Abstract

Both dose-dense and dose-escalation chemotherapy are administered in clinic. By approximately imitating the schedules of dose-dense and dose-escalation administration with paclitaxel, two novel multidrug resistant (MDR) cell lines Bads-200 and Bats-72 were successfully developed from drug-sensitive breast cancer cell line BCap37, respectively. Different from Bads-200, Bats-72 exhibited stable MDR and significantly enhanced migratory and invasive properties, indicating that they represented two different MDR phenotypes. Our results showed that distinct phenotypes of MDR could be induced by altered administration strategies with a same drug. Administrating paclitaxel in conventional dose-escalation schedule might induce recrudescent tumor cells with stable MDR and increased metastatic capacity.

Keywords: Dose-dense chemotherapy, Dose-escalation chemotherapy, Multidrug resistance, Migration, Invasion

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death among females, accounting for 23% of the total new cancer cases and 14% of the cancer deaths in 2008[1]. Although various treatments are currently available, chemotherapy remains one of the most important therapeutic strategies for breast cancer[2; 3; 4]. Anthracycline-based regimens and taxanes (paclitaxel and docetaxel) are currently considered as standard first-line chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer (MBC)[3]. In clinic, most chemotherapeutic treatments are administered over a period of several hours at cycles of every 21–28 days[5]. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved dosing schedules for taxanes in MBC are 60–100 mg/m2 for docetaxel (1-hour i.v.) and 175 mg/m2 for paclitaxel (3-hour i.v.) every 3 weeks, respectively[6].

However, recent novel schedules of chemotherapy administration appear to incrementally improve therapeutic outcome[7]. The concept of dose-dense chemotherapy, administering the drugs with a shortened intertreatment interval, is based on the observation that a given dose of chemotherapy always kills a certain fraction of exponentially growing cancer cells[8]. By administering lower doses more frequently, toxicity to normal tissues may be decreased without compromising the drug's antitumor efficacy.[6] Thus, it is believed that more frequent administrations of cytotoxic agents would be more effective in minimizing residual tumor burden compared to conventional dose-escalation chemotherapy[7; 9; 10]. Numerous mono and combination chemotherapy trials suggested that weekly administration of paclitaxel has a better therapeutic index than the standard every 3-week regimen and is not associated with increased side effects[9; 11; 12; 13]. These results are very encouraging for the incorporation of dose-dense chemotherapy in every day practice for breast cancer.

Although anticancer therapies with different schedules of administration will alter tumor growth, the effect is usually not long lasting. Due to multiple factors including drug resistance, tumor recurrences frequently occur months to years after an effective response to initial chemotherapy[14]. Previous studies reported that around 40% of breast cancer patients suffer a recurrence[15; 16]. The recurrent tumor cells are usually more aggressive, with different phenotypes of drug resistance as well as formidable migration and invasion. The aim of the present study is to determine whether different administration methods with the same anticancer drug could affect the properties of recrudescent tumor cells.

In this study, two newly MDR cell lines, Bads-200 and Bats-72, were developed from chemo-sensitive human breast cancer cell line BCap37 by using different screening strategies. Bads-200 was induced by conventional continuous exposure to paclitaxel with dose-stepwise increments, while Bats-72 was developed by an improved method based on pulsed exposure to paclitaxel with time-stepwise increments. Through a series of comparative studies, we found that Bads-200 and Bats-72 represented two different MDR phenotypes, indicating that different administration strategies with the same anticancer drug could induce distinct phenotypes of MDR in breast cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell lines and mice

Human breast cancer cell lines BCap37, Bads-200 and Bats72, were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Female aged 5 to 6 weeks of athymic nude (nu/nu) mice were purchased from Shanghai SLAC animal facility. All animal care and experiments were conducted according to Zhejiang University Animal Care Committee guidelines.

2.2. Examination of morphology and cell growth rate in vitro

BCap37, Bats-72 and Bads-200 cells were sub-cultured into 35-mm dishes for 48 h. Giemsa staining was carried out by a commercial kit (Jiangcheng Biotech, Nanjing, China). Stained cells were observed and photographed with a bright field microscope. To determine the cell growth rate in vitro, BCap37, Bats-72 and Bads-200 cells were plated into 6-well tissue culture plates at a density of 4 × 104 cells/well. Two cell counts for each cell line were made every 24 h for 10 days. The obtained data were subjected to linear regression analysis, in which the population doubling time (Td) was calculated based on the formula Td= ln2/slope.

2.3. 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay

As described previously[17], cells were harvested and resuspended to a final concentration of 1 × 104 cells/ml. Aliquots of the cell suspension were evenly distributed into 96-well tissue culture plates. After one night of incubation, the designated columns were treated with drug regimes. Four hours prior to the end of time point, MTT solution was added. The medium containing MTT was replaced with 150 μL of DMSO in each well to dissolve the formazan crystals after 4 h-incubation. The absorbance in individual wells was determined at 560 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Sunnyvale, CA).

2.4. Examination of cell growth rate and drug resistance in vivo

To develop the human breast xenografts, in vitro growing BCap37, Bads-200 and Bats-72 cells (1 × 106 cells in 0.2 mL PBS) were implanted into the right flanks of the homozygous nude athymic mice (female, 5-6-weeks old). When tumors reached a mean diameter of 0.4–0.6 cm, each type of xenografts were randomly divided into 3 groups and treated with (i) Vehicle; (ii) fulvestrant (2 mg per mouse, i.m.), (iii) paclitaxel (20 mg/kg, i.v.). The same treatment regimens were repeated every 3 days for total of 6 cycles. Two perpendicular diameters (width and length) of the tumors and body weight of mice were measured every 3 days until the animals were killed. The curve of tumor growth was drawn based on tumor volume and corresponding time (days) after treatment. When the animals were terminated, the tumor tissues were removed and weighted. The inhibition rate of tumor growth (IR) was calculated according to the following formula: IR = 100% × (mean tumor weight of control group – mean tumor weight of experimental group)/mean tumor weight of control group [18]. Data are representative of 2 separate experiments.

2.5. Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-PCR)

Total RNAs from BCap37, Bats-72 and Bads-200 cells were isolated with TRIzol, purified and dissolved in RNase-free water. RT-PCR was performed to determine the expression of ABCB1, ABCC1 and ABCG2 in BCap37, Bats-72 and Bads-200 respectively. The primers were designed as follows: ABCB1, forward: 5′- ATGCCTTCATCGAGTCACTGC -3′ and reverse: 5′- ACGAGCTATGGCAATGCGTT -3′; ABCC1, forward: 5′- AGCGCTTCCTTCCTGTCGA -3′ and reverse: 5′- TGTTCCGACGTGTCCTCCTT -3′; forward: 5′- AGGATTGAAGCCAAAGGCAGA -3′ and 5′- GACCTGCTGCTATGGCCAGT-3′; 18S rRNA, forward: 5′- CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA -3′ and reverse: 5′- GCTGGAATTACCGCGGCT-3′; 18S rRNA served as an internal control. All assays were set up for a relative quantitative method, in which mean Ct values from BCap37 samples were used as calibrators for data analysis for both Bats-72 and Bads-200 samples. The relative fold changes (FC) of gene expression were calculated by using the standard 2−ΔΔct method.

2.6. Western blotting

Cellular proteins were isolated with a protein extraction buffer (Beyotime, Haimen, China). Equal amounts (40 μg/lane) of proteins were fractionated on 6–10% SDS–PAGE gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were incubated with anti-MDR, anti-MRP1, anti-BCRP primary antibodies (Santa Cruz, CA), respectively. After washing with PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20, the membranes were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse secondary antibodies followed by enhanced chemiluminescent staining using the ECL system. β-actin was used for normalization of protein loading [19].

2.7. Rhodamine 123 efflux assay

Cells were incubated by incubation medium (Hanks' balanced salt solution supplemented with 10% FBS) with or without verapamil. Followed by incubation for 30 min, Rhodamine 123 was added into the incubation medium (10 μg/mL). The cells were then incubated for additional 1 h. After washed with ice-cold PBS, the cells were trypsinized and resuspended in 500 μL PBS. Intracellular Rhodamine 123 fluorescence intensity was determined with Coulter Epics V instrument (Beckman Coulter,, CA).

2.8. In vitro migration and invasion assay

Migration assays were performed in a 24-well Transwell chamber (Corning, MA). Briefly, 5 × 104cells were seeded to upper chamber in 200 μL of serum-free medium. The lower parts of the chambers were filled with 600 μL of RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS. After incubation for 12 h, the migration cells were then fixed, stained and enumerated. The same procedures were followed for the invasion assay except each Transwell chamber was coated with 30 μg Matrigel and incubation for 24 h.

2.9. In vivo tumor metastasis assay

According to method described previously[20], a total of 0.5 million cells were injected into each nude mouse (female, 5 weeks old) through tail veins. After 4 weeks, the animals were killed, and lungs were harvested and fixed in 10% neutral formalin, embedded in paraffin. Slides were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) followed by examination and photography under microscopy.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of three independent experiments. Two-sided Student's t test was used to determine the statistical difference between various experimental and control groups. Differences were considered statistically significant at a level of P<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Establishment and morphological characterizations of drug resistant cell lines

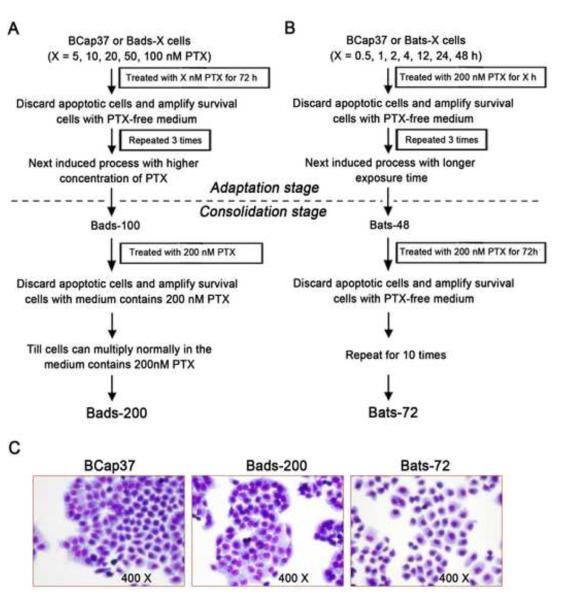

BCap37 is an ER-negative and Her2-positive human breast cancer cell line (Supplementary Fig. S1). Bads-200 cells were selected based on continuous exposure to paclitaxel using a dose-stepwise incremental strategy from BCap37 (Fig. 1A). In the adaptation stage, BCap37 cells were exposed to paclitaxel for 72 h in stepwise increments of concentrations ranging from 5 nM to 100 nM (5, 10, 20, 50, 100 nM). Following each dose-induced step, surviving cells were amplified in paclitaxel-free medium. After repeating 3 times (for each dose), cells were exposed to the next higher concentration of paclitaxel. In the consolidation stage, previously selected cells were continuously cultured in medium containing 200 nM paclitaxel, until they multiplied normally in medium containing 200 nM paclitaxel. The resulting resistant cell line (Bads-200) was maintained in medium containing 200 nM paclitaxel.

Fig. 1. Establishment and morphological characterization of Bads-200 and Bats-72.

Bads-200 and Bats-72, from human breast cancer cell line BCap37 by different screening strategies. A, Bads-200 was induced by conventional continuous exposure to paclitaxel with dose-stepwise increment. B, Bats-72 was selected by an improved method based on pulsed exposure to paclitaxel with time-stepwise increment; C, morphological characteristics were determined by inverted microscopic examination after Giemsa staining. PTX, paclitaxel.

Bats-72 cells were produced based on a strategy of pulsed exposure to paclitaxel with time-stepwise increments (Fig. 1B). Briefly, BCap37 cells were exposed to 200 nM paclitaxel in time increments ranging from 0.5 h to 48 h(0.5, 1, 2, 4, 12, 24, 48 h) in the adaptation stage. The surviving cells were amplified in paclitaxel-free medium. Each pulse treatment was repeated 3 times, followed by exposure to the next longer time-course. In the consolidation stage, previously selected cells were exposed to ten pulses of treatment with 200 nM paclitaxel for 72 h. The resulting cell line was named Bats-72 and was maintained in paclitaxel-free medium. As shown in Fig. 1C, Bads-200 cells were morphologically similar to BCap37, but their growth was more cohesive with clearly demarcated and tight colony edges. Compared to BCap37 and Bats-200, Bats-72 cells were relatively larger with a reduced nucleus-to-cell ratio.

3.2. Both Bads-200 and Bats-72 were more aggressive in vivo

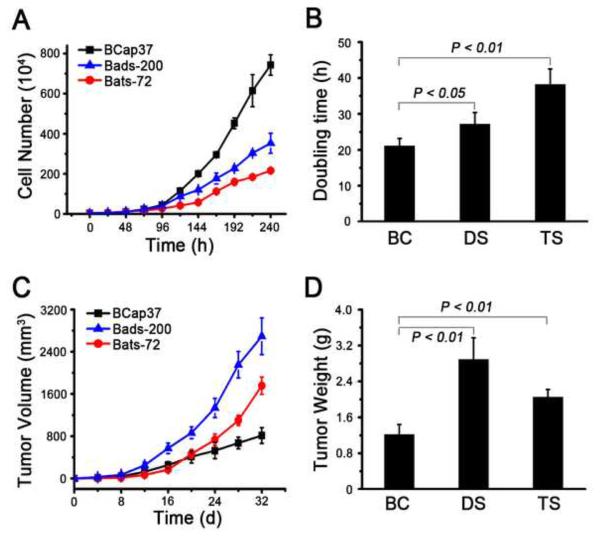

In vitro growth assays showed that both resistant derivatives displayed significantly reduced proliferation rates compared to parental BCap37 cells (Fig. 2A). The doubling time for BCap37, Bads-200 and Bats-72 cell lines were 21.1±1.9, 26.2±3.2 and 39.4±4.1 h, respectively (Fig. 2B).

Fig.2. Bads-200 and Bats-72 were more aggressive in vivo.

A, in vitro growth curves of BCap37, Bats-72 and Bads-200 cell lines, B, the doubling time for BCap37, Bads-200 and Bats-72 cell lines. C, tumor volume curves of nude mice bearing BCap37, Bads-200 or Bats-72. P values were determined by one-way ANOVA test; P < 0.01. D, tumor weight at the end of experiments for each group of mice bearing BCap37, Bads-200 or Bats-72. Data presented in the graphs are mean ± SE of three independent experiments. BC, BCap37; DS, Bads-200; TS, Bats-72.

To determine the proliferation kinetics of BCap37, Bads-200 and Bats-72 cells in vivo, we established tumor xenograft models through injection of 2 × 106 cells into the right flanks of nude mice and measured tumor volumes every 4 days. When the animals were terminated in 32 days, mean tumor volumes of BCap37, Bads-200 and Bats-72 were 814±149, 2693±348 and 1756±163 mm3, respectively (Fig. 2C, n=6). Mean tumor weights of BCap37, Bads-200 and Bats-72 were significantly different at approximately 1.22±0.22, 2.89±0.48 and 2.05±0.17 g, respectively (Fig. 2D). These results showed that, in contrast with the in vitro data, drug resistant cell lines Bads-200 and Bats-72 exhibited more aggressive proliferation than BCap37 in vivo.

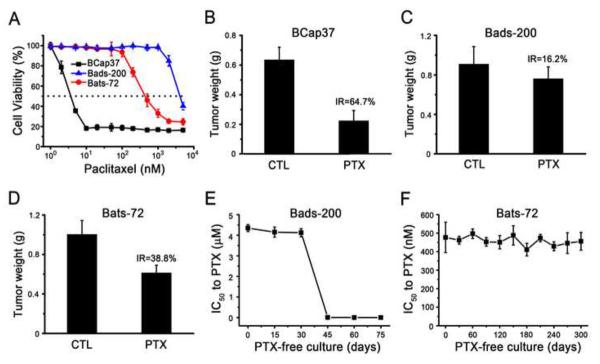

3.3. Bads-200 and Bats-72 exhibited different phenotypes of MDR

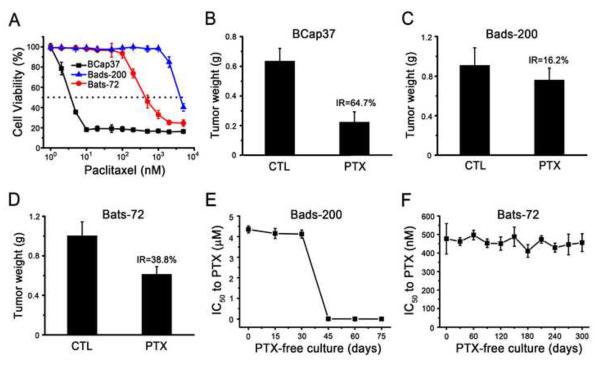

Because Bads-200 and Bats-72 were selected by paclitaxel, we first examined their sensitivities to paclitaxel using MTT assays. As shown in Fig. 3A and table 1, the IC50 values of 72 h paclitaxel exposure for BCap37, Bads-200 and Bats-72 were 4±1.2, 4,550±340 and 454±65 nM, respectively. The IC50 values indicated that Bads-200 and Bats-72 were about 1140-fold and 113-fold more resistant to paclitaxel than parental BCap37, respectively. Flow cytometric analyses also indicated that both Bads-200 and Bats-72 were much more resistant to paclitaxel-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. S2 and S3). Subsequently, we also demonstrated that Bads-200 and Bats-72 were more resistant to paclitaxel in vivo (Supplementary Fig. S4). Compared to control group (vehicle, i.v.), the inhibitory rates of paclitaxel (20mg/kg, i.v.) on BCap37, Bads-200 and Bats-72 tumors were 64.7, 16.2 and 38.8%, respectively (Fig. 3B, 3C and 3D). Corresponding tissue sections were stained with H&E or for the proliferation marker Ki-67. Compared to BCap37 cells, fewer Bads-200 and Bats-72 cells exhibited vacuolization and apoptotic features (Supplementary Fig. S5), but more Bads-200 and Bats-72 cells were Ki-67 positive (Supplementary Fig. S6). Obviously, Bads-200 exhibited the stronger resistance to paclitaxel in vivo than Bats-72.

Fig.3. Bads-200 and Bats-72 presented different resistant phenotypes.

A, Bads-20 and Bats-72 were significantly resistant to the cell-killing activity of paclitaxel in vitro. Cells were treated with paclitaxel for 72h; B, C, D, Bads-20 and Bats-72 were significantly resistant to t paclitaxel in vivo. Nude mice bearing BCap37, Bads-200 or Bats-72 tumors were treated with or without paclitaxel (20 mg/kg, i.v., q3d × 6). The tumor volume and tumor weight were measured and calculated as described in Materials and Methods. E, stability of resistance phenotype in Bads-200; F, stability of resistance phenotype in Bats-72. Both Bats-72 and Bads-200 were cultured with paclitaxel-free medium. The IC50 values of 72 h paclitaxel exposure were evaluated by MTT assays every 30 days for Bats-72 and every 15 days for Bads-200. Data presented in the graphs are mean ± SE of three independent experiments. BC, BCap37; DS, Bads-200; TS, Bats-72; CTL, control; PTX, paclitaxel; IR, Inhibition rate.

Table 1.

Drug sensitivity of BCap37, Bads-200 and Bats-72

| Drug | BCap37 |

Bads-200 |

Bats-72 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 * (nM) | IC50 (nM) | RI** | IC50 (nM) | RI | |

| Paclitaxel | 4 ± 1.2 | 4550 ± 340 | 1138 | 454 ± 65 | 113.5 |

| Docetaxel | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 1680 ± 80 | 622.2 | 248 ± 38 | 91.9 |

| Vinorelbine | 20 ± 3.4 | 1850 ± 160 | 92.5 | 1040 ± 180 | 52 |

| Doxorubicin | 270 ± 26 | 9950 ± 650 | 36.9 | 5600 ± 240 | 20.7 |

| Etoposide | 12300 ± 800 | 79000 ± 5200 | 6.4 | 59100 ± 3300 | 4.8 |

| Gemcitabine | 418 ± 36 | 482 ± 63 | 1.2 | 1400 ± 90 | 3.4 |

| Methotrexate | 18.6 ± 3.9 | 19.6 ± 7.4 | 1.1 | 39.5 ± 5.8 | 2.12 |

| 5-flourouracil | 15200 ± 1200 | 22400 ± 1800 | 1.5 | 25800 ± 2300 | 1.7 |

| Cisplatin | 1550 ± 240 | 1220 ± 210 | 0.79 | 1500 ± 170 | 0.97 |

The IC50 values were defined as the concentration of cells inhibiting growth at 50%.

Drug resistance index (RI) was determined by deviding IC50 values of Bads-200 or Bats-72 by that of BCap37 cells.

To further characterize the drug resistant profile of Bats-72 and Bads-200, their in vitro sensitivities to several different chemotherapeutic agents were assessed using MTT assays. The results were summarized in Table 1. In general, both Bads-200 and Bats-72 exhibited significantly higher resistance than BCap37 to docetaxel, vinorelbine, doxorubicin and etoposide. Especially, Bats-72 showed additional resistance to methotrexate (2.12 fold) and gemcitabine (3.4 fold). These data indicated that both Bads-200 and Bats-72 were MDR cell lines, but with different resistance profiles.

Moreover, Bads-200 and Bats-72 cell lines were continuously cultured in paclitaxel-free medium to observe the stability of their resistant phenotypes. As presented in Fig. 3E, when Bads-200 cells were cultured in paclitaxel-free medium up to approximate 15 passages (around 30 – 45 days), the IC50 values of 72 h paclitaxel exposure in Bads-200 cells decreased from 4450 nM to 3.6 nM. It indicated that the resistance of Bads-200 cell line to paclitaxel appeared to be transient, lasting for approximately one month before reverting. In contrast, Bats-72 cells maintained the resistant phenotype, with stable IC50 values for paclitaxel over 10-months of continuous culture in drug-free medium (Fig. 3F). These findings suggested that Bads-200 and Bats-72 might represent two distinct MDR phenotypes.

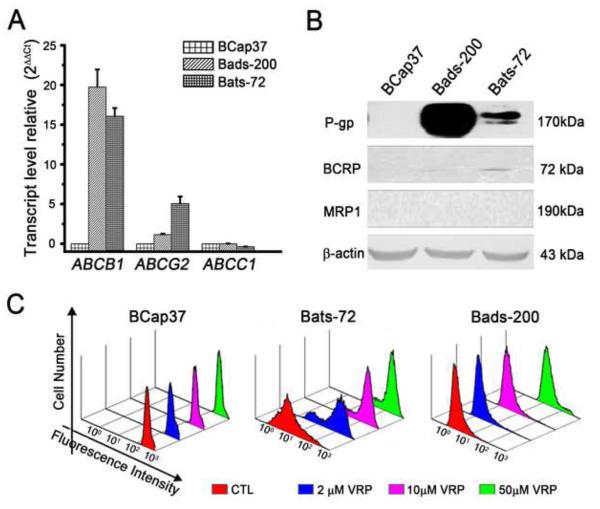

3.4. Expression of ABC transporters and chemo-sensitization by MDR modulators in Bads-200 and Bats-72

A well-known mechanism of MDR involves the increased expression of members of the ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. Specific ABC transporters, most notably P-glycoprotein (P-gp/ABCB1), multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1/ABCC1) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2), can efflux a wide range of chemotherapeutic agents and result in drug resistance [21]. Compared to BCap37 cells, over-expression of ABCB1 and corresponding P-gp protein were observed in both Bads-200 and Bats-72 cells. In addition, up-regulation of ABCG2 mRNA and corresponding BCRP protein were only detected in Bats-72 (Fig. 4A and 4B). Furthermore, Rhodamine 123 was used as a molecular probe in drug efflux assay, to investigate whether intracellular drug accumulation was significantly decreased in Bads-200 and Bats-72 cells. No significant change in Rhodamine 123 retention was observed in BCap37 cells with or without verapamil co-treatment. Conversely, co-treatment of 2, 10 and 50μM verapamil significantly inhibited Rhodamine 123 efflux in both Bads-200 and Bats-72 cell lines (Fig. 4C). To further investigate whether MDR of Bad-200 and Bats-72 could be regulated or reversed by MDR modulators, tumor cells were treated with verapamil or tetrandrine, two known MDR modulators [22; 23; 24], prior to treatment of paclitaxel. The results showed that co-treatment of verapamil (2 and 10 μM) or tetrandrine (0.1 and 0.5 μM) with paclitaxel significantly sensitized Bads-200 and Bats-72 to paclitaxel in a dose dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Fig.4. Expression of ABC transporters plays an important role in mediating the MDR of both Bads-200 and Bats-72.

A, quantitative RT-PCR was performed to determine the expression of ABCB1, ABCC1 and ABCG2. Each sample was measured in triplicate, and gene expression levels are shown as the mean normalized to the expression of 18S rRNA. B, detect the expression of P-gp, BCRP and MRP1 in BCap37, Bats-72 and Bads-200 cells. Equal amounts (40 μg/lane) of proteins were analyzed. C, as described in Materials and Methods, Bats-72 and Bads-200 cells were treated with combinations of 10 μg/ml Rhodamine 123 and 0, 2, 10, 50 μM verapamil. The intracellular fluorescence intensity of Rhodamine 123 was determined with Coulter Epics V instrument.

3.5. Bats-72, but not Bads-200, exhibited enhanced migration and invasion

Metastasis is typically accompanied by increased aggressiveness in tumor cells [25]. Cell migration and invasion is a significant aspect of tumor metastasis [26]. Using a Transwell chamber, we analyzed the migratory activity of BCap37, Bads-200 and Bats-72 cells. Compared with parental BCap37 cells, the migratory ability of Bads-200 cells were essentially unchanged, but Bats-72 cells showed a significant increase in migration (Fig. 5A). The migratory activity of Bats-72 was increased by approximately 3.5-fold (Fig. 5B). Similar results were also observed in Matrigel invasion assays (Fig. 5C). Bats-72, but not Bads-200, showed approximate 10-fold increase of invasion over those in parental BCap37 cells (Fig. 5D). These data showed that Bats-72 but not Bads-200 exhibited significantly enhanced migratory and invasive properties in vitro. Furthermore, to examine metastatic capacity in vivo, BCap37, Bads-200 or Bats-72 cells were injected into nude mice through the tail veins. After 4 weeks, the lung metastases were measured by H&E. As shown in Figure 5E, metastatic tumor cells were only detected in mice bearing Bats-72 cells, suggesting that Bats-72, but not Bads-200 exhibited enhanced ability of metastasis.

Fig.5. Bats-72 showed significantly enhanced migratory and invasive properties.

A, migration of BCap37, Bads-200 and Bats-72 were analyzed by transwell assay. After 12 h incubation, the number of cells on the lower surface of the filters was quantified under a microscope B, histogram showed the number of migrant cells per field. C, invasion of BCap37, Bads-200 and Bats-72 were analyzed by transwell assay. After 24 h incubation, the number of cells on the lower surface of the filters was quantified under a microscope. D, histogram showed the number of invasive cells per field. E, histopathology analyses of lung tissues from the mice bearing BCap37, Bads-200 and Bats-72, respectively. Data presented in the graphs are mean ± SE or representatives of three independent experiments. BC, BCap37; DS, Bads-200; TS, Bats-72.

4. Discussion

In clinical practice of cancer therapy, many patients show initial sensitivity to anticancer drugs, but the therapeutic effects of drugs are usually transient. Tumor recurrences probably occur months to years after an original response to chemotherapy[14]. Currently, tumor recurrence after chemotherapy, a major obstacle to successful tumor treatment[27], is considered as a multifactorial phenomenon[28; 29]. Drug resistance is believed to be the most common cause for tumor recurrence[30; 31]. Drug resistant cell line derived from chemo-sensitive tumor cell line is one of the principal tools to investigate drug resistance and tumor recurrence after chemotherapy[5]. There are two general methods for establishing chemotherapy resistant cancer cell lines, continuous low-concentration treatment and pulsatile treatment, with the first method most commonly used by researchers[32; 33; 34; 35]. Ultimately, knowledge obtained from MDR cell models in laboratory must be associated with the resistance to chemotherapy in actual cancer patients[5]. Therefore, the method chosen for establishment of the drug resistant cell lines should be related to the clinical setting.

In clinic, most conventional dose-escalation chemotherapy regimens are administered at cycles of every 21–28 days[5]. For example, a 3 weekly schedule is recommended for paclitaxel administration in MBC. Thus, the pulsatile treatment potentially offers a more suitable approximation of this cyclic therapy protocol. In addition, the chemotherapeutic drugs usually have different half-lives of durations and active times in patient's body, along with different rates for metabolism and clearance from the body[36]. In this respect, we offered an improved pulsatile treatment regime, pulsed exposure with time-stepwise increments, by which a newly MDR breast cancer cell line Bats-72 was developed. The exposure time can be increased to match the specific drug's active time in clinic.

Based on the concept of dose-dense chemotherapy, paclitaxel administered on a weekly schedule has been studied extensively both as a single agent and in combination chemotherapy. Weekly, rather than the standard every-3-weeks, lower dosing of paclitaxel provides an efficacious method to deliver drug while maintaining a favorable toxicity profile. Various studies support weekly taxane dosing as an active regimen in MBC[6; 9; 11; 12; 13]. Importantly, this regimen is associated with a low incidence of severe hematologic toxicities and acute non-hematologic toxicities. These results are very encouraging for the incorporation of dose-dense chemotherapy in every day practice for MBC. Thus, continuous exposure with dose-stepwise increments, by which another newly MDR breast cancer cell line Bads-200 was developed, potentially offers an approximation of dose-dense chemotherapy.

Both Bads-200 and Bats-72 were derived from BCap37 by the same agent, paclitaxel, but with different administration strategies. Compared to parental BCap37 cells, both Bads-200 and Bats-72 were cross-resistant to paclitaxel, docetaxel, vinorelbine, doxorubicin, etopside, and sensitive to cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil. Moreover, Bats-72 showed additional resistance to methotrexate and gemcitabine. ABCB1 and P-gp were dramatically up-regulated in both Bads-200 and Bats-72 cells, whereas up-regulation of ABCG2 and BCRP were only detected in Bats-72. Interestingly, the resistant phenotype of Bads-200 could be reversed when the cells were maintained or cultured in a drug-free medium, whereas Bats-72 displayed stable resistant property under continuous drug-free culture. Also, different from Bads-200, Bats-72 exhibited significantly enhanced migratory and invasive properties. Obviously, Bads-200 and Bats-72 were distinct from each other and represented two different MDR phenotypes. These findings indicated that different administration strategies with a single drug such as paclitaxel could induce distinct phenotypes of MDR.

Based on the results from this study, different MDR subclones like Bads-200 and Bats-72 could be derived from the same cell population using same selecting agent but different selection strategies, suggesting that different treatments with the same drug in clinic might induce various types of MDR. Compared with Bads-200, Bats-72 exhibited stable MDR and significantly enhanced migratory and invasive properties. Thus, administrating paclitaxel in conventional dose-escalation schedule might induce recrudescent tumor cells with stable MDR and increased metastatic capacity. Further studies may focus on improving drug treatment to match the clinical setting. Drug resistant cell lines developed in experimental animals would be also valuable to understand the influence of administration strategies on recurrent tumor cells.

In summary, by using different screening strategies, we established two novel MDR cell lines, Bads-200 and Bats-72, from chemo-sensitive human breast cancer cell line BCap37. Although Bads-200 and Bats-72 shared the same origin, they exhibited distinguishable characteristics and represented two different MDR phenotypes. These findings indicated that distinct phenotypes of MDR could be induced by altered administration strategies with the same anticancer drug. In addition, BCap37, Bads-200 and Bats-72 may serve as a valuable cell model system for gaining molecular insights into breast cancer MDR, metastasis and tumor recurrence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Robert Gemmill and Dr. Han Ning for their critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported in part by Grants NNSF-81071880, NNSF-30973456 and NIH CA92880 (to Fan, W).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- [1].Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Johnston SR. The role of chemotherapy and targeted agents in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2011;47(Suppl 3):S38–47. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(11)70145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rivera E, Gomez H. Chemotherapy resistance in metastatic breast cancer: the evolving role of ixabepilone. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(Suppl 2):S2. doi: 10.1186/bcr2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Murphy CG, Khasraw M, Seidman AD. Holding back the sea: the role for maintenance chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer. Breast cancer Res. Treat. 2010;122:177–179. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0925-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Watson MB, Lind MJ, Cawkwell L. Establishment of in-vitro models of chemotherapy resistance. Anticancer Drugs. 2007;18:749–754. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3280a02f43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Eniu A, Palmieri FM, Perez EA. Weekly administration of docetaxel and paclitaxel in metastatic or advanced breast cancer. Oncologist. 2005;10:665–685. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-9-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kaklamani VG, Gradishar WJ. Adjuvant therapy of breast cancer. Cancer Invest. 2005;23:548–560. doi: 10.1080/07357900500202937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Skipper HE. Laboratory models: some historical perspective. Cancer Treat. Rep. 1986;70:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Citron ML, Berry DA, Cirrincione C, Hudis C, Winer EP, Gradishar WJ, Davidson NE, Martino S, Livingston R, Ingle JN, Perez EA, Carpenter J, Hurd D, Holland JF, Smith BL, Sartor CI, Leung EH, Abrams J, Schilsky RL, Muss HB, Norton L. Randomized trial of dose-dense versus conventionally scheduled and sequential versus concurrent combination chemotherapy as postoperative adjuvant treatment of node-positive primary breast cancer: first report of Intergroup Trial C9741/Cancer and Leukemia Group B Trial 9741. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:1431–1439. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Katsumata N, Yasuda M, Takahashi F, Isonishi S, Jobo T, Aoki D, Tsuda H, Sugiyama T, Kodama S, Kimura E, Ochiai K, Noda K. Dose-dense paclitaxel once a week in combination with carboplatin every 3 weeks for advanced ovarian cancer: a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1331–1338. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].John M, Hinke A, Stauch M, Wolf H, Mohr B, Hindenburg HJ, Papke J, Schlosser J. Weekly paclitaxel plus trastuzumab in metastatic breast cancer pretreated with anthracyclines--a phase II multipractice study. BMC cancer. 2012;12:165. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Seidman AD, Hudis CA, Albanell J, Tong W, Tepler I, Currie V, Moynahan ME, Theodoulou M, Gollub M, Baselga J, Norton L. Dose-dense therapy with weekly 1-hour paclitaxel infusions in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998;16:3353–3361. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.10.3353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Perez EA, Vogel CL, Irwin DH, Kirshner JJ, Patel R. Multicenter phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel in women with metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001;19:4216–4223. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.22.4216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dean M, Fojo T, Bates S. Tumour stem cells and drug resistance. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:275–284. doi: 10.1038/nrc1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Al-Ejeh F, Smart CE, Morrison BJ, Chenevix-Trench G, Lopez JA, Lakhani SR, Brown MP, Khanna KK. Breast cancer stem cells: treatment resistance and therapeutic opportunities. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:650–658. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gerber B, Freund M, Reimer T. Recurrent breast cancer: treatment strategies for maintaining and prolonging good quality of life. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2010;107:85–91. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sui M, Huang Y, Park BH, Davidson NE, Fan W. Estrogen receptor alpha mediates breast cancer cell resistance to paclitaxel through inhibition of apoptotic cell death. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5337–5344. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sui M, Chen F, Chen Z, Fan W. Glucocorticoids interfere with therapeutic efficacy of paclitaxel against human breast and ovarian xenograft tumors. Int. J. Cancer. 2006;119:712–717. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sui M, Jiang D, Hinsch C, Fan W. Fulvestrant (ICI 182,780) sensitizes breast cancer cells expressing estrogen receptor alpha to vinblastine and vinorelbine. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010;121:335–345. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0472-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zhu S, Wu H, Wu F, Nie D, Sheng S, Mo YY. MicroRNA-21 targets tumor suppressor genes in invasion and metastasis. Cell Res. 2008;18:350–359. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Eckford PD, Sharom FJ. ABC efflux pump-based resistance to chemotherapy drugs. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:2989–3011. doi: 10.1021/cr9000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhu X, Sui M, Fan W. In vitro and in vivo characterizations of tetrandrine on the reversal of P-glycoprotein-mediated drug resistance to paclitaxel. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:1953–1962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gottesman MM, Fojo T, Bates SE. Multidrug resistance in cancer: role of ATP-dependent transporters. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:48–58. doi: 10.1038/nrc706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Grossi A, Biscardi M. Reversal of MDR by verapamil analogues. Hematology. 2004;9:47–56. doi: 10.1080/10245330310001639009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].King CE, Cuatrecasas M, Castells A, Sepulveda AR, Lee JS, Rustgi AK. LIN28B promotes colon cancer progression and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4260–4268. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Khan N, Mukhtar H. Cancer and metastasis: prevention and treatment by green tea. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:435–445. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9236-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Achuthan S, Santhoshkumar TR, Prabhakar J, Nair SA, Pillai MR. Drug-induced senescence generates chemoresistant stemlike cells with low reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:37813–37829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.200675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Konstantinidou AE, Korkolopoulou P, Patsouris E. Apoptotic markers for tumor recurrence: a minireview. Apoptosis. 2002;7:461–470. doi: 10.1023/a:1020091226673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Song J, Shih Ie M, Salani R, Chan DW, Zhang Z. Annexin XI is associated with cisplatin resistance and related to tumor recurrence in ovarian cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13:6842–6849. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wang Z, Li Y, Ahmad A, Azmi AS, Kong D, Banerjee S, Sarkar FH. Targeting miRNAs involved in cancer stem cell and EMT regulation: An emerging concept in overcoming drug resistance. Drug Resist. Updat. 2010;13:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Di Nicolantonio F, Mercer SJ, Knight LA, Gabriel FG, Whitehouse PA, Sharma S, Fernando A, Glaysher S, Di Palma S, Johnson P, Somers SS, Toh S, Higgins B, Lamont A, Gulliford T, Hurren J, Yiangou C, Cree IA. Cancer cell adaptation to chemotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2005;5:78. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Yu DS, Ma CP, Chang SY. Establishment and characterization of renal cell carcinoma cell lines with multidrug resistance. Urol. Res. 2000;28:86–92. doi: 10.1007/s002400050143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Benavente S, Huang S, Armstrong EA, Chi A, Hsu KT, Wheeler DL, Harari PM. Establishment and characterization of a model of acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor targeting agents in human cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:1585–1592. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Smith V, Rowlands MG, Barrie E, Workman P, Kelland LR. Establishment and characterization of acquired resistance to the farnesyl protein transferase inhibitor R115777 in a human colon cancer cell line. Clin. Cancer Res. 2002;8:2002–2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Takemura Y, Kobayashi H, Gibson W, Kimbell R, Miyachi H, Jackman AL. The influence of drug-exposure conditions on the development of resistance to methotrexate or ZD1694 in cultured human leukaemia cells. Int. J. Cancer. 1996;66:29–36. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960328)66:1<29::AID-IJC6>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Balis FM, Holcenberg JS, Bleyer WA. Clinical pharmacokinetics of commonly used anticancer drugs. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1983;8:202–232. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198308030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.