Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to develop a methodology to quantitatively measure the thorax-to-abdomen breathing ratio from a 4DCT dataset for breathing motion modeling and breathing motion studies.

Methods: The thorax-to-abdomen breathing ratio was quantified by measuring the rate of cross-sectional volume increase throughout the thorax and abdomen as a function of tidal volume. Twenty-six 16-slice 4DCT patient datasets were acquired during quiet respiration using a protocol that acquired 25 ciné scans at each couch position. Fifteen datasets included data from the neck through the pelvis. Tidal volume, measured using a spirometer and abdominal pneumatic bellows, was used as breathing-cycle surrogates. The cross-sectional volume encompassed by the skin contour when compared for each CT slice against the tidal volume exhibited a nearly linear relationship. A robust iteratively reweighted least squares regression analysis was used to determine η(i), defined as the amount of cross-sectional volume expansion at each slice i per unit tidal volume. The sum Ση(i) throughout all slices was predicted to be the ratio of the geometric expansion of the lung and the tidal volume; 1.11. The Xiphoid process was selected as the boundary between the thorax and abdomen. The Xiphoid process slice was identified in a scan acquired at mid-inhalation. The imaging protocol had not originally been designed for purposes of measuring the thorax-to-abdomen breathing ratio so the scans did not extend to the anatomy with η(i) = 0. Extrapolation of η(i)–η(i) = 0 was used to include the entire breathing volume. The thorax and abdomen regions were individually analyzed to determine the thorax-to-abdomen breathing ratios. There were 11 image datasets that had been scanned only through the thorax. For these cases, the abdomen breathing component was equal to 1.11 − Ση(i) where the sum was taken throughout the thorax.

Results: The average Ση(i) for thorax and abdomen image datasets was found to be 1.20 ± 0.17, close to the expected value of 1.11. The thorax-to-abdomen breathing ratio was 0.32 ± 0.24. The average Ση(i) was 0.26 ± 0.14 in the thorax and 0.93 ± 0.22 in the abdomen. In the scan datasets that encompassed only the thorax, the average Ση(i) was 0.21 ± 0.11.

Conclusions: A method to quantify the relationship between abdomen and thoracic breathing was developed and characterized.

Keywords: 4DCT, tidal volume

INTRODUCTION

In radiation therapy, tumor motion resulting from breathing remains an important challenge.1, 2, 3, 4 While methods have been developed to limit this motion, better understanding of the natural breathing cycle remains important. This study was designed to quantify the relative thorax versus the abdomen breathing-induced body expansion. Understanding the relative expansion of thorax and abdomen could be used to guide the design of external breathing surrogates as well as assess the potential for abdominal compression.2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

During inhalation, the torso expands by a volume proportional to the tidal volume. Tidal volume is defined as is the volume of air displaced by the lungs during the act of quiet respiration. The relationship between the torso expansion and tidal volume has been a subject of interest in lung physiology. In 1966, Agostoni et al.12 measured the relationship between the thoracic circumference and the volume of the lung. They defined the thoracic circumference from the apex of the lung in the cranial direction and the level of the dome of the diaphragm in the caudal direction. In the discussion they highlighted the challenge of defining a boundary between the abdomen and thorax during respiration. If the subject intentionally breathed from the chest, the rib cage expansion changed the defined boundary location of the thorax and abdomen in this study. Grassino et al.13 suggested direct measurement of the anteroposterior diameter change of the thorax and abdomen was a valid alternative, provided that the variable length of the chest wall was taken into account. The diaphragm applies pressure to the respiratory system during respiration. This pressure influences the configuration of the chest wall, which in turn increases the variability in which the boundary between the abdomen and the thorax is defined. Konno and Mead,14 in an earlier study of the volume displacement in the thorax claimed the chest wall distended during breathing. With this contribution and assuming the diaphragm contracted isometrically, Grassino et al.13 developed a method of calculating the various chest wall configurations in relation to the diaphragmatic expansion state during respiration. In doing so, they neglected the considerable effect rib cage expansion has on the abdomen where abdominal wall displacement occurs at a fixed diaphragmatic length. Fixed diaphragmatic length refers to controlled breathing where the rib cage expansion is greater than during quiet breathing. This is referred to as thoracic breathing in this paper. Mead and Loring15 analyzed the abdominal displacements caused by the rib cage and claimed the rib cage volume displacement accounted for a significant portion of the total lung volume change. These papers provided a valuable insight into respiration mechanics, the displacement of organs during respiration, and the thorax and abdomen anatomic boundary. However, they were unable to demonstrate and quantify volume conservation during respiration.

Gated radiation therapy uses breathing cycle surrogates to determine the breathing phase in real time.10, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 One such system is a cylindrical bellows that is wrapped around the abdomen. The bellows system does not have the ability to measure the tidal volume of the lung, but it has been used in conjunction with spirometry to quantitatively measure tidal volume. Werner et al.22 developed a method to correlate the spirometry measured tidal volume to the bellows by the CT based air content. The air content was determined from analyzing the volume averaged Hounsfield units of pixels within the lungs. Based on the ideal gas law and the typical temperature and humidity values encountered in clinics, the ratio of internal air content to tidal volume change was calculated to be 1.11.18, 23 Given the relative incompressibility of the abdominal contents, we hypothesized that the ratio of geometric torso expansion to tidal volume in the torso was also 1.11.

The widespread implementation of linear accelerator gating using both thoracic and abdominal surrogates led to the question of how much surface expansion was being expressed in the thorax and abdomen for radiation therapy patients. This work examined the thorax-to-abdomen ratio of expansion, determining the amount of volume change in each region as a function of tidal volume.

METHODS

Data acquisition

This study used a total of 26 patient datasets acquired using a 16-slice CT scanner (Philips 16-slice Brilliance CT) under an IRB approved 4DCT protocol. The dataset was divided into two subsets. The first subset contained 15 patients with images acquired from the chin through the pelvis and the second subset contained 11 patients with only thorax image data. The image acquisition protocol acquired 25 ciné CT scans at abutting couch positions using 40 mAs and 120 kVp. Image reconstruction was performed with a 512 × 512 voxel matrix, an inplane field of view of 50 cm, and 1.5 mm thick slices. A contiguous set of simultaneously acquired 16 CT slices was termed a couch position and each couch position covered 24 mm in the craniocaudal direction. The scans used a 0.46 s gantry rotation, 360° reconstruction, and 0.32 s between each scan. The total duration to acquire the 25 scans in each couch position was 18.2 s. On average, 12 and 25 abutting couch positions were required to span the thorax and torso, respectively.

The tidal volume was determined by simultaneous measurement of a spirometer and an abdominal pneumatic bellows. The spirometer (Interface Associates, Aliso Viejo, CA, VMM 400) had a 1 ml resolution and sampling rate of 100 Hz. To account for known drift in the spirometer signal, the abdominal pneumatic belt (Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH), known as the bellows, was used as an independent metric. The relationship between the bellows and spirometer was found to be highly correlated by Werner et al.22 over a time period equal to the time to scan a single couch position. A linear drift correction was independently applied to the spirometer signal for each couch position and used to convert the bellows signal into tidal volume.

Volume expansion

The volume of the body was measured by masking every scan. The mask discounted pixels beyond the exterior of the skin using a threshold method. The mask pixel volume increased as the tidal volume increased. The relationship between the two measurements was approximated as linear. A robust iteratively reweighted least squares regression analysis24 was used to determine the volume expansion at each slice i per unit tidal volume, defined as η(i). The volume expansion of each slice was summed to calculate the breathing ratio, essentially the rate of body volume increased throughout the thorax and abdomen as a function of tidal volume. The sum Ση(i) throughout all slices was predicted to be the ratio of the geometric expansion of the lung and the tidal volume: 1.11.18, 23 The boundary between the thorax and abdomen was selected to be the Xiphoid process as imaged at or near the 50th percentile tidal volume. The thorax and abdomen regions were individually analyzed to determine the thorax-to-abdomen breathing ratios. The thorax-to-abdomen breathing ratio was defined as the ratio of Ση(i) individually determined for the thorax and the abdomen.

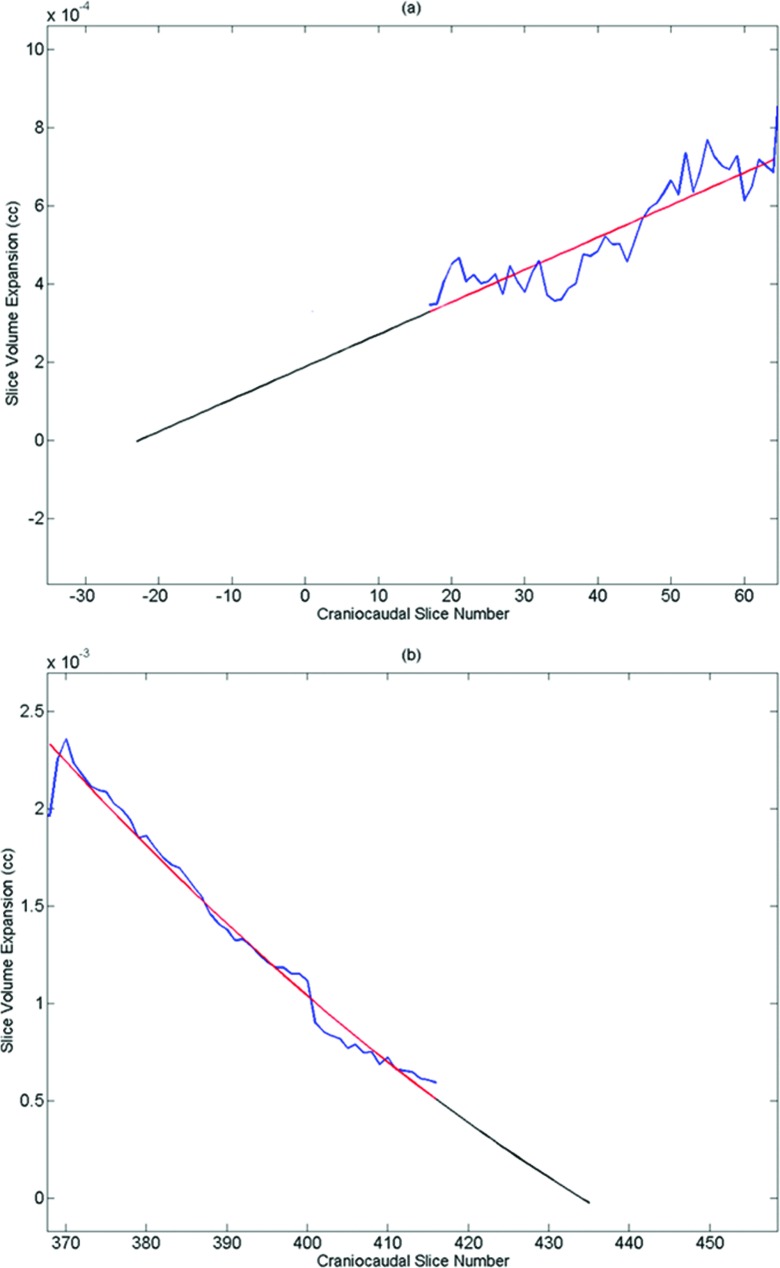

Extrapolation correction

Since the start and end craniocaudal positions of each CT scanning session had not been optimized to support this project, the first and last scans often had nonzero values of η(i). To allow a determination of Ση(i), the values of η(i) were extrapolated until a slice position where η(i) = 0. The values of η(i) decreased monotonically near the superior and inferior scan borders, and polynomials were evaluated to provide the extrapolation. To test the accuracy of the extrapolation, a patient with complete data was corrected with the extrapolation with the data at the beginning and end of the dataset artificially removed and the extrapolation compared with the actual values. A linear extrapolation was used for slices missing data at the neck and a second order polynomial extrapolation was used for slices missing data at the pelvis.

A large spike in the η(i) was found in each patient at a location consistent with the bellows, which had been included in the mask. The presence of the spike was retrospectively corrected for by interpolating η(i) for the slices that contained the bellows with a linear interpolation method. This process introduced <1% uncertainty in Ση(i) for the slices under the bellows.

RESULTS

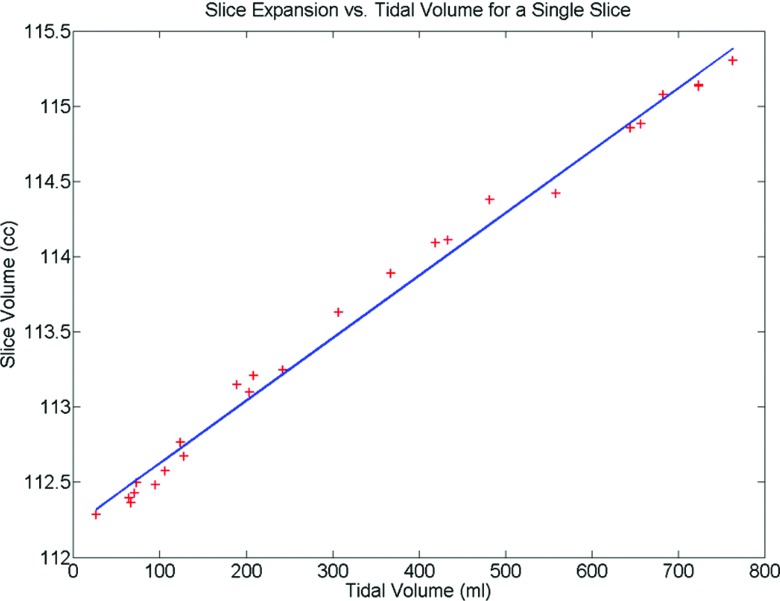

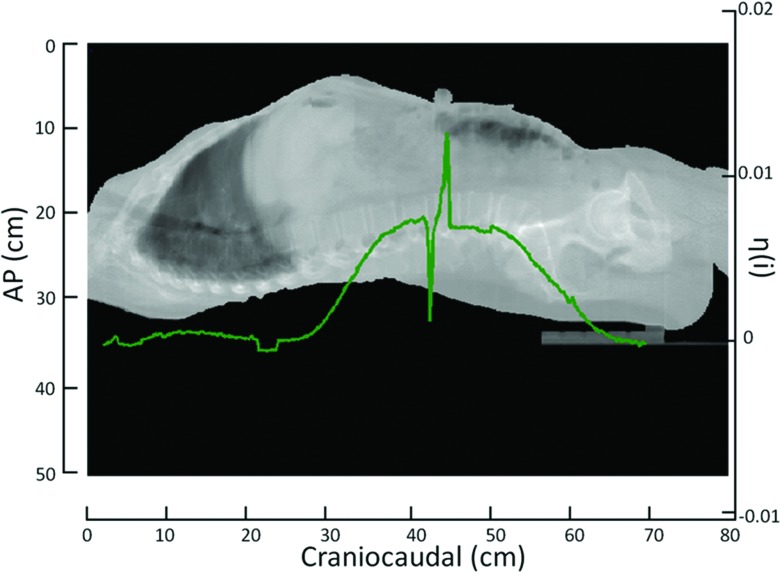

An example of the robust iteratively reweighted least squares regression analysis24 used to determine η(i) for a single slice is illustrated in Fig. 1. The extrapolation correction at the neck and pelvis can be seen in Fig. 2 for a single dataset. The extrapolation correction at the neck was done using a linear regression. The extrapolation correction at the pelvis required a second order polynomial fit. Figure 3 shows an example of the scaled η(i) for each slice in the craniocaudal direction. These values are superimposed on the volumes of a mid-inhalation reconstructed scan.

Figure 1.

An example of the linear relationship between the torso surface volume expansion and the tidal volume.

Figure 2.

Extrapolation example at the neck (a) and the pelvis (b). The fit is shown with the original data and the added extrapolation to zero volume expansion is shown beyond the original data.

Figure 3.

A typical example of η(i) displayed with a 50th percentile tidal volume image displaying the variation of η(i) in the craniocaudal direction. The sharp spike in η(i) occurs at the bellows. The values of η(i) were interpolated through the slices containing the bellows.

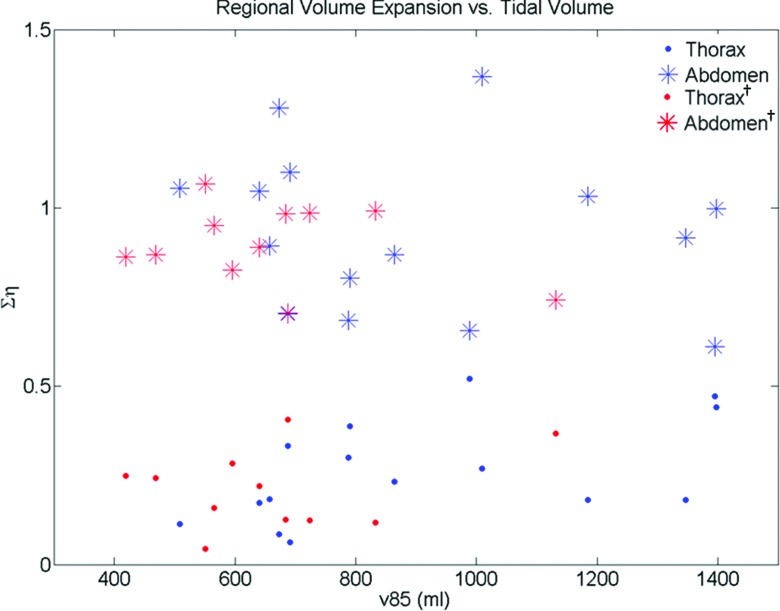

The Xiphoid process was easily identifiable in the 50th percentile tidal volume scan. The Ση(i) results for the 15 patients with data in the thorax and abdomen are provided in Table 1. The results are shown for slices superior to the Xiphoid process [Ση(i) Thorax], slices inferior to the Xiphoid process [Ση(i) Abdomen], all slices [Ση(i) Total], and the thorax-to-abdomen breathing ratio [Ση(i) Th/Ση(i) Ab]. The average Ση(i) Total for these patients was found to be 1.20 ± 0.17. The thorax-to-abdomen breathing ratio was 0.32 ± 0.24. The average Ση(i) Thorax was 0.26 ± 0.14 and the average Ση(i) Abdomen was 0.93 ± 0.22. Table 2 provides the results for the 11 patients imaged only in the thorax region. The results are shown in a similar manner as Table 1. Since these datasets did not have information for slices inferior to the Xiphoid process, Ση(i) Total was assumed to be 1.11 so that Ση(i) Abdomen was calculated by Ση(i) Total − Ση(i) Thorax. The average Ση(i) Thorax for these patients was 0.21 ± 0.11. The average thorax-to-abdomen breathing ratio for these patients was 0.90 ± 0.11. The distribution of Ση(i) versus the 85th tidal volume percentile for the thorax and abdominal regions in both datasets can be seen in Fig. 4. A Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to test the statistical similarity of Ση(i) for the thorax and abdomen between the two datasets. Ση(i) for the thorax in patients that were imaged only in the thorax was statistically similar ( p = 0.44) to the thorax data of patients imaged from the neck through the pelvis. In the dataset that contained images from the neck through the pelvis, Ση(i) in the thorax was distinctly different ( p = 3.4 × 10−6) than the average volume expansion in the abdomen. For the patients imaged only in the thorax, the estimated abdominal volume expansion was statistically similar to the volume expansion of patients imaged in the abdomen ( p = 0.66).

Table 1.

Summary of the results for patients imaged in the thorax and abdominal regions.

| Patient ID | Ση(i) Thorax | Ση(i) Abdomen | Ση(i) Total | Ση(i) Thorax/Ση(i) Abdomen |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.44 | 1.00 | 1.44 | 0.44 |

| 2 | 0.39 | 0.80 | 1.19 | 0.48 |

| 3 | 0.33 | 0.70 | 1.04 | 0.47 |

| 4 | 0.30 | 0.68 | 0.98 | 0.44 |

| 5 | 0.52 | 0.66 | 1.18 | 0.80 |

| 6 | 0.18 | 0.92 | 1.10 | 0.20 |

| 7 | 0.11 | 1.06 | 1.17 | 0.11 |

| 8 | 0.27 | 1.37 | 1.64 | 0.20 |

| 9 | 0.09 | 1.28 | 1.36 | 0.07 |

| 10 | 0.17 | 1.05 | 1.22 | 0.17 |

| 11 | 0.18 | 1.03 | 1.21 | 0.18 |

| 12 | 0.18 | 0.89 | 1.08 | 0.21 |

| 13 | 0.06 | 1.10 | 1.16 | 0.06 |

| 14 | 0.47 | 0.61 | 1.08 | 0.77 |

| 15 | 0.23 | 0.87 | 1.10 | 0.27 |

| Average | 0.26 | 0.93 | 1.20 | 0.32 |

| Stdev | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.24 |

Table 2.

Summary of the results for patients imaged only in the thorax. The values reported for Ση(i) Abdomen1 were estimated assuming Ση(i) Total = 1.11.

| Patient ID | Ση(i) Thorax | Ση(i) Abdomen1 | Ση(i) Thorax/Ση(i) Abdomen1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 0.28 | 0.83 | 0.34 |

| 17 | 0.24 | 0.87 | 0.28 |

| 18 | 0.04 | 1.07 | 0.04 |

| 19 | 0.13 | 0.98 | 0.13 |

| 20 | 0.16 | 0.95 | 0.17 |

| 21 | 0.25 | 0.86 | 0.29 |

| 22 | 0.41 | 0.70 | 0.58 |

| 23 | 0.22 | 0.89 | 0.25 |

| 24 | 0.37 | 0.74 | 0.50 |

| 25 | 0.12 | 0.99 | 0.12 |

| 26 | 0.12 | 0.99 | 0.13 |

| Average | 0.21 | 0.90 | 0.26 |

| Stdev | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.17 |

Estimated by assuming Ση(i) Total = 1.11.

Figure 4.

Distribution of Ση(i) for the thorax and abdominal regions for the whole body dataset and the thorax dataset (denoted with † subscript). The similarity between the thorax regions and the abdominal regions of both datasets is apparent.

DISCUSSION

The majority of body expansion occurred in the abdomen. The thorax-to-abdomen breathing ratio showed the thorax component was only 32% of the abdominal component. Therefore, placing a bellows on the abdominal region will typically provide greater sensitivity to respiratory motion than placing a bellows in the thorax region due to the greater body expansion in the abdomen. In this study, the bellows was placed in the same anatomical location in the abdominal region for each patient scanning session. The slice with the greatest expansion occurred between the third and fourth lumbar vertebrae for the 15 patients with whole body scans. Placing the bellows at that location would provide the greatest body surface expansion per breath and, correspondingly, the best measurement precision.

The fundamental value of the total volume to tidal volume expansion of the body (1.11) served as a useful metric for evaluating thoracic CT images. The measured value for the total volume to tidal volume expansion of the body was found to be 1.20 ± 0.17, which was only 7.2% higher than the expected ratio. This study measured the portion of this ratio in the thorax to be consistent between two groups, one with abdominal image data and one without.

CONCLUSION

A method to determine the relationship between abdomen and thoracic breathing was developed for breathing motion modeling and breathing motion studies. Two patient datasets containing CT information from the neck through the pelvis in one group and the thorax only in the second group were used in this study. The thorax and abdominal regions were statistically different in the first group, while the thorax regions were statistically similar between both groups. These results suggested that the thorax-to-abdomen expansion ratio was a fundamental property that could be used for breathing motion modeling and breathing motion studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01CA096679 and R01CA116712.

References

- Balter J. M. et al. , “Uncertainties in CT-based radiation therapy treatment planning associated with patient breathing,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 36(1), 167–174 (1996). 10.1016/S0360-3016(96)00275-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keall P. J. et al. , “Potential radiotherapy improvements with respiratory gating,” Australas. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 25(1), 1–6 (2002). 10.1007/BF03178368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S. et al. , “Impact of respiratory movement on the computed tomographic images of small lung tumors in three-dimensional (3D) radiotherapy,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 46(5), 1127–1133 (2000). 10.1016/S0360-3016(99)00352-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehmeh S. A. et al. , “Quantitation of respiratory motion during 4D-PET/CT acquisition,” Med. Phys. 31(6), 1333–1338 (2004). 10.1118/1.1739671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berbeco R. I. et al. , “A technique for respiratory-gated radiotherapy treatment verification with an EPID in cine mode,” Phys. Med. Biol. 50(16), 3669–3679 (2005). 10.1088/0031-9155/50/16/002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox T. et al. , “Free breathing gated delivery (FBGD) of lung radiation therapy: Analysis of factors affecting clinical patient throughput,” Lung Cancer 56(1), 69–75 (2007). 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehmeh S. A. et al. , “Effect of respiratory gating on reducing lung motion artifacts in PET imaging of lung cancer,” Med. Phys. 29(3), 366–3671 (2002). 10.1118/1.1448824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehmeh S. A. et al. , “A novel respiratory tracking system for smart-gated PET acquisition,” Med. Phys. 38(1), 531–538 (2011). 10.1118/1.3523100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T. et al. , “Application of the spirometer in respiratory gated radiotherapy,” Med. Phys. 30(12), 3165–3171 (2003). 10.1118/1.1625439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White B. M. et al. , “Investigation of a breathing surrogate prediction algorithm for prospective pulmonary gating,” Med. Phys. 38(3), 1587–1595 (2011). 10.1118/1.3556589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedam S. S. et al. , “Determining parameters for respiration-gated radiotherapy,” Med. Phys. 28(10), 2139–2146 (2001). 10.1118/1.1406524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agostoni E. et al. , “Forces deforming the rib cage,” Respir. Physiol. 2(1), 105–117 (1966). 10.1016/0034-5687(66)90042-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassino A. et al. , “Mechanics of the human diaphragm during voluntary contraction: Statics,” J. Appl. Physiol. 44(6), 829–839 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno K. and Mead J., “Measurement of the separate volume changes of rib cage and abdomen during breathing,” J. Appl. Physiol. 22(3), 407–422 (1967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead J. and Loring S. H., “Analysis of volume displacement and length changes of the diaphragm during breathing,” J. Appl. Physiol. 53(3), 750–755 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berbeco R. I. et al. , “Residual motion of lung tumours in gated radiotherapy with external respiratory surrogates,” Phys. Med. Biol. 50(16), 3655–3667 (2005). 10.1088/0031-9155/50/16/001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W. et al. , “Comparison of spirometry and abdominal height as four-dimensional computed tomography metrics in lung,” Med. Phys. 32(7), 2351–2357 (2005). 10.1118/1.1935776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W. et al. , “A comparison between amplitude sorting and phase-angle sorting using external respiratory measurement for 4D CT,” Med. Phys. 33(8), 2964–2974 (2006). 10.1118/1.2219772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W. et al. , “A semi-automatic method for peak and valley detection in free-breathing respiratory waveforms,” Med. Phys. 33(10), 3634–3636 (2006). 10.1118/1.2348764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low D. A. et al. , “A method for the reconstruction of four-dimensional synchronized CT scans acquired during free breathing,” Med. Phys. 30(6), 1254–1263 (2003). 10.1118/1.1576230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb J. M. et al. , “Generating lung tumor internal target volumes from 4D-PET maximum intensity projections,” Med. Phys. 38(10), 5732–5737 (2011). 10.1118/1.3633896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner R. et al. , “Technical note: Development of a tidal volume surrogate that replaces spirometry for physiological breathing monitoring in 4D CT,” Med. Phys. 37(2), 615–619 (2010). 10.1118/1.3284282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlastala M. P. and Berger A. J., Physiology of Respiration, 2nd ed. (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001), 275 pp. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary D., “Robust regression computation using iteratively reweighted least squares,” SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 11(3), 466–488 (1990). 10.1137/0611032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]