Abstract

Early-life exposures to brominated diphenyl ethers (BDEs) lead to neurobehavioral abnormalities later in life. Although these agents are thyroid disruptors, it is not clear whether this mechanism alone accounts for the adverse effects. We evaluated the impact of 2,2′,4,4′,5-pentabromodiphenyl ether (BDE99) on PC12 cells undergoing neurodifferentiation, contrasting the effects with chlorpyrifos, a known developmental neurotoxicant. BDE99 elicited decrements in the number of cells, evidenced by a reduction in DNA levels, to a lesser extent than did chlorpyrifos. This did not reflect cytotoxicity from oxidative stress, since cell enlargement, monitored by the total protein/DNA ratio, was not only unimpaired by BDE99, but was actually enhanced. Importantly, BDE99 impaired neurodifferentiation into both the dopamine and acetylcholine neurotransmitter phenotypes. The cholinergic phenotype was affected to a greater extent, so that neurotransmitter fate was diverted away from acetylcholine and toward dopamine. Chlorpyrifos produced the same imbalance, but through a different underlying mechanism, promoting dopaminergic development at the expense of cholinergic development. In our earlier work, we did not find these effects with BDE47, a BDE that has greater endocrine disrupting and cytotoxic effects than BDE99. Thus, our results point to interference with neurodifferentiation by specific BDE congeners, distinct from cytotoxic or endocrine mechanisms.

Keywords: Acetylcholine, BDE99, Brominated flame retardants, Dopamine, Neurodifferentiation, PC12 cells

INTRODUCTION

There is increasing concern over the adverse developmental effects of brominated diphenyl ethers (BDEs) used commonly as flame retardants, especially in light of their bioaccumulation and persistence (Branchi et al., 2003; Dingemans et al., 2011). Animal studies show conclusively that early-life exposure to these agents leads to persistent behavioral alterations in adulthood (Branchi et al., 2003; Viberg and Eriksson, 2011; Viberg et al., 2005); further, there is a significant correlation between prenatal BDE levels in maternal or cord blood and neurodevelopmental sequelae in children (Herbstman et al., 2010; Roze et al., 2009). Although a definitive mechanism has yet to be defined for the effects of BDEs on brain development, there are several prominent possibilities. First, these agents are known disruptors of thyroid function, including thyroid hormonal control of neurotrophic factors (Blanco et al., 2011; Branchi et al., 2005; Schreiber et al., 2010); thyroid disruption involves the same critical developmental stage over which brain development is vulnerable to BDEs (Eriksson et al., 2002). Second, the BDEs can evoke cytotoxicity via oxidative stress, both in vivo (Belles et al., 2010) and in vitro (Costa and Giordano, 2007; Huang et al., 2010). Third, they affect calcium fluxes and other cell signaling cascades that are essential both to neuronal function and development (Costa and Giordano, 2007; Dingemans et al., 2010a, b, 2011; Hendriks et al., 2010). Importantly, these effects are shared in varying degrees by multiple members of the BDE class.

In the current study, whether BDEs act directly to impair neurodifferentiation, irrespective of endocrine actions or shared properties as cytotoxic oxidative stressors. We focused on 2,2′,4,4′,5-penta-bromodiphenyl ether (BDE99), the congener most commonly found in human milk (Norén and Meironyté, 2000), specifically in contrast to our earlier work on 2,2′,4,4′-tetra-bromodiphenyl ether (BDE47) (Dishaw et al., 2011). These two BDEs share the mechanisms of endocrine disruption, oxidative stress leading to toxicity, and cell signaling effects, in each case with actions of BDE47 or its metabolites similar to, or more prominent than, those of BDE99 (Dingemans et al., 2010a, b, 2011; Hendriks et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2010; Schreiber et al., 2010; Tagliaferri et al., 2010).

Here, we show that BDE99 directly affects neurodifferentiation in PC12 cells, completely distinct from BDE47, which is ineffective in this model (Dishaw et al., 2011). The PC12 cell line is a well-characterized model for neurodifferentiation, and we used protocols established specifically for the screening of developmental neurotoxicants (Qiao et al., 2001, 2003 2005; Slotkin et al., 2007a, b, 2008; Song et al., 1998), in keeping with recommendations by the Inspector General of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2006). We evaluated indices of cell number, cell growth, neurite formation and differentiation into the dopaminergic (TH) and cholinergic (ChAT) phenotypes that are the distinctive fate of PC12 cells. To provide a perspective on the effects of BDE99, we included comparable measurements for chlorpyrifos, an organophosphate pesticide that is a known developmental neurotoxicant and that has been well-characterized in the PC12 cell line (Das and Barone, 1999; Dishaw et al., 2011; Lassiter et al., 2009; Qiao et al., 2005; Slotkin et al., 2007b; Slotkin and Seidler, 2010; Song et al., 1998).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultures

Because of the clonal instability of the PC12 cell line (Fujita et al., 1989), the experiments were performed on cells that had undergone fewer than five passages. As described previously (Qiao et al., 2003; Song et al., 1998), PC12 cells (American Type Culture Collection CRL-1721, obtained from the Duke Comprehensive Cancer Center, Durham, NC) were seeded onto poly-D-lysine-coated plates in RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% horse serum (Sigma), 5% fetal bovine serum (Sigma), and 50 μg/ml penicillin streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Incubations were carried out with 5% CO2 at 37°C, standard conditions for PC12 cells. To initiate neurodifferentiation (Jameson et al., 2006b; Slotkin et al., 2007b; Teng and Greene, 1994), the medium was changed to include 50 ng/ml of 2.5 S murine nerve growth factor (NGF; Promega Corporation, Madison, WI); each culture was examined under a microscope to verify the outgrowth of neurites after NGF treatment.

Toxicant exposures were all commenced simultaneously with the addition of NGF, so as to be present throughout neurodifferentiation. There were five different treatment groups (final concentrations shown): control, BDE99 (AccuStandard Inc, New Haven, CT) in concentrations of 10, 20 and 50 μM, and 50 μM chlorpyrifos (Chem Service, West Chester, PA). The medium was changed every 48 hr with the continued inclusion of NGF and each toxicant for a total exposure time of 6 days. Because of their limited water solubility, the test agents were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (Sigma; final concentration 0.1%), which was also added to the controls; this concentration of dimethylsulfoxide has no effect on PC12 cell growth or differentiation (Qiao et al., 2001; Song et al., 1998).

Assays

Cells were harvested, washed, and the DNA and protein fractions were isolated and analyzed as described previously (Slotkin et al., 2007b). Measurements of DNA, total protein and membrane protein were used as biomarkers for cell number, cell growth, and neurite growth (Qiao et al., 2003; Song et al., 1998). Neuronotypic cells contain a single nucleus, so that the DNA content per dish provides a measure of cell number (Winick and Noble, 1965). Since the DNA per cell is constant, cell growth entails an obligatory increase in the total protein per cell (protein/DNA ratio) as well as membrane protein per cell (membrane protein/DNA ratio). If cell growth represents simply an increase in the perikaryal area, then the ratio of membrane to total protein would fall in parallel with the decline in the surface-to-volume ratio (volume increases with the cube of the perikaryal radius, whereas surface area increases with the square of the radius); however, when neurites are formed as a consequence of neurodifferentiation, this produces a specific rise in the ratio. Each of these biomarkers has been validated in prior studies by direct measurement of cell number (Powers et al., 2010; Roy et al., 2005), perikaryal area (Roy et al., 2005) and neurite formation (Das and Barone, 1999; Howard et al., 2005; Song et al., 1998).

To assess neurodifferentiation into dopamine and acetylcholine phenotypes, we assayed the activities of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), respectively (Jameson et al., 2006a, b). TH activity was measured using [14C]tyrosine as a substrate and trapping the evolved 14CO2 after decarboxylation coupled to L-aromatic amino acid decarboxylase. Each assay contained 55 μM [1-14C]l-tyrosine (Moravek Biochemicals, Brea, CA; specific activity, 51 mCi/mmol, diluted to 3.3 mCi/mmol with unlabeled tyrosine) as substrate and activity was calculated as pmol synthesized per hour per μg DNA (i.e. activity per cell). ChAT assays were utilized a substrate of 50 μM [14C]acetyl-coenzyme A (specific activity 60 mCi/mmol; PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Waltham, MA). Labeled acetylcholine was extracted and activity calculated on the same basis as for TH.

Data analysis

All studies were performed using 3–5 separate batches of cells, with multiple independent cultures for each treatment in each batch; each batch of cells comprised a separately prepared, frozen and thawed passage. Results are presented as mean ± SE, with treatment comparisons carried out by ANOVA (data log-transformed when variance was heterogeneous), followed by Fisher’s Protected Least Significant Difference Test for post-hoc pairwise comparisons of individual treatments. First, we conducted a two-factor ANOVA (factors of treatment and cell batch) and found that the treatment effects were the same across the different batches of cells, although the absolute values differed from batch to batch. Accordingly, we normalized the results across batches prior to combining them for presentation. Significance was assumed at p < 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

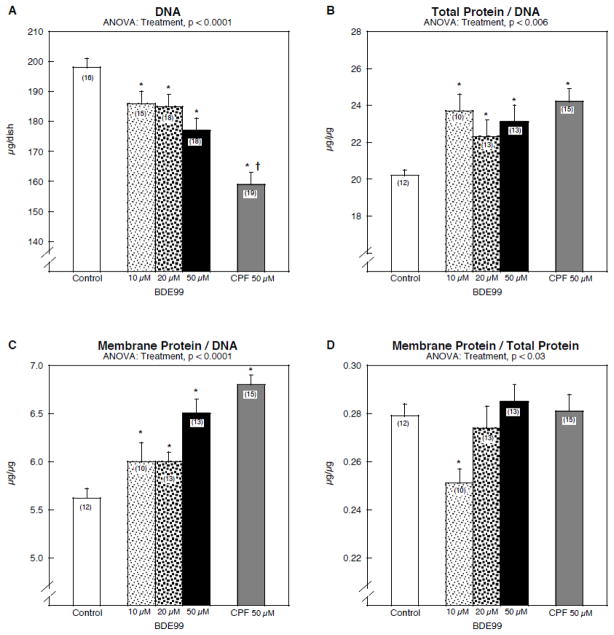

Exposure of differentiating PC12 cells to BDE99 produced a significant reduction in the number of cells, as evidenced by a decline in DNA content (Fig. 1A). The highest concentration of BDE99 (50 μM) was less deleterious than the same concentration of chlorpyrifos. The decline in DNA was not secondary to cytotoxicity, since cell growth was unimpaired by BDE99 (Fig. 1B); in fact, the total protein/DNA ratio was significantly increased at all concentrations, indicating that cell enlargement was occurring simultaneously with the reduction in cell numbers. For the growth parameter, even the lowest BDE99 concentration was as effective as 50 μM chlorpyrifos. Cell enlargement was further confirmed by measuring the membrane protein/DNA ratio (Fig. 1C). Again, all BDE99 concentrations produced a significant increment over the control value but in this case, only the highest concentration had effects that were comparable to those of chlorpyrifos. In turn, this implied that there were selective effects on membrane protein that were not shared by total protein. Since neurite formation is a major contributor to membrane protein, we then evaluated the membrane/total protein ratio. The lowest concentration of BDE99 suppressed this index, an effect that was lost at the higher concentrations; this effect was repeated in two entirely separate batches of cells conducted in independent experiments. A similar nonmonotonic relationship has been found previously for chlorpyrifos, which enhances the formation of dendritic neurites at the expense of longer-length projections at low concentrations, but suppresses neurite formation at higher concentrations (Axelrad et al., 2003; Das and Barone, 1999; Flaskos et al., 2011; Howard et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2008).

Figure 1.

Effects of BDE99 and chlorpyrifos (CPF) on cell growth parameters: (A) DNA concentration, (B) total protein/DNA ratio, (C) membrane protein/DNA ratio, (D) membrane protein/total protein. Data represent means and standard errors of the number of determinations in parentheses. ANOVA across all treatments is shown at the top of each panel and pairwise comparisons are shown within the panels by asterisks (significance difference vs. control) and daggers (significant difference between 50 μM chlorpyrifos and 50 μM BDE99). Abbreviation: CPF = chlorpyrifos.

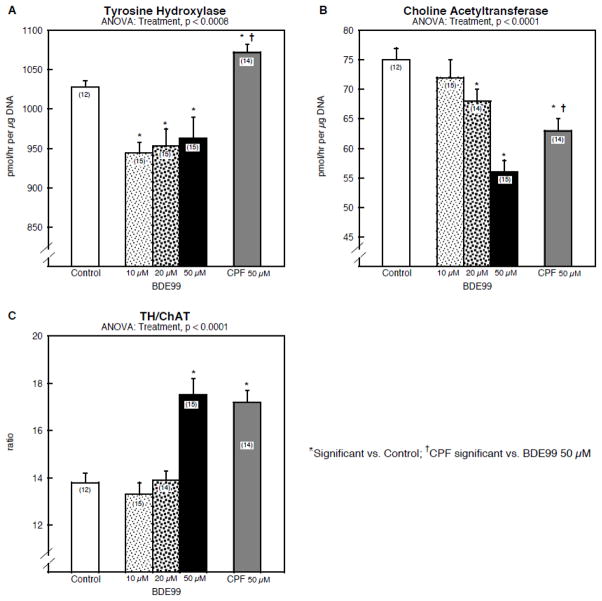

We then evaluated the effects of BDE99 on neurodifferentiation into the dopaminergic and cholinergic neurotransmitter phenotypes that are characteristic of PC12 cells. BDE99 suppressed the appearance of both TH (Fig. 2A) and ChAT (Fig. 2B) but again, the concentration-effect relationship was complex. For TH, the reduction was small, only 10%, but the effect was already maximal at the lowest BDE99 concentration. In contrast, the effect of ChAT showed a monotonic decline, eventually achieving a much larger effect, about a 30% decrement. Accordingly, at the highest concentration, there was a switch away from the cholinergic and toward the dopaminergic phenotype, as evidenced by an increase in the TH/ChAT ratio (Fig. 2C). The effects of BDE99 on TH were distinct from that of chlorpyrifos, which evoked an increase instead of a decrease (Fig. 2A), and BDE99 produced a larger decrement in ChAT than did chlorpyrifos at the same 50 μM concentration (Fig. 2B); consequently, both BDE99 and chlorpyrifos increased the TH/ChAT ratio (Fig. 2C), but from different underlying mechanisms.

Figure 2.

Effects of BDE99 and chlorpyrifos (CPF) on neurodifferentiation into dopaminergic and cholinergic phenotypes: (A) tyrosine hydroxylase activity (TH), (B) choline acetyltransferase activity (ChAT), (C) TH/ChAT ratio. Data represent means and standard errors of the number of determinations in parentheses. ANOVA across all treatments is shown at the top of each panel and pairwise comparisons are shown within the panels by asterisks (significance difference vs. control) and daggers (significant difference between 50 μM chlorpyrifos and 50 μM BDE99). Abbreviation: CPF = chlorpyrifos.

Our results indicate that BDE99 has two distinct effects on neurodifferentiation. It produces cell loss, not through cytotoxicity, but rather in association with promotion of cell growth, implying that it accelerates the transition from cell replication to cell enlargement that occurs early in neurodifferentiation (Song et al., 1998; Teng and Greene, 1994). At the same time, though, it suppresses key elements of neurodifferentiation in a complex manner. Neurite formation is reduced at low concentrations only, indicating a nonmonotonic response curve resembling that of the organophosphates. Perhaps more importantly, BDE99 suppresses the emergence of neurotransmitter phenotypes, with different concentration effects for dopamine vs. acetylcholine. The fact that the cholinergic phenotype eventually shows the largest deficits is entirely in keeping with the neurobehavioral effects of this flame retardant after early-life exposures in vivo, which likewise show strong cholinergic components (Fischer et al., 2008; Viberg et al., 2005). Equally important, in our earlier work, we showed that BDE47 was ineffective against cell numbers, growth or neurodifferentiation in this model (Dishaw et al., 2011), so the effects of BDE99 cannot reflect their shared properties as thyroid disruptors or oxidative stressors. Indeed, the pattern of effects seen here for BDE99 also differ from those associated with known oxidative stressors in the PC12 model (Lassiter et al., 2009; Qiao et al., 2005; Slotkin et al., 2007b; Slotkin and Seidler, 2010). Accordingly, the present findings point to the likelihood that BDE99 acts as a developmental neurotoxicant by targeting neurodifferentiation directly in neuronal cells, independently of its other potential actions or on endocrine or other systemic effects. Since these effects are not shared by BDE47, manipulating specific structural characteristics of BDEs could enable the design of congeners with less propensity to disrupt nervous system development.

Highlights.

BDE99 reduced cell numbers while enhancing cell growth in PC12 cells

BDE99 impaired neurodifferentiation into acetylcholine and dopamine phenotypes

Effects were not shared by BDE47, which is a greater endocrine disruptor

Specific BDE congeners directly interfere with neurodifferentiation

Acknowledgments

Research was supported by NIH ES010356.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- BDE

brominated diphenyl ether

- BDE47

2,2′,4,4′-tetra-bromodiphenyl ether

- BDE99

2,2′,4,4′,5-penta-bromodiphenyl ether

- ChAT

choline acetyltransferase

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: TAS has provided expert witness testimony in the past three years at the behest of the following law firms: The Calwell Practice (Charleston WV), Finnegan Henderson Farabow Garrett & Dunner (Washington DC), Carter Law (Peoria IL), Gutglass Erickson Bonville & Larson (Madison WI), The Killino Firm (Philadelphia PA), Alexander Hawes (San Jose, CA), Pardieck Law (Seymour, IN), Tummel & Casso (Edinburg, TX) and the Shanahan Law Group (Raleigh NC).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Axelrad JC, Howard CV, McLean WG. The effects of acute pesticide exposure on neuroblastoma cells chronically exposed to diazinon. Toxicology. 2003;185:67–78. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00592-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belles M, Alonso V, Linares V, Albina ML, Sirvent JJ, Domingo JL, et al. Behavioral effects and oxidative status in brain regions of adult rats exposed to BDE-99. Toxicol Lett. 2010;194:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco J, Mulero M, Lopez M, Domingo JL, Sanchez DJ. BDE-99 deregulates BDNF, Bcl-2 and the mRNA expression of thyroid receptor isoforms in rat cerebellar granular neurons. Toxicology. 2011;290:305–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branchi I, Capone F, Alleva E, Costa LG. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers: neurobehavioral effects following developmental exposure. Neurotoxicology. 2003;24:449–62. doi: 10.1016/S0161-813X(03)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branchi I, Capone F, Vitalone A, Madia F, Santucci D, Alleva E, et al. Early developmental exposure to BDE 99 or Aroclor 1254 affects neurobehavioural profile: interference from the administration route. Neurotoxicology. 2005;26:183–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa LG, Giordano G. Developmental neurotoxicity of polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE) flame retardants. Neurotoxicology. 2007;28:1047–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das KP, Barone S. Neuronal differentiation in PC12 cells is inhibited by chlorpyrifos and its metabolites: is acetylcholinesterase inhibition the site of action? Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1999;160:217–30. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingemans MML, Heusinkveld HJ, Bergman Å, van den Berg M, Westerink RHS. Bromination pattern of hydroxylated metabolites of BDE-47 affects their potency to release calcium from intracellular stores in PC12 cells. Environ Health Perspect. 2010a;118:519–25. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingemans MML, van den Berg M, Bergman Å, Westerink RHS. Calcium-related processes involved in the inhibition of depolarization-evoked calcium increase by hydroxylated PBDEs in PC12 cells. Toxicol Sci. 2010b doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp310. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingemans MML, van den Berg M, Westerink RHS. Neurotoxicity of brominated flame retardants: (in)direct effects of parent and hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers on the (developing) nervous system. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:900–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishaw LV, Powers CM, Ryde IT, Roberts SC, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA, et al. Is the PentaBDE replacement, tris (1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate (TDCPP), a developmental neurotoxicant? Studies in PC12 cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011;256:281–9. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson P, Viberg H, Jakobsson E, Orn U, Fredriksson A. A brominated flame retardant, 2,2′,4,4′,5-pentabromodiphenyl ether: uptake, retention, and induction of neurobehavioral alterations in mice during a critical phase of neonatal brain development. Toxicol Sci. 2002;67:98–103. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/67.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer C, Fredriksson A, Eriksson P. Coexposure of neonatal mice to a flame retardant PBDE 99 (2,2′,4,4′,5-pentabromodiphenyl ether) and methyl mercury enhances developmental neurotoxic defects. Toxicol Sci. 2008;101:275–85. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaskos J, Nikolaidis E, Harris W, Sachana M, Hargreaves AJ. Effects of sub-lethal neurite outgrowth inhibitory concentrations of chlorpyrifos oxon on cytoskeletal proteins and acetylcholinesterase in differentiating N2a cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011;256:330–6. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita K, Lazarovici P, Guroff G. Regulation of the differentiation of PC12 pheochromocytoma cells. Environ Health Perspect. 1989;80:127–42. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8980127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks HS, Antunes Fernandes EC, Bergman A, van den Berg M, Westerink RHS. PCB-47, PBDE-47, and 6-OH-PBDE-47 differentially modulate human GABAA and α4 β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Toxicol Sci. 2010;118:635–42. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbstman JB, Sjodin A, Kurzon M, Lederman SA, Jones RS, Rauh V, et al. Prenatal exposure to PBDEs and neurodevelopment. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:712–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard AS, Bucelli R, Jett DA, Bruun D, Yang DR. Chlorpyrifos exerts opposing effects on axonal and dendritic growth in primary neuronal cultures. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;207:112–24. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SC, Giordano G, Costa LG. Comparative cytotoxicity and intracellular accumulation of five polybrominated diphenyl ether congeners in mouse cerebellar granule neurons. Toxicol Sci. 2010;114:124–32. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameson RR, Seidler FJ, Qiao D, Slotkin TA. Adverse neurodevelopmental effects of dexamethasone modeled in PC12 cells: identifying the critical stages and concentration thresholds for the targeting of cell acquisition, differentiation and viability. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006a;31:1647–58. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameson RR, Seidler FJ, Qiao D, Slotkin TA. Chlorpyrifos affects phenotypic outcomes in a model of mammalian neurodevelopment: critical stages targeting differentiation in PC12 cells. Environ Health Perspect. 2006b;114:667–72. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassiter TL, MacKillop EA, Ryde IT, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Is fipronil safer than chlorpyrifos? Comparative developmental neurotoxicity modeled in PC12 cells. Brain Res Bull. 2009;78:313–22. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norén K, Meironyté D. Certain organochlorine and organobromine contaminants in Swedish human milk in perspective of past 20–30 years. Chemosphere. 2000;40:1111–23. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(99)00360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers CM, Wrench N, Ryde IT, Smith AM, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Silver impairs neurodevelopment: studies in PC12 cells. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:73–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao D, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Developmental neurotoxicity of chlorpyrifos modeled in vitro: comparative effects of metabolites and other cholinesterase inhibitors on DNA synthesis in PC12 and C6 cells. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:909–13. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao D, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Oxidative mechanisms contributing to the developmental neurotoxicity of nicotine and chlorpyrifos. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;206:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao D, Seidler FJ, Violin JD, Slotkin TA. Nicotine is a developmental neurotoxicant and neuroprotectant: stage-selective inhibition of DNA synthesis coincident with shielding from effects of chlorpyrifos. Dev Brain Res. 2003;147:183–90. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(03)00222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy TS, Sharma V, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Quantitative morphological assessment reveals neuronal and glial deficits in hippocampus after a brief subtoxic exposure to chlorpyrifos in neonatal rats. Dev Brain Res. 2005;155:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roze E, Meijer L, Bakker A, Van Braeckel KNJA, Sauer PJJ, Bos AF. Prenatal exposure to organohalogens, including brominated flame retardants, influences motor, cognitive, and behavioral performance at school age. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:1953–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber T, Gassmann K, Götz C, Huubenthal U, Moors M, Krause G, et al. Polybrominated diphenylethers induce developmental neurotoxicity in a human in vitro model: evidence for endocrine disruption. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:572–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, MacKillop EA, Melnick RL, Thayer KA, Seidler FJ. Developmental neurotoxicity of perfluorinated chemicals modeled in vitro. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:716–22. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, MacKillop EA, Ryde IT, Seidler FJ. Ameliorating the developmental neurotoxicity of chlorpyrifos: a mechanisms-based approach in PC12 cells. Environ Health Perspect. 2007a;115:1306–13. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, MacKillop EA, Ryde IT, Tate CA, Seidler FJ. Screening for developmental neurotoxicity using PC12 cells: comparisons of organophosphates with a carbamate, an organochlorine and divalent nickel. Environ Health Perspect. 2007b;115:93–101. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Seidler FJ. Oxidative stress from diverse developmental neurotoxicants: antioxidants protect against lipid peroxidation without preventing cell loss. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2010;32:124–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Violin JD, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Modeling the developmental neurotoxicity of chlorpyrifos in vitro: macromolecule synthesis in PC12 cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998;151:182–91. doi: 10.1006/taap.1998.8424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliaferri S, Caglieri A, Goldoni M, Pinelli S, Alinovi R, Poli D, et al. Low concentrations of the brominated flame retardants BDE-47 and BDE-99 induce synergistic oxidative stress-mediated neurotoxicity in human neuroblastoma cells. Toxicol in Vitro. 2010;24:116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng KK, Greene LA. Cultured PC12 cells: a model for neuronal function and differentiation. In: Celis JE, editor. Cell Biology: A Laboratory Handbook. San Diego: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 218–24. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Opportunities to Improve Data Quality and Children’s Health Through the Food Quality Protection Act. 2006. Report no. 2006-P-00009. Vol., ed.^eds. [Google Scholar]

- Viberg H, Eriksson P. Differences in neonatal neurotoxicity of brominated flame retardants, PBDE 99 and TBBPA, in mice. Toxicology. 2011;289:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viberg H, Fredriksson A, Eriksson P. Deranged spontaneous behaviour and decrease in cholinergic muscarinic receptors in hippocampus in the adult rat, after neonatal exposure to the brominated flame-retardant, 2,2′,4,4′,5-pentabromodiphenyl ether (PBDE99) Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2005;20:283–8. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winick M, Noble A. Quantitative changes in DNA, RNA and protein during prenatal and postnatal growth in the rat. Dev Biol. 1965;12:451–66. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(65)90009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Howard A, Bruun D, Ajua-Alemanj M, Pickart C, Lein PJ. Chlorpyrifos and chlorpyrifos-oxon inhibit axonal growth by interfering with the morphogenic activity of acetylcholinesterase. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;228:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]