Abstract

Tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF) is endemic in mountainous regions of the western United States. In California, the principal agent is the spirochete Borrelia hermsii, which is transmitted by the argasid tick Ornithodoros hermsi. Humans are at risk of TBRF when infected ticks leave an abandoned rodent nest in quest of a blood meal. Rodents are the primary vertebrate hosts for B. hermsii. Sciurid rodents were collected from 23 sites in California between August, 2006, and September, 2008, and tested for serum antibodies to B. hermsii by immunoblot using a whole-cell sonicate and a specific antigen, glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase (GlpQ). Antibodies were detected in 20% of rodents; seroprevalence was highest (36%) in chipmunks (Tamias spp). Seroprevalence in chipmunks was highest in the Sierra Nevada (41%) and Mono (43%) ecoregions and between 1900 and 2300 meters elevation (43%). The serological studies described here are effective in implicating the primary vertebrate hosts involved in the maintenance of the ticks and spirochetes in regions endemic for TBRF.

Key Words: Borrelia hermsii, Tick-borne relapsing fever, Rodentia

Introduction

Tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF) is a bacterial illness caused by spirochetes of the genus Borrelia. Persons suffering from TBRF typically experience episodes of fever and other nonspecific symptoms, such as headache, body ache, and abdominal complaints. Febrile episodes are usually 3–7 days in duration and separated by 3–5 days of defervescence and apparent recovery. Patients typically respond well to treatment with antibiotics, but untreated patients may suffer up to 13 febrile episodes (Southern and Sanford 1969). Severe complications, including acute respiratory distress syndrome, meningitis, and death of infants infected in utero, have been rarely reported (Fuchs and Oyama 1969, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1990, 2007, Dworkin et al. 1998).

Borrelia hermsii is the primary etiologic agent of TBRF in the western United States and is transmitted by the hematophagous argasid tick Ornithodoros hermsi. The primary hosts for these ticks are rodents. Nearly 100 native species of rodent occur in California (California Department of Fish and Game 2008), of which many members of the families Sciuridae (e.g, Tamias spp., Otospermophilus) and Cricetidae (e.g., Neotoma spp., Peromyscus spp.) are habituated to human activity and frequently nest near or within buildings. When rodents abandon nests in buildings, extant ticks may seek out other mammals, including humans, upon which to feed. Because O. hermsi feed at night, have a painless bite, and attach for only 10–60 min, most TBRF patients do not recall a tick bite. The classic exposure for TBRF occurs while sleeping in a cabin located between 600 and 2200 meters elevation (Dworkin et al. 2008).

In addition to being the principal feeding host for the tick vector, rodents are also important hosts for the horizontal maintenance of B. hermsii. Tamias amoenus, Tamiasciurus hudsonicus, and Microtus pennsylvanicus were able to sustain spirochetemia following experimental inoculation with B. hermsii (Burgdorfer and Mavros 1970). However, natural infections with B. hermsii have been reported for only a few species of rodents sampled in select locations. Field studies in 1931 and 1932 at Packer Lake, Lake Tahoe, and Big Bear Lake in California found active spirochete infections in chipmunks (Tamias spp.) and Douglas (Tamarck) tree squirrels (Tamiasciurus douglasii) (Porter et al. 1932). PCR failed to detect B. hermsii infection in sera from 168 Tamias sp. and 12 Tamiasciurus sp. collected in northeastern California (Cleary and Theis 1999). Among rodents collected at sites of California TBRF cases, 36% of T. amoenus in northern California and 40% of Peromyscus boylii in southern California had serum antibodies to glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase (GlpQ), a protein antigen highly specific for relapsing fever group Borrelia (RFGB) (Schwan et al. 1996, Schwan et al. 2009, Fritz et al. 2004).

From 1970 to 2010, 336 cases of TBRF were reported in California. Over half of the cases of TBRF in California were likely exposed in 4 regions in the Sierra Nevada Mountains (Lake Tahoe, Mammoth Lakes, Huntington Lake) and the San Bernardino Mountains (Big Bear Lake). Much of these areas are within or adjacent to land under federal jurisdiction, including recreational areas under the administration of the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service (USFS) and U.S. Department of Interior National Park Service (NPS). Evidence of rodent activity and ingress, particularly deer mice, was previously documented in and around California USFS facilities (Levine et al. 2008). Staff and visitors may be at risk of contracting TBRF if they sleep in cabins, barracks, or other buildings that currently or formerly harbor rodents. The objective of this project was to determine the presence of B. hermsii in rodents around buildings maintained on USFS/NPS properties by testing the animals for antibodies produced in response to infection with RFGB. The ultimate goal of this project was to assess the risk of TBRF at USFS/NPS facilities and to identify appropriate corrective and preventive actions to mitigate that risk.

Materials and Methods

Facilities on USFS/NPS lands were selected for study based on either having a history of TBRF cases that were believed to have been exposed there, or being located in areas with environmental features similar to known TBRF risk areas (e.g., coniferous forest above 600 meters elevation). Additional sites were included in response to specific requests from USFS/NPS personnel to evaluate facilities with a suspected or recognized rodent problem. Georeferencing points were used to categorize sites according to USFS Ecologic Region Sections and Sub-sections (www.fs.fed.us/r5/projects/ecoregions/toc.htm/).

Active rodent populations at each project site were evaluated through live trapping. Sherman live traps (H.B. Sherman, Tallahassee, Florida) baited with rolled oats were deployed for surveillance of nocturnal sigmodontine rodents and Tomahawk live traps (Tomahawk Live Trap Co., Tomahawk, Wisconsin) baited with peanut butter and rolled oats for diurnal sciurid rodents. Between 20 and 120 traps, depending on facility size, were set in and around buildings for each trapping effort. Captured rodents were anesthetized with ethyl ether or isoflurane, identified to species and sex, and examined for ectoparasites. A sample of blood was collected by micropipette from the retrobulbar sinus or by intracardiac puncture. Rodents were released near their point of capture following recovery from anesthesia.

Serum samples were tested (1:100 dilution) by immunoblot with whole-cell lysates of B. hermsii strain DAH and purified recombinant GlpQ, as previously described (Schwan et al. 1996). GlpQ is an immunodominant protein in RFGB but absent from B. burgdorferi sensu lato and allows for the serological discrimination between animals previously infected with relapsing fever spirochetes versus Lyme disease spirochetes (Schwan et al. 1996). This assay has been used previously to test rodent serum samples collected during investigations of the putative sites where TBRF patients were exposed in California (Fritz et al 2004, Schwan et al. 2009). In the present study, a serum sample was considered positive if it contained antibodies that bound to 8 or more proteins in the B. hermsii whole-cell lysate and also bound to the purified GlpQ. Serum samples from infected and uninfected laboratory mice were included at the same 1:100 dilution and served as positive and negative controls for the immunoblots.

Results

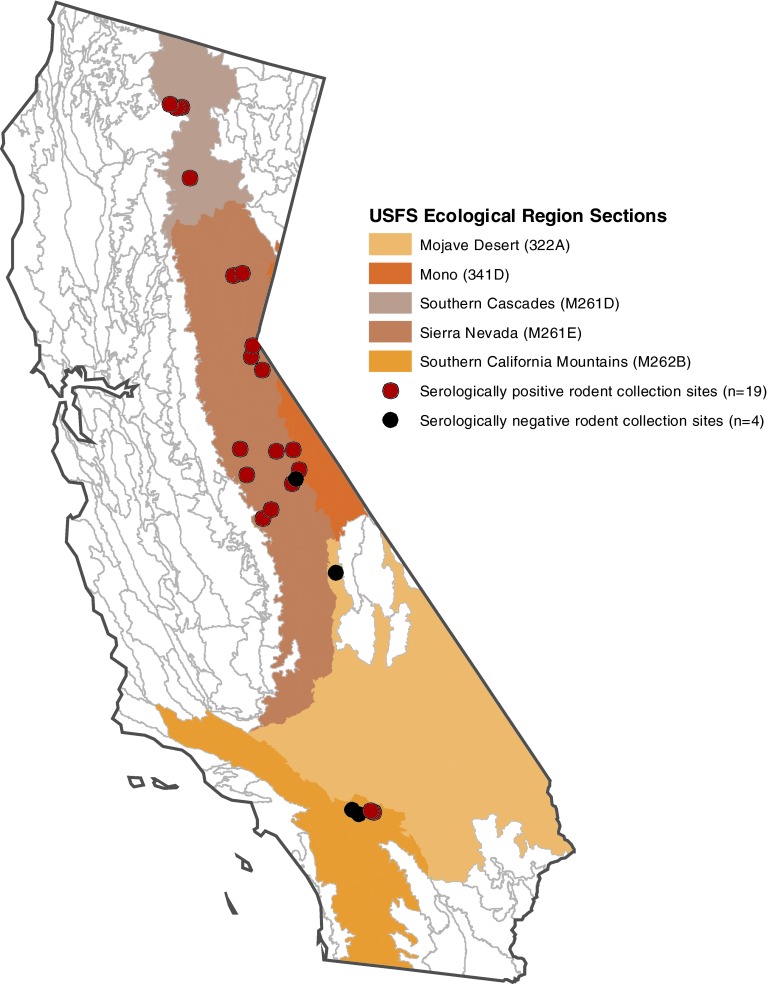

Eighteen sites in 7 USFS units and 5 sites at 3 NPS units were studied between August, 2006, and September, 2008. Project sites were 7 campgrounds, 4 ranger stations, 4 fire stations, 3 private residences, 2 visitor centers, 1 fire lookout, 1 guest lodging, and 1 staff housing. Five Ecologic Sections were represented in the study: Sierra Nevada (12 sites), Southern Cascades (4), Southern California Mountains (4), Mono (2), and Mojave Desert (1)(Fig. 1). Sites ranged from 975 to 2774 meters elevation.

FIG. 1.

Ecological regions and sampling locations for wild rodents tested for serum antibodies to relapsing-fever group Borrelia in California during 2006–2008.

Blood specimens were collected and tested from 480 rodents (Table 1). The number of rodents sampled at each site ranged from 1 to 54. At least 22 species of rodents were sampled, representing 4 families: 304 Sciuridae (Sciurus sp., Otospermophilus sp., Callospermophilus sp., Tamias spp.), 174 Cricetidae (Microtus spp., Neotoma spp., Peromyscus spp.), 1 Heteromyidae (Dipodomys sp.), and 1 Dipodidae (Zapus sp.).

Table 1.

Serum Antibodies to Relapsing Fever Group Borrelia in Rodents, California

| Rodent species | No. seropositive/No. collected | % |

|---|---|---|

| Family Sciuridae | ||

| Callospermophilus lateralis | 3/26 | 11.5 |

| Otospermophilus beecheyi | 15/61 | 24.6 |

| Sciurus griseus | 1/3 | 33.3 |

| Tamias amoenus | 34/72 | 47.2 |

| Tamias merriami | 4/19 | 21.1 |

| Tamias quadrimaculatus | 4/7 | 57.1 |

| Tamias senex | 4/20 | 20.0 |

| Tamias speciosus | 27/83 | 32.5 |

| Tamias umbrinus | 0/1 | 0.0 |

| Tamiasciurus douglasii | 1/12 | 8.3 |

| Family Cricetidae | ||

| Microtus californicus | 0/1 | 0.0 |

| Microtus montanus | 0/7 | 0.0 |

| Neotoma cinerea | 0/4 | 0.0 |

| Neotoma fuscipes | 1/7 | 14.3 |

| Neotoma lepida | 0/8 | 0.0 |

| Peromyscus boylii | 0/2 | 0.0 |

| Peromyscus californicus | 0/1 | 0.0 |

| Peromyscus eremicus | 0/4 | 0.0 |

| Peromyscus maniculatus | 2/133 | 1.5 |

| Peromyscus truei | 0/5 | 0.0 |

| Peromyscus sp. | 0/2 | 0.0 |

| Family Dipodidae | ||

| Zapus princeps | 0/1 | 0.0 |

| Family Heteromyidae | ||

| Dipodomys sp. | 0/1 | 0.0 |

Antibodies to RFGB were detected in 96 (20%) specimens. At least 1 seropositive rodent was identified in 11 of 22 species tested. Serum antibodies to RFGB were rare among Cricetidae (3 of 174, 1.7%) and absent from the single Heteromyidae and Dipodidae specimens. Serum antibodies were detected in 93 of 304 (31%) Sciuridae rodents: 73 of 202 (36%) chipmunks (T. amoenus, T. merriami, T. quadrimaculatus, T. senex, T. speciosus, T. umbrinus), 18 of 87 (21%) ground squirrels (Otospermophilus beecheyi, Callospermophilus lateralis), and 2 of 15 (13%) other sciurids (Sciurus griseus, T. douglasii). Among Sciuridae, seroprevalence was highest in Tamius quadrimaculatus (4 of 7, 57%) and lowest in Tamius umbrinus (0 of 1, 0%), although few individuals of these species were sampled. As 96% of chipmunks and ground squirrels were adults, stratification of seroprevalence by age was not performed.

Sixty-two of 150 (41%) chipmunks collected above 1900 meters elevation were seropositive compared to 11 of 52 (21%) chipmunks collected below 1900 meters. Seroprevalence among chipmunks was highest (36 of 84, 43%) for those collected between 1900 and 2300 meters elevation. Although seropositive chipmunks were prevalent above 2200 meters elevation (30 of 76, 39%), seropositive ground squirrels were rare at this elevation (1 of 10, 10%). Of the 18 seropositive ground squirrels, 17 were collected between 1200 and 2200 meters elevation (17 positive of 72 tested, 23%). Seroprevalence among ground squirrels was highest (16 of 48, 33%) for those animals collected between 1685 and 1913 meters elevation.

At least 1 seropositive rodent was collected at 19 of the 23 study sites. At 11 sites where both chipmunks and ground squirrels were collected, RFGB antibodies were detected in both chipmunks and ground squirrels at 3 sites, in only chipmunks at 6 sites, and in only ground squirrels at 2 sites. The seroprevalence for chipmunks and ground squirrels combined was highest at 1 site in the USFS Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit (26 of 42, 62%).

Serum antibodies were nearly twice as prevalent in chipmunks collected in the Sierra Nevada (63 of 156, 40%) and Mono (3 of 7, 43%) Ecologic Sections as chipmunks sampled in the Southern California Mountains (4 of 19, 21%) and 3 times as prevalent as chipmunks sampled in the Southern Cascades (3 of 20, 15%; Table 2). Serum antibodies in ground squirrels were more than twice as prevalent in those collected in the Sierra Nevada (17 of 76, 22%) compared to all other Ecologic Sections (1 of 11, 9%). Tahoe Valley was the Ecologic Subsection in which serum antibodies were most prevalent for both chipmunks (22 of 34, 65%) and ground squirrels (5 of 11, 45%).

Table 2.

Serum Antibodies to Relapsing Fever Group Borrelia in Rodents, California

|

USFS EcoRegion |

|

|

No. samples positive/Total no. samples (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section / Subsection | Jurisdictiona | Elevation (m) | Chipmunksb | Ground squirrelsc | Other rodents | |||

| Mojave Desert (322A) | ||||||||

| Owens Valley | Manzanar NHS | 1162 | 0 | — | 0/2 | (0) | 0/12 | (0) |

| Mono (341D) | ||||||||

| Glass Mountain | Inyo NF | 2298 | 3/7 | (43) | 0/1 | (0) | 0/4 | (0) |

| Sierra Nevada (261E) | ||||||||

| Lower Batholith | Yosemite NP | 1207 | 0 | — | 1/4 | (25) | 0 | — |

| Batholith and Volcanic Flows | Yosemite NP | 1445 | 1/1 | (100) | 0/10 | (0) | 0/1 | (0) |

| Lower Batholith | Sierra NF | 1685 | 0/2 | (0) | 8/17 | (47) | 0/4 | (0) |

| Upper Batholith and Volcanic Flows | Tahoe NF | 1685 | 4/13 | (31) | 0 | — | 0/15 | (0) |

| Eastern Slopes | Humboldt-Toiyabe NF | 1793 | 2/14 | (14) | 2/19 | (10) | 0/7 | (0) |

| Frenchman | Tahoe NF | 1811 | 1/2 | (50) | 0 | — | 0/4 | (0) |

| Tahoe Valley | Lake Tahoe Basin MU | 1913 | 21/31 | (68) | 5/11 | (45) | 0/11 | (0) |

| Upper Batholith | Sierra NF | 2130 | 7/24 | (29) | 0/6 | (0) | 1/19 | (5) |

| Eastern Slopes | Inyo NF | 2189 | 7/12 | (58) | 0 | — | 0/42 | (0) |

| Tahoe Valley | Lake Tahoe Basin MU | 2269 | 1/3 | (33) | 0 | — | 0/1 | (0) |

| Eastern Slopes | Inyo NF | 2438 | 0/3 | (0) | 0 | — | 0/2 | (0) |

| Glaciated Batholith | Yosemite NP | 2620 | 9/20 | (45) | 1/5 | (20) | 0/23 | (0) |

| Glaciated Batholith | Inyo NF | 2774 | 10/31 | (32) | 0/4 | (0) | 1/2 | (50) |

| Southern California Mountains (M262B) | ||||||||

| Upper San Gorgonio Mountains | San Bernardino NF | 1707 | 0 | — | 0 | — | 0/3 | (0) |

| Upper San Gorgonio Mountains | San Bernardino NF | 1829 | 0 | — | 0 | — | 0/8 | (0) |

| Upper San Gorgonio Mountains | San Bernardino NF | 2081 | 0/5 | (0) | 0 | — | 1/5 | (20) |

| Upper San Gorgonio Mountains | San Bernardino NF | 2084 | 4/14 | (29) | 0 | — | 2/27 | (7) |

| Southern Cascades (M261) | ||||||||

| Hat Creek Rim | Shasta-Trinity NF | 975 | 1/6 | (17) | 0/1 | (0) | 0 | — |

| Hat Creek Rim | Shasta-Trinity NF | 1006 | 1/1 | (100) | 0 | — | 0 | — |

| Hat Creek Rim | Shasta-Trinity NF | 1123 | 1/8 | (12) | 0/2 | (0) | 0 | — |

| Lassen-Almanor | Lassen Volcanic NP | 1802 | 0/5 | (0) | 1/5 | (20) | 0 | — |

| Total | 73/202 | (36) | 18/87 | (21) | 5/191 | (3) | ||

MU, Management Unit; NF, National Forest; NP, National Park; NHS, National Historic Site.

Tamias amoenus, T. merriami, T. quadrimaculatus, T. senex, T. speciosus, T. umbrinus.

Otospermophilus beecheyi, Callospermophilus lateralis.

Discussion

This study represents the most extensive report of RFGB serology in rodents across species, geographic range, and ecologic habitats in any region of the western United States. Serum antibodies to RFGB were detected in ground squirrels, tree squirrels, mice, woodrats, and chipmunks, representing 11 species from 2 families. At least 1 seropositive rodent was identified in 4 major ecologic regions and throughout the elevation range of the study (975 to 2774 meters).

Seroprevalence to RFGB was highest (36%) in chipmunks (Tamias spp.). Antibodies to RFGB were detected in at least 1 chipmunk at 15 of 19 study sites, representing 4 ecologic regions, and in 6 of 7 species of chipmunk sampled. RFGB antibodies were not detected in the single specimen of T. umbrinus; however, 3 of 6 T. amoenus collected at the same location as the T. umbrinus specimen were seropositive. Seroprevalence was highest (57%) for T. quadrimaculatus, but as only 7 specimens were collected from 4 different sites, it is uncertain how representative this estimate is. Both sample sizes and seroprevalence estimates were greatest for T. amoenus (47%) and T. speciosus (33%). Serum antibodies to RFGB were previously detected in 36% of T. amoenus collected in the investigation of 9 human cases of TBRF associated with a single cabin in northern California (Fritz et al. 2004).

Serum antibodies to RFGB were detected in only 21% of ground squirrels and at less than half of the study sites where ground squirrels were sampled. No clear association was evident between seroprevalences in ground squirrels and chipmunks, suggesting that transmission of RFGB may occur independently in these rodent groups. The more restricted distribution, lower seroprevalence, and lesser proclivity to invade and nest in buildings suggest that ground squirrels' direct contribution to RFGB transmission to humans is less important than other rodents. Ground squirrels may serve as a principal feeding host for O. hermsi and contribute to maintaining tick population density but only be incidentally infected with B. hermsii.

Pine and Douglas squirrels (Tamiasciurus spp.) have been noted as abundant and/or invasive at implicated sites of exposure in previous investigations of TBRF cases (Thompson et al. 1969, Edell et al. 1979, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1990, 2003, Fritz et al. 2004). Only 12 Douglas squirrels (T. douglasii) were collected and tested in the present study; 9 of these animals were collected from only 2 sites and during the same month of the study. A more geographic and seasonally extensive survey of Douglas squirrels might better estimate their infection prevalence and better elucidate their role, if any, in TBRF ecology.

In the present study, evidence of RFGB infection was rare in mice and rats. Antibodies to RFGB were detected in a small percentage of Peromyscus mice (2 of 155, 1.3%). Murid rodents have an affinity for human habitations, and their access points and nests in buildings could be used by other rodents. A chipmunk carcass was recovered from a wood rat nest in a cabin implicated as the exposure site for 9 TBRF cases in northern California (Fritz et al. 2004). In a review of 182 TBRF cases reported in Washington, Idaho, and Oregon, case-patients more frequently reported seeing mice (41%) than squirrels (35%) or chipmunks (30%) at the implicated exposure sites (Dworkin et al. 1998). While extensive comparable serologic surveillance of mice in the northwestern United States has not been conducted, Peromyscus and other Cricetidae rodents may have a more significant role in the ecology of TBRF in these northern latitudes than in California.

TBRF in the western United States is typically associated with exposure at higher elevations. Published epidemiologic studies and outbreak investigations suggest that TBRF exposure in California and the southwestern United States may occur at higher elevations than in the northwestern states. Outbreaks reported from Washington and Montana occurred at elevations of 945 and 1000 meters, respectively (Thompson et al. 1969, Schwan et al. 2003); however, the largest reported outbreak of TBRF in the United States occurred in the Southwest, on the north rim of the Grand Canyon in Arizona, at 2560 meters elevation (Boyer et al. 1977). In a review of cases reported in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and British Columbia, the median elevation at exposure sites was 650 meters (range, 30–1960 meters) (Dworkin et al. 1998). In contrast, of 69 TBRF cases reported in California between 1998 and 2010 for which likely site of exposure could be reliably determined, 58 cases (84%) were likely exposed at sites above 1900 meters (range, 1065–2743 meters) (California Department of Public Health, unpublished data). In the present study, serum antibodies to RFGB were detected in 40% of chipmunks and 22% of ground squirrels collected above 1900 meters. At the highest elevations (>2400 m), which include 12% of TBRF case exposure sites, seroprevalence remained high in chipmunks (19 of 54, 35%) but was low for ground squirrels (1 of 9, 11%). Seropositive chipmunks were identified between 975 and 2774 meters elevation, whereas 89% of seropositive ground squirrels were collected from a lower and narrower range of 1685–1913 meters. The comparatively greater abundance and seroprevalence across a broader elevation range suggest that the role of chipmunks in TBRF maintenance and transmission at higher elevations may be more significant than that of other rodents.

Seropositive chipmunks and squirrels were most commonly observed in the Sierra Nevada Ecologic Section. The Sierra Nevada section encompasses 20,282 square miles of the western Sierra Nevada mountain range in California. Vegetation consists chiefly of ponderosa pine and fir-spruce, providing forage and harborage for ground-dwelling and arboreal rodents. Precipitation ranges from 50 to >200 cm per year, mostly in the form of winter snow, with species of rodents entering a winter hibernation or torpid state with occasional periods of activity. The dry, mild (5–15°C) summers may decrease mortality from environmental causes (e.g., desiccation, fungal infections) in nest-dwelling Ornithodoros ticks, thereby enhancing their opportunity to transmit RFGB to multiple individuals and generations of rodents compared to lower, warmer regions where precipitation is chiefly in the form of rain. Nevertheless, the Sierra Nevada Ecological Section was oversampled in this study and the ecology of rodents and RFGB in other environments—such as Mono, Southern California Mountains, and Southern Cascades Sections where seropositive rodents were also found—awaits more extensive study.

Rodents serve as primary hosts for both B. hermsii and the tick vector. However, B. hermsii have been infrequently observed in rodents collected during TBRF case investigations (Porter et al 1932, Trevejo et al 1998). Spirochetemia in rodents likely mimics the transient and cyclical pattern observed in human TBRF patients. Experimental inoculation with B. hermsii led to fatal disease and up to 30 days of detectable spirochetemia in pine squirrels (T. hudsonicus), but chipmunks had detectable spirochetemia for less than 7 days and no clinical signs of disease (Burgdorfer and Mavros 1970). The immunokinetics of RFGB antibodies and its correlation to spirochetemia in wild rodents are unknown. If chipmunks are significant hosts for RFGB, the transient spirochetemia, combined with the infrequent feeding habits of Ornithodoros ticks, suggest that heavy and persistent densities of ticks in rodent nests are necessary for enzootic transmission.

TBRF patients are typically infected with B. hermsii while sleeping in buildings in which wild rodents have established, and then abandoned, nests containing infectious ticks. Secondary to this study, investigators identified structural breaches in physical facilities at several study sites that could serve as ingress points for wild rodents. The defects most frequently observed were unsealed conduits, commonly around dryer vents, or crawl spaces under the building. Many woodpecker holes and knotholes were also observed in the sides of buildings.

TBRF is a rare, but serious, disease that can be contracted in many montane areas of California. The widespread detection of RFG antibodies in this study substantiates that B. hermsii is present and infects rodents over a broad geographic range of California. Therefore, anyone working and living in areas with increased exposure potential, such as USFS/NPS employees, should be made aware of the risks and educated about means to mitigate them. High seroprevalence, small size, predisposition to nest in buildings, broad geographic distribution, and habituation to human activity all contribute to chipmunks as the rodent of most concern for TBRF. A comprehensive and effective prevention program for TBRF includes the application of aerosol acaricides to the tick-infested buildings, elimination of existing rodents and rodent nests, exclusion of rodents, reduction of incentives for rodents, appropriate maintenance of buildings, and education of staff, guests, and others about actions to reduce their individual risk of exposure.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Denise Bonilla, Marieta Braks, Lawrence Bronson, Joseph Burns, Richard Davis, Tina Fieszli, Tim Howard, Laura Krueger, Mark Novak, and James Tucker of the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) Vector-Borne Disease Section for expert assistance in field activities; Merry Schrumpf for technical assistance in the laboratory; and Mark Novak for valuable comments on the manuscript. This work was supported, in part, by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH) (T.G.S.), a cost-share agreement between the CDPH and the USFS, and a memorandum of understanding between CDPH and the NPS Office of Public Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no competing commercial or financial interests.

References

- Boyer KM. Munford RS. Maupin GO. Pattison CP, et al. Tick-borne relapsing fever: An interstate outbreak originating at Grand Canyon National Park. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;105:469–479. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorfer W. Mavros AJ. Susceptibility of various species of rodents to the relapsing fever spirochete, Borrelia hermsii. Infect Immun. 1970;2:256–259. doi: 10.1128/iai.2.3.256-259.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Fish and Game. Complete list of amphibian, reptile, bird and mammal species in California. 2008. www.dfg.ca.gov/biogeodata/cwhr/pdfs/species_list.pdf/ [Nov 22;2012 ]. p. 25.www.dfg.ca.gov/biogeodata/cwhr/pdfs/species_list.pdf/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Common source oubreak of relapsing fever —California. MMWR. 1990;39:579–586. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tickborne relapsing fever outbreak after a family gathering—New Mexico, August 2002. MMWR. 2003;52:809–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in persons with tickborne relapsing fever—three states, 2004–2005. MMWR. 2007;56:1073–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary M. Theis J. Identification of a novel strain of Borrelia hermsii in a previously undescribed northern California focus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:883–887. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin MS. Anderson DE., Jr. Schwan TG. Shoemaker PC, et al. Tick-borne relapsing fever in the northwestern United States and southwestern Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:122–131. doi: 10.1086/516273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin MS. Schwan TG. Anderson DE., Jr. Borshardt SM. Tick-borne relapsing fever. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2008;22:449–468. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edell TA. Emerson JK. Maupin GO. Barnes AM, et al. Tick-borne relapsing fever in Colorado. J Am Med Assoc. 1979;241:2279–2282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz CL. Bronson LR. Smith CR. Schriefer ME, et al. Isolation and characterization of Borrelia hermsii associated with two foci of tick-borne relapsing fever in California. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1123–1128. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1123-1128.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs PC. Oyama AA. Neonatal relapsing fever due to transplacental transmission of Borrelia. J Am Med Assoc. 1969;208:690–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JR. Fritz CL. Novak MG. Occupational risk of exposure to rodent-borne hantavirus at US Forest Service facilities in California. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:352–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter GS. Beck MD. Stevens IM. Relapsing fever in California. Am J Publ Health. 1932;22:1136–1140. doi: 10.2105/ajph.22.11.1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwan TG. Schrumpf ME. Hinnebusch BJ. Anderson DE, Jr., et al. GlpQ: An antigen for serological discrimination between relapsing fever and Lyme borreliosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2483–2492. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2483-2492.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwan TG. Policastro PF. Miller Z. Thompson RL, et al. Tick-borne relapsing fever caused by Borrelia hermsii, Montana. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1151–1154. doi: 10.3201/eid0909.030280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwan TG. Raffel SJ. Schrumpf ME. Webster LS, et al. Tick-borne relapsing fever and Borrelia hermsii, Los Angeles County, California, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1026–1031. doi: 10.3201/eid1507.090223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern PM., Jr Sanford JP. Relapsing fever: A clinical and microbiological review. Medicine (Baltimore) 1969;48:129–149. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RS. Burgdorfer W. Russell R. Francis BJ. Outbreak of tick-borne relapsing fever in Spokane County, Washington. J Am Med Assoc. 1969;210:1045–1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevejo RT. Schriefer ME. Gage KL. Safranak TJ, et al. An interstate outbreak of tick-borne relapsing fever among vacationers at a Rocky Mountain cabin. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:743–747. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]