Abstract

Purpose

To present the case of a premature infant who displayed immature feeding progression due to nasal occlusion.

Subjects

Two male preterm infants 33 weeks gestational age at birth from a larger randomized trial.

Design

Comparative case study.

Methods

Using a prospective design, feeding assessments were conducted weekly from initiation of oral feeding until hospital discharge. Sucking organization was measured using the Medoff-Cooper Nutritive Sucking Apparatus (M-CNSA) which measured negative sucking pressure generated during oral feedings. Oral and nasogastric (NG) intake and vital signs were recorded.

Results

At 35 weeks, Infant A demonstrated an immature feeding pattern with NG feedings prevailing over oral feedings. When attempting to feed orally, Infant A exhibited labored breathing and an erratic sucking pattern. During the third weekly feeding evaluation, nasal occlusion was discovered, the NG tube was discontinued, and neosynephrene and humidified air were administered. Following treatment, Infant A’s sucking pattern normalized and the infant maintained complete oral feeding. Infant B demonstrated normal feeding progression.

Conclusion

Nasal occlusion prevented Infant A from achieving successful oral feeding. The M-CNSA has the ability to help clinicians detect inconsistencies in the breath-suck-swallow feeding patterns of infants and objectively measures patterns of nutritive sucking. The M-CNSA has the potential to influence clinical decision making and identify the need for intervention.

Keywords: Premature Infant, Nasal Obstruction, Bottle Feeding, Sucking Behavior, Nutritive Sucking Patterns, Nasogastric Tube, and Feeding Progression

Introduction

Oral feeding is a complex task involving the integration, maturation, and coordination of multiple systems within the body1, 2. Due to their neurologic immaturity and difficulty in regulating autonomic functions, preterm infants often experience difficulty feeding by mouth3, 4. Nevertheless, successful oral feeding must be achieved before a preterm infant can transition from the hospital to home5. Supporting the development of oral feeding skills is an important area of clinical practice. Much research has been conducted to develop an understanding of preterm infant feeding behaviors and to determine and improve strategies to support the preterm infant’s feeding progression following birth6.

Coordination of sucking, swallowing, and breathing is the most highly organized behavior required of a preterm infant7, 8. Sucking and swallowing are ororhythmic motor behaviors that require coordination of the mouth, palate, pharynx, larynx, and esophagus9. This coordination occurs around 32 to 34 weeks gestational age1, 4, 7, 10. During pharyngeal swallowing, respiration is inhibited centrally11. The infant may make an effort to breathe, but breathing may remain obstructed for several seconds after swallowing has occurred12. The coordination of swallowing and breathing matures more slowly and occurs around 37 weeks gestational age2, 13–15. A healthy preterm infant should achieve synchronized coordination of sucking, swallowing and breathing on a 1:1:1 or 2:2:1 ratio by 36 to 37 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA) with most premature infants attaining maximal oral feedings by 35 to 37 weeks PMA 16–19. In clinical practice, however, many preterm infants are able to initiate oral feeding as early as 28 to 32 weeks PMA20, 21. Recent research supports the use of individualized assessments and infant feeding cues to determine initiation of oral feedings4, 20.

When a preterm infant feeds from a bottle, continuous sucking is common at the onset of feeding which is followed by intermittent sucking22. Continuous sucking involves no interruptions for breathing and is representative of a single, long sucking burst23. This sucking pattern results in rapid milk flow and greater milk consumption24–26 but can lead to hypoxemia due to inhibited respiration23, 27–31. An intermittent phase immediately follows continuous sucking, during which the sucking bursts begin to shorten and the intervals between sucking bursts lengthen allowing respiration to take place23. If the breath-suck-swallow mechanisms are uncoordinated or immature, the infant may experience respiratory compromise evidenced by bradycardia, tachypnea between sucking bursts, apnea, nasal flaring, or hypoxemia3, 32. A preterm infant’s ability to recover from an oxygen desaturation episode during feeding is dependent on the duration of the breathing period and the ability of the infant to increase ventilation during sucking pauses18.

Enteral feeding is commonly used to provide premature infants with necessary calories and nutrients when oral feeding is not possible due to neuromuscular immaturity10, 33. Nasogastric (NG) or orogastric tube feedings are typically used before and during the transition from tube feedings to oral feedings10. The feeding tubes are usually left in place to decrease the need for invasive procedures and to allow for clustered care. Infants are obligate nose breathers so any obstruction to the nares can have significant respiratory implications34. The presence of indwelling NG tubes has been associated with increased nasal resistance and nasal airway resistance35 as well as shortened sucking bursts and lengthened oxygen desaturation events during feeding29, 35. Overtime, the presence of feeding tubes can also impede the development of breath-suck-swallow coordination and may lead to oral sensitivity18, 21, 36.

The purpose of this paper is to present the case of a premature infant who displayed an immature feeding progression due to nasal occlusion from an NG tube. The feeding progression of another male infant born at the same gestational age who did not receive enteral feedings is presented as a comparison. Sucking parameters for both infants are examined.

Case Report

This comparative case study follows the course of two infants who were enrolled in a larger randomized clinical trial testing a multisensory developmental and participatory guidance intervention for mothers of healthy premature infants born between 29 and 34 weeks gestational age. The two infants in this case study were admitted to a level III neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) at a community-based hospital in a large Midwestern city. Exclusion criteria for the larger study included infants who had congenital anomalies, necrotizing enterocolitis, brain injury, chronic lung disease, prenatal drug exposure or who were HIV positive. Mothers who were identified as illicit drug users and mothers who were not the legal guardian of their infants were also excluded. This study was granted institutional review board approval by the university and the clinical site. Written and informed consent was obtained from the mothers of the two infants presented in this case study.

Infant A was a 1950 gram male, born via cesarean section at 33 weeks gestational age to 30-year-old gravida 3, para 2 mother. Two doses of dexamethasone were administered to the mother prior to delivery. Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes were 9 and 9. Umbilical cultures yielded growth of staphylococcus and gram negative rods which was treated with mupirocin ointment. Infant A received supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula for less than 24 hours after birth and was then placed on room air. An NG tube was inserted to facilitate feedings. Alternate NG and PO feedings were initiated on the third day of life.

Infant B was purposefully selected from the larger study sample to compare to Infant A due to similar infant characteristics. Infant B was a 1895 gram male, born via vacuum assisted vaginal delivery at 33 weeks gestational age to a 20-year-old primiparous mother. Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes were 7 and 8. Infant B did not receive oxygen therapy and did not receive NG feedings.

Data Collection Procedures

According to the protocol for the larger randomized clinical trial, weekly oral feeding assessments were conducted on both infants from initiation of oral feeding through hospital discharge by a registered nurse. Intake volume (PO and NG) and sucking patterns were recorded during each assessment. Vital signs were monitored throughout the entire feeding period and recorded in addition to notes about the feedings. Sucking patterns were measured over a five-minute period using the Medoff-Cooper Nurtive Sucking Apparatus (M-CNSA) and associated software37. At the end of the five minute feeding assessment, the remainder of the prescribed volume of formula or breast milk was delivered to the infant orally using a regular nipple or via NG tube. The total volume consumed at each feeding and the route of ingestion was recorded.

The M-CNSA provides a continuous record of the negative intraoral pressure generated by the infant throughout the five minute oral feeding assessment. The M-CNSA is comprised of an ordinary silicone nipple containing an embedded capillary calibrated for metered flow of fluid and a pressure transducer embedded in a second tube. The minimum pressure used to detect a nutritive suck was set at 7 mmHg. The M-CNSA is a quantitative instrument that objectively measures nutritive sucking parameters in both preterm and full term infants and has been used to predict developmental outcomes37–42. Sucking patterns were analyzed based on several parameters measured by the M-CNSA: total number of sucks during the five minute assessment, mean adjusted maximum sucking pressure, mean number of sucks per sucking burst, and the mean intersuck interval. An increase in number of sucks, mean adjusted maximum pressure, and number of sucks per burst and a decrease in the mean intersuck interval indicates a more mature sucking pattern.

Results

Infant A was hospitalized for 25 days and completed four weekly oral feeding assessments. The initial feeding assessment was conducted at 3 days of life and Infant A was discharged to home one day after the fourth assessment. The nursing staff noted that Infant A was a poor feeder. Infant B was hospitalized for 11 days and completed two weekly oral feeding assessments. Infant B was four days old at the initial assessment and was discharged to home on the day of the second weekly feeding assessment.

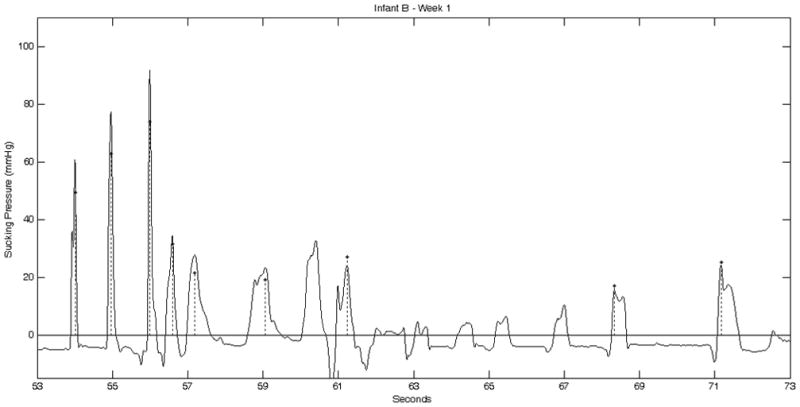

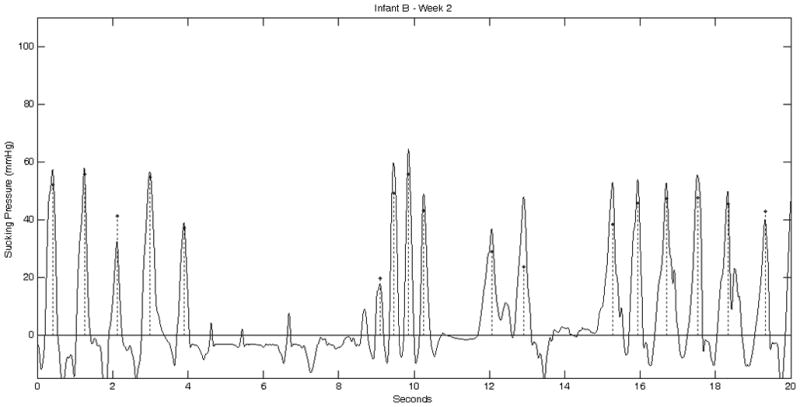

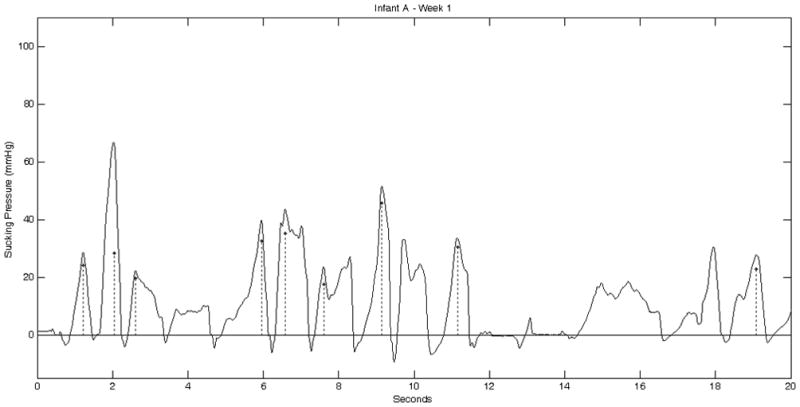

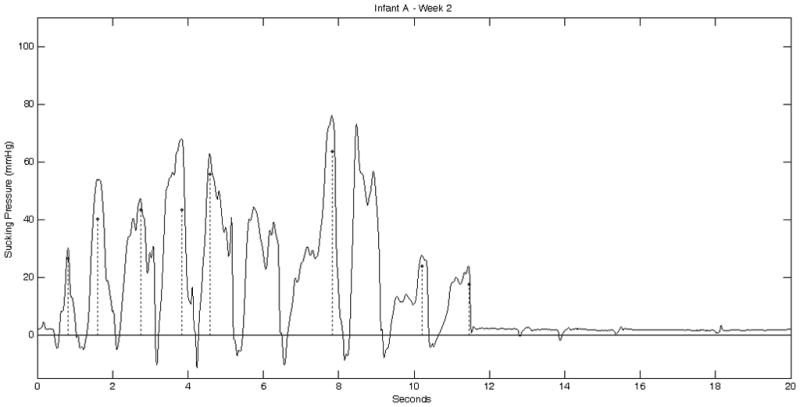

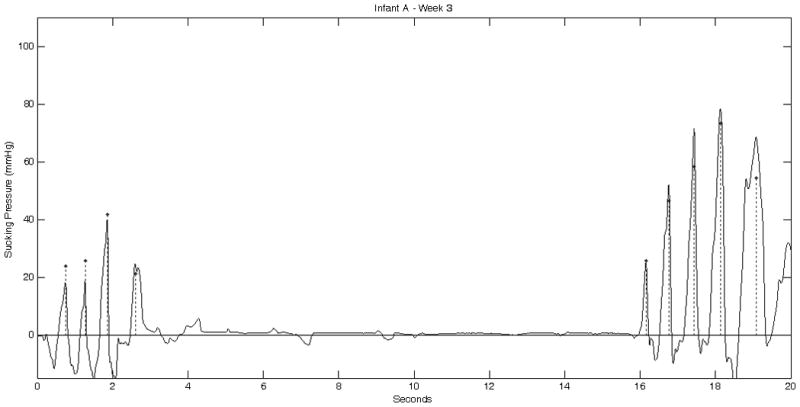

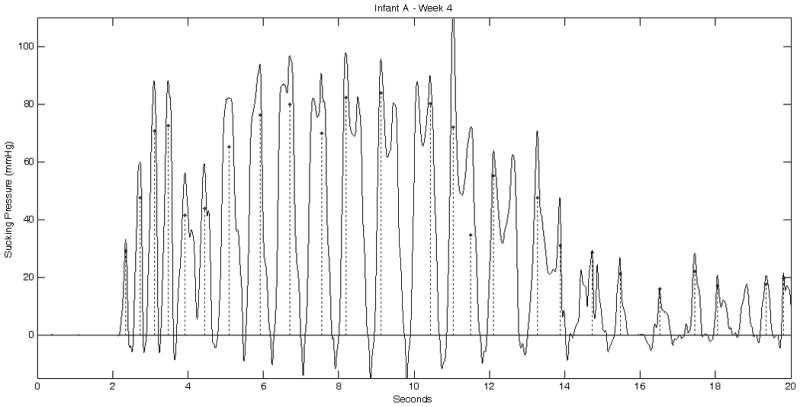

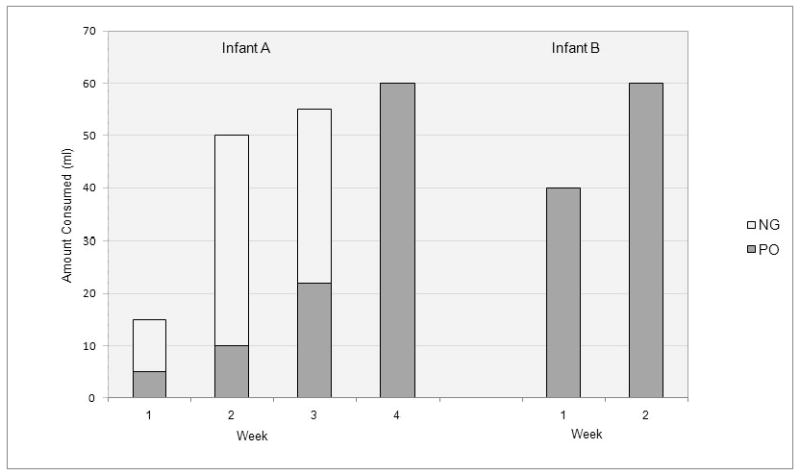

Sucking parameters measured by the M-CNSA were recorded and graphed over time to display sucking patterns. Because the entire five minute feeding assessment cannot be displayed here, a representative 20 second strip is presented for each weekly evaluation. Infant B’s sucking strips show an improved sucking pattern from weeks one to two with a greater number of sucks per sucking burst and a higher sucking pressure during week two compared to week one (figures 1–2). In comparison, Infant A’s sucking strips show an erratic sucking pattern and lack of a long continuous initial sucking burst in weeks one through three (figures 3, 4, and 5). During these first three feeding evaluations, Infant A was noted to be experiencing labored breathing. During week three, Infant A also displayed subcostal retractions. Oxygen saturation was maintained above 95%. During this feeding, it was determined that one nare was occluded due to nasal congestion and the other nare was also occluded due to the placement of the NG tube. The nasal congestion was treated with one dose of nasal Neo-Synephriene and the infant was placed on humidified air. The NG tube was removed and an oral gastric (OG) tube was then placed. The OG tube was removed prior to the fourth feeding assessment and Infant A continued to feed orally without OG supplementation until discharge. Infant A’s sucking strip for week four shows a longer, more organized sucking burst with a higher sucking pressure following the removal of the NG tube and treatment for nasal congestion (figure 6).

Figure 1.

Infant B Week 1 Sucking Strip

Figure 2.

Infant B Week 2 Sucking Strip

Figure 3.

Infant A Week 1 Sucking Strip

Figure 4.

Infant A Week 2 Sucking Strip

Figure 5.

Infant A Week 3 Sucking Strip

Figure 6.

Infant A Week 4 Sucking Strip

The total volume consumed and feeding route at each weekly feeding assessment is displayed in figure 7. Both infants increased their total intake over time. Infant A progressed from receiving the majority of his feedings via NG tube during weeks one through three to complete oral feeding on week four. Infant B received exclusive oral feedings during both weekly evaluations.

Figure 7.

Total Consumption for Infants A and B at each Weekly Feeding Evaluation

A summary of sucking parameters for each weekly feeding observation is presented in Table 1. Infant B demonstrated an expected pattern of sucking maturation with a vast increase in number of sucks, mean adjusted maximum pressure, and mean number of sucks per burst and a decrease in mean inter-suck interval between weeks one and two. In comparison, Infant A demonstrated very little change in number of sucks, mean adjusted maximum pressure, mean number of sucks per burst, or mean inter-suck interval between weeks one and three, but showed a dramatically improved sucking pattern during week four after the NG tube was removed and the infant was treated for nasal congestion.

Table 1.

Sucking Parameters for Weekly Feeding Observations during Initial Hospitalizations for Infant A and Infant B, During 5 Minute Feeding Evaluation Measured using the Medoff-Cooper Nutritive Sucking Apparatus

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant A | ||||

| Number of Sucks | 85 | 85 | 97 | 202 |

| Mean adjusted maximum pressure (mmHg) | 34.9 | 34.9 | 39.6 | 38.7 |

| Mean number of sucks per burst | 3.6 | 3.6 | 5.4 | 7.5 |

| Mean Inter-suck Interval (seconds) | 3.5 | 3.5 | 2.7 | 1.5 |

| Infant B* | ||||

| Number of Sucks | 84 | 154 | -- | -- |

| Mean adjusted maximum pressure (mmHg) | 26.4 | 52.8 | -- | -- |

| Mean number of sucks per burst | 3.4 | 5.6 | -- | -- |

| Mean Inter-suck Interval (seconds) | 3.6 | 2.0 | -- | -- |

Infant B was discharged to home feeding well on the same day of the observed feeding in Week 2, sucking parameters are not available for weeks 3 and 4

Discussion

Gestational age, PMA, birth weight, sex, and feeding experience have all been found to be significant predictors of feeding performance in premature infants6, 13, 14, 19, 42–44. Individual components of sucking organization including sucking pressure, number of sucking bursts, burst duration, and number of sucks per minute change significantly between day one and day two of life39 and with increased experience with oral feeding43. Therefore, it would be expected that both Infant A and Infant B would demonstrate similar feeding progressions as they were born at similar gestational ages, had similar birth weights, and had similar oral feeding experience.

Both infants displayed similar sucking parameters during the initial feeding assessment. Infant A showed very little maturation of sucking patterns between weeks one and three. In comparison, Infant B displayed vast maturation from week one to week two. Once the NG tube was removed during week three and the infant was treated for nasal congestion, Infant A displayed a more mature sucking pattern with an increase in number of sucks and mean number of sucks per burst and a significant decrease in mean inter-suck interval. Infant A’s mean adjusted maximum sucking pressure did not change significantly over time, but he displayed a decreased inter-suck interval once the nasal airway was unblocked. With the nasal airway occluded, Infant A was capable of generating the pressure needed to transfer milk but was unable to breathe. In this state, Infant A was forced to maintain a long inter-suck interval generating few sucks per burst which resulted in a low number of sucks over the course of the feeding assessment.

Infant A might have displayed a pattern of sucking progression similar to Infant B between weeks one to two had his nose not been occluded. This could have resulted in a decrease in the duration of the hospital stay by two weeks. A shortened hospital stay would have reduced hospital costs and preserved hospital resources45–47. An earlier discharge would have also decreased the financial and emotional costs to the family associated with having an infant in the NICU and would have facilitated earlier family bonding48, 49.

Implications for Practice

This case study demonstrates the value of the M-CNSA in assisting clinicians to accurately identify problems in sucking parameters and lack of feeding progression in preterm infants. Sucking parameters including number of sucks per feeding, mean adjusted maximum pressure, mean number of sucks per burst, and mean inter-suck interval can be measured by the M-CNSA. Detailed information about infant sucking patterns provided by the M-CNSA allows researchers and practitioners to measure infant sucking progression and maturation over time.

The use of the M-CNSA provided an objective assessment of sucking progression and was very useful in identifying this infant’s clinical problem and need for intervention. Review of the sucking strip confirmed the nursing staff’s clinical assessment of poor feeding progression. The objective data provided by the M-CNSA demonstrated that Infant A was not displaying the expected level of sucking maturation based on his PCA and level of experience. The assessment of sucking strips is not currently the standard for clinical practice but has the potential to enhance clinical decision-making. This may result in decreased length of hospital stay, cost savings, and improved family experience.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Nursing Research (1 R01 HD050738-01A2), and the Harris Foundation. We also wish to acknowledge the infants and mothers who participated in this research.

References

- 1.Delaney AL, Arvedson JC. Development of swallowing and feeding: Prenatal through first year of life. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2008;14(2):105–117. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lau C, Smith EO, Schanler RJ. Coordination of suck-swallow and swallow respiration in preterm infants. Acta Paediatrica. 2003;92(6):721–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barlow SM. Oral and respiratory control for preterm feeding. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;17(3):179–186. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e32832b36fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones LR. Oral feeding readiness in the neonatal intensive care unit. Neonatal Netw. 2012;31(3):148–155. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.31.3.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Hospital discharge of the high-risk neonate. Pediatrics. 2008;122(5):1119–1126. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howe TH, Sheu CF, Hinojosa J, Lin J, Holzman IR. Multiple factors related to bottle-feeding performance in preterm infants. Nursing Research. 2007;56(5):307–311. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000289498.99542.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bu’Lock F, Woolridge MW, Baum JD. Development of co-ordination of sucking, swallowing and breathing: Ultrasound study of term and preterm infants. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1990;32(8):669–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1990.tb08427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medoff-Cooper B, Verklan T, Carlson S. The development of sucking patterns and physiologic correlates in very-low-birth-weight infants. Nurs Res. 1993;42(2):100–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau C, Schanler RJ. Oral motor function in the neonate. Clinics in Perinatology. 1996;23(2):161–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groh-Wargo S, Sapsford A. Enteral nutrition support of the preterm infant in the neonatal intensive care unit. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 2009;24(3):363–376. doi: 10.1177/0884533609335310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doty RW, Bosma JF. An electromyographic analysis of reflex deglutition. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1956;19(1):44–60. doi: 10.1152/jn.1956.19.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koenig JS, Davies AM, Thach BT. Coordination of breathing, sucking, and swallowing during bottle feedings in human infants. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1990;69(5):1623–1629. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.5.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amaizu N, Shulman RJ, Schanler RJ, Lau C. Maturation of oral feeding skills in preterm infants. Acta Paediatrica. 2008;97(1):61–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cunha M, Barreiros J, Goncalves I, Figueiredo H. Nutritive sucking pattern–from very low birth weight preterm to term newborn. Early Human Development. 2009;85(2):125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathew OP. Respiratory control during nipple feeding in preterm infants. Pediatric Pulmonology. 1988;5(4):220–224. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950050408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paludetto R, Robertson SS, Martin RJ. Interaction between nonnutritive sucking and respiration in preterm infants. Biology of the Neonate. 1986;49(4):198–203. doi: 10.1159/000242531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolff PH. The serial organization of sucking in the young infant. Pediatrics. 1968;42(6):943–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathew OP. Breathing patterns of preterm infants during bottle feeding: Role of milk flow. Journal of Pediatrics. 1991;119(6):960–965. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jadcherla SR, Wang M, Vijayapal AS, Leuthner SR. Impact of prematurity and co-morbidities on feeding milestones in neonates: A retrospective study. J Perinatol. 2010;30(3):201–208. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirk AT, Alder SC, King JD. Cue-based oral feeding clinical pathway results in earlier attainment of full oral feeding in premature infants. J Perinatol. 2007;27(9):572–578. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeMauro SB, Patel PR, Medoff-Cooper B, Posencheg M, Abbasi S. Postdischarge feeding patterns in early- and late-preterm infants. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2011;50(10):957–962. doi: 10.1177/0009922811409028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill AS, Kurkowski TB, Garcia J. Oral support measures used in feeding the preterm infant. Nursing Research. 2000;49(1):2–10. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiao SY. Comparison of continuous versus intermittent sucking in very-low-birth-weight infants. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1997;26(3):313–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1997.tb02147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rocha NM, Martinez FE, Jorge SM. Cup or bottle for preterm infants: Effects on oxygen saturation, weight gain, and breastfeeding. Journal of Human Lactation. 2002;18(2):132–138. doi: 10.1177/089033440201800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Case-Smith J, Cooper P, Scala V. Feeding efficiency of premature neonates. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1989;43(4):245–250. doi: 10.5014/ajot.43.4.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill AS. Preliminary findings: A maximum oral feeding time for premature infants, the relationship to physiological indicators. Matern Child Nurs J. 1992;20(2):81–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shivpuri CR, Martin RJ, Carlo WA, Fanaroff AA. Decreased ventilation in preterm infants during oral feeding. J Pediatr. 1983;103(2):285–289. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(83)80368-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathew OP, Clark ML, Pronske ML, Luna-Solarzano HG, Peterson MD. Breathing pattern and ventilation during oral feeding in term newborn infants. J Pediatr. 1985;106(5):810–813. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(85)80363-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiao SY, Brooker J, DiFiore T. Desaturation events during oral feedings with and without a nasogastric tube in very low birth weight infants. Heart Lung. 1996;25(3):236–245. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(96)80034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen CH, Wang TM, Chang HM, Chi CS. The effect of breast- and bottle-feeding on oxygen saturation and body temperature in preterm infants. Journal of Human Lactation. 2000;16(1):21–27. doi: 10.1177/089033440001600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thoyre SM, Carlson JR. Preterm infants’ behavioural indicators of oxygen decline during bottle feeding. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003;43(6):631–641. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02762.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poets CF, Langner MU, Bohnhorst B. Effects of bottle feeding and two different methods of gavage feeding on oxygenation and breathing patterns in preterm infants. Acta Paediatrica. 1997;86(4):419–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb09034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Premji SS, Chessell L. Continuous nasogastric milk feeding versus intermittent bolus milk feeding for premature infants less than 1500 grams. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011;(11):CD001819. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001819.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kopelman AE. Airway obstruction in two extremely low birthweight infants treated with oxygen cannulas. J Perinatol. 2003;23(2):164–165. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stocks J. Effect of nasogastric tubes on nasal resistance during infancy. Arch Dis Child. 1980;55(1):17–21. doi: 10.1136/adc.55.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shiao SY, Youngblut JM, Anderson GC, DiFiore JM, Martin RJ. Nasogastric tube placement: Effects on breathing and sucking in very-low-birth-weight infants. Nurs Res. 1995;44(2):82–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Medoff-Cooper B, Shults J, Kaplan J. Sucking behavior of preterm neonates as a predictor of developmental outcomes. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30(1):16–22. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318196b0a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Medoff-Cooper B, Bilker W, Kaplan JM. Suckling behavior as a function of gestational age: A cross-sectional study. Infant Behavior and Development. 2001;24(1):83–94. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Medoff-Cooper B, Bilker W, Kaplan JM. Sucking patterns and behavioral state in 1- and 2-day-old full-term infants. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2010;39(5):519–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01173.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Medoff-Cooper B, McGrath JM, Bilker W. Nutritive sucking and neurobehavioral development in preterm infants from 34 weeks PCA to term. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2000;25(2):64–70. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200003000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Medoff-Cooper B, Weininger S, Zukowsky K. Neonatal sucking as a clinical assessment tool: Preliminary findings. Nursing Research. 1989;38(3):162–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wrotniak BH, Stettler N, Medoff-Cooper B. The relationship between birth weight and feeding maturation in preterm infants. Acta Paediatrica. 2009;98(2):286–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.01111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pickler RH, Best A, Crosson D. The effect of feeding experience on clinical outcomes in preterm infants. J Perinatol. 2009;29(2):124–129. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White-Traut RC, Berbaum ML, Lessen B, McFarlin B, Cardenas L. Feeding readiness in preterm infants: The relationship between preterm behavioral state and feeding readiness behaviors and efficiency during transition from gavage to oral feeding. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2005;30(1):52–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gilbert WM, Nesbitt TS, Danielsen B. The cost of prematurity: Quantification by gestational age and birth weight. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(3):488–492. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00617-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kirkby S, Greenspan JS, Kornhauser M, Schneiderman R. Clinical outcomes and cost of the moderately preterm infant. Adv Neonatal Care. 2007;7(2):80–87. doi: 10.1097/01.anc.0000267913.58726.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Russell RB, Green NS, Steiner CA, et al. Cost of hospitalization for preterm and low birth weight infants in the United States. Pediatrics. 2007;120(1):e1–e9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Altman M, Vanpee M, Bendito A, Norman M. Shorter hospital stay for moderately preterm infants. Acta Paediatrica. 2006;95(10):1228–1233. doi: 10.1080/08035250600589058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Argus BM, Dawson JA, Wong C, Morley CJ, Davis PG. Financial costs for parents with a baby in a neonatal nursery. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2009;45(9):514–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2009.01551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]