Background: AcnR is an aconitase repressor in the biotechnologically important bacterium Corynebacterium glutamicum.

Results: Citrate-Mg2+ occupies a non-canonical ligand site and lowers the DNA affinity of AcnR.

Conclusion: AcnR is regulated by citrate-Mg2+ through a non-canonical binding site.

Significance: AcnR is the first TetR member with potentially two independent ligand binding sites. Identification of citrate-Mg2+ as a ligand is crucial for understanding its physiological role.

Keywords: Crystal Structure, Gene Regulation, Ligand-binding Protein, Metabolic Regulation, Structural Biology, Transcription Regulation, Corynebacteriales

Abstract

Corynebacterium glutamicum is an important industrial bacterium as well as a model organism for the order Corynebacteriales, whose citric acid cycle occupies a central position in energy and precursor supply. Expression of aconitase, which isomerizes citrate into isocitrate, is controlled by several transcriptional regulators, including the dimeric aconitase repressor AcnR, assigned by sequence identity to the TetR family. We report the structures of AcnR in two crystal forms together with ligand binding experiments and in vivo studies. First, there is a citrate-Mg2+ moiety bound in both forms, not in the canonical TetR ligand binding site but rather in a second pocket more distant from the DNA binding domain. Second, the citrate-Mg2+ binds with a KD of 6 mm, within the range of physiological significance. Third, citrate-Mg2+ lowers the affinity of AcnR for its target DNA in vitro. Fourth, analyses of several AcnR point mutations provide evidence for the possible involvement of the corresponding residues in ligand binding, DNA binding, and signal transfer. AcnR derivatives defective in citrate-Mg2+ binding severely inhibit growth of C. glutamicum on citrate. Finally, the structures do have a pocket corresponding to the canonical tetracycline site, and although we have not identified a ligand that binds there, comparison of the two crystal forms suggests differences in the region of the canonical pocket that may indicate a biological significance.

Introduction

Corynebacterium glutamicum is a non-pathogenic, predominantly aerobic Gram-positive soil bacterium that can excrete glutamate (1) and is used industrially for the large scale production of amino acids, in particular l-glutamate (about 2.16 million tons/year) and l-lysine (about 1.48 million tons/year). Because the world market for amino acids is continuously increasing, there are ongoing efforts to improve production strains and processes (2). C. glutamicum has also gained interest as a model organism for the order Corynebacteriales, which includes the human pathogens Corynebacterium diphtheriae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. A wealth of knowledge on C. glutamicum has been summarized in a handbook (3) and two monographs (4, 5). The citric acid (tricarboxylic acid, TCA)5 cycle of C. glutamicum has been studied intensively because of its importance in energy metabolism and in the production of the amino acid precursors oxaloacetate and 2-oxoglutarate (6, 7). Because substrate carbon is lost as carbon dioxide in the TCA cycle, regulation of the carbon flux through this cycle is of special interest for biotechnological production processes. AcnR was identified as the first transcriptional regulator of a TCA cycle enzyme in C. glutamicum and functions as a repressor of acn, which is to date its only known target gene (8). AcnR is conserved in all corynebacteria and mycobacteria and binds as a dimer to an imperfect inverted repeat (5′-CAGAACGCTTGTACTG-3′) located within the −10/−35 region of the acn promoter. Comparison with the acn promoter region of other species identified a consensus binding motif (CAGNACnnncGTACTG). An acnR deletion mutant grows slightly faster than the wild type on glucose or acetate minimal medium and has an increased aconitase activity (5.3-fold higher on glucose and 1.9-fold higher on acetate). When cultivated in a medium with a low iron content, overproduction of aconitase in the acnR mutant causes iron limitation (8).

Aconitase is the second enzyme in the TCA cycle and catalyzes the stereospecific isomerization of citrate to isocitrate via cis-aconitate (9, 10) and is also involved in the glyoxylate and the methylcitrate cycles (6). In the latter, it catalyzes the conversion of 2-methylaconitate to 2-methylisocitrate. In contrast to organisms such as Escherichia coli (11), C. glutamicum possesses only a single aconitase containing a [4Fe-4S] cluster, which is crucial for catalytic activity and which is highly oxygen-sensitive (10, 12). Previous studies revealed that the flux through the TCA cycle (13) as well as the aconitase activity differs significantly in cells grown on different carbon sources (aconitase activity on glucose, 0.20 ± 0.05 unit mg−1; propionate, 0.47 ± 0.13 unit mg−1; citrate, 0.53 ± 0.08 unit mg−1; acetate, 0.82 ± 0.08 unit mg−1), suggesting that the aconitase reaction might represent a rate-limiting step in this cycle (8). In addition, an aconitase deletion mutant faces strong selection pressure to lose citrate synthase activity, probably caused by high intracellular citrate concentrations (12). This explains the tight regulation of acn in C. glutamicum by at least four different regulators, AcnR, RipA (14), RamA (15), and GlxR (16). RipA is part of the iron homeostasis control system and represses transcription of acn under iron starvation conditions (17). Activation of acn transcription by RamA during growth on acetate is probably required to allow for an increased flux through the TCA cycle on this substrate (13, 18). The cAMP sensor GlxR is a global transcriptional regulator that controls at least 150 genes in a broad functional context (19, 20) with a function in global coordination of metabolism.

AcnR belongs to the TetR family of dimeric transcriptional regulators (21), whose members contain an N-terminal DNA-binding domain (DBD) and a C-terminal dimerization and ligand-binding domain (LBD) (22). Although there are large differences in the LBD, which allow for the response to different ligands, the sequence and structure of the DBD are highly conserved. Although several three-dimensional structures of TetR-type regulators have been determined, there are only four examples where all three functional forms (free protein, complex with operator, and complex with effector) are known: E. coli TetR (23, 24), Staphylococcus aureus QacR (25, 26), C. glutamicum CgmR (27, 28), and Streptomyces antibioticus SimR (29, 30). It is assumed that binding of a ligand to the LBD causes AcnR to be released from the DNA, allowing the expression of the aconitase gene. Although a large number of putative effector compounds were tested, no ligand of AcnR was identified in previous studies (8).

Current structures of TetR family proteins reveal the evolution of two different types of binding pockets. In the first, the two symmetric subunits contribute to form a single large pocket, whereas the second contains two independent symmetrically located smaller pockets, one within each subunit. This latter site, where tetracycline binds in TetR, we will refer to as the canonical site. The nature of the ligand is critical for understanding the regulatory mechanism and physiological function of AcnR, and we initiated structural studies with the aim of establishing its identity (31). Here, we present crystal structures of AcnR showing that citrate-Mg2+ binds to a quite different non-canonical pocket. The affinity of the citrate-Mg2+, measured using surface plasmon resonance, is shown to be within the biologically relevant range. The presence of Mg2+ is strictly required for citrate binding to AcnR, which significantly lowers the affinity of AcnR for DNA. Although AcnR does contain a bigger canonical pocket similar to that of the tetracycline site in TetR, this site is empty in our structures. Finally, we relate the properties of a set of AcnR variants to our structural and biochemical studies.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Growth Media

All strains and plasmids used are listed in supplemental Table S1. For plasmid-harboring strains, the medium was supplemented with 25 mg liter−1 (C. glutamicum) or 50 mg liter−1 (E. coli) kanamycin. For induction of target genes cloned into the expression plasmid pEKEx2 or pAN6, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was used in concentrations as specified. For cloning purposes, E. coli DH5α was used and grown at 37 °C in lysogeny broth (LB) (32).

Recombinant DNA

The enzymes for recombinant DNA work were obtained from New England Biolabs (Frankfurt, Germany) or Fermentas (St. Leon-Rot, Germany). The oligonucleotides were obtained from Operon (Cologne, Germany) and are listed in supplemental Table S2. Routine methods such as PCR, restriction, and ligation were performed using standard protocols (32). Chromosomal DNA of C. glutamicum was prepared as described previously (33). E. coli plasmids were isolated using the QIAprep spin miniprep kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). E. coli was transformed using the RbCl method (34).

The plasmid pET-TEV-AcnR was constructed as follows. The AcnR coding region was amplified by PCR using the oligonucleotides acnR-Krist-for-NdeI and acnR-Krist-rev-XhoI and chromosomal DNA of C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 as template. After digestion with NdeI and XhoI, the PCR product was cloned into the expression vector pET-TEV cut with the same restriction enzymes. The pET-TEV-AcnR-encoded AcnR derivative contained 29 additional N-terminal amino acids (MGSSHHHHHHHHHHDYDIPTTENLYFQGH), of which, after cleavage with tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease, only three additional amino acids (GHM) remained at the N terminus.

The plasmid pET-TEV-MtAcnR was constructed according to pET-TEV-AcnR, using the oligonucleotides Mt_AcnR_NdeI_fw and Mt_AcnR_XhoI_rv and chromosomal DNA of M. tuberculosis strain H37rv as template. For the plasmid pMal-c-MtAcnR, the acnR gene of M. tuberculosis and the codons of the TEV cleavage site were amplified using the oligonucleotides TEV-site-Eco-fw and Mt_AcnR_XbaI_rv and the plasmid pET-TEV-MtAcnR as template. After digestion with EcoRI and XbaI, the PCR product was cloned into the plasmid pMal-c cut with the same restriction enzymes. The MtAcnR derivative encoded by this plasmid contains the maltose-binding protein of E. coli at its N terminus, which can be cleaved off by TEV protease as described above.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Plasmids which code for C. glutamicum AcnR variants with single amino acid exchanges (C23A, K43A, K55A, E65A, D66A, R69A, M70A, M86A, R92A, W95A, R99A, K104A, D119A, R130A, R141A, D143A, D158A, E181A, and R185A) were constructed with the QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) using the plasmids pEKEx2-acnR-C-Strep or pET-TEV-AcnR as template and the oligonucleotides listed in supplemental Table S2. pEKEx2-acnR-C-Strep is an E. coli/C. glutamicum shuttle plasmid and allows overproduction of an AcnR derivative containing 10 additional C-terminal amino acids (LEWSHPQFEK), including a StrepTag-II sequence. The StrepTag-II allows for affinity purification of AcnR by StrepTactin affinity chromatography (35).

Overproduction and Purification of AcnR and Mutated Variants by Nickel Chelate Affinity Chromatography

This was carried out as described earlier (31). In contrast to our earlier studies (8), tag-free AcnR was used here for all experiments because (i) AcnR proved to be more stable over longer time periods without the tag; (ii) although the tag did not interfere with DNA binding, it might influence ligand binding to AcnR; and (iii) crystallization trials with His-tagged AcnR were not successful.

Purification of AcnR and Variants by StrepTactin Affinity Chromatography

Overexpression and purification were performed as described previously (36). Subsequently, gel filtration was performed with a SuperdexTM 200 10/300 GL column connected to an ÄktaTM FPLC system using the same buffer as for the His tag derivative. The mutant derivatives of AcnR were concentrated to 0.07–0.27 mg ml−1 and stored frozen as for the wild-type protein.

Purification of MtAcnR by Maltose-binding Protein Affinity Chromatography

Overexpression using the plasmid pMal-c-MtAcnR was performed as described for pET-TEV-AcnR except that after induction, the cells were further cultivated at 15 °C overnight. The cells from 50 ml of culture were resuspended in 4 ml of buffer M (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mm NaCl)/g of cells, and protease inhibitor was added (10 μl each of 100 mm phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride and 100 mm diisopropyl fluorophosphates per ml of cell suspension). Cell disruption and cell extract preparation were performed as described above. An amylose resin (New England Biolabs) column with a bed volume of 5 ml was equilibrated with buffer M. The cell extract was applied onto the column, followed by washing with 20 ml of buffer M. Elution was performed with buffer M additionally containing 10 mm maltose.

Crystallization, Data Collection, and Structure Solution

AcnR was crystallized as described previously (31). In brief, crystals were obtained with protein concentrated at 26.5 mg ml−1 incubated with 5 mm sodium citrate and 5 mm MgCl2 and set up in 300 + 300-μl drops of 1 m ammonium phosphate, 100 mm sodium citrate, pH 4, and optimized. Data were collected on two native crystals, one on beamline I02 at the Diamond Light Source and another on beamline ID-29 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF). Integration and scaling of the images with iMOSFLM (37, 38) and SCALA (39) revealed that there were two crystal forms, both in Laue group Pmmm, which differ by a doubling of the c axis in Form II. Subsequent calculations were carried out with programs from the CCP4 suite (40) unless otherwise indicated. Form I is in space group P21212 with data to 1.9 Å spacing with one protomer per asymmetric unit, and Form II is in P212121 with data to 1.6 Å with a dimer in the asymmetric unit. The two independent protomers in the Form II crystal have significant conformational differences in the canonical pocket (see below).

A heavy atom derivative was obtained (31) using 2 mm KAu(CN)2. Data were collected to 2.55 Å resolution on beamline ID14-1 at the ESRF and processed using HKL2000 (41). The derivative was isomorphous with the Form I native. The structure was solved by SAD with SHELXC/D/E (42), and automatic model building with BUCCANEER (43) gave 90% of the residues. Rebuilding and refinement were done with COOT (44) and REFMAC (45) to final Rwork/Rfree of 19.4/26.3%.

The resulting model was used for the refinement of Form I and for molecular replacement using PHASER (46) to solve the native Form II. The protein was modeled for residues ∼11–187, with the last visible residue at each end varying slightly between the three crystals. The Form I and II native models were refined to Rwork/Rfree of 19.4/24.6% and 14.1/20.5%, respectively. For all three structures, all residues are in the allowed region of the Ramachandran plot (47). A summary of the data and refinement statistics is shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

Values in parenthesis correspond to the high resolution shell.

| Au derivative | Native Form I | Native Form II | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| Source | ESRF | ESRF | Diamond Light Source |

| Beamline | ID14–1 | ID-29 | I02 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9334 | 1.0032 | 0.9795 |

| Space group | P21212 | P21212 | P212121 |

| Cell dimensions a, b, c (Å) | 34.14, 72.88, 73.25 | 34.64, 72.73, 73.20 | 34.21, 72.79, 145.57 |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.54 (2.58-2.54) | 1.9 (2.00-1.90) | 1.65 (1.74-1.65) |

| Rmerge | 0.073 (0.149) | 0.137 (0.658) | 0.082 (0.436) |

| I/σI | 47.9 (21.9) | 10.0 (3.6) | 9.4 (2.7) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) | 99.3 (99.9) | 99.6 (99.2) |

| Redundancy | 8.8 (8.4) | 6.0 (6.2) | 4.5 (4.5) |

| Refinement | |||

| No. of unique reflections | 6461 | 14,286 | 44,662 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 19.8/26.3 | 19.4/24.6 | 14.15/20.48 |

| Protein residues | 176 | 174 | 354 |

| Residues modeled | 11-186 | 13-186 | A, 11-186; B, 11-187 |

| Ligand/ion | 4 | 2 | 9 |

| Water | 49 | 102 | 353 |

| B-factors (Å2) | |||

| Protein | 21.5 | 27.9 | 20.8 |

| Ligand/ion | 32.2 | 23.0 | 22.8 |

| Water | 24.5 | 37.8 | 37.4 |

| r.m.s. deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.016 | 0.019 | 0.021 |

| Bond angles (degrees) | 1.355 | 1.956 | 1.620 |

| Ramachadran plot (%) | |||

| Preferred regions | 97.70 | 98.81 | 97.89 |

| Allowed regions | 2.3 | 1.19 | 2.11 |

| Outliers | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Protein Data Bank codes | 4AC6 | 4AF5 | 4ACI |

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

The binding of AcnR or variants to the acn promoter of C. glutamicum was tested. A 340-bp DNA fragment covering the acn promoter region was amplified by PCR using chromosomal DNA of the C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 strain as template and the oligonucleotide pair acn-Prom-5-for/acn-Prom-3-rev for unlabeled DNA and Cy3-acn-Prom-5-for/Cy3-acn-Prom-3-rev (343 bp) for Cy3-labeled DNA. The promoter region of cg1848, which served as nonspecific DNA for the competition experiment, was amplified using the oligonucleotide pair NCgl1580-for/NCgl1580-rev and chromosomal DNA of the ATCC 13032 strain as template. For the EMSAs with MtAcnR, the M. tuberculosis aconitase promoter region was amplified using the oligonucleotides Mt_Acn_Prom_fw and Mt_Acn_Prom_rv and chromosomal DNA of M. tuberculosis strain H37rv as template. In a second PCR using the oligonucleotides Cy3-acn-Prom-5-for and Mt_Acn_Prom_rv and the product from the first PCR as template, the DNA was labeled with Cy3 for detection.

The products were purified with a PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and eluted in EB buffer. Purified AcnR protein was incubated with the DNA fragment in a total volume of 20 μl. 9 ng of the Cy3-labeled DNA fragment corresponding to a final concentration of 2 nm was used for the EMSAs. Unless otherwise stated, the binding buffer contained 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol, and 0.005% Triton X-100. The reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 20 min and then loaded onto 10% native polyacrylamide gels.

When putative effectors were tested, AcnR was first incubated with the compound for 20 min at room temperature, followed by the addition of the DNA and a further 20-min incubation. Before loading onto the gel, 4 μl of loading buffer (0.01% (w/v) xylene cyanol blue, 0.01% (w/v) bromphenol blue, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 10% (v/v) 10× TBE (890 mm Tris base, 890 mm boric acid, 20 mm EDTA)) was added to each sample. Electrophoresis was performed on ice at 180 V for 1.5 h using 1× TBE. The EMSAs with citrate-Mg2+ were performed with loading and running buffer lacking EDTA.

The gels were subsequently scanned using a Typhoon TrioTM scanner (GE Healthcare). For determination of the apparent KD values, the fluorescence intensity of the bands corresponding to unbound and protein-bound DNA was quantified using ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare), followed by calculation of the percentage of bound DNA. These values were plotted against the AcnR concentration in log10 scale, and a sigmoidal fit was performed using the Origin 7 software (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA), taking into account the error bars as well as 0 and 100% shifted DNA as asymptotes. The turning point of the curve was defined as the apparent KD value.

Surface Plasmon Resonance

Experiments were conducted using a Biacore T200 (GE Healthcare). Purified AcnR was immobilized through standard amine coupling methods to a CM5 S-series sensor chip with the protein in running buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mm NaCl, 0.001% Tween 20). The final amount of protein on the chip accounted for ∼4900 RU, allowing a theoretical maximum signal of ∼44 RU for citrate alone with a 1:1 binding stoichiometry with AcnR protomers. AcnR was titrated using 2-fold serial dilutions of citrate and citrate-Mg2+, providing 12 data points with 40 mm being the highest concentration. All measurements were conducted at 25 °C. The binding profiles were fit globally to a 1:1 interaction model using the responses at equilibrium. The response data were processed with BIAevaluation software using a reference surface to correct for any bulk refractive index changes and blank injections for double referencing. The titration was repeated three times and showed consistent results.

Growth Experiments with Strains Containing Mutational Variants of AcnR

C. glutamicum ΔacnR was transformed with pEKEx2 plasmids encoding the native protein or one of the mutational variants under the control of the Ptac (48). This promoter is leaky and leads to a low level expression of the desired protein in C. glutamicum without induction by isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. 5 ml of brain-heart infusion broth (Difco) was inoculated with a colony from a fresh brain-heart infusion broth agar plate and incubated over 1 day at 30 °C and 170 rpm. Cells of this preculture were washed once in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 4.3 mm Na2HPO4, 1.4 mm KH2PO4, pH 7.3) and used to inoculate the second preculture, consisting of 20 ml of CGXII minimal medium (49) supplemented with 3,4-dihydroxybenzoate (30 mg liter−1) as iron chelator and glucose (111 mm) as carbon source. Cells from the second preculture were used to inoculate the main cultures to an A600 of 1 in 48-well FlowerPlates®, which were subsequently incubated at 30 °C, 95% humidity, and 1200 rpm in a BioLector® (m2p-labs, Baesweiler, Germany). The wells contained 750 μl of CGXII minimal medium with either glucose (111 mm) or citrate (50 mm sodium citrate plus 5 mm CaCl2) as carbon source (50). Growth of the BioLector® cultures was monitored by measuring the back-scatter at 620 nm with gains of 10, 15, and 20, respectively. All growth media were supplemented with 25 mg liter−1 kanamycin.

RESULTS

Affinity and Specificity of the AcnR-Operator Interaction

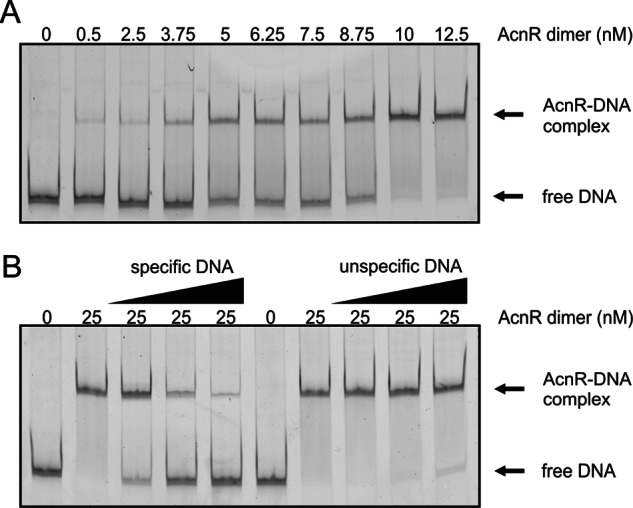

EMSA experiments with AcnR and Cy3-labeled operator DNA (Fig. 1A) gave an apparent KD of 7.7 ± 0.9 nm for the binding of dimeric AcnR to its operator by plotting the percentage of shifted DNA versus the AcnR concentration from five independent experiments. Binding of AcnR to Cy3-labeled operator DNA was inhibited by the addition of unlabeled operator DNA but not by the addition of a control DNA (468-bp fragment covering the promoter region of cg1848) (Fig. 1B). These results confirm the specificity of the AcnR-operator interaction.

FIGURE 1.

Analysis of AcnR-DNA interaction by EMSAs. A, determination of the apparent KD for the binding of AcnR to its operator in the acn promoter. A 2 nm concentration of a Cy3-labeled DNA fragment covering the promoter region of acn was incubated with increasing concentrations of AcnR and analyzed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” An apparent KD of 7.7 ± 0.9 nm was determined for dimeric AcnR. B, competition experiment with specific and nonspecific DNA (unlabeled), 2 nm Cy3-labeled DNA of the acn promoter, and 25 nm AcnR dimer. Specific DNA was unlabeled acn promoter DNA (10 nm, 40 nm, 100 nm), and nonspecific DNA was a 468-bp fragment covering the promoter region of cg1848 (10, 40, and 100 nm).

Initial Search for the Effector of AcnR

Citrate was considered as a prime candidate but showed no effect or only a very weak effect on DNA binding even when added to the gel and the running buffer (data not shown). An extensive set of metabolites and cofactors was subsequently tested, including cis-aconitate, isocitrate, 2-methylcitrate, 2-methyl-cis-aconitate, acetate, acetyl-CoA, fumarate, oxaloacetate, propionate, succinyl-CoA, glucose 6-phosphate, l-glutamate, l-glutamine, a combination of all 20 amino acids, ADP, AMP, ATP, NAD+, NADH, NADP+, or NADPH. However, none had an inhibitory effect on DNA binding under the chosen conditions.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

To identify residues involved in binding to DNA and to potential ligands, AcnR derivatives with single amino acid substitutions were constructed. For the first set (K43A, K55A, and K104A), gel filtration profiles showed that all three still formed dimers but that the ratio of aggregated to dimeric protein was significantly higher for K55A and K104A. EMSAs revealed that the DNA binding affinity was slightly reduced for K104A and almost completely abolished for K43A and K55A. A second set of variants with amino acid substitutions was created based on the structure and will be described below.

Structure of AcnR

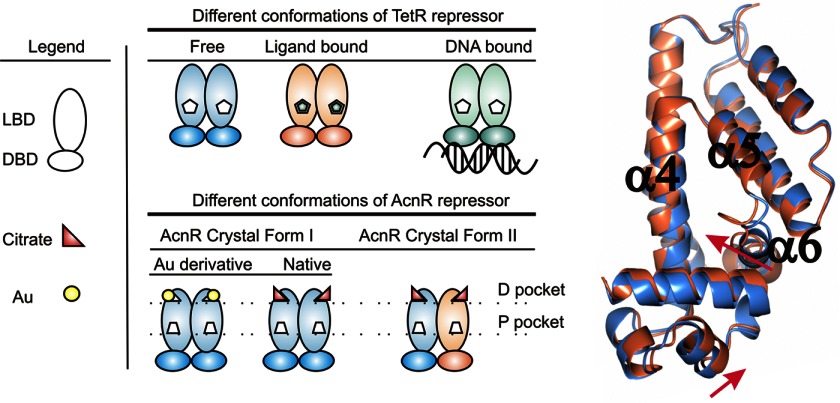

We report the structure in two crystal forms, Form I with one subunit and Form II with a dimer in the asymmetric unit. The overall fold is similar in both forms.

Crystal Form I

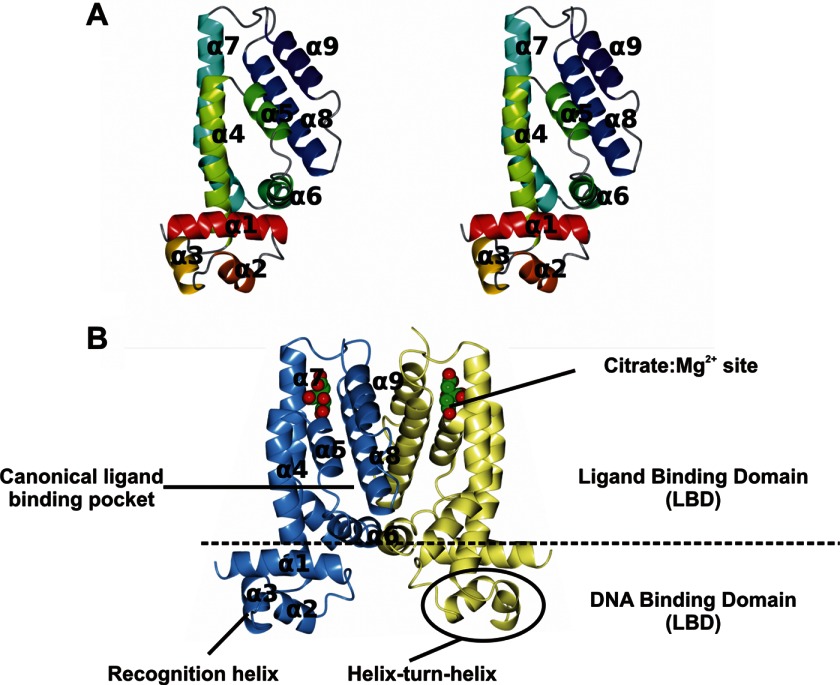

The structures of the native protein and of the heavy atom derivative were solved in this form. The structure shows a typical dimeric TetR-type repressor, where each protomer is all-α with nine α-helices, arranged as a C-terminal dimerization LBD and an N-terminal DBD (Fig. 2) (reviewed in Ref. 22). The DBD is a three-helix bundle formed by α1, α2, and α3 stabilized by hydrophobic helix-to-helix contacts. Residues 1–11 (or 13 in the native protein) preceding α1 are disordered. α2 and α3 form the helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif responsible for DNA binding, α3 being the “recognition” helix responsible for the sequence-specific binding (21). Conserved TetR family residues in this motif form the hydrophobic core or are involved in DNA binding. The recognition helix is strictly conserved in the AcnR subfamily (Fig. 3), and it has a high positive electrostatic potential that contributes to DNA binding (Fig. 4A). It has been suggested that the N terminus of α4 could form part of the DBD because it moves together with it as a rigid unit in molecular dynamics simulations (51). α4 also contains residues such as the conserved Lys-55 (AcnR numbering), which has been demonstrated to contribute a substantial part of the DNA binding energy in TetR (22). Because AcnR binds DNA at an inverted repeat, the distance between the two HTH motifs in the dimer should be ∼34 Å when bound to two adjacent major grooves of DNA. The center-to-center distance in crystal Form I between the Cα of Phe-52 (at the center of the recognition helix) is somewhat longer, ∼42 Å, but TetR-type regulators undergo significant conformational changes upon binding DNA, in addition to the significant changes between free and ligand-bound forms. Indeed, the distance is 40 Å in apo-TetR (52). The interactions between the DBD and LBD involve the C-terminal part of α1 with α4 and α6 of the LBD and are conserved across the TetR family.

FIGURE 2.

The AcnR fold. A, stereo view of the AcnR protomer color-ramped from red to dark blue. B, the AcnR dimer in Form I generated by the crystallographic 2-fold symmetry axis, colored by chain. In B, the citrate-Mg2+ is shown with a space-filling representation. Figs. 2–5 were created using CCP4mg (62).

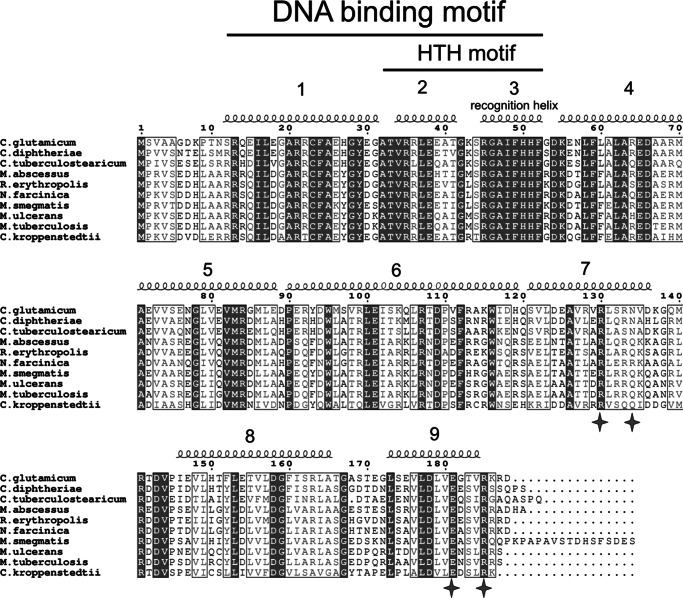

FIGURE 3.

Sequence alignment of AcnR homologues. The conserved residues are highlighted in dark gray, whereas residues with similar physico-chemical properties are boxed in white. The residues hydrogen-bonding the citrate and magnesium ion are highlighted with a star.

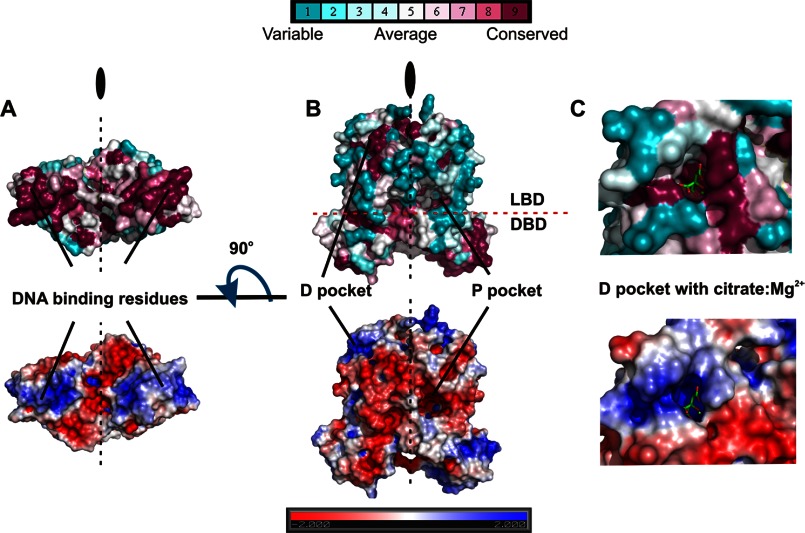

FIGURE 4.

Electrostatic potential and residue conservation in the AcnR DNA binding region (A) and pockets (B and C). The protein is displayed as a surface colored by residue conservation (top) and electrostatic potential (bottom). Residue conservation ranges from fully conserved in purple to not conserved (cyan). Citrate (green carbons) is shown as cylinders in C.

The LBD is responsible for dimerization and ligand binding and is formed by α4–α9. Although its sequence is poorly conserved (Figs. 3 and 4B), it has a common structural core in all TetR-type regulators (22), involving a core triangle formed by three helices (α5, α6, and α7) around which the other elements fold. This triangle is conserved in AcnR, with α7 being significantly bent at Ser-121. α4 runs parallel to α7 at the front of the triangle contacting the DBD, whereas α8 runs parallel to α5 at the back of the triangle, and α9 runs antiparallel to α8. The dimerization interface is formed by a four-helix bundle made up of α8 and α9 positioned orthogonally to their counterparts in the other subunit, which buries a surface area of 1572 Å2 calculated with PISA (53).

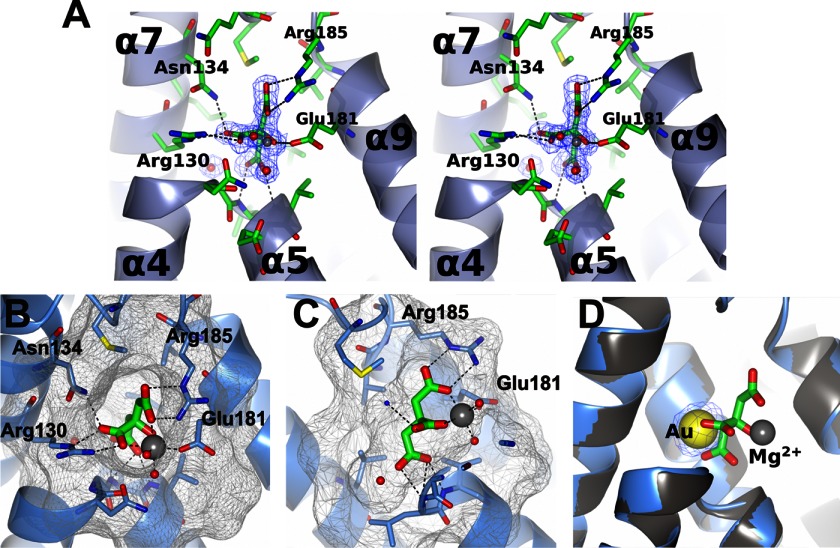

The Distal Pocket, a Citrate-Mg2+ Binding Site in an Unexpected Location

The structure revealed the presence of a citrate-Mg2+ moiety in both subunits of both crystal forms at a site not seen in previous TetR-type repressors (Fig. 5). Based on its distance to the DBD, this will be termed the distal (D) pocket in contrast to the expected canonical TetR site, termed the proximal (P) pocket. The small D pocket is formed by the loop between α4 and α5 and helices α7, α8, and α9 and has a volume of ∼450 Å3. The ligand is positioned with its apolar carbon atoms pointing to the hydrophobic interior and the polar atoms facing the outer side of the pocket. The back of the pocket is formed by hydrophobic residues, including Leu-153, Leu-131, Leu-149, Val-184, and Met-140. The outer part is formed by polar residues (Asn-134, Arg-130, Glu-181, and Arg-185), which bind to the magnesium ion and the polar carboxyl groups of the citrate. The citrate oxygens form hydrogen bonds to the main chain amide groups from residues Leu-79 and Val-80 and to a water molecule. The magnesium ion is octahedrally coordinated by three oxygens of the citrate, two water molecules, and the Glu-181 carboxyl oxygens (Fig. 5, A–C). All residues in the D pocket involved in contacts with the citrate-Mg2+ are conserved in other Corynebacteriales family members, including M. tuberculosis and C. diphtheriae (Figs. 3 and 4). This, together with the high specificity of the interactions and the fact that citrate is the substrate of aconitase, strongly suggests that the complex has biological relevance. Furthermore, the cavity has a high positive electrostatic potential, well suited to accommodate a molecule with negative charges, such as citrate (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 5.

The citrate binding distal pocket. A, stereo view with the citrate and residues contacting the citrate or magnesium depicted as cylinders. The 2Fo − Fc map contoured at the 1σ level is shown for the citrate-Mg2+. B and C, two views of the citrate-Mg2+ bound in the pocket of AcnR with the protein surface displayed to emphasize the shape of the pocket. D, superposition of the heavy atom derivative and native Form I structures. The 2Fo − Fc map at 1σ is shown for the gold ion. The gold in the derivative crystal displaces the citrate-Mg2+.

In the derivative structure, four gold ions bind to each protomer. One displaces the citrate-Mg2+ bound in the native structures (Fig. 5D). This displacement by the gold cyanide suggested only a moderate binding constant for the citrate-Mg2+. The second gold is positioned in the DBD and the two others in the LBD.

Crystal Form II

There is a dimer in the asymmetric unit, made up of subunits A and B. Subunit A is very similar to the protomer seen in Form I, and superposition using SSM (54) showed an r.m.s. deviation over 177 equivalent Cα atoms of ∼0.4 Å. In contrast, subunit B shows significant local differences with an overall r.m.s. deviation of equivalent Cα positions of ∼1 Å from chain A or from Form I. The major differences are in the loop between α5 and α6 in the LBD and the relative position of the DBD with respect to the LBD (Fig. 6). The DBDs of both subunits superpose with an r.m.s. deviation of 0.5 Å, but the position relative to the LBD has changed by ∼2 Å. The electron density for α3 in this subunit is weak, with the side chains of the aromatic residues being poorly defined. This could be due to disorder in the crystal but more likely reflects flexibility between the domains. The distance between the Cα of Phe-52 in the two subunits in this form is 42.6 Å, similar to that in Form I. The structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with codes 4AF5 (Form I), 4AC6 (Form I Au derivative), and 4ACI (Form II).

FIGURE 6.

Different states of the AcnR repressor. Left, scheme of the different functional forms found in TetR repressor and those found in this work for AcnR. Right, comparison of the two independent AcnR protomers in the asymmetric unit (blue and coral) in crystal Form II. The two protomers are superposed, and the movements of α6 and the DBD relative to the LBD are evident.

A Possible Canonical P Pocket

There is a cavity in each subunit roughly corresponding to the canonical tetracycline binding site in TetR. In all of the AcnR subunits in native Forms I and II, this P pocket is empty. Although the P pocket is located at roughly the same place between the three core helices in the various TetR-type repressors for which structural data are available, the exact position of the ligands and size and shape of the pockets varies, reflecting the lack of sequence and hence local structure conservation. In Form I, the P pocket is large, with a volume of 1200 Å3 calculated with CASTp (55). The entrance is on the opposite side to that of the D pocket and is formed by α6–α8 and the loop between α8′ and α9′ from the other subunit. Residues in the entrance are mainly hydrophilic, whereas the inner part of the pocket is lined with hydrophobic residues. Electrostatic calculations with the PBEQ-solver server (56), which uses the CHARMM force field, shows that the cavity has a slightly negative charge (Fig. 4B). Sequence alignments indicate that although Asp-66 and Trp-116 in site D are conserved (Fig. 3), the rest of the pocket lacks conserved residues.

In the LBD of Form 2, one protomer has part of α6 unwound and shifted toward the center of the canonical P pocket by 3 Å, closing it. This change in volume of the P pocket would be in keeping with the binding of a hypothetical ligand. The presence of two distinct binding sites per subunit would represent a new feature not seen before in TetR-type regulators and would imply a complex regulatory mechanism, but we should emphasize that we presently only have experimental evidence for the binding of citrate-Mg2+ and not of a second ligand.

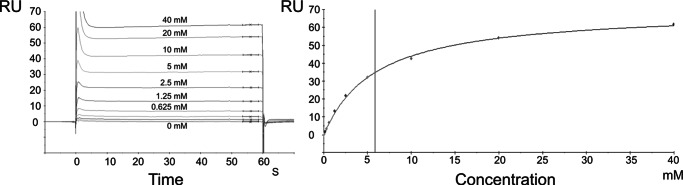

Binding Affinity of Citrate-Mg2+

Having observed the presence of citrate-Mg2+ in the D pocket with highly specific complementary interactions with conserved residues, we proceeded to measure the affinity constant using surface plasmon resonance. Maximum theoretical signals of ∼44 and ∼50 RU for citrate and citrate-Mg2+ were expected, respectively, for a 1:1 stoichiometry with an AcnR protomer. The results indicated clear binding of citrate-Mg2+ to AcnR in a 1:1 ratio with a signal of ∼60 RU, whereas citrate alone did not show any measurable binding (even at 40 mm). A 1:1 Langmuir model gave a good fit based on the sum of the square residuals (χ2), indicating a KD of 6 mm (Fig. 7), within the range of biological significance. For E. coli, an intracellular citrate concentration of 2 mm has been reported (57), and higher concentrations are likely when, for example, aconitase activity is limiting. We conclude that citrate-Mg2+ is likely to contribute to AcnR regulation in vivo.

FIGURE 7.

Surface plasmon resonance titration of citrate-Mg2+ over AcnR. Left, sensorgram showing responses at the different ligand concentrations. Right, 1:1 ratio Langmuir curve fitted to the resulting responses.

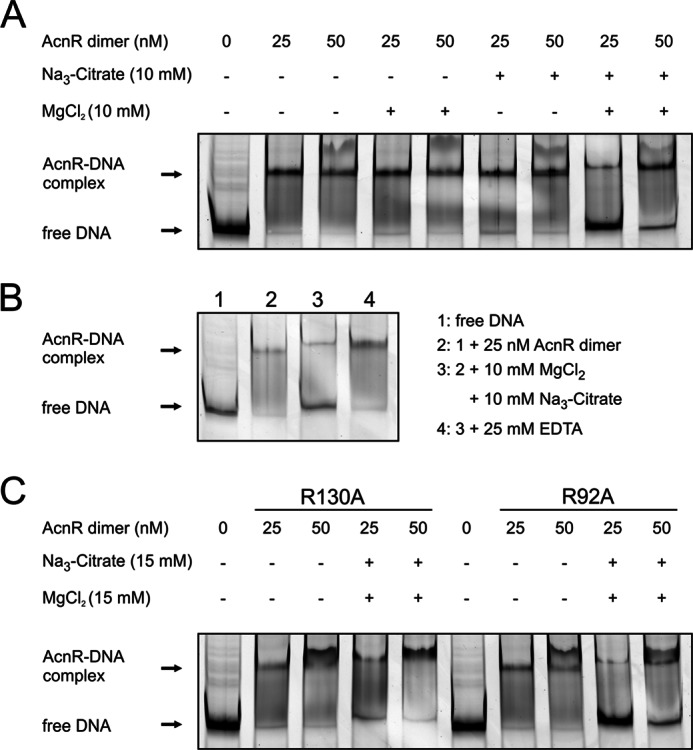

EMSA Studies with Citrate-Mg2+

Because surface plasmon resonance measurements showed Mg2+ to be strictly required for binding of citrate, the EMSA studies were repeated using buffers lacking EDTA and revealed that the affinity of AcnR for DNA is reduced when both Mg2+ and citrate are present (Fig. 8A). Fig. 8B shows the reversibility of the citrate-Mg2+ effect upon DNA binding for removal of Mg2+ with EDTA. In addition, citrate-Ca2+ was tested but did not change the DNA binding affinity of AcnR (results not shown).

FIGURE 8.

Bandshifts showing the effect of citrate-Mg2+ on AcnR-DNA binding. A, influence of Mg2+ and citrate on AcnR-DNA binding, separately and in combination. A 2 nm concentration of a Cy3-labeled DNA fragment covering the promoter region of acn was incubated with AcnR, Mg2+, and/or citrate as indicated. Only if both citrate and Mg2+ are added can a backshift be observed. B, reversibility of the citrate-Mg2+ effect. AcnR was incubated with DNA in binding buffer. A sample was taken (2), and the remaining complex was supplemented with Mg2+ and citrate. After a further 5 min, another sample was taken (3). EDTA was added, and another sample was taken after 5 min (4). C, influence of citrate-Mg2+ on mutational variants of AcnR. Arg-130 is involved in citrate binding, and the R130A variant no longer reacts to citrate-Mg2+. The same amino acid exchange at another position (Arg-92 within the P pocket) does not change the behavior of AcnR in the presence of citrate-Mg2+.

The Mutated AcnR Variants

A number of conserved charged residues were mutated to alanine to probe their functional relevance. Several of these exchanges were made in advance of the three-dimensional structure, but their properties can now be assessed in structural terms. A summary of these results is given in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Properties of AcnR derivatives used

| Mutation | Location | Further information |

|---|---|---|

| pEKEx2-AcnR-STREP derivatives | ||

| K43A | DBD | Almost complete abolishment of DNA binding |

| K55A | DBD | Complete abolishment of DNA binding |

| K104A | Dimer interface | DNA affinity close to wild-type protein |

| E65A | Beginning of α4 | Maybe involved in signal transduction to the DNA binding domain, no effect on DNA binding |

| D66A | Beginning of α4 | Maybe involved in signal transduction to the DNA binding domain, no effect on DNA binding |

| R99A | P pocket | Weaker binding to DNA |

| D109A | Protein surface | No effect on DNA binding |

| R130A | D pocket | Hydrogen-bonds to citrate, does not change its affinity to DNA in the presence of citrate-Mg2+ |

| R141A | Protein surface | No effect on DNA binding |

| D143A | Protein surface | No effect on DNA binding |

| D158A | P pocket | Weaker binding to DNA |

| E181A | D pocket | Binds Mg ion, does not change its affinity to DNA in the presence of citrate-Mg2+ |

| R185A | D pocket | Hydrogen-bonds to citrate, does not change its affinity to DNA in the presence of citrate-Mg2+ |

| pET-TEV-AcnR derivatives | ||

| C23A | Within α1 | No obvious difference in behavior, |

| R69A | P pocket | No obvious difference in behavior |

| M70A | P pocket | No obvious difference in behavior |

| M86A | P pocket | No obvious difference in behavior |

| R92A | P pocket | No obvious difference in behavior |

| W95A | P pocket | No obvious difference in behavior |

| R130A | D pocket | Does not change its affinity to DNA in the presence of citrate-Mg2+ |

Mutations in the DNA-binding Region

Mutein K55A shows no binding to the acn promoter even at concentrations up to 770 nm, indicating either a crucial role for DNA binding or defects in folding. It is located at the beginning of α4, is equivalent to Lys-48 in TetR, and is the most conserved residue in the TetR family, forming conserved hydrogen bonds with the carbonyl oxygen atoms at positions 22 and 25 (positions 29 and 32 in AcnR). In addition, it is proposed to form a salt bridge with the DNA phosphate backbone. Lys-43 is not conserved, but it is located between α2 and α3 at the dimer interface and might be involved in the recognition of the specific binding sequence. Its mutation has only a minor effect on DNA binding, but it might be involved in signal transduction because it connects α6 in the LBD from one subunit with α1 in the DBD from the other subunit.

Mutations in the D Pocket

To confirm the specificity of the interaction between AcnR and citrate-Mg2+, we introduced mutations in residues involved in binding of either citrate or Mg2+. For muteins R130A, E181A, and R185A, the inhibition of DNA binding by citrate-Mg2+ is no longer observed (Fig. 8C; data for E181A and R185A not shown). As controls, we used variants with mutations in other domains (R95A and C26A), which behaved like the wild-type protein.

Mutations in the P Pocket

The D109A, R141A D143A, E65A, and D66A mutations had no effect on DNA binding, but an effect might be anticipated if experiments were done in the presence of a yet to be identified P ligand alone or in combination with citrate-Mg2+. The mutations R99A and D158A are located in α6 and α8, respectively, and resulted in a lower affinity for DNA. Their side chains extend into the P pocket and might be involved in ligand binding.

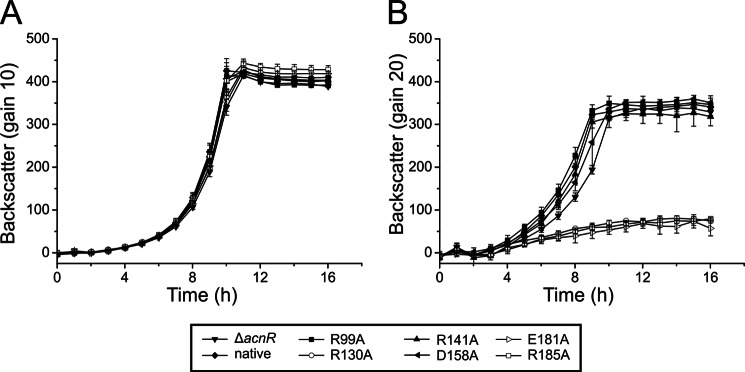

Effect of AcnR Variants under Physiological Conditions

To test for an in vivo effect of the AcnR variants that are defective in citrate binding (R130A, E181A, and R185A), C. glutamicum ΔacnR was transformed with plasmid-encoded AcnR variants and cultivated in CGXII minimal medium with either glucose or citrate as carbon source (Fig. 9). On glucose, no significant growth differences between the strains were observed. In contrast, on citrate, the three strains with citrate binding-defective AcnR were no longer able to grow. All other tested AcnR variants with amino acid exchanges not affecting citrate-Mg2+ binding (R99A, R141A, and D158A) and wild-type AcnR did not influence growth on citrate.

FIGURE 9.

Growth of C. glutamicum ΔacnR harboring different AcnR variants on glucose (A) and citrate (B). After precultivation in brain-heart infusion broth and CGXII glucose medium, cells of C. glutamicum ΔacnR carrying pEKEx2 plasmids encoding the native or a mutational variant of AcnR were cultivated in CGXII minimal medium containing either 111 mm glucose (A) or 50 mm sodium citrate and 5 mm CaCl2 (B) at 30 °C and 1200 rpm in a Biolector® system. Averages and S.D. values (error bars) of three biological replicates are shown.

Purification and Analysis of M. tuberculosis AcnR

The AcnR homologues of C. glutamicum and M. tuberculosis (Rv1474c) share a sequence identity of 53% and a similarity of 69%. Nonetheless, the MtAcnR protein showed very different properties during purification and analysis. It was not possible to overproduce MtAcnR in a soluble form in E. coli using the pET-TEV-MtAcnR plasmid. Several purification attempts under denaturing conditions followed by refolding also failed. By fusing MtAcnR to the E. coli maltose-binding protein (MBP) lacking its signal peptide, it was possible to obtain soluble protein that could be purified by amylose affinity chromatography. The resulting fusion protein was used for EMSAs with a DNA fragment covering the promoter region of the M. tuberculosis aconitase gene. The band of the unbound DNA disappeared upon incubation with MBP-MtAcnR, but no distinct band of the protein-DNA complex was observed. Therefore, the MBP part of the fusion protein was cleaved off by TEV protease, which led to immediate aggregation of most of the cleaved MtAcnR. The aggregates were removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant, which contained small amounts of soluble MtAcnR in addition to uncleaved fusion protein and MBP, was used for EMSAs. This resulted in a distinct band representing the MtAcnR-DNA complex (data not shown), confirming that MtAcnR, like CgAcnR, binds to the promoter region of the M. tuberculosis aconitase gene.

DISCUSSION

The AcnR Fold

The structure is typical of the TetR family of transcriptional regulators with a homodimer in an Ω-shape with a DBD and a LBD. A search in SCOP (58) with the AcnR coordinates showed as main hits two known repressors belonging to the TetR family, the QacR protein (Protein Data Bank code 1JTO) and the γ-butyrolactone receptor (Protein Data Bank code 1UI5).

Binding Properties of AcnR and Effector Search

The apparent KD for binding of AcnR to its operator in the acn promoter region was determined to be 7.7 nm, in the range expected for this type of repressor, and the specificity of binding was confirmed. In the search for ligands that prevent DNA binding of AcnR, citrate was always considered as a favorite candidate, because it is the substrate of aconitase and its accumulation in the cell would indicate insufficient aconitase activity. We recently showed that deletion of the acn gene in C. glutamicum strongly favors secondary mutations in the gltA gene encoding citrate synthase that lead to enzyme inactivation or degradation (12). Because aconitase is the only enzyme in C. glutamicum known to metabolize citrate, citrate accumulation can be assumed to have toxic effects (e.g. by chelating divalent metal ions, such as Mg2+ or Fe2+, or by allosteric inhibition of key metabolic enzymes). The gltA mutations prevent citrate formation and thus its potentially toxic effects. Citrate was strictly required for crystallization of AcnR and was bound to the D pocket in both crystal forms. Only after modifying the EMSA conditions to exclude EDTA could an inhibitory effect of citrate-Mg2+ on AcnR-DNA binding be shown.

In Vivo Effect of AcnR Mutations

During analysis of the in vivo effect of the AcnR variants that no longer reacted to citrate-Mg2+ in EMSA studies (R130A, E181A, and R185A), it was found that C. glutamicum ΔacnR strains carrying these variants are unable to grow on citrate, whereas growth on glucose was not affected. Only after more than 40 h was growth observed in the respective wells, most likely due to suppressor mutations. Aconitase is the only known enzyme of C. glutamicum that is able to metabolize citrate and therefore is strictly required for growth on this substrate, which can be imported by two different transport systems (50, 59). Aconitase transcription is repressed by AcnR, which is itself inhibited by the binding of citrate-Mg2+. This derepression is impeded with the AcnR variants described above, which seems to completely block citrate metabolism. Aconitase deletion mutants are not able to grow in CGXII glucose medium without the addition of glutamate or glutamine (12). Because the strains carrying the citrate binding-defective AcnR variants were still able to grow in glucose medium, aconitase transcription cannot be entirely blocked. Several reasons can be envisaged for the differences in the growth behavior on glucose and citrate of the mutant strains carrying AcnR-R130A, -E181A, or -R185A. (i) During growth on glucose, but not on citrate, the postulated second effector molecule of AcnR is formed in a concentration sufficient to cause derepression of acn, although citrate cannot bind to AcnR anymore. This option requires that binding of this effector molecule to AcnR or its derivatives is sufficient to inhibit the interaction with the operator. It is also possible that the mutations in AcnR lead to conformational changes in such a way that the second effector molecule alone is able to inhibit AcnR-DNA complex formation. (ii) The carbon flux through aconitase is lower on glucose than on citrate, and the residual aconitase expression in the presence of the citrate binding-defective AcnR proteins is sufficient to allow this flux. On citrate, the aconitase activity is insufficient; citrate accumulates within the cells and inhibits growth, as discussed in our previous work (12). (iii) The repression by the mutated AcnR derivatives could also inhibit acn expression by preventing positive regulation of acn by other regulators, such as RamA (15). It was shown before that in a ΔacnR mutant, the aconitase activity is 1.7-fold higher on citrate than on glucose, in line with a transcriptional activation of acn during growth on citrate (8).

The D Pocket

This small pocket is positioned further away from the DBD than the canonical P pocket. It is occupied in both native structures by a citrate-Mg2+ moiety, which forms very specific contacts with high shape and electrostatic complementarity, including six protein-citrate hydrogen bonds plus one protein-magnesium bond, with residues contacting the ligand being highly conserved. Subsequently, an inhibitory effect of citrate-Mg2+ on DNA binding was shown in EMSA studies but only in the absence of EDTA (Fig. 8B). Furthermore, the affinity of citrate-Mg2+ for AcnR is in a range that is likely to be physiologically significant, because the lack of converting enzyme leads to an increase of citrate. This strongly suggests that citrate-Mg2+ plays a biological role.

The Possibility of Two Ligand Binding Pockets per Protomer

We have shown that citrate-Mg2+ binding to the D pocket has a functional effect. This is a new site, not seen in previous TetR family receptors. However, under the conditions used, even 10 mm citrate-Mg2+ does not completely prevent DNA binding, and the inhibition could be overcome by using more AcnR protein (Fig. 8).

There is a second larger pocket in AcnR close to the canonical TetR ligand binding site, but we see no ligand at this site, and the only conserved residues in the AcnR subfamily in this pocket are Asp-158 and Trp-116. Nevertheless, the structural changes observed in the two protomers in crystal Form II resemble those occurring in the TetR repressor upon ligand binding, which may suggest that there is a second effector molecule that binds to the P site. One possibility would be a second ligand that influences the DNA-binding ability independently of citrate-Mg2+. However, although we tested a large set of possible ligands, none inhibited DNA binding. Alternatively, there might be cross-talk between the P and the D pockets, with the putative second ligand and citrate-Mg2+ showing negative or positive cooperativity. Such behavior would add an additional level of complexity to the regulation of AcnR and be in line with an exceptionally tight regulation of aconitase synthesis, because it is presumed to be the only enzyme of C. glutamicum capable of metabolizing citrate (12); is oxygen-sensitive due to its iron-sulfur cluster (10); and is part of three important metabolic pathways, the TCA cycle, the methylcitrate cycle, and the glyoxylate shunt.

The D Pocket Is Unique to AcnR

Superposition of the AcnR DBD on those of other TetR members shows a highly conserved structure. However, the LBD shows a much lower similarity apart from the three core helices. Nevertheless, there is a resemblance in the general fold regarding the orientation and packing of the helices against one another. A clear difference between AcnR and other members is the shortening of helices 4 and 5, which appears to result in the creation of the entrance to the independent D pocket. This feature cannot only be seen in the structure but is also evident in sequence alignments where there is a deletion of seven residues compared with TetR and of up to 10 residues compared with AcrR. This deletion also occurs in other AcnRs belonging to non-C. glutamicum species, such as C. diphtheriae, suggesting that the pocket is present throughout the AcnR family.

One exception to this is the structure of EthR in complex with hexanoic acid (60) (Protein Data Bank code 1U9O), where the ligand occupies the canonical proximal site, binding between the three core helices, but stretches beyond the P pocket up between helices 4, 5, 7, and 9 to also fill a space essentially equivalent to that of the citrate-Mg2+ pocket in AcnR. Thus, in EthR, although the position equivalent to the AcnR citrate-Mg2+ pocket is also involved in ligand binding, here it simply forms an extension of the larger P pocket. Furthermore, in EthR, helices 4 and 5 extend as far as 7 and 9 and block direct access to this pocket, leaving it to be accessed exclusively through the P pocket. In summary, most of the structures do not contain a D pocket due to the extension of helices 4 and 5, with the exception of EthR, where it acts as an extension of the canonical P pocket to accommodate the hexanoic acid.

DNA Binding and Allosteric Mechanism

The binding of TetR to DNA is proposed to depend on its inherent flexibility, whereas upon ligand binding, TetR becomes rigid and can no longer bind DNA. The first evidence in support of this was that the ligand-free structure had a longer distance between the DBD than that needed to bind two consecutive major grooves on the DNA; this distance was even bigger than in the tetracycline-bound crystal form. A mechanism was proposed where, upon binding of tetracycline-Mg2+ in the canonical pocket, helix α6 unwinds and is displaced to the inside of the pocket, α4 then acts as a pivotal point to transmit the information to the DBDs, and TetR is released from DNA. Lys-48 (Lys-55 in AcnR and conserved among all TetR members) on α4 has been proposed to account for most of the energy of interaction with DNA. It has been supposed that other members of the family have similar mechanisms, excepting CmeR, where the affinity for DNA is lost not because of rigidification but due to disordering of the recognition helix (61).

In AcnR, the center-to-center HTH distance is about 42 Å for both crystal forms, similar to that in unliganded TetR. The differences between the two subunits in crystal Form II resemble the structural changes that occur in TetR upon binding of tetracycline-Mg2+. Helix α6 of protomer B in AcnR Form II unwinds and is displaced toward the center of the cavity. It is likely that this conformational change between the two AcnR protomers reveals biologically relevant changes upon ligand binding, similar to that in TetR, upon binding of the putative second ligand. However, the mechanism of transmission of the signal from the citrate-binding pocket to the DBD is not clear from the crystal structures because both crystal forms contain citrate-Mg2+ in the D pocket. This provides further support for a putative second ligand, yet to be identified, binding to the P site.

Role of AcnR in Other Members of Corynebacteriales

The AcnR protein sequence and the location of its gene downstream of an aconitase gene are highly conserved within bacteria of the order Corynebacteriales; for example, the AcnR homologue of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Rv1474c) shares a sequence identity of 53%. We purified the AcnR protein from M. tuberculosis and demonstrated that it binds to the promoter region of the acn gene (Rv1475c) of this pathogenic species. This supports the view that the AcnR homologues have a similar function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the Diamond Light Source (beamline I02) and ESRF (beamlines ID14-1 and ID29) for provision of synchrotron facilities and Sam Hart for assistance in data collection. In addition, we thank Christina Mack for performing several of the EMSA experiments.

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 4AF5, 4AC6, and 4AF5) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- TCA

- tricarboxylic acid

- DBD

- DNA-binding domain

- LBD

- dimerization and ligand-binding domain

- TEV

- tobacco etch virus

- D pocket

- distal pocket

- P pocket

- proximal pocket

- r.m.s.

- root mean square

- MBP

- maltose-binding protein

- HTH

- helix-turn-helix

- RU

- resonance units.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kinoshita S., Udaka S., Shimono M. (1957) Studies of amino acid fermentation. I. Production of l-glutamic acid by various microorganisms. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 3, 193–205 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leuchtenberger W., Huthmacher K., Drauz K. (2005) Biotechnological production of amino acids and derivatives. Current status and prospects. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 69, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eggeling L., Bott M. (2005) Handbook of Corynebacterium glutamicum, CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burkovski A. (2008) Corynebacteria: Genomics and Molecular Biology, Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, UK [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yukawa H., Inui M. (2013) Corynebacterium glutamicum: Biology and Biotechnology, Springer Verlag, Heidelberg [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bott M. (2007) Offering surprises. TCA cycle regulation in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Trends Microbiol. 15, 417–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bott M., Eikmanns B. J. (2013) TCA cycle and glyoxylate shunt of Corynebacterium glutamicum. in Corynebacterium glutamicum: Biology and Biotechnology (Yukawa H., Inui M., eds) pp. 281–314, Springer Verlag, Heidelberg [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krug A., Wendisch V. F., Bott M. (2005) Identification of AcnR, a TetR-type repressor of the aconitase gene acn in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 585–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beinert H., Kennedy M. C., Stout C. D. (1996) Aconitase as iron-sulfur protein, enzyme, and iron-regulatory protein. Chem. Rev. 96, 2335–2374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baumgart M., Bott M. (2011) Biochemical characterisation of aconitase from Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Biotechnol. 154, 163–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gruer M. J., Guest J. R. (1994) 2 genetically-distinct and differentially-regulated aconitases (AcnA and AcnB) in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 140, 2531–2541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baumgart M., Mustafi N., Krug A., Bott M. (2011) Deletion of the aconitase gene in Corynebacterium glutamicum causes a strong selection pressure for secondary mutations inactivating citrate synthase. J. Bacteriol. 193, 6864–6873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wendisch V. F., de Graaf A. A., Sahm H., Eikmanns B. J. (2000) Quantitative determination of metabolic fluxes during coutilization of two carbon sources. Comparative analyses with Corynebacterium glutamicum during growth on acetate and/or glucose. J. Bacteriol. 182, 3088–3096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wennerhold J., Krug A., Bott M. (2005) The AraC-type regulator RipA represses aconitase and other iron proteins from Corynebacterium under iron limitation and is itself repressed by DtxR. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 40500–40508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Emer D., Krug A., Eikmanns B. J., Bott M. (2009) Complex expression control of the Corynebacterium glutamicum aconitase gene. Identification of RamA as a third transcriptional regulator besides AcnR and RipA. J. Biotechnol. 140, 92–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Han S. O., Inui M., Yukawa H. (2008) Effect of carbon source availability and growth phase on expression of Corynebacterium glutamicum genes involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle and glyoxylate bypass. Microbiology 154, 3073–3083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Frunzke J., Bott M. (2008) Regulation of iron homeostasis in Corynebacterium glutamicum. in Corynebacteria: Genomics and Molecular Biology (Burkovski A., ed) pp. 241–266, Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, UK [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cramer A., Gerstmeir R., Schaffer S., Bott M., Eikmanns B. J. (2006) Identification of RamA, a novel LuxR-type transcriptional regulator of genes involved in acetate metabolism of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 188, 2554–2567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kohl T. A., Tauch A. (2009) The GlxR regulon of the amino acid producer Corynebacterium glutamicum. Detection of the corynebacterial core regulon and integration into the transcriptional regulatory network model. J. Biotechnol. 143, 239–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Toyoda K., Teramoto H., Inui M., Yukawa H. (2011) Genome-wide identification of in vivo binding sites of GlxR, a cyclic AMP receptor protein-type regulator in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 193, 4123–4133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ramos J. L., Martínez-Bueno M., Molina-Henares A. J., Terán W., Watanabe K., Zhang X., Gallegos M. T., Brennan R., Tobes R. (2005) The TetR family of transcriptional repressors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69, 326–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yu Z., Reichheld S. E., Savchenko A., Parkinson J., Davidson A. R. (2010) A comprehensive analysis of structural and sequence conservation in the TetR family transcriptional regulators. J. Mol. Biol. 400, 847–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Orth P., Saenger W., Hinrichs W. (1999) Tetracycline-chelated Mg2+ ion initiates helix unwinding in Tet repressor induction. Biochemistry 38, 191–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Orth P., Schnappinger D., Hillen W., Saenger W., Hinrichs W. (2000) Structural basis of gene regulation by the tetracycline inducible Tet repressor-operator system. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 215–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schumacher M. A., Miller M. C., Grkovic S., Brown M. H., Skurray R. A., Brennan R. G. (2001) Structural mechanisms of QacR induction and multidrug recognition. Science 294, 2158–2163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schumacher M. A., Miller M. C., Grkovic S., Brown M. H., Skurray R. A., Brennan R. G. (2002) Structural basis for cooperative DNA binding by two dimers of the multidrug-binding protein QacR. EMBO J. 21, 1210–1218; Correction (2002) EMBO J. 21, 2301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Itou H., Okada U., Suzuki H., Yao M., Wachi M., Watanabe N., Tanaka I. (2005) The CGL2612 protein from Corynebacterium glutamicum is a drug resistance-related transcriptional repressor. Structural and functional analysis of a newly identified transcription factor from genomic DNA analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 38711–38719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Itou H., Watanabe N., Yao M., Shirakihara Y., Tanaka I. (2010) Crystal structures of the multidrug binding repressor Corynebacterium glutamicum CgmR in complex with inducers and with an operator. J. Mol. Biol. 403, 174–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Le T. B., Schumacher M. A., Lawson D. M., Brennan R. G., Buttner M. J. (2011) The crystal structure of the TetR family transcriptional repressor SimR bound to DNA and the role of a flexible N-terminal extension in minor groove binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 9433–9447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Le T. B., Stevenson C. E., Fiedler H.-P., Maxwell A., Lawson D. M., Buttner M. J. (2011) Structures of the TetR-like simocyclinone efflux pump repressor, SimR, and the mechanism of ligand-mediated derepression. J. Mol. Biol. 408, 40–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. García-Nafría J., Baumgart M., Bott M., Wilkinson A. J., Wilson K. S. (2010) The Corynebacterium glutamicum aconitase repressor. Scratching around for crystals. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 66, 1074–1077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. (1989) Molecular cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eikmanns B. J., Thum-Schmitz N., Eggeling L., Lüdtke K. U., Sahm H. (1994) Nucleotide-sequence, expression and transcriptional analysis of the Corynebacterium glutamicum gltA gene encoding citrate synthase. Microbiology 140, 1817–1828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hanahan D. (1983) Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166, 557–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schmidt T. G., Skerra A. (2007) The Strep-tag system for one-step purification and high-affinity detection or capturing of proteins. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1528–1535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Niebisch A., Kabus A., Schultz C., Weil B., Bott M. (2006) Corynebacterial protein kinase G controls 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase activity via the phosphorylation status of the OdhI protein. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 12300–12307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leslie A. G. (2006) The integration of macromolecular diffraction data. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 48–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Battye T. G., Kontogiannis L., Johnson O., Powell H. R., Leslie A. G. (2011) iMOSFLM. A new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 271–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Evans P. (2006) Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 72–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Winn M. D., Ballard C. C., Cowtan K. D., Dodson E. J., Emsley P., Evans P. R., Keegan R. M., Krissinel E. B., Leslie A. G., McCoy A., McNicholas S. J., Murshudov G. N., Pannu N. S., Potterton E. A., Powell H. R., Read R. J., Vagin A., Wilson K. S. (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 235–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sheldrick G. M. (2010) Experimental phasing with SHELXC/D/E. Combining chain tracing with density modification. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 479–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cowtan K. (2006) The Buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 1002–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Murshudov G. N., Skubák P., Lebedev A. A., Pannu N. S., Steiner R. A., Nicholls R. A., Winn M. D., Long F., Vagin A. A. (2011) REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 355–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Davis I. W., Murray L. W., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2004) MolProbity. Structure validation and all-atom contact analysis for nucleic acids and their complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W615–W619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. van der Rest M. E., Lange C., Molenaar D. (1999) A heat shock following electroporation induces highly efficient transformation of Corynebacterium glutamicum with xenogeneic plasmid DNA. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 52, 541–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Keilhauer C., Eggeling L., Sahm H. (1993) Isoleucine synthesis in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Molecular analysis of the ilvB-ilvN-ilvC operon. J. Bacteriol. 175, 5595–5603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Brocker M., Schaffer S., Mack C., Bott M. (2009) Citrate utilization by Corynebacterium glutamicum is controlled by the CitAB two-component system through positive regulation of the citrate transport genes citH and tctCBA. J. Bacteriol. 191, 3869–3880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Aleksandrov A., Schuldt L., Hinrichs W., Simonson T. (2008) Tet repressor induction by tetracycline. A molecular dynamics, continuum electrostatics, and crystallographic study. J. Mol. Biol. 378, 898–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Orth P., Cordes F., Schnappinger D., Hillen W., Saenger W., Hinrichs W. (1998) Conformational changes of the Tet repressor induced by tetracycline trapping. J. Mol. Biol. 279, 439–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Krissinel E., Henrick K. (2007) Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Krissinel E., Henrick K. (2004) Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2256–2268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dundas J., Ouyang Z., Tseng J., Binkowski A., Turpaz Y., Liang J. (2006) CASTp. Computed atlas of surface topography of proteins with structural and topographical mapping of functionally annotated residues. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W116–W118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jo S., Vargyas M., Vasko-Szedlar J., Roux B., Im W. (2008) PBEQ-Solver for online visualization of electrostatic potential of biomolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W270–W275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bennett B. D., Kimball E. H., Gao M., Osterhout R., Van Dien S. J., Rabinowitz J. D. (2009) Absolute metabolite concentrations and implied enzyme active site occupancy in Escherichia coli. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 593–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Murzin A. G., Brenner S. E., Hubbard T., Chothia C. (1995) SCOP. A structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J. Mol. Biol. 247, 536–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Polen T., Schluesener D., Poetsch A., Bott M., Wendisch V. F. (2007) Characterization of citrate utilization in Corynebacterium glutamicum by transcriptome and proteome analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 273, 109–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Frénois F., Engohang-Ndong J., Locht C., Baulard A. R., Villeret V. (2004) Structure of EthR in a ligand bound conformation reveals therapeutic perspectives against tuberculosis. Mol. Cell 16, 301–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gu R., Su C. C., Shi F., Li M., McDermott G., Zhang Q., Yu E. W. (2007) Crystal structure of the transcriptional regulator CmeR from Campylobacter jejuni. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 583–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. McNicholas S., Potterton E., Wilson K. S., Noble M. E. (2011) Presenting your structures. The CCP4mg molecular-graphics software. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 386–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.