Abstract

We examined fear, avoidance and physiological symptoms during cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for social anxiety disorder (SAD). Participants were 177 individuals with generalized SAD who underwent a 14-week group CBT as part of a randomized controlled treatment trial. Participants filled out self-report measures of SAD symptoms at pre-treatment, week 4 of treatment, week 8 of treatment, and week 14 of treatment (post-treatment). Cross-lagged Structural Equation Modeling indicated that during the first 8 weeks of treatment avoidance predicted subsequent fear above and beyond previous fear, but fear did not predict subsequent avoidance beyond previous avoidance. However, during the last 6 weeks of treatment both fear and avoidance predicted changes in each other. In addition, changes in physiological symptoms occurred independently of changes in fear and avoidance. Our findings suggest that changes in avoidance spark the cycle of change in treatment of SAD, but the cycle may continue to maintain itself through reciprocal relationships between avoidance and fear. In addition, physiological symptoms may change through distinct processes that are independent from those involved in changes of fear and avoidance.

Keywords: social anxiety disorder, cognitive-behavior therapy, fear, avoidance, physiological symptoms, expectancy

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is a common and debilitating psychiatric disorder with an estimated lifetime prevalence rate of 12.1% (Kessler et al., 2005). SAD is characterized by a fear of social interactions (e.g., talking to a stranger or peer, going to a party) and performance situations (e.g., giving a speech), behavioral avoidance of these situations, and physiological arousal (e.g., racing heart, sweating, trembling). Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment (CBT) is effective in reducing SAD symptoms (Acarturk, Cuijpers, van Straten, & de Graaf, 2009; Rodebaugh, Holaway, & Heimberg, 2004) and so are certain pharmacological therapies (Blanco et al., 2003; Hedges, Brown, Shwalb, Godfrey, & Larcher, 2007).

Although the efficacy of CBT for SAD is well established (e.g., Fedoroff & Taylor, 2001), the processes of change during treatment are not well understood. Some studies have examined cognitive mediators of treatment change (Hofmann, 2004), and some have examined the mediational relationship between social anxiety and depression during treatment (Moscovitch, Hofmann, Suvak, & In-Albon, 2005), but to date, no study has examined the interrelationships between fear, avoidance and physiological symptoms of social anxiety along the course of treatment. This is important as it can shed light on processes of symptom change and can inform our theoretical models of SAD, as well as the most effective targets for therapeutic intervention.

Current CBT models of SAD stress that avoidance plays a key role in the development and maintenance of the disorder (Clark, 2005; Clark & Wells, 1995; Hofmann, 2007; Rapee & Heimberg, 1997). Avoidance of stressful situations thwarts opportunities for inhibitory learning by blocking access to information that is incompatible with fear-related cognitions (Alden & Wallace, 1991; Hofmann, 2004; McManus, Clark, & Hackmann, 2000; Moscovitch, 2009; Wallace & Alden, 1995, 1997). Similarly, safety behaviors (sometimes referred to as subtle avoidance behaviors) have been found to maintain SAD symptoms (e.g., McManus, Sacadura, & Clark, 2008), and reductions in safety behaviors have been associated with reduced anxiety, and reduced negative cognitions (Kim, 2005; Morgan & Raffle, 1999; Stangier, Heidenreich, & Schermelleh-Engel, 2006; Taylor & Alden, 2010; Wells et al., 1995). Consistent with the causal role of avoidance behaviors in maintaining SAD, a chief objective of CBT is to target avoidance behaviors through exposure techniques, in order to reduce SAD-related fear (e.g., Clark, 2005).

The relationship between physiological symptoms on the one hand and avoidance and social fears on the other is less clear. It is possible that reductions in physiological symptoms would lead to reductions in social fears, as many individuals with SAD fear exhibiting physiological symptoms (e.g., “I will blush”). Conversely, it is possible that reduced fear would lead to reduced physiological symptoms because individuals experience lower levels of arousal in social situations. It is also possible that reductions in physiological symptoms would lead to reductions in avoidance of social situations, as social situations become less threatening when physiological symptoms are less salient. Maintenance models of SAD have not explicitly delineated the temporal relationships between physiological symptoms and fear and avoidance (Clark, 2005; Clark & Wells, 1995; Hofmann, 2007; Rapee & Heimberg, 1997). Thus, it remains unclear whether changes in physiological symptoms affect avoidance or fear, are affected by avoidance or fear, or both. Understanding this relationship is important as it can shed light on mechanisms of change during treatment and can help us understand whether targeting physiological symptoms can augment current treatments.

In the present study, our aims were three-fold. First, we wanted to examine the relationship between avoidance and fear during a full-length course of CBT. The vast majority of studies examining avoidance and safety behaviors have used one-session experiments in which participants conduct a single exposure and are measured on SAD symptoms before and after the session. Thus, we wanted to build on these studies and extend the examination of the avoidance-fear relationship to treatment settings. We hypothesized that based on previous findings from single-session experiments (e.g., Kim, 2005; McManus et al., 2009; Wells et al., 1995), avoidance would affect subsequent fear (but not vice-versa). Second, we wanted to explore the relationship between physiological symptoms on the one hand and avoidance and fear on the other. This second aim was exploratory because maintenance models of SAD and previous research have not focused on the temporal relationship between physiological symptoms and avoidance and fear. Third, as some researchers suggest that common treatment factors (e.g., insight, therapeutic alliance, treatment expectancy) play a large role in determining treatment outcome (Messer & Wampold, 2002), we examined one such factor - treatment expectancy - and its relationship to treatment outcome.

We hypothesized that fear, avoidance, and physiological symptoms would be correlated at each assessment point during treatment (synchronous effects). This is because all three are symptom clusters of social anxiety disorder. We also hypothesized that for each symptom cluster, symptom levels at each assessment point would predict symptom levels at the next assessment point (stability effects; e.g., fear at measurement t would predict fear at measurement t + 1). In addition, we hypothesized that avoidance at each assessment point would predict fear at the next assessment point (cross-lagged effects; avoidance at time t would predict fear at time t +1). Finally, based on a previous study in SAD (Safren, Heimberg, & Juster, 1997) we hypothesized that treatment expectancy would predict treatment outcome.

Method

Participants

The sample included 177 individuals with generalized SAD who participated in a two-site, randomized controlled trial (Davidson et al., 2004). Only participants randomized to CBT were included in the present study (CBT alone, n = 59; CBT and Placebo, n = 59; CBT and Fluoxetine, n = 59). Of the total sample, 85 (48.3%) were females. The mean age was 37.6 (SD = 10.0), and mean years of education were 14.7 (SD = 3.5). Most participants were Caucasian (77.1%), with the next largest group being African American (16.6%), followed by Asian (3.4%), Hispanic (2.3%), and Other (0.6%). There were no differences between treatment conditions on any of the demographic variable (all ps > .05). In addition, there were no differences between treatment conditions in terms of treatment outcome as measured by the Brief Social Phobia Scale (Davidson et al., 2004). The initial severity of SAD symptoms as measured by the Brief Social Phobia Scale was 38.74 (SD = 9.98).

Inclusion criteria for the trial were: (1) DSM-IV diagnosis of generalized SAD; (2) age between 18 and 65 years; (3) fluency in English. Exclusion criteria were: (1) a primary anxiety disorder other than SAD (defined by which disorder was the more debilitating and clinically salient); (2) lifetime history of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or organic brain syndrome; (3) major depression within the last 6 months; (4) substance abuse or dependence within the past year; (5) mental retardation or pervasive developmental disability; (6) unstable medical condition; (7) prior failure of response to fluoxetine at 60 mg/d for at least 4 weeks or to 12 weekly sessions of CBT for GSP; (8) concurrent psychiatric treatment or other psychoactive medications; (9) positive urine drug screen results; (10) inability to maintain 2 weeks’ psychotropic drug-free washout; and (11) pregnancy or lactation.

Procedure

Following informed consent, participants were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM - IV (First & Gibbon, 2004). In addition, participants underwent psychiatric and medical evaluation to establish inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of 722 individuals initially assessed for eligibility, 173 (24%) did not meet inclusion criteria and were excluded from study participation. Participants were randomized to one of the treatment conditions using a computer program. Participants were assessed at pre-treatment, as well as at week 4, week 8, and week 14 of treatment (post-treatment) by independent evaluators, blind to treatment conditions. Thirty-five participants (19.8%) dropped out of the study during treatment. Of these, 10 dropped out before week 4, 20 dropped out between week 4 and 8, and 5 dropped out between week 8 and 14.

Treatments

Comprehensive Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

This treatment was a 14-week group treatment comprised of exposure exercises, cognitive restructuring, and social skills training. Each group included 5–6 participants, and two trained therapists (one male and one female) . The first 2 sessions were psychoeducational, and included information regarding the CBT model of SAD and the rationale for treatment. Session 3 and 4 were devoted to social skills training, and included role-plays structured to teach social skills such as initiating and ending conversations, and negotiating. Session 5 to 13 included individualized role-plays tailored to participants’ social fears. In addition cognitive restructuring was conducted before and after the role plays. Session 14 included a discussion of treatment gains and recommendations for future practices. For additional details, see Davidson and colleagues (Davidson et al., 2004).

Fluoxetine

Fluoxetine was started at 10 mg/d, and was increased by 10 mg increments after one week, two weeks, and four weeks. Thus, unless adverse effects became problematic, the goal was for subjects to reach 40 mg/d. If this target dose did not produce significant improvement (defined as a score of 1 or 2 on the Clinical Global Impressions Improvement scale; Guy, 1976), the dose was raised to 50 mg/d and 60 mg/d at weeks 6 and 8, respectively. For additional details regarding the pharmacological treatment, see Davidson and colleagues (Davidson et al., 2004).

Measures

The Brief Social Phobia Scale (BSPS; Davidson et al., 1991; Davidson, Miner, De Veaugh-Geiss, Tupler, & Potts, 1997)

The BSPS is a clinician administered measure that consists of 18 items. The BSPS assesses 7 situations commonly feared or avoided by individuals with SAD, with fear and avoidance of these situations coded separately. In addition, the BSPS assesses the extent of 4 physiological reactions to social anxiety, including blushing, heart palpitations, tremors, and sweating. Thus, the BSPS has 3 subscales: fear, avoidance and physiological arousal. The BSPS has high inter-rater reliability, as well as test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and construct validity (BSPS; Davidson et al., 1991; Davidson et al., 1997). It is also sensitive to pharmacotherapy (Davidson et al., 1997; Davidson, Tupler, & Potts, 1994), and was found to be more sensitive to drug-placebo effects compared to other measures (Davidson et al., 1997). In the present study, treatment resulted in large changes in all subscales of the BSPS (dfear = 1.56; davoidance = 1.54; dphysiological = 1.11).

The Reaction to Treatment Questionnaire (RTQ; Holt & Heimberg, 1990)

This measure includes four items developed by Borkovec and Nau (1972) that assess the credibility of treatment rationales (e.g., “How logical does this type of treatment seem to you?”) and nine additional items that assess clients’ confidence that treatment will eliminate their anxiety in specific social situations (e.g., being introduced). Items are scored on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all logical or confident) to 10 (very logical or confident), producing a total score with a possible range of 13–130. This measure has been used to assess the effect of expectancy on CBT outcome among individuals with SAD (Safren et al., 1997). This measure was administered once at session 4.

Missing Data and Analytic Strategy

We examined if data were missing at random using Little’s Missing-Completely-At-Random (MCAR) test (Little & Rubin, 1989). This test examines if missing data appear randomly (H0) or non-randomly (H1) throughout the measurements. A non-significant result indicates that data are missing completely at random (Little & Rubin, 1989; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2004). We then used Bayesian multiple imputation (Rubin, 1987; Rubin, 1996) to handle missing data. Compared with other imputation methods, multiple imputation is suitable for longitudinal data (e.g., for within-subjects or time-series data), and it retains sampling variability (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2004). Rubin (1996) has shown that 3–5 imputations can be adequate to perform statistical analysis. In the present study we chose a more stringent approach and conducted 10 imputations.

To examine the relationship between fear, avoidance, and physiological symptoms during the course of treatment we conducted cross-lagged, structural equation modeling (SEM). Specifically, we estimated synchronous effects (i.e., correlations between anxiety, avoidance, and physiological symptoms at each time point), stability effects (i.e., effects of a symptom cluster at time t on the same cluster at time t +1), and cross-lagged effects (i.e., the effect of a symptom cluster at time t on the other clusters at time t +1). All analyses were conducted using Mplus (version 7). Because some of the variables were non-normally distributed, we used Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2 statistics throughout the results (Satorra & Bentler, 1998, 2001). Model fit was assessed using the following fit indices: the Storra-Bentler scaled χ2 index, the Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI; Bentler & Bonett, 1980, labeled the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) in AMOS), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Steiger, 1980). Models are said to fit the data well when the χ2 is non-significant, the NNFI and CFI are > 0.90 (Bentler, 1990), and the RMSEA is < 0.06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 1998).

To examine whether the identified model differed between the three treatment conditions, we used a three-step approach. First, we measured model fit when all pathways were constrained to equality for the three groups. Second, we measured model fit when pathways were allowed to differ between the three groups. Third, as the first model is nested within the second one (i.e., a special case of the second model in which all pathways are identical between groups), we compared the models using the Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2 difference test. A non-significant difference would indicate that allowing the pathways to differ does not result in better model fit. This would suggest that the more parsimonious, constrained model is the better model. A significant difference would indicate that allowing the pathways to differ results in better model fit, and that significant differences exist between the groups regarding the model pathways.

Results

Missing Data

Our sample included 177 individuals with fear, avoidance, and physiological symptoms measured at four time-points during treatment. Thus the total data set included 2124 data points with 336 (15.8%) containing missing data. These data were missing completely at random (Little’s MCAR test χ2 = 58.60, df = 69, p = 0.81, n.s.). Missing data were imputed using Bayesian multiple imputation, and all analyses were conducted on the imputed data set.

SEM Analyses

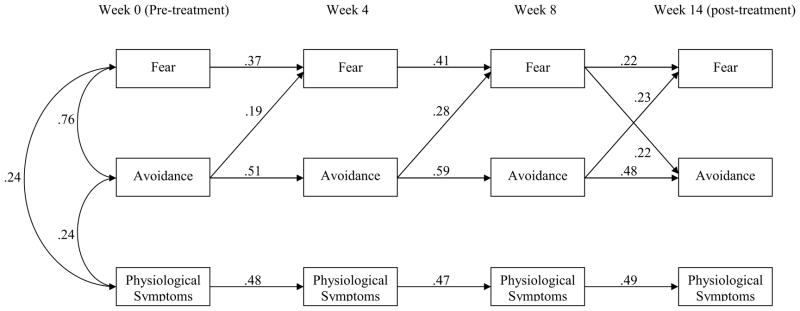

Table 1 presents the correlation matrix between all variables in the model, as well as means and standard deviations. We estimated a model with all synchronous effects, stability effects, and cross-lagged effects. This model had a good fit with the data (Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2 = 39.49, df = 27, p = 0.06; TLI = 0.97; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.05). In the next step, we removed all non-significant pathways according to the procedures outlined by Bentler and Moojaart (1989). The resulting model included all synchronous effects and stability effects, as well as the cross-lagged pathways between avoidance at pre-treatment and fear at week 4 (β = 0.19, SE = 0.06, p < 0.05), avoidance at week 4 and fear at week 8 (β = 0.28, S = 0.05, E p < 0.001), avoidance at week 8 and fear at week 14 (β = 0.23, S = 0.06, E p < 0.001), and fear at week 8 and avoidance at week 14 (β = 0.22, S = 0.10, E p < 0.01). This model had an excellent fit with the data (Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2 = 52.61, df = 41, p = 0.11; TLI = 0.98; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.04). This final model is presented in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Correlation matrix between all variables in the model

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Fear0 | - | |||||||||||

| 2. Fear4 | 0.53*** | - | ||||||||||

| 3. Fear8 | 0.43*** | 0.62*** | - | |||||||||

| 4. Fear14 | 0.35*** | 0.44*** | 0.75*** | - | ||||||||

| 5. Avoid0 | 0.76*** | 0.48*** | 0.41*** | 0.35*** | - | |||||||

| 6. Avoid4 | 0.42*** | 0.69*** | 0.56*** | 0.43*** | 0.51*** | - | ||||||

| 7. Avoid8 | 0.26*** | 0.44*** | 0.71*** | 0.65*** | 0.37*** | 0.59*** | - | |||||

| 8. Avoid14 | 0.21** | 0.37*** | 0.59*** | 0.81*** | 0.29*** | 0.44*** | 0.66*** | - | ||||

| 9. Phys0 | 0.24** | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.24** | 0.16* | 0.02 | 0.01 | - | |||

| 10. Phys4 | 0.11 | 0.21** | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.24** | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.47*** | - | ||

| 11. Phys8 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.31*** | 0.28*** | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.32*** | 0.28*** | 0.34*** | 0.47*** | - | |

| 12. Phys14 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.31*** | 0.41*** | 0.11 | 0.24** | 0.31*** | 0.44*** | 0.19* | 0.32*** | 0.51*** | - |

| M | 16.52 | 14.85 | 12.28 | 10.01 | 15.84 | 13.21 | 10.46 | 8.09 | 6.35 | 4.87 | 3.31 | 2.93 |

| SD | 4.17 | 3.78 | 3.95 | 4.30 | 5.02 | 5.41 | 4.65 | 5.14 | 3.09 | 2.89 | 2.40 | 2.66 |

Note. Fear = Fear subscale of the Brief Social Phobia Scale; Avoid = Avoidance subscale of the Brief Social Phobia Scale; Phys = Psychophysiological symptoms subscale of the Brief Social Phobia Scale; 0 = week 0 (pre-treatment); 4 = week 4; 8 = week 8; 14 = week 14 (post-treatment).

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

Figure 1.

Final SEM model

Note. Numbers represent regression weights (β) and pertain to statistically significant parameters. Synchronous effects (i.e. correlations between subscales at a given time point) are not presented for weeks 4, 8, and 14 for purposes of clarity. Correlations at week 4 are 0.61, 0.20 and 0.23 (for fear-avoidance, avoidance-physiological symptoms, and fear- physiological symptoms respectively). Correlations at week 8 are 0.60, 0.37 and 0.36 (for fear-avoidance, avoidance-physiological symptoms, and fear- physiological symptoms respectively). Correlations at week 14 are 0.66, 0.31 and 0.26 (for fear-avoidance, avoidance-physiological symptoms, and fear- physiological symptoms respectively).

We also examined whether this model held for all three treatment conditions. When all pathways were constrained to equality across the conditions, the resulting Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2 was 217.49 (df = 173, p < 0.01). When the pathways were allowed to differ between conditions, the Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2 was 155.09 (df = 123, p < 0.05). The Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2 difference was 62.41 (df = 50) which is below the critical value of 67.51. This indicates that the difference between models is non-significant and that allowing the pathways to vary does not result in a better fitting model. Therefore, the final model has a similar fit in all conditions.

Synchronous Effects

We compared synchronous effects at each time point using Meng, Rosenthal, and Rubin’s (1992) formula. We found that at each time point, fear-avoidance correlations (r = 0.60 to 0.76) were significantly greater than correlations between fear and physiological symptoms (r = 0.23 to 0.36), and correlations between avoidance and physiological symptoms (r = 0.20 to 0.37; all ps < 0.05).

Mediation

We examined whether the effect of avoidance at week 4 on avoidance at week 14 was mediated by fear at week 8. We followed the guidelines of Preacher and Hayes (2004) and conducted the mediation analysis using a bootstrapping procedure (5000 samples). We found evidence of a significant indirect effect (95% confidence interval = 0.18 to 0.35) indicating that fear significantly mediated the relationship between avoidance at week 4 and avoidance at week 14. The index of mediation (Preacher & Hayes, 2008, Preacher & Kelley, 2011), a standardized effect size for the indirect effect, was 0.28, indicating that avoidance at week 14 increases by 0.28 standard deviations for every 1 SD increase in avoidance at week 4 indirectly through fear at week 8.

Expectancy

We examined whether expectancy ratings predicted post-treatment BSPS scores while controlling for pretreatment BSPS scores using regression analyses. We found no significant relationship between expectancy ratings and post-treatment SAD severity (β = −0.11, t = −1.18, p = 0.24). Similarly, no significant relationship was found between expectancy ratings and improvement during treatment (β = −0.11, t = −1.53 p = 0.13).

Discussion

The present study examined the inter-relationships between fear, avoidance, and physiological symptoms during CBT for SAD. To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal evaluation of the relationship among symptoms clusters in SAD. We found significant synchronous effects at all assessment points indicating that fear, avoidance, and physiological symptoms were associated throughout treatment. We also found stability effects indicating that each symptom cluster could be predicted in part by previous levels of that cluster. Finally, we found several significant cross-lagged effects. In the first 8 weeks of treatment, avoidance predicted subsequent fear above and beyond previous levels of fear. However, fear did not predict subsequent avoidance above and beyond previous levels of avoidance, indicating a unidirectional relationship between avoidance and fear. During the last 6 weeks of treatment, both avoidance and fear predicted each other, indicating a reciprocal relationship. No cross-lagged effects were found for physiological symptoms, indicating that these symptoms do not predict fear or avoidance, nor are predicted by fear and avoidance. Thus, physiological symptoms may change independently from both fear and avoidance.

The synchronous effects found in the present study suggest that fear, avoidance, and physiological symptoms are related symptom clusters of SAD. However, during treatment the associations between fear and avoidance were stronger (r = 0.60 to 0.76) compared to the associations between fear and physiological symptoms (r = 0.23 to 0.36) or avoidance and physiological symptoms (r = 0.20 to 0.37). This suggests that fear and avoidance are more closely linked compared to their associations with physiological symptoms. This is consistent with DSM-IV criteria for SAD which stress the importance of fear and avoidance (but not physiological symptoms), as defining aspects of the disorder. Thus, physiological symptoms may be related to SAD but less central to the disorder.

Moreover, we found no evidence that perceptions of physiological symptoms in treatment for SAD are related to changes in fear or avoidance. Thus, changes in physiological symptoms may occur independently of fear and avoidance. This is in contrast to the relationship found in other anxiety disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In PTSD, hyperarousal and physiological symptoms were found to play a prominent role in predicting later avoidance and fear (Schell, Marshall, & Jaycox, 2004). Our findings suggest that in social anxiety disorder, the role of perceptions of physiological symptoms may be less pronounced and that routinely augmenting cognitive-behavioral treatments by targeting perceptions of physiological symptoms may not result in added reductions in fear and avoidance. However, these findings are preliminary and more research needs to be done in order to draw firm conclusions. Controlled trials in which participants are randomized to conditions that either directly target or do not target physiological symptoms may further extend our knowledge regarding the role of physiological symptoms in the disorder.

A second explanation for the independence of physiological symptoms from fear and avoidance is related to measurement issues. In the present study, we measured self-reported physiological symptoms. There is evidence that ratings of some physiological symptoms such as blushing differ substantially between self-report and physiological measurement (Gerlach, Wilhelm, Gruber, & Roth, 2001; Mulkens, de Jong, Dobbelaar, & Bögels, 1999). Thus, it is possible that a different pattern of results would have emerged had we measured physiological symptoms using a different methodology. However, it is also important to note that CBT and cognitive models focus on the role of perceptions of physiological symptoms rather than actual physiological symptoms in maintaining the disorder, suggesting that self-report measurement may be better suited for capturing this maintaining factor. Future studies can use additional measures of physiological symptoms to increase our understanding of the role of actual and perceived physiological symptoms in CBT.

A third potential explanation for the independence of physiological symptoms from fear and avoidance is that our sample consisted of individuals with a diagnosis of generalized SAD. As mentioned above, physiological symptoms may not be central to the generalized form of the disorder. However, it is possible that certain subgroups of individuals with SAD may exhibit a different relationship. For instance, individuals with a primary fear of blushing (Voncken & Bögels, 2009), or sweating or trembling (Bögels, 2006) may show a different pattern of results, as these individuals’ fears are focused on physiological symptoms. Indeed, fear of blushing, sweating or trembling has been proposed as a distinct subtype of SAD for consideration in DSM-V (Bögels et al., 2010). Future studies should examine the relationship between fear, avoidance, and physiological symptoms among individuals with primary physiological concerns. In addition, future studies can examine specific physiological symptoms (e.g., sweating vs. blushing) in order to understand weather certain symptoms respond differently to treatment or interact differently with fear and avoidance during treatment. For instance, blushing and palpitations have been found to be more responsive to Sertraline compared to trembling and sweating (Connor, Davidson, Chung, Yang, & Clary, 2006).

The relationship between fear and avoidance found in the present study suggests that consistent with cognitive-behavioral models of SAD (Clark, 2005; Clark & Wells, 1995; Hofmann, 2007; Rapee & Heimberg, 1997), reductions in avoidance lead to reductions in fear along the course of CBT. Our findings are also in line with single-session experiments that examined the impact of avoidance behaviors on fear (e.g., Kim, 2005; McManus et al., 2009; Wells et al., 1995). In these studies, avoidance behaviors were manipulated and their affects on subsequent anxiety and fear were examined. The present findings extend this body of knowledge as they suggest that the same relationship between avoidance and fear is found along the course of cognitive-behavioral treatment of SAD.

There are several mediators that can account for the relationship between avoidance and fear during CBT. These include but are not limited to behavioral mechanisms such as habituation (Eckman & Shean, 1997), cognitive mechanisms such as hypothesis testing (Clark, 2005), and affective mechanisms such as reductions in experiential avoidance (Kashdan, Breen, Afram, & Terhar, 2010). Future studies can examine these potential mediators of the relationship between avoidance and fear during treatment.

The present findings provide support for targeting avoidance early in treatment. This is consistent with cognitive treatments for SAD which include interventions for targeting avoidance as early as session 2 (e.g., the “safety behaviors experiment”; Clark et al., 2006; Clark et al., 2003). Treatments that include such interventions report very high effect sizes (2.14 in Clark et al. 2003, and 2.63 in Clark et al. 2006) and have been shown to be superior to treatments that do not include an emphasis on subtle avoidance behaviors (Rapee, Gaston, & Abbott, 2009). In addition to these previous outcome-focused studies, the present findings contribute to this literature by providing process-focused evidence that avoidance influences changes in fear during CBT for SAD.

We also found that reductions in fear can lead to reductions in avoidance as well, and that a reciprocal relationship develops between the two in the late stages of treatment. Thus it may be changes in avoidance that spark the cycle of change in treatment of SAD, but the cycle may continue to maintain itself through reciprocal relationships between avoidance and fear. It is possible that this reciprocal relationship that develops is essential for long-term maintenance of gains in CBT for SAD. Along these lines, we found that fear mediated the relationship between avoidance at week 4 and avoidance at post-treatment, suggesting that avoidance affects fear which in turn affects subsequent avoidance. However, much more research needs to be done in order to establish the relationship between avoidance and fear in the treatment of SAD. Despite the preliminary nature of these findings, the present study provides novel evidence for reciprocal relations that may develop in the later stages of treatment. Future studies can examine this relationship in various treatments for SAD.

In contrast to a previous study in SAD (Safren et al., 1997), we did not find treatment expectancy to predict treatment outcome. However, in that study only 1–4% of the variance in self-report SAD measures was accounted for by expectancy. Therefore it is possible that we could not detect this effect in our sample due to its small effect size. In addition, our data suggest that a specific process (exposure; reduction in avoidance) led to greater symptom improvement while a non-specific process was unrelated to outcome. Thus, models that suggest that common factors are more important than techniques may be too general. It is more likely that common factors such as motivation, expectancy, and the alliance interact with techniques, helping individuals to avoid less, and therefore fear less. It is likely that improvement in symptoms via these techniques then improves the common factors in a transactional way.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, our sample included only individuals with generalized SAD. It is possible that the relationship between the symptom clusters would not generalize to individuals with non-generalized SAD or individuals whose fears are focused primarily on physiological symptoms. Second, the symptom clusters examined in the present study were derived from a single self-report measure: the BSPS. Future studies should include several measures of SAD to ensure that results are consistent across measures.

Despite these limitations, the present study represents the first study to examine the interrelationship between symptom clusters of SAD during CBT. Examining interrelationships between symptom clusters can shed light on processes of treatment change as well as targets for interventions. Our findings point to the prominent role of avoidance in predicting changes in fear along the course of treatment, but also to reciprocal relations between avoidance and fear that may develop in the later stages of treatment.

We examined fear, avoidance and physiological symptoms during CBT for SAD

During the first 8 weeks of CBT, avoidance predicted changes in fear but not vice versa

During the last 6 weeks of CBT, both avoidance and fear predicted changes in each other

Physiological symptoms were unrelated to changes in fear and avoidance

Avoidance may spark the process of change in CBT for SAD

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acarturk C, Cuijpers P, van Straten A, de Graaf R. Psychological treatment of social anxiety disorder: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine: A Journal of Research in Psychiatry and the Allied Sciences. 2009;39:241–254. doi: 10.1017/s0033291708003590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alden LE, Wallace ST. Social standards and social withdrawal. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1991;15:85–100. doi: 10.1007/bf01172944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indices in structural equation models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structure. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Moojaart A. Choice of structural equation models via parsimony: a rational based on precision. Psychological Bulletin. 1989;106:315–317. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.106.2.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Schneier FR, Schmidt A, Blanco-Jerez C-R, Marshall RD, Sánchez-Lacay A, et al. Pharmacological treatment of social anxiety disorder: A meta-analysis. Depression and Anxiety. 2003;18:29–40. doi: 10.1002/da.10096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels SM. Task concentration training versus applied relaxation, in combination with cognitive therapy, for social phobia patients with fear of blushing, trembling, and sweating. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1199–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels SM, Alden L, Beidel DC, Clark LA, Pine DS, Stein MB, et al. Social anxiety disorder: Questions and answers for the DSM-V. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27:168–189. doi: 10.1002/da.20670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1972;3:257–260. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(72)90045-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM. The essential handbook of social anxiety for clinicians. New York, NY, US: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2005. A Cognitive Perspective on Social Phobia; pp. 193–218. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Ehlers A, Hackmann A, McManus F, Fennell M, Grey N, et al. Cognitive therapy versus exposure and applied relaxation in social phobia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:568–578. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.74.3.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Ehlers A, McManus F, Hackmann A, Fennell M, Campbell H, et al. Cognitive Therapy Versus Fluoxetine in Generalized Social Phobia: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:1058–1067. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.6.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Wells A. Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1995. A cognitive model of social phobia; pp. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Connor KM, Davidson JRT, Chung H, Yang R, Clary CM. Multidimensional effects of sertraline in social anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2006;23:6–10. doi: 10.1002/da.20086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JRT, Foa EB, Huppert JD, Keefe FJ, Franklin ME, Compton JS, et al. Fluoxetine, comprehensive cognitive behavioral therapy, and placebo in generalized social phobia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:1005–1013. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JRT, Miner CM, De Veaugh-Geiss J, Tupler LACJT, Potts NL. The Brief Social Phobia Scale: A psychometric evaluation. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:161–166. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JR, Potts NL, Richichi EA, Ford SM, Krishnan RR, Smith RD, et al. The Brief Social Phobia Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1991;52:48–51. doi: 10.1037/t07672-000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JRT, Tupler LA, Potts NLS. Treatment of social phobia with benzodiazepines. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1994;55:28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckman PS, Shean GD. Habituation of cognitive and physiological arousal and social anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:1113–1121. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(97)80005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedoroff IC, Taylor S. Psychological and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;21:311–324. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200106000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M. Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment, Vol. 2: Personality assessment. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2004. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II) pp. 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach AL, Wilhelm FH, Gruber K, Roth WT. Blushing and physiological arousability in social phobia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:247–258. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.110.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, Revised. Rockville: 1976. pp. 76–338. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges DW, Brown BL, Shwalb DA, Godfrey K, Larcher AM. The efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in adult social anxiety disorder: A meta-analysis of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2007;21:102–111. doi: 10.1177/0269881106065102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG. Cognitive Mediation of Treatment Change in Social Phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:392–399. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.72.3.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG. Cognitive factors that maintain social anxiety disorder: A comprehensive model and its treatment implications. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2007;36:195–209. doi: 10.1080/16506070701421313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CS, Heimberg RG. The Reaction to Treatment Questionnaire: Measuring treatment credibility and outcome expectancies. The Behavior Therapist. 1990;13:213–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Breen WE, Afram A, Terhar D. Experiential avoidance in idiographic, autobiographical memories: Construct validity and links to social anxiety, depressive, and anger symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E-J. The effect of the decreased safety behaviors on anxiety and negative thoughts in social phobics. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2005;19:69–86. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. The Analysis of Social Science Data with Missing Values. Sociological Methods & Research. 1989;18:292–326. doi: 10.1177/0049124189018002004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McManus F, Clark DM, Grey N, Wild J, Hirsch C, Fennell M, et al. A demonstration of the efficacy of two of the components of cognitive therapy for social phobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus F, Clark DM, Hackmann A. Specificity of cognitive biases in social phobia and their role in recovery. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2000;28:201–209. doi: 10.1017/s1352465800003015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McManus F, Sacadura C, Clark DM. Why social anxiety persists: An experimental investigation of the role of safety behaviours as a maintaining factor. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2008;39:147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X-l, Rosenthal R, Rubin DB. Comparing correlated correlation coefficients. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:172–175. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Messer SB, Wampold BE. Let’s face facts: Common factors are more potent than specific therapy ingredients. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9:21–25. doi: 10.1093/clipsy/9.1.21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan H, Raffle C. Does reducing safety behaviors improve treatment response in patients with social phobia? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;33:503–510. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.1999.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitch DA. What Is the Core Fear in Social Phobia? A New Model to Facilitate Individualized Case Conceptualization and Treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2009;16:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitch DA, Hofmann SG, Suvak MK, In-Albon T. Mediation of changes in anxiety and depression during treatment of social phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:945–952. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.73.5.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkens S, de Jong PJ, Dobbelaar A, Bögels SM. Fear of blushing: fearful preoccupation irrespective of facial coloration. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1999;37:1119–1128. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. In: Hayes AF, Slater MD, Snyder LB, editors. The Sage sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. pp. 13–54. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Kelley K. Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods. 2011;16:93–115. doi: 10.1037/a0022658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Gaston JE, Abbott MJ. Testing the efficacy of theoretically derived improvements in the treatment of social phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:317–327. doi: 10.1037/a0014800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Heimberg RG. A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:741–756. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodebaugh TL, Holaway RM, Heimberg RG. The treatment of social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:883–908. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: J. Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation After 18+ Years. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91:473–489. [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Heimberg RG, Juster HR. Clients’ expectancies and their relationship to pretreatment symptomatology and outcome of cognitive-behavioral group treatment for social phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:694–698. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.65.4.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. Scaling corrections for chi-square statistics in covariance structure analysis. Proceedings of the American Statistical Association. 1998:308–313. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66:507–514. doi: 10.1007/s11336-009-9135-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell TL, Marshall GN, Jaycox LH. All Symptoms Are Not Created Equal: The Prominent Role of Hyperarousal in the Natural Course of Posttraumatic Psychological Distress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:189–197. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.113.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stangier U, Heidenreich T, Schermelleh-Engel K. Safety behaviors and social performance in patients with generalized social phobia. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2006;20:17–31. doi: 10.1891/jcop.20.1.17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH. Test for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;87:245–251. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5. Boston: Pearson Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CT, Alden LE. Safety behaviors and judgmental biases in social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48:226–237. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voncken MJ, Bögels SM. Physiological blushing in social anxiety disorder patients with and without blushing complaints: Two subtypes? Biological Psychology. 2009;81:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace ST, Alden LE. Social anxiety and standard setting following social success or failure. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1995;19:613–631. doi: 10.1007/bf02227857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace ST, Alden LE. Social phobia and positive social events: The price of success. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:416–424. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.106.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells A, Clark DM, Salkovskis P, Ludgate J, Hackmann A, Gelder M. Social phobia: The role of in-situation safety behaviors in maintaining anxiety and negative beliefs. Behavior Therapy. 1995;26:153–161. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(05)80088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]