Sir,

Although modern medicine has changed for better dispensing managements, the evidence still continues to mount that adverse drug reactions to medicine related to dispensing practices. The risk associated with dispensing of drugs is one of the major problems in achieving drug safety.[1] Several studies showed that medication errors in prescription, dispensing and delivery had increased the harmful potentials of drugs in hospitals.[2–5] An appropriate dispensing system is an important ally for prevention or reduction of medication errors. Considering all we decided to investigate dispensing errors in health facilities using patient care indicators validated by World Health Organization.[1] A cross sectional survey was planned to assess primary care facilities: Teaching hospital (TH), General hospital (GH) and District hospital (DH) and the hospital in Galle.

Our study was a prospective, comparative cross sectional survey carried out for six months at TH, GH and DH. All patients attending the morning clinics in outpatient Departments were included in our study. Ethical clearance was granted by the ethics and review committee of the institution.

Totally 422 encounters were observed by the trained medical students and medical officers. The patients visited the OPD from 9.00 to 11.00 AM were selected and prescription observations questionnaire. Following measuring tools were used to assess the degree of patient care and dispensing errors. Dispensing time (DT), percentage of drugs actually dispensed (PDAD), number of drugs adequately labeled (NDAL), number of drugs dispensed (NDD), were calculated. DT was measured using the total time that dispenser spent with patients in the total process of labeling and dispensing. Average calculation of the dispensing time was done by dividing the total time all dispensed encounters by the number of dispensed. PDAD is the measurement of drug availability in a health facility. It means the degree to which health facilities are able to provide the drugs which were prescribed. NDAL was one of the other measuring tools to assess degree of patient care delivered by the pharmacist. It is also important to improve the treatment efficacy of a patient. Labeling is a method of delivery of drug message and can prevent drug induced toxicities or reactions. It was the number of drug packages containing correct drug information in each prescription.

NDD is the number of drugs dispensed in prescriptions. Descriptive statistics for different groups was worked out and correlation coefficient was calculated to determine the correlation between different parameters. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Microcal origin 4.1 and Microsoft Excel whenever applicable.

We found that DT and NDD were positively correlated (r = +0.53, P < 0.001) in mean values of all health sectors. All correlations between DT and NDD were similar in different type of health care facility in our study (r = +0.48, P < 0.0001), DH (r = 0.68, P=<0.0001) and GH (r = 0.67, P = <0.0001). In addition to that, the relationship between the DT and the NDAL in all three hospital, dispensing time was not affected by the degree of adequate drug labeling in DH and GH but significantly related in TH.

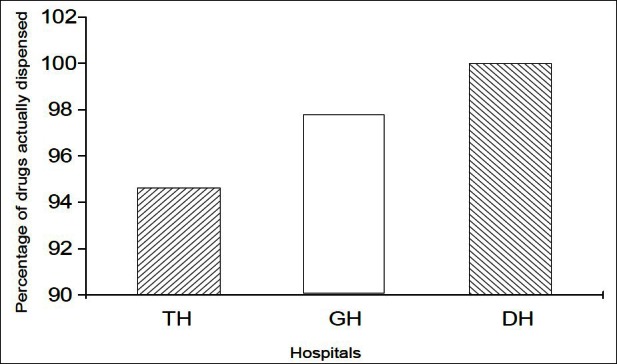

Percentages of drugs dispensed (PDAD) was 94.64 in TH, 79 in GH and 100 in DH. According to the recommendation by WHO ideal PDAD should be 100% in a standard hospital with good patient care rank. It was remarkable to report that PDAD was low in tertiary care hospitals and 100% in DH where only the basic facilities are available [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The percentage of drugs dispensed at different hospitals. PDAD = 94.64 in TH, 97.79 in GH and 100 in DH.

We found that average dispensing time (ADT) is short in all hospitals hence dispensers spent only short time in our government hospitals when compared with WHO recommendation values (3 min).[1] Short ADT is one of the many known factors to cause high risk of dispensing errors. We understood that very short ADT could be related to the peculiar pharmacist practice for the absence of explanation in dosage regimen, precautions and clinically important side effect of the given drugs. According to our results, we found high DT was related to the number of drugs in all three hospitals. Regarding the labeling process, DT was not related to the drug labeling in none of the hospitals. This is one of the evidence to say that dispensing time has been correspondingly used for dispensing process but not for drug labeling. In contrast, there was a positive correlation only in TH. This special finding could be due to the TH pharmacists spending DT for not only for dispensing but for adequate drug labeling.

But we found drug labeling was reduced with increasing dispensing time in DH. Here the pharmacist in DH had strictly kept the DT as a fixed value by reducing the labeling when drug delivery was high.

All together we suggest that most of the pharmacist in government institutes had spent dispensing time for packing arrangements prior to delivery. Pharmacist in TH had spent time for improving basic information of drug to patient by labeling but not in GH or DH. This is not the accepted or recommended practice in a good dispensing system. Labelling had been reduced significantly when the number of dispensed drugs increases and we recommend health authorities to take precautions to prevent the incidence of undesirable adverse effects and high irrationality. Chances for patient to develop adverse drug reactions, poor therapeutic efficacy or even toxicity are comparatively higher in DH. We have published results of practicing polypharamcy in all three hospital categories and found that most of these prescriptions showed polypharmacy in addition to the poor labeling, we pointed out that the risk of drug interactions is also high.

Major reason for the malpractices in dispensing could be due to absence of a national drug policy and poor adherence to good pharmacy practice. On the other hand responsibilities of a pharmacist or a prescriber are not basically measured by the government authorities.

In addition to the above findings, NDAL and the NDP were significantly related only in TH showing that labeling was done for the drugs prescribed. But in contrast, we found pharmacists in DH and GH had reduced labeling when the number of prescription is high. This explains that dispensers in DH and GH had fixed their working time only for preparation of packets without concentrating on patient education on therapy.

Results of our study further showed an assessment on drug availability. We found that drug availability was 100% in DH and is low in both GH and TH (PDAD 97%, 94% respectively). We compared our PDAD values with other countries, Nigeria 70%[5] and Nepal 83%.[6] We understood that our values were higher than the values reported from most of the other countries (Cambodia,[7] Ethiopia[8] ranging from 82 to100%). Our high rate in PDAD can be explained by effective national drug policy in supply of medication for these government hospitals which is a mandatory factor for high quality patient care. We did not study the prescription analysis to see the defects and errors in concentration, dose, and dispensed medication, medication dispensed with a wrong pharmaceutical form. Therefore we have planned to identify the quantitative and qualitative prescription error analysis and also would expand our study to private pharmacies.

We would like to reiterate the need of proper training programme to improve the dispensing system in our country and the continuous monitoring system to evaluate the pharmacy practice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Action Program on Essential Drugs. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1995. How to investigate drug use in health facilities (Selected drug use indicators) p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hogerzeil HV, Walker GJ, Sallami AO, Fernando G. Impact of an essential drugs program on availability and rational use of drugs. Lancet. 1989;1:141–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91152-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrie JC, Grimshaw JM, Bryson A. The Scottish intercollegiate guidelines network initiative: Getting validated guidelines into local practice. Health Bull (Edinb) 1995;53:345–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otoro MJ, Dominguez-Gil A. Acountecimentos adversos por medicamentos: Unapatologia emergente. Farm Hosp. 2000;24:258–66. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bimo. Report on Nigeria field test. INRUD News. 1992;3:9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kafle KK and members of INRUD Nepal Core Group. INRUD drug use indicators in Nepal: Practice patterns in health posts in four districts. INRUD News. 1992;3:15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chareonkul C, Khun VL, Boonshuyar C. Rational drug use in Cambodia: Study of three pilot health centers in Kampong Thom Province. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2002;33:418–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desta Z, Abul T, Beyene L, Fantahun M, Yohannes AG, Ayalew S. Assessment of rational drug use an prescribing in primary health care facilities in north west Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 1997;74:758–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]