Background: The evolution of the plant xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolase (XTH) genes in glycoside hydrolase family 16 (GH16) is enigmatic.

Results: A unique, mixed function endo(xylo)glucanase from black cottonwood has been biochemically and structurally characterized.

Conclusion: This enzyme is an important link between extant bacterial endoglucanases and plant XTH gene products.

Significance: New insights into the molecular evolution of XTH gene products and further unification of GH16 enzymes have been gained.

Keywords: Carbohydrate Processing, Cellulase, Enzyme Kinetics, Enzyme Structure, Glycoside Hydrolases, Plant Cell Wall, Polysaccharide, Licheninase, Xyloglucan, Xyloglucan Endotransglycosylase/Hydrolase (XTH)

Abstract

The large xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolase (XTH) gene family continues to be the focus of much attention in studies of plant cell wall morphogenesis due to the unique catalytic functions of the enzymes it encodes. The XTH gene products compose a subfamily of glycoside hydrolase family 16 (GH16), which also comprises a broad range of microbial endoglucanases and endogalactanases, as well as yeast cell wall chitin/β-glucan transglycosylases. Previous whole-family phylogenetic analyses have suggested that the closest relatives to the XTH gene products are the bacterial licheninases (EC 3.2.1.73), which specifically hydrolyze linear mixed linkage β(1→3)/β(1→4)-glucans. In addition to their specificity for the highly branched xyloglucan polysaccharide, XTH gene products are distinguished from the licheninases and other GH16 enzyme subfamilies by significant active site loop alterations and a large C-terminal extension. Given these differences, the molecular evolution of the XTH gene products in GH16 has remained enigmatic. Here, we present the biochemical and structural analysis of a unique, mixed function endoglucanase from black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa), which reveals a small, newly recognized subfamily of GH16 members intermediate between the bacterial licheninases and plant XTH gene products. We postulate that this clade comprises an important link in the evolution of the large plant XTH gene families from a putative microbial ancestor. As such, this analysis provides new insights into the diversification of GH16 and further unites the apparently disparate members of this important family of proteins.

Introduction

Plant cell walls are complex biocomposites, comprising semicrystalline and amorphous polysaccharides, polyphenolics, structural proteins, and inorganics, which are of biological, ecological, and industrial importance (1–3). In addition to forming the basis of the agricultural and forest products industries, plant cell walls represent a vast sink in the global carbon cycle. Thus, understanding molecular mechanisms of plant cell wall biosynthesis and morphogenesis is fundamentally important (4).

Depending on the cell type and developmental stage, carbohydrates typically compose at least three-fourths of the plant cell wall dry weight (1, 5). Semicrystalline cellulose is the main load-bearing polymer embedded in a hydrated network of matrix glycans. A diversity of primary plant cell wall polysaccharide compositions can be observed (6). For example, the walls of dicots and non-commeneloid monocots contain xyloglucans as the primary matrix polysaccharide, whereas the grasses utilize mixed linkage β(1→3)/β(1→4)-glucans in this role (1, 5). Due to this predominance of structural carbohydrates, the biosynthesis and enzyme-catalyzed rearrangement of polysaccharides underpin contemporary cell wall models (4). Indeed, plant genomes encode large repertoires of glycosyltransferases, glycoside hydrolases, and transglycosidases, often in large, multigene families (7–10).

In the context of postbiosynthetic plant cell wall remodeling, there is a sustained interest in the xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolase (XTH)2 gene family. This is due to the remarkable ability of some gene products to catalyze matrix polysaccharide rearrangement with essentially no chain hydrolysis (XET activity, EC 2.4.1.207). On the other hand, a limited number of XTH genes encode predominant hydrolases (XEH, EC 3.2.1.151) that operate in germinating seeds, ripening fruit, or expanding tissues (11, 12). Notably, contemporary enzyme structure-function analyses have led to a refined phylogenetic delineation of the disparate transglycosylating and hydrolytic activities individual XTH gene products, which number in the range of ∼20–60 in diverse plants (11, 13).

However, the molecular evolution of the XTH gene products in the larger context of glycoside hydrolase family 16 (GH16) (14) remains enigmatic. In addition to the plant XTH gene products, GH16 counts a broad range of microbial endoglucanases and endogalactanases among its functionally characterized members, spanning those active on terrestrial and marine polysaccharides to yeast cell wall chitin/β-glucan transglycosylases (13). Despite significant sequence divergence, all GH16 enzymes are predicted to share both a common overall β-jellyroll protein fold and the canonical retaining GH catalytic mechanism (15–17).

Previous whole-family phylogenetic analyses have suggested that the closest relatives to the XTH gene products are the bacterial licheninases (EC 3.2.1.73), which specifically hydrolyze β(1→4) linkages in mixed linkage β(1→3)/β(1→4)-glucans (15). XTH gene products are, however, distinguished from the licheninases and all other GH16 enzyme classes by significant differences in their common β-jellyroll protein structure. These differences include major loop alterations and a unique C-terminal extension, in addition to a singular specificity for a highly branched polysaccharide substrate (13). Exactly how the XTH gene products may have arisen from licheninases has heretofore remained unclear.

Here, we present the biochemical and structural analysis of an unusual, mixed function endoglucanase from black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa). This research reveals a small clade of GH16 members intermediate between the bacterial licheninases and plant XTH gene products. We postulate that this clade comprises an important link in the evolution of the large plant XTH gene families from a putative microbial ancestor. As such, this analysis provides new insights into the diversification of GH16 and further unites the apparently disparate members of this important family of proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Substrates

Xyloglucan, barley mixed linkage glucan (medium viscosity), Icelandic moss lichenan, laminarin, lupin β-galactan, wheat arabinoxylan, carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), cellooligosaccharides, and mixed linkage glucooligosaccharides were from Megazyme. Hydroxyethyl cellulose was from Fluka. Xyloglucooligosaccharides were prepared as described previously (18).

Bioinformatic and Phylogenetic Analyses

The EG16-like enzymes were found using PtEG16 as the query with BLASTp at the Phytozome Web site (October 2012). The Charophyta sequence CHARA2 was manually transcribed from Ref. 19, and an expressed sequence tag from Coleochaete nitellarum was obtained from GenBankTM (accession number HO204633). Possible localization and post-translational modifications were analyzed by SignalP (20), ChloroP (21), LipoP (22), and GPP (23). These sequences were also included in the phylogeny: XTH gene products from rice, Oryza sativa (OsXTHs), and Arabidopsis (AtXTHs); Group III-A sequences from Ref. 11; and selected Group IIIA sequences from TIGR (24). Two Bacillus licheninases (PDB codes 1gbg and 1u0a) were included to root the tree. Sequences were aligned using MUSCLE (25), and the alignment was edited manually in Bioedit (26), guided by the available three-dimensional structures. Maximum likelihood and Bayesian phylogenies were built using PhyML 3.0 (27) and MrBayes 3.1.2 (28), respectively. In PhyML, the reliability of nodes was tested by 100 resamplings. In MrBayes, 2 × 106 generations were run with a sample frequency of 100. Blosum62 was used as the amino acid substitution matrix in both PhyML and MrBayes. Trees were drawn with MEGA5 (29).

Protein Expression and Purification

PtEG16 cDNA (originally codon-optimized for Pichia pastoris expression; GENEART AG) was cloned into Expresso N-His vector with an N-terminal His6 tag (Lucigen). PtEG16 was produced in Hl control Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells (Lucigen) grown in Terrific Broth at 37 °C at 200 rpm to an A600 of 0.8 and then induced by the addition of isopropyl β-d-galactopyranose to a final concentration of 0.5 mm. During the induction phase, the culture was kept at 25 °C overnight. Cells were then collected by centrifugation at 4800 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The cells were resuspended in buffer A (25 mm sodium phosphate, 0.5 m NaCl, and 25 mm imidazole, pH 7.5) and ultrasonicated to liberate cytoplasmic proteins. The supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 24,700 × g for 15 min at 4 °C and passed through a 5-ml HisTrap FF Crude column (GE Healthcare). The protein was eluted using a 10-column volume-long linear gradient with buffer B (25 mm sodium phosphate, 0.5 m NaCl, and 0.5 m imidazole, pH 7.5). Fractions containing PtEG16 were pooled, and DTT was added to a final concentration of 2 mm. After incubation at room temperature for 2 h, the sample was purified further using an XK 16/100 Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare), pre-equilibrated with 20 mm MOPS, 1 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, pH 7.5. Monomeric PtEG16 fractions were pooled, concentrated using Vivaspin20 5 kDa (PES) centrifugal concentrators, and stored at 4 °C.

PtEG16 enriched in 15N for NMR experiments was produced using E. coli cells grown at 37 °C at 200 rpm to an A600 of 1 in LB, centrifuged at 3000 × g for 10 min, and then gently resuspended in M9 medium containing 1 g/liter 15NH4Cl and 0.5 mm isopropyl β-d-galactopyranose. The induced culture was kept at 16 °C for 30 h before the cells were collected by centrifugation at 4800 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The 15N-labeled PtEG16 was treated and purified as described above for the non-labeled enzyme.

Triple-labeled PtEG16-1 (2D, 13C, and 15N) was produced by first inoculating 600 ml of M9 medium with 3 ml of overnight LB culture (H2O) and kept at 37 °C at 200 rpm until an A600 of 0.5. The cells were gently pelleted by centrifugation at 1000 × g for 8 min and resuspended in 600 ml of M9 medium containing 1 g/liter 15NH4Cl, 2.5 g/liter 2H7/13C6-glucose in D2O. At A600 0.65, the culture was moved to 25 °C and induced after 20 min with isopropyl β-d-galactopyranose at a final concentration of 1 mm. After overnight induction, the cells were harvested at 4800 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. Cells were sonicated and initially purified on a 5-ml HisTrap FF crude column as for the unlabeled protein. After initial purification, the buffer was exchanged to 25 mm MOPS, 2 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, pH 7.5. To reintroduce 1H on the nitrogens, the triple-labeled PtEG16 was denatured by 1:20 dilution in 8 m urea, 25 mm Tris, pH 7.5, with 2 mm DTT prepared in H2O. On-column refolding was performed essentially as described (30), with the exception that 2 mm DTT was added to all buffers. The refolded triple-labeled PtEG16 was buffer-exchanged to 20 mm MOPS, 2 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, pH 7.5, before NMR experiments.

Activity on Polysaccharides Detected by Gel Permeation Chromatography

Assays in a total volume of 150 μl, containing 2.5 g/liter polysaccharide, 30 mm NH4OAc, 0.25 mm DTT, and 24 μg/ml PtEG16, were incubated for 0, 6, 20, 60, 180, and 480 min and overnight at 22 °C. The reactions were stopped by heating to 95 °C for 10 min. The samples were then lyophilized and dissolved in 200 μl of DMSO before analysis by gel permeation chromatography, as described previously (18). Control assays without enzyme were also monitored to detect background hydrolysis. Carboxymethyl cellulose and Konjac glucomannan (Megazyme) were insoluble in DMSO and were therefore analyzed by high performance anion exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD).

HPAEC-PAD

Samples were analyzed on a Dionex ICS-5000 HPAEC-PAD system using a Dionex CarboPac PA-200 column. Four different programs (supplemental Table S1) were used, depending on the sample. Program A was used to identify the limit digestion products of lichenan and mixed linkage glucans versus standard samples of cello-oligosaccharides (degree of polymerization 1–6) and three mixed linkage glucan tetraoses: MLGA, G3G4G4G; MLGB, G4G4G3G; and MLGC, G4G3G4G. Program B (18) was used to analyze the limit digestion products of all other polysaccharides. Potential transglycosylation products at maximal substrate concentrations (10-min reactions) were analyzed by Program C (for cello-oliogsaccharides and mixed linkage glucan oligosaccharides) and Program D (for XXXGXXXG).

Quantitative Kinetic Analysis of PtEG16 Activity on Oligosaccharides

Kinetic quantitation under initial rate conditions was determined on cello-oligosaccharides (degree of polymerization 2–6) and the xylogluco-oligosaccharide XXXGXXXG using HPAEC-PAD. The pH optimum of the enzyme was determined by incubation of 30 nm PtEG16 with 400 μm cellohexaose and 50 mm buffer (sodium citrate for pH 3–6.5 and MOPS for pH 6.5–8.1) in a final volume of 40 μl. All subsequent assays with oligosaccharide substrates were performed in 40-μl reactions buffered with 25 mm sodium citrate, pH 5.25. In all cases, assays were maintained at 22 °C and terminated by the addition of 10 μl of 1 m NaOH prior to analysis using Program A (supplemental Table S1). Peak areas were quantified by integration and converted to molar amounts based on standard curves in the range 1–50 μm.

Matrix-assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) Analysis

Oligosaccharide products were analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in positive ion mode on an LT3 Plus mass spectrometer (SAI Ltd.) operated by the MALDI Mainframe 2, MALDI Control software (version 1.03.51, SAI Ltd.). Samples were supplemented with NaCl to a final concentration of 20 mm, and 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (10 g/liter in water) was used as the matrix.

NMR Spectroscopy

Resonance assignments for the main chain 1HN, 15N, and 13C nuclei in the 220-residue carbon-perdeuterated 13C/15N-labeled His6-tagged PtEG16 were obtained using standard pulse sequences recorded at 25 °C on a Bruker Avance III 600-MHz spectrometer equipped with a TCI CryoProbe. The resulting 15N TROSY HSQC (31–35), HNCACB (36, 37), HN(CO)CACB (36, 37), HNCO (38), and HN(CA)CO (37) spectra were processed with NMRPipe (39) and analyzed with Sparky (40). The 1H and 15N dimensions were corrected by +46 Hz and −46 Hz, respectively, to adjust for the TROSY shift. Chemical shift-based secondary structural predictions were obtained using the programs MICS (41), TALOS+ (42), and δ2D (43). Referencing and adjustment of the carbon shifts for deuterium isotope effects were done using TALOS+ (42).

RESULTS

Bioinformatics Analysis Reveals a Unique XTH-like Gene Product of the P. trichocarpa Genome

Using amino acid sequence alignments, we identified a unique protein encoded by the P. trichocarpa genome (genome version 2.2, locus POPTR_0002s15460, also known as eugene3.00021425 or PtXTH8 (8)). This protein clearly lacked the C-terminal extension diagnostic of GH16 XTH gene products (44, 45) (Pfam XET_C (PF06955) (46)) but otherwise showed significant sequence similarity to known XETs and XEHs (Fig. 1). A BLASTp search of this sequence against predicted proteomes available at Phytozome revealed that the genomes of many embryophytes encode one or more homologous proteins with Expect (E) values less than 10−80. In comparison, proteins possessing the XTH-specific C-terminal extension typically had E values above 10−35 in this analysis (data not shown), which further strengthened the conclusion that the POPTR_0002s15460 gene product (hereafter renamed as “P. trichocarpa endoglucanase 16” (PtEG16) in accordance with biochemical data; see below) and its homologs indeed composed a separate clade. A multiple-protein sequence alignment of these homologs from diverse plants is shown in supplemental Fig. S1. Notably, none has predicted signal peptides for apoplast, organelle, or membrane localization, according to SignalP (20), ChloroP (21), and LipoP (22).

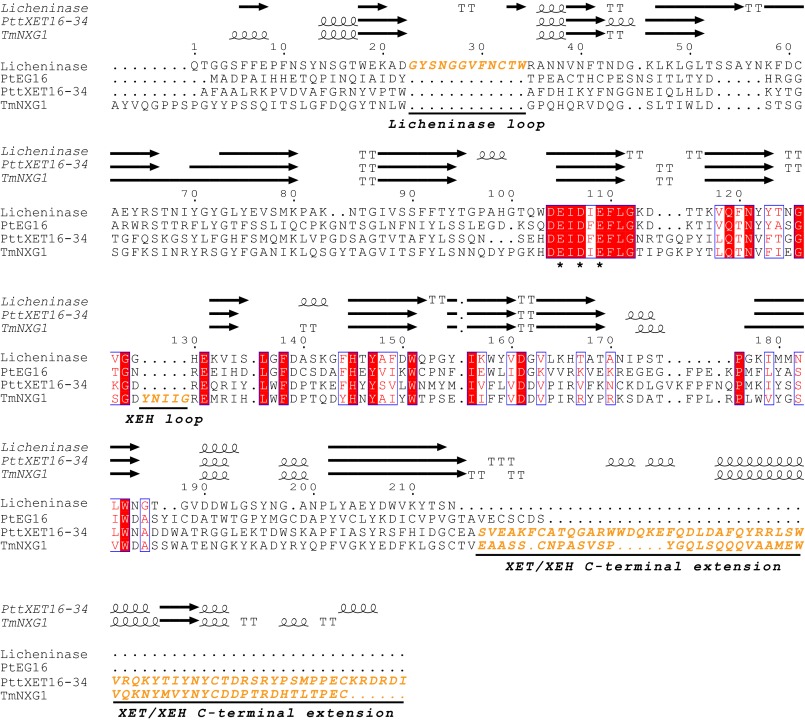

FIGURE 1.

Amino acid sequence alignment of Paenibacillus macerans licheninase (PDB code 1u0a), P. trichocarpa endoglucanase 16 (PtEG16, POPTR_0002s15460), P. tremula x tremuloides xyloglucan endotransglycosylase 16-34 (PttXET16-34, PDB code 1umz), and Tropaeolum majus xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (TmNXG1, PDB code 2uwa) of GH16. The alignment was performed with MUSCLE (25), and secondary structure elements (strands (arrows), helices (spirals), and turns (T)) from the corresponding crystal structures were added with ESPript (83) (protein names are in italic type). Conserved catalytic residues are marked with asterisks.

We then performed independent Bayesian and maximum likelihood phylogenetic analyses with these sequences and all 33 Arabidopsis thaliana and 29 Oryzae sativa XTH gene products (9) as representative dicot and monocot sequences, respectively. Crystallographically characterized XETs and XEHs (11, 45) as well as select phylogenetic Group III-A XTH gene products were also included in this analysis. The sequences of two Bacillus GH16 licheninases with known tertiary structures (47, 48) were used as more distant outliers to root the phylogenetic trees. In this analysis, only the common GH16 domain was used (i.e. the unique XTH gene product C terminus was excluded from the alignments).

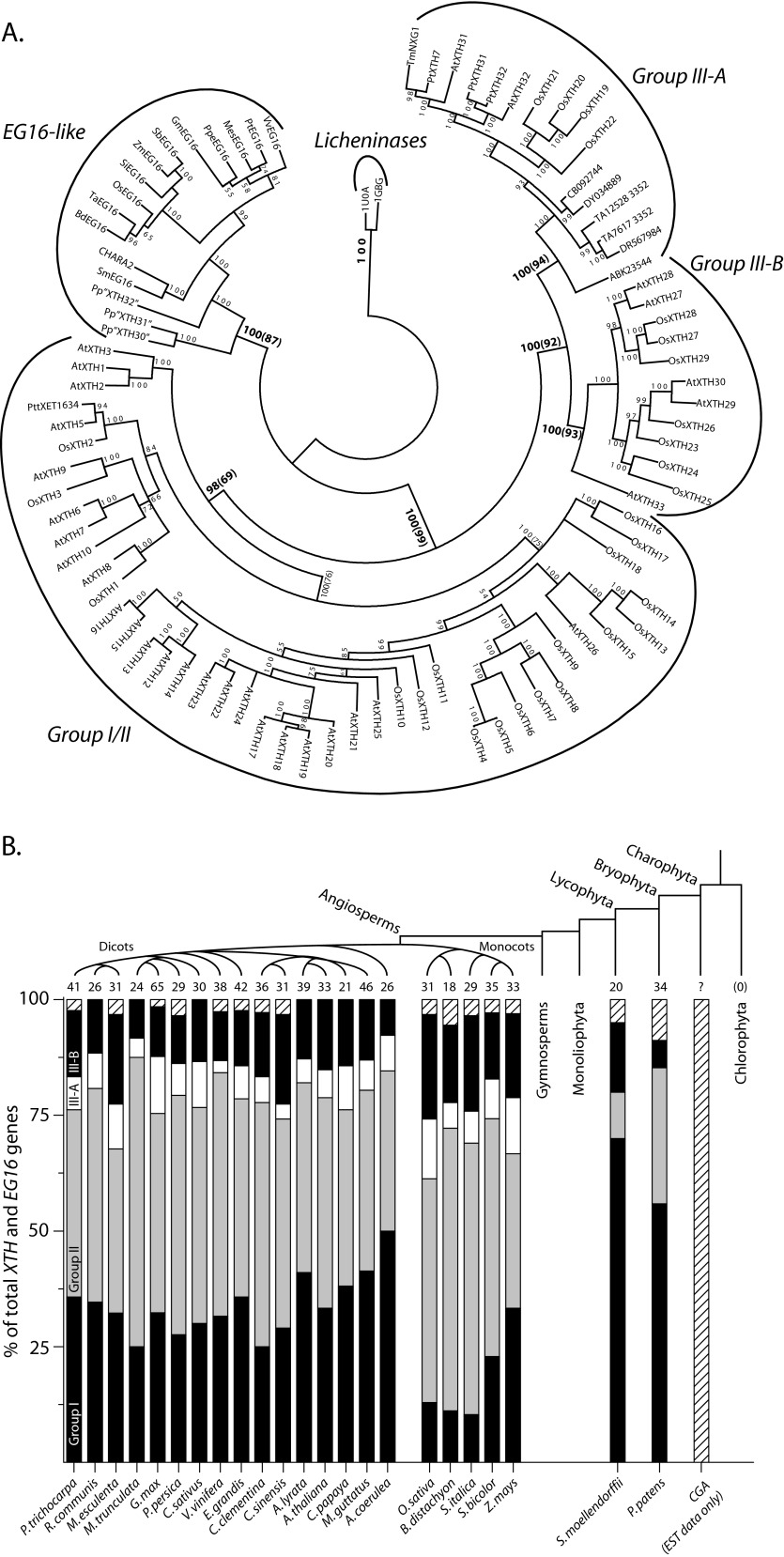

Notably, the inclusion of the PtEG16-like sequences in Bayesian and maximum likelihood phylogenies did not alter the overall relationships of the true XTH gene products observed previously (9, 11, 49, 50). Rather, PtEG16 and homologs formed a major distinct clade with strong statistical support (Fig. 2A). Relative tree branch lengths further indicated that this clade is intermediate between the true XTH gene products and their presumed bacterial ancestors, the licheninases (15). Monocot and dicot sequences are clearly separated in the tree, thus indicating a potential divergent evolution of PtEG16-like proteins in these two groups of flowering plants. A similar distinction can be seen among the hydrolytic Group III-A XTH gene products, where monocot, dicot, and non-angiosperm sequences cluster separately (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Phylogenetic relationship of PtEG16-like proteins in GH16 and census among plant proteomes. A, phylogenetic relationship of EG16s to XTH gene products and licheninases. XTH gene product groups are according to Ref. 11. The confidence at each node in the Bayesian tree is given in posterior probabilities from the Bayesian analysis multiplied by 100. At selected nodes, the bootstrap values from maximum likelihood calculations are indicated in parentheses. A. thaliana, O. sativa, and P. patens identifiers are according to Refs. 9 and 82). Specific EG16 sequence identifiers can be found in supplemental Table 2, and gymnosperm transcripts in Group III-A are denoted by their accession number at TIGR (24). B, occurrence of XTH Group, Group II, Group III-A, Group III-B, and PtEG16-like gene products (hatched) in selected plant in silico proteomes. The number of PtEG16-like members in charophycean green algal proteomes is presently unknown in the absence of genome data; however, corresponding transcripts have been tentatively identified (see “Results”).

A Census of PtEG16-like Proteins in Plants

After establishing that the PtEG16-like proteins formed a unique phylogenetic clade, we were then able to examine their presence or absence as a class within predicted plant proteomes available via Phytozome (51), thereby extending our previous census of Group I/II, III-A, and III-B XTH gene products (13). Although plants generally maintain large XTH gene families with tens of members, the PtEG16-like proteins occur in very limited numbers and are not found across all lineages (Fig. 2B). Notably, members of the clade containing PtEG16 are not found in the two chlorophytic algal genomes presently available; these genomes also lack XTH or licheninase-encoding genes. In the current absence of whole genome sequences, we were able to identify two partial expressed sequence tag sequences from charophycean green algae (Chara vulgaris CHARA2 (19) and C. nitellarum GenBankTM accession number HO204633 (52)) whose proteins appear to exhibit greater resemblance to PtEG16 than to true XTH gene products (supplemental Fig. S1 and Fig. 2A). These observations imply that PtEG16-like proteins may have first arisen in the charophytes.

Regardless, PtEG16-like proteins are conclusively found in an extant member of one of the oldest lineages of land plants, the moss Physcomitrella patens, which has three homologs. The lycophyte Selaginella moellendorfii, an early tracheophyte, contains only one PtEG16 homolog. Among the angiosperms, all available grass in silico proteomes (order Poales) likewise harbor one PtEG16 homolog each. The grass PtEG16 homologs are, however, distinguished by longer C termini, which nonetheless do not have significant similarity to the diagnostic C-terminal extensions of true XTH gene products (supplemental Fig. S1). Interestingly, PtEG16 homologs are not consistently found in dicotyledonous genomes. For example, they are missing in Medicago truncatula but are found in Glycine max; both are species within the Fabales. PtEG16 homologs are notably absent from the predicted proteomes of two Arabidopsis model species as well as other important dicots (Fig. 2B).

Biochemical Analysis Defines PtEG16 as a Broad Specificity Endo(xylo)glucanase

To elucidate the function of the P. trichocarpa POPTR_0002s15460 gene product, the protein was produced recombinantly in E. coli. Purification to homogeneity was achieved by immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography and subsequent gel filtration chromatography. The protein was then assayed for activity against typical polysaccharide substrates for the most closely related GH16 enzymes (i.e. the mixed linkage β(1→3)/β(1→4)-glucans from barley and Icelandic moss and the highly branched galactoxyloglucan from tamarind seed, as well as wheat arabinoxylan, lupin β-galactan, laminarin (a mixed linkage β(1→3)/β(1→6)-glucan), hydroxyethyl cellulose, and CMC).

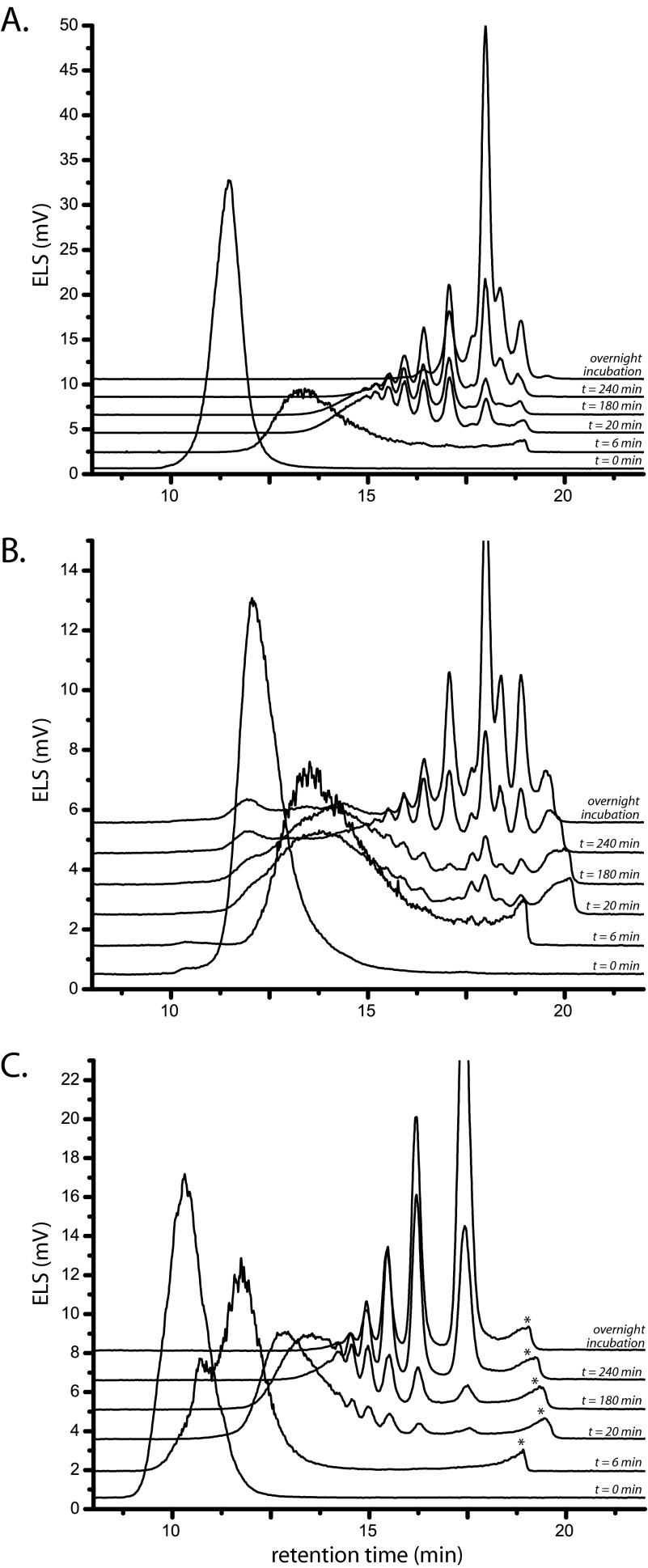

Initial activity screening of purified recombinant PtEG16 against these polysaccharides was unsuccessful. Closer inspection of the amino acid sequence and a tertiary structure homology model (see below) revealed that the 25-kDa protein had 11 cysteine residues, 5–7 of which were likely to be surface-exposed. Subsequently, we assayed the protein in the presence of DTT and analyzed polysaccharide depolymerization by gel permeation chromatography; the presence of the reducing agent effectively precluded the use of carbohydrate reducing end assays, such as the BCA assay (53) or the Nelson-Somogyi assay (54). In this way, the ability of PtEG16 to efficiently cleave barley β-glucan, Icelandic moss lichenan, and tamarind seed xyloglucan was clearly revealed (Fig. 3). In contrast, no change in polysaccharide molecular mass was observed under identical conditions for wheat arabinoxylan, lupin galactan, or laminarin, even after extensive incubation (24 h with 1 μm PtEG16; data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Time-dependent endohydrolytic cleavage of polysaccharides by PtEG16. The action of PtEG16 on barley β-glucan (A), Icelandic moss lichenin (B), and tamarind seed galactoxyloglucan (C) was analyzed using high performance size exclusion chromatography with evaporative light-scattering detection (ELS). The t = 0 trace corresponds to that of the corresponding polysaccharide before the addition of the enzyme. Compositional analyses of the oligosaccharide mixtures resulting from overnight incubation are shown in supplemental Figs. S3–S5. Peaks marked with an asterisk arise from low components the enzyme preparation (e.g. buffer and salts).

PtEG16 was also active on the artificial, soluble cellulose derivatives hydroxyethyl cellulose and CMC. The activity of PtEG16 on hydroxyethyl cellulose was complex; an initial rapid molecular mass shift was observed, followed by a much slower phase of limited degradation, which may indicate that only a few sites on this modified cellulose were susceptible to PtEG16-1 (supplemental Fig. S2). Analysis of CMC degradation was complicated by the observation that this polymer, as obtained from the supplier, was insoluble in the gel permeation chromatography eluent (100% DMSO). An overnight digest sample of CMC was, however, soluble in this solvent, which was indicative of reduction of the polymer molecular mass. HPAEC-PAD (data not shown) and MALDI-TOF MS (supplemental Fig. S3) analysis of this reaction subsequently revealed the presence of short cello-oligosaccharides and carboxymethylated derivatives.

Limit Digestion Products from Mixed Linkage Glucans

Further analysis of the products from overnight digestion of mixed linkage β(1→3)/β(1→4)-glucans and (galacto)xyloglucan using HPAEC-PAD and MALDI-TOF MS confirmed that PtEG16 is indeed a broad specificity endo-β(1→4)-glucanase. Upon extended incubation with the enzyme, barley β-glucan and laminarin were reduced to glucose, disaccharides (cellobiose/laminaribiose), and tetrasaccharides as predominant products (supplemental Fig. S4). Closer analysis of the tetrasaccharide peak resulting from either substrate (supplemental Fig. S4) indicated that this represented a single isomer with a retention time distinct from the available G4G4G3G, G3G4G4G, and G4G3G4G tetrasaccharide standards (where “G” represents Glc and the Arabic numeral represents a corresponding β(1→3) or β(1→4) glycosidic linkage). Considering the native polysaccharide structure (55), the other possible tetrasaccharide products from the mixed linkage glucans are cellotetraose (G4G4G4G) and G3G4G3G. Because the retention time of cellotetraose is shorter than the available mixed linkage tetrasaccharide standards under these HPAEC conditions (data not shown), we tentatively assign the observed product peak as G3G4G3G.

When explicitly tested for activity on the three commercially available mixed linkage tetraoses, PtEG16 only hydrolyzes the central β(1→4) linkage of G4G4G3G, thereby yielding G4G and G3G. This suggests that the possible modes for hydrolysis of the β(1→4) glucosidic bonds in G3G4↓G4↓G and G4↓G3G4↓G (potential cleavage sites indicated by arrows) are catalytically insignificant for these short substrates due to geometrical requirements (i.e. rejection of Glcβ(1→3) in subsites −1, −2, and −3) and/or a lack of a sufficient number of glucosyl units bound in the positive or negative enzyme subsites (see Ref. 56 for GH subsite nomenclature). Nonetheless, the production of G3G4G3G from mixed linkage glucans, as suggested above, would require acceptance of Glcβ(1→3) units in subsite −2. This implies that extended binding of polysaccharides in the active-site cleft may overcome such limitations. Regardless, the mode of action of PtEG16 on mixed linkage glucans appears distinct from that of archetypical GH16 licheninases, which explicitly require a β(1→3) linkage to span the −2 and −1 subsites to yield limit digestion products of the series G3G, G4G3G, G4G4G3G, and G4G4G4G3G (16).

Limit Digestion Products from Galactoxyloglucan

Despite a long incubation time, the hydrolysis of tamarind seed galactoxyloglucan by PtEG16 did not go to the same level of completion (supplemental Fig. S5) previously observed for plant and microbial XEHs (12, 18). In addition to the mixture of oligosaccharides expected from cleavage at the unbranched β(1→4)-linked glucosyl residues of the polysaccharide backbone (i.e. XXXG, XLXG, XXLG, and XLLG), a series consisting of longer oligosaccharide repeats was clearly observed by HPAEC-PAD (xyloglucooligosaccharide nomenclature is according to Ref. 57), where G represents Glcp or β-Glcp-(1→4), X is [α-Xylp-(1→6)]-β-Glcp-(1→4), and L is [β-Galp-(1→2)-α-Xylp-(1→6)]-β-Glcp-(1→4). Moreover, HPAEC-PAD and MALDI-TOF MS indicated that the ratio of the shortest oligosaccharide products deviated from the expected ratio of 1.4:1:3:5.4 XXXG/XLXG/XXLG/XLLG (58, 59). Specifically, the amount of the bis-galactosylated XLLG (Glc4Xyl3Gal2) appeared to be reduced (supplemental Fig. S5), which suggests that extended chain branches may limit hydrolysis.

Initial Rate Kinetics on Defined Xyloglucooligosaccharides and Cellooligosaccharides

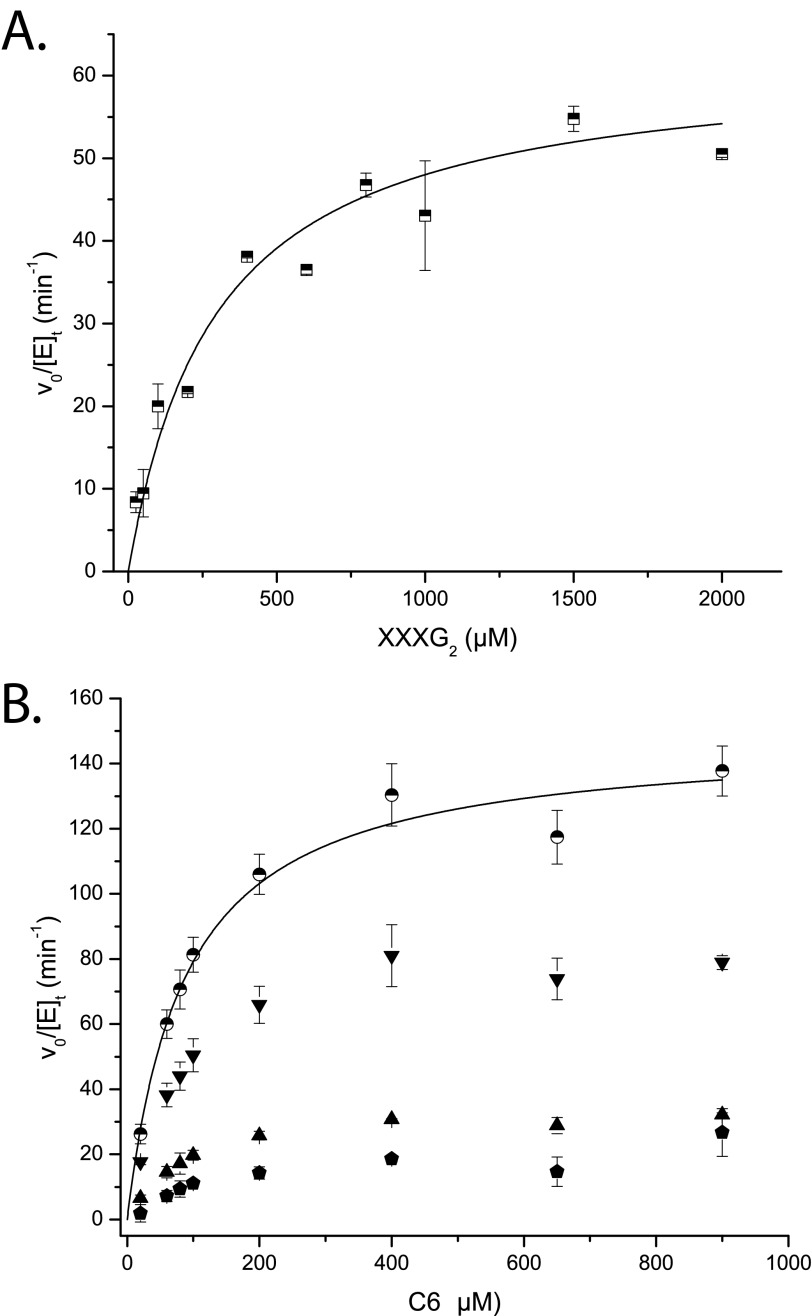

To further analyze the effect of polysaccharide branching on catalysis, we quantified the hydrolysis of well defined xylogluco- and cello-oligosaccharides by PtEG16 under initial rate kinetic conditions. The tetradecasaccharide XXXG↓XXXG was exclusively hydrolyzed at the internal, unbranched β(1→4)-linked glucosyl residue (cleavage site indicated by an arrow), with a kcat value of 62 ± 6 min−1 and a Km value of 295 ± 64 μm (Fig. 4A). Under these conditions of low substrate conversion, transglycosylation to form (XXXG)3 by disproportionation of the substrate was kinetically insignificant. However, after extended incubation of 1 mm XXXGXXXG with PtEG16, minor amounts of the transglycosylation products (XXXG)3–5 could be observed by HPAEC-PAD (supplemental Fig. S6A). In an independent assay, the heptasaccharide XXXG (Glc4Xyl3) was not hydrolyzed by PtEG16-1, thus providing further support that the enzyme can only cleave the glycosidic bond of non-xylosylated glucosyl units.

FIGURE 4.

Initial rate kinetic data for the PtEG16-catalyzed hydrolysis of oligosaccharides. A, rates of XXXG production from XXXGXXXG (XXXG2). B, rates of production of Glc4/Glc2 (inverted triangles), Glc3 (triangles), and Glc5/Glc (hexagons) from cellohexaose (C6; Glc6); circles represent the sum of rates for all cleavage modes. Error bars, S.E. from duplicate measurements. Lines represent the non-linear least-squares fits of the Michaelis-Menten equation to the data.

In contrast to the singular mode of cleavage of XXXGXXXG by the enzyme, unbranched cello-oligosaccharides gave rise to multiple products, which complicated initial rate kinetic analysis. The longest water-soluble cello-oligosaccharide, cellohexaose, produced Glc3 as well as pairwise equimolar amounts of Glc and Glc5, and Glc2 and Glc4 (Fig. 4B). The Glc2/Glc4 hydrolysis mode dominated, with a rate approximately equal to that of XXXGXXXG hydrolysis at saturation. Summation of all cellohexaose hydrolysis modes yielded a rate approximately twice that of XXXGXXXG at saturation (Fig. 4B). As with XXXGXXXG, extended incubation of cellopentaose with PtEG16-1 yielded apparent transglycosylation products (up to Glc11 in this case), as suggested by HPAEC-PAD (supplemental Fig. S6B).

Whereas the initial rate kinetics of cellohexaose were apparently uncomplicated by transglycosylation modes, this was not the case for cellopentaose and cellotetraose. For cellopentaose, a clear discrepancy in the rates of formation of Glc2 and Glc3 was observed across a range of initial substrate concentrations (supplemental Fig. S7A). Here, simple hydrolysis of either of the two indicated linkages, G4G4↓G4↓G4G4, would be expected to yield equimolar amounts of the products. The observation of a HPAEC peak with a retention time longer than cellohexaose (tentatively assigned as Glc7, in the absence of a standard sample) was further evidence for transglycosylation.

The initial rate kinetics observed for cellotetraose were likewise complicated, including the observation of increasing production of cellohexaose with increasing substrate concentration (supplemental Fig. S7B). Formation of this product is consistent with initial binding of cellotetraose in subsites −2 to +2, followed by cleavage to form a covalent, α-linked cellobiosyl enzyme intermediate, which is subsequently turned over by glycosyl transfer to a second molecule of cellotetraose. Of the shorter congeners, cellotriose was a very poor substrate, and cellobiose was not a substrate for PtEG16 (data not shown).

Analysis of Heterotransglycosylation Potential

In light of recent interest in the capacity of certain GH16 members and crude plant enzyme extracts to catalyze xyloglucan/β-glucan heterotransglycosylation (60, 61), we examined the reaction products from two representative glycosyl donor/acceptor substrate pairs by HPAEC-PAD. For the XXXGXXXG/cellobiose pair, the product distribution was identical to that of XXXGXXXG alone (i.e. only longer (XXXG)n products were observed (data not shown)). In the case of cellotetraose/XXXG, repeated analysis indicated the presence of very low abundance peaks, possibly corresponding to GXXG and GGXXXG, in addition to dominating hydrolysis and homotransglycosylation products (data not shown). However, the low amounts of these alternative products precluded isolation and definitive assignment, and we conclude that heterotransglycosylation is not kinetically significant for PtEG16.

Tertiary Structure of PtEG16 and Comparison with GH16 XEHs, XETs, and Licheninases

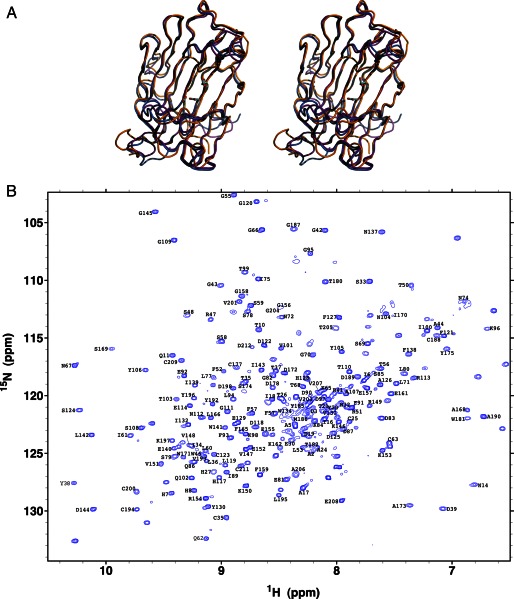

PtEG16 has thus far resisted crystallization.3 We therefore performed in silico structure homology modeling, supported by experimental protein NMR spectroscopic analyses, to obtain a three-dimensional representation of the enzyme. The M4T Server version 3.0 (62) selected a bacterial GH16 licheninase (PDB code 2ayh (63)) and a plant GH16 XEH (PDB code 2uwa (11)) as templates for modeling full-length PtEG16. For comparison, we also subjected PtEG16 to structural modeling using Protein Homology/Analogy Recognition Engine version 2.0 (Phyre2 (64)). Both approaches produced tertiary structures with a β-jellyroll fold typical of GH16 enzymes. Moreover, superimposition of the Cα traces indicated that these predicted structures were nearly identical (Fig. 5A; root mean square deviation values are given in supplemental Table S3).

FIGURE 5.

Modeling and experimental validation of the PtEG16 tertiary structure. A, superimposition of the M4T (marine) and Phyre2 (magenta) homology models and the chemical shift-derived CS23D (orange) model of PtEG16 in a wall-eyed stereo representation. Models are oriented with the positive enzyme subsites on the right, relative to the conserved active-site residues Glu-88, Asp-90, and Glu-92 (bottom to top) of PtEG16 (cf. Fig. 1). B, assigned 15N TROSY-HSQC spectrum of carbon-perdeuterated and 13C,15N-labeled PtEG16 in H2O buffer at pH 7.5 and 25 °C.

To provide experimental validation for the models, we investigated the recombinant PtEG16 using NMR spectroscopy. Under reducing conditions, the protein yielded an excellent quality, well dispersed 15N TROSY-HSQC spectrum with peak line widths indicative of a stably folded, monomeric protein (Fig. 5B). In total, of the 213 residues (not including the His6 tag), main chain 1HN, 15N, 13C′, 13Cα, and 13Cβ signals from 166 were unambiguously assigned via a manual analysis of standard triple resonance correlation experiments. An additional 14 spin systems were assigned using the PINE assignment server (65). Chemical shift assignments for only the 13C′, 13Cα, and 13Cβ nuclei were obtained for a further 29 residues (including 8 of the 11 prolines). Four residues were left without any assigned resonances (Pro-22, Pro-163, Gly-183, and Ser-213). The non-proline residues that are without amide proton and nitrogen assignments are located throughout the protein (supplemental Fig. S8). The lack of assignments may reflect spectral overlap, rapid amide hydrogen exchange, or conformational exchange broadening.

The NMR chemical shifts of main chain nuclei are sensitive indicators of protein secondary structure (66, 67). We therefore used the SPP (68), MICS (41), and TALOS+ (42) algorithms to determine the secondary structural elements of PtEG16 from the assigned chemical shifts. All three algorithms yielded similar results, identifying numerous β-strands with a limited number of short helical regions. Importantly, these secondary structural elements, derived from experimental data, agreed well with those present in the M4T structural model, as defined by VADAR (69) (supplemental Fig. S8).

Further experimental validation of the model was obtained by calculating the overall PtEG16 fold from backbone chemical shift data using the CS23D Web server (70). The resulting model superimposes very well the homology models from M4T and Phyre2 (Fig. 5A and supplemental Table S3). Moreover, superimposition with the M4T templates (licheninase (PDB code 2ayh) and XEH (PDB code 2uwa)), indicate that the PtEG16 models possess the canonical GH16 fold with a broader active-site cleft, which is typical of plant XTH gene products (supplemental Fig. S9 and Table S3; cf. Fig. 6).

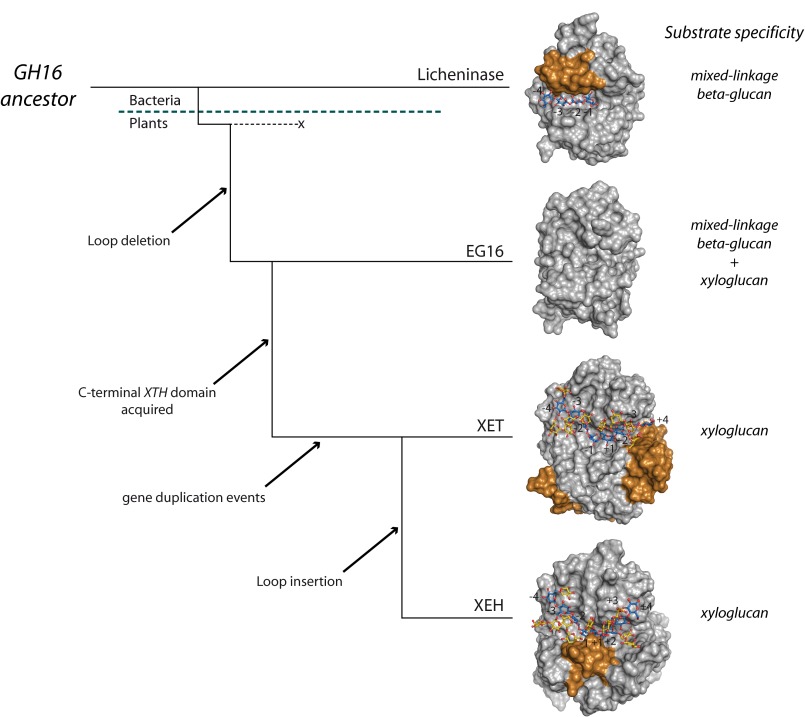

FIGURE 6.

Proposed evolution of EG16 and XTH gene products in GH16 from a licheninase-like ancestor. With reference to Fig. 1, the gold coloring represents the licheninase loop extension, the XET C-terminal extension, and the XEH YNIIG loop insertion in the respective proteins.

Inspection of these superimposed models indicates that this broadening of the active-site cleft has resulted from the deletion of a ∼12-amino acid sequence found in the bacterial licheninases (Fig. 1, residues 23–34). This loop extends into the concave face of the β-jellyroll to form a part of the negatively numbered enzyme subsites (supplemental Fig. S9A), thereby narrowing the active-site cleft (Fig. 6) and contributing many structural features necessary for specific recognition of kinked mixed linkage glucan chains (16, 48, 71). The removal of this loop in plant PtEG16 and XTH gene products is a clear prerequisite for the binding of highly branched xyloglucans (72–74).

In the positively numbered subsites, PtEG16 resembles a licheninase, primarily because it lacks the C-terminal extension characteristic of true XTH gene products (supplemental Fig. S9B). In XETs and XEHs, this motif elongates the substrate binding cleft by providing one β-sheet, narrows the positive subsites (Fig. 6), and supplies two-thirds of a Xyl +2′ xyloglucan specificity pocket that affects specificity (kcat/Km) 500-fold (72, 75). Like the licheninases, PtEG16 also lacks the small loop insertion immediately following the catalytic motif (NRT in PttXET16-34; Fig. 1), which further affects the structure of the positively numbered subsites in XTH gene products and also contains the conserved N-glycosylation site important for the stability of XTH Group I/II members (76, 77).

DISCUSSION

Barbeyron and colleagues (15, 78) were among the first to speculate upon the evolutionary basis of the diverse catalytic functionality observed among GH16 members. Although enzyme structure-function analyses continue to shed light on protein loop differences that fine-tune specificity for particular linear galactans and glucans among bacterial members (15, 79, 80), the evolutionary steps leading to the dramatic structural features of plant XTH gene products have remained essentially unknown.

Taken together, our present data suggest that a unique protein in black cottonwood, PtEG16, is a broad specificity glycoside hydrolase with nearly equal capacity to cleave linear glucans (mixed linkage β-glucans and cello-oligosaccharides) and highly branched xyloglucan oligo- and polysaccharides (e.g. Figs. 3 and 4). Moreover, this broad specificity appears to arise from a protein scaffold that is intermediate between extant bacterial licheninases and plant XTH gene products (Figs. 2 and 5). As such, these observations allow us to posit that PtEG16-like sequences represent an ancestral link in the evolution of extant plant XETs and XEHs.

Fig. 6 highlights a view of this potential evolution from the perspective of protein tertiary structure, supported by sequence-based phylogeny (Fig. 2A). In this scheme, an early GH16 ancestor with a structure similar to extant licheninases may have first given rise to a PtEG16-like protein via deletion of the licheninase-specific negative subsite loop. Although we cannot rigorously exclude the possibility that a PtEG16-like protein was the ancestor and that licheninases arose by loop addition, the apparent lack of direct PtEG16 homologs in the “lower” organisms, bacteria in particular, suggests otherwise.

The lack of this loop opened the active-site cleft and expanded the potential substrate range of PtEG16 homologs (Fig. 6). The observation of PtEG16 activity on both mixed linkage β-glucans and xyloglucan is particularly noteworthy, because these are the dominant matrix polysaccharides in grassy monocots and dicots, respectively. PtEG16 homologs are present in early plant lineages (Fig. 2B), and this dual activity would have thus poised them for subsequent functional adaptation in emerging species (6, 81) that favored either type of polysaccharide as a wall component. Single PtEG16 homologs are indeed found in many monocots and dicots (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, PtEG16-like genes, in particular in early diverging plants and monocots, have simple structures that lack introns, which may be further evidence of their bacterial origins (supplemental Table S2) (82).

Subsequently in the proposed evolution (Fig. 6), an early PtEG16 homolog is suggested to have acquired the large XTH C-terminal extension (Pfam XET_C, PF06955; Fig. 1), which is unique among GH16 members. This extension is found in all true XTH gene products from all major phylogenetic clades (Group I/II, III-A, and III-B; Fig. 2B), including all biochemically characterized XETs and XEHs (13). This suggests that acquisition of the C-terminal extension predated the massive expansion of XTH genes in mosses and later-diverging plants (Fig. 2B) (e.g. see Refs. 8, 9, and 82). The genetic mechanism of this acquisition is currently unknown.

Although systematic studies are lacking for most XTH gene products (13), it appears that at least some have lost much or all of their putative ancestors' ability to act upon mixed linkage β-glucans. Specifically, barley HvXET5 acts on barley mixed linkage β-glucan at ≤0.2% of its rate on xyloglucan, whereas nasturtium TmNXG1 (an XEH associated with seed storage polysaccharide hydrolysis) has no detectable activity on Icelandic moss lichenan or barley β-glucan (11). There is no a priori reason why XETs or XEHs should exclude unbranched β-glucans from their active-site clefts based on steric considerations. However, specific enzyme-substrate interactions have apparently been optimized to favor xyloglucan binding in these XTH gene products (11, 45, 72, 73, 75).

Finally, we have previously provided evidence that the comparatively small clade of Group III-A XTH gene products (Fig. 2A), which comprises predominant XEHs, arose from the larger body of XETs via the specific acquisition of two small loop insertions altering the active-site cleft topology (11, 13) (Fig. 6; cf. Fig. 1). Combined phylogenetic, biochemical, and tertiary structural analyses indicated that a 5-amino acid loop (YNIIG; Fig. 1) is a primary factor contributing to the predominant hydrolytic (XEH) capacity of nasturtium TmNXG1. Deletion of this loop significantly increased the transglycosylation/hydrolysis ratio of the enzyme, making it structurally and functionally more XET-like (11). This loop insertion is likewise found in two homologous A. thaliana XEHs of Group III-A (12).

In summary, the evolutionary scheme proposed here provides a new insight into the origins of the XTH gene products and a framework for the further exploration of protein structure-function relationships in plant GH16 members. Many questions remain outstanding, especially for PtEG16 homologs. These include the following.

To What Extent Can the Endoglucanase Designation Be Reliably Extended to Other PtEG16 Homologs?

We cautiously suggest that all members of the closely related dicot and monocot EG16-like clades may bear the same general activity profile as PtEG16 (Fig. 2A). However, the lack of demonstrable XET, XEH, or licheninase activity in one of three P. patens homologs (XTH32 (82)) suggests that careful functional analysis of early-diverging plant (moss) clades may especially be warranted.

What Is the in Vivo Role(s) of PtEG16 Homologs across Plant Lineages?

Although a comprehensive transcriptomic analysis has not been performed for any species, the gene encoding PtEG16 (previously known as XTH8) appears to be hormonally regulated (50). Likewise, a PpXTH32 promotor-glucuronidase fusion indicates tissue-specific expression in P. patens. The presence of single homologs in most species should facilitate reverse genetics analyses. Moreover, the lack of multiplication of PtEG16 homologs in plant genomes on a par with XTH genes may indicate either that they are functionally unique and under tight control or that they are simply molecular “transitional fossils,” vestigial sequences with no significant function. The observation that PtEG16 homologs are missing in many dicots might suggest the latter (Fig. 2A), although their functional importance may be inversely correlated with plant evolution. The lack of obvious signal peptides in PtEG16 homologs and a high abundance of Cys residues in some proteins (e.g. PtEG16), which may suggest intracellular localization, is particularly puzzling and relevant to this question.

What Is the Distribution and Function of PtEG16 and XTH Homologs in the Genomes of the Charophycean Green Algae?

Some members of this diverse group are the most primitive organisms known to have plantlike cell walls, including hemicellulosic polysaccharides like β(1→3)-glucans and xyloglucans (81). In notable contrast, the chlorophycean green algae do not possess xyloglucan (81) and, correspondingly, do not have any XTH-like genes (13) (Fig. 2B). We anticipate that forthcoming genomes of charophytes will illuminate the early origins of PtEG16 and XTH genes and their evolutionary relatedness.

In This Context, What Protein Structural Features Are Responsible for Substrate Specificity and Biochemical Function of PtEG16-like Proteins?

Our present homology models only allow reliable analysis of gross structural features on the level of overall fold and active site topology (Fig. 6). High resolution structural enzymology on par with that for other GH16 enzymes will be required to illuminate the details of substrate recognition and catalysis, which underpin biochemical and physiological function.

CONCLUSION

In harness, phylogenetic, biochemical, and protein structural analysis have revealed a unique clade of plant proteins in glycoside hydrolase family 16, whose members may represent a key step in the evolution of the widespread and diverse XTH gene family in plants. As such, the revelation of this clade will help refine future bioinformatics analyses of plant genomes. Moreover, further structural and functional analysis will undoubtedly bring new insight into the roles of individual clade members in the context of plant physiology.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in part, by grants from the Swedish Research Council and the Swedish Research Council Formas (to H. B.). Instrument and infrastructure support was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI), the British Columbia Knowledge Development Fund (BCKDF), the UBC Blusson Fund, and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1–S3 and Figs. S1–S9.

M. Czjzek, unpublished data.

- XTH

- xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolase

- XET

- xyloglucan:xyloglucosyl transferase

- XEH

- xyloglucan-specific endo-β-1,4-glucanase

- GH

- glycoside hydrolase

- GH16

- glycoside hydrolase family 16

- CMC

- carboxymethyl cellulose

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- HPAEC-PAD

- high performance anion exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection

- TROSY

- transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank.

REFERENCES

- 1. Carpita N., McCann M. (2000) The cell wall. in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Plants (Buchanan B., Gruissem W., Jones R., eds) pp. 52–108, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Somerset, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 2. Himmel M. E., Ding S. Y., Johnson D. K., Adney W. S., Nimlos M. R., Brady J. W., Foust T. D. (2007) Biomass recalcitrance. Engineering plants and enzymes for biofuels production. Science 315, 804–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ragauskas A. J., Williams C. K., Davison B. H., Britovsek G., Cairney J., Eckert C. A., Frederick W. J., Jr., Hallett J. P., Leak D. J., Liotta C. L., Mielenz J. R., Murphy R., Templer R., Tschaplinski T. (2006) The path forward for biofuels and biomaterials. Science 311, 484–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cosgrove D. J. (2005) Growth of the plant cell wall. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 850–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vogel J. (2008) Unique aspects of the grass cell wall. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 301–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fangel J. U., Ulvskov P., Knox J. P., Mikkelsen M. D., Harholt J., Popper Z. A., Willats W. G. (2012) Cell wall evolution and diversity. Front. Plant Sci. 3, 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Henrissat B., Coutinho P. M., Davies G. J. (2001) A census of carbohydrate-active enzymes in the genome of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 47, 55–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Geisler-Lee J., Geisler M., Coutinho P. M., Segerman B., Nishikubo N., Takahashi J., Aspeborg H., Djerbi S., Master E., Andersson-Gunnerås S., Sundberg B., Karpinski S., Teeri T. T., Kleczkowski L. A., Henrissat B., Mellerowicz E. J. (2006) Poplar carbohydrate-active enzymes. Gene identification and expression analyses. Plant Physiol. 140, 946–962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yokoyama R., Rose J. K., Nishitani K. (2004) A surprising diversity and abundance of xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolases in rice. Classification and expression analysis. Plant Physiol. 134, 1088–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Popper Z. A., Michel G., Hervé C., Domozych D. S., Willats W. G., Tuohy M. G., Kloareg B., Stengel D. B. (2011) Evolution and diversity of plant cell walls. From algae to flowering plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 62, 567–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baumann M. J., Eklöf J. M., Michel G., Kallas A. M., Teeri T. T., Czjzek M., Brumer H., 3rd (2007) Structural evidence for the evolution of xyloglucanase activity from xyloglucan endo-transglycosylases. Biological implications for cell wall metabolism. Plant Cell 19, 1947–1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kaewthai N., Gendre D., Eklöf J. M., Ibatullin F. M., Ezcurra I., Bhalerao R. P., Brumer H. (2013) Group III-A XTH genes of Arabidopsis thaliana encode predominant xyloglucan endo-hydrolases that are dispensable for normal growth. Plant Physiol. 161, 440–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eklöf J. M., Brumer H. (2010) The XTH gene family. An update on enzyme structure, function, and phylogeny in xyloglucan remodeling. Plant Physiol. 153, 456–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cantarel B. L., Coutinho P. M., Rancurel C., Bernard T., Lombard V., Henrissat B. (2009) The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy). An expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D233–D238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Michel G., Chantalat L., Duee E., Barbeyron T., Henrissat B., Kloareg B., Dideberg O. (2001) The κ-carrageenase of P. carrageenovora features a tunnel-shaped active site. A novel insight in the evolution of clan-B glycoside hydrolases. Structure 9, 513–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Planas A. (2000) Bacterial 1,3–1,4-β-glucanases. Structure, function, and protein engineering. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1543, 361–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davies G. J., Sinnott M. L. (2008) Sorting the diverse. The sequence-based classifications of carbohydrate-active enzymes. Biochem. J., doi: 10.1042/BJ20080382 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eklöf J. M., Ruda M. C., Brumer H. (2012) Distinguishing xyloglucanase activity in endo-β(1→4)glucanases. Methods Enzymol. 510, 97–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Van Sandt V. S., Stieperaere H., Guisez Y., Verbelen J. P., Vissenberg K. (2007) XET activity is found near sites of growth and cell elongation in bryophytes and some green algae. New insights into the evolution of primary cell wall elongation. Ann. Bot. 99, 39–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bendtsen J. D., Nielsen H., von Heijne G., Brunak S. (2004) Improved prediction of signal peptides. SignalP 3.0. J. Mol. Biol. 340, 783–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Emanuelsson O., Nielsen H., von Heijne G. (1999) ChloroP, a neural network-based method for predicting chloroplast transit peptides and their cleavage sites. Protein Sci. 8, 978–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Juncker A. S., Willenbrock H., Von Heijne G., Brunak S., Nielsen H., Krogh A. (2003) Prediction of lipoprotein signal peptides in Gram-negative bacteria. Protein Sci. 12, 1652–1662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hamby S. E., Hirst J. D. (2008) Prediction of glycosylation sites using random forests. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Childs K. L., Hamilton J. P., Zhu W., Ly E., Cheung F., Wu H., Rabinowicz P. D., Town C. D., Buell C. R., Chan A. P. (2007) The TIGR plant transcript assemblies database. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, D846–D851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Edgar R. C. (2004) MUSCLE. Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hall T. A. (1999) BioEdit. A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41, 95–98 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guindon S., Gascuel O. (2003) A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 52, 696–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huelsenbeck J. P., Ronquist F. (2001) MrBayes. Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17, 754–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. (2007) MEGA4. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1596–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Oganesyan N., Kim S. H., Kim R. (2005) On-column protein refolding for crystallization. J. Struct. Funct. Genomics 6, 177–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Czisch M., Boelens R. (1998) Sensitivity enhancement in the TROSY experiment. J. Magn. Reson. 134, 158–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meissner A., Schulte-Herbruggen T., Briand J., Sørensen O. W. (1998) Double spin-state-selective coherence transfer. Application for two-dimensional selection of multiplet components with long transverse relaxation times. Mol. Phys. 95, 1137–1142 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weigelt J. (1998) Single scan, sensitivity- and gradient-enhanced TROSY for multidimensional NMR experiments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 10778–10779 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rance M., Loria J. P., Palmer A. G. (1999) Sensitivity improvement of transverse relaxation-optimized spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 136, 92–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhu G., Kong X. M., Sze K. H. (1999) Gradient and sensitivity enhancement of 2D TROSY with water flip-back, 3D NOESY-TROSY and TOCSY-TROSY experiments. J. Biomol. NMR 13, 77–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Eletsky A., Kienöfer A., Pervushin K. (2001) TROSY NMR with partially deuterated proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 20, 177–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Salzmann M., Wider G., Pervushin K., Senn H., Wüthrich K. (1999) TROSY-type triple-resonance experiments for sequential NMR assignments of large proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 844–848 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Salzmann M., Pervushin K., Wider G., Senn H., Wüthrich K. (1998) TROSY in triple-resonance experiments. New perspectives for sequential NMR assignment of large proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 13585–13590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995) NMRPipe. A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Godard T., Kneller D. G. (2008) SPARKY version 3.115, University of California, San Francisco [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shen Y., Bax A. (2012) Identification of helix capping and β-turn motifs from NMR chemical shifts. J. Biomol. NMR 52, 211–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shen Y., Delaglio F., Cornilescu G., Bax A. (2009) TALOS+. A hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J. Biomol. NMR 44, 213–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Camilloni C., De Simone A., Vranken W. F., Vendruscolo M. (2012) Determination of secondary structure populations in disordered states of proteins using nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shifts. Biochemistry 51, 2224–2231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Campbell P., Braam J. (1999) In vitro activities of four xyloglucan endotransglycosylases from Arabidopsis. Plant J. 18, 371–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Johansson P., Brumer H., 3rd, Baumann M. J., Kallas A. M., Henriksson H., Denman S. E., Teeri T. T., Jones T. A. (2004) Crystal structures of a poplar xyloglucan endotransglycosylase reveal details of transglycosylation acceptor binding. Plant Cell 16, 874–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bateman A., Coin L., Durbin R., Finn R. D., Hollich V., Griffiths-Jones S., Khanna A., Marshall M., Moxon S., Sonnhammer E. L., Studholme D. J., Yeats C., Eddy S. R. (2004) The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D138–D141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hahn M., Pons J., Planas A., Querol E., Heinemann U. (1995) Crystal structure of Bacillus licheniformis 1,3–1,4-β-d-glucan 4-glucanohydrolase at 1.8 Å resolution. FEBS Lett. 374, 221–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gaiser O. J., Piotukh K., Ponnuswamy M. N., Planas A., Borriss R., Heinemann U. (2006) Structural basis for the substrate specificity of a Bacillus 1,3–1,4-β-glucanase. J. Mol. Biol. 357, 1211–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Del Bem L. E., Vincentz M. G. (2010) Evolution of xyloglucan-related genes in green plants. BMC Evol. Biol. 10, 341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ye X., Yuan S. H., Guo H., Chen F., Tuskan G. A., Cheng Z. M. (2012) Evolution and divergence in the coding and promoter regions of the Populus gene family encoding xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolases. Tree Genet. Genomes 8, 177–194 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Goodstein D. M., Shu S., Howson R., Neupane R., Hayes R. D., Fazo J., Mitros T., Dirks W., Hellsten U., Putnam N., Rokhsar D. S. (2012) Phytozome. A comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1178–D1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sørensen I., Pettolino F. A., Bacic A., Ralph J., Lu F., O'Neill M. A., Fei Z. Z., Rose J. K., Domozych D. S., Willats W. G. (2011) The charophycean green algae provide insights into the early origins of plant cell walls. Plant J. 68, 201–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McFeeters R. F. (1980) A manual method for reducing sugar determinations with 2,2′-bicinchoninate reagent. Anal. Biochem. 103, 302–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nelson N. (1944) A photometric adaptation of the Somogyi method for the determination of glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 153, 375–380 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Burton R. A., Fincher G. B. (2009) (1,3;1,4)-β-d-Glucans in cell walls of the poaceae, lower plants, and fungi. A tale of two linkages. Mol. Plant. 2, 873–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Davies G. J., Wilson K. S., Henrissat B. (1997) Nomenclature for sugar-binding subsites in glycosyl hydrolases. Biochem. J. 321, 557–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fry S. C., York W. S., Albersheim P., Darvill A., Hayashi T., Joseleau J. P., Kato Y., Lorences E. P., Maclachlan G. A., McNeil M., Mort A. J., Reid J. S., Seitz H. U., Selvendran R. R., Voragen A. G., White A. R. (1993) An unambiguous nomenclature for xyloglucan-derived oligosaccharides. Physiol. Plant. 89, 1–3 [Google Scholar]

- 58. York W. S., Harvey L. K., Guillen R., Albersheim P., Darvill A. G. (1993) The structure of plant-cell walls. 36. Structural-analysis of tamarind seed xyloglucan oligosaccharides using β-galactosidase digestion and spectroscopic methods. Carbohydr. Res. 248, 285–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. York W. S., Impallomeni G., Hisamatsu M., Albersheim P., Darvill A. G. (1995) 11 newly characterized xyloglucan oligoglycosyl alditols. The specific effects of side-chain structure and location on H-1-NMR chemical-shifts. Carbohydr. Res. 267, 79–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hrmova M., Farkas V., Lahnstein J., Fincher G. B. (2007) A barley xyloglucan xyloglucosyl transferase covalently links xyloglucan, cellulosic substrates, and (1,3;1,4)-β-d-glucans. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 12951–12962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mohler K. E., Simmons T. J., Fry S. C. (2013) Mixed-linkage glucan:xyloglucan endotransglucosylase (MXE) re-models hemicelluloses in Equisetum shoots but not in barley shoots or Equisetum callus. New Phytol. 197, 111–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fernandez-Fuentes N., Madrid-Aliste C. J., Rai B. K., Fajardo J. E., Fiser A. (2007) M4T. A comparative protein structure modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W363–W368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hahn M., Keitel T., Heinemann U. (1995) Crystal and molecular-structure at 0.16 nm resolution of the hybrid Bacillus endo-1,3–1,4-β-d-glucan 4-glucanohydrolase H (A16-M). Eur. J. Biochem. 232, 849–858 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kelley L. A., Sternberg M. J. (2009) Protein structure prediction on the Web. A case study using the Phyre server. Nat. Protoc. 4, 363–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bahrami A., Assadi A. H., Markley J. L., Eghbalnia H. R. (2009) Probabilistic interaction network of evidence algorithm and its application to complete labeling of peak lists from protein NMR spectroscopy. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wishart D. S., Sykes B. D., Richards F. M. (1991) Relationship between nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shift and protein secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 222, 311–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wishart D. S., Sykes B. D. (1994) The 13C chemical-shift index. A simple method for the identification of protein secondary structure using 13C chemical-shift data. J. Biomol. NMR 4, 171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Marsh J. A., Singh V. K., Jia Z., Forman-Kay J. D. (2006) Sensitivity of secondary structural propensities to sequence differences between α- and γ-synuclein. Implications for fibrillation. Protein Sci. 15, 2795–2804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Willard L., Ranjan A., Zhang H., Monzavi H., Boyko R. F., Sykes B. D., Wishart D. S. (2003) VADAR. A Web server for quantitative evaluation of protein structure quality. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3316–3319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wishart D. S., Arndt D., Berjanskii M., Tang P., Zhou J., Lin G. (2008) CS23D. A Web server for rapid protein structure generation using NMR chemical shifts and sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W496–W502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Chen J. H., Tsai L. C., Huang H. C., Shyur L. F. (2010) Structural and catalytic roles of amino acid residues located at substrate-binding pocket in Fibrobacter succinogenes 1,3–1,4-β-d-glucanase. Proteins 78, 2820–2830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Mark P., Baumann M. J., Eklöf J. M., Gullfot F., Michel G., Kallas A. M., Teeri T. T., Brumer H., Czjzek M. (2009) Analysis of nasturtium TmNXG1 complexes by crystallography and molecular dynamics provides detailed insight into substrate recognition by family GH16 xyloglucan endo-transglycosylases and endo-hydrolases. Proteins 75, 820–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mark P., Zhang Q., Czjzek M., Brumer H., Agren H. (2011) Molecular dynamics simulations of a branched tetradecasaccharide substrate in the active site of a xyloglucan endo-transglycosylase. Mol. Simul. 37, 1001–1013 [Google Scholar]

- 74. Addington T., Calisto B., Alfonso-Prieto M., Rovira C., Fita I., Planas A. (2011) Re-engineering specificity in 1,3–1,4-β-glucanase to accept branched xyloglucan substrates. Proteins 79, 365–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Saura-Valls M., Fauré R., Brumer H., Teeri T. T., Cottaz S., Driguez H., Planas A. (2008) Active-site mapping of a Populus xyloglucan endo-transglycosylase with a library of xylogluco-oligosaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 21853–21863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Campbell P., Braam J. (1998) Co- and/or post-translational modifications are critical for TCH4 XET activity. Plant J. 15, 553–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kallas A. M., Piens K., Denman S. E., Henriksson H., Fäldt J., Johansson P., Brumer H., Teeri T. T. (2005) Enzymatic properties of native and deglycosylated hybrid aspen (Populus tremula x tremuloides) xyloglucan endotransglycosylase 16A expressed in Pichia pastoris. Biochem. J. 390, 105–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Barbeyron T., Gerard A., Potin P., Henrissat B., Kloareg B. (1998) The κ-carrageenase of the marine bacterium Cytophaga drobachiensis. Structural and phylogenetic relationships within family-16 glycoside hydrolases. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15, 528–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hehemann J. H., Correc G., Barbeyron T., Helbert W., Czjzek M., Michel G. (2010) Transfer of carbohydrate-active enzymes from marine bacteria to Japanese gut microbiota. Nature 464, 908–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Hehemann J. H., Correc G., Thomas F., Bernard T., Barbeyron T., Jam M., Helbert W., Michel G., Czjzek M. (2012) Biochemical and Structural Characterization of the complex agarolytic enzyme system from the marine bacterium Zobellia galactanivorans. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 30571–30584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Domozych D. S., Ciancia M., Fangel J. U., Mikkelsen M. D., Ulvskov P., Willats W. G. (2012) The cell walls of green algae. A journey through evolution and diversity. Front. Plant Sci. 3, 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Yokoyama R., Uwagaki Y., Sasaki H., Harada T., Hiwatashi Y., Hasebe M., Nishitani K. (2010) Biological implications of the occurrence of 32 members of the XTH (xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase) family of proteins in the bryophyte Physcomitrella patens. Plant J. 64, 645–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Gouet P., Robert X., Courcelle E. (2003) ESPript/ENDscript. Extracting and rendering sequence and 3D information from atomic structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3320–3323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.