Abstract

Objectives

To assess the impact of reduced frequency of oral therapies from multiple-dosing schedules to a once-daily (OD) dosing schedule on adherence, compliance, persistence, and associated economic impact.

Methods

A meta-analysis was performed based on relevant articles identified from a comprehensive literature review using MEDLINE® and Embase®. The review included studies assessing adherence with OD, twice-daily (BID), thrice-daily (TID), and four-times daily (QID) dosing schedules and costs associated with optimal/suboptimal adherence among patients with acute and chronic diseases. Effect estimates across studies were pooled and analyzed using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effect model.

Results

Forty-three studies met inclusion criteria, and meta-analyzable data were available from 13 studies. The overall results indicated that OD schedules were associated with higher adherence rates (odds ratio [OR] 3.07, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.80–5.23; P < 0.001 for OD versus > OD dosing) and compliance rates (OR 3.50, 95% CI 1.73–7.08; P < 0.001 for OD versus > OD dosing); persistence rates showed the same direction but were not statistically significant (OR 1.43, 95% CI 0.62–3.29; P = 0.405 for OD versus BID dosing). Results for each of the conditions were consistent with those observed overall with respect to showing the benefits of less frequent dosing. From a health economic perspective, higher adherence rates with OD relative to multiple dosing in a number of conditions were consistently associated with corresponding lower costs of health care resources utilization.

Conclusion

Current meta-analyses suggested that across acute and chronic disease states, reducing dosage frequency from multiple dosing to OD dosing may improve adherence to therapies among patients. Improving adherence may result in subsequent decreases in health care costs.

Keywords: compliance, dosage frequency, persistence, random-effect meta-analyses

Introduction

Worldwide public health efforts to address a variety of chronic conditions are being undermined by an alarmingly low adherence to therapies.1 Nonadherence is a serious problem in patients on long-term treatment, accounting for up to 50% of cases where drugs fall short of their therapeutic goals.2–4 For nonadherent patients, the benefits of extended duration of treatment may not be sufficiently apparent.2,3 Adherence problems are prevalent where self-administration of treatment is required, including acute and chronic illnesses such as hypertension,5 depression,6 diabetes,7 HIV/AIDS,8 transplant,9 and cardiovascular (CV) disorders.10

Nonadherence to treatment is a difficult issue to evaluate due to inconsistent definitions and measurement methodologies.11 Standard definitions of adherence, compliance, and persistence were developed by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Medication Compliance and Persistence Work Group.12 According to the group, medication compliance (synonym: adherence) refers to conforming to the recommendations made by a provider with respect to timing, dosing, and frequency of medication taking.12 Medication persistence refers to conforming to a recommendation of continuing treatment for the prescribed length of time.12 A wide variety of factors contribute to nonadherence,13,14 including drug regimen complexity as a major contributing factor.15

Until 2006, published reviews and meta-analyses focusing on adherence, compliance, and persistence demonstrated that decreasing the number of doses taken daily provides benefits in terms of medication-taking behaviour.15–19 These reviews and meta-analyses neither examined observational studies nor assessed the impact on associated costs.

To fill this gap, a comprehensive literature review and meta-analyses were conducted to assess the impact of multiple-daily dosing and once-daily (OD) dosing of oral therapies prescribed in acute and chronic diseases on adherence, compliance, persistence, and health care costs. The authors of the current study would also like to note that subsequent to our analyses and prior to submission for publication, a comprehensive and rigorous meta-analytic study was published that evaluated the relationship between dosing frequency and medication adherence in studies of patients with chronic diseases.20 That study, which provides a valuable update of the literature, confirmed the inverse relationship between medication adherence and dosing frequency, with once daily dosing shown to be associated with the greatest adherence. However, similar to other studies, there was no evaluation of the impact of dosing frequency on costs, and neither did that study stratify the analyses by disease states.

Materials and methods

The original objective was to compare adherence to OD dosing regimen with that of multiple-dosing regimens in patients with chronic pain but, because of the lack of published evidence in this disease area, the investigation was expanded by not including a term that would have limited the search to chronic pain. This comprehensive literature review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.21

Study eligibility criteria

This review included comparative studies published in English and assessed adherence/compliance/persistence with OD, twice-daily (BID), three-times daily (TID), or four-times daily (QID) dosing, including associated costs among patients with acute and chronic diseases. There was no restriction on the treatments assessed in the study other than that they were orally administered.

Data source and evidence synthesis

The search was conducted in MEDLINE® (including MEDLINE® In-Process) and Embase® up to September 16, 2011. All retrieved studies were screened, and only those meeting predefined eligibility criteria (Appendix) were included in the review.

Initial screening of the retrieved citations was conducted independently by two reviewers on the basis of the title and the abstract. Any discrepancy between the reviewers was reconciled by a third reviewer. The full-text publications of all citations of potential interest were then screened for inclusion by two independent reviewers, with all disagreements reconciled by a third reviewer. Relevant data from all included studies were extracted independently by two reviewers using a predefined extraction grid; any differences were then resolved by a third independent reviewer.

Extracted data included percentage of patients adherent and nonadherent to therapy, medication possession ratio (MPR), and odds ratio (OR) or risk ratio or β-coefficient to evaluate the association between adherence with different dosing schedules. Costs associated with optimal/suboptimal adherence and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were also extracted. The same type of extraction for adherence was performed for compliance and persistence. Due to variability in definitions of adherence/compliance/persistence across studies, no single definition criteria was used to define these parameters. The studies were classified as evaluating adherence/compliance/persistence based on author definitions in the associated studies for the purpose of quantitative analyses.

Statistical analysis

Random-effect meta-analyses using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model were conducted.22 Estimated ORs for the studies were combined using Stata® v11.1. For the purpose of analysis, data for all dosing schedules administered more than OD were pooled under > OD regimen group; P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The statistical heterogeneity within each analysis was assessed using the I2 statistic.23 Multivariate-adjusted effect estimates were included in the meta-analysis; however, when multivariate effect estimates were not available, unadjusted ORs were computed from the treatment distributions for those with and without the event of interest reported in the published articles. A linear meta-regression considering random-effect modeling was performed using Stata® v11.1 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) to explore the effect on adherence, compliance, or persistence with respect to different dosing schedules.24

Results

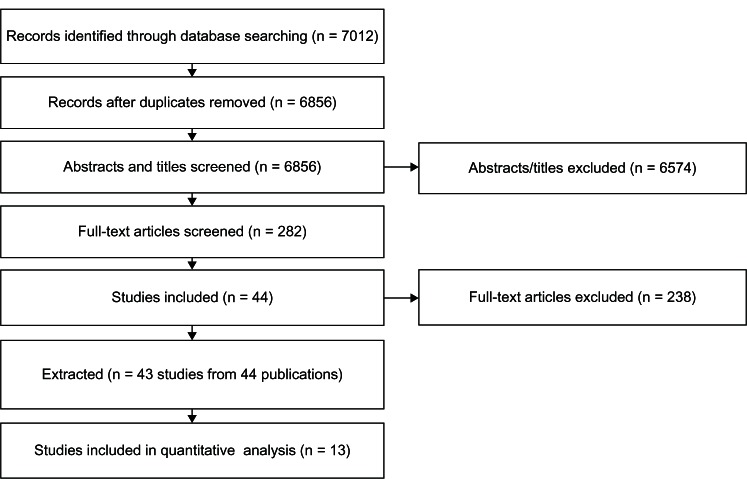

The search terms and strategy are shown in Table 1, and the schematic selection process of studies from the identified records is presented in Figure 1. Forty-three studies (44 publications) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and provided the basis for this review, encompassing a variety of acute and chronic conditions in addition to pain. The characteristics of these studies including the outcome evaluated (eg, adherence, compliance, and/or persistence) are summarized in Table 2. Of these 43 studies, 13 were amenable to conducting random-effect meta-analyses. Studies with non-meta-analyzable data were discussed descriptively.

Table 1.

Search terms and initial strategy for identifying relevant studies

| Search number | Search strings |

|---|---|

| 1 | (once OR twice OR thrice OR one OR two OR three) NEAR/1 (daily* OR per*day) OR ‘OD’:ab,ti OR ‘BID’:ab,ti OR ‘TID’:ab,ti OR ‘QID’:ab,ti |

| 2 | adhere*:ab,ti OR nonadhere*:ab,ti OR (non NEAR/1 adhere*):ab,ti OR complian*:ab,ti OR noncomplian*:ab,ti OR (non NEAR/1 complian*):ab,ti OR ‘medication possession’:ab,ti OR mpr:ab,ti OR ‘persistence’:ab,ti OR (non NEAR/1 persist*):ab,ti OR nonpersisten*:ab,ti OR ‘medication possession ratio’ OR ‘treatment refusal’ OR ‘medication compliance’/exp OR medication NEAR/1 complian* OR medication NEAR/1 persisten* OR medication NEAR/1 adhere* |

| 3 | patient NEAR/1 (monitoring OR care OR counselling) |

| 4 | #2 OR #3 |

| 5 | #1 AND #4 |

Figure 1.

Search terms and strategy for identifying relevant studies.

Table 2.

Summary of included studies for a dosage frequency comparison in medication treatments for chronic diseases

| Disease sub-type | Study | Intervention | Number of patients | Mean duration (range) of follow-up in weeks | Study country(ies) | Outcome assessed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | Cells43 | Isradipine RF: BID | 12 | 9.4 | NR | Compliance |

| Isradipine MR: OD | 12 | |||||

| Baird29 | Betaioc® Durules®: OD | 193 | NR | Canada and UK | Compliance | |

| Betaloc®: BID | 196 | |||||

| Maro34 | Antihypertensive: OD | 61 | 156 | Tanzania | Compliance* | |

| Antihypertensive: BID | 34 | |||||

| Antihypertensive: TID | 51 | |||||

| Turki40 | Antihypertensive: OD | 209 | NR | Malaysia | Adherence* | |

| Antihypertensive: BID | 148 | |||||

| Antihypertensive: ≥TID | 23 | |||||

| Girvin44 | Enalapril: OD | 25 | 16 | Ireland | Compliance | |

| Enalapril: BID | 25 | |||||

| Andrejak30 | Trandolapril: OD | 71 | 26 | France | Compliance* | |

| Captopril: BID | 62 | |||||

| Boissel45 | Nicardipine: TID | 3636 | 12 | France | Compliance | |

| Nicardipine SR: BID | 3638 | |||||

| Angina pectoris | Brown46,† | ISMN: OD | NR | NR | UK | Cost (total, direct, and indirect) |

| ISMN: BID | NR | |||||

| Kardas47 | Betaxolol: OD | 56 | 10 | Poland | Compliance* | |

| Metoprolol tartrate: BID | 56 | |||||

| Cardiovascular disorders | Bae49 | Cardiovascular regimen: BID | 1,077,936 | NR | NR | Adherence* |

| Cardiovascular regimen: OD | ||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | Song10 | Carvedolol: OD | 28,384 | NR | NR | Persistence* |

| Carvedolol: BID | ||||||

| Amlodipine: OD | ||||||

| Captopril: TID | ||||||

| Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) | Hess37 | Carvedilol at 6 months: OD | 168 | 52 | NR | Persistency, |

| Carvedilol at 6 months: BID | 2086 | MPR, compliance | ||||

| Metformin at 6 months: OD | 136 | |||||

| Metformin at 6 months: BID | 614 | |||||

| Carvedilol at 12 months: OD | 168 | |||||

| Carvedilol at 12 months: BID | 2086 | |||||

| Metformin at 12 months: OD | 136 | |||||

| Metformin at 12 months: BID | 614 | |||||

| Heart transplant | Doesch48 | Tacrolimus/Cyclosporin A: BID | 50 | 4 | NR | Adherence* |

| Tacrolimus: OD | 50 | |||||

| Depression | McLaughlin36 | Bupropion: OD | 756 | NR | USA | Persistence* |

| Bupropion: BID | 2382 | |||||

| Granger39 | Bupropion: OD | 142 | NR | NR | Adherence* | |

| Bupropion: BID | 349 | |||||

| Stang6 | Bupropion: TID | 31 | ||||

| Bupropion SR: BID | 12,468 | NR | USA | Persistence*, adherence, | ||

| Stang50 | Bupropion XL: OD | 257,049 | MPR | |||

| Bupropion SR: BID | 1917 | 39 | USA | Persistence*, MPR | ||

| Bupropion XL: OD | 1074 | |||||

| Schizophrenia | Pfeiffer52 | Antipsychotic medication: OD | 1381 | NR | USA | Adherence* |

| Antipsychotic medication: | 258 | |||||

| Multiple daily dosing | ||||||

| Epilepsy | Cramer51 | Antiepileptics: OD regimen | 3 | 14 | NR | Compliance* |

| Antiepileptics: BID regimen | 12 | |||||

| Antiepileptics: TID regimen | 7 | |||||

| Antiepileptics: QID regimen | 4 | |||||

| Pain | Carlos54,† | Duloxetine: OD | NR | 13 | Mexico | Cost-effectiveness* |

| Gabapentin: TID | NR | |||||

| Pregabalin: BID | NR | |||||

| Migraine | Mulleners53 | Propranolol: OD | 11 | NR | UK | Compliance |

| Atenolol: BID | 11 | |||||

| Pizotifen or methysergide: TID | 7 | |||||

| Type 2 Diabetes | Winkler27 | Sulfonylureas OD: adherence by pill count > 90% | 11 | 7.7 | Germany | Adherence* |

| Sulfonylureas OD: adherence by MEMS (dosage) > 90% | 11 | |||||

| Sulfonylureas OD: adherence by MEMS (regimen) > 90% | 11 | |||||

| Sulfonylureas OD: adherence by pill count 90%–110% | 11 | |||||

| Sulfonylureas OD: adherence by MEMS (dosage) 90%–110% | 11 | |||||

| Sulfonylureas OD: adherence by MEMS (regimen) 90%–110% | 11 | |||||

| Sulfonylureas BID/TID: adherence by pill count > 90% | 8 | |||||

| Sulfonylureas BID/TID: adherence by MEMS (dosage) > 90% | 8 | |||||

| Sulfonylureas BID/TID: adherence by MEMS (regimen) > 90% | 8 | |||||

| Sulfonylureas BID/TID: adherence by pill count 90%–110% | 8 | |||||

| Sulfonylureas BID/TID: adherence by MEMS (dosage) 90%–110% | 8 | |||||

| Sulfonylureas BID/TID: adherence by MEMS (regimen) 90%–110% | 8 | |||||

| Dezii7 | Glipizide GITS: OD | 746 | 51.3 | NR | Adherence index*, persistence* | |

| Glipizide: BID | 246 | |||||

| Kardas55 | Gliclazide MR: OD | 55 | 16 | Poland | Compliance* | |

| Glibenclamide: BID | 50 | |||||

| Pullar33 | Phenobarbital: BID | 59 | 4 | England | Compliance*, inadequate compliance, safety | |

| Phenobarbital: BID | 60 | |||||

| Phenobarbital: TID | 60 | |||||

| Charpentier56 | Glimepiride: OD | 100 | 26 (10-week dose titration and 16-week maintenance period) | France | Compliance* | |

| Glibenclamide: BID/TID | 101 | |||||

| HIV/AIDS | Carrieri8 | HAART: OD | 1110 | 260 | France | Non-adherence* |

| HAART: BID | ||||||

| HAART: ≥TID | ||||||

| Negredo25 | HAART: OD | 85 | 48 | NR | Adherence | |

| HAART: BID | 84 | |||||

| Stone57 | ART: ≤2 doses daily (self-reported) | 170 | NR | USA | Adherence | |

| ART: ≥3 doses daily (self reported) | 119 | |||||

| ART: ≤2 doses daily (correct) | 141 | |||||

| ART: ≥3 doses daily (correct) | 148 | |||||

| AbelIan58 | Ritonavir: BID | 45 | NR | Spain | Adherence* | |

| Indinavir: TID | 70 | |||||

| Saquinavir: TID | 49 | |||||

| Echarri Martinez35 | HAART: OD | 75 | 26 | Spain | Adherence* | |

| HAART: BID | 217 | |||||

| HAART: TID | 6 | |||||

| Moyle38 | ART: OD | 15 | NR | France, Germany, Italy, Spain,, UK | Adherence* | |

| ART: BID | 255 | |||||

| ART: TID | 109 | |||||

| ART: >TID | 58 | |||||

| Respiratorytract infections (RTI) | Kardas31 | Respiratory tract infection therapy: OD | 250 | 0.9 | Poland | Compliance* |

| Respiratory tract infection therapy: BID | 251 | |||||

| Kardas32 | Clarithromycin: OD | 60 | Poland | Compliance* | ||

| Clarithromycin: BID | 62 | |||||

| Community-acquired pneumonia/acute bronchitis | Spiritus59,† | Clarithromycin: BID | 311 | 2 | USA | Health care resource utilization* |

| Erythromycin stearate: QID | 321 | |||||

| Cefaclor: TID | 302 | |||||

| Streptococcal pharyngitis | Raz60 | Penicillin V: BID | 51 | 4 | NR | Compliance |

| Penicillin V: QID | 53 | |||||

| Renal transplantation | Abecassis61,† | Tacrolimus + mycophenolate mofetil: OD | NR | NR | USA | Economic outcomes (patient treatment cost)* |

| Tacrolimus + mycophenolate mofetil: BID | NR | |||||

| Sidhu9,† | Tacrolimus: OD | NR | NR | UK | Economic outcomes | |

| Tacrolimus: BID | NR | |||||

| Liver transplant | Eberlin62 | Tacrolimus OD: post transplantation duration > 6 months to <2 years | 16 | 52 | NR | Compliance* |

| Tacrolimus OD: post transplantation duration > 2 to <5 years | 22 | |||||

| Tacrolimus OD: post transplantation duration > 5 years | 21 | |||||

| Tacrolimus BID: post transplantation duration > 6 months to <2 years | 15 | |||||

| Tacrolimus BID: post transplantation duration > 2 to <5 years | 23 | |||||

| Tacrolimus BID: post transplantation duration > 5 years | 22 | |||||

| Ulcerative colitis | Hawthorne28 | Asacol®: OD | 103 | 52 | UK | Adherence |

| Asacol®: TID | 110 | |||||

| Lachaine63 | Mesalamine at 13 weeks: OD | 12 | 52 | Canada | Adherence*, persistence*, compliance | |

| Mesalamine at 13 weeks: >OD | 10 | |||||

| Mesalamine at 26 weeks: OD | 12 | |||||

| Mesalamine at 26 weeks: >OD | 10 | |||||

| Kane26 | Mesalamine: OD | 12 | 26 | USA | Adherence, medication consumption rates | |

| Mesalamine: >OD | 10 | |||||

| Connolly64,† | Mesalazine: OD | NR | NR | UK | Cost (total and direct), ICER, QALY | |

| Mesalazine: BID | NR | |||||

Notes:

Primary outcome;

economic study.

Abbreviations: ART, anti-retroviral therapy; BID, twice daily; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; HIV/AIDS, human imunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; ICER, incremental cost effectiveness ratio; ISMN, isosorbide mononitrate nitroglycerin; MEMS, medication event monitoring system; MPR, medication possession ratio; NR, not reported; OD, once daily; QID, four-times daily; SR, sustained release; TID, three times daily; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; XL, extended release.

Overall associations

Overall association of adherence with dosing frequencies

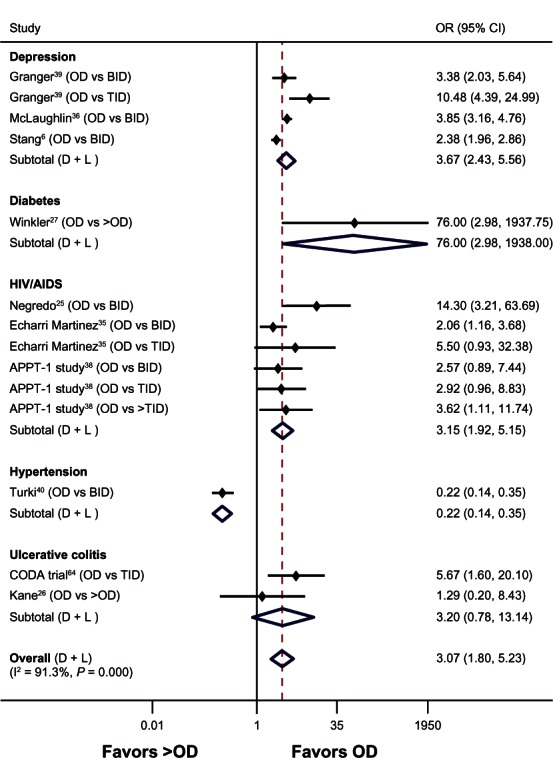

Random-effects meta-analysis was conducted on pooled ORs derived from various disease conditions to compare OD versus BID, BID versus TID, and OD versus > OD regimens in terms of adherence. OD dosing was associated with significantly better adherence rates compared with BID (seven studies, OR 2.20, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.09–4.41, P = 0.027, I2 = 95.5%). No significant difference was observed between BID and TID dosing (three studies, OR 1.88, 95% CI 0.85–4.13, P = 0.118, I2 = 61.9%). OD dosing showed significantly greater adherence rates compared with > OD dosing (ten studies, OR 3.07, 95% CI 1.80–5.23, P < 0.001, I2 = 91.3%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the odds ratios and 95% CIs for adherence rates associated with dosing schedules (once daily versus > once daily) of medications in all diseases.

Note: The broken line indicates overall effect relative to the comparator.

Abbreviations: BID, twice daily; CI, confidence interval; D + L, DerSimonian and Laird technique for meta-analysis; OD, once daily; OR, odds ratio; TID, three times daily; vs, versus; I2, statistical heterogeneity.

A random-effects model regression plot using 13 point estimates (ten studies) for adherence using OD dosing as reference showed that an increase by one dose daily (eg, OD to BID) resulted in a twofold reduction in the odds of adherence (OR 2.03, 95% CI 1.84–7.46).

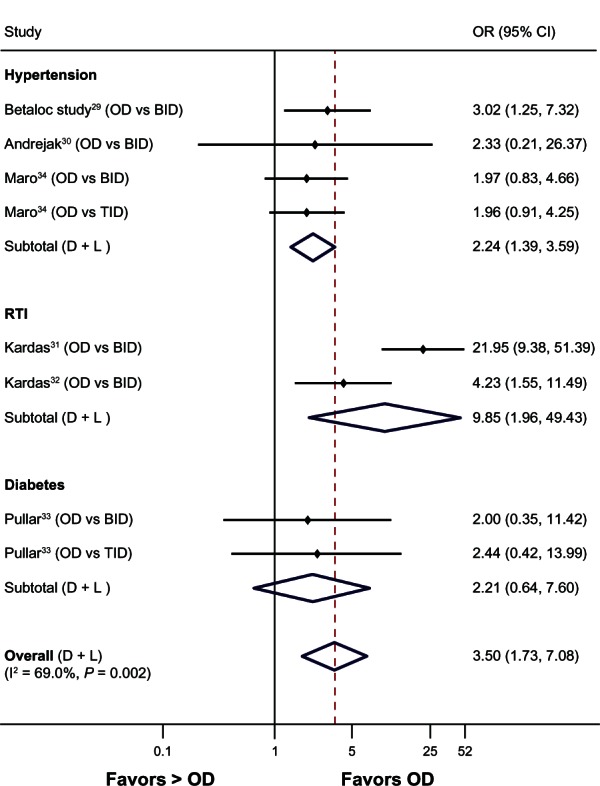

Overall association of compliance with dosing frequencies

Random-effects meta-analysis of pooled ORs across disease conditions demonstrated OD dosing had significantly better compliance than >OD dosing (six studies, OR 3.50, 95% CI 1.73–7.08, P < 0.001, I2 = 69.0%) (Figure 3). A similar trend was observed for OD versus BID dosing (six studies, OR 4.08, 95% CI 1.68–9.91, P = 0.002, I2 = 73.4%).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the odds ratios and 95% CIs for compliance rates associated with dosing schedules (once daily versus > once daily) of medications in all diseases.

Note: The broken line indicates overall effect relative to the comparator.

Abbreviations: BID, twice daily; CI, confidence interval; D + L, DerSimonian and Laird technique for meta-analysis; OD, once daily; RTI, respiratory tract infections; TID, three times daily; vs, versus; OR, odds ratio; I2, statistical heterogeneity.

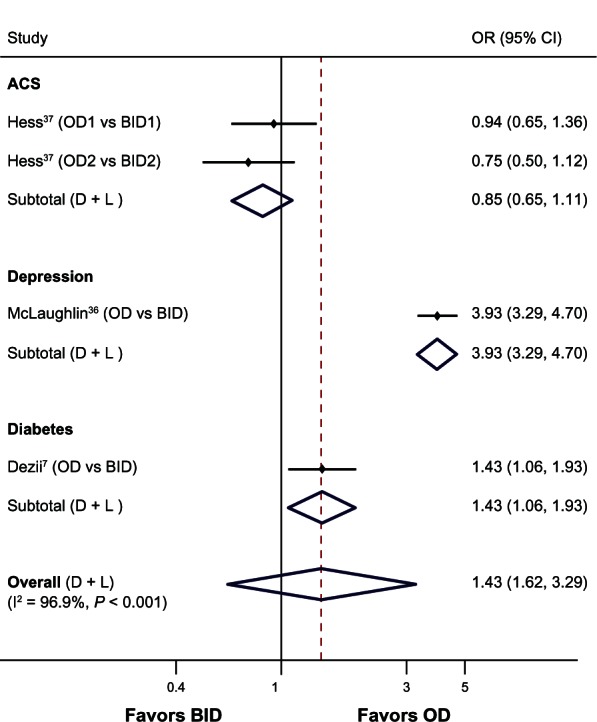

Association of persistence with dosing frequencies

Pooling the data across disease conditions, random-effects meta-analyses illustrated high persistence rates with OD compared with BID dosing (three studies, OR 1.43, 95% CI 0.62–3.29, P = 0.405, I2 = 96.9%) (Figure 4). However, due to considerable heterogeneity between studies, the results should be interpreted with caution.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the odds ratios and 95% CIs for persistence rates associated with OD versus BID dosing schedules of medications in all diseases.

Note: The broken line indicates overall effect relative to the comparator.

Abbreviations: ACS, acute coronary syndrome; BID, twice daily; CI, confidence interval; D + L, DerSimonian and Laird technique for meta-analysis; OD, once daily; vs, versus; OR, odds ratio; I2, statistical heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses conducted by study design indicated no differential effects compared with that of the results indicated by the overall meta-analysis. A higher magnitude of effect was observed with OD compared with the other dosing regimens. For prospective studies,25–34 adherence of OD versus > OD resulted in an OR of 7.11 (95% CI 1.98–25.59, P = 0.003) and compliance of OD versus > OD had an OR of 3.61 (95% CI 1.68–7.78, P = 0.001). In the retrospective studies,6,7,35–37 adherence of OD versus > OD showed an OR of 2.37 (95% CI 1.98–2.83, P < 0.001), and persistence of OD versus BID resulted in an OR of 1.43 (95% CI 0.62–3.27, P = 0.401). Adherence of OD versus > OD in cross-sectional studies37–39 resulted in an OR of 2.39 (95% CI 0.60–9.49, P = 0.217).38–40

Combining the pooled estimates (Z-statistic) between different study designs (cross-sectional, prospective, retrospective, randomized controlled trial [RCT], non-RCT) and analysis types (multivariate, univariate) to examine adherence/persistence/compliance rates for OD dosing versus > OD dosing across disease conditions did not show evidence of bias in results.

Publication bias

Funnel plots showed no marked asymmetry and Egger’s tests demonstrated statistically nonsignificant differences; P = 0.80 for compliance of OD versus > OD in prospective studies and P = 0.24 for adherence of OD versus > OD in cross-sectional studies.41,42 However, visual inspection of the funnel and Egger’s plots indicated that publication bias or other biases cannot be completely ruled out, and such bias might have been introduced in the process of locating, selecting, and combining studies.

Disease-specific association of adherence with dosing frequencies

Cardiovascular disorders

Thirteen studies evaluated the association of adherence/persistence/compliance with different dosing schedules among CV disorders including hypertension,29,30,34,40,43–45 angina pectoris,46,47 atrial fibrillation,10 heart transplant,48 and acute coronary syndrome (Table 3).37

Table 3.

Random effects meta-analyses for association of adherence/compliance/persistence to dosing schedules of medications in various chronic disorders

| Disease | Dose comparison | OR (95% CI); P-value; heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|

| Adherence | ||

| Depression | OD vs BID | 3.10 (2.15–4.47); P < 0.001; I2 = 82.9% |

| Ulcerative colitis | OD vs >OD | 3.20 (0.78–13.14); P = 0.107; I2 = 39.4% |

| OD vs BID | 3.48 (1.32–9.17); P = 0.012; I2 = 64.4% | |

| HIV/AIDS | OD vs TID | 3.48 (1.36–8.90); P = 0.009; I2 = 0% |

| BID vs TID | 1.38 (0.87–2.17); P = 0. 167; I2 = 0% | |

| Across all the diseases | OD vs BID | 2.20 (1.09–4.41); P = 0.027; I2 = 95.5% |

| Across all the diseases | BID vs TID | 1.88 (0.85–4.13); P = 0.118; I2 = 61.9% |

| Across all the diseases | OD vs >OD | 3.07 (1.80–5.23); P < 0.001; I2 = 91.3% |

| Compliance | ||

| Hypertension | OD vs BID | 2.42 (1.33–4.40); P = 0.004; I2 = 0% |

| Infections | OD vs BID | 9.85 (1.96–49.43); P = 0.005; I2 = 83.4% |

| Diabetes | OD vs >OD | 2.24 (1.38–3.66); P = 0.001; I2 = 0.0% |

| Across all the diseases | OD vs BID | 4.08 (1.68–9.91); P = 0.002; I2 = 73.4% |

| Across all the diseases | OD vs >OD | 3.50 (1.73–7.08); P < 0.001; I2 = 69.0% |

| Persistence | ||

| Cardiovascular disorders | OD vs BID | 0.85 (0.65–1.11); P = 0.235; I2 = N/A |

| Across all the diseases | OD vs BID | 1.43 (0.62–3.29); P = 0.405; I2 = 96.9% |

Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; BID, twice daily; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; I2, statistical heterogeneity; N/A, not applicable; OD, once daily; OR, odds ratio; TID, three times daily; vs, versus.

Random-effect meta-analysis for compliance indicated that OD dosing was associated with significantly higher compliance rates compared with BID dosing in three studies (OR 2.42, 95% CI 1.33–4.40, P = 0.004, I2 = 0%) (Table 3).29,30,34 Patients with OD dosing were approximately 2.5 times as likely to comply with therapy than BID dosing of antihypertensive medications. Similarly, random-effect meta-analysis for persistence to medications for acute coronary syndrome showed no difference between OD and BID dosing (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.65–1.11, P = 0.235, I2 = not applicable).37

In contrast to the above results, Turki and Sulaiman40 showed significantly greater adherence with multiple doses (BID and >BID) of antihypertensive medications compared with OD dosing (P < 0.001). All other empirical studies on CV disorders (atrial fibrillation, heart transplant, and angina) demonstrated an improvement in adherence, compliance, and persistence to OD dosing compared with BID dosing.10,47–49

Brown et al46 developed a decision-analytic model to compare costs of treating exercise-induced angina with OD versus BID isosorbide mononitrate. Fewer medical resources were consumed by patients treated with OD versus BID dosing. The economic data suggested that, even though the per-tablet cost of OD was more than BID, the annual patient management costs were nearly the same for both regimens due to better compliance with the OD regimen (Table 4).46

Table 4.

Studies presenting data on costs associated with adherence or compliance

| Study | Disease | Type of evaluation | Results | Study conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown46 | Angina | Decision-analytic model | • Estimated total NHS annual cost for ISMN OD management: GB £248 • Estimated total NHS annual cost for ISMN OD management: GB £250 |

• Fewer health service resources were consumed by patients treated on OD regimen, with a higher compliance rate, compared to a BID regimen |

| Sidhu9 | Renal transplant | Budget impact analysis | • Once daily tacrolimus yielded cumulative cost savings of GB £104,534 | • Use of OD therapy could yield cost savings over five years in comparison to BID therapy of tacrolimus |

| Abecassis61 | Renal transplant | Cost-effectiveness analysis | • Total direct cost with OD therapy: US$228,734 • Total direct cost with BID therapy: US$238,144 |

• Tacrolimus OD resulted in a reduction of costs relative to BID tacrolimus • Tacrolimus OD was the dominant therapy in the cost-effectiveness analysis |

Note: 1 GBP = 1.5 USD.

Abbreviations: BID, twice daily; ISMN, isosorbide mononitrate nitroglycerin; OD, once daily dosing; NHS, UK National Health Service.

Neurological disorders

Neurological disorders such as depression,6,36,39,50 epilepsy,51 and schizophrenia52 were studied in six trials. Three studies in patients with depression6,35,38 contributed adherence data for meta-analysis (Table 3). Random-effect meta-analysis showed that OD dosing was associated with nearly three times higher adherence compared with BID dosing (OR 3.10, 95% CI 2.15–4.47, P < 0.001, I2 = 82.9%).

Pfeiffer et al52 demonstrated that a decrease in daily dosing frequency resulted in a small but significant increase in adherence measured using antipsychotic mean MPR change of 0.45 compared with −0.018 for schizophrenic patients without dosing frequency change (P < 0.001). Cramer et al51 reported mean compliance rates of 87%, 81%, 77%, and 39% with antiepileptics prescribed as OD, BID, TID, and QID regimens, respectively. Overall, results of other empirical studies demonstrated that a decrease in daily dosage frequency was associated with increased adherence, compliance, or persistence (Table 2).6,36,39,50

Pain

There was little published evidence on adherence to treatments for pain. Two studies, one of which was observational53 and one that was economic,54 provided data regarding compliance and costs associated with adherence to pain medications, respectively (Table 2). In the observational study,53 patients on OD propranolol for treating migraine demonstrated higher mean compliance rates (79.8%) than those on BID atenolol (60.0%). Patients on BID atenolol in turn showed better compliance than TID pizotifen or TID methysergide (54.2%); however, the differences were not substantial.

An economic evaluation using a 3-month decision model of three first-line medications for diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain by Carlos et al54 comparing duloxetine OD, pregabalin BID, and gabapentin TID demonstrated that in comparison to TID and BID, OD dosing was associated with a comparative cost savings of US$98 and US$129 per patient, respectively (Table 4). Incremental cost per QALY gained with OD over TID was US$8821 (over the patients dosing lifetime).

Diabetes

Five studies presented data on adherence, compliance, or persistence to medications in type 2 diabetes.7,27,33,55,56 Random-effect meta-analysis for the assessment of compliance on data from two studies indicated OD dosing was associated with a significantly greater compliance rate compared with >OD dosing (OR 2.24, 95% CI 1.38–3.66, P = 0.001, I2 = 0.0%) (Table 3).54,55 The remaining studies demonstrated that adherence rates varied with different assessment techniques; however, OD dosing had better adherence rates than BID/TID regimens.7,26,32

HIV infection

It was observed from six studies of antiretroviral treatments for HIV that regimens prescribed in a TID schedule were more likely to be missed compared with regimens prescribed less than TID.8,25,35,38,57,58

The results of random-effect meta-analysis from three studies in HIV patients indicated that the likelihood of being adherent was significantly higher with OD regimens compared with BID (OR 3.48, 95% CI 1.32–9.17, P = 0.012, I2 = 64.4%) and TID (OR 3.48, 95% CI 1.36–8.90, P = 0.009, I2 = 0%).24,34,37 However, for the BID versus TID comparison, no statistically significant difference was observed (OR 1.38, 95% CI 0.87–2.17, P = 0.167, I2 = 0%) (Table 3).

Infections

Studies of infections included patients with respiratory tract infections (RTIs),31,32 community-acquired pneumonia/acute bronchitis and streptococcal pharyngitis.59,60 Random-effect meta-analysis on data from two studies assessing compliance to antibiotic therapy among patients with RTIs demonstrated that OD dosing was nearly ten times as likely to achieve compliance relative to BID (OR 9.85, 95% CI 1.96–49.43, P = 0.005, I2 = 83.4%) (Table 3).31,32 For streptococcal pharyngitis, Raz et al60 found a significant difference in compliance rates between BID (90%) and QID therapies (58%) (P < 0.001).

Spiritus et al59 randomized patients with lower RTI to clarithromycin BID, erythromycin QID, or cefaclor TID. The authors in this study observed that the per-patient costs of health care resource utilization were US$191 for BID, US$264 for QID, and US$388 for TID (Table 4). Hospitalization costs were comparatively lower with BID (US$28,769 for 305 patients) compared with QID (US$73,322 for 316 patients) and TID (US$78,734 for 289 patients).59

Transplants

Two studies assessed the economic impact of adherence to immunosuppressants among patients undergoing kidney transplantation,9,61 and one observational study evaluated compliance with interventions for liver transplantation.62 Abecassis et al61 modeled patient outcomes and treatment costs over 5 years for renal transplant comparing BID with OD tacrolimus (Table 4). Fewer patients were adherent to BID compared with OD immunosuppressants. Use of OD tacrolimus resulted in a reduction in 5-year discounted average patient total treatment costs relative to BID tacrolimus (US$228,734 versus US$238,144).61 Similarly, Sidhu et al9 calculated a 74% probability of adherence with OD versus 55% with BID tacrolimus (Table 4). Over 5 years, the OD regimen yielded cumulative cost savings relative to BID of £104,534, including savings in drug acquisition (£69,180), management of acute rejection episodes (£22,837), retransplantation (£417), and dialysis (£13,631).9 Further, Eberlin and Kramer62 demonstrated that switching patients from BID to OD tacrolimus-based regimen for liver transplantation resulted in a trend towards better compliance with OD regimen.

Ulcerative colitis

Three studies examined different dosing schedules of treatments for ulcerative colitis with adherence and persistence to medications,26,28,63 and another study presented data on the associated economic impact (Table 2).64 Random-effect meta-analysis on treatment adherence for ulcerative colitis indicated that OD dosing was associated with better adherence compared with >OD dosing (OR 3.20, 95% CI 0.78–13.14, P = 0.107, I2 = 39.4%).25,27 Lachaine et al63 reported that adherence and persistence to mesalazine formulations were relatively poor; however, improved adherence and persistence were observed with OD dosing.

Connolly et al64 conducted an economic evaluation comparing OD with BID mesalazine based on results from an RCT (Table 4). Average annual costs per person treated with OD or BID mesalazine, including costs of treatment failure were £815 and £971, respectively, with an annual cost-savings (incremental cost per year) of £156 when using an OD regimen. OD had >0.95 probability of being cost-effective compared with BID based on accepted willingness to pay thresholds applied by the UK National Health Service.64

Discussion

Drug regimen complexity, ie, taking multiple daily doses of an intervention, is a critical factor affecting medication-taking behavior. The current analysis demonstrated that reducing the dosing regimen complexity improves adherence, compliance, and/or persistence. Across a variety of studied conditions, OD dosing of oral medications was associated with higher adherence compared with multiple-dosing schedules, which in turn may have led to decreased health care costs.

Our results are consistent with those found in empirical studies and literature reviews, including published metaanalyses, that showed adherence is inversely proportional to the number of medication doses per day.15,16,18–20,65,66 A systematic review of 76 studies (1986–2000) by Claxton et al16 to measure compliance found that simpler, less frequent dosing regimens resulted in better compliance across a variety of therapeutic classes. A review by Shi et al15 of the effect of dose frequency on compliance between 1966 and 2006 showed that reducing dose frequency via new dosage forms and formulations may improve medication compliance. Similarly, the recent meta-analysis by Coleman et al20 that included studies up to December 2011 found mean weighted adherence rates that were progressively lower as dosing frequency increased. The results of our quantitative analysis were also consistent with findings reported by other meta-analyses conducted specifically in the disease areas of hypertension and HIV infection.18,19

Economic evidence associated with adherence was reported in a variable manner; therefore, quantitative analyses were not possible. However, descriptive evaluation of the available evidence suggested less consumption of medical resources with OD dosing compared with BID dosing. More research is needed to quantify the extent and precision of the magnitude of effect.

This analysis could potentially be criticized for analyzing compliance and adherence seperately. However, our analysis was based on the terms used in the original studies, since ISPOR definitions consider these two terms to be synonymous.12 In this regard, it should be noted that, although ISPOR definitions consider these two terms to be synonymous, differences have been noted in how these terms are used. Within the published literature, adherence has also been defined as a health plan constructed and agreed to by the patient in partnership with a health care provider in clinical decision making, while compliance implies a one way relationship; the clinician dictates the medical regimen, and the patient is expected to comply.67 A related limitation of this review is that the studies largely reported adherence based on patient self-report, rather than objective measures such as blood level monitoring, prescription refills, and electronic monitoring, making the studies subject to patient recall bias.68 Nevertheless, despite these two limitations, there was general concordance of results between compliance and adherence in our analysis.

A meta-analysis can generate inherent biases when combining data from different studies with variable sample sizes, study designs, and outcome definitions. In our meta-analysis, all variables that could affect adherence, other than daily dose frequency, were assumed to be equal among comparators, which may not hold true in real-world settings. Data were combined from studies that used various definitions of adherence, compliance, and persistence, which is another limitation of this review. In addition, as persistence is a time-related event, studies assessing persistence used different methodologies and time points to assess this outcome. This difference was also reflected by the high heterogeneity associated with the meta-analysis results of overall persistence. However, random effects meta-analysis was employed to take into account heterogeneity due to potential confounding factors. Further, sensitivity analysis with respect to study designs to explore the impact of heterogeneity on the results revealed that higher adherence, compliance, and persistence were observed with OD versus > OD. These results were consistent with the findings of other random-effects meta-analyses.

It should also be noted that some studies utilized different medications for the different dosing regimens. Thus, it is possible that there may have been factors other than the dosing frequency that may have contributed to the observed patterns of adherence/compliance, such as side-effects, size of tablet or capsule, taste, timing of administration (morning or evening, with or without food). While this may also represent a limitation of the current study, to our knowledge, factors that may relate to patient preference of medications and their impact on adherence, are rarely included in published studies and difficult to account for in such meta-analyses.

Knowing that poor treatment adherence/compliance/ persistence is a problem in chronic pain patients, we found only two published studies addressing the relationship of adherence to treatment regimens in this population. Additional research is required to better characterize the nature and correlates of nonadherence (or noncompliance or nonpersistence) in patients being treated for chronic pain conditions. This lack of data also highlights the need for correlating adherence with economic outcomes in chronic pain. Although such a correlation was assessed in several other conditions, the overall paucity of studies investigating the impact of adherence on health care resource utilization and costs suggests that this represents an important research gap. An additional need is more detailed analysis of the relationship between dosing frequency and clinical outcomes.

Despite these limitations, there are several strengths to this review. The methodology involved was rigorous and followed stringent PRISMA guidelines. The effect of pooling different study designs and analysis types for examining overall adherence rates across different dosing schedules showed no evidence of bias in the results. The quantitative and descriptive evidence both indicated that the limitations considered did not change the overall observation that a reduction in dosing frequency resulted in better adherence, which may have contributed to a reduction in health care costs. Finally, our analysis was not limited to RCTs; rather, it included all published study designs.

Conclusion

Access to simplified dosage regimens by patients may be an important aspect in maximizing therapeutic success. The current meta-analysis suggested that the prescribed number of doses per day was inversely proportional to adherence/compliance/persistence across all acute and chronic conditions evaluated. In turn, poor adherence to medication regimens may result in greater consumption of medical resources, which in turn may lead to increased health care costs. Clinicians should be aware that medication adherence is a complex phenomenon with several factors at play and efforts to improve adherence should not be restricted to prescription of OD medications.69,70 Other factors, including potency, tolerability, and risk of resistance to medications, in addition to patient’s individual adherence patterns, are important considerations when selecting the optimal course of therapy for patients.

Appendix.

Appendix.

Study protocol listing the eligibility criteria for inclusion/exclusion of studies in the review as per the PRISMA guidelines

| Clinical effectiveness | Rationale | |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria | Population | The population of interest to the review includes patients of any age, race, and gender receiving any oral medication for any chronic disease |

| • Age: Adults (≥ 18 years) | ||

| • Gender: Any | ||

| • Race: Any | ||

| • Qualifying event/disease/factors: Any chronic disease | ||

| Intervention | The review aimed to compare adherence/compliance/ persistence associated with different dosing regimens rather than any particular intervention | |

| • Any oral intervention administered as OD, BID, TID, QID | ||

| Comparator | The comparator of interest was a different dosage regimen of the interventions being evaluated in the study. Since the review required direct evidence on adherence of dosing regimens of interventions, placebo/best supportive care (BSC) as comparators were not included | |

| • Any oral intervention administered as OD, BID, TID, QID | ||

| Study design | Observational studies and economic evidence were the best source of adherence/compliance data as they reflect ‘real life’ and were considered for the review. | |

| • Comparative cohort studies/longitudinal studies (retrospective) | ||

| • Comparative cohort studies/longitudinal studies (prospective) | ||

| • Published database analyses/registries | ||

| • Case-control studies | ||

| • Cross-sectional study—comparative | ||

| • Randomized controlled trials | ||

| • Non-randomized controlled trials | ||

| • Economic studies | ||

| Language restrictions | Studies with the full-text publication in English only were included in this review | |

| • English only | ||

| Publication timeframe | No date restriction was applied in order to capture the maximum amount of adherence data | |

| • No date restriction for database searches | ||

| Exclusion criteria | Outcome of interest | Only studies reporting data pertaining to adherence/ compliance/persistence and healthcare costs associated with non-adherence were included in the review |

| • Studies that did not report the outcomes of interest (adherence/ compliance/persistence and healthcare costs associated with non-adherence) were excluded from the review | ||

| Route of administration | Studies assessing interventions administered only through an oral route were included in the current review | |

| • Studies evaluating interventions administered via a non-oral route were excluded |

Abbreviations: BID, twice daily; BSC, best supportive care; OD, once daily; QID, four times daily; TID, three times daily.

Footnotes

Disclosure

This research was supported by Pfizer Inc. Alesia Sadosky and Joseph C Cappelleri are paid employees of Pfizer Inc. Kunal Srivastava, Anamika Arora, and Aditi Kataria are employees of Heron Health who were paid consultants to Pfizer Inc in the development and execution of this study and publication related deliverables. Andrew M Peterson was not financially compensated for his collaboration on this project including publication related activities.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Failure to take prescribed medicine for chronic diseases is a massive, world-wide problem [news release] Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2003/pr54/enAccessed February 12, 2013

- 2.Jackevicius CA, Mamdani M, Tu JV. Adherence with statin therapy in elderly patients with and without acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2002;288(4):462–467. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunbar-Jacob J, Erlen JA, Schlenk EA, Ryan CM, Sereika SM, Doswell WM. Adherence in chronic disease. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2000;18:48–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stuart B, Briesacher B. Medication decisions – right and wrong. Med Care Res Rev. 2002;59(2):123–145. doi: 10.1177/1077558702059002001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kyngas H, Lahdenpera T. Compliance of patients with hypertension and associated factors. J Adv Nurs. 1999;29(4):832–839. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stang P, Suppapanaya N, Hogue SL, Park D, Rigney U. Persistence with once-daily versus twice-daily bupropion for the treatment of depression in a large managed-care population. Am J Ther. 2007;14(3):241–246. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e31802b59e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dezii CM, Kawabata H, Tran M. Effects of once-daily and twice-daily dosing on adherence with prescribed glipizide oral therapy for type 2 diabetes. South Med J. 2002;95(1):68–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrieri MP, Leport C, Protopopescu C, et al. Factors associated with nonadherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: a 5-year follow-up analysis with correction for the bias induced by missing data in the treatment maintenance phase. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(4):477–485. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000186364.27587.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sidhu M, Lees L, Warner J. Five-year budget impact analysis of once-daily versus twice-daily tacrolimus, in patients undergoing renal transplant in the United Kingdom [abstract] Value Health. 2010;13:A170. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song X, Sander S, Varker H, Amin A. Patterns and predictors of persistence of warfarin and other commonly-utilized chronic medications among patients with atrial fibrillation [abstract] Value Health. 2010;13:A170. [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004;42(3):200–209. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114908.90348.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008;11(1):44–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnsten JH, Gelfand JM, Singer DE. Determinants of compliance with anticoagulation: a case-control study. Am J Med. 1997;103(1):11–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)90048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi L, Hodges M, Yurgin N, Boye KS. Impact of dose frequency on compliance and health outcomes: a literature review (1966–2006) Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2007;7(2):187–202. doi: 10.1586/14737167.7.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Ther. 2001;23(8):1296–1310. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richter A, Anton SE, Koch P, Dennett SL. The impact of reducing dose frequency on health outcomes. Clin Ther. 2003;25(8:):2307–2335. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80222-9. discussion 2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iskedjian M, Einarson TR, MacKeigan LD, et al. Relationship between daily dose frequency and adherence to antihypertensive pharmacotherapy: evidence from a meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2002;24(2):302–316. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)85026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parienti JJ, Bangsberg DR, Verdon R, Gardner EM. Better adherence with once-daily antiretroviral regimens: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(4):484–488. doi: 10.1086/596482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coleman CI, Limone B, Sobieraj DM, et al. Dosing frequency and medication adherence in chronic disease. J Manag Care Pharm. 2012;18(7):527–539. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2012.18.7.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4:):264–269. W264. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berlin JA, Antman EM. Advantages and limitations of metaanalytic regressions of clinical trials data. Online J Curr Clin Trials. 1994 Jun 4; doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(92)90151-o. Doc No 134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Negredo E, Molto J, Munoz-Moreno JA, et al. Safety and efficacy of once-daily didanosine, tenofovir and nevirapine as a simplification antiretroviral approach. Antivir Ther. 2004;9(3):335–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kane S, Huo D, Magnanti K. A pilot feasibility study of once daily versus conventional dosing mesalamine for maintenance of ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1(3):170–173. doi: 10.1053/cgh.2003.50025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winkler A, Teuscher AU, Mueller B, Diem P. Monotoring adherence to prescribed medication in type 2 diabetic patients treated with sulfonylureas. Swiss Med Wkly. 2002;132(27–28):379–385. doi: 10.4414/smw.2002.10036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hawthorne AB, Stenson R, Gillespie D, et al. Once daily mesalazine as maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis (UC): a one-year single-blind randomized trial [abstract] Gastroenterology. 2011;140(Suppl):S65. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baird MG, Bentley-Taylor MM, Carruthers SG, et al. A study of efficacy, tolerance and compliance of once-daily versus twice-daily metoprolol (Betaloc) in hypertension. Betaloc Compliance Canadian Cooperative Study Group. Clin Invest Med. 1984;7(2):95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrejak M, Genes N, Vaur L, Poncelet P, Clerson P, Carre A. Electronic pill-boxes in the evaluation of antihypertensive treatment compliance: comparison of once daily versus twice daily regimen. Am J Hypertens. 2000;13(2):184–190. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(99)00175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kardas P. Once-daily dosage secures better compliance with antibiotic therapy of respiratory tract infections than twice daily dosage. J Appl Res. 2003;3(2):201–206. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kardas P. Comparison of patient compliance with once-daily and twice-daily antibiotic regimens in respiratory tract infections: results of a randomized trial. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59(3):531–536. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pullar T, Birtwell AJ, Wiles PG, Hay A, Feely MP. Use of a pharmacologic indicator to compare compliance with tablets prescribed to be taken once, twice, or three times daily. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988;44(5):540–545. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1988.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maro EE, Lwakatare J. Medication compliance among Tanzanian hypertensives. East Afr Med J. 1997;74(9):539–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Echarri Martinez LE, Rodriguez Gonzalez CG, Castillo Romera I, et al. Evolution of adherence to antiretroviral treatment in a Spanish hospital during 2001, 2005, and 2008. Lat Am J Pharm. 2011;30:1173–1178. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLaughlin T, Hogue SL, Stang PE. Once-daily bupropion associated with improved patient adherence compared with twice-daily bupropion in treatment of depression. Am J Ther. 2007;14(2):221–225. doi: 10.1097/01.mjt.0000208273.80496.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hess G, Bhandary D, Fonseca E, et al. Adherence to medications with once-a-day (qd) and twice-a-day (bid) dosing formulations in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients [abstract] Value Health. 2011;14:A44. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moyle G. The Assessing Patients’ Preferred Treatments (APPT-1) study. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14(Suppl 1):34–36. doi: 10.1258/095646203322491860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Granger AL, Fehnel SE, Hogue SL, Bennett L, Edin HM. An assessment of patient preference and adherence to treatment with Wellbutrin SR: a web-based survey. J Affect Disord. 2006;90(2–3):217–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turki AK, Sulaiman SAS. Adherence to antihypertensive therapy in general hospital of Penang: does daily dose frequency matter? Jordan J Pharm Sci. 2009;2:167–175. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Celis H, Staessen J, Fagard R, Thijs L, Amery A. Does isradipine modified release 5 mg once daily reduce blood pressure for 24 hours? J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1993;22(2):300–304. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199308000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Girvin B, McDermott BJ, Johnston GD. A comparison of enalapril 20 mg once daily versus 10 mg twice daily in terms of blood pressure lowering and patient compliance. J Hypertens. 1999;17(11):1627–1631. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917110-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boissel JP, Meillard O, Perrin-Fayolle E, et al. Comparison between a bid and a tid regimen: improved compliance with no improved antihypertensive effect. The EOL Research Group. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;50(1–2):63–67. doi: 10.1007/s002280050070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown RE, Kendall MJ, Halpern MT. Cost analysis of once-daily ISMN versus twice-daily ISMN or transdermal patch for nitrate prophylaxis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1997;22(1):67–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.1997.8475084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kardas P. Compliance, clinical outcome, and quality of life of patients with stable angina pectoris receiving once-daily betaxolol versus twice daily metoprolol: a randomized controlled trial. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2007;3(2):235–242. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.2007.3.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doesch AO, Mueller S, Konstandin M, et al. Increased adherence after switch from twice daily calcineurin inhibitor based treatment to once daily modified released tacrolimus in heart transplantation: a pre-experimental study. Transplant Proc. 2010;42(10):4238–4242. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.09.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bae JP, Anderson J, Zagar A, et al. The effects of dosing complexity on adherence with prescription medications commonly used for cardiovascular patients [abstract] Value Health. 2010:A360. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stang P, Young S, Hogue S. Better patient persistence with once-daily bupropion compared with twice-daily bupropion. Am J Ther. 2007;14(1):20–24. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e31802b5954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cramer JA, Mattson RH, Prevey ML, Scheyer RD, Ouellette VL. How often is medication taken as prescribed? A novel assessment technique. JAMA. 1989;261(22):3273–3277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pfeiffer PN, Ganoczy D, Valenstein M. Dosing frequency and adherence to antipsychotic medications. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(10):1207–1210. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.10.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mulleners WM, Whitmarsh TE, Steiner TJ. Noncompliance may render migraine prophylaxis useless, but once-daily regimens are better. Cephalalgia. 1998;18(1):52–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1998.1801052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carlos F, Ramirez J, Galindo-Suarez RM, Duenas H. PDB33 Economic evaluation of three first-line medications in painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in Mexico. Value in Health. 2010;13(3):A60. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kardas P. The DIACOM study (effect of DosIng frequency of oral Antidiabetic agents on the COMpliance and biochemical control of type 2 diabetes) Diabetes Obes Metab. 2005;7(6):722–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2004.00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Charpentier G, Fleury F, Dubroca I, Vaur L, Clerson P. Electronic pill-boxes in the evaluation of oral hypoglycemic agent compliance. Diabetes Metab. 2005;31(2):189–195. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stone VE, Hogan JW, Schuman P, et al. Antiretroviral regimen complexity, self-reported adherence, and HIV patients’ understanding of their regimens: survey of women in the her study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;28(2):124–131. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200110010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abellan J, Garrote M, Pulido F, Rubio R, Costa JR. Evaluation of adherence to a triple antiretroviral therapy in HIV-positive patients. Eur J Intern Med. 1999;10(4):202–205. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spiritus EM, Chang RJ, Zhang JX, et al. Cost savings of clarithromycin compared with erythromycin or cefaclor in the treatment of lower respiratory tract infection: Results of a randomized, multicenter study. Am J Manag Care. 1998;4(Suppl 11):S562–S570. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Raz R, Elchanan G, Colodner R, et al. Penicillin V twice daily vs four times daily in the treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 1995;4(1):50–54. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abecassis MM, Seifeldin R, Riordan ME. Patient outcomes and economics of once-daily tacrolimus in renal transplant patients: results of a modeling analysis. Transplant Proc. 2008;40(5):1443–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.03.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eberlin MB, Kramer I. Evaluation of medication compliance of liver transplant patients switched from a twice-daily to a once-daily tacrolimus-based regimen [abstract] Pharm World Sci. 2010;32:670–671. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lachaine J, Beauchemin C, Yen L, Hodgkins P. Medication adherence and persistence in the treatment of ulcerative colitis analyses with the RAMQ database [abstract] Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25(Suppl A) doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-23. Abstract A072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Connolly MP, Nielsen SK, Currie CJ, Poole CD, Travis SP. An economic evaluation comparing once daily with twice daily mesalazine for maintaining remission based on results from a randomised controlled clinical trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2009;3(1):32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fischer RG. Compliance-oriented prescribing: simplifying drug regimens. J Fam Pract. 1980;10(3):427–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bae JP, Dobesh PP, Klepser DG, et al. Adherence and dosing frequency of common medications for cardiovascular patients. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(3):139–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gould E, Mitty E. Medication adherence is a partnership, medication compliance is not. Geriatr Nurs. 2010;31(4):290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Urquhart J. Ascertaining how much compliance is enough with outpatient antibiotic regimens. Postgrad Med J. 1992;68(Suppl 3):S49–S58. discussion S59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Petersen ML, Wang Y, van der Laan MJ, Guzman D, Riley E, Bangsberg DR. Pillbox organizers are associated with improved adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy and viral suppression: a marginal structural model analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):908–915. doi: 10.1086/521250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Simoni JM, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Marks G, Crepaz N. Efficacy of interventions in improving highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence and HIV-1 RNA viral load. A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(Suppl 1):S23–S35. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248342.05438.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]