Abstract

Purpose:

To determine the prevalence of patient refusal of glaucoma surgery (GSR) and the associated factors in Lagos, Nigeria.

Materials and Methods:

A multicenter cross-sectional survey was conducted in Lagos state, Nigeria. Twelve centres were invited to participate, but data collection was completed in 10. Newly diagnosed glaucoma patients were recruited and interviewed from these sites over a four week period on prior awareness of glaucoma, surgery refusal, and reason(s) for the refusal. Presenting visual acuity was recorded from the patient files. The odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated.

Results:

A total of 208 newly diagnosed glaucoma patients were recruited. Sixty–five (31.2%) patients refused surgery. Fear of surgery (31 (47.7%) patients), and fear of going blind (19 (29.2%) patients) were the most common reasons. The odds ratio of surgery refusal were marital status – not married versus married (2.0; 95% CI, 1.02–3.94), use of traditional medication – users versus non users (2.4; 95% CI, 1.1–5.2), perception of glaucoma causing blindness – no versus yes (3.7; 95% CI, 1.3–10.5), type of institution - government versus private (5.7; 95% CI, 1.3–25.1), and visual acuity in the better eye - normal vision versus visual impairment (2.3; 95% CI, 1.1–4.9). Age, gender, level of education, family history of glaucoma, and prior awareness of the diagnosis of glaucoma, were not significantly associated with surgery refusal. Perception of patients concerning glaucoma blindness was the strongest factor on multivariate analysis.

Conclusion:

GSR was relatively low in this study. Unmarried status, use of traditional medications, perception that glaucoma cannot cause blindness, government hospital patients, and good vision in the better eye were associated with GSR. These factors might help in the clinical setting in identifying appropriate individuals for targeted counseling, as well as the need for increased public awareness about glaucoma.

Keywords: Blindness, Glaucoma, Nigeria, Surgery Refusal, Visual Impairment

INTRODUCTION

The only modifiable risk factor in glaucoma management is reduction of intraocular pressure (IOP),1 and this has been shown,2–4 to be effective in preventing or slowing the deterioration of visual function. This can be achieved medically, with the use of laser treatment or surgically.

Surgery has been recommended as the primary treatment for glaucoma in Africa,5–7 mainly because of the challenges of continuous medical treatment, such as affordability, availability, and compliance. Despite this recommendation, rates of glaucoma surgery remain low8 in Nigeria. One of the contributing factors is the low rate of acceptance of glaucoma surgery among eligible patients. Quigley et al.,9 found an acceptance rate of 46% in Tanzania, while Omoti et al.,10 found an acceptance rate of 32.5% in Benin City, Nigeria, a south-eastern part of the country.

Among other factors, patients may be reluctant to accept glaucoma surgery because there is no visual improvement postoperatively. An understanding of the possible factors associated with refusal of glaucoma surgery from the perspective of the patient, might enable providers to work towards reducing these barriers and ultimately lead to better uptake. Furthermore, studies on factors affecting the acceptance of glaucoma surgery are sparse in the literature. Therefore, this study was conducted to determine the prevalence of patient refusal of glaucoma surgery and the associated factors in Lagos, Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area and sites

Lagos State is the economic and commercial centre of Nigeria, with all the ethnic and geopolitical groups in Nigeria represented in this state.11 There are two tertiary (government owned) institutions and 24 secondary level (government owned) hospitals;12 but only nine of the secondary hospitals had functioning eye units at the time of the study. There are about 50 private eye clinics, most of which are single ophthalmologist practices. The institutions invited for participation in this study were the nine secondary centres, the two tertiary centres, and one large private hospital. Two secondary centers did not participate. Private single ophthalmologist practices were not included in this study. Government hospitals were chosen as primary sites of study based on the assumption that the government is the largest provider of health (including eye care) to the majority of the population,13 and that the institutions are fairly well distributed across the state.14

Data collection

Information was collected over a four week period (July 2010) with a specially designed and pre-tested questionnaire. The questionnaire was pretested on two of study sites. The questionnaire was administered by trained research assistants (RA) stationed at the participating institutions on all newly diagnosed glaucoma patients who underwent a face-to face interview. Ophthalmologists, resident doctors, and medical officers in all the study sites had been informed to direct all newly diagnosed glaucoma patients to the designated RA throughout the study period. The designated RA also issued reminders to attending ophthalmologists and resident doctors on each clinic day to ensure all newly diagnosed glaucoma patients were recruited. The criteria for patient selection were a diagnosis of glaucoma by the attending doctor. Data collected included socio-demographic characteristics, the presenting complaint, information on prior awareness of glaucoma, and acceptance of surgery. Basic examination findings were retrieved from the patient charts.

Data management

Data were entered and analyzed with Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), and Stata /IC 11.0 (StataCorp, LP, College Station, Texas, USA). Frequency tables were generated for variables and tests of statistical significance between variables were performed with the Chi square and Fisher's exact test (when variables counts were less than 5). A p value of less than 0.05 was statistically significant.

Ethical clearance and approvals

Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethics committee of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom, and Lagos State University Teaching Hospital (LASUTH), Lagos State, Nigeria. Approvals were also obtained from the Lagos State Health Service Commission, and from each participating hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in this study.

RESULTS

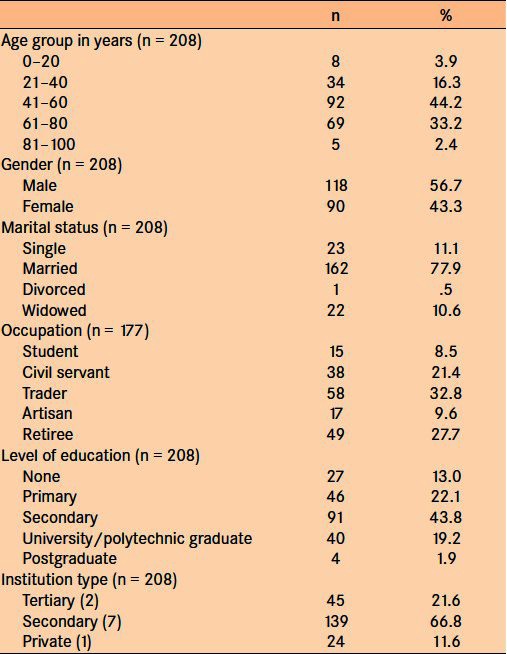

A total of 208 newly diagnosed glaucoma cases were recruited during the study period. There were 118 (56.7%) males. The mean age was 54.2 ± 16.4 years. The youngest patient was 17 years and the oldest was 87 years. The most common age group was 41–60 years. There were 109 (79.0%) patients older than 40 years. Other sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of new glaucoma patients

Presentation

The majority of patients (107 (77.5%) patients) presented with poor vision in one or both eyes. Other ocular complains included itching, ache, redness, inability to read small letters, and heaviness of the eyes. There were 135 (64.9%) patients who presented within one year of noticing symptoms, 32 (15.4%) within 2–3 years, 19 (9.1%) within 4–5 years, and 22 (10.6%) after 5 years of onset of symptoms. Eighty-five (40.9%) patients had visited at least one other eye centre prior to presenting again to the study site, while 20 (9.6%) had visited two or more eye hospitals. Thirty-one (14.9%) patients admitted to using some form of traditional eye medications/remedies (TEM) due to ocular symptom(s), and types of TEM used included local herbs, coconut water, urine, holy water, and couching.

Fifty-five (26.4%) patients gave a history of glaucoma in at least one family member and 43 (78.2%) of these patients were first degree relatives. Ninety-four (45.2%) patients had not heard of the glaucoma prior to this study. Among those who knew about glaucoma (114 patients), sources of information included, hospitals for 57 (50.0%) patients, friends, and relatives for 45 (39.5%) patients, radio, and television for 9 (7.9%) patients, and other sources for 3 (2.6%) patients.

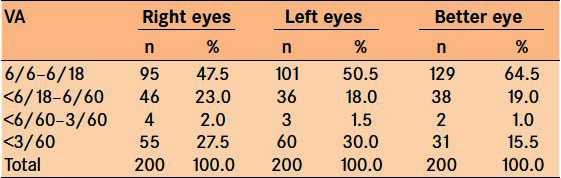

Presenting visual acuity (VA) is presented in Table 2. Only 200 (96.2%) patients had complete documentation of their visual acuity. Thirty-one (15.5%) patients were blind (VA in the better eye less than 3/60) at presentation and 84 (42.0%) had monocular blindness.

Table 2.

Presenting visual acuity (VA)

Seventy patients (33.7%) were already aware of their glaucoma diagnosis, but they presented as new glaucoma cases to the study site during the study period. There was no statistically significant difference between those aware of their diagnosis and those unaware in terms of age, gender, marital status, type of institution, and VA in the better eye (p > 0.05, all cases). Those that were aware of their diagnosis were more likely to have attained secondary level education and higher (OR 3.8, 95% CI; 1.8–8.5), and visited at least one hospital prior to the study (OR 3.6, 95% CI; 1.9–7.0).

Eight-five (40.9%) patients believed that glaucoma cannot cause vision loss, while 86 (41.4%) patients believed visual loss from glaucoma can be regained with treatment. Eighty-four (40.4%) patients were aware of the familial nature of glaucoma.

Glaucoma surgery acceptance / refusal

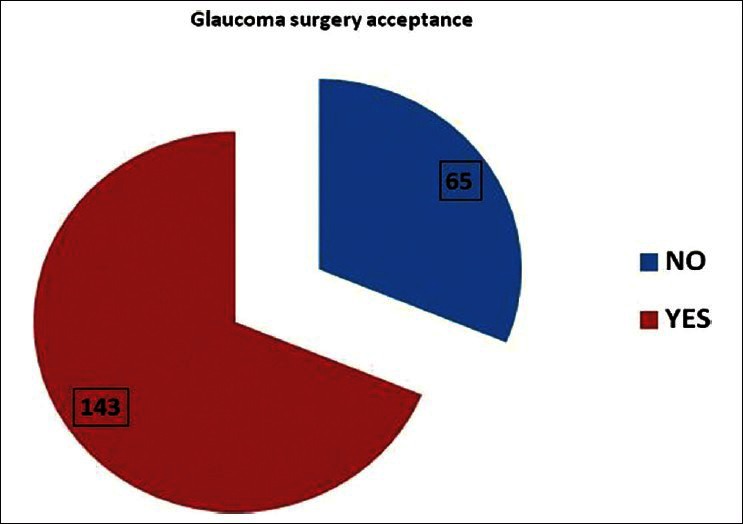

The proportion of patients willing to accept surgery is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Glaucoma surgery acceptance among patients (n = 208)

Sixty-five patients refused surgery. Reasons for refusal of surgery included fear of surgery (31 (47.7%) patients), fear of going blind (19 (29.2%), high cost of surgery (8 (12.3%), no improvement in vision (6 (9.2%) patients), and religious belief (1 (1.5%) patients). The association between patient characteristics and acceptance of surgery is presented in Table 3.

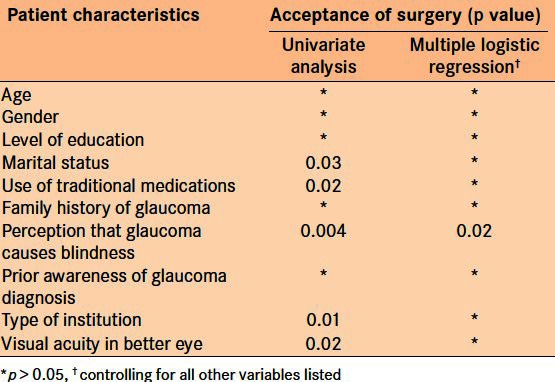

Table 3.

Association between patient characteristics and acceptance of glaucoma surgery

Using univariate analysis, factors significantly associated with acceptance of surgery were marital status, history of traditional medication use, perception of glaucoma causing blindness, type of institution, and visual acuity in the better eye. The odds ratio of surgery refusal were marital status - not married versus married (2.0; 95% CI: 1.02–3.94); use of traditional medication - users versus non users (2.4; 95% CI, 1.1–5.2); perception of glaucoma causing blindness - no versus yes (3.7; 95% CI, 1.3–10.5); type of institution - government versus private (5.7; 95% CI, 1.3–25.1); and visual acuity in the better eye - normal vision versus visual impairment (2.3; 95% CI, 1.1–4.9).

Only perception of glaucoma causing blindness and history of use of traditional eye medications were significantly associated after adjusting for other variables.

DISCUSSION

Glaucoma is a chronic and blinding eye disease for which early detection and effective treatment are potential strategies for controlling the progressive nature of this disease. Once a diagnosis of glaucoma has been made, the treatment is to lower the intraocular pressure to such a level sufficient enough to prevent further damage to the optic nerve head. This can be achieved by using medical treatment, laser surgery or incisional surgery. Medical treatment of glaucoma is challenging, and fraught with a lot of factors affecting compliance, such as availability and affordability of genuine products, and so on. This is more so in resource poor settings such as Africa where the majority of the populace is poor. Hence, surgery has been advocated as the primary treatment for glaucoma patients in Africa.5,7 However, there is some evidence to suggest that glaucoma surgical rates are low and may be declining in some African regions. This situation may be surgeon or patient related. Due to the challenges of postoperative management, some surgeons may be reluctant to offer surgical treatment modality for glaucoma. Patient related factors include refusal of surgery, even when offered.

This study found that over two thirds (68.8%) of the patients were willing to accept surgery as a treatment option. This is a relatively high proportion compared with 8.2% found by Adegbehingbe8 in Ile-Ife, Nigeria; 32.5% by Omoti et al.,10 in Benin city, Nigeria; 46.8% by Onyekwe et al.,15 in Onitsha, Nigeria, and 48% by Mafwiri et al.,16 in Tanzania. The high acceptance rate in this study might be related to the verbal consent method of assessing acceptance, and not whether the patient actually returned for surgery. This is because some patients might initially accept undergoing surgery, but later reconsider. However, the opposite may also occur, those that initially refused surgery, might also reconsider their decision later. Another factor is the method of interview, which was face to face interview in this study. This might have also created a response bias, as some patients may not want to be seen by health care providers as being unwilling to accept a proposed treatment method. These factors might have overestimated the surgery acceptance rate in this study.

However, we believe that this high response signifies a positive attitude towards surgery acceptance in this group of patients. The possible advantages of this include an increase in the glaucoma surgical output, improved skill and techniques in glaucoma surgeries as a result of performing more surgeries, increased opportunities for trainee ophthalmologists to learn, and ultimately better outcomes for glaucoma patients. There is also the potential for well designed and executed research methods into the different surgical techniques for glaucoma surgery in this environment, something which is quite rare.

Fear of surgery itself was the most common (47.7% patients) reason for refusal of surgery. This was followed by fear of going blind (29.2% patients), the high cost of surgery (12.3% patients), lack of visual improvement post operatively (9.2% patients), and religious beliefs (1.5% patients). This is in contrast to barriers to the uptake of cataract surgical services, where cost is the number one factor.17

Univariate analysis indicated factors that were significantly associated with acceptance of surgery were; marital status, history of use of traditional medications, perception of glaucoma causing blindness, type of institution, and visual acuity in the better eye (p < 0.05, all cases). Age, gender, level of education, prior awareness of the diagnosis of glaucoma, and family history of glaucoma were not significantly associated (p > 0.05).

Unmarried patients were found to be twice as likely to refuse surgery (OR 2.0; 95% CI: 1.02–3.94) compared to married patients. The increased probability of married patients toward surgery acceptance may be related to availability of greater support structure for the married patients, especially the perception of a need for adequate postoperative care, which a spouse will readily provide.

Traditional eye medications/remedies (TEM) are the various herbal and non-herbal concoctions and practices, prescribed by traditional and lay people18,19 – for example friends and relatives – for the prevention and management of ocular diseases.20 Thirty-one (14.9%) patients admitted to using some form of TEM on account of their ocular symptom(s) Various types of TEM used included; local herbs, coconut water, urine, holy water, and even couching. Evaluation TEM use, Eze et al.18 found a prevalence of 5.9% in South-Western Nigeria, while Mutombo found a prevalence of 17.9% in Democratic Republic of Congo,19 among all newly presenting patients to ophthalmic outpatient centres. Apart from direct physical effects when instilled in the eye, harmful TEMs have the potential of causing delays in seeking appropriate eye care when patients develop ocular symptoms. In this study, users of TEM were found to be more than twice as likely to refuse surgery (2.4; 95% CI, 1.1–5.2), compared with non users, and this association remained significant (though borderline) even after adjusting for other variables such as age, gender, level of education and visual acuity in the better eye [Table 3]. This may be related to the trust that these patients have in TEM, and its potential capability to alleviate their symptoms, thereby, causing delay in accepting appropriate therapy. Possible clinical application of this result is that patients with a history of use of TEM may be targeted for intensive counselling towards surgery acceptance.

The patient's understanding of any disease in terms of causes, treatment modalities, complications, and prognosis have great implications for the successful management of the disease. Adequate patient understanding has been shown to affect compliance with medical treatment of glaucoma.21 In this study, patients with the perception that “glaucoma is incapable of causing visual loss,” were almost four times more likely to refuse surgery (OR 3.7; 95% CI: 1.3–10.5), and this was the only factor that remained significant after adjusting for other variables. Practically, in the clinic setting, patients may be questioned about this to identify those likely to refuse surgery. Patients visiting a government institution were also found to be more likely to refuse surgery (OR 5.7; 95% CI, 1.3–25.1) compared with private hospital patients. This may be due to the less personalised care and perhaps less time to conduct effective counselling in the government setting.

Visual acuity in the better eye was found to be significantly associated with refusal of surgery in this study. We found that those with normal vision were more likely to refuse surgery (OR 2.3; 95% CI, 1.1–4.9), compared with those who had visual impairment. This is similar to findings by Quigley et al.,9 in their study among glaucoma patients detected during a population based survey in rural Tanzania, where those who agreed to surgery had slightly worse acuity in the better eye, though this was not statistically significant. This may not be surprising as those with relatively normal vision might fear visual loss from surgery, while those with poor vision might think they have more to gain from surgery. This might be an encouraging factor for surgeons who are somewhat reluctant to operate on patients with advanced glaucoma with poor vision.

In terms of other variables such as age, gender, level of education, family history of glaucoma, and prior awareness of the diagnosis of glaucoma, those who accepted surgery and those who refused were not significantly different from each other. This is similar to findings by Quigley et al.,9 who found that age and gender profiles did not significantly differ between the two groups.

These are some limitations of this study. The inability to include all the private eye care facilities in the state due to logistic constraints of the study might indicate a less generalizable result. However, government institutions were chosen as the primary sites because they are the largest provider of health care, including eye care, in this community,22 and the study sites were fairly evenly distributed within the state. Also, the lack of uniform criteria for diagnosis for the newly recruited patients who were interviewed is another limitation. In this study, in the criteria for inclusion in the study was a diagnosis of glaucoma by the attending consultant ophthalmologist or senior registrar. This might have resulted in some selection bias. However, this criteria was used make allow the easier enrolment and conduct of the study, as well as capture the perceived burden of glaucoma at each study centre. Additionally, all the ophthalmologists were trained in Nigeria, therefore, the criteria for the diagnosis of glaucoma is likely to be similar. Despite these limitations, we believe this study presents important contributions into the understanding of glaucoma surgery acceptance in Lagos, Nigeria.

In conclusion, a significant proportion of newly diagnosed glaucoma patients in Lagos state were willing to accept surgery as a treatment modality, and factors associated with refusal of surgery were; marital status, history of TEM use, perception of glaucoma causing blindness, type of institution, and visual acuity in the better eye. Perception of glaucoma causing blindness was found to be the strongest predictor of refusal of surgery. These factors might help in the clinical setting in identifying appropriate individuals for targeted counselling, as well as the need for increased public awareness of glaucoma, especially the progressive and irreversible nature of glaucoma related blindness.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Commonwealth Scholarship Commission (CSC) on behalf of the British Government, the British Council for the Prevention of Blindness (BCPB) through the Boulter Fellowship Scheme, ORBIS UK, and the Allan and Nesta Ferguson Foundation

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Racette L, Wilson MR, Zangwill LM, Weinreb RN, Sample PA. Primary open-angle glaucoma in blacks: A review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:295–313. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(03)00028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Normal Tension Glaucoma Study Group. Intraocular pressure reduction in normal-tension glaucoma patients. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:1468–70. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31782-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, Johnson CA, Keltner JL, Miller JP, et al. For the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study Group. The ocular hypertension treatment study: A randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:701–13. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leske MC, Heijl A, Hyman L, Bengtsson B, Dong L, Yang Z EMGT Group. Predictors of long-term progression in the early manifest glaucoma trial. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1965–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowman R, Kirupananthan S. How to manage a patient with glaucoma in Africa. Community Eye Health J. 2006;19:38–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thommy CP, Bhar I. Trabeculectomy in Nigerian patients with open-angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1979;63:636–42. doi: 10.1136/bjo.63.9.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwab L, Steinkuller PG. Surgical treatment of open angle glaucoma is preferable to medical management in Africa. Soc Sci Med. 1983;17:1723–7. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90383-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adegbehingbe B, Majemgbasan T. A review of trabeculectomies at a Nigerian Teaching Hospital. Ghana Med J. 2007;41:176–80. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v41i4.55287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quigley HA, Buhrmann RR, West SK, Isseme I, Scudder M, Oliva MS. Long term results of glaucoma surgery among participants in an east African population survey. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:860–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.8.860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Omoti AE, Edema OT, Waziri-Erameh MJ. Acceptability of surgery as initial treatment for primary open angle glaucoma. J Medicine Biomedical Res. 2002;1:68–74. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sociodemographic overview. Lagos State, Nigeria: Family Health International; 2001. Feb, [Last accessed on January 31, 2011]. FHI. Report of the in-depth assessment of the HIV/AIDS situation; p. 8. Available from: http://www.fhi.org/NR/rdonlyres/er7qqkw6t3ctct6t35bfehfbsxbqpijzb 777lyknjrsfbaq5djdxokbjxkjj44hk7is5gw3loqnmcb/LagosInDepthAssessmNigeriaenhv.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 12.LASG. Lagos State Ministry of Health webpage. [Last accessed on August 5, 2010]. Available from: http://www.lsmoh.com/secondary.php .

- 13.Ogunbekun I, Ogunbekun A, Orobaton N. Private health care in Nigeria: Walking the Tightrope. Health Policy Plan. 1999;14:174–81. doi: 10.1093/heapol/14.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LASG. Lagos State Government. The Offiial website of Lagos State. [Last accessed on August 17, 2010]. Available from: http://www.lagosstate.gov.ng/index.php?page=subpage&spid=9&mnu=null .

- 15.Onyekwe LO, Okosa MC, Apakarna AI. Knowledge and attitude of eye hospital patients towards chronic open angle glaucoma in Onitsha. Niger Med J. 2009;50:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mafwiri M, Bowman R, Wood M. Primary open angle glaucoma presentation at a tertiary unit in Africa—intraocular pressure levels and visual status. Ophthal Epidemiol. 2005;12:299–302. doi: 10.1080/09286580500180572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabiu M. Cataract blindness and barriers to uptake of cataract surgery in a rural community of northern Nigeria. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:776–80. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.7.776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eze B, Chuka-Okosa C, Uche J. Traditional eye medicine use by newly presenting ophthalmic patients to a teaching hospital in south-eastern Nigeria: Socio-demographic and clinical correlates. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2009;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mutombo T. Assessing the use of TEM in Bukavu ophthalmic district, DRC. J Com Eye Health. 2008;21:66. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster A, Johnson G. Traditional eye medicine: Good or bad news? Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78:807. doi: 10.1136/bjo.78.11.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lunnela J, Kääriäinen M, Kyngäs H. The views of compliant glaucoma patients on counselling and social support. Scand J Caring Sci. 2010;24:490–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogun State health care financing study. 1–3. Lagos: Federal Ministry of Health; 1987. African Health Consultancy Services. [Google Scholar]