Abstract

Adult-onset autosomal-dominant leukodystrophy (ADLD) is a progressive and fatal neurological disorder characterized by early autonomic dysfunction, cognitive impairment, pyramidal tract and cerebellar dysfunction, and white matter loss in the central nervous system. ADLD is caused by duplication of the LMNB1 gene, which results in increased lamin B1 transcripts and protein expression. How duplication of LMNB1 leads to myelin defects is unknown. To address this question, we developed a mouse model of ADLD that overexpresses lamin B1. These mice exhibited cognitive impairment and epilepsy, followed by age-dependent motor deficits. Selective overexpression of lamin B1 in oligodendrocytes also resulted in marked motor deficits and myelin defects, suggesting these deficits are cell autonomous. Proteomic and genome-wide transcriptome studies indicated that lamin B1 overexpression is associated with downregulation of proteolipid protein, a highly abundant myelin sheath component that was previously linked to another myelin-related disorder, Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Furthermore, we found that lamin B1 overexpression leads to reduced occupancy of Yin Yang 1 transcription factor at the promoter region of proteolipid protein. These studies identify a mechanism by which lamin B1 overexpression mediates oligodendrocyte cell–autonomous neuropathology in ADLD and implicate lamin B1 as an important regulator of myelin formation and maintenance during aging.

Introduction

Myelin defects are characteristic of both common sporadic neurological diseases such as MS and rare genetic diseases such as adult-onset autosomal-dominant leukodystrophy (ADLD). Investigation of rare inherited diseases whose pathologic features overlap with common syndromes often casts light on critical features of common disorders. Leukodystrophies are a heterogeneous group of rare, usually genetic, disorders characterized by white matter pathologies. ADLD is a progressive and fatal neurological disorder with onset typically in the fourth or fifth decade of life. ADLD is characterized by early autonomic dysfunction and cognitive impairment, followed by pyramidal tract and cerebellar impairments, and loss of white matter in the brain and spinal cord on magnetic resonance imaging. ADLD is often misdiagnosed as chronic progressive MS in its initial phases. ADLD is caused by duplication of the LMNB1 gene, resulting in increased lamin B1 transcripts and protein expression (1). The links between lamin B1 overexpression and demyelination are not understood. Improved understanding of ADLD pathogenesis holds the promise of providing insights into more common sporadic white matter pathologies.

Myelin is a lipid-enriched specialized membrane synthesized by oligodendrocytes in the CNS and Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system (2). Myelin wraps around axons, leading to a substantial increase in axonal conductance. Defects in myelin disrupt axonal function and lead to axonal degeneration, although the precise mechanisms are not known (2). Several proteins, such as myelin basic protein, myelin-associated glycoprotein, and proteolipid protein (PLP), are either restricted to, or highly enriched in, the myelin membrane (3). Mutations of the X-linked PLP1 gene encoding PLP, the most abundant protein of the CNS myelin sheath, cause Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease (PMD), another rare leukodystrophy (4). Mutations in PLP1 ultimately result in the loss or reduction of PLP in the myelin sheath. PMD patients and rodent models of PMD show loss of white matter and axonal degeneration, indicating that the integrity of the myelin-axon unit is highly sensitive to deficits in PLP (5–8).

Lamins are intermediate filament proteins lining the inner nuclear membrane and distributed throughout the nucleoplasm. There are 2 major mammalian lamin types, lamin A and B. A-type lamins are derived from the LMNA gene through alternative splicing, giving rise to 2 isoforms, A and C. B-type lamins, B1 and B2, are encoded by different genes (LMNB1 and LMNB2) (9, 10). The nuclear lamina is implicated in a wide range of human diseases collectively known as laminopathies (11, 12). Numerous functions are ascribed to nuclear lamina, including docking sites for chromatin, regulation of gene expression, and nuclear stability (13, 14). Lamin B1 is known to maintain nuclear integrity and mediate transcriptional regulation (15–17).

We now report a BAC-mediated transgenic approach to generating a BAC transgenic mouse model of ADLD (Lmnb1BAC). This approach allows the advantage of expressing full-length lamin B1 murine homolog (Lmnb1) under the control of endogenous lamin B1 promoter and regulatory sequences. Lmnb1BAC mice recapitulated many of the features of ADLD. In addition, we generated a series of transgenic mice overexpressing Lmnb1 in specific CNS cell lineages. Our findings indicate that overexpression in oligodendrocytes is sufficient for the onset of histopathological, molecular, and behavioral deficits characteristic of ADLD. As in ADLD, pathophysiological effects become evident in adult animals and progressively worsen with age. Using Lmnb1BAC mice as the starting point for transcriptome and proteomic profiling, we discovered that PLP is downregulated in these animals and that the transcriptional occupancy of Yin Yang 1 (YY1), a transcriptional activator of Plp1 (18), is reduced. These results provide a potential link between lamin B1 overexpression and PLP downregulation. Together, our findings reveal a valid in vivo model for investigation of how aging and genetic predispositions can cause myelin defects with devastating effects on health and behavior.

Results

Generation of an ADLD mouse model.

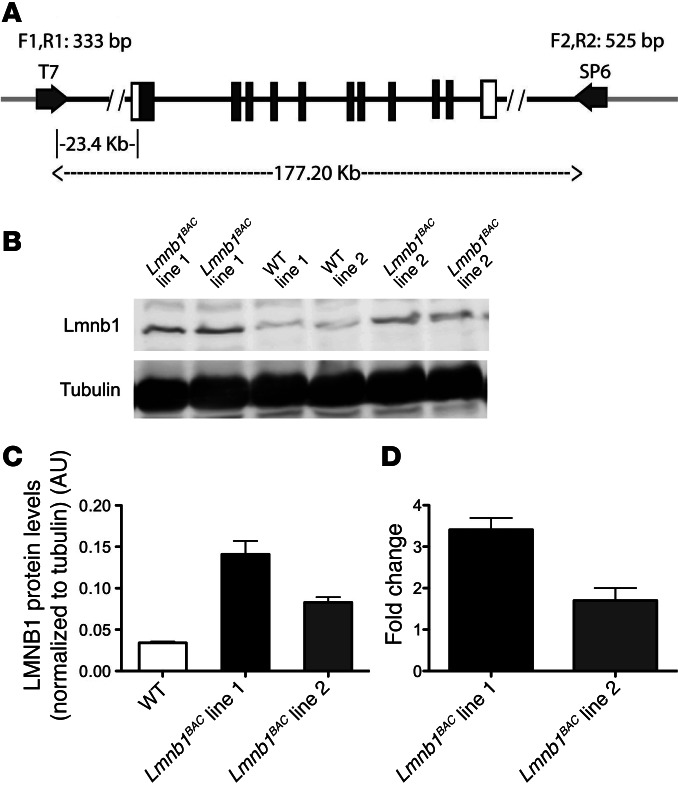

To investigate the pathophysiological mechanism of lamin B1 overexpression in ADLD, we generated BAC transgenic mice carrying additional copies of murine WT lamin B1 (Lmnb1BAC). To maintain the regulatory properties of the endogenous Lmnb1 gene, we made use of large genomic fragments containing the entire Lmnb1 locus within the BAC. A genomic insert containing Lmnb1 (Figure 1A) was isolated from a mouse BAC genomic library. We generated 2 BAC transgenic lines containing varying numbers of the entire Lmnb1 locus. We performed expression analyses of lamin B1 by Western blot and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) from hemibrains of 12-month-old Lmnb1BAC animals. Western blot analysis of Lmnb1BAC transgenic animals showed approximately 4- (line no. 1) and 2.5-fold (line no. 2) higher expression compared with WT littermates (Figure 1, B and C). Consistent with protein expression results, the highest transcript levels were also found in line no. 1; Lmnb1 mRNA showed approximately 3.5- (line no. 1) and 1.5-fold (line no. 2) higher expression compared with WT (Figure 1D). Consequently, all of the following experiments were performed on line no. 1, the highest expressing line. Both transgenic lines with lamin B1 duplication were born healthy and indistinguishable from control littermates. Line no. 2 progressed with a milder and later onset phenotype compared with line no. 1. Line no. 2 did not exhibit any abnormal pathology up to 12 months of age.

Figure 1. Generation of Lmnb1BAC mice.

(A) Map of the genomic insert in the BAC RP23-460J18 clone (RPCI library, C57BL/6J) used to generate mice with increased dosage of lamin B1 (Lmnb1BAC mice). The genomic insert is 177.20-kb long and contains the entire Lmnb1 locus. Black boxes represent lamin B1–coding sequences, and light gray lines indicate the BAC vector (pBACe3.6) sequence. Primers used for detection of the transgene are shown (T7 side: F1R1; SP6 side: F2, R2). (B) Representative Western blot of lamin B1 and α-tubulin in hemibrain lysates from Lmnb1BAC lines and WT mice at 12 months of age. (C) Quantification of Western blots normalized to α-tubulin. (D) qRT-PCR of lamin B1 transcript levels normalized to GAPDH from corresponding Lmnb1BAC mice hemibrains. Error bars represent mean ± SEM from 4 independent experiments.

ADLD mouse model exhibits cognitive impairment and age-dependent motor deficits.

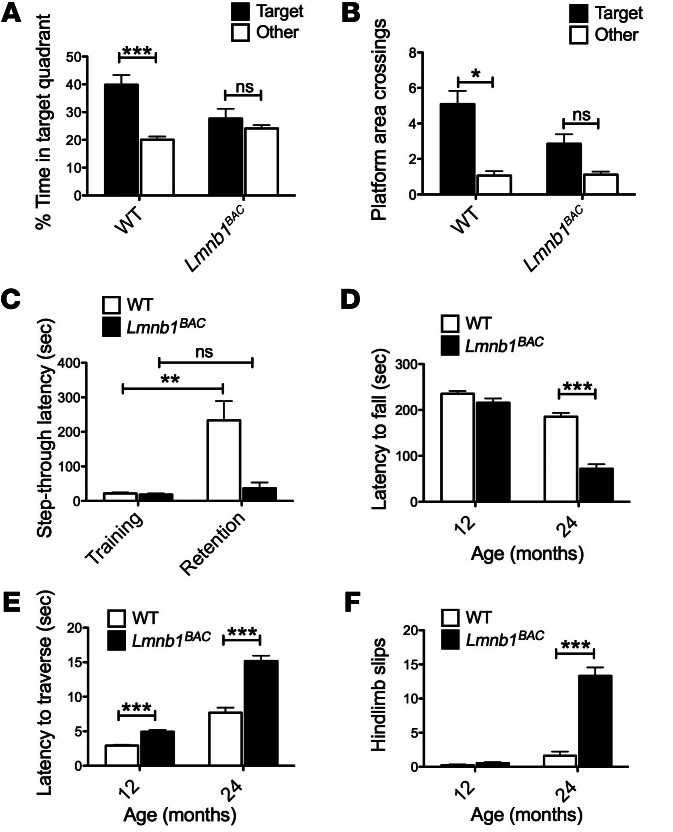

Cognitive and motor deficits are both observed in ADLD patients. We performed Morris water maze (MWM) and passive avoidance (PA) tasks in Lmnb1BAC and WT mice to assess cognitive impairments at 12 months and accelerated rotarod and balance beam to measure motor deficits at 12 and 24 months of age. The MWM is an established paradigm for testing spatial memory in rodents (19–21). Lmnb1BAC mice exhibited substantial spatial memory deficits in an MWM assay compared with WT controls. WT mice exhibited a preference for the target quadrant where the platform was located during training compared with other quadrants (Figure 2A), indicating that they remembered the overall location of the platform. In contrast, Lmnb1BAC mice were impaired and did not spend more time in the target quadrant compared with others (Figure 2A). Analyses of virtual platform crossings during the probe test revealed that WT animals showed a clear preference for the target platform location (Figure 2B). Nonselective preferences for the target platform by Lmnb1BAC mice indicate that they do not recall the location of the hidden platform and are impaired in spatial memory retention (Figure 2B). Lmnb1BAC and WT animals performed equally well during the visible platform test and exhibited equal velocities, demonstrating that Lmnb1BAC animals were not visually impaired and that neither their cued reference memory nor their swimming was impaired (data not shown). In agreement with these findings, Lmnb1BAC mice exhibited impairments in a step-through PA task, which reflects long-term spatial associative learning and fear memory of an aversive experience. WT but not Lmnb1BAC mice showed substantial increase in the latency to avoid the light and step through the dark chamber where they received an electric shock the day before (P < 0.01) (Figure 2C). This indicated that Lmnb1BAC mice have spatial associative memory deficits compared with WT mice at 12 months of age. During training, the latencies to step through the dark chamber were not different among genotypes, indicating that all the mice showed the same level of spontaneous aversion to light. Together, these studies suggest cognitive and memory impairments in Lmnb1BAC mice.

Figure 2. A mouse model of ADLD exhibited cognitive and motor deficits.

Lmnb1BAC and WT mice were behaviorally tested to assess spatial and fear memory in the MWM and PA tests and motor functions in the rotarod and balance beam tests. (A and B) Lmnb1BAC mice exhibited spatial memory deficits in the MWM at 12 month of age. (A) Lmnb1BAC mice spent substantially less time in the target quadrant and (B) made less platform area crossings compared with WT during the probe trial. (C) Lmnb1BAC mice failed to recall an aversive experience made on the previous day on the PA test and exhibited decreased step-through latencies compared with WT mice at 12 months of age. The bars indicate the mean latencies to enter the dark compartment on the training day (white) and 24 hours later on the retention day (black). (D–F) Progressive deterioration of motor functions in Lmnb1BAC mice compared with WT mice, (D) Lmnb1BAC mice spent less time on the accelerated rotarod across all 8 trials at 24 but not at 12 months of age compared with WT. (E) Lmnb1BAC mice showed increased latency to traverse a 5-mm–wide balance beam at 12 months and progressively worsened at 24 month. (F) Lmnb1BAC mice also exhibited increased hind limb slips compared with WT controls. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. n = 10–14 per genotypic group. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Lmnb1BAC animals exhibited progressive motor impairment on 2 different motor tasks, the accelerated rotarod and balance beam.

The accelerated rotarod did not detect significant motor impairments at 12 months of age in Lmnb1BAC mice compared with WT. However, by 24 months of age, Lmnb1BAC mice were not able to remain on the rotarod as long as their WT counterparts (Figure 2D). The balance beam, typically a more sensitive test for gait impairment, detected gait deficits at 12 months and progressed to 24 months of age. Lmnb1BAC mice showed increased latency and number of hind limb slips to traverse a 42-cm beam that was 5 mm in diameter (Figure 2, E and F). Together, these data demonstrate age-dependent motor deficits in Lmnb1BAC animals.

Lamin B1 overexpression results in seizures in ADLD mice.

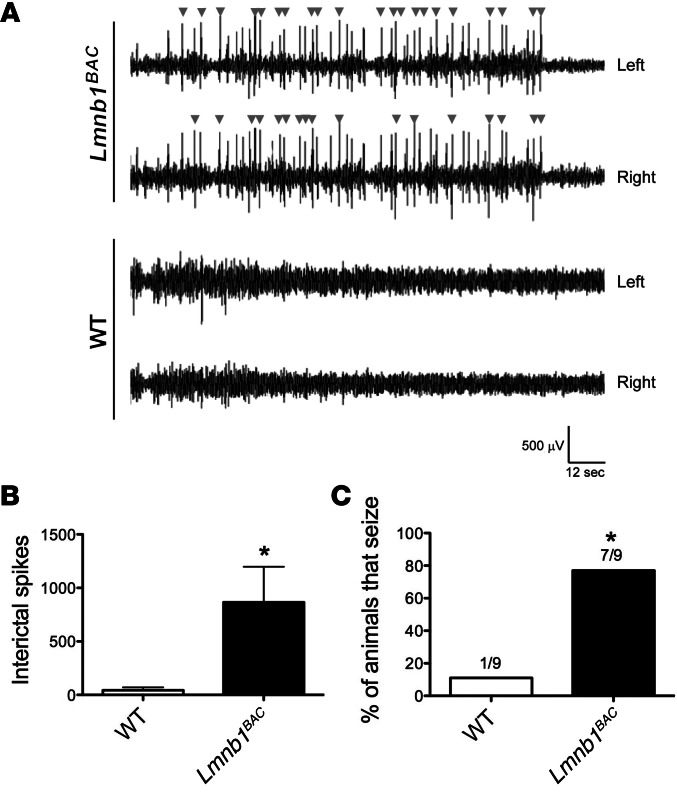

Recent studies report epilepsy in some patients with myelin diseases, including MS and inherited leukodystrophies such as PMD (22, 23). Murine models of some leukodystrophies exhibit epilepsy (24). In addition, some ADLD patients exhibit epilepsy (unpublished observations, Eric Huang). We observed frequent behavioral seizures in Lmnb1BAC animals, which varied from generalized spasms and tremors to generalized clonic activity with atonia and tail extension. To confirm these observations, we used EEG recording. Cortical EEG recordings revealed frequent spontaneous epileptic activity, including epileptiform discharges and seizures, in Lmnb1BAC mice but not in WT controls. Representative traces over 2 minutes, 30 seconds, of a 24-hour recording showed that Lmnb1BAC mice, but not WT mice, displayed frequent interictal spikes (arrowheads) in both left and right hemispheres (Figure 3A). Lmnb1BAC mice exhibited an approximately 20-fold increase in the number of interictal spikes compared with WT mice (Figure 3B). Given a subconvulsive dose of pentylenetetrazol (PTZ), a GABAA receptor antagonist, Lmnb1BAC animals were more susceptible to PTZ-induced seizures compared with WT controls. Seven out of nine Lmnb1BAC animals exhibited seizures within 5 to 7 minutes of drug administration compared with only 1 out of 9 WT animals (Figure 3C). These findings demonstrate that lamin B1 overexpression induces aberrant brain network activity, such as neuronal hypersynchrony and hyperexcitability, and predisposes animals to epilepsy.

Figure 3. Lamin B1 overexpression results in seizures.

Spontaneous EEG activity over the parietal cortex of Lmnb1BAC and WT mice was recorded for 24 hours. (A) EEG recordings from the left and right hemisphere, respectively, are shown for a representative transgenic mouse overexpressing lamin B1 (top traces) or a WT control (bottom traces). Arrowheads mark interictal spikes. (B) Quantification of interictal spikes over 24-hour recordings indicates the occurrence of spontaneous epileptiform activity in Lmnb1BAC mice specifically. n = 10 animals per genotypic group. (C) Histogram quantifying percentage of animals seizing after the administration of 30 mg/kg of PTZ. n = 9 animals per genotypic group. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

Lamin B1 overexpression results in aberrant myelin formation, axonal degeneration, and demyelination.

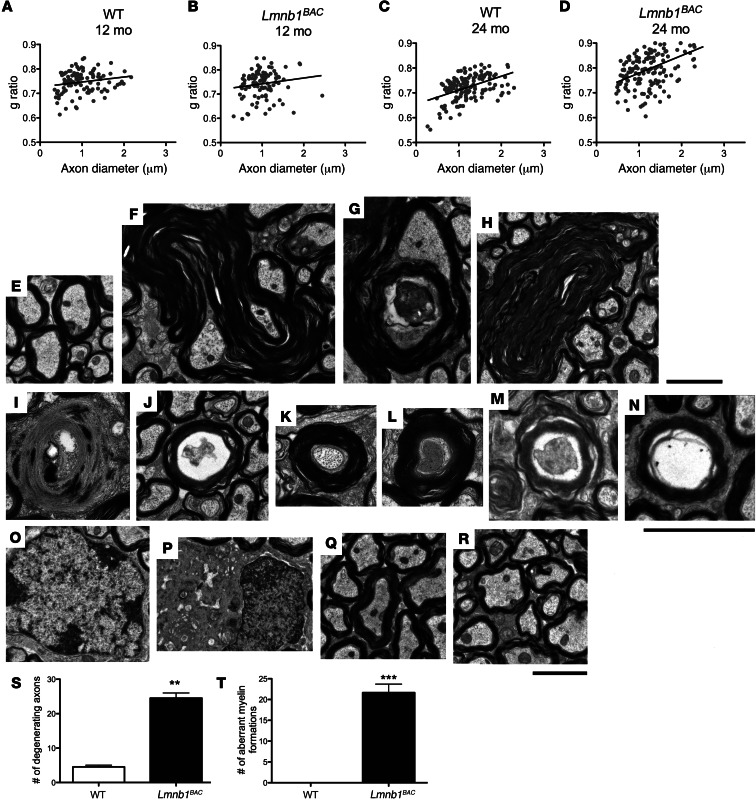

To address whether lamin B1 overexpression is associated with myelin pathology, we examined myelin integrity by electron microscopy in 12- and 24-month-old Lmnb1BAC and WT mice. Because pathologic studies show greatest loss of white matter in pyramidal tracts of ADLD patients (25), we performed ultrastructural analysis on pyramidal tracts in the brain region of the pons. Although these ultrastructural analyses did not identify overall demyelination in 12-month-old animals assessed by g ratio (the ratio between the diameter of the inner axon and the total outer diameter [Figure 4, A and B]), they did identify such demyelination, however, by 24 months compared with WT controls (Figure 4, C and D). Ultrastructural analyses reveal a variety of aberrant structures, which were generally dominated by outfoldings, extensions, and invaginations originating from the myelin sheath. Aberrant myelin loops consisted of multiple loops within the same myelinated axon, which may result from a retrograde inversion of a single infolding, since axonal material can be seen in the gap between the inner and outer infoldings (Figure 4, F and G, 12-month-old animals; Figure 4H, 24-month-old Lmnb1BAC animals). These morphological abnormalities were not seen in WT mice (Figure 4, E and Q, 12 and 24-month-old animals, respectively). Apart from these abnormalities of the myelin sheath, axonal disintegration and even degradation of the entire axon-myelin unit was observed at a significantly higher level compared with that in WT controls (Figure 4, I and J, 12-month-old animals; Figure 4, M and N, 24-month-old animals). Additionally, hypermyelinated fibers (Figure 4, K and L, 12-month-old animals) were also observed. Frequent dying and degenerating oligodendrocytes were also noted in the 24-month-old Lmnb1BAC animals (Figure 4P), which corresponded with demyelinated axons (Figure 4R) compared with WT controls (Figure 4, O and Q). Toluidine blue staining of adjacent sections showed similar findings of demyelination and aberrant structures in 24-month-old Lmnb1BAC animals (Supplemental Figure 1; supplemental material available online with this article; doi: 10.1172/JCI66737DS1). Quantification of approximately 150 to 200 axons for each group at 12 months of age showed significant axonal degeneration and aberrant myelin formation in Lmnb1BAC animals compared with WT controls (Figure 4, S and T), similar to observations found in some other myelin disorders (26–28). Because inflammation is seen in active MS lesions, we additionally assessed Iba1 and GFAP immunostaining for microglia activation and reactive astrocytes, respectively, in various regions of the brain, including cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum in 12-month-old Lmnb1BAC and control animals. There were no differences in the cortex (Supplemental Figure 2), hippocampus, or cerebellum (data not shown). These data are consistent with ADLD patient data showing no obvious inflammation.

Figure 4. Lamin B1 overexpression results in aberrant myelin formation, axonal degeneration, and demyelination.

Ultrastructural analysis was performed on pyramidal tracts of 12- and 24-month-old Lmnb1BAC and corresponding WT mice. (A and B) g ratio analyses at 12 and (C and D) 24 months, at which time demyelination is prominent in Lmnb1BAC mice. P < 0.05. (E) WT controls at 12 months. (F and G) Ultrastructural analyses revealed numerous aberrant structures, which included outfoldings, extensions, and invaginations originating from the myelin sheath at 12 months and (H) at 24 months. (I and J) Axonal disintegration and degradation of the entire axon-myelin unit was observed at a significantly higher level at 12 months and (M and N) at 24 months compared with WT controls. (K and L) Hypermyelinated fibers and dying axons were also observed in Lmnb1BAC mice at 12 months of age. (O) Normal oligodendrocyte and (Q) normal compact myelin at 24 months of age in control animals. (P) Representative of frequent dying and degenerating oligodendrocytes in 24-month-old Lmnb1BAC mice. Dying oligodendrocytes correlate with increased (R) irregular and demyelinated fibers in 24-month-old Lmnb1BAC animals. (S and T) Quantification of approximately 150 to 200 axons for 12-month-old Lmnb1BAC mice exhibited significant axonal degeneration and aberrant myelin formations compared with WT controls. n = 3 animals per genotype. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Scale bars: 2 μm.

Lamin B1 overexpression induces cell-autonomous neuropathology in oligodendrocytes.

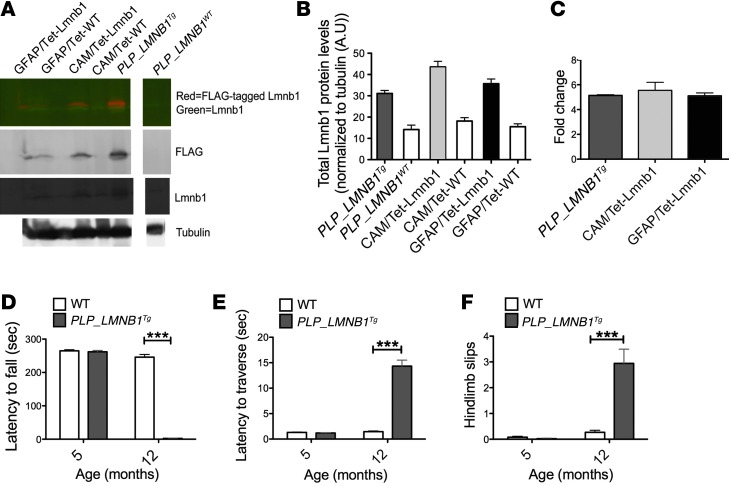

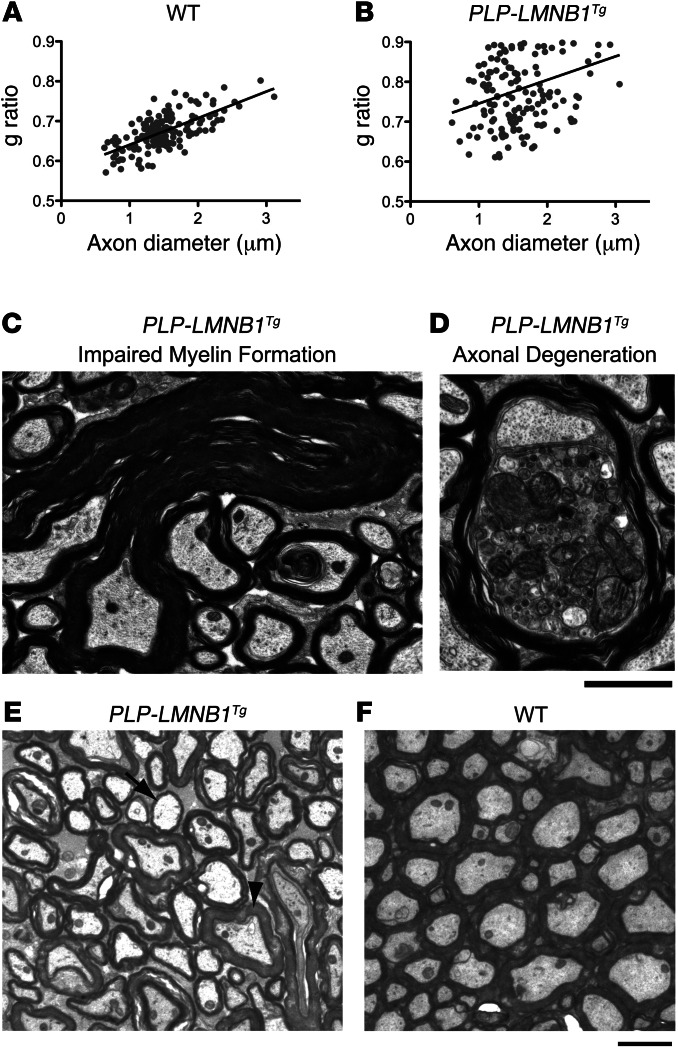

An interesting feature of ADLD is specific demyelination in the presence of ubiquitously overexpressed lamin B1 protein. To investigate the pathologic consequences of lamin B1 overexpression on different cell lineages in the brain, we overexpressed a FLAG-tagged lamin B1 selectively in oligodendrocytes, neurons, and astrocytes driven by cell-specific promoters (Plp1, Camk2a, and GFAP, respectively). Each of these lines showed expression levels of lamin B1 that were similarly higher than their WT counterparts, which were quantified by Western blot analyses and qRT-PCR at 12 months of age (Figure 5, A–C). Western blot analysis of total lamin B1 showed on average a 2.2-, 2.4-, and 2.3-fold increase in mice where Lmnb1 was driven by Plp1, Camk2a, and GFAP, respectively, compared with WT controls (Figure 5, A and B). Overexpression levels were consistent with what was observed in ADLD patients, which exhibit on average a 2-fold increase (1, 11). For reasons we do not completely understand, endogenous lamin B1 appeared to increase as a result of lamin B1 overexpression compared with WT controls (Supplemental Figure 3A). mRNA by qRT-PCR analyses also exhibited marked and comparable increases in all 3 cell-specific lines (Figure 5C). Only animals overexpressing lamin B1 in oligodendrocytes (PLP-LMNB1Tg) exhibited age-dependent motor deficits beginning at 10 months (observed) and rapidly progressing to 12 months of age, at which time these animals became moribund. At 5 months, PLP-LMNB1Tg animals showed no differences on the accelerated rotarod or on an 11-mm–wide balance beam compared with WT controls (Figure 5, D–F). However, by 12 months, PLP-LMNB1Tg animals exhibited considerable decreased latency to fall on the accelerated rotarod (Figure 5D) and showed marked increased latency to traverse the balance beam compared with WT controls (P < 0.001) (Figure 5E). Additionally, PLP-LMNB1Tg animals exhibited more hind limb slips (Figure 5F). These motor deficits observed in the PLP-LMNB1Tg mice were accompanied by demyelination, aberrant myelin formation, and axonal degeneration (Figure 6, B–D). Among aberrant myelin loops in PLP-LMNB1Tg animals, myelin-axon structure was also irregular and nonuniform compared with WT controls (Figure 6, E and F). Interspersed within areas of demyelinated axons (e.g., Figure 6E, arrow) were axons with normal myelin thickness (e.g., Figure 6E, arrowhead). The heterogeneity of myelin thicknesses is represented by the g ratio (Figure 6B). WT controls did not exhibit demyelination or display aberrant myelin loops (Figure 6, A and F). Toluidine blue staining of adjacent sections showed similar findings of demyelination and aberrant structures in PLP-LMNB1Tg mice (Supplemental Figure 1). The neuropathology and age-dependent motor deficits observed in PLP-LMNB1Tg animals may more accurately reflect mechanisms related to degeneration in ADLD. Consistent with the global overexpressing Lmnb1BAC mice, PLP-LMNB1Tg animals also exhibited spontaneous seizures (data not shown). Animals overexpressing lamin B1 specifically in neurons (CAM/tet-Lmnb1) and astrocytes (GFAP/tet-Lmnb1) showed no motor deficits on the balance beam and accelerated rotarod at 12 months and no overt behavioral abnormalities beyond 1 year (Supplemental Figure 3, B and C, respectively). Together, these results indicate that oligodendrocytes are inherently more vulnerable to the overexpression of lamin B1 than other cell types.

Figure 5. Lamin B1 overexpression in oligodendrocytes results in progressive motor impairment and myelin deficits.

(A) Representative Western blot for lamin B1, FLAG-tagged lamin B1, and α-tubulin in hemibrain lysates from transgenic mouse lines overexpressing lamin B1 selectively in oligodendrocytes, neurons, and astrocytes driven by cell-type–specific promoters (Plp1, Camk2a, and GFAP, respectively) vs. control mice at 12 months of age (lanes are discontinuous). Dual color detection with IR fluorescence for antibody against lamin B1 (green) and antibody against FLAG-tagged lamin B1 (red; top panel). Individual detection against FLAG (second panel), lamin B1 (third panel), and α-tubulin (bottom panel). (B) Quantification of Western blots of total lamin B1 normalized to α-tubulin. (C) qRT-PCR of lamin B1 transcript levels normalized to GAPDH from corresponding cell-specific hemibrains at 12 months of age. Error bars represent mean ± SEM from 3–4 independent experiments. (D–F) Animals overexpressing lamin B1 selectively in oligodendrocytes (PLP-LMNB1Tg) exhibited progressive motor deficits on the accelerated rotarod and balance beam. (D) PLP-LMNB1Tg mice had shortened latency to fall on the accelerated rotarod and (E) exhibited increased latency to traverse an 11-mm–wide balance beam with (F) hind limb slips. Values are expressed as means ± SEM, n = 10–12 per group. ***P < 0.001.

Figure 6. PLP-LMNB1Tg mice exhibit demyelination, aberrant myelin formation, and axonal degeneration.

(A and B) PLP-LMNB1Tg animals exhibited demyelination compared with WT controls, quantified by g ratio of 150–200 axons, P < 0.05. (C and D) PLP-LMNB1Tg animals showed aberrant myelin formation and axonal degeneration. (E and F) Demyelinating axons (e.g., arrow) and axons with normal myelin thickness (e.g., arrowhead) were frequently observed in PLP-LMNB1Tg mice (E) but not in WT controls (F). Myelin-axon structure also appeared irregular and nonuniform in PLP-LMNB1Tg mice compared with WT controls. n = 4 animals per genotype. Scale bars: 2 μm.

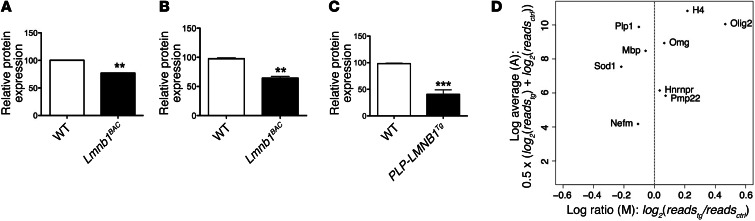

Lamin B1 overexpression results in significant decrease of the highly abundant myelin protein PLP.

We used quantitative mass spectrometry iTRAQ labeling to compare hindbrain protein levels from 12-month-old Lmnb1BAC and WT mice. Out of 500 proteins identified at 95% confidence interval of high-quality scoring peptide candidates, only 4 proteins showed substantial changes (P < 0.05). The heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (HNRNPN) and histone H4 (H4) were increased by 20% and 30%, respectively, while neurofilament medium polypeptide protein (NEFM) was reduced by 20%. Interestingly, PLP was reduced by 30% (Figure 7A). Decreased Plp1 expression was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Figure 7B). Mice overexpressing lamin B1 specifically in oligodendrocytes (PLP-LMNB1Tg) exhibited further reduction in PLP transcript levels (Figure 7C). However, mice overexpressing lamin B1 specifically in neurons (CAM/tet-Lmnb1) did not show any changes in Plp1 levels compared with WT controls (Supplemental Figure 3D).

Figure 7. Lamin B1 overexpression results in the decrease of the highly abundant myelin protein PLP.

(A) Quantitative mass spectrometry iTRAQ labeling of hindbrains from 12-month-old Lmnb1BAC mice and WT mice identified PLP at 95% confidence interval of high-quality scoring peptide candidates to be 30% downregulated in Lmnb1BAC animals compared with WT controls. (B) This finding was validated by qRT-PCR. (C) Mice overexpressing lamin B1 specifically in oligodendrocytes (PLP-LMNB1Tg) exhibited a further reduction in Plp1 transcript levels. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3 per group. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (D) Transcriptome analysis performed on purified oligodendrocytes validated proteomic changes including decreased Pol II binding to the Plp1 promoter in Lmnb1BAC mice compared with WT controls. Lamin B1 also regulates additional genes. x axis defined as M: log differential-expression ratio (log fold change); y axis defined as A: average log intensity (reads per kb of gene length) from oligodendrocytes between Lmnb1BAC mice and WT controls.

In addition, we performed transcriptome analysis by identifying Pol II–binding sites on a genome-wide scale from oligodendrocytes purified from Lmnb1BAC and WT control mice. Pol II binding was changed on promoters of a wide variety of genes. However, Pol II binding validated proteomic changes, including identifying decreased Pol II binding to the Plp1 promoter in Lmnb1BAC mice compared with WT controls (Figure 7D). Together, these 2 independent approaches suggest that lamin B1 overexpression results in altered gene expression and specifically suggest that a highly abundant myelin protein gene, Plp1, is reduced at the transcriptional level. This lowered Plp1 transcription level serves as an entry point for studies aimed at understanding pathophysiology in ADLD. We hence sought to further examine how lamin B1 overexpression leads to altered PLP1 transcription.

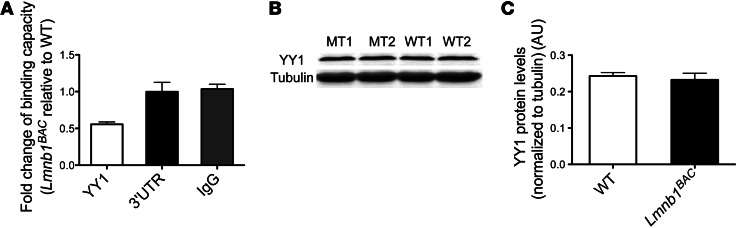

Loss of binding occupancy of YY1 to Plp1 promoter.

Alteration of gene transcription can result from many mechanisms, including changes in transcription factor binding and occupancy in the promoter region of the affected gene. In an effort to identify potential factors that contribute to the altered gene regulation of Plp1, we performed quantitative ChIP using known transcription factor candidates of the Plp1 promoter from hindbrains of 12-month-old Lmnb1BAC and WT mice. We identified YY1, a known transcriptional activator of Plp1 (18), as binding and occupying the Plp1 promoter significantly less in Lmnb1BAC hindbrains than in WT controls (Figure 8A). No differences were found in ChIP reactions performed by IgG antibody or real-time PCR for Plp1 3′ UTR, demonstrating the specific changes of YY1 binding to the Plp1 promoter (Figure 8A). We next asked whether decreased binding of YY1 to the Plp1 promoter resulted from reduced YY1 levels. We measured total protein levels of YY1 in hindbrains of 12-month-old mice and found no difference among genotypes (Figure 8, B and C). Taken together, these results indicate that overexpression of lamin B1 affects myelin-producing cells through the misregulation of Plp1 gene expression, in part via the transcription factor YY1.

Figure 8. Lamin B1 overexpression results in reduced binding occupancy of YY1 to Plp1 promoter.

(A) Quantitative ChIP coupled to PCR revealed a reduction in YY1 binding to the Plp1 promoter in hindbrains from 12-month-old Lmnb1BAC mice compared with WT controls normalized to 2% input. Primers were designed to amplify 150–200 bp containing either a consensus YY1-binding site or 3′ UTR. 3′ UTR and IgG were used as controls. (B) Representative blot of YY1 total protein levels normalized to α-tubulin in hindbrains of 12-month-old Lmnb1BAC and WT mice. (C) Quantification of YY1 protein level relative to α-tubulin was found not to be markedly different between Lmnb1BAC and WT mice. n = 4 per group of at least 2 independent experiments. P > 0.05.

Discussion

Duplication of the gene encoding lamin B1 causes ADLD. Here, we demonstrate that overexpression of lamin B1 in mice recapitulates many key features of ADLD. Lmnb1BAC mice exhibit spontaneous seizures, cognitive impairments, and age-dependent motor deficits similar to what is observed in ADLD patients. Ultrastructural analysis revealed aberrant myelin foldings eventually leading to myelin and axonal degeneration in Lmnb1BAC mice. Although lamin B1 is broadly expressed in Lmnb1BAC mice, we found that specific overexpression of lamin B1 in oligodendrocytes (PLP-LMNB1Tg mice) was sufficient to induce similar abnormalities, suggesting a cell-autonomous mechanism linking lamin B1 to myelin defects. Quantitative proteomic analysis of Lmnb1BAC mice revealed substantial reduction in PLP protein levels relative to WT controls (P < 0.05). Consistent with these results, we found that both RNA Pol II binding on the Plp1 promoter and transcript levels of Plp1 were downregulated in Lmnb1BAC animals. Finally, using quantitative ChIP assays, we discovered that YY1, a transcriptional activator of Plp1, was found at markedly reduced levels at Plp1 promoters. Taken together, these data suggest that the effects of lamin B1 overexpression are manifested, at least in part, through altered transcription of a gene known to play a key role in maintenance of the myelin sheath.

Although seizures have long been recognized to be part of the disease spectrum of MS, epileptiform activity is not a major feature in inherited leukodystrophies. One explanation may be that these are rare diseases with a general lack of EEG data in affected individuals. A more careful search for electrographic abnormalities is leading to an increase awareness of seizures in some leukodystrophies (22, 29). Among inherited leukodystrophies in children, 49% were noted to have epilepsy (30). The precise pathogenesis of epileptic seizures in inherited leukodystrophies is not well understood. Cognitive decline has been shown to correlate with cortical pathological severity and seizures in MS (31). An increased risk of seizures may also be associated with ADLD; a possible mechanism could be damage to the brain parenchyma leading to seizure susceptibility. Alternatively, the effects of demyelination on the cortex could cause cortical hyperexcitability resulting from altered axonal signaling.

PMD is an X-linked demyelination disorder typically caused by duplications of PLP1. How duplication of PLP1 leads to PMD remains unclear. However, recent studies showed that much of the PLP being produced from the higher gene dosage fails to be incorporated into the myelin sheath in a mouse model of PMD duplication (32). Consistent with this finding, we found that overexpression of lamin B1 also results in substantial decrease of PLP. Disease characteristics of ADLD and PMD, while overlapping, are not identical, suggesting that pathophysiology of these diseases is not solely due to decreased PLP. Our observation that Plp1 transcript levels are reduced as early as 11 weeks (data not shown), while behavioral impairments and myelin defects are not seen until 1 year of age in Lmnb1BAC animals, further suggests that PLP downregulation alone is insufficient to explain the ADLD-like phenotypes. Rather, PLP downregulation is likely to initiate a pathological myelin state that is exacerbated as animals age and trigger multiple mechanisms.

Considering that lamin B1 overexpression is likely to affect transcriptional activity of a number of genes, ADLD is probably the consequence of misregulation of a subset of genes, including PLP, which together bring about the features of ADLD. Consistent with this hypothesis, our transcriptome analysis points to several other gene candidates: for instance, we found that superoxide dismutase 1 (Sod1), an important regulator of superoxide radicals, was transcriptionally downregulated while the oligodendrocyte lineage transcription factor 2 (Olig2), a transcription factor known to be important for oligodendrocyte development, was upregulated upon lamin B1 overexpression (Figure 7D).

The precise mechanism through which lamin B1 overexpression leads to a specific downregulation of PLP is not yet known. However, nuclear lamins are known to regulate gene expression, in part through interactions with chromatin and repression of transcription. Previous studies have shown that nuclear lamins interact with DNA, histones, transcription factors, and chromatin proteins. Direct interaction of DNA with nuclear lamins causes downregulation of genes locally (33–35). Moreover, depletion of lamin B1 in Drosophila led to an upregulation of lamina-associated genes (36), specifically showing a direct role for lamin B1 in gene repression. We found a reduction in YY1 occupancy at Plp1 promoters in lamin B1–overexpressing animals with no change to the overall total protein level of YY1. It is therefore plausible that overexpression of lamin B1 pulls the Plp1 promoter region into a heterochromatin-like state and reduces accessibility of these regions to the YY1 transcription factor. Additionally, YY1 has previously been proposed to facilitate the attachment of the PLP1 promoter region to transcriptionally active domains of the nuclear matrix (18). Our observation that histone H4 levels were increased upon lamin B1 overexpression also supports the idea that lamin B1 overexpression leads to repressed transcription in specific genomic regions.

Together, these findings implicate lamin B1 as a modulator of myelin and genes involved in premature myelin breakdown, particularly in the aging process. Lamin B1 and its myelin-specific regulatory targets are therefore potential therapeutic avenues for remyelination in various demyelinating disorders.

In summary, we provide a valid murine model of ADLD that recapitulates human ADLD. Collectively, our results implicate an important role for lamin B1 in modulation of genes involved in normal myelin regulation, which may provide further elucidation of the molecular mechanisms that underlie a spectrum of myelin-related disorders including leukodystrophies, laminopathies, and multiple sclerosis. Ultimately, there is hope that such insights may provide novel potential therapeutic strategies for disorders of myelin.

Methods

Animals and generation of transgenic mice

All animals were housed in cages grouped by sex and provided with food and water ad libitum. Animals were housed under specific pathogenic–free conditions with a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle maintained at 23°C. Behavioral testing occurred between 8 am and 5 pm during the light cycle. Experiments were blind to mouse genotype and treatment during testing.

Lmnb1BAC.

For transgenesis, a large genomic insert (177.20 kb) containing the entire mouse Lmnb1 locus and cloned into the BAC vector pBACe3.6 was isolated from a mouse BAC genomic library (BAC RP23-460J18 clone; RPCI library, C57BL/6J). Purified BAC DNA was used for microinjection into the pronuclei of fertilized oocytes of C57BL/6J mice and was maintained on a C57BL/6J genetic background.

PLP-LMNB1Tg.

We generated transgenic mice encoding a FLAG-tagged human lamin B1 cDNA, which was cloned into a PLP promoter-exon expression cassette as previously described (37). The purified construct was then used for microinjection into the pronuclei of fertilized oocytes of FVB mice and was maintained on an FVB genetic background.

CAM/tet-Lmnb1 and GFAP/tet-Lmnb1.

Double-transgenic mice (CAM/tet-Lmnb1 and GFAP/tet-Lmnb1) were generated by crossing Camk2a tTA and GFAP-tTA mice (38, 39), respectively (B6/CBA genetic background), to a FLAG-tagged tetracycline-responsive element (TRE)-Lmnb1 mice (FVB). Both lines were maintained separately and crossed to generate F1 mice hemizygous for each transgene.

Behavioral testing

MWM.

Lmnb1BAC and WT mice were tested using the MWM, as described (40). In brief, over a number of trials, animals were trained to find a hidden platform in the MWM using spatial cues. Memory was tested 24 hours afterwards by a probe trial in which the hidden platform was removed and the amount of time and number of platform area crossings were quantified.

PA.

The PA test was used as previously described (41). A light/dark chamber with a sliding trap door separating the 2 chambers was used. Briefly, animals were allowed to acclimate for 15 seconds in the light compartment. Once mice stepped through into the dark compartment they received a shock of 0.3 mA for a maximum of 2 seconds. The latency to enter the dark compartment was recorded. The memory-retention test was performed 24 hours later without shock. A maximum retention latency of 400 seconds was given to mice that did not enter the dark compartment before that time (Gemini Avoidance System).

Accelerated rotarod and balance beam.

To assess motor coordination and balance, animals were tested on the accelerated rotarod and balance beams as previously described (42). Animals were tested on 42-cm–long Plexiglas beams (5 mm wide and 11 mm wide). Latency to traverse each beam and hind limb slips were recorded. The accelerated rotarod was accelerated from 4 to 40 rpm over a period of 270 seconds, and the time spent on the drum was recorded for each mouse. Animals were tested 1 trial per day over 8 trials unless otherwise stated.

Video-EEG monitoring

EEG recordings were performed as previously described (43). Briefly, Teflon-coated silver wires were implanted into the subdural space over the left and right parietal cortices, and the left frontal cortex was used as a reference. EEG activity was recorded in freely moving mice with Harmonie 5.0b software (Stellate). The number of abnormal epileptiform spikes (sharp-wave discharges with amplitude exceeding 6 times the mean EEG amplitude and lasting 20–70 ms) was automatically detected by the Gotman spike detectors (Harmonie; Stellate) over 24 hours of recording. The latency to seize and the number of seizures were visually quantified.

PTZ challenge

PTZ (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in PBS. A dose of 30 mg/kg was administered intraperitoneally.

Transmission electron microscopy

Toluidine blue staining and g ratio analysis.

12-month-old animals were deeply anesthetized and intracardially perfused with 2% paraformaldehyde and 1.25% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4 (n = 3 per group for Lmnb1BAC mice, n = 4 per group for PLP-LMNB1Tg mice). Brains were postfixed in 2% osmium tetroxide in the same buffer, en block stained in 2% aqueous uranyl acetate, dehydrated, infiltrated, and embedded in LX-112 resin (Ladd Research Industries). For light microscopy,1.5 μm semi-thin sections of pyramidal tracts at the level of the pons near decussation were cut and stained with 0.5% Toluidine blue O in a Borax solution. Experiments were performed as previously described with the above modifications (44). The g ratio of axons in the area of interest was obtained as a ratio of the diameter of an axon over the diameter of axon plus associated myelin sheath as previously described (45). Approximately 150 to 200 axons for each group of 4 animals were used. Digitized and calibrated images were analyzed using ImageJ (NIH).

Expression analysis

qRT–PCR was performed by the ΔΔCt method normalized to GAPDH control using ABI Sybr Green/ROX gene-specific primers. Data were collected and analyzed with an ABI 7900HT machine and software. Total RNA was isolated from whole brains of 11-week-old, and 12-month-old mice (n ≥ 3/group) using an RNeasy isolation kit (QIAGEN). Total RNA was reverse transcribed using SuperScriptII Reverse Transcriptase according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen).

Primer sequences for GAPDH (46) and Plp1 (47) are as follows: Lmnb1 (spanning exons 2–3); forward sequence, 5′-CAGATTGCCCAGCTAGAAGC-3′; reverse sequence, 5′-CATTGATCTCCTCTTCATAC-3′.

Brain lysate and Western blotting

Brain lysates and Western blotting were performed as previously described (48). In brief, flash-frozen hemibrains were homogenized in RIPA buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 1% Nonidet P-40, pH 7.4) with protease inhibitors (PI) (Sigma-Aldrich). Supernatants were supplemented with 1% final SDS and 100 mM DTT, boiled, loaded on 7.5% or 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membrane. The primary antibodies YY1 (1:500, sc-1703; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), lamin B1 (1:50, sc-6216; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), and α-tubulin (1:5,000, Sigma-Aldrich T9026) were incubated overnight, followed by species-matched, infrared-labeled (IR-labeled) secondary anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies (dilution 1:5,000; Li-Cor Biosciences). Blot membranes were imaged using Odyssey IR Imaging system (Li-Cor Biosciences).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed as described previously (48). Briefly, hemibrains were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours, cryoprotected in 20% sucrose in 0.1 m phosphate buffer for an additional 24 hours at 4°C, frozen, and stored at –80°C until use. Free-floating 30-μm serial sections were processed with primary antisera against GFAP (1:1000, Millipore ab5804) and Iba1 (1:1000, Wako Chemical, 019-19741). Detection of immunoreactivity was performed using the Vectastain Elite kit (Vector Laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and sections were developed in ImmPACT DAB (Vector Laboratories) for visualization. Sections were mounted and dehydrated in graded alcohols and xylene. Coverslips were affixed with DPX (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Quantification of GFAP and Iba1 immunoreactivity were performed using NIH ImageJ software. Particle numbers were quantified with the “analyze particles” function in “threshold and measure” functions with the scale standardized to the scale bar and set globally. Experiments used n = 3 per group for a total of 7–10 sections per animal and 2 fields of view per section.

Quantitative ChIP PCR

ChIP assays were performed with the SimpleChIP-Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Cell Signaling) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Brain lysates were prepared in PBS with PIs. Samples of input DNA were prepared in the same manner. Cell lysates were sonicated and immunoprecipitated with normal IgG or specific antibody against YY1 (sc-1703; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.). The DNA thus obtained was analyzed by real-time PCR with a set of primers directed against the Plp1 promoter region containing the YY1 consensus site (18). Plp1 3′ UTR was used as a negative control. PCR reactions were performed in triplicate in the presence of SYBR Green (Roche Diagnostics).

iTRAQ analysis

iTRAQ analysis was performed as previously described (49). Isolated hindbrain protein powders were dissolved in 50 μl of iTRAQ dissolution buffer (20-fold diluted, final concentration = 25 mM, pH 8.5), and protein concentrations were measured using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). 40 μg of protein for each sample was labeled for each iTRAQ experiment (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The final mixture of labeled samples was desalted and purified using an MCX cartridge (Mixed-mode Cation Exchange, Oasis solid phase extraction, 30 μm, 3 cc, 60 mg). They were then subjected to HPLC fractionation and mass spectrometry analysis.

Transcriptome analysis

OPC purification.

Purification of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) from P7-8 Lmnb1BAC mice or WT was carried out as described previously (50). In brief, OPCs were cultured in proliferation medium (+PDGF10 ng/ml +NT3, 1 ng/ml) for 6 days followed by differentiation medium (40 ng/ml triiodothyronine) for 4 days. OPCs were fixed with 1% formaldehyde solution and frozen immediately at –80°C before the ChIP-Seq using the RNA polymerase II antibody (Active Motif).

Data analysis.

Analysis of Pol II–binding sites on a genome-wide scale from oligodendrocytes purified from Lmnb1BAC and WT control mice were normalized by the total number of reads between the transgenic and the control samples. For each mouse gene defined by Ensembl, including 2-kb upstream and 6-kb downstream regions, we counted the number of reads pulled down by Pol II in ChIP-Seq. The count was then divided by the genomic length (in unit of kb) of the gene. The reads per kb of gene length were used as an estimate of the strength of expression.

Statistics

Comparisons of different groups (between genotypes) were performed on experiments requiring nonrepeated trials using 2-tailed independent t tests and regression analysis. Repeated measures t test with between-subject factor for genotype and repeated measures for training were performed on experiments for behavioral tests requiring repeated trials. There were no interactions observed between genotype and training. If there was no effect from repeated training, trials were collapsed, and a 2-tailed t test was performed. Paired t test was performed when animals were subjected to different behavioral conditions in a given paradigm. All t tests and P values presented were performed from 2-tailed tests. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The Huynh-Feldt adjustment was used in correcting for the violation of sphericity when necessary to adjust nonuniform variance across days or groups. Data were analyzed with IBM SPSS 20.0.

Study approval

All procedures were conducted in strict compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted by the NIH and were approved by the University of California San Francisco.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jinny Wong and Junli Zhang from the Electron Microscopy and Transgenic Gene Targeting Cores, respectively, at the J. David Gladstone Institutes. The authors also recognize the Center for Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics at the University of Minnesota and various supporting agencies, including the National Science Foundation for Major Research Instrumentation grants 9871237 and NSF-DBI-0215759 used to purchase the instruments described in this study. This work was supported by NIH grants F32 NS066722-01A1 to M.Y. Heng, and a fellowship from the A.P. Giannini Foundation to M.Y. Heng; NIH NS062733 to Y.H. Fu, and the Sandler Neurogenetics Fund to Y.H. Fu and L.J. Ptácχek. L.J. Ptácχek is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Citation for this article: J Clin Invest. 2013;123(6):2719–2729. doi:10.1172/JCI66737.

Quasar S. Padiath’s present address is: Department of Human Genetics, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

Ying Tong’s present address is: College of Life Sciences, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan, China.

References

- 1.Padiath QS, et al. Lamin B1 duplications cause autosomal dominant leukodystrophy. Nat Genet. 2006;38(10):1114–1123. doi: 10.1038/ng1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nave KA. Myelination and support of axonal integrity by glia. Nature. 2010;468(7321):244–252. doi: 10.1038/nature09614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nave KA, Trapp BD. Axon-glial signaling and the glial support of axon function. Annu Rev of Neurosci. 2008;31:535–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodward KJ. The molecular and cellular defects underlying Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2008;10:e14. doi: 10.1017/S1462399408000677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garbern JY, et al. Patients lacking the major CNS myelin protein, proteolipid protein 1, develop length-dependent axonal degeneration in the absence of demyelination and inflammation. Brain. 2002;125(pt 3):551–561. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson TJ, et al. Late-onset neurodegeneration in mice with increased dosage of the proteolipid protein gene. J Comp Neurol. 1998;394(4):506–519. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19980518)394:4<506::AID-CNE8>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffiths I, et al. Axonal swellings and degeneration in mice lacking the major proteolipid of myelin. Science. 1998;280(5369):1610–1613. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenbluth J, Nave KA, Mierzwa A, Schiff R. Subtle myelin defects in PLP-null mice. Glia. 2006;54(3):172–182. doi: 10.1002/glia.20370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broers JL, Ramaekers FC, Bonne G, Yaou RB, Hutchison CJ. Nuclear lamins: laminopathies and their role in premature ageing. Physiol Rev. 2006;86(3):967–1008. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00047.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schumacher J, Reichenzeller M, Kempf T, Schnolzer M, Herrmann H. Identification of a novel, highly variable amino-terminal amino acid sequence element in the nuclear intermediate filament protein lamin B(2) from higher vertebrates. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(26):6211–6216. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin ST, Ptacek LJ, Fu YH. Adult-onset autosomal dominant leukodystrophy: linking nuclear envelope to myelin. J Neurosci. 2011;31(4):1163–1166. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5994-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Worman HJ, Ostlund C, Wang Y. Diseases of the nuclear envelope. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(2):a000760. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostlund C, Worman HJ. Nuclear envelope proteins and neuromuscular diseases. Muscle Nerve. 2003;27(4):393–406. doi: 10.1002/mus.10302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gruenbaum Y, Margalit A, Goldman RD, Shumaker DK, Wilson KL. The nuclear lamina comes of age. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(1):21–31. doi: 10.1038/nrm1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malhas A, Lee CF, Sanders R, Saunders NJ, Vaux DJ. Defects in lamin B1 expression or processing affect interphase chromosome position and gene expression. J Cell Biol. 2007;176(5):593–603. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200607054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vergnes L, Peterfy M, Bergo MO, Young SG, Reue K. Lamin B1 is required for mouse development and nuclear integrity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(28):10428–10433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401424101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peric-Hupkes D, et al. Molecular maps of the reorganization of genome-nuclear lamina interactions during differentiation. Mol Cell. 2010;38(4):603–613. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berndt JA, Kim JG, Tosic M, Kim C, Hudson LD. The transcriptional regulator Yin Yang 1 activates the myelin PLP gene. J Neurochem. 2001;77(3):935–942. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Hooge R, De Deyn PP. Applications of the Morris water maze in the study of learning and memory. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;36(1):60–90. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(01)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallagher M, Burwell R, Burchinal M. Severity of spatial learning impairment in aging: development of a learning index for performance in the Morris water maze. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107(4):618–626. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.107.4.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris R. Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J Neurosci Methods. 1984;11(1):47–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang PJ, Hwu WL, Shen YZ. Epileptic seizures and electroencephalographic evolution in genetic leukodystrophies. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;18(1):25–32. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200101000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelley BJ, Rodriguez M. Seizures in patients with multiple sclerosis: epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(10):805–815. doi: 10.2165/11310900-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffiths I, Klugmann M, Anderson T, Thomson C, Vouyiouklis D, Nave KA. Current concepts of PLP and its role in the nervous system. Microsc Res Tech. 1998;41(5):344–358. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19980601)41:5<344::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melberg A, Hallberg L, Kalimo H, Raininko R. MR characteristics and neuropathology in adult-onset autosomal dominant leukodystrophy with autonomic symptoms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27(4):904–911. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Runker AE, et al. Pathology of a mouse mutation in peripheral myelin protein P0 is characteristic of a severe and early onset form of human Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 1B disorder. J Cell Biol. 2004;165(4):565–573. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200402087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tersar K, et al. Mtmr13/Sbf2-deficient mice: an animal model for CMT4B2. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(24):2991–3001. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edgar JM, et al. Early ultrastructural defects of axons and axon-glia junctions in mice lacking expression of Cnp1. Glia. 2009;57(16):1815–1824. doi: 10.1002/glia.20893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morse LE, Rosman NP. Myoclonic seizures in Krabbe disease: a unique presentation in late-onset type. Pediatr Neurol. 2006;35(2):154–157. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonkowsky JL, Nelson C, Kingston JL, Filloux FM, Mundorff MB, Srivastava R. The burden of inherited leukodystrophies in children. Neurology. 2010;75(8):718–725. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181eee46b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calabrese M, et al. Cortical pathology in multiple sclerosis patients with epilepsy: a 3 year longitudinal study. J Neurol Neurosug Psychiatry. 2012;83(1):49–54. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-300414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karim SA, et al. PLP/DM20 expression and turnover in a transgenic mouse model of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Glia. 2010;58(14):1727–1738. doi: 10.1002/glia.21043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finlan LE, et al. Recruitment to the nuclear periphery can alter expression of genes in human cells. PloS Genet. 2008;4(3):e1000039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pickersgill H, Kalverda B, de Wit E, Talhout W, Fornerod M, van Steensel B. Characterization of the Drosophila melanogaster genome at the nuclear lamina. Nat Genet. 2006;38(9):1005–1014. doi: 10.1038/ng1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reddy KL, Zullo JM, Bertolino E, Singh H. Transcriptional repression mediated by repositioning of genes to the nuclear lamina. Nature. 2008;452(7184):243–247. doi: 10.1038/nature06727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shevelyov YY, et al. The B-type lamin is required for somatic repression of testis-specific gene clusters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(9):3282–3287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811933106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuss B, et al. Purification and analysis of in vivo-differentiated oligodendrocytes expressing the green fluorescent protein. Dev Biol. 2000;218(2):259–274. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin W, et al. Interferon-gamma induced medulloblastoma in the developing cerebellum. J Neurosci. 2004;24(45):10074–10083. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2604-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayford M, Bach ME, Huang YY, Wang L, Hawkins RD, Kandel ER. Control of memory formation through regulated expression of a CaMKII transgene. Science. 1996;274(5293):1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris JA, et al. Many neuronal and behavioral impairments in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease are independent of caspase cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein. J Neurosci. 2010;30(1):372–381. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5341-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raber J, et al. Isoform-specific effects of human apolipoprotein E on brain function revealed in ApoE knockout mice: increased susceptibility of females. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(18):10914–10919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heng MY, Tallaksen-Greene SJ, Detloff PJ, Albin RL. Longitudinal evaluation of the Hdh(CAG)150 knock-in murine model of Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci. 2007;27(34):8989–8998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1830-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verret L, et al. Inhibitory interneuron deficit links altered network activity and cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer model. Cell. 2012;149(3):708–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kurrasch DM, Nevin LM, Wong JS, Baier H, Ingraham HA. Neuroendocrine transcriptional programs adapt dynamically to the supply and demand for neuropeptides as revealed in NSF mutant zebrafish. Neural Dev. 2009;4:22. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fancy SP, et al. Dysregulation of the Wnt pathway inhibits timely myelination and remyelination in the mammalian CNS. Genes Dev. 2009;23(19):1571–1585. doi: 10.1101/gad.1806309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hashimoto T, Bazmi HH, Mirnics K, Wu Q, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Conserved regional patterns of GABA-related transcript expression in the neocortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(4):479–489. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07081223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin KY, Chen KM, Lan KP, Lee HH, Lai SC. Alterations of myelin proteins in inflammatory demyelination of BALB/c mice caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Vet Parasitol. 2010;171(1–2):74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heng MY, et al. Early autophagic response in a novel knock-in model of Huntington disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(19):3702–3720. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Akkina SK, Zhang Y, Nelsestuen GL, Oetting WS, Ibrahim HN. Temporal stability of the urinary proteome after kidney transplant: more sensitive than protein composition? J Proteome Res. 2009;8(1):94–103. doi: 10.1021/pr800646j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dugas JC, Tai YC, Speed TP, Ngai J, Barres BA. Functional genomic analysis of oligodendrocyte differentiation. J Neurosci. 2006;26(43):10967–10983. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2572-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.