for most signals of all other minor represented sugars. The MS analysis of pnLTAN2H4 from strain D39Δcps (growth condition B) as well as D39ΔcpsΔlgt (growth condition B) revealed the same structure as found for strain D39Δcps using growth condition A with only minor differences in the proportional distribution of the chain length (data not shown).

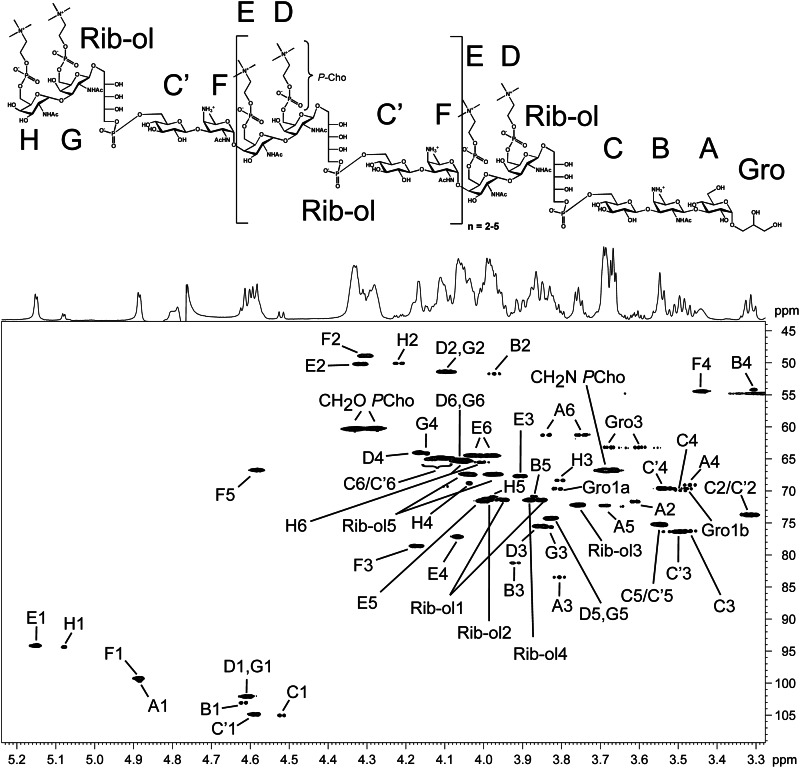

FIGURE 4.

Section (δH 5.24–3.28; δC 109–43.5) of the 1H,13C HSQC NMR spectrum (700 MHz) obtained from hydrazine-treated pnLTA of strain D39ΔcpsΔlgt (growth condition B), including structure (top) and assignment of signals (bottom).

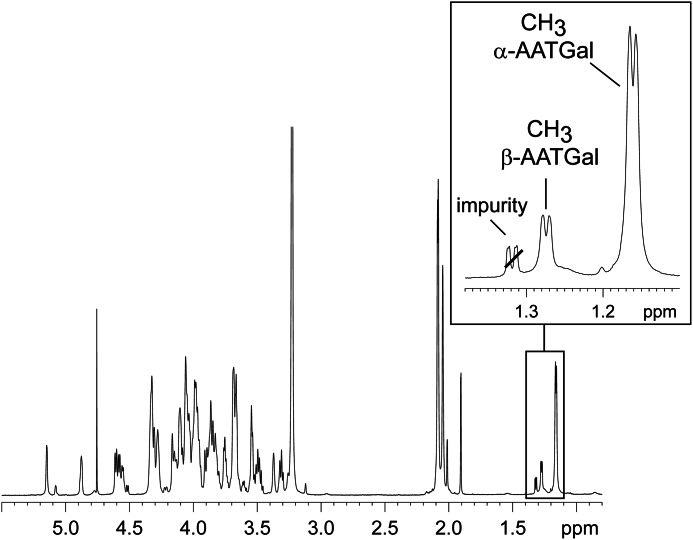

The structural investigation of pnLTAN2H4 by NMR is explained in the following using strain D39Δcps(Δlgt). In Fig. 3, the 1H NMR of this pnLTAN2H4 is depicted as a representative example. As indicated in the magnified region, in the absence of fatty acids, the methyl groups of AATGalp (CH3 group in the C-6-position of a 6-deoxy sugar) could be clearly distinguished for both α- and β-AATGalp residues, whereas the signal for the latter one could not be detected in 1H NMR spectra of native pnLTA. This important structural detail appeared in the same ppm region as the methylene groups of fatty acids, thus hampering a correct assignment and the quantification. The doublet at δH 1.16 (3J5,6 6.4 Hz) could be assigned to the methyl group of α-AATGalp, and that at δH 1.27 (3J5,6 6.4 Hz) could be assigned to the β-AATGalp. Integration revealed a ratio of α/β of ∼5:1, giving strong evidence that the α-configuration of AATGalp must be present within the repeating units, representing a structural detail that is in disagreement with the current structural model of pnLTA (13) (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 3.

Section (δH 5.5–0.8) of the 1H NMR of hydrazine-treated pnLTA of strain D39Δcps (growth condition A). The δH 1.4–1.1 region (inset) shows that both C-6 methyl groups of α- and β-AATGal can be clearly distinguished.

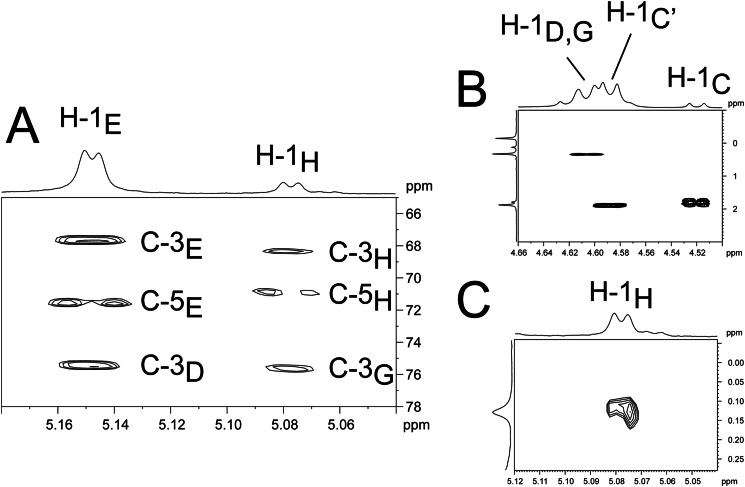

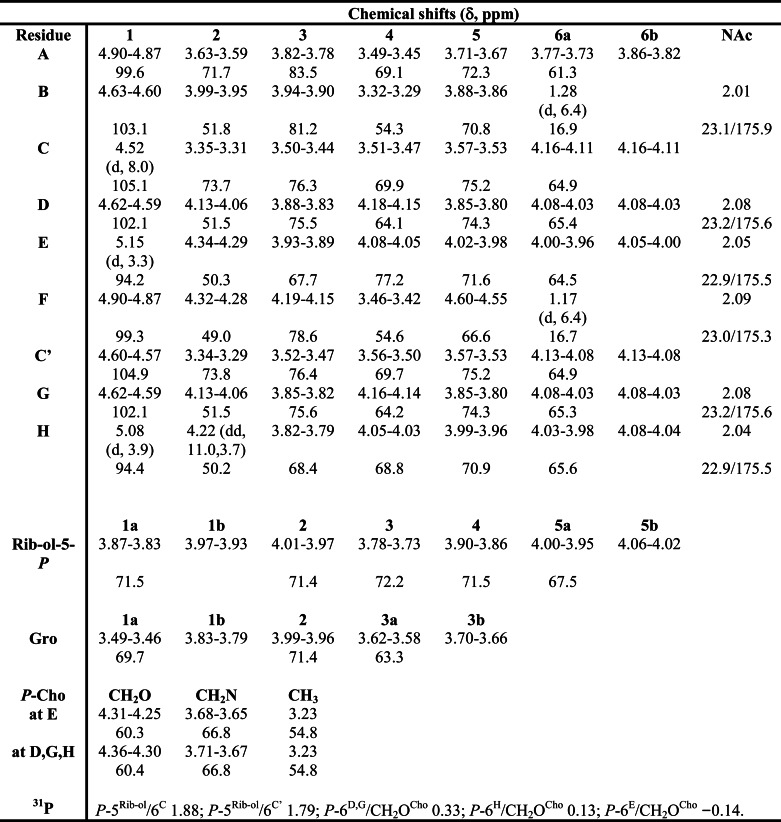

In Fig. 4, a section of the 1H,13C HSQC NMR of pnLTAN2H4 of strain D39ΔcpsΔlgt (growth condition B) is shown, including the assignment of signals and the structure we deduced from our results. The detailed chemical shifts are given in Table 2. All signals, including those not related to sugars in the RUs (residues A, B, C, G, and H), could be assigned unequivocally and completely, which was not possible using NMR spectra obtained from the native pnLTA. As indicated, we were able to assign the doublet at δH 5.08 (3J1,2 3.9 Hz) with δC 94.4 to the anomeric proton and carbon of the terminal 6-O-P-Cho-α-d-GalpNAc (H in Fig. 4). This signal has formerly been assigned to the anomeric proton and carbon of an α-d-GalpNAc substituent at the phosphoribitol (17). In Fig. 5A, a section of the 1H,13C heteronuclear multiple bond correlation NMR is depicted. The different cross-correlations for the anomeric protons of the 6-O-P-Cho-α-d-GalpNAc residues within the RU (E) and the terminal one (H) are shown. For both protons, a clear cross-correlation to signals from the C-3 of the respective neighboring 6-O-P-Cho-β-d-GalpNAc (δC 75.6 (C-3D) or δC 75.5 (C-3G)) was present, indicating that both α-d-GalpNAc residues were indeed (1→3)-linked to a β-d-GalpNAc residue. Additionally, we could proof the 6-O-P-Cho substitution in H by a 1H,31P HMQC-TOCSY experiment. A mixing time of 180 ms was necessary for the observation of a significant cross-signal of H-1H (δH 5.08) and the 31P NMR signal at δP 0.11 (Fig. 5B). In the same way, cross-signals between other phosphorous signals and their respective anomeric protons could be observed (Fig. 5C). The corresponding one-dimensional 31P NMR spectrum, including the assignment of signals, is shown in Fig. 7B. Furthermore, in combining our NMR and MS data, we obtained no evidence for a glycosyl substitution of the Rib-ol-5-P in the pnLTA preparations of strains used in this work (D39Δcps(Δlgt) or TIGR4Δcps, respectively).

TABLE 2.

1H and 13C chemical shift data of hydrazine-treated LTA of S. pneumoniae strain D39ΔcpsΔlgt (growth condition B)

All reported values are based on spectra acquired at 300 K in D2O and are relative to an external acetone calibration (δH 2.225; δC 31.08). For structure and nomenclature of residues, see Fig. 4.

FIGURE 5.

Sections of different two-dimensional NMR spectra of hydrazine-treated pnLTA of strain D39ΔcpsΔlgt (growth condition B). A, section (δH 5.18–5.04; δC 78–65) of the 1H,13C heteronuclear multiple bond correlation NMR. B, section (δH 4.66–4.50; δP 3-(−1)); C, section (δH 5.12–5.04; δP 0.28-(−0.06)) of the 1H,31P HMQC-TOCSY NMR. For structure and nomenclature of the residues see Fig. 4.

FIGURE 7.

Sections (δP 4-(−2)) of the 31P NMR of hydrazine-treated pnLTA of strain TIGR4Δcps (growth condition B; terminus without P-Cho substitution) (A) and strain D39ΔcpsΔlgt (growth condition B; terminus with P-Cho substitution) (B), including assignment of signals. For complete structure and nomenclature of residues, see Fig. 4.

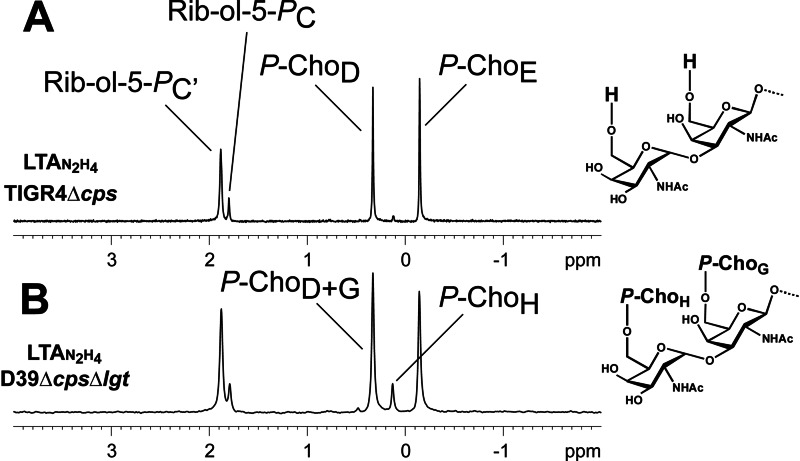

Pneumococcal LTA of Strain TIGR4Δcps Possesses a Different Terminus under Mild Acidic Growth Conditions

We investigated the structure of pnLTA of S. pneumoniae strain TIGR4Δcps in the same way as described above for strain D39 Δcps(Δlgt). As mentioned above, using mild basic growth conditions (growth condition A), this strain produces a pnLTA with a structure that is more heterogenic than but comparable with those observed using strain D39. Interestingly, under mild acidic conditions (growth condition B), a pnLTA is formed that lacks exactly two P-Cho residues, representing the lowest amount of P-Cho substituents when compared with all other pnLTA preparations isolated in this work. In order to demonstrate this structural feature in more detail, a ESI spectrum of this special pnLTAN2H4 preparation is shown in Fig. 6B and compared with the MS spectrum of pnLTAN2H4 of strain D39ΔcpsΔlgt (obtained using growth condition B; Fig. 6A). The respective 31P NMR spectra are depicted in Fig. 7. The almost complete absence of the signal for P-ChoH at δP 0.13 in the pnLTAN2H4 of strain TIGR4Δcps (Fig. 7A) suggests that in this strain, when grown under these conditions, the terminal α-d-GalpNAc is not substituted with a P-Cho in position O-6. Furthermore, the ratio between the signals at δP 0.33 (P-ChoD) and δP −0.14 (P-ChoE) in this case was found to be 5:5 instead of 6:5 (P-ChoD+G versus P-ChoE), as found for pnLTA of strain D39 ΔcpsΔlgt (Fig. 7B). From these data, we concluded that in this particular pnLTA preparation, the Forssman antigen terminus (G and H in Fig. 4) corresponds to the unmodified Forssman disaccharide α-d-GalpNAc-(1→3)-β-d-GalpNAc-(1→). We further validated the correctness of this interpretation by NMR signals observed for the non P-Cho-substituted sugars G and H, which indeed exactly matched (with the exception of H-1G) with the chemical shift values obtained for a known synthetic precursor of the Forssman antigen (para-nitrophenyl-Forssman antigen, pNP-Fa) (44). A section of the 1H,13C HSQC NMR of this pnLTAN2H4 preparation is shown in supplemental Fig. S2. The chemical shifts for unsubstituted sugars G and H are listed in Table 3 in comparison with the data obtained from literature for pNP-Fa and the shifts for pnLTAN2H4 of strain D39 ΔcpsΔlgt (taken from Table 2). The assignment of all signals for the pnLTAN2H4 preparation of strain TIGR4Δcps (growth condition B) is given in supplemental Table S2. The anomeric proton (H-1H) of the non-substituted α-d-GalpNAc-(1→3) is slightly but significantly shifted from δH 5.08 to δH 5.07, as it is the case in the reference compound pNP-Fa. As expected, the chemical shifts for protons and carbons 1–3 are in all three compounds almost comparable, whereas the shifts for protons and carbons 4–6 are deviating for the pnLTAN2H4 of strain D39ΔcpsΔlgt due to the P-Cho substitution in the O-6-position.

FIGURE 6.

Sections (4500–10,000 units) of ESI-FT-ICR-MS spectra (charge-deconvoluted) of hydrazine-treated pnLTA of strain D39ΔcpsΔlgt (growth condition B) (A) and strain TIGR4Δcps (growth condition B) (B). For structure and nomenclature of residues see Fig. 4.

TABLE 3.

1H and 13C chemical shift data for the Forssman disaccharide terminus in hydrazine-treated LTA of S. pneumoniae strain D39ΔcpsΔlgt or TIGR4Δcps (both growth condition B) in comparison with data for pNP-Fa (44)

| Position | Chemical shifts (δ) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pnLTAN2H4 D39ΔcpsΔlgt (B)a |

pnLTAN2H4 TIGR4Δcps (B)b |

pNP-Fa (44) |

||||

| δH | δC | δH | δC | δH | δC | |

| ppm | ppm | ppm | ||||

| α-GalNAc (H) | ||||||

| 1 | 5.08 | 94.4 | 5.07 | 94.2 | 5.07 | 94.5 |

| 2 | 4.22 | 50.2 | 4.23–4.20 | 50.2 | 4.22 | 50.3 |

| 3 | 3.82–3.79 | 68.4 | 3.80–3.77 | 68.5 | 3.81 | 68.6 |

| 4 | 4.05–4.03 | 68.8 | 4.02–4.00 | 69.2 | 4.00 | 69.2 |

| 5 | 3.99–3.96 | 70.9 | 3.85–3.82 | 72.2 | 3.87 | 72.2 |

| 6a | 4.03–3.98 | 65.6 | 3.78–3.76 | 61.7 | 3.77 | 61.8 |

| 6b | 4.08–4.04 | 3.78–3.76 | 3.77 | |||

| NAc | 2.04 | 22.9 | 2.04 | 22.8 | 2.07 | 23.1 |

| β-GalNAc (G) | ||||||

| 1 | 4.62–4.59 | 102.1 | 4.58 | 102.1 | 4.73 | 103.7 |

| 2 | 4.13–4.06 | 51.5 | 4.08–4.06 | 51.6 | 4.11 | 51.8 |

| 3 | 3.85–3.82 | 75.6 | 3.82–3.79 | 75.6 | 3.83 | 75.6 |

| 4 | 4.16–4.14 | 64.2 | 4.12–4.10 | 64.4 | 4.11 | 64.5 |

| 5 | 3.85–3.80 | 74.3 | 3.67–3.63 | 75.9 | 3.65 | 75.8 |

| 6a | 4.08–4.03 | 65.3 | 3.77–3.74 | 61.9 | 3.81 | 62.0 |

| 6b | 4.08–4.03 | 3.85–3.80 | 3.76 | |||

| NAc | 2.08 | 23.2 | 2.07 | 23.1 | 2.04 | 22.9 |

a Data taken from Table 2.

b Full assignment of signals in supplemental Table S2.

It must be outlined in this respect that the described occurrence of the not P-Cho-substituted Forssman antigen terminus is not always quantitative. We also observed a preparation of pnLTAN2H4 using strain TIGR4Δcps (growth condition B) where a mixture was present, in which either G and H were both P-Cho-substituted, both were unsubstituted, or only one P-Cho was missing (ESI spectrum in supplemental Fig. S3).

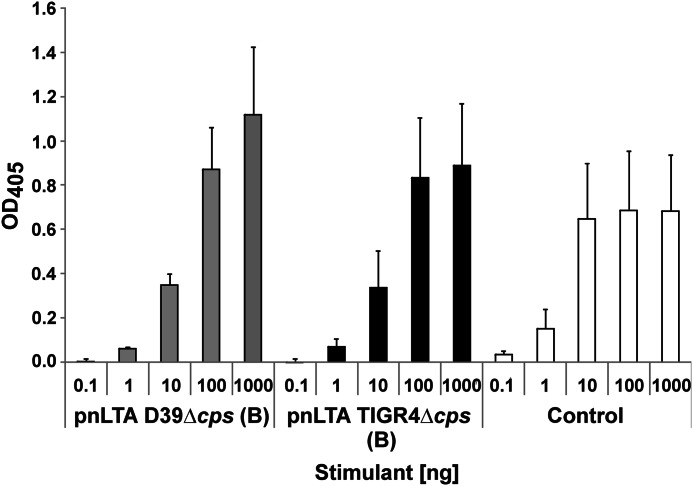

Modification of the Forssman Antigen Terminus with P-Cho Residues Exerts No Influence on Antibody Detection

We further investigated the influence of the P-Cho-O-6 substitution of the Forssman disaccharide within the pnLTA with regard to the recognition by a monoclonal IgM-antibody directed against the Forssman GSL. pnLTA from strain D39Δcps (growth condition B; terminus with P-Cho substitution) as well as from strain TIGR4Δcps (growth condition B; terminus without P-Cho substitution) was used. The ELISA-based results revealed no significant differences in antibody-specific binding (Fig. 8), demonstrating that changes in P-Cho-O-6 substitution did not influence on the anti-Forssman GSL antibody reactivity.

FIGURE 8.

Recognition of pnLTA by an anti-Forssman GSL antibody. Various concentrations of pnLTA from strain D39Δcps (growth condition B; terminus with P-Cho substitution) as well as from strain TIGR4Δcps (growth condition B; terminus without P-Cho substitution) and Forssman GSL as positive control were used. As antibodies, a monoclonal rat IgM (clone IIC2) anti-Forssman GSL antibody (37–40) and a goat anti-rat IgM (HRP conjugate) as a secondary antibody were applied. The optical density of the resulting color reaction, initialized by ABTS, was measured at 405 nm after 20 min. Values were reported, subtracting the absorbance measured for uncoated wells from the absorbance of LTA-coated wells. Data are shown as means ± S.D. (error bars) of three independent experiments performed as duplicates.

Immunostimulatory Properties of Pneumococcal LTA

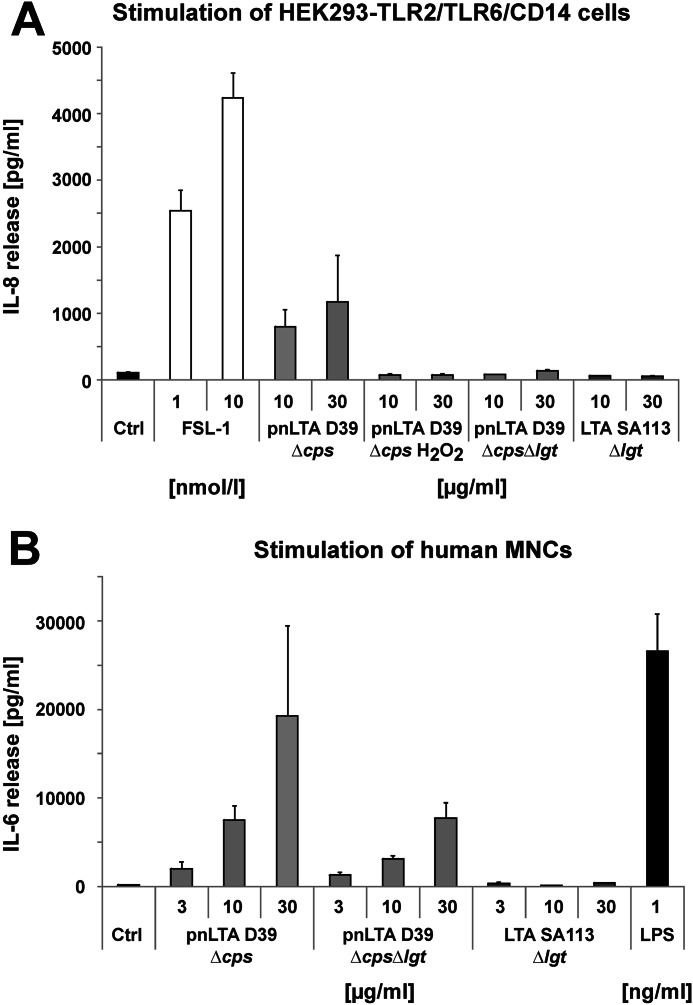

We tested the TLR2 activity of our LTA preparation isolated from S. pneumoniae strain D39ΔcpsΔlgt and compared it with the preparations isolated from strain D39Δcps as well as the LTA of S. aureus strain SA113Δlgt (Fig. 9A). To use a test system that is very sensitive for diacylated LPs, we transiently transfected HEK293 cells with TLR2 together with TLR6 and CD14. However, because endogenous TLR1 is expressed in HEK293 cells, also TLR2/TLR1-specific ligands will be recognized to some extent. As a positive control, we used the synthetic diacylated LP FSL-1. In addition, we treated the pnLTA of strain D39Δcps with H2O2, thus oxidizing the thioether bond of the terminal lipid attached to the cysteine residue unit in the LPs known to be essential for TLR2-dependent signaling. Because this derivatization results in the destruction of the sulfur region (25) essential for the recognition by TLR2, this test is a reliable control for TLR2-dependent LP contamination (21, 33). Our experiments showed that only the pnLTA of strain D39Δcps possesses TLR2-stimulating activity. H2O2 treatment as well as isolating LTA from Δlgt mutant strains resulted in TLR2-inactive LTA preparations. In addition, all LTA preparations have been tested to be devoid of TLR4-stimulating (LPS) contaminants (data not shown).

FIGURE 9.

Cytokine release induced by different LTA preparations. A, induction of IL-8 in HEK293 cells transiently transfected with TLR2/TLR6/CD14. Cells were stimulated with the indicated amounts of LTA preparations or synthetic lipoprotein FSL-1 for 18 h. The content of IL-8 in the supernatants was analyzed by ELISA. Data are shown as means ± S.D. (error bars) and represent one of three independent experiments; assays were performed in triplicates. B, induction of IL-6 in hMNCs. Cells were stimulated with the indicated amounts of LTA preparations or LPS for 20 h. The content of IL-6 in the supernatants was analyzed by ELISA. Data are shown as means ± S.D. and represent one of three independent experiments; assays were performed in triplicates.

The use of Δlgt mutants allowed us to investigate the “real” immunostimulatory potency of a LTA preparation without the additive or even synergistic impact of the proinflammatory LPs (21). Therefore, we stimulated hMNCs and measured the IL-6 production. As depicted in Fig. 9B, the TLR2-active LTA preparation of S. pneumoniae D39Δcps led to the strongest induction of IL-6. Interestingly, the LTA preparation isolated from S. pneumoniae strain D39ΔcpsΔlgt was still capable of inducing IL-6 production, whereas the preparation from S. aureus SA113Δlgt was not. The immunostimulatory activity of pnLTA was expected, because in an earlier work, synthetic LTA of the S. pneumoniae type (with only one RU and devoid of contaminating TLR2 activity) showed cytokine induction in hMNCs as well (45). However, we could not reproduce the proinflammatory activity of LTA from S. aureus published previously (19, 22, 46). This difference in biological activity led us to the conclusion that structural differences in LTAs of S. pneumoniae and S. aureus (structure of used LTA from S. aureus SA113Δlgt is depicted in supplemental Fig. S4) have an important impact on how or if these bacterial LTAs are sensed by the host immune system.

DISCUSSION

The present study provides a structural reevaluation of the LTA of S. pneumoniae, which became necessary due to controversial structural reports present in the literature. When combining NMR- and MS-based data, we were able to revise the pnLTA structure and could make structural corrections on the actual pnLTA model (Fig. 1) in four significant details. Our revised model (Fig. 10) now appears to be consistent with all known structural, genetic, and biosynthetic data available so far.

FIGURE 10.

Revised structural model for pneumococcal LTA. RU contain the same pseudopentasaccharide (AATGalp–Glcp–Rib-ol-5-P–6-O-P-Cho-GalpNAc–6-O-P-Cho-GalpNAc) as proposed before, but the terminal RU can occur with or without 6-O-P-Cho substitution. In contrast to the former model (Fig. 1) only the first repeating unit is β-1-linked to the lipid anchor (glucose-diacylglycerol), and all other RUs are α-1-linked to the previous one. Hydroxyl groups of Rib-ol-5-P are only substituted by d-Ala potentially. The chain length of pnLTA seems to be 4–8 RU in general.

The first repeating unit (RU 1) attached to the lipid anchor is structurally identical to the other following RUs (RU 2 to n). However, this first pseudopentasaccharide, (→4)-6-O-P-Cho-α-d-GalpNAc-(1→3)-6-O-P-Cho-β-d-GalpNAc-(1→1)-Rib-ol-5-P-(O→6)-β-d-Glcp-(1→3)-AATGalp(1→), represents the only one that is β-linked to the sugar to which it is attached, in this case the lipid anchor ((→3)-α-d-Glcp-(1→3)-acyl2Gro). By contrast, all other RUs, representing an elongation of the carbohydrate part in the pnLTA molecule, are α-1-linked to the precedent RU. This detail appears to be minor; however, it is essential for the investigation of the enzymes involved in the biosynthesis and in the transfer of the TA precursor to either the lipid anchor to form the LTA or to the PGN to form the WTA. Based on experimental data and bioinformatic analysis of the S. pneumoniae R6 genome, it has been predicted (20) that the synthesis of the repeating unit starts with the conversion of UDP-GlcNAc into UDP-AATGal (controlled by Spr0092 and Spr1654; all protein names and numbers are from S. pneumoniae R6). The AATGal is then transferred by Spr1655 to an undecaprenyl-diphosphate linker; the configuration of this linkage is not known. Sequentially, glucose, ribitolphosphate, and the two GalNAc residues are added by Spr0091, LicD3 (Spr1125), Spr1123, and Spr1124, respectively. Finally, P-Cho residues are incorporated on both O-6-positions of the GalNAc residues by LicD1 (Spr1151) and LicD2 (Spr1152) to form the complete repeating unit building block. The question where and how the polymerization of the RU takes place is not clearly answered yet. It is proposed that the membrane protein Spr1222 catalyzes this reaction on the cytosolic side of the membrane, but the experimental proof is still lacking. However, our structural analysis clearly shows that the responsible polymerase specifically catalyzes α-linkages between the RUs. The TA precursor chains are then translocated to the outer side of the membrane, probably by TacF (Spr1150), and are then transferred to the lipid anchor to form the LTA or to the PGN to form the WTA. Especially LytR (Spr1759) and Psr (Spr1226), both representing phosphotransferases, are suggested to be involved in these processes. It is still unknown which enzyme is responsible for the formation of which cell wall polymer and if they transfer the RU chain under retention or conversion of the configuration of the first AATGal. Moreover, the configuration of the AATGal being presumably attached via a phosphate to the PGN in pneumococcal WTA is not known. Chemical (6) as well as enzymatic (48) approaches failed so far to clarify this question. Therefore, additional work combining genetic approaches and structural analysis has to be performed to further decipher the steps of pneumococcal TA biosynthesis.

Using mild hydrazine treatment, by which all ester-bound residues are removed, we here were able to analyze the structure of pnLTA with high resolution NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry in an unprecedented detailed manner, thus revealing structural details of pnLTA, which so far escaped a detailed NMR-based structural analysis. As a result, we could clarify the inconsistencies of the current structural model (Fig. 1). With respect to the determination of the number of RUs, our MS results and the integration of signals obtained from the 1H NMR from hydrazine-treated pnLTA are in good agreement with published MS data (13). In both analyses, pnLTA with six or seven RUs are the predominantly occurring variants.

Contrary to previous data (5, 13, 14, 17), we observed for the first time that the terminal RU can occur in different variants. In the pnLTA isolated from strain D39Δcps(Δlgt), both GalpNAc-residues of the Forssman antigen terminus were substituted with P-Cho in O-6-positions independently of the pH value used in the culture medium. In contrast, the pnLTA isolated from strain TIGR4Δcps possessed a terminus in which one or both P-Cho-residues in the Forssman disaccharide were missing but only if bacteria had been grown under mild acidic conditions. This indicates a stepwise removal of the two terminal P-Cho-residues. However, the enzyme(s) involved in this modification and the reason for the strain and pH dependence have to be investigated in more detail. Interestingly, the substitution of the Forssman antigen terminus with P-Cho has no bearing on the detection by a monoclonal anti-Forssman GSL antibody (IgM). This suggests that the used anti-Forssman GSL antibody recognizes the Forssman disaccharide mostly by protons and carbons in the pyranosidic GalNAc residues of the α-d-GalpNAc-(1→3)-β-d-GalpNAc-(1→) disaccharide. This indicates that the C-6 moieties of the disaccharide are not part of the binding epitope of the IgM mAb.

In addition, the improved NMR analysis of O-deacyl pnLTA allowed us to reassign the signal at δH 5.08 ppm (d, 3J1,2 3.9 Hz) which was originally thought to result from an α-d-GalpNAc substituent at the Rib-ol-5-P. In this study we could clearly demonstrate that this signal originates from the anomeric proton of the terminal 6-O-P-Cho-α-d-GalpNAc. Besides, we have no evidence for a glycosyl substitution of the Rib-ol-5-P in our pnLTA preparations. This absence is consistent with the recent genomic study of the biosynthetic pathway of pneumococcal teichoic acids (20). This study did not identify possible genes encoding enzymes responsible for an α-GalpNAc modification of Rib-ol-5-P.

Furthermore, we demonstrated that the loss of function of Lgt in S. pneumoniae strain D39Δcps does not alter the structure of its pnLTA. Using HEK293 cells transiently transfected with TLR2/TLR6/CD14, we further proved in a biological system the efficiency of this mutagenesis. The LTA preparation received from the cultivation of the Δlgt mutant induced no release of IL-8, in contrast to the pnLTA preparation of the isogenic parental strain. This allowed us to investigate the immunostimulatory properties of pnLTA in hMNCs independently of those caused by TLR2 activation induced by contaminating LPs. In contrast to LTA obtained from S. aureus SA113Δlgt, the pnLTA of strain D39ΔcpsΔlgt was able to induce IL-8 secretion although this activity is weak in comparison with LPS. The receptor(s) and the mechanism through which LTA stimulates the innate immune system are only rarely investigated. A reasonable explanation for a putative LTA receptor could be the C-type lectin pathway of complement, although these experiments have not been performed using LTA preparations isolated from Δlgt mutants (47, 49–51). However, in contrast to former reports using staphylococcal LTA (19, 22, 46), our LTA preparation obtained from S. aureus strain SA113Δlgt showed no immunostimulation at all, not even in hMNCs. Hence, especially the structural requirements that are essential for this proposed complement activation must be investigated in more detail.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge S. Thomsen, B. Buske, H. Kässner, S. Al-Badri, and B. Kunz for excellent technical assistance as well as Prof. Dr. O. Holst for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (ZA 149/6–1 and HA 3125/2-1) and the cluster of excellence “Inflammation at Interfaces.”

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1–S4.

- PGN

- peptidoglycan

- AATGal

- 2-acetamido-4-amino-2,4,6-trideoxygalactose

- ABTS

- diammonium-2,2′-azino-di-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)

- DAG

- diacylglycerol

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- FT

- Fourier transform

- ICR

- ion cyclotron resonance

- Gro

- glycerol

- GSL

- glycosphingolipid

- hMNC

- human mononuclear cell

- HMQC

- heteronuclear multiple quantum correlation

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum correlation

- LTA

- lipoteichoic acid

- pnLTA

- pneumococcal LTA

- P-Cho

- phosphorylcholine

- pnLTAN2H4

- hydrazine-treated pneumococcal LTA (O-deacyl pnLTA)

- pNP-Fa

- para-nitrophenyl-Forssman antigen

- Rib-ol-5-P

- ribitol-5-phosphate

- RU

- repeating unit(s)

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- TOCSY

- total correlation spectroscopy

- WTA

- wall teichoic acid

- TA

- teichoic acid

- LP

- lipoprotein

- Galp

- galactopyranose

- Glcp

- glucopyranose.

REFERENCES

- 1. Weidenmaier C., Peschel A. (2008) Teichoic acids and related cell-wall glycopolymers in Gram-positive physiology and host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 276–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. López R. (2004) Streptococcus pneumoniae and its bacteriophages. One long argument. Int. Microbiol. 7, 163–171 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kadioglu A., Weiser J. N., Paton J. C., Andrew P. W. (2008) The role of Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence factors in host respiratory colonization and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 288–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schmidt R. R., Pedersen C. M., Qiao Y., Zähringer U. (2011) Chemical synthesis of bacterial lipoteichoic acids. An insight on its biological significance. Org. Biomol. Chem. 9, 2040–2052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fischer W., Behr T., Hartmann R., Peter-Katalinić J., Egge H. (1993) Teichoic acid and lipoteichoic acid of Streptococcus pneumoniae possess identical chain structures. Eur. J. Biochem. 215, 851–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fischer W. (1997) Pneumococcal lipoteichoic and teichoic acid. Microb. Drug Resist. 3, 309–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bergmann S., Hammerschmidt S. (2006) Versatility of pneumococcal surface proteins. Microbiology 152, 295–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gamez G., Hammerschmidt S. (2012) Combat pneumococcal infections. Adhesins as candidates for protein-based vaccine developement. Curr. Drug Targets 13, 323–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Voss S., Gámez G., Hammerschmidt S. (2012) Impact of pneumococcal microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules on colonization. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 27, 246–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cundell D. R., Gerard N. P., Gerard C., Idanpaan-Heikkila I., Tuomanen E. I. (1995) Streptococcus pneumoniae anchor to activate human cells by the receptor for platelet-activating factor. Nature 377, 435–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Radin J. N., Orihuela C. J., Murti G., Guglielmo C., Murray P. J., Tuomanen E. I. (2005) β-Arrestin 1 participates in platelet-activating factor receptor-mediated endocytosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 73, 7827–7835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Behr T., Fischer W., Peter-Katalinić J., Egge H. (1992) The structure of pneumococcal lipoteichoic acid. Eur. J. Biochem. 207, 1063–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seo H. S., Cartee R. T., Pritchard D. G., Nahm M. H. (2008) A new model of pneumococcal lipoteichoic acid structure resolves biochemical, biosynthetic, and serologic inconsistencies of the current model. J. Bacteriol. 190, 2379–2387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fischer W. (2000) Pneumococcal lipoteichoic and teichoic acids. in Streptococcus pneumoniae: Molecular Biology and Mechanisms of Disease, pp. 155–177, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kinjo Y., Illarionov P., Vela J. L., Pei B., Girardi E., Li X., Li Y., Imamura M., Kaneko Y., Okawara A., Miyazaki Y., Gómez-Velasco A., Rogers P., Dahesh S., Uchiyama S., Khurana A., Kawahara K., Yesilkaya H., Andrew P. W., Wong C.-H., Kawakami K., Nizet V., Besra G. S., Tsuji M., Zajonc D. M., Kronenberg M. (2011) Invariant natural killer T cells recognize glycolipids from pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria. Nat. Immunol. 12, 966–974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heissigerova H., Breton C., Moravcova J., Imberty A. (2003) Molecular modeling of glycosyltransferases involved in the biosynthesis of blood group A, blood group B, Forssman, and iGb3 antigens and their interaction with substrates. Glycobiology 13, 377–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Draing C., Pfitzenmaier M., Zummo S., Mancuso G., Geyer A., Hartung T., von Aulock S. (2006) Comparision of lipoteichoic acid from different serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 33849–33859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Courtney H. S., Simpson W. A., Beachey E. H. (1986) Relationship of critical micelle concentrations of bacterial lipoteichoic acids to biological activities. Infect. Immun. 51, 414–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morath S., Geyer A., Hartung T. (2001) Structure-function relationship of cytokine induction by lipoteichoic acid from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Exp. Med. 193, 393–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Denapaite D., Brückner R., Hakenbeck R., Vollmer W. (2012) Biosynthesis of teichoic acids in Streptococcus pneumoniae and closely related species. Lessons from genomes. Microb. Drug Resist. 18, 344–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zähringer U., Lindner B., Inamura S., Heine H., Alexander C. (2008) TLR2. Promiscuous or specific? A critical re-evaluation of a receptor expressing apparent broad specificity. Immunobiology 213, 205–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Henneke P., Morath S., Uematsu S., Weichert S., Pfitzenmaier M., Takeuchi O., Müller A., Poyart C., Akira S., Berner R., Teti G., Geyer A., Hartung T., Trieu-Cuot P., Kasper D. L., Golenbock D. T. (2005) Role of lipoteichoic acid in the phagocyte response to group B Streptococcus. J. Immunol. 174, 6449–6455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stoll H., Dengjel J., Nerz C., Götz F. (2005) Staphylococcus aureus deficient in lipidation of prelipoproteins is attenuated in growth and immune activation. Infect. Immun. 73, 2411–2423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hashimoto M., Tawaratsumida K., Kariya H., Kiyohara A., Suda Y., Krikae F., Kirikae T., Götz F. (2006) Not lipoteichoic acid but lipoproteins appear to be the dominant immunobiologically active compounds in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Immunol. 177, 3162–3169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jin M. S., Kim S. E., Heo J. Y., Lee M. E., Paik S.-G., Lee H., Lee J.-O. (2007) Crystal structure of the TLR1-TLR2 heterodimer induced by binding of a tri-acylated lipopeptide. Cell 130, 1071–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kang J. Y., Nan X., Jin M. S., Youn S.-J., Ryu Y. H., Mah S., Han S. H., Lee H., Paik S.-G., Lee J.-O. (2009) Recognition of lipopeptide patterns by toll-like receptor 2-toll-like receptor 6 heterodimer. Immunity 31, 873–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Farhat K., Riekenberg S., Heine H., Debarry J., Lang R., Mages J., Buwitt-Beckmann U., Röschmann K., Jung G., Wiesmüller K.-H., Ulmer A. J. (2008) Heterodimerization of TLR2 with TLR1 or TLR6 expands the ligand spectrum but does not lead to differential signaling. J. Leukoc. Biol. 83, 692–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rennemeier C., Hammerschmidt S., Niemann S., Inamura S., Zähringer U., Kehrel B. E. (2007) Thrombospondin-1 promotes cellular adherence of Gram-positive pathogens via recognition of peptidoglycan. FASEB J. 21, 3118–3132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Petit C. M., Brown J. R., Ingraham K., Bryant A. P., Holmes D. J. (2001) Lipid modification of prelipoproteins is dispensable for growth in vitro but essential for virulence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 200, 229–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hávarstein L. S., Coomaraswamy G., Morrison D. A. (1995) An unmodified heptadecapeptide pheromone induces competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 11140–11144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fischer W., Koch H. U., Haas R. (1983) Improved preparation of lipoteichoic acids. Eur. J. Biochem. 133, 523–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lowry O. H., Roberts N. R., Leiner K. Y., Wu M. L., Farr A. L. (1954) The quantitative histochemistry of brain. I. Chemical methods. J. Biol. Chem. 207, 1–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Morr M., Takeuchi O., Akira S., Simon M. M., Mühlradt P. F. (2002) Differential recognition of structural details of bacterial lipopeptides by toll-like receptors. Eur. J. Immunol. 32, 3337–3347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Elling L., Zervosen A., Gutiérrez Gallego R., Nieder V., Malissard M., Berger E. G., Vliegenthart J. F., Kamerling J. P. (1999) UDP-N-acetyl-α-d-glucosamine as acceptor substrate of β-1,4-galactosyltransferase. Enzymatic synthesis of UDP-N-acetyllactosamine. Glycoconjugate J. 16, 327–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Böyum A. (1968) Isolation of mononuclear cells and granulocytes from human blood. Isolation of monuclear cells by one centrifugation, and of granulocytes by combining centrifugation and sedimentation at 1 g. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. Suppl. 97, 77–89 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Debarry J., Garn H., Hanuszkiewicz A., Dickgreber N., Blümer N., von Mutius E., Bufe A., Gatermann S., Renz H., Holst O. (2007) Acinetobacter lwoffii and Lactococcus lactis strains isolated from farm cowsheds possess strong allergy-protective properties. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 119, 1514–1521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Saito T., Hakomori S. I. (1971) Quantitative isolation of total glycosphingolipids from animal cells. J. Lipid Res. 12, 257–259 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kundu S. K., Roy S. K. (1978) A rapid and quantitative method for the isolation of gangliosides and neutral glycosphingolipids by DEAE-silica gel chromatography. J. Lipid Res. 19, 390–395 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ueno K., Ando S., Yu R. K. (1978) Gangliosides of human, cat, and rabbit spinal cords and cord myelin. J. Lipid Res. 19, 863–871 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ledeen R. W., Yu R. K. (1982) Gangliosides. Structure, isolation, and analysis. Methods Enzymol. 83, 139–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bethke U., Kniep B., Mühlradt P. F. (1987) Forssman glycolipid, an antigenic marker for a major subpopulation of macrophages from murine spleen and peripheral lymph nodes. J. Immunol. 138, 4329–4335 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bethke U., Müthing J., Schauder B., Conradt P., Mühlradt P. F. (1986) An improved semi-quantitative enzyme immunostaining procedure for glycosphingolipid antigens on high performance thin layer chromatograms. J. Immunol. Methods 89, 111–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Müthing J., Meisen I., Zhang W., Bielaszewska M., Mormann M., Bauerfeind R., Schmidt M. A., Friedrich A. W., Karch H. (2012) Promiscuous Shiga toxin 2e and its intimate relationship to Forssman. Glycobiology 22, 849–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Houliston R. S., Bernatchez S., Karwaski M.-F., Mandrell R. E., Jarrell H. C., Wakarchuk W. W., Gilbert M. (2009) Complete chemoenzymatic synthesis of the Forssman antigen using novel glycosyltransferases identified in Campylobacter jejuni and Pasteurella multocida. Glycobiology 19, 153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pedersen C. M., Figueroa-Perez I., Lindner B., Ulmer A. J., Zähringer U., Schmidt R. R. (2010) Total synthesis of lipoteichoic acid of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 49, 2585–2590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Morath S., Stadelmaier A., Geyer A., Schmidt R. R., Hartung T. (2002) Synthetic lipoteichoic acid from Staphylococcus aureus is a potent stimulus of cytokine release. J. Exp. Med. 195, 1635–1640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dehus O., Pfitzenmaier M., Stuebs G., Fischer N., Schwaeble W., Morath S., Hartung T., Geyer A., Hermann C. (2011) Growth temperature-dependent expression of structural variants of Listeria monocytogenes lipoteichoic acid. Immunobiology 216, 24–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bui N. K., Eberhardt A., Vollmer D., Kern T., Bougault C., Tomasz A., Simorre J.-P., Vollmer W. (2012) Isolation and analysis of cell wall components from Streptococcus pneumoniae. Anal. Biochem. 421, 657–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hummell D. S., Swift A. J., Tomasz A., Winkelstein J. A. (1985) Activation of the alternative complement pathway by pneumococcal lipoteichoic acid. Infect. Immun. 47, 384–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Loos M., Clas F., Fischer W. (1986) Interaction of purified lipoteichoic acid with the classical complement pathway. Infect. Immun. 53, 595–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lynch N. J., Roscher S., Hartung T., Morath S., Matsushita M., Maennel D. N., Kuraya M., Fujita T., Schwaeble W. J. (2004) l-Ficolin specifically binds to lipoteichoic acid, a cell wall constituent of Gram-positive bacteria, and activates the lectin pathway of complement. J. Immunol. 172, 1198–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.