Abstract

Magnesium-aluminum layered double hydroxides intercalated with antitumor drug etoposide (VP16) were prepared for the first time using a two-step procedure. The X-ray powder diffraction data suggested the intercalation of VP16 into layers with the increased basal spacing from 0.84–1.18 nm was successful. Then, it was characterized by X-ray powder diffraction, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, thermogravimetry and differential thermal analysis, and transmission electron microscopy. The prepared nanoparticles, VP16-LDH, showed an average diameter of 62.5 nm with a zeta potential of 20.5 mV. Evaluation of the buffering effect of VP16-LDH indicated that the nanohybrids were ideal for administration of the drugs that treat human stomach irritation. The loading amount of intercalated VP16 was 21.94% and possessed a profile of sustained release. The mechanism of VP16-LDH release in the phosphate buffered saline solution at pH 7.4 is likely controlled by the diffusion of VP16 anions from inside to the surface of LDH particles. The in vitro cytotoxicity and antitumor assays indicated that VP16-LDH hybrids were less toxic to GES-1 cells while exhibiting better antitumor efficacy on MKN45 and SGC-7901 cells. These results imply that VP16-LDH is a potential antitumor drug for a broad range of gastric cancer therapeutic applications.

Keywords: layered double hydroxides, etoposide, drug delivery, antitumor effect, sustained release

Introduction

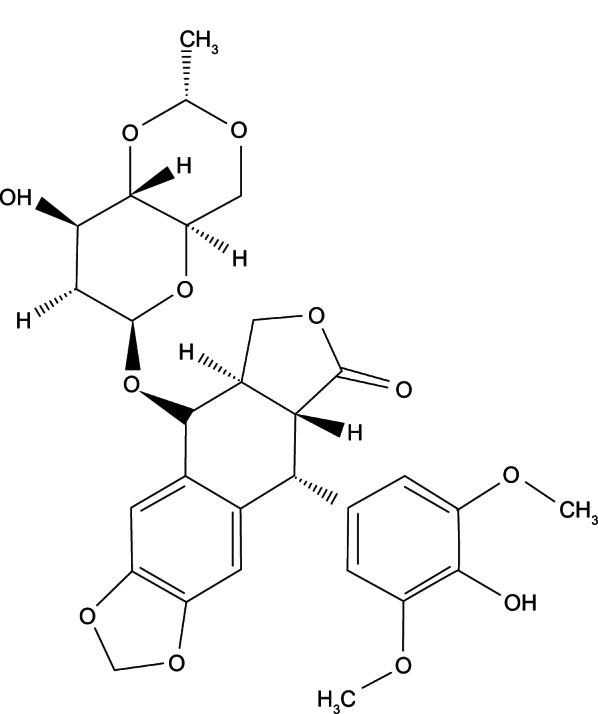

Etoposide (VP16) (Figure 1) is a semisynthetic derivative of podophyllotoxin, which acts by inhibition of one of the most abundant nuclear proteins, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) topoisomerase 2. Etoposide is cell cycle-specific and leads to an accumulation of cells in G2/M.1 Thus, it has a significant effect on a large range of carcinomas, particularly gastric cancer cells, small cell lung carcinoma, germ cell tumors, hematologic malignancies, and childhood malignancies. However, the inhibition of enzymes can only be saturated at high drug concentrations with prolonged exposure, which would lead to greater cytotoxicity.2–5 Moreover, deficiencies such as poor water solubility, metabolic inactivation, drug resistance, myelosuppression, and poor bioavailability have limited their scopes of applications.6–8 As a result, a drug delivery system may represent an attractive prospect for overcoming these pharmaceutical limitations and improving their clinical application.

Figure 1.

Molecular formula of etoposide (VP16).

Abbreviation: VP16, etoposide.

Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) are a family of anionic clay materials, exemplified by the natural mineral hydrotalcite [Mg6Al2(OH)16CO3 ⋅ 4H2O]. All LDH minerals found in nature and synthesized in the laboratory have a structure similar to that of hydrotalcite or its hexagonal analog, manasseite. The majority adhere to the general formula [M1−x2+Mx3+(OH2)][Ax/n] mH2O, where M2+ and M3+ represent divalent and trivalent cations octahedrally coordinated to hydroxyl ions, An− is the interlayer organic or inorganic anion with negative charge, M is the number of interlayer water molecules, and x = M3+/(M2+ + M3+) stands for the layer charge density of LDH.9,10 In recent years, LDHs have been found to have promising use in biomedicine. Their low cost, good biocompatibility, low toxicity to mammalian cells, controlled-release system, and ability to provide full protection for loaded drugs make them suitable candidates for drug delivery systems.11,12 Many LDH compounds intercalated with beneficial organic anions, such as deoxyribonucleic acid DNA,13–16 amino acids,17–22 anionic polymers,23 pesticides,24,25 and drugs,26–30 have been prepared successfully. Special interests have focused on exploring the possibilities of using LDH drug delivery systems to deliver antiinflammatory drugs,31 anticoagulants like heparin,32 or anticancer drugs.33,34 These studies involve some basic issues, including the intercalation (loading) of drugs or biomolecules into the LDH interlayer, the release behaviors of drugs or biomolecules from the LDH interlayer under different physiological conditions, the toxicity of LDH materials to cells, the cellular uptake of LDH nanoparticles, and cellular drug delivery tests. Furthermore, this drug delivery system can be modified to target specific cells or organs, thereby expanding its application range.

The aim of this paper was to intercalate the antitumor drug VP16 into the LDH interlayer and characterize the resultant nanohybrids with a set of tests. The buffer effect and release behavior were also evaluated. The in vitro cell cytotoxicity and antitumor assays showed VP16-LDH to be less toxic to GES-1 cells while providing better antitumor efficacy on MKN45 and SGC-7901 cells.

Materials and methods

Materials

Etoposide was a kind gift from the University of Science and Technology of China. Mg(NO3)2 ⋅ 6H2O, Al(NO3)3 ⋅ 9H2O, and tyrosine (Tyr) were purchased from the China National Medicine Group, Shanghai Chemical Reagents Company (Shanghai, People’s Republic of China), and were used without further purification. Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640, fetal calf serum, penicillin G, streptomycin, and trypsinase were obtained from Gibco-BRL (Life Technologies Corporation, Grand Island NY, USA). Dimethyl sulfoxide and MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Deionized water was decarbonated by boiling before use in all applications.

Preparation of nanohybrids

The nanohybrids were prepared using a two-step procedure, which we described previously.28,34 First, Tyr-LDH was prepared via the coprecipitation method under a nitrogen (N2) atmosphere, as is conventional to minimize or avoid contamination by atmospheric CO2.35 A mixed solution of 1 M Mg (NO3)2 ⋅ 6H2O and Al(NO3)3 ⋅ 9H2O (Mg:Al ratio of 3:1) was added dropwise to an aqueous solution of 1 M Tyr while vigorously stirring under a nitrogen atmosphere at room temperature. The pH of the resultant suspension was then adjusted to 10.0 ± 0.2 by adding 1 M NaOH solution dropwise while vigorously stirring at 80°C for 5 hours in a nitrogen-filled environment. This resulted in the formation of Tyr-LDH precipitates, which were then harvested by filtering, vacuum dried overnight, and used for subsequent investigations.

Second VP16-LDH nanohybrids were prepared via ion exchange. The freshly prepared Tyr-LDH suspension was added to a 0.1 M VP16 solution (pH previously adjusted to 12 using NaOH). The mixture was magnetically stirred continuously under a nitrogen atmosphere at 80°C for 5 hours. The resultant slurry was then filtered washed thoroughly with decarbonated water, and dried overnight. The product was denoted as VP16-LDH.

Characterization

X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded on a Rigaku Miniflex Diffractometer (Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) using CuKa radiation (λ = 0.154060 nm, 40 kV, 40 mA, step of 0.0330°). The average particle size (z-average size) and size distribution were measured using photon correlation spectroscopy (LS230, Beckman Coulter Inc, Brea, CA, USA) at 25°C under a fixed angle of 90° in disposable polystyrene cuvettes. The measurements were recorded using a He–Ne laser of 633 nm. Zeta potential distribution of the nanoparticles was analyzed by Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy were obtained on a Bruker Vector 22 spectrophotometer in the range of 4000–500 cm−1 using the standard KBr disk method (sample/KBr = 1/100) (Bruker AXS, Inc., Billerica, MA, USA). Thermogravimetry (TG) and differential thermal analysis (DTA) were carried out on a Perkin-Elmer Pyris 1 TG/DTA instrument with a heating rate of 10°C/minute in flowing air (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Transmission electron micrographs were taken using a JEOL 1230 transmission electron microscope (TEM) (JOEL, Tokyo, Japan). Ultraviolet-visible (UV-VIS) absorption spectra were measured on a Cary 50 spectrophotometer (Varian, VIC, Australia).

Evaluation of the buffer effect

The buffer effect of VP16-LDH was evaluated by monitoring the pH changes in each suspension with the addition of 1 M HCl aqueous solution. A typical experiment was performed using a 100 mg sample in 10 mL of deionized distilled water. The flask was stirred continuously at 37°C. Aqueous HCl solution was subsequently added to each suspension until pH stabilized at an approximate value of 1.

In vitro VP16 release test from VP16-LDH

To determine the amount of VP16 loaded into the LDH, a standard weight of the nanohybrids and 5 mL of 1 M HCl were placed in a 10 mL flask. The solution was stirred until LDH layers were completely dissolved and subsequently analyzed with a UV-VIS spectrophotometer against a series of standards prepared using the same method; the concentration of VP16 was determined by monitoring the absorbance at 285 nm and calculated according to an obtained standard curve of VP16 (A = 0.0113C + 0.0008, r = 0.9988). The drug loading was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

The VP16 release test was performed in phosphate buffered saline solutions (0.02 M) of pH 7.4 and 4.6 containing 0.02 g of VP16-LDH while gently shaking at a constant temperature of 37°C. Aliquots (2 mL) were withdrawn at desired time intervals and filtered through a 0.45 μm syringe filter. The accumulated amount of VP16 released was determined by UV absorption at 285 nm. Four dissolution–diffusion kinetic models were used to fit the in vitro VP16-LDH release profiles.36–40

The zero-order model:

| (2) |

The first-order model:

| (3) |

The parabolic diffusion model:

| (4) |

The modified Freundlich model:

| (5) |

The zero-and first-order models are normally used to describe dissolution phenomena. The parabolic diffusion model expresses the diffusion controlled-release process. The modified Freundlich model explains diffusion behavior via ion exchange. In these equations, M0 and Mt are the amount of VP16 in the LDH hybrids at release time 0 and t, respectively, and k is the corresponding release rate constant.40

In vitro cytotoxicity and antitumor effect of VP16-LDH

Human gastric epithelial cell line (GES-1) and human gastric cancer cell lines (MKN45 and SGC-7901) were used in this study. Cells were routinely cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere in the flasks containing 10 mL of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. At 80%–90% confluence, cells were disassociated using trypsin–EDTA (Ethylene Diamine Tetraacetic Acid) and plated at a density of approximate 2 × 104 cells per well in a 96-well plate. The number of viable cells was determined by MTT assay with 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide. After incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humid atmosphere for 24 hours, triplicate wells were treated with VP16, VP16-LDH, and LDH of various concentrations (5 μg/mL, 10 μg/mL, 20 μg/mL, and 40 μg/mL), and incubation was continued as indicated above for 4 hours. For the LDH-treated wells, the amount of LDH was adjusted to be equal to that of VP16-LDH-treated wells. Subsequently, each well was incubated with 20 μL (5 mg/mL) of MTT dye solution for 4 hours at 37°C. After removal of the MTT solution, cells were treated with 150 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide, and the optical density absorbance at 490 nm was quantified using a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments Inc, Winooski, VT, USA). Cell viability was calculated by means of the following formula:

| (6) |

Results and discussion

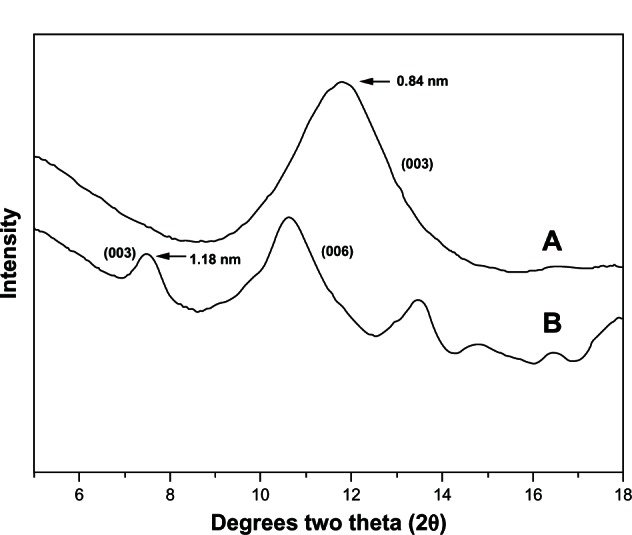

XRD analysis

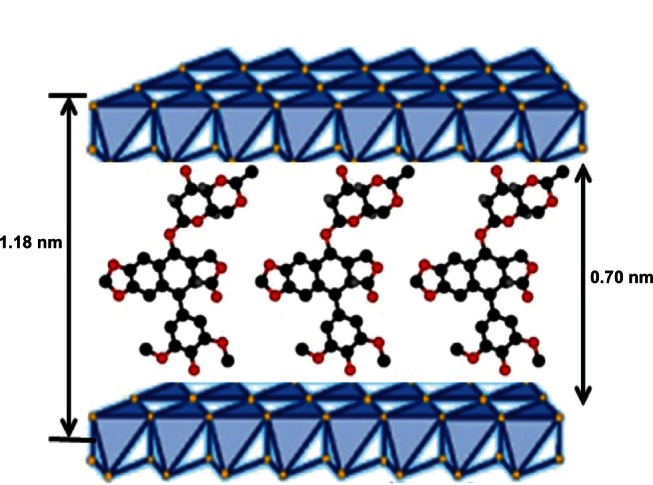

XRD patterns of LDH and the VP16-LDH nanohybrid are shown in Figure 2, and the basal spacing calculated from the XRD patterns is shown in Table 1. As shown in Figure 2, pristine LDH showed a typical XRD pattern for LDH-NO3 with basal spacing of 0.84 nm. Intercalation of drugs led to a significant increase in the interlayer space. As shown in Figure 2B, the reflection peaks in the pattern for VP16-LDH shift to lower angles and become weaker. This suggested that the successful intercalation of VP16 anions increased the basal spacing from 0.84–1.18 nm. Assuming a thickness of 0.48 nm for the brucite-like layer of LDH,41 the gallery height in VP16-LDH became 0.70 nm, which is shorter than the molecular length of VP16 (≈1.34 nm). As shown in Figure 3, based on the calculated gallery height, it can be deduced that the VP16 molecules were arranged in a tilted longitudinal monolayer, with tilting angles of approximately 58°. As shown in Table 1, the amount of VP16 intercalated into the LDH was calculated using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer and its drug loading was about 21.94% (w/w).

Figure 2.

X-ray powder diffraction patterns for Mg/Al-LDH and VP16-LDH. (A) X-ray powder diffraction pattern for Mg/Al-LDH. (B) X-ray powder diffraction pattern for VP16-LDH.

Abbreviations: Mg/Al-LDH, magnesium-aluminum layered double hydroxides; LDH, layered double hydroxide; VP16, etoposide.

Table 1.

The d-values of nanohybrid and VP16 loading

| Nanohybrid | d-values, nm

|

Gallery height, nm | VP16 loading, % (w/w) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d003 | d006 | d009 | |||

| LDH-NO3 | 0.84 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 0.48 | – |

| VP16-LDH | 1.18 | 0.83 | 0.66 | 0.70 | 21.94 |

Abbreviations: d, distance of layer; VP16, etoposide; LDH, layered double hydroxide.

Figure 3.

Schematic model of monolayer packing of VP16 drug molecules in the LDH interlayer space.

Abbreviations: VP16, etoposide; LDH, layered double hydroxide.

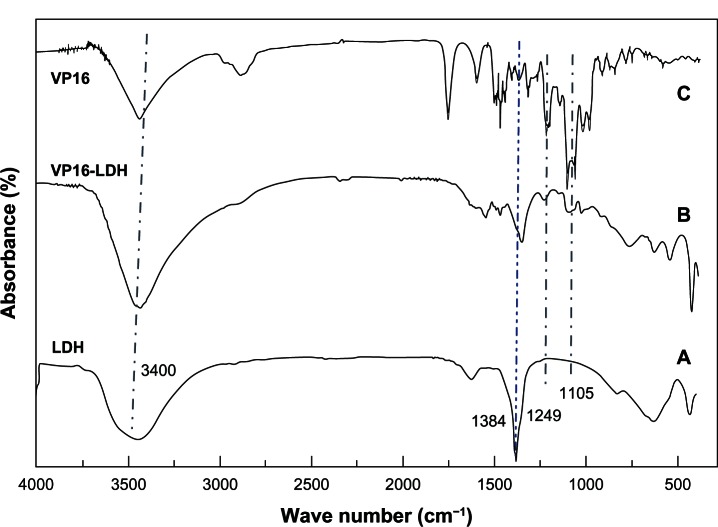

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and thermal stability analysis

The intercalation of VP16 into LDH interlayers was also suggested by infrared spectroscopy. As shown in Figure 4A, the pristine LDH-NO3 spectrum contained some peaks that commonly appear in magnesium-aluminum layered double hydroxides spectra.18,42 The broad absorption band around 3400 cm−1 was due to the stretching of O-H groups of both the hydroxide layer and interlayer water. The strong absorption band at 1384 cm−1 was due to stretching vibration of NO3−. In the low-frequency region, the bands at 809, 601, and 436 cm−1 were ascribed to the lattice vibration modes, specifically to M-O and O-M-O vibrations. As shown in Figure 4B and C, in the infrared spectrum of VP16 and VP16-LDH, the characteristic peaks around the absorption bands at 1486 cm−1 were due to the stretching vibrations of C=C in the backbone of the aromatic phenyl ring. Moreover, other VP16 absorption bands at 1249 and 1105 cm−1 observed in VP16-LDH were due to C–H vibration. Anionic exchange reaction resulted in the NO3− band at 1384 cm−1 becoming weaker, confirming that the interlayer NO3− ions were partly replaced by VP16 molecules. Therefore, it was clear that VP16 successfully intercalated into LDH.

Figure 4.

The FT-IR spectra for VP16, VP16-LDH, and Mg/Al-LDH. (A) FT-IR spectra for VP16. (B) FT-IR spectra for VP16-LDH. (C) FT-IR spectra for Mg/Al-LDH.

Abbreviations: VP16, etoposide; LDH, layered double hydroxide; Mg/Al-LDH, magnesium-aluminum layered double hydroxides; FT-IR, Fourier transform infrared.

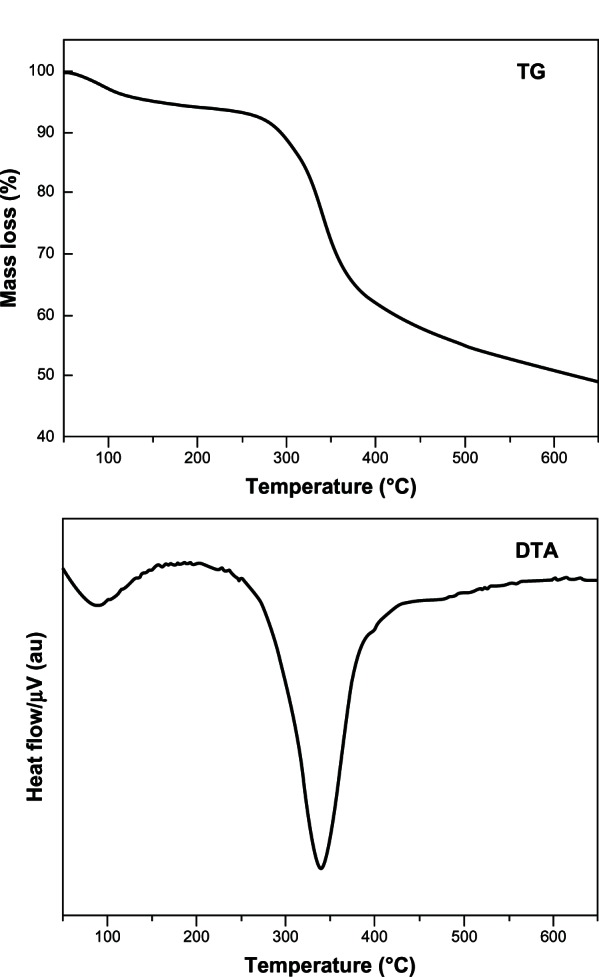

The TG/DTA curves of VP16-LDH nanohybrids are depicted in Figure 5. The sample shows two noticeable weight loss stages. The first stage occurred at approximately 100°C–200°C due to the removal of absorbed water molecules and interlayer crystal water, overlapping with trace dehydroxylation of the LDH layer. The following mass loss at around 300°C–400°C is attributed to dehydroxylation of the hydroxide layer and thermal degradation of intercalated VP16 molecules. The temperature was higher than the decomposition temperature of VP16, which demonstrated that the thermal stability of intercalated VP16 molecule was enhanced. Furthermore, the major weight loss of VP16-LDH in temperatures ranging from 300°C–400°C was approximately 24.01%, which is similar to the loading amount of VP16 measured by UV-VIS spectroscopy.26,27

Figure 5.

TG/DTA curves of VP16-LDH.

Abbreviations: au, arbitrary unit; TG, thermogravimetry; DTA, differential thermal analysis; VP16, etoposide; LDH, layered double hydroxide.

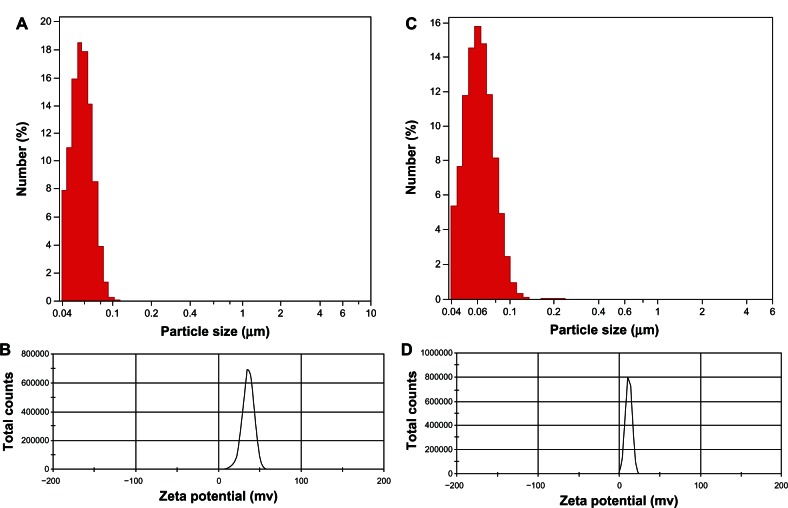

Particle size distribution and TEM examination

The particle size and distribution dynamics of VP16-LDH were investigated by photon correlation spectroscopy. The nanoparticles of LDH and VP16-LDH were narrowly distributed with a nominal hydrodynamic diameter of 57.4 nm (Figure 6A) and 62.5 nm (Figure 6C), respectively; the zeta potentials were 35.3 mV (Figure 6B) and 20.5 mV (Figure 6D), respectively.

Figure 6.

Particle size distribution and zeta potential distribution of LDH and VP16-LDH nanoparticles. (A and B) Particle size distribution and zeta potential distribution of LDH and (C and D) VP16-LDH nanoparticles.

Abbreviations: VP16, etoposide; LDH, layered double hydroxide.

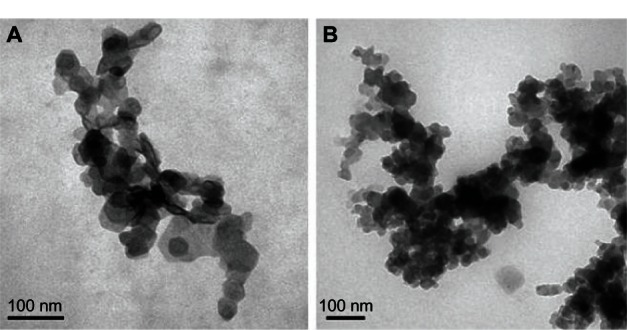

TEM samples were prepared by adding 300 mL of LDH slurry to 15 mL of deionized water followed by probe sonication of the solution for 2 minutes. A drop of the solution was then placed on a holey carbon copper grid and air dried. As shown in Figure 7, magnesium-aluminum layered double hydroxides were observed as compact, nonporous crystallites with a hexagonal platelike shape and a diameter of approximately 50 nm. When the VP16 intercalated into the inorganic host, the shape of the nanohybrid changed from regular hexagon to ellipse, and the crystal size increased, which was in accordance with the results of photon correlation spectroscopy.

Figure 7.

TEM images of nanohybrids. (A) Mg/Al-LDH crystals. (B) VP16-LDH nanohybrid crystals.

Abbreviations: TEM, transmission electron microscope; Mg/Al-LDH, magnesium-aluminum layered double hydroxides; LDH, layered double hydroxide; VP16, etoposide.

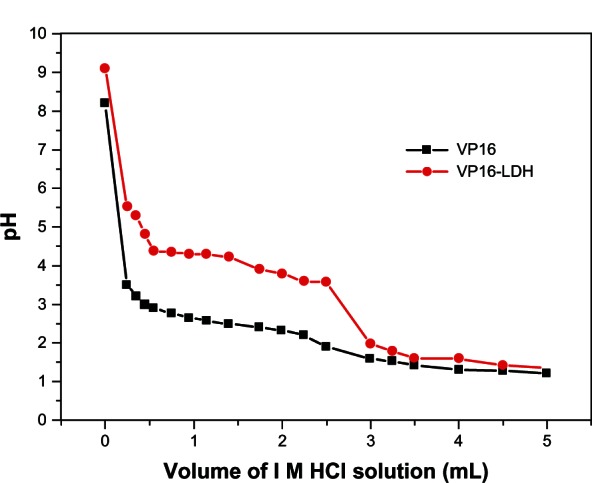

Buffer effect of VP16-LDH

Gastric fluids were mimicked to study the buffer effect of VP16-LDH nanohybrids by monitoring the changes in pH values with the addition of 1 M HCl.43Figure 8 depicts the corresponding graphs of pH value versus the volume of aqueous HCl solution added to the nanohybrid suspensions. As shown in Figure 8, the pH response of VP16 did not support a buffering property when pH value changed. However, VP16-LDH exhibited major buffering capacity when pH value was around 4. The neutralizing and buffering capabilities of VP16-LDH nanohybrids may come from the hydroxyl groups in its layers, and this function verifies LDH’s effective role of antacid, which is also described in our previous study.26,27,44 A three-phase release process can be observed. At the first stage with additive of HCl, the exfoliation of LDH particles was made by HCl to induce the integrity of the coating layer destroyed, which resulted in sharp decrement of solution pH from about 9.5–5.5. At the second stage, the pH of medium solution kept around 4, which was dependent on the neutralizing and buffering capabilities of VP16-LDH. At the last stage, the pH of medium solution was cut down and got to be 1 as the LDH nanoparticles were consumed by HCl. It may serve as an indicator that the LDH has begun dissolving; releasing VP16 through the removal of inorganic hosts under acidic conditions.45 Thus, LDH may be an ideal antacid to prompt available VP16 diffusion in simulated gastric fluid.

Figure 8.

Titration curves of VP16-LDH.

Note: V represents the added volume of 1 mol/L HCl aqueous solution.

Abbreviations: VP16, etoposide; LDH, layered double hydroxide.

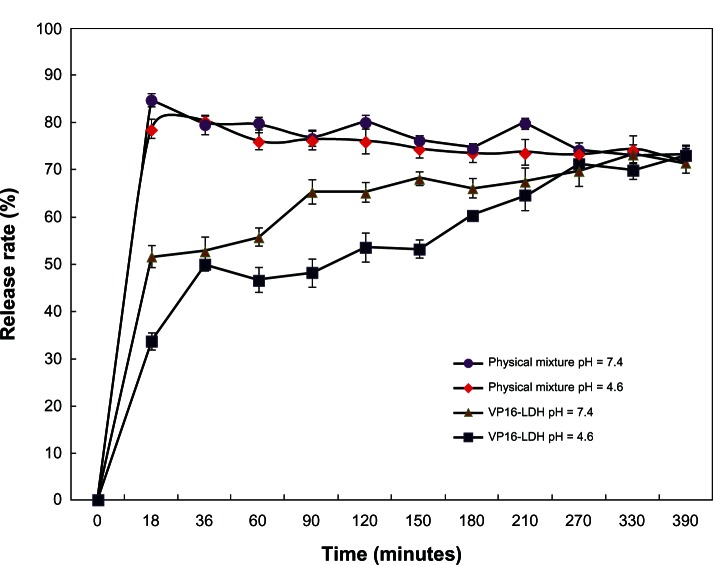

In vitro drug release of VP16-LDH

The release properties of the VP16 from VP16-LDH were investigated by adding the intercalated compound to a sample of simulated gastrointestinal (pH 4.6) and blood fluids (pH 7.4). Figure 9 shows the release profiles of VP16-LDH nanohybrids and physically mixed powder (VP16 and LDH) in solutions at pH 4.6 and 7.4. VP16 released from VP16-LDH nanohybrids at pH 4.6 and 7.4 showed a burst release during the first 20 minutes, which can be attributed to the release of the VP16 that adsorbed onto the surface of LDH particles. Subsequently, a slower release behavior was observed, which may be due to an ion-exchange process between the intercalated anions in the interlayer and phosphate anions in the buffer.46 At pH 7.4, the release of VP16-LDH was persistent and gradual, with released percentages of 51%, 74%, and 79% after 20, 150, and 390 minutes, respectively. As for the physical mixtures of VP16 and LDH, the release rate reached 85% immediately after 20 minutes, due to weak electrostatic interaction between VP16 molecules and the LDH surface. Thereafter, a slow decline of VP16 was observed with about 80% VP16 left in solution after 390 minutes, which may be attributed to the intercalation of VP16 into LDH. Such intercalation has been previously reported while observing the release of other drugs from a physical mixture.32 Therefore, it can be concluded that VP16-LDH shows an obvious sustained release profile. This nanomaterial could help increase the practical delivery of VP16.

Figure 9.

The in vitro release profiles of VP16 from VP16-LDH and physical mixture in buffer solutions at different pH values.

Abbreviations: VP16, etoposide; LDH, layered double hydroxide.

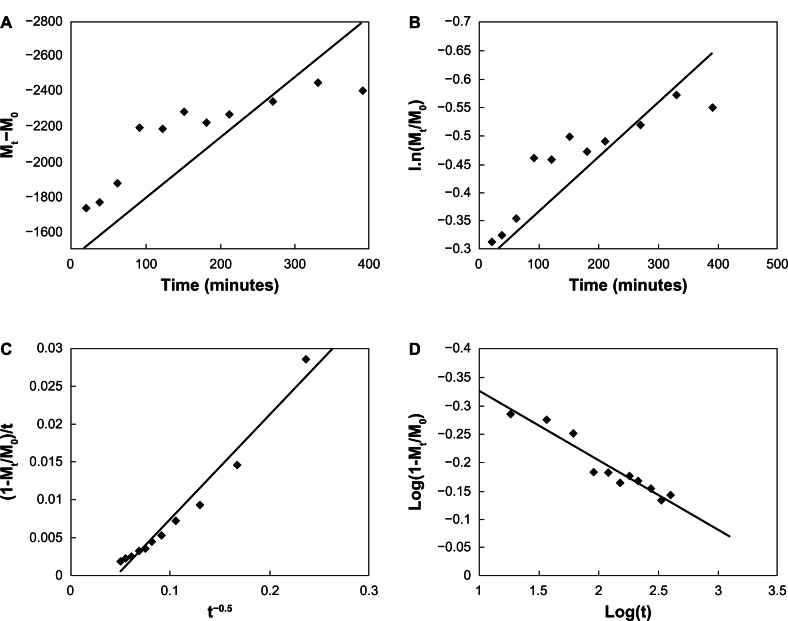

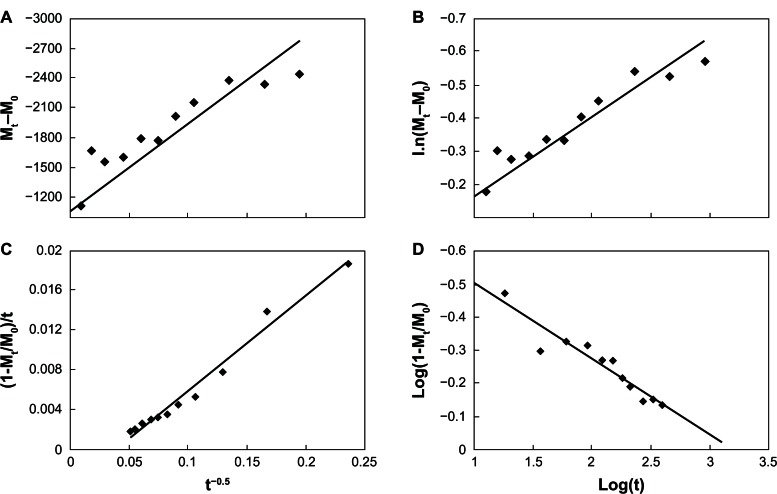

Four types of dissolution–diffusion kinetic models (zero-order, first-order, parabolic diffusion, and modified Freundlich model) were used in an attempt to explain the mechanism of release. The corresponding linear correlation coefficients (R2) were calculated (Table 2). At pH 7.4, the zero- and first-order models were not suitable to explain the whole release pattern of VP16-LDH, as evidenced by their small linear correlation coefficients with R2 = 0.4225 and 0.5931 (Figure 10). The release of VP16-LDH followed the other two models much better, with R2 = 0.9697 and 0.9230 for the parabolic diffusion and modified Freundlich models, respectively. The parabolic diffusion model describes intraparticle diffusion or surface diffusion, whereas the modified Freundlich model describes heterogeneous diffusion from flat surfaces via ion exchange. Thus, the drug release may be a coeffect, and a possible mechanism for VP16 release involves both intraparticle diffusion and surface diffusion, with either one being the main contributor.44 At pH 4.6 (Figure 11), the zero- and first-order models were also not suitable for the release pattern with the R2 = 0.6624 and 0.8345; however, the parabolic diffusion model was the best fit model for the release of VP16 (R2 = 0.98). This suggests that the release from VP16-LDH is controlled by the diffusion of VP16 anions from inside to the surface of the LDH particles.

Table 2.

Rate constants and correlation coefficients of the dissolution–diffusion kinetic models applied to VP16 release from VP16-LDH

| Kinetic model | Kinetic equation | R2 (pH = 7.4) | R2 (pH = 4.6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-order | Mt – M0 = kt + a | 0.4225 | 0.6624 |

| First-order | Ln (Mt/M0) = −kt + a | 0.5931 | 0.8345 |

| Parabolic diffusion model | (1 – Mt/M0)/t) = kt−0.5 + a | 0.9697 | 0.9783 |

| Modified Freundlich model | 1 – Mt/M0 = kta | 0.9230 | 0.8977 |

Abbreviations: VP16, etoposide; LDH, layered double hydroxide.

Figure 10.

Fitting the VP16-LDH release data at ph 7.4 to different kinetic equations. (A) Zero-order, (B) first-order, (C) parabolic diffusion model, and (D) modified Freundlich model.

Abbreviations: VP16, etoposide; LDH, layered double hydroxide; t, time.

Figure 11.

Fitting the VP16-LDH release data at pH 4.6 to different kinetic equations. (A) Zero-order, (B) first-order, (C) parabolic diffusion model, and (D) modified Freundlich model.

Abbreviations: VP16, etoposide; LDH, layered double hydroxide; t, time.

In vitro cytotoxicity and antitumor effect of VP16-LDH

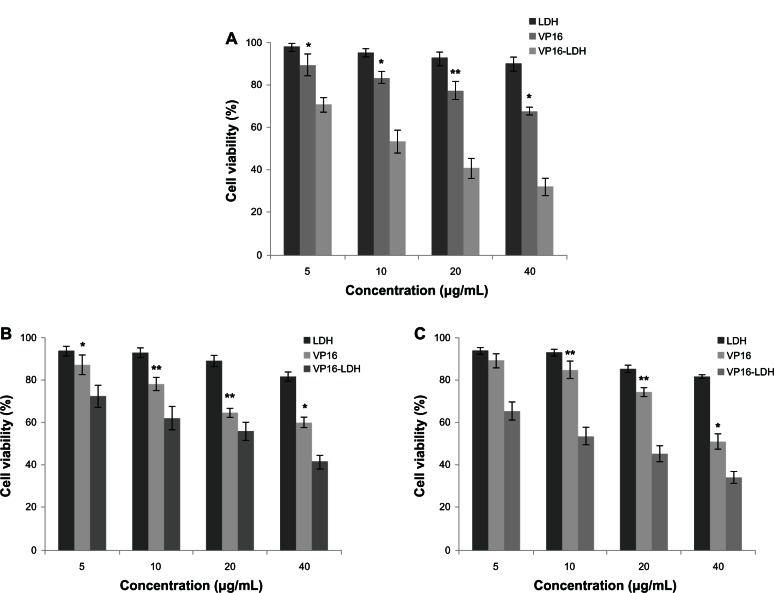

Figure 12A shows the effect of VP16, LDH, and VP16-LDH on the proliferation of GES-1 cells at various VP16 concentrations. The cytotoxicity of VP16 and VP16-LDH to GES-1 cells increased with increasing dose of VP16, whereas pristine LDH had no significant cytotoxic effect. VP16-LDH has no obvious toxicity to GES-1 cells compared with free VP16 of the same concentration. Thus, LDH, as carriers of VP16, can effectively reduce the cytotoxicity of VP16 to normal cells.

Figure 12.

The effect of LDH, VP16, and VP16-LDH of different VP16 concentrations on GES-1 cells and MKN45 and SGC-7901 tumor cells after 48 hours of incubation. (A) Cytotoxicity of LDH, VP16, and VP16-LDH of different VP16 concentrations to GES-1 cells after 48 hours. The effect of LDH, VP16, and VP16-LDH of different VP16 concentrations on the growth of MKN45 (B) and SGC-7901 (C) tumor cells after 48 hours.

Notes: Results represent the means of three independent experiments, and error bars represent the standard error of the mean. N = 3; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001.

Abbreviations: LDH, layered double hydroxide; VP16, etoposide.

As shown in Figure 12B and C, VP16 and VP16-LDH suppressed the proliferation of tumor cells MKN45 and SGC-7901, whereas LDH by itself exerted no significant effect. Moreover, VP16-LDH had higher tumor suppression efficiency than VP16 alone at various concentrations. These results indicate that VP16-LDH may be more effective in cancer treatment than VP16 alone. This may be because VP16 in the hybrid system can reach tumor cell membranes before decomposing, because the VP16 molecules are stabilized when they are entrapped in LDH. Additionally, Choy et al47 reported that the use of LDH nanoparticles as delivery vectors can improve the cellular uptake of biomolecules. When LDH-drug particles are adhered to the cell membrane surface, some are internalized into the cell. The possible pathway for such nanohybrids to be internalized into cells is phagocytosis or endocytosis.11 Some studies have shown that particles with diameters less than 200 nm are small enough to avoid nonselective uptake by macrophages of the reticuloendothelial system, and are more effective when they accumulate at the tumor site via the enhanced permeability and retention effect upon circulation in the blood vessels,48–50 because tumor vessels are often dilated and fenestrated with an average pore size of less than 1 μm compared with normal tissue due to rapid formation of vessels that must serve the fast-growing tumor,51 while normal tissues contain capillaries with tight junctions that are less permeable to nanosized particles. Therefore, VP16-LDH nanohybrids may be readily taken up by tumor cells and could thus permeate the tumor cell membrane much more effectively.41,52 These results suggest that LDH can be used as an excellent inorganic carrier for an advanced biocompatible drug delivery system, and VP16-LDH is a potential antitumor drug for a broad range of gastric cancer therapeutic applications. The in vivo delivery of VP16-LDH in an animal model will be performed in the future study.

Conclusion

We successfully synthesized and characterized drug– inorganic nanohybrids, specifically constructs consisting of LDHs intercalated with VP16. The prepared nanoparticles contained an average diameter of 62.5 nm with a zeta potential of 20.5 mV. Evaluation of the buffering effect of VP16-LDH indicated that VP16-LDH possessed a good buffer effect in low pH media. The loading amount of intercalated VP16 was 21.94% and showed a profile of sustained release making a promising candidate for controlled drug release applications. The cytotoxicity and antitumor tests showed that VP16-LDH nanoparticles exhibited low toxicity to normal GES-1 cells and better antitumor efficacy on MKN45 and SGC-7901 cells. In summary, LDH may be an excellent inorganic carrier of VP16, and VP16-LDH shows great potential as an antitumor therapy. The promising results encourage us to perform further in vivo delivery in an animal model in the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 31100855 and 31140038), a Special Financial Grant from the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant 2012T50440), the Program for Young Excellent Talents in Tongji University (Grant 2000219054), and the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (Grant 11411951500).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Drewinko B, Barlogie B. Survival and cycle-progression delay of human lymphoma cells in vitro exposed to VP-16-213. Cancer Treat Rep. 1976;60(9):1295–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hainsworth JD, Greco FA. Etoposide: twenty years later. Ann Oncol. 1995;6(4):325–341. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a059180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slevin ML. Low-dose oral etoposide: a new role for an old drug? J Clin Oncol. 1990;8(10):1607–1609. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.10.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowis SP, Newell DR. Etoposide for the treatment of paediatric tumours: what is the best way to give it? Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A(13):2291–2297. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00301-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.You B, Tranchand B, Girard P, et al. Etoposide pharmacokinetics and survival in patients with small cell lung cancer: a multicentre study. Lung Cancer. 2008;62(2):261–272. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Maanen JM, Retèl J, de Vries J, Pinedo HM. Mechanism of action of antitumor drug etoposide: a review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988;80(19):1526–1533. doi: 10.1093/jnci/80.19.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah JC, Chen JR, Chow D. Preformulation study of etoposide: identification of physicochemical characteristics responsible for the low and erratic oral bioavailability of etoposide. Pharm Res. 1989;6(5):408–412. doi: 10.1023/a:1015935532725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hainsworth JD, Williams SD, Einhorn LH, Birch R, Greco FA. Successful treatment of resistant germinal neoplasms with VP-16 and cisplatin: results of a Southeastern Cancer Study Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 1985;3(5):666–671. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1985.3.5.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seida Y, Nakano Y. Removal of phosphate by layered double hydroxides containing iron. Water Res. 2002;36(5):1306–1312. doi: 10.1016/s0043-1354(01)00340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwon SJ, Choy JH. A novel hybrid of Bi-based high-Tc superconductor and molecular complex. Inorg Chem. 2003;42(25):8134–8136. doi: 10.1021/ic034755t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu ZP, Lu GQ. Layered double hydroxide nanomaterials as potential cellular drug delivery agents. Pure Appl Chem. 2006;78(9):1771–1779. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu ZP, Zeng QH, Lu GQ, Yu AB. Inorganic nanoparticles as carriers for efficient cellular delivery. Chem Eng Sci. 2006;61(3):1027–1040. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choy JH, Kim YI, Kim BW, Campet G, Portier J, Huong PV. Grafting mechanism of electrochromic PAA-WO3 composite film. J Solid State Chem. 1999;142(2):368–373. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choy JH, Yoon JB, Park JH. In situ XAFS study at the Zr K-edge for SiO2/ZrO2 nano-sol. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2001;8(Pt 2):782–784. doi: 10.1107/s090904950001606x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwak SY, Kriven WM, Wallig MA, Choy JH. Inorganic delivery vector for intravenous injection. Biomaterials. 2004;25(28):5995–6001. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofer C, Teichert C, Wächter M, Bobek T, Lyutovich K, Kasper E. Nanostructure formation on ion-eroded SiGe film surfaces. Superlattices and Microstructures. 2004;36(1–3):281–291. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li A, Qin LL, Wang SL, et al. The use of layered double hydroxides as DNA vaccine delivery vector for enhancement of anti-melanoma immune response. Biomaterials. 2011;32(2):469–477. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aisawa S, Takahashi S, Ogasawara W, Umetsu Y, Narita E. Direct intercalation of amino acids into layered double hydroxides by coprecipitation. J Solid State Chem. 2001;162(1):52–62. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang H, Qi R, Evans DG, Duan X. Synthesis and characterization of a novel nano-scale magnetic solid base catalyst involving a layered double hydroxide supported on a ferrite core. J Solid State Chem. 2004;177(3):772–780. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hibino T, Nishiyama T. Role of TGF-beta2 in the human hair cycle. J Dermatol Sci. 2004;35(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong KK, Colfen H, Whilton NT, Douglas T, Mann S. Synthesis and characterization of hydrophobic ferritin proteins. J Inorg Biochem. 1999;76(3–4):187–195. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(99)00114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakayama H, Hayashi A, Eguchi T, Nakamura N, Tsuhako M. Adsorption of formaldehyde by polyamine-intercalated α-zirconium phosphate. Solid State Sciences. 2002;4(8):1067–1070. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang G, Feng L, Luck RL, Evans DG, Wang Z, Duan X. Sol-gel synthesis, characterization and catalytic property of silicas modified with oxomolybdenum complexes. J Mol Catal A Chem. 2005;241(1–2):8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang H, Zou K, Sun H, Duan X. A magnetic organic–inorganic composite: synthesis and characterization of magnetic 5-aminosalicylic acid intercalated layered double hydroxides. J Solid State Chem. 2005;178(11):3485–3493. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H, Zou K, Guo S, Duan X. Nanostructural drug-inorganic clay composites: structure, thermal property and in vitro release of captopril-intercalated Mg-Al-layered double hydroxides. J Solid State Chem. 2006;179(6):1792–1801. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao R, Wang WR, Pan L, et al. A sustained folic acid release system based on ternary magnesium/zinc/aluminum layered double hydroxides. J Mater Sci. 2011;46(8):2635–2643. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qin LL, Wang SL, Zhang R, Zhu RG, Sun XY, Yao S. Two different approaches to synthesizing Mg-Al-layered double hydroxides as folic acid carriers. J Phys Chem Solids. 2008;69(11):2779–2784. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qin L, Xue M, Wang W, et al. The in vitro and in vivo anti-tumor effect of layered double hydroxides nanoparticles as delivery for podophyl-lotoxin. Int J Pharm. 2010;388(1–2):223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li B, He J, Evans DG, Duan X. Enteric-coated layered double hydroxides as a controlled release drug delivery system. Int J Pharm. 2004;287(1–2):89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi SJ, Choy JH. Layered double hydroxide nanoparticles as target-specific delivery carriers: uptake mechanism and toxicity. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2011;6(5):803–814. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ambrogi V, Famiani F, Perioli L, Marmottini, Di Cunzolo I, Rossi C. Effect of MCM-41 on the dissolution rate of the poorly soluble plant growth regulator, the indole-3-butyric acid. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials. 2006;96(1–3):177–183. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gu Z, Thomas AC, Xu ZP, Campbell JH, Lu GQ. In vitro sustained release of LMWH from MgAl-layered double hydroxide nanohybrids. Chem Mater. 2008;20(11):3715–3722. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tyner KM, Schiffman SR, Giannelis EP. Nanobiohybrids as delivery vehicles for camptothecin. J Control Release. 2004;95(3):501–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2003.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xue YH, Zhang R, Sun XY, Wang SL. The construction and characterization of layered double hydroxides as delivery vehicles for podophyllotoxins. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2008;19(3):1197–1202. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-3221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu ZP, Walker TL, Liu KL, Cooper HM, Lu GQ, Bartlett PF. Layered double hydroxide nanoparticles as cellular delivery vectors of supercoiled plasmid DNA. Int J Nanomedicine. 2007;2(2):163–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li ZH. Sorption kinetics of hexadecyltrimethylammonium on natural clinoptilolite. Langmuir. 1999;15(19):6438–6445. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang JH, Han YS, Park M, et al. New inorganic-based drug delivery system of indole-3-acetic acid-layered metal hydroxide nanohybrids with controlled release rate. Chem Mater. 2007;19(10):2679–2685. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demirbas E, Kobya M, Senturk E, Ozkan T. Adsorption kinetics for the removal of Cr (VI) from aqueous solutions on the activated carbons prepared from agricultural wastes. Water South Africa. 2004;30:533–539. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kodama T, Harada Y, Ueda M, Shimizu KI, Shuto K, Komarneni S. Selective exchange and fixation of strontium ions with ultrafine Na-4-mica. Langmuir. 2001;17(16):4881–4886. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sparks DL. Kinetics of Soil Chemical Processes. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Publishers; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choy JH, Jung JS, Oh JM, et al. Layered double hydroxide as an efficient drug reservoir for folate derivatives. Biomaterials. 2004;25(15):3059–3064. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kloprogge JT, Wharton D, Hickey L, Frost RL. Infrared and Roman study of interlayer anions CO32−, NO3−, SO42− and ClO4−in Mg/Al-hydrotalcite. American Mineralogist. 2000;87:623–629. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tronto J, Crepaldi EL, Pavan PC, De Paula CC, Valim JB. Organic anions of pharmaceutical interest intercalated in magnesium aluminum LDHs by two different methods. Molecular Crystals Liquid Crystals. 2001;356(1):227–237. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qian WY, Sun DM, Zhu RR, Du XL, Liu H, Wang SL. pH-sensitive strontium carbonate nanoparticles as new anticancer vehicles for controlled etoposide release. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:5781–5792. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S34773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.bin Hussein MZ, Zainal Z, Yahaya AH, Foo DW. Controlled release of a plant growth regulator, alpha-naphthaleneacetate from the lamella of Zn-Al-layered double hydroxide nanocomposite. J Control Release. 2002;82(2–3):417–427. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pan DK, Zhang H, Zhang T, Duan X. A novel organic-inorganic microhybrids containing anticancer agent doxifluridine and layered double hydroxides: Structure and controlled release properties. Chem Eng Sci. 2010;65(12):3762–3771. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choy JH, Kwak SY, Park JS, Jeong YJ. Cellular uptake behavior of [γ-32P] labeled ATP-LDH nanohybrids. J Mater Chem. 2001;11(6):1671–1674. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oh JM, Choi SJ, Lee GE, Kim JE, Choy JH. Inorganic metal hydroxide nanoparticles for targeted cellular uptake through clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Chem Asian J. 2009;4(1):67–73. doi: 10.1002/asia.200800290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, Farokhzad OC, Margalit R, Langer R. Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2(12):751–760. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maeda H. The enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect in tumor vasculature: the key role of tumor-selective macromolecular drug targeting. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2001;41:189–207. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(00)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fahmy TM, Fong PM, Goyal A, Saltzman WM. Targeted nanoparticles for drug delivery. Materials Today. 2005;8(8 Suppl 1):18–26. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuan H, Miao J, Du YZ, You J, Hu FQ, Zeng S. Cellular uptake of solid lipid nanoparticles and cytotoxicity of encapsulated paclitaxel in A549 cancer cells. Int J Pharm. 2008;348(1–2):137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]