Abstract

Objective:

To identify the influence of catchment area, trauma center designation, hospital size, subspecialist employment, funding source, and other hospital characteristics on cyanide antidote stocking choice in US hospitals that provides emergency care.

Materials and Methods:

A web-based survey was sent out to pharmacy managers through two listservs; the American Society of Health-Systems Pharmacists and the American College of Clinical Pharmacy. A medical marketing company also broadcasted the survey to 2,659 individuals. We collected data on hospital characteristics (size, state, serving population, etc.,) to determine what influenced the hospital's stocking choice.

Results:

The survey response rate was approximately 10% (n = 286). Thirty-eight hospitals (16%) stocked at least 4 antidote kits. Safety profile, recommendations from a poison control center, and ease of use had the strongest influence on stocking decisions.

Conclusions:

Survey of 286 US hospital pharmacy managers, 38/234 (16%) hospitals had sufficient stocking of cyanide antidotes. Antidote preference was based on safety, ease of use, and recommendations by the local poison center, over cost.

Keywords: Antidotes, cyanide, pharmacies, poisoning, stocking

INTRODUCTION

Cyanide is a potent toxin that occurs in numerous forms causing harm if exposed by ingestion, inhalation, dermal absorption, or parenteral administration. It is used in mining, pest control, and industry. It contributes to smoke inhalation injury as the burning of plastics, silk, wool, and cotton releases hydrogen cyanide into fire smoke. It has been used as an agent for suicide, homicide, and terrorism.[1] In 2009, 238 exposures were reported to US poison control centers (PCC) and 70% of these were unintentional though it has the potential to be used as a chemical weapon.[2] Cyanide causes a shift towards cellular anaerobic metabolism, lactic acidosis, and rapid and severe central nervous system, cardiovascular, and respiratory toxic effects.[3] Because diagnosis is difficult, an antidote that is both effective and safe is desirable for empiric treatment. The three antidotes currently used in the United States are sodium thiosulfate (25% solution for injection), The cyanide antidote kit (CAK) (sodium nitrite and sodium thiosulfate), and hydroxocobalamin (CYANOKIT®). Their respective prices are approximately $20, $110, and $750. Sodium thiosulfate replaces depleted sulfate groups necessary for conversion of cyanide to thiocyanate, a less toxic and renally excreted compound.[4] Hydroxocobalamin binds directly to cyanide to form cyanocobalamin, which is non-toxic and excreted in the urine.[5]

Because cyanide is ubiquitous and is a frequent co-intoxication in victims of smoke inhalation, adequate hospital stocking of an effective antidote for cyanide intoxication is essential. Unfortunately, it is difficult to determine if hospitals stock sufficient quantities of an “appropriate” cyanide antidote because debate exists over which is more effective and safe.[6] Comparative data supporting one preferred antidote are low quality and limited. A recent animal study suggests that co-administration of hydroxocobalamin and sodium thiosulfate has similar early clinical improvement as sodium thiosulfate and sodium nitrite.[7] To date, no analysis has specifically analyzed cyanide antidote stocking, but several surveys have concluded that, in general, antidote stocking throughout North America is insufficient.[8–12]

Thus far, no published study has evaluated compliance of hospital cyanide antidote stocking levels with the 2009 expert consensus guidelines which recommends using two kits of hydroxocobalamin or one CAK to treat a 100 kg patient.[13] In addition to cyanide antidotes, the diverse panel of experts considered 24 antidotes for stocking and recommend that 12 be available for immediate administration. A rigid stocking recommendation for all hospitals may lead to insufficient stocking. Thus, the experts recommend that each hospital perform a hazard vulnerability assessment (HVA) to determine the amount of antidote to be stocked.[13] Factors to consider when assessing a hospital's need to stock antidotes include characteristics of the catchment area (industries, indigenous fauna, etc.,), history or experience of using the antidote, and anticipated time to restock the antidote. Hydroxocobalamin was designated as the preferred agent because of its wider application (smoke exposure), ease of use, and anticipated safety in widespread use, though both the CAK and hydroxocobalamin were recognized as acceptable.

The aim of our study was to survey pharmacies from US hospitals that provide emergency care, to determine which factors or barriers influence cyanide antidote stocking decisions, and to identify stocking patterns. Specifically, we sought to identify the influence of catchment area, trauma center designation, hospital size, clinical pharmacist and subspecialist employment, funding source, and other hospital characteristics on stocking choice and level. We also assessed the adherence to the 2009 Expert Consensus Guidelines for Stocking Antidotes in Hospitals that Provide Emergency Care.[13]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A web-based electronic survey was sent out to hospital pharmacy directors/managers at hospitals with an emergency department. Study participants were identified using two management listservs; the American Society of Health-Systems Pharmacists and the American College of Clinical Pharmacy. A medical marketing company was also used to broadcast the survey to 2,659 hospital pharmacy managers and directors throughout the US. The study was approved by Wilford Hall Medical Center's Institutional Review Board.

An electronic mail notification was delivered to the identified pharmacy director or manager with a study explanation and a hyperlink that directed the recipient to a 25-29 question survey. Informed consent was obtained when the participant selected the web-based survey hyperlink. An algorithm was used to route respondents to questions consistent with previous answers, thus survey length varied depending on responses. For instance, if a hospital only stocked hydroxocobalamin, the questionnaire would avoid any questions about stocking of sodium thiosulfate. The responses were anonymously collected by the electronic survey program (SurveyMonkey™) to which only the study investigators had access. Because the three databases overlap, participants received the survey more than once. We used two mechanisms to control for duplicate responses. The first was a question that automatically ended the survey if the participant responded that they had previously taken the survey. Also, the survey program automatically identified IP addresses and prevented a duplicate survey response from the same computer. Survey questions sought to determine hospital characteristics (size, state, serving population, funding source, burn center, etc.,), factors that influence a hospital's stocking choice (cost, familiarity, frequency of use, perceived effectiveness) and reasons why the alternative cyanide antidote was not stocked [Appendix 1]. The duplication of the databases led to a lower total response rate. We could not assess the true response rate but assume it is likely higher due to measuring duplicate recipients. In the United States, trauma centers are ranked and verified by the American College of Surgeons. We distinguished level I trauma centers from other hospitals because they provide comprehensive surgical care to trauma patients. These centers have a full range of specialists and equipment available 24 hours a day and admit a minimum number of severely injured patients annually. A verified burn center is a specific area within the hospital that has committed the resources necessary to meet the criteria for a burn center as determined by the American Burn Association and the American College of Surgeons. In addition to many other requirements, the area must contain beds and other equipment related to care of patients with burn injury.

The survey was pre-tested and internally validated for reliability by a medical toxicologist and three pharmacists. Responses were collected from 10 March 2010 to 15 June 2010. We attempted to increase response rate by broadcasting a reminder 14 days after the initial broadcast.

We used proportions and descriptive statistics for the statistical analysis. A 95 percent confidence interval was calculated for each proportion using the Wilson score method without continuity correction. The Newcombe-Wilson method without continuity correction was utilized to calculate a 95 percent confidence interval for the difference between two proportions.

RESULTS

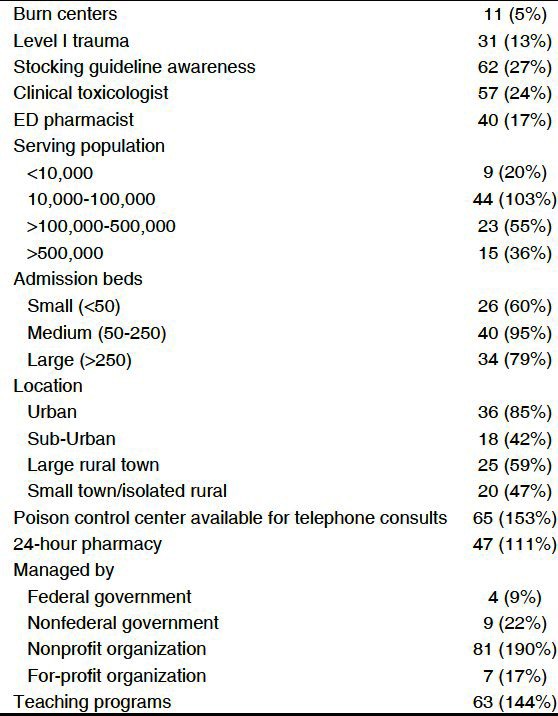

Two-hundred eighty six individuals responded to the survey out of approximately 2700 pharmacy personnel (10% response rate) submitted. There may have been some duplication of emails as we could not track how many were contacted by both the listserv and the email broadcast. Of the 286 respondents, 234 reported stocking cyanide antidote(s) at their institution. The CAK was stocked by most hospitals (61%, CI 0.55-0.67), hydroxocobalamin was stocked by 31% (CI 0.26-0.37) and sodium thiosulfate (for injection) in 13% (CI 0.09-0.18). Respondent demographics are represented in [Table 1].

Table 1.

Hospital characteristics (n=234)

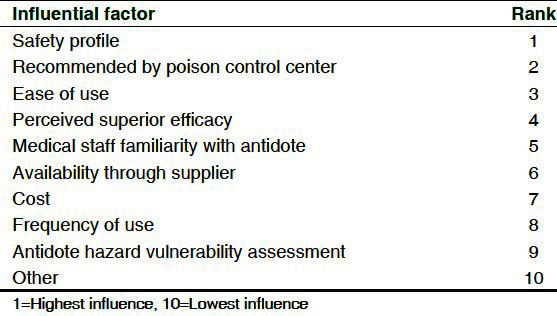

Sixty-two of 235 respondents (27%, CI 0.21 to 0.32) were aware of the 2009 expert consensus stocking guidelines. The same 62 individuals also reported that safety profile; recommendations from a PCC, and ease of use were the most influential in determining which antidote was stocked. Thirty-nine percent that were familiar with the guidelines felt that hydroxocobalamin was the best antidote for acute cyanide toxicity versus 46% for CAK (OR 1.49, 95% CI 0.72-3.05 of all survey respondents, 47% considered CAK the best, compared to 38% for hydroxocobalamin (OR 1.40, CI 0.95-2.07).

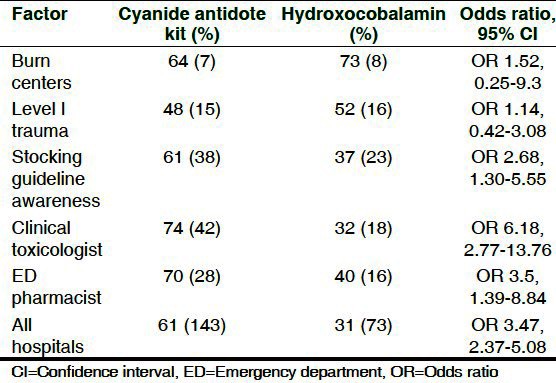

Thirty-eight pharmacists (16%) responded that their facility stocks at least 4 kits of either antidote option (antidote required to treat two 100 kg individuals) which was considered sufficient stocking amounts.[13] All of these 38 hospitals provided emergency care, 90% (CI 0.76-0.96) had at least 50 beds, 50% (CI 0.35-0.65) had at least 250 beds, and 61% (CI 0.45-0.74) served an urban area. Sixty-three percent (CI 0.47-0.77) of these facilities had a catchment population of at least 100,000 and 92% (CI 0.79-0.97) had a catchment population of at least 10,000. Although the institutions stocked at least four antidote kits, only 37% (CI 0.23-0.53) of these institutions had conducted a HVA for antidotes. In comparison, out of all survey respondents, only 21% had conducted a HVA for antidotes (OR 2.21, CI 1.07-4.49). The influence of various factors on antidote selection is represented in [Table 2].

Table 2.

Influence of factors on antidote selection

Stocking location and working hours of the pharmacy were surveyed to determine the accessibility of the antidote. The inpatient pharmacy (69%, CI 0.63-0.75) and the emergency department (63%, CI 0.57-0.69) were most common stocking locations. Thirty-eight percent (CI 0.32-0.44) of hospitals stocked cyanide antidotes in both the emergency department and the inpatient pharmacy and 40% (95% CI 0.34-0.46) of hospitals stocked antidotes in at least two different locations (emergency department, inpatient pharmacy, or some other location). Five institutions (2%, 95% CI 0.01-0.05) responded that antidotes were stocked by pre-hospital providers, on their ambulances. Cost was ranked 7 of 10 (1 was most influential) factors that influenced cyanide antidote stocking selection [Table 3].

Table 3.

Factors that influenced stocking selection

DISCUSSION

In our study, 16% of hospitals that provide emergency care had sufficient stocking of antidotes to treat two 100 kilogram patients. Previous studies that evaluated institutional antidote availability, reported that insufficient amounts are stocked. In 1996, a survey demonstrated that 24% of hospitals had inadequate stock of a cyanide antidote.[8] The authors of that study suggested that the lack of hospital resources and published guidelines may have contributed to stocking results. In 2003, a study that surveyed hospitals in Quebec reported that 68% complied with Canadian guidelines and 49% with US guidelines for stocking cyanide antidotes.[9] Though the 2003 survey reported insufficient antidote stocking, significant improvements were made compared to results from previous studies, including the 1996 study. Publication of stocking guidelines in 2000 may have contributed to this improvement.

Our study demonstrated that only 27% of respondents were aware of the current stocking guidelines and only 21% of respondents had conducted a hazard vulnerability assessment for antidotes. A higher proportion of institutions that stocked ≥ 4 kits of cyanide antidotes (recommended stocking levels) conducted a hazard vulnerability assessment (37%, OR 2.21, CI 1.07-4.49). This suggests that performing a risk assessment may encourage the hospital pharmacy manage to provide an adequate antidobte stock. We sought to assess adherence with the 2009 expert consensus stocking guidelines, although the recommendations are broad. The 2000 guidelines were more specific and recommended an amount of cyanide antidote necessary to treat two 70 kilogram patients for four hours.[12] In contrast, the current guidelines provide recommendations on the amount of each antidote needed to treat a 100 kg patient and do not specify the number of patients an institution should be prepared to treat. Instead of providing a minimum number of patients that need to be treated, the current 2009 consensus guidelines strongly recommend that each institution conduct a hazard vulnerability assessment that considers the risk and frequency of poisonings. For example, the number of individuals a hospital should expect to treat will be greater in an area where cyanide-containing reagents are frequently used such as mining. The institution-specific nature of the recommendations makes evaluating compliance with the guidelines difficult.

We also sought to identify if specific hospital characteristics influenced stocking choice. Nearly all hospitals had a similar preference for CAK, except for level I trauma centers and burn centers. Burn centers (71%) and level I trauma centers (52%) stocked more hydroxocobalamin than CAK or sodium thiosulfate for injection, although, not statistically significant. This is consistent with studies that report that hydroxocobalamin may be a better antidote for in smoke-inhalation and burn victims.[14] Survey participants ranked the influence of cost, medical staff familiarity with antidote, frequency of use, perceived superior efficacy, safety profile, availability through supplier, ease of use, recommendation by PCC, and antidote HVA on stocking decisions. Unexpectedly, cost had less influence on antidote choice which had been previously considered a barrier to hospital purchase of hydroxocobalamin.[14] Fewer adverse effects and ease of use were strong influential factors in our study and have been traditionally touted as the benefits of hydroxocobalamin.[7] Recommendation from PCC also ranked highly. This may reflect that more toxicologists and experts at poison centers are more comfortable using hydroxocobalamin and empirically find it easier to use, possibly reducing barriers to use.

Our study had several limitations. We conducted the study by survey and thus could not verify the respondents’ answers on stocking levels or demographics. Despite using an unrestricted sample size to maximize response rates, only 286 (~10%) responded to the survey and only 206 completed the survey in its entirety. We suspect the true response rate was higher. Ten percent is an approximation of the response rate because anonymity of listserv recipients prevented us from identifying duplications. Although, using listservs allowed our survey to reach more hospitals, it prevented us from accurately measuring the total number of hospitals that received the survey. However, a response of 206 US hospital pharmacies is large and captures a validated response to cyanide stocking in the United States. Another limitation is the potential bias that the survey responders were more likely to stock adequate antidote. Thus, our results may overestimate the national average of hospital with adequate cyanide antidote stock. We also surveyed only institutions that participate in selected listservs or only those that were previously identified by the contracted medical marketing service. In addition, selecting pharmacist or pharmacy managers as the survey recipient may introduce an additional bias as they may not be intimately involved the clinical services provided by the hospital and may not have provided accurate information on hospital demographics. However, hospital pharmacists were the most appropriate professionals to survey for information related to drug inventory and are able to easily obtain answers to hospital characteristics and HVA.

Although the survey design was internally validated, our survey instrument (SurveyMonkey™) was not pilot tested. Internal review was not sufficient to anticipate errors in the design of some questions, but this did not significantly impact our results. Lastly, the stocking patterns of sodium thiosulfate alone were assessed, but we did not report these results. Sodium thiosulfate is used for many indications (antineoplastic injection site extravasation, protection against cisplatin ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity,[15] and calciphylaxis/calcific uremic arteriolopathy,[16] thus reasons to stock this drug may not be limited to the treatment of cyanide toxicity.

Future studies may consider determining which factors prevented institutions from conducting an HVA as these factors are most likely to prevent compliance. Education on how to conduct an HVA is critical and/or development of tools to simplify these assessments may improve compliance.

CONCLUSION

In our survey of 286 US hospital pharmacy managers, 38/234 (16%) hospitals had sufficient stocking of cyanide antidotes. The CAK was stocked more often than hydroxocobalamin for cyanide toxicity; however the difference was not statistically significant. Most respondents preferred an antidote based on safety, ease of use, and recommendations by the local poison center, over cost as a factor. Hospital pharmacy managers that were aware of recently stocking guidelines or had conducted a HVA were more likely to stock sufficient cyanide antidotes. Future guidelines should continue to stress the importance of conducting a hospital-specific HVA and stocking adequate amount of antidote based on the assessment.

APPENDIX 1

-

Have you completed this survey before?

- Yes: □

- No: □

-

Are you the/a

- Pharmacist-in-charge: □

- Pharmacy Manager: □

- Pharmacy Director: □

- Staff Pharmacists: □

- Other (please specify): □

-

Which of the following apply to your hospital?

- Provides 24 hour emergency care: □

- Does not provide emergency care: □

- Provides emergency care, but for less than 24 hours/day. Please enter how many hours daily.

-

Approximately, how many Emergency Department visits does your facility have per year?

- ________________

-

Does your hospital employ or consult with a medical or clinical toxicologist (physician)?

- Yes: □

- No: □

- Unknown: □

-

Is there a clinical pharmacist staffed in your emergency department?

- Yes: □

- No: □

- Unknown: □

-

In which state is your hospital located?

- ________________

-

What is the hospitals approximate serving population (catchment area)?

- <10,000: □

- 10,000-100,000: □

- >100,000-500,000: □

- >500,000: □

- Unknown: □

-

How large is your hospital (Number of Admission Beds)?

- Small (<50 beds): □

- Medium (50-250 beds): □

- Large (>250 beds): □

- Unknown: □

-

In which setting is your hospital located?

- Urban Core (Contiguous area at least 50,000 people): □

- Sub-Urban (Approximately 30 -49% commute to urban core): □

- Large Rural Town (population of 10,000-49,000 with at least 10% commuting to urban core): □

- Small Town/Isolated Rural (population of less than 10,000): □

- Unknown: □

-

Select all that apply to your hospital

- Burn center: □

- Level I Trauma Center: □

- Level II Trauma Center: □

- Level III Trauma Center: □

- Pharmacist-manned 24-hour pharmacy: □

- Regional Poison Control Center is available for telephone consults: □

- None of the Above: □

-

The hospital is managed by the/a

- Federal government: □

- Nonfederal government: □

- Nonprofit organization: □

- For-profit organization: □

- Comments: ________________

-

Does your hospital have a teaching program for (Select all that apply)

- Medical residents: □

- Pharmacy residents: □

- Has no teaching program: □

- Unknown: □

- Other (please specify): ________________

-

Have you reviewed the American College of Emergency Physicians 2009 expert consensus guidelines for stocking antidotes?

- Yes: □

- No: □

- Unsure: □

-

Has your hospital developed an antidote hazard vulnerability assessment?

- Yes: □

- No: □

- Unknown: □

- Other: ________________

-

Where are cyanide antidotes stored? (Select all that apply)

- Inpatient Pharmacy: □

- Emergency Department: □

- Unknown: □

- Other location: □

-

Which of the following antidotes is/are currently stocked in your hospital?

- Hydroxocobalamin (Cyanokit®): □

- Sodium thiosulfate, amyl nitrite, sodium nitrite kit (Cyanide Antidote Kit®): □

- Sodium thiosulfate for injection alone (25% in 50 ml vials): □

- Other: ________________

- Multiple of the above antidotes: □

- Please explain if one of the last two answer choices was selected

- Other: ________________

-

How much Hydroxocobalamin is stocked in your hospital?

- 1 Kit (5 gm): □

- 2 Kits (10 gm): □

- 3 Kits (15 gm): □

- 4 kits (20 gm): □

- ≥5 kits (25 gm): □

- Unknown: □

- Not Applicable (Is not stocked): □

-

How many vials (2.5 grams) of hydroxocobalamin (for example) were administered in the last 12 months?

- ≤8 vials: □

- >8 vials, but ≤16 vials: □

- >16 vials, but ≤24 vials: □

- >24 vials, but ≤32 vials: □

- >32 vials: □

- Unknown: □

- Not Applicable (Is not stocked): □

-

How many sodium thiosulfate, amyl nitrite, sodium nitrite kits (Cyanide Antidote Kit®) are stocked in your hospital?

- 1 Kit (12.5 gm sodium thiosulfate): □

- 2 Kits (25 gm sodium thiosulfate): □

- 3 Kits (37.5 gm sodium thiosulfate): □

- 4 kits (50 gm sodium thiosulfate): □

- ≥5 kits (62.5 gm sodium thiosulfate): □

- Unknown: □

- Not Applicable (Is not stocked): □

-

How many sodium thiosulfate, amyl nitrite, sodium nitrite kits (Cyanide Antidote Kit®) were administered in the last 12 months?

- <4 kits: □

- >4 kit, but ≤8 kits: □

- >8 kits, but ≤12 kits: □

- >12 kits, but ≤16 kits: □

- >16 kits: □

- Unknown: □

- Not Applicable (Is not stocked): □

-

How much sodium thiosulfate for injection alone (25% in 50 ml vials) is stocked in your hospital?

- 1 Vial (12.5 gm): □

- 2 Vials (25 gm): □

- 3 Vials (37.5 gm): □

- 4 Vials (50 gm): □

- ≥5 Vials (62.5 gm): □

- Unknown: □

- Not Applicable (Is not stocked): □

-

How much sodium thiosulfate for injection alone (25% in 50 ml vials) were administered in the last 12 months?

- <4 Vials: □

- >4 Vials, but ≤8 Vials: □

- >8 Vials, but ≤12 Vials

- >12 Vials, but ≤16 Vials: □

- >16 Vials: □

- Unknown: □

- Not Applicable (Is not stocked): □

-

How much Hydroxocobalamin is stocked in your hospital?

- 1 Kit (5 gm): □

- 2 Kits (10 gm): □

- 3 Kits (15 gm): □

- 4 kits (20 gm): □

- ≥5 kits (25 gm): □

- Unknown: □

-

How many vials (2.5 grams) of hydroxocobalamin (for example) were administered in the last 12 months?

- ≤8 vials: □

- >8 vials, but ≤16 vials: □

- >16 vials, but ≤24 vials: □

- >24 vials, but ≤32 vials: □

- >32 vials: □

- Unknown: □

-

How many sodium thiosulfate, amyl nitrite, sodium nitrite kits (Cyanide Antidote Kit®) are stocked in your hospital?

- 1 Kit (12.5 gm sodium thiosulfate): □

- 2 Kits (25 gm sodium thiosulfate): □

- 3 Kits (37.5 gm sodium thiosulfate): □

- 4 kits (50 gm sodium thiosulfate): □

- ≥5 kits (62.5 gm sodium thiosulfate): □

- Unknown: □

-

How many sodium thiosulfate, amyl nitrite, sodium nitrite kits (Cyanide Antidote Kit®) were administered in the last 12 months?

- <4 kits: □

- >4 kit, but ≤8 kits: □

- >8 kits, but ≤12 kits: □

- >12 kits, but ≤16 kits: □

- >16 kits: □

- Unknown: □

-

How much sodium thiosulfate for injection alone (25% in 50 ml vials) is stocked in your hospital?

- 1 Vial (12.5 gm): □

- 2 Vials (25 gm): □

- 3 Vials (37.5 gm): □

- 4 Vials (50 gm): □

- ≥5 Vials (62.5 gm):

- Unknown: □

-

How much sodium thiosulfate for injection alone (25% in 50 ml vials) were administered in the last 12 months?

- <4 Vials: □

- >4 Vials, but ≤8 Vials: □

- >8 Vials, but ≤12 Vials: □

- >12 Vials, but ≤16 Vials: □

- >16 Vials: □

- Unknown: □

-

When was the last time a cyanide antidote was administered at your hospital?

- ≤1 month: □

- >1 month, but ≤6 months: □

- >6 months, but ≤12 months: □

- >12 months: □

- Unknown: □

- Please specify other: ________________

-

How many times in the last 3 yrs was a cyanide antidote dispensed for possible cyanide toxicity in your hospital?

- ________________

-

Which of the following factors influenced your decision to stock hydroxocobalamin? Please rank. (10 being most influential, 1 being least influential)

- Least Influential: 1

- Most Influential: 10

- Cost: □

- Medical staff familiarity with antidote: □

- Frequency of use: □

- Perceived superior efficacy: □

- Safety profile: □

- Availability through supplier: □

- Ease of Use: □

- Recommended by Poison Control Center: □

- Antidote Hazard Vulnerability Assessment: □

- Other: □

-

Which of the following influenced your decision to stock your current antidote(s)? (Select all that apply)

- Cost: □

- Frequency of Use: □

- Availability through supplier: □

- Staff's lack of familiarity: □

- Safety profile: □

- Comparative efficacy: □

- Difficult to use: □

- Not Recommended by the Poison Control Center: □

- Antidote Hazard Vulnerability Assessment: □

- Other (please specify): □

-

Which of the following hazard vulnerability assessment criteria would apply to your hospital? (Select all that apply)

- Local industries generate cyanide: □

- Nearby chemical transportation routes: □

- Possible use of cyanide baits for agriculture: □

- Popularity and history of cyanide as a suicide agent: □

- High frequency of fires involving multiple casualties: □

- Hospital provides tertiary treatment (receives referrals from remote areas): □

- Prolonged periods before restocking of cyanide antidotes: □

- Unknown, hazard assessment not performed: □

-

Based on cost, adverse effects, published data, and effectiveness which antidote do you feel is best for acute cyanide toxicity?

- Hydroxocobalamin (Cyanokit®): □

- Sodium thiosulfate, amyl nitrite, sodium nitrite kit (Cyanide Antidote Kit®): □

- Sodium thiosulfate for injection alone (25% in 50 mL vial): □

- Other (please specify): □

-

Additional Comments:

________________

Footnotes

Source of Support: The research was funded by the Surgeon General's Office (SG) Funding Support for Research Grant #FWH20100067E

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eckstein M. Enhancing public health preparedness for a terrorist attack involving cyanide. J Emerg Med. 2008;35:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Jr, Green JL, Rumack BH, Giffin SL. 2008 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 26th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol. 2009;47:911–1084. doi: 10.3109/15563650903438566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holstege CP, Isom GE, Kirk MA. Cyanide and Hydrogen Sulfide. In: Flomenbaum NE, Goldfrank LN, Hoffman RS, Howland MA, Lewin NA, Nelson LS, editors. Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2002. pp. 1712–21. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen KK, Rose CL. Nitrite and thiosulfate therapy in cyanide poisoning. J Am Med Assoc. 1952;149:113–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.1952.02930190015004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ries NL, Dart RC. New developments in antidotes. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89:1379–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall AH, Dart RC, Bogdan G. Sodium thiosulfate or hydroxocobalamin for the empiric treatment of cyanide poisoning? Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:806–13. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bebarta VS, Tanen DA, Lairet J, Dixon PS, Valtier S, Bush A. Hydroxocobalamin and sodium thiosulfate versus sodium nitrite and sodium thiosulfate in the treatment of acute cyanide toxicity in a swine (Sus scrofa) model. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:345–51. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dart RC, Stark Y, Fulton B, Koziol-McLain J, Lowenstein SR. Insufficient Stocking of Poisoning Antidotes in Hospital Pharmacies. JAMA. 1996;276:1508–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey B, Bussieres JF, Dumont M. Availability of antidotes in Quebec hospitals before and after dissemination of guidelines. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003;60:2345–9. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/60.22.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teresi WM, King WD. Survey of the stocking of poison antidotes in Alabama hospitals. South Med J. 1999;92:1151–6. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199912000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woolf AD, Chrisanthus K. On-Site Availability of Selected Antidotes: Results of a Survey of Massachusetts Hospitals. Am J Emerg Med. 1997;15:62–6. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(97)90051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dart RC, Goldfrank LR, Chyka PA, Lotzer D, Woolf AD, McNally J, et al. Combined evidence-based literature analysis and consensus guidelines for stocking of emergency antidotes in the United States. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:126–32. doi: 10.1067/mem.2000.108182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dart RC, Borron SW, Caravati EM, Cobaugh DJ, Curry SC, Falk JL, et al. Expert consensus guidelines for stocking of antidotes in hospitals that provide emergency care. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:386–94. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shepherd G, Velez LI. Role of hydroxocobalamin in acute cyanide poisoning. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:661–9. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sodium Thiosulfate. In DRUGDEX® System. Thomson Healthcare. [Last accessed on 2010 Jul 15]. Available from: http://www.thomsonhc.com .

- 16.Hayden MR, Goldsmith DJ. Sodium thiosulfate: New hope for the treatment of calciphylaxis. Semin Dial. 2010;23:258–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2010.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]