Abstract

To report a case of bilateral acute angle closure glaucoma (AACG) that occurred after cervical spine surgery with the use of glycopyrolate. A 59-year-old male who presented with severe bilateral bifrontal headache and eye pain that started 12 h postextubation from a cervical spine surgery. Neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg (4.5 mg) and glycopyrrolate 0.01 mg/kg (0.9 mg) were used as muscle relaxant reversals at the end of the surgery. Ophthalmic examination revealed he had bilateral AACG with plateau iris syndrome that was treated medically along with laser iridotomies. Thorough examination of anterior chamber should be performed preoperatively on all patients undergoing surgeries in the prone position and receiving mydriatic agents under general anesthesia.

Keywords: Acute Angle Closure Glaucoma, Cervical Spine Surgery, Glycopyrrolate

INTRODUCTION

Bilateral acute angle closure glaucoma (AACG) after general anesthesia with the administration of either antimuscurinic (scopolamine and atropine) or sympathomimetic (ephedrine) agents is a rarely reported event in the literature.1–4 Other precipitating factors include AIDS, herpes zoster, myelodisplastic syndrome, congenital anomalies, belpharoplasty, emotional stress, and drug sensitivity reactions.5–9 Bilateral AACG after cervical spine surgery under general anesthesia in a hypermetropic patient has been reported secondary to ephedrine administration.1 We report a case of bilateral AACG with a plateau iris syndrome after the use of glycopyrrolate during general anesthesia for cervical spine surgery.

CASE REPORT

We present a case of a 59-year-old male with hepatitis B, hypertension, and benign prostatic hypertrophy treated by 5α-reductase inhibitor. The patient was admitted to the hospital for cervical spine laminectomy. He was diagnosed with cervical disc disease involving C4-C5, C5-C6, and C6-C7 causing severe neck pain and paresthesia radiating to both upper and lower limbs. His past surgical history included surgical excision of multiple lipomas under general anesthesia with no reported complications. Ophthalmic history was significant for mild bilateral hyperopia (+1.50D).

On the day of surgery the patient was not premedicated. The vital signs upon induction were as follows: blood pressure 110/70 mmHg; heart rate 80 beats/min; O2 saturation 97% on room air. Two intravenous lines and a radial arterial line were inserted prior to induction. Intravenous midazolam (Dormicom; Hameln Pharmaceutical, Germany) 2 mg IV and (Fentanyl; Hameln Pharmaceutical, Germany) intravenous fentanyl 50 mcg were administered. While awake, nasal intubation was performed after bilateral superior laryngeal nerve block, transtracheal block, and topical anesthesia. After preoxygenation, intravenous induction was administered with Propofol (Diprivan; Frenius Kabi, Germany) 200 mg, Rocuronium (Esmeron; Organo, Netherland) 50 mg, Fentanyl 250 μg, Midazolam 1 mg, and Xylocaine (Lidocaine Hydrochloride; Hameln Pharmaceutical, Germany) 100 mg. Dexamethasone (Dexamed; Medochemie LTS, Cyprus) 16 mg was given intravenously after induction. Both eyes were covered with eye pads and taped. The patient was moved intoa prone position. The head was stabilized with a horseshoe head rest and the anesthesiologist made sure that no pressure was applied on the eyes or forehead. Remifentanil (Ultiva; GSK, Italy) and cisatracurium (Nimbex; GSK, Italy) intravenous infusions were started.

Throughout the procedure, vital signs were maintained within the following limits: Systolic blood pressure 100–130 mmHg; diastolic blood pressure 50–80 mmHg; heart rate 50–70 beats/ min; O2 saturation 99–100%; temperature 35.7–36.7°C. Four liters of lactated Ringers were infused intraoperatively that lasted 5 h and 30 min. After the laminectomy was performed, the patient was reversed back to the supine position. Muscle relaxants were reversed with neostigmine (Prostigmine; Valeant, Switzerland) 0.05 mg/kg (4.5 mg) and glycopyrrolate (Robinul; American Regent Inc, USA) 0.01 mg/kg (0.9 mg). The patient was extubated fully awake and cooperative and was transferred to the recovery room in stable condition.

In the early postoperative period, the patient had no ocular complaints. Approximately 12 h following recovery from general anesthesia he developed progressive bilateral frontal headache associated with nausea that persisted despite analgesics. CT scan of the brain ordered by the orthopedics service was normal. Twenty-four hours postoperatively, he started complaining of bilateral blurring of vision along with headache at which time the ophthalmology service was consulted.

Ophthalmic examination indicated Snellen visual acuity of 20/100 in both eyes. There was corneal edema bilaterally with an intraocular pressure of 65 mmHg in each eye. Reaction to light was sluggish in both pupils. The anterior chambers were shallow and gonioscopy revealed bilateral plateau iris occluding the trabecular meshwork 360°. Both irises were pigmented dark-brown. No lens thickening was observed bilaterally. The patient was diagnosed with bilateral AACG with plateau iris syndrome. Acetazolamide (Diamox; Sigma Pharmaceuticals Ltd, New Zealand) 500 mg PO and intravenous Mannitol (500 cc over 40 min) were administered and the patient was instructed to instill topical antiglaucoma drops including dorzolamide hydrochloride–timolol maleate (Cosopt; Merck, USA) and bimatoprost (Lumigan; Allergan, USA) ophthalmic solution. On follow up over the next 12 h, visual acuity improved to 20/35 bilaterally with significant decrease in corneal edema. The intraocular pressure decreased to 21 mmHg in the right eye and 14 mmHg in the left eye, respectively. The anterior chambers remained shallow, hence peripheral iridotomies at 10 and 12 o’clock were performed on both eyes. The patient was returned for 1 month follow-up and his vision was 20/20 in both eyes with an IOP of 13 mmHg and 15 mmHg in the right and left eyes, respectively. Peripheral iridotomies were patent bilaterally.

DISCUSSION

AACG occurs in females four times greater than in males due to the anatomically more compact anterior chamber.10 Other risk factors include genetic predisposition, shallow anterior chamber depth, high hypermetropia, increased lens thickness, small corneal diameter, and increased age.11,12 AACG a rare postoperative complication of (nonophthalmic) surgeries performed under general anesthesia. Large doses of antimuscarinic agents are often administered intravenously during general anesthesia to prevent the side effects of neostigmine methylsulfate, which is used to reverse the effect of nondepolarizing muscle relaxants. This causes mydriasis that can predispose patients with shallow anterior chambers to progress to AACG especially in lightly pigmented irides.4,13

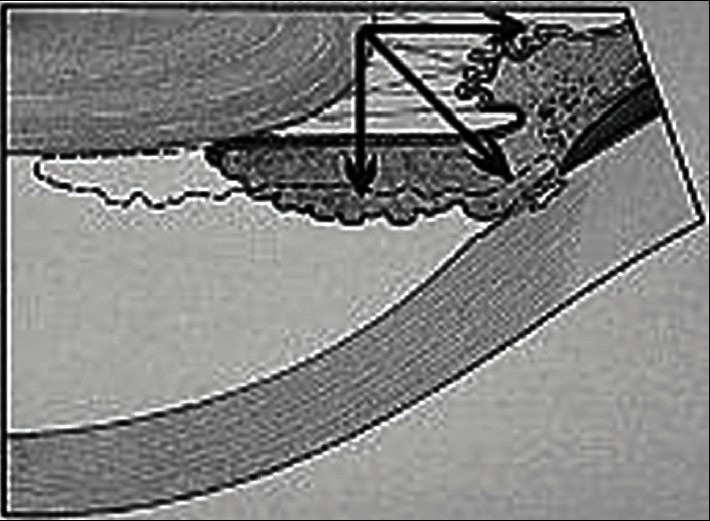

We postulate that two factors contributed to the formation of plateau iris-like acute angle closure and obliteration of the trabecular meshwork in our patient. First the gravitational effect, induced by the prone position during surgery is a well documented cause of increased intraocular pressure.14,15 This promoted the forward shift of the lens/iris apparatus. Second the tangential effect, created by the movement of the iris dilator muscles due to the mydriatic effect of glycopyrrolate toward the angle enhancing iris apposition against the irido-corneal angle [Figure 1]. Although neostigmine has a miotic effect and could have aborted the attack, its duration of action is significantly shorter than the anticholinergic effect of glycopyrrolate.16,17 Glycopyrrolate is a synthetic anticholinergic muscarinic competitive antagonist with a quaternary ammonium structure of the phenyacetate drug class. Glycopyrrolate is used as an adjunct to acetylcholine esterase inhibitors to antagonize their cholinergic effects. The anticholinergic effect of glycopyrrolate lasts for 8–12 h. In our case, the patient experienced ocular pain approximately 24 h postoperatively. This was likely due to the masking effect of the analgesics and sedatives that the patient received during the early postoperative period.

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of the summation of vector forces that lead to angle closure during mydriasis and the prone position

In conclusion, this is the first case of bilateral AACG induced by glycopyrrolate (PUBMED search: bilateral angle closure glaucoma, glycopyrrolate). We recommend that an assessment of the anterior chamber depth should be included in the preoperative checklist of every patient undergoing surgeries in the prone position under general anesthesia. This can be easily done using a penlight illumination test for anterior chamber depth by the anesthesiologist. Also, the use of topical pilocarpine administered at the end of the surgery should be considered for patients at risk in order to prevent an AACG attack.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gayat E, Gabison E, Devys JM. Case report: Bilateral angle closure glaucoma after general anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:126–8. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182009ad6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fazio DT, Bateman JB, Christensen RE. Acute angle-closure glaucoma associated with surgical anesthesia. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103:360–2. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1985.01050030056021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ates H, Kayikçioğlu O, Andaç K. Bilateral angle closure glaucoma following general anesthesia. Int Ophthalmol. 1999;23:129–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1010667502014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz H, Apt L. Mydriatic effect of anticholinergic drugs used during reversal of nondepolarizing muscle relaxants. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;88:609–12. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(79)90523-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al Halel A, Hirsh A, Melamed S, Blumental M. Bilateral simultaneous spontaneous angle closure in a Herpes zoster patient (letter) Br J Ophthalmol. 1991;75:510. doi: 10.1136/bjo.75.8.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meige P, Cohen H, Morin B, Athlani A. Acute bilateral glau- coma in an LAV-positive subject. Bull Soc Ophthalmol Fr. 1989;89:449–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UlIman S, Wilson RP, Schwartz L. Bilateral angle closure glaucoma in association with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;101:419–24. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(86)90639-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright KW, Chrousos GA. Weil-Marchesani syndrome with bilateral angle closure glaucoma. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1985;22:129–32. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19850701-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith DL, Skuta GL, Trobe JD, Weinberg AB. Angle closure glaucoma as initial presentation of myelodysplastic syndrome. Can J Ophthalmol. 1990;25:306–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritch R, Lowe RF. Angle closure glaucoma: Mechanisms and epidemiology. In: Ritch R, Shields MB, Krupin T, editors. The glaucomas. 2nd ed. St Louis: CV Mosby Year Book Inc; 1996. pp. 801–19. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowe RF. Aetiology of the anatomical basis for primary angle-closure glaucoma: Biometrical comparisons between normal eyes and eyes with primary angle-closure glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1970;54:161–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.54.3.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lotery AJ, Frazer DG. Iatrogenic acute angle closure glaucoma masked by general anaesthesia and intensive care. Ulster Med J. 1995;64:178–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gayer S. Prone to blindness: Answers to postoperative visual loss. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:11–2. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181fe772d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng MA, Todorov A, Tempelhoff R, McHugh T, Crowder CM, Lauryssen C. The effect of prone positioning on intraocular pressure in anesthetized patients. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:1351–5. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200112000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyams SW, Friedman Z, Neumann E. Elevated intraocular pressure in the prone position: A new provocative test for angle-closure glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1968;66:661–72. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(68)91287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blitt CD, Moon BJ, Kartchner CD. Duration of action of neostigmine in man. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1976;23:80–4. doi: 10.1007/BF03004997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haddad EB, Patel H, Keeling JE, Yacoub MH, Barnes PJ, Belvisi MG. Pharmacological characterization of the muscarinic receptor antagonist, glycopyrrolate, in human and guinea-pig airways. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:413–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]