Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenous, non-coding RNA transcripts that regulate gene expression. Here, we report 175 putative novel miRNAs identified in uterine cancers profiled by Next Generation Sequencing. Our data indicate that one of these putative miRNAs (BCM-173) is conserved across multiple species and is expressed at levels similar to known human miRNAs. Functionally, this miRNA promotes the growth and migration of uterine cancer cell lines by targeting vinculin and altering the distribution of focal adhesions. These results expand our insight into the repertoire of human miRNAs and identify novel pathways by which dysregulated miRNA expression promotes uterine cancer growth.

Keywords: MicroRNA, Uterine Cancer, Vinculin, Focal adhesions, Migration

1. INTRODUCTION

Uterine cancer is the most common malignancy diagnosed in the female reproductive tract. More than 42,000 women are newly diagnosed with this disease each year. [1] Obesity, metabolic syndrome, nulliparity and estrogen exposure are well-recognized risk factors for this disease. However, the specific mechanisms by which these risk factors and other genetic events lead to endometrial cancer remain poorly understood.

Altered expression of small, non-coding RNA transcripts known as microRNAs (miRNAs) are a common feature of solid human tumors. [2] In general, miRNAs play an important role in regulating endometrial growth and regeneration. Recent evidence indicates that miRNA processing and expression are directly impacted by the cyclic fluctuations of steroid hormones that occur during the menstrual cycle and that altered levels of miRNA expression play important roles in endometrial decidualization. [3] Our group and others have also shown that altered miRNA expression contributes to the ectopic growth of endometrial tissue in endometriosis [4; 5; 6]. Given that miRNAs play an important role in regulating normal endometrial function, it seems feasible that altered miRNA expression contributes to the initiation and/or progression of uterine cancer. A number of studies have recently shown that different uterine cancer histotypes are characterized by distinct patterns of altered miRNA expression. [7] Consistent with these observations, expression of two miRNA processing enzymes (Dicer and Drosha) is frequently down-regulated in uterine cancer and correlate with uterine cancer outcomes. [8; 9] However, the specific miRNAs involved in driving uterine cancer and the mechanisms by which altered expression of these transcripts promote endometrial carcinogenesis remain poorly understood.

Recently, we used Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) to profile the small RNA transcripts found in specimens of an aggressive histotype of uterine cancer known as uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC). UPSC occur more frequently in African-American or Hispanic women, are less likely to present with symptoms of postmenopausal bleeding, and metastasize earlier than other types of uterine cancer such as well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinomas [10]. Current models propose that UPSC are initiated in resting endometrium in morphologically normal cells characterized by abnormal TP53 function.[11; 12; 13] These abnormal cells develop into microscopically visible dysplastic lesions (endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia ”EIN) characterized by a spectrum of molecular abnormalities that distinguish them from the types of hyperplastic endometrial lesions that lead to much more common endometrioid adenocarcinomas.[11] [13] [14] Emphasizing their distinct pathogenesis, UPSC and other aggressive endometrial cancer histotypes such as clear cell carcinomas are now categorized as “Type II” uterine cancers. As part of our earlier work examining patterns of miRNA expression in uterine cancers, we found that UPSCs are characterized by an abundance of small RNA transcripts that do not map to known microRNAs or other types of coding or non-coding RNA transcripts. These observations led us to hypothesize that the dysregulated expression of novel microRNA loci might contribute to the growth and/or metastasis of UPSC. To test this hypothesis, we modified a bioinformatic platform previously developed by our group and used this platform to examine the pool of ~33 million unknown transcripts from our initial analyses [15].

Here, we report 175 putative novel microRNAs that we identified by the application of our bioinformatic platform. To validate our analyses, we selected the most abundant putative novel miRNA we identified for further study. Our results indicate that this transcript (BCM-173) functions as a miRNA and that increased levels of its expression promote the growth of established UPSC cell lines by targeting vinculin and altering the distribution of focal adhesions. These observations expand our understanding of the repertoire of human microRNAs and identify a novel mechanism by which altered miRNA expression contributes to the progression of UPSC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 RNA Extraction and Small RNA sequencing

Total RNA was isolated using mirVana miRNA Isolation kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). For all specimens, RNA quality was assessed using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). Only specimens with an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥ 8.0 and 28S:18S rRNA ratio ≥1.8 were used. Small RNA libraries were prepared using Illumina’s small RNA prep kit (v1.5) to process 1 g of total RNA according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Purified cDNA was quantified with the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and diluted to 10 nM for sequencing on the 2G Genome Analyzer (Illumina) by the Institute of Molecular Design Sequencing Center at the University of Houston (Houston, Texas).

2.2 Novel miRNA Discovery

Sequence reads obtained from individual runs were filtered and mapped to known human miRNA hairpins using mirBase (v17). The remaining small RNA transcripts were evaluated using a previously described platform.[15] Because many of these transcripts were partial, we extracted 200 base pairs (bp) of genomic sequence immediately flanking either the 3′ or 5′ end of each transcript being studied using UCSC Human Genome Browser (v19; Date of access: September 3, 2011). Retrieved sequences were then assessed for their secondary structure using RNAfold (Vienna RNA folding package). If a small RNA did not align to a fold-back structure, it was discarded. Any remaining sequences were trimmed to 60 – 150 nucleotides in length and refolded in silico to determine whether the same hairpin structure was still energetically favored. Once this had been confirmed, three criteria were used to assess whether the hairpins we had identified were consistent with a microRNA precursor. First, the sequence for a putative miRNA had to align on one side of its predicted precursor. Second, the putative miRNA had to bind at least 16 bases of the contralateral strand of the precursor hairpin along its first 22 nt. Third, the predicted hairpin sequence should have a minimum free energy for folding no greater than −25 kcal/mol. We examined each putative hairpin structure for possible Drosha and Dicer processing sites. [16] Sequences were categorized as either “High”, “Medium”, “Low” based on the degree to which they fulfilled 4 additional criteria: 1) termination of the 3′ end of a 5p sequence 6-10 bp from the loop generated by RNA fold-back, 2) initiation of the 5′ end of a 3p sequence 6-10 bp from precursor loop, 3) presence of a hairpin loop that contains 11-20 nts, 4) identification of both 5p and 3p transcripts with only +3 nt variability. Sequences that fulfilled all 4 criteria were classified as “High” probability microRNAs. Sequences meeting criteria 1, 2 and 3 were classified as “medium” probability microRNAs. Any remaining sequences were categorized as low probability miRNAs. Gene targets for putative microRNAs were predicted using TargetScan Custom (http://www.targetscan.org) and Diana Target Prediction Software (http://diana.cslab.ece.ntua.gr/) [17].

2.3 Conservation of microRNA Transcripts

Candidate miRNA sequences were blatted against the reference human genome using the UCSC genome browser. To determine whether a novel sequence is conserved, the nucleotides at positions 2-6 of the 5′ end of each human sequence were compared to the reference genomes of 46 distinct vertebrate species using the PHAST package, a combination of the PhastCons and phyloP algorithms [18]. A sequence was considered to be conserved in primates, placental mammals and/or vertebrates if at least three species had 100% conservation to the reference human sequence.

2.4 Reverse Transcription and Real Time PCR

After isolating total RNA, cDNA was synthesized from 100 ng of total RNA using qScript cDNA Supermix (Quanta BioSciences, Inc, Gaithersburg, MD). For gene expression, quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using Taqman assays according to the manufacturer’s instructions using GAPDH as the control (Applied Biosystems). To analyze relative levels of BCM-173 expression, cDNA was prepared from 10 ng RNA with the MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems) using custom miRNA Taqman primers designed to detect GCAGUGACUGUUCAGACGUCC (Applied Biosystems). Expression of U6 was used as a control. Relative levels of miRNA or gene expression were quantified using the ΔΔCT method, using either U6 or GAPDH as an internal control to normalize the expression data [19].

2.5 Cell Culture and Transfection

Cultures of UPSC-ARK1, UPSC-ARK2 were obtained from A. Santin (Yale University).[20] HEK293T were obtained from the tissue culture core at Baylor College of Medicine. All lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Hyclone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (PAA Laboratory, Pasching, Austria) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY). Transfection of cell lines was performed using a custom synthesized single-stranded mimic (GCAGUGACUGUUCAGACGUCC) of BCM-173 or non-targeting microRNA control (Dharmacon, Inc, Chicago, IL). 2.5 × 105 cells were plated in each well of a 6-well plate and reverse transfected with either 25, 50, 75 or 100 nM of BCM-173 custom mimic or non-targeting mimic control with 4 l of lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) at 37°C at 5% CO2 for 48 hours. All transfection media were prepared using OptiMEM media (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY).

2.6 Cell Assays

Forty-eight hours after transfection, 750 cells in 100 l of complete media were replated into 96-well plates to assay proliferation (Cell-Titer 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay) or apoptosis (Caspase Glo 3/7 Assay) (Promega, Madison, WI). Colony assays were performed by plating 200 cells from each transfection condition/well in complete media. After 2 weeks, cells were fixed and stained with 6% glutaraldehyde in 0.05% crystal violet. Results are reported as the mean number of colonies observed per well. Cell migration was performed using a standard scratch assay [21]. An EVOS microscope (AMG, Bothell, WA) was used to record images in 3 fields at each specified time point. Means were compared by 2-way ANOVA. . Reporter assays for 3′UTR binding were performed using a custom lucerifase reporter vectors containing the intact 3′-UTR for Vcl gene as well as single site and double site mutations in the 3′UTR (Origene, Rockville, MD) using Steady-Glo assay system (Promega, Madison, WI). Western blots were performed using 4-12% gradient polyacrylamide gels (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Rabbit anti-vinculin antibody and goat anti-rabbit-FITC were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Anti-GAPDH antibody and anti- -tubulin- Alexa555 were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), and Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA), respectively. Slides for immunofluorescense utilized the same antibodies and were mounted using VECTASHIELD mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Immunofluorescence images were taken with an EVOS microscope.

3. Results

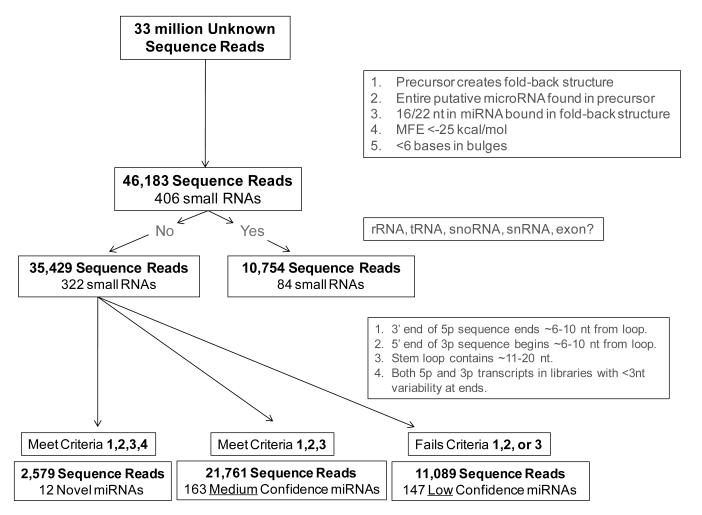

We recently profiled patterns of non-coding RNA transcripts in 6 specimens of primary, untreated uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC) as well as 8 specimens of healthy endometrium using Next Generation Sequencing. Basic clinical demographics for the UPSC specimens utilized for this studies are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. We obtained 10-21 million usable sequence reads from each of the specimens we profiled. These results indicated that UPSC are characterized by an abundance of small RNAs that do not map to known human miRNAs or other types of known non-coding RNA transcripts. On average, 38 + 7% of the small RNA reads we recovered from specimens of UPSC were unique transcripts that did not map to any known human microRNA (Range: 26-43%). This proportion was significantly greater than the proportion of unknown reads observed in normal healthy human endometrium (29 + 5% total reads, Range: 23-36%, p = 0.04) and other cancer specimens we have previously studied. [4; 22] We hypothesized that at least some of unknown transcripts we identified in UPSC were novel miRNAs. To explore this hypothesis, we initially parsed our pool of unidentified RNA transcripts to determine whether they conform to the biophysical criteria expected of a miRNA. In part, our algorithm relied on criteria established by Ambros to distinguish miRNAs from other types of small RNA transcripts [23]. We also evaluated transcripts using a number of other commonly accepted criteria designed to insure that the precursors we identified conformed to the expected structure of miRNA (Figure 1). These criteria included a minimum free energy for folding (MFE) ≤ −25 kcal/mole and predicted binding of at least 16 of the 22 nt in the mature guide strand of each putative miRNA to complementary bases in favored fold-back structure created by its precursor.

Figure 1. Analysis of unknown small RNA sequence reads from endometrium and UPSC.

The pool of 33 million unknown transcripts recovered from small RNA sequencing libraries created from healthy endometrium and UPSC were parsed according to established criteria expected of miRNAs (see insets).

Upon completing these analyses, we were left with a total of 35,429 miRNA candidates representing 322 distinct transcripts. These sequence reads accounted for <1% of the total reads analyzed. We were able to identify a passenger strand or a complementary sequence (3p-strand or miR*) in our cloning libraries for 12 of these transcripts (10 from UPSC and 2 from endometrium). Given that each of these 12 transcripts fulfilled the criteria used to define miRNAs, we categorized them as “high” confidence novel miRNAs. The full-length mature sequence for these transcripts as well as their chromosomal location and the genomic orientation of their precursors are listed in Table 1. Only a minority of the novel miRNAs we identified (3 of 12) are located in intergenic regions. Instead, precursors for most of these transcripts are located in the introns of known protein-coding genes. Because these sequences do not align with recognized splice sites for their host genes, these putative novel miRNAs cannot be considered mirtrons. We also identified another 21,761 sequence reads representing 163 distinct transcripts that fulfilled the criteria expected of a miRNA except that a 3p-strand (miR*) sequence could not be identified. MiR* sequences are typically degraded and therefore found at lower abundance than the active guide miRNA from the same stem-loop precursor. We predict that these transcripts are also genuine novel miRNAs and have categorized them as “medium” probability candidate miRNAs. Their sequences, genomic locations, and orientations can be found in Supplementary Table 2. Lastly, we identified 11,089 sequence reads representing 147 distinct transcripts (data not shown). Transcripts in this latter category were characterized by their ability to create a fold-back structure, but did not conform to other criteria expected of miRNAs. These transcripts are unlikely to represent miRNAs and are classified as “low” probability candidates.

Table 1. Genomic location of high-probability novel microRNAs from endometrium and UPSC.

Location refers to the genomic location of each putative novel miRNA relative to nearest, known protein-coding genes. The genomic position of each putative miRNA locus is identified according to chromosome number, position, and strand (+1 vs. −1). Corresponding gene symbol identified in parentheses.

| Number | Putative Mature miRNA |

Hairpin Location |

Chromosome Position; Strand |

miR Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPSC Novel MicroRNA | ||||

| 36 | AGGATGGAAAAGATGAATTCAT | Intergenic | Chr 2: 76268318 - 76268457; +1 | Novel |

| 173 | GCAGTGACTGTTCAGACGTCC | Intergenic | Chr 1: 98283397 - 98283491; −1 | IsomiR-2682 |

| 194 | ACTTGTAATGGAGAACACTAAGC | Intronic (MLLT3, −1) | Chr 9: 20401145 - 20401236; −1 | Novel* (miR-4473-3p) |

| 210 | TCAGGTGTGGAAACTGAGGCAG | Intronic (C6orf125,−1); | Chr 6: 33773891 - 33773980; −1 | Novel |

| 229 | TCCACATGTAAAAAAATGAATC | Intronic (KCNK2, +1) | Chr 1: 63739341 - 63739428; +1 | Novel |

| 277 | TATATAGTATATGTGCATGTAT | Intergenic | Chr 10: 9401009 - 9401091; −1 | Novel |

| 299 | TCTGTGAGACCAAAGAACTACT | Intronic (SDCCAG8, +1) | Chr 1: 241576101 - 241576180; +1 | miR-4677 |

| 324 | TGGCTATCTCACGAGACTGTAT | Intronic (CACHD1, +1) | Chr 1: 64818118 - 64818194; +1 | Novel* (miR-4794-3p) |

| 326 | TTAGTTCTGTGGCAACATCGA | Intronic (RALGPS2, +1) | Chr 1: 176979303 - 176979379; +1 | Novel |

| 351 | TGGGGTGCCCACTCCGCAAGTT | Intronic (FAM83H, +1) | Chr 8: 144887241 - 144887311; −1 | miR-4664 |

| Endometrial Novel MicroRNA | ||||

| 13 | TGAACAACAGTATACACCAAAT | Intronic (KCNIP4,+1) | Chr 4: 21075368-21075531; −1 | Novel |

| 248 | TGTGTGTGCATGGATATATAT | Intronic (EPHA6,+1) | Chr 3: 98285609-98285694; +1 | Novel |

While preparing this material for publication, we again used the UCSC Genome Browser to determine whether any of the putative novel miRNAs we had identified had been reported by others in the interval since we began our analysis. We found that 3 of 12 confirmed novel miRNAs we identified have now been reported by other investigators in one or more human tissues. Two of the 12 novel transcripts we identified also appeared to be isomiRs of recently reported miRNAs. Their identity is noted in Table 1. Star sequences for these transcripts were not detected by other investigators. For two of the previously reported microRNAs, miR-4473 and miR-4664, we were able to identify star sequences in the UPSC specimens. For BCM-173 (a potential isomiR of miR-2682), deep sequencing of melanoma specimens identified only the 3p-strand for BCM-173 without identifying a mature guide strand [24]. Although BCM-173 is found on the same hairpin encoded by miR-2682, it is expressed in higher levels than mature transcripts for miR-2682 in uterine cancers. We also found that 22 of our 163 “medium”-confidence candidate miRNAs have been recently reported by others. These are listed separately at the bottom of Supplemental Table 2. Similar to our confirmed novel miRNAs, the investigators reporting these candidate miRNAs were limited to their sequences and an analysis of secondary structure.

To examine whether the candidate miR precursors we identified were capable of creating a secondary structure suitable for Dicer processing, we used RNAfold to examine the free energies for different conformations and determine the structure associated with the minimum free energy for folding (MFE) for each high confidence novel miRNA precursor we identified. In each case, the fold-back structure most likely to generate the mature miRNA identified from our sequencing libraries was energetically favored, with MFEs ranging between −54.4 kcal/mole and −31.0 kcal/mole (Supplemental Figure 1). These observations indicate that the precursors we defined fold into structures that can be processed by Dicer to release mature microRNAs.

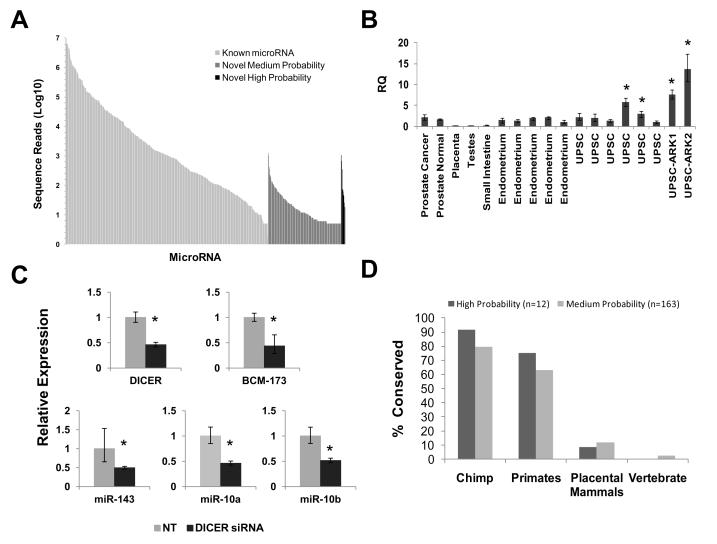

Because criteria used to define miRNAs remain somewhat imprecise, we chose to assess whether the transcripts being studied are biologically plausible miRNAs in a number of different ways. First, we compared the frequency of read counts for each putative novel miRNA found in our sequencing libraries to those for known human miRNAs in the same specimens. We have previously identified 345 individual known human miRNAs in endometrium and UPSC with read counts/specimen ranging from 5 to 5.2 × 105/specimen. Read counts for our high-confidence novel miRNAs were similar to many known human miRNAs identified in these same libraries (Figure 2A). Despite the fact that we were unable to identify a 3p-strand for the 163 medium-confidence candidate miRNAs we discovered, these specimens were found with similar frequency as many known miRNAs. We next selected one of these putative miRNAs (BCM-173) for further study. This choice was made because this high-confidence novel miRNA had the highest read count of any of the novel transcripts identified in our specimens, could be detected in multiple small RNA cloning libraries we created from other reproductive tract tissues (ovary, myometrium, leiomyoma; data not shown), and has been recently detected by other investigators. Of note, 3p-strands (miR*) for BCM-173 have been detected by our group in specimens of UPSC, suggesting that its expression might be higher in these cancers than other tissues. We used custom Taqman miRNA assay to probed RNA prepared from a panel of human tissues and select human cancers for mature BCM-173 transcripts. We were able to reliably detect BCM-173 in all specimens of healthy endometrium (n=5) and primary uterine papillary serous carcinoma that we tested (Fig. 2B). Of note, levels of BCM-173 were elevated in 2 of the 6 UPSC specimens when compared to specimens of healthy endometrium (Fig. 2B, p<0.01) (Figure 2B), This observation suggests that the overexpression of this putative novel miRNA contributes to the pathogenesis of at least a subset of UPSC. High levels of BCM-173 were also observed in two established UPSC cell lines, UPSC-ARK1 and UPSC-ARK2. We were also able to detect the BCM-173 transcript in normal prostate (n=5) and prostate cancers (n=10) at levels comparable to endometrium. Low levels of BCM-173 were found in placenta, testes and small intestine while BCM-173 was undetectable in spleen, thymus and thyroid (Figure 2B). BCM-173 was undetectable in specimens of endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinomas (n=6).

Figure 2. BCM-173 and novel miRNA expression in UPSC and established UPSC cell lines.

(A) Frequency of read counts for all unique microRNA species identified in our cloning libraries by Next Generation Sequencing. Note that frequency of both “high” and “medium”-probability novel miRNAs are similar to that observed for known human microRNAs in our specimens. (B) Real-time qPCR was used to confirm that the predicted mature transcripts for BCM-173 can be detected in human prostate cancers, normal prostate, placenta, testes, small intestine, endometrium and UPSC. Results are reported as expression relative to fifth endometrial specimen. (C) Targeting Dicer expression by siRNA reduces the expression of BCM-173, as well as other known human miRNAs (miR-143, miR10a/b). (D) Conservation of high- and medium-probability novel miRNAs was determined by blatting the seed sequence for each predicted mature miRNA using the USCS Genome Browser. An individual miRNA was considered conserved if it could be detected in 3 or more species in each category.

To determine whether BCM-173 is a product of Dicer-mediated RNA processing, we used siRNA to target Dicer expression in UPSC-ARK1 and ARK2 cells. Cultures transfected with an siRNAs targeting Dicer demonstrated significantly reduced expression not only of Dicer and BCM-173 but also other known human microRNAs, such as miR-10a/b and miR-143 (n=3; p<0.01; Figure 2C). These results indicate that the expression of BCM-173 is dependent on processing by Dicer, as expected for a functional human miRNA. Lastly, we asked whether the high- and medium-confidence microRNAs we identified are phylogenetically conserved. Conservation across species has been used by a number of investigators to assess the likelihood that a given small RNA encodes a biologically significant microRNA. We blatted the predicted mature seed sequences for each our high- and medium-confidence microRNAs using the USCS Genome Browser (v19) to search multiple species and phyla. We found that each of the 12 high-probability novel microRNA transcripts as well as many of the medium confidence microRNAs we identified are conserved across multiple placental and non-placental mammals. The frequency with which our high- and medium-probability putative microRNAs are conserved appears similar (Figure 2D).

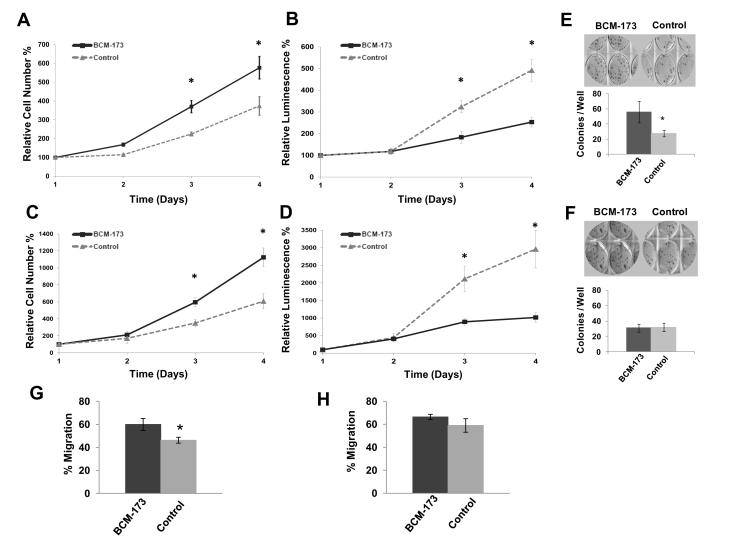

To further assess whether the transcripts we detected represent functional microRNAs, we transfected two UPSC cell lines with a custom mimic for BCM-173.[20] We found that BCM-173 increased proliferation and inhibited apoptosis when transfected into both UPSC-ARK1 and UPSC-ARK2. On average, mimics for BCM-173 increased proliferation ~1.5-fold 96 hours after transfection (n=4, p<0.01) when compared to control cultures of UPSC-ARK1 either sham-transfected (data not shown) or transfected with a non-targeting mimic control (Figure 3A). BCM-173 also inhibited apoptosis ~2–fold (n=4, p<0.01) (Figure 3B). Similar results were observed with UPSC-ARK2 cells, where mimics for BCM-173 increased proliferation 1.9-fold (n=4, p<0.01) and inhibited apoptosis 3-fold (n=4, p<0.01) (Figure 3C, D). Lastly, we found that mimics for BCM-173 increased colony formation with UPSC-ARK1 cells ~2-fold (n=3, p<0.01, Figure 3E) and increased cell migration as measured by the percentage of a scratch made in confluent cells occluded at 24 hours in ARK1 cells (Figure 3G). Potentially reflecting the unique genetic environment in these cells, BCM-173 had no impact on colony formation or migration in UPSC-ARK2 cells (Figure 3E,H).

Figure 3. Impact of BCM-173 on proliferation, apoptosis, colony formation and migration in established UPSC cell lines.

Cultures of UPSC ARK-1 (A, B) and ARK-2 (C, D) cells were transfected with either a mimic for BCM-173 or a non-targeting mimic control. Proliferation (A, C) is reported as relative cell number normalized to Day 0 values for each cell line. Apoptosis (B, D) is reported as relative luminescence also normalized to Day 0 values. Cultures of UPSC ARK-1 (E) and ARK-2 (F) cells were transfected with either a mimic for BCM-173 or a non-targeting mimic control. Colonies formed by UPSC-ARK1 or UPSC-ARK2 transfected with BCM-173 mimic or control were counted manually after fixation with glutaraldehyde and staining with crystal violet (E,F) and are reported as mean number of colonies/well (*p<0.01). A scratch assay to evaluate the impact of BCM-173 on cell migration was performed following transfection of each cell line with either control or BCM-173 mimic. Percentage of the scratch occluded was measured 24 hours for UPSC-ARK1 (G) and at 12 hours for UPSC-ARK2 (H) as compared to the 0 hour time point for both cell lines was measured in triplicate (*p<0.01).

To examine how BCM-173 impacts UPSC growth and metastasis, we used Targetscan Custom to identify potential targets using the putative seed (CAGUGAC) for BCM-173. This analysis identified 272 potential targets (Supplemental Table 3). Using the Ingenuity and Diana software [25], we found that many of these predicted targets have been previously implicated in cell adhesion and migration (CLDN1, CABLES2, RAB39B, RAB33B, CALD1, SYT14), nucleotide metabolism (CDADC1, ELL, UCK1), cell signaling (MAPK1, GNAI2), and hypoxia (HIFAN) solute transport. A number of these, including C-MET, RRAS, and V-MAF, have been previously implicated as oncogenes [26; 27] and at least one (GABRA6) is frequently mutated in high-grade papillary serous carcinomas of the ovary [28]. Given the preponderance of gene products implicated in cell adhesion and migration among the predicted targets for BCM-173, we focused our attention on vinculin (VCL), a key protein critical for bridging sites of cell adhesion to the intracellular cytoskeleton [29].

Although altered expression of VCL has been implicated in other human cancers, levels of its expression in uterine cancer have not been previously studied. Therefore, we first examined VCL levels in endometrium, specimens of UPSC and established UPSC cell lines. We found that overall levels of VCL transcript (Fig 4A) and gene product (data not shown) were significantly lower in UPSC and UPSC cell lines than endometrium. Next, we transfected UPSC-ARK1 or UPSC-ARK2 with BCM-173 mimic or a non-targeting mimic control and examined the location and frequency of focal adhesions by performing immunocytochemistry with an antibody that specifically recognized vinculin (Figure 4B, C). In cultures transfected with non-targeting miRNA control, 95% of cells counted had >10 focal adhesions and that the majority of these adhesions were located centrally. (Figure 4D, E). In cultures transfected with BCM-173, the number of cells containing >10 focal adhesions had decreased ~50% and 80% of those remaining focal adhesions were located at the periphery of the cells along lamellipodia.

Figure 4. BCM-173 alters focal adhesions in UPSC cell lines.

Levels of VCL expression of endometrium and UPSC using real-time qPCR (A). Focal adhesions in UPSC cell lines were visualized using antibodies specific for either vinculin (green stain) or actin (red stain). Nuclei are stained by DAPI (blue) Representative photomicrographs demonstrate that distribution and number of focal adhesions is significantly different in cultures of UPSC-ARK1 transfected with BCM-173 (C) than non-targeting control (B). For both sets of images, green: vinculin; Red: actin; Blue: DAPI. Large images: 20X; Inset: 40X magnification. The distribution and number of focal adhesions are reported as the percentage of cells with 10 or more visible focal adhesions (D) and the presence of detectable central focal adhesions (E).

Intrigued by these results, we examined whether BCM-173 was able to directly target the VCL transcript, resulting in reduced levels of its expression. Our prior experience with the use of hairpin miRNA inhibitors suggests that miRNA inhibitors work poorly when mature miRNAs are expressed at read counts <50,000 transcripts/specimen. Because read counts for BCM-173 were uniformly lower than this threshold, we elected to explore the potential biologic function for this putative novel miRNA using mimics rather than inhibitors. We found that enforced expression of BCM-173 in both UPSC-ARK1 and UPSC-ARK2 significantly decreased endogenous vinculin expression regardless of whether VCL expression was measured by real-time qPCR (Figure 5A, data for UPSC-ARK1 shown) or Western blot (Figure 5B). To confirm that reduced expression of VCL observed in response to BCM-173 is due to a direct interaction with the VCL mRNA, we transfected HEK293T cells with a luciferase reporter plasmid regulated by 3′UTR of the human VCL mRNA transcript. We found that synthetic mimics for BCM-173 (Figure 5C) reduced luciferase expression when compared to mimic control (Figure 5D), consistent with our hypothesis that BCM-173 bind to the 3′ UTR of the VCL transcript, leading to translational inhibition. Using BLAST software to search the 3′UTR of VCL, we identified two potential binding sites complementary to the seed of our putative miRNA candidate. We found that mutations in first but not the second of these binding site ameliorated luciferase reporter activity (Figure 5E, F, G). These results confirm that BCM-173 binds directly to the VCL transcript.

Figure 5. BCM-173 directly binds to the VCL transcript via its predicted seed sequence.

Vinculin expression in UPSC-ARK1 cultures transfected with BCM-173 mimic or a non-targeting mimic control was compared using real-time qPCR (A) or Western blot (B). (*p<0.01) The predicted pairing of the BCM-173 seed sequence to both complementary binding sequences in the 3′UTR of VCL is shown (C). Interactions between BCM-173 and the 3′-UTR of the vinculin mRNA were examined using a luciferase reporter assay designed to detect complementarity of the BCM-173 seed sequence to the 2 target sites in the 3′UTR of VCL with results are expressed as relative light units (RLU; C; *p<0.02). Binding sites were evaluated as follows: (D) both binding sites intact, (E) first binding site mutated, second binding site intact (F) second binding site mutated, first binding site intact and (G) both binding sites mutated.

4. Discussion

Since the first description of small interfering RNA pathways more than a decade ago, an intense period of exploration has identified a wide variety of novel genomic messages that play important roles in human development and disease. Different strategies, ranging from forward genetic screens to the bioinformatic screening of genomes for structural motifs have all been successfully used to identify miRNAs in humans and other organisms [30; 31; 32; 33; 34]. As cells and tissues are being profiled much more deeply with Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and other technologies, candidate miRNAs are being discovered with increasing frequency [15; 35; 36; 37]. However, the biologic relevance of the transcripts identified by these strategies is often unclear, especially for transcripts expressed at low abundance [38]. In most circumstances, very little is done to validate their biologic function. This situation is complicated by the fact that the criteria used to define microRNAs remains unsettled [38]. At least one recent analysis has questioned the relevance of many of the putative miRNAs recently discovered in humans, mice and other species, suggesting that their lack of conservation across phyla and low levels of expression preclude significant biologic roles [39]. However, multiple reports in the literature have documented biologic function for miRNAs often expressed at very low abundance.

In the present work, we have identified at least 6 novel miRNAs for which the presence of a corresponding 3p-strand (miR*) could be detected in specimens of UPSC. Our ability to detect the presence of a 3p-strand (miR*) for each of these miRNAs in our sequencing libraries indicates that processing of the fold-back precursor predicted by our analyses is correct and confirms that these transcripts are novel miRNAs [23]. We have also have identified an additional 164 putative novel miRNAs for which we could not detect 3p-strand (miR*) sequences. Our inability to detect miR* for these transcripts is likely due to the low levels of their expression. Nonetheless, we believe that these transcripts also represent novel miRNAs, particularly considering the stringent criteria we used to perform our bioinformatic screen.

To further validate our analytic approach, we selected the most abundant of the novel confirmed putative miRNAs (BCM-173) we identified for further study. Our results clearly indicate BCM-173 is capable of targeting gene expression via its predicted seed sequence as would be expected for a miRNA. These results provide powerful functional evidence that our bioinformatic predictions are accurate. It is noteworthy that BCM-173 appears structurally similar to a previously reported human miRNA (miR-2682). This similarity led us to question whether BCM-173 is an isomiR of miR-2682 or vice versa. Currently, the relationship between miRs and isomiRs is defined by number of transcripts expressed for each transcript in a tissue. The fact that BCM-173 can be detected at significantly higher levels than miR-2682 suggests that this transcript should be considered the parent miR in endometrium.

The biologic relevance of our observations is supported by our finding that BCM-173 is capable of targeting vinculin, altering the distribution of focal adhesions and impacting migration in vitro. Typically, vinculin localizes to sites of contact between two cells or a cell and its extracellular matrix. At both locations, vinculin links transmembrane receptors such as integrins and cadherins to the actin cytoskeleton [40]. Altered vinculin expression has been reported in a number of cancers, including carcinomas of the breast, colon, prostate, and lung [41]. In hepatic carcinomas, decreased vinculin expression enhances cell motility and proliferation by altering the function of focal adhesion kinase and promoting cell migration and survival [42]. However, a report studying prostate cancer suggests that vinculin overexpression may enhance proliferative activity in a subset of castration-resistant cancers. In this latter report, vinculin may be regulating proliferation independent of its ability to interact with focal cell adhesions (42). Our data clearly indicate that levels of vinculin expression in UPSC are markedly reduced in UPSC. However, the mechanisms by which a loss of vinculin expression promotes migration and/or metastasis in UPSC are not yet clear. Ultimately, the pathways dysregulated as a result of altered BCM-173 expression will require further dissection. Given the established ability of miRNAs to simultaneously target multiple gene products, it is entirely possible that BCM-173 promotes uterine cancer migration and metastasis by functioning in tandem with multiple other genetic events.

In conclusion, our results have identified a large number of putative and confirmed novel miRNAs that likely contribute to UPSC. The precise roles that these transcripts play in UPSC, their contribution to endometrial function and/or their role in other human tissues and diseases remain will continue to be clarified in the future.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Favored secondary structures for high probability novel microRNAs. Secondary structures associated with precursors for high probability putative microRNAs was examined using RNAfold program. Putative Dicer cut sites are denoted by lines. Putative Drosha cut sites are denoted by arrows.

Supplemental Table 1. Demographic Features Associated Uterine Papillary Serous Carcinoma Specimens Studied.

Supplemental Table 2. Medium Confidence Novel microRNAs. Transcripts recently identified by others noted at bottom.

Supplemental Table 3. Predicted Targets for BCM-173. Putative targets for BCM-173 were identified by using Targetscan Custom using the seed sequence CAGUGAC.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Program Project Development Grant from the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund (MLA, PHG), Young Texans Against Cancer (MLA), K12 HD01426-02 (MLA), Saks Fifth Avenue “Key to a Cure” (MLA), the Specialized Cooperative Centers in Reproductive & Infertility Research U54HD07495 (SMH, PHG), National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant P30CA125123 (CJC) and Women’s Cancer Foundation Carol’s Cause Endometrial Cancer Research Grant (CMM, MLA). Funding agencies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

6. Conflict of Interest The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

7. Author Contributions Conceived and designed the experiments: JK, CM, MLA. Performed the experiments: JK, CM, BS, MLA. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: JK, CM, PS, IZ, PG, CJC, KO, SH, PHG, MLA. Wrote the paper: CM, SH, PS, MLA.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, Stein K, Mariotto A, Smith T, Cooper D, Gansler T, Lerro C, Fedewa S, Lin C, Leach C, Cannady RS, Cho H, Scoppa S, Hachey M, Kirch R, Jemal A, Ward E. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:220–241. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Slack FJ, Weidhaas JB. MicroRNA in cancer prognosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;359:2720–2722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0808667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lam EW, Shah K, Brosens JJ. The diversity of sex steroid action: the role of micro-RNAs and FOXO transcription factors in cycling endometrium and cancer. The Journal of endocrinology. 2012;212:13–25. doi: 10.1530/JOE-10-0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hawkins SM, Creighton CJ, Han DY, Zariff A, Anderson ML, Gunaratne PH, Matzuk MM. Functional MicroRNA Involved in Endometriosis. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:821–832. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Filigheddu N, Gregnanin I, Porporato PE, Surico D, Perego B, Galli L, Patrignani C, Graziani A, Surico N. Differential expression of microRNAs between eutopic and ectopic endometrium in ovarian endometriosis. Journal of biomedicine & biotechnology. 2010;2010:369549. doi: 10.1155/2010/369549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pan Q, Luo X, Toloubeydokhti T, Chegini N. The expression profile of micro-RNA in endometrium and endometriosis and the influence of ovarian steroids on their expression. Molecular Human Reproduction. 2007;13:797–806. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gam063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Devor EJ, Hovey AM, Goodheart MJ, Ramachandran S, Leslie KK. microRNA expression profiling of endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinomas and serous adenocarcinomas reveals profiles containing shared, unique and differentiating groups of microRNAs. Oncology reports. 2011;26:995–1002. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pan Q, Luo X, Chegini N. Differential expression of microRNAs in myometrium and leiomyomas and regulation by ovarian steroids. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2008;12:227–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [9].Zighelboim I, Reinhart AJ, Gao F, Schmidt AP, Mutch DG, Thaker PH, Goodfellow PJ. DICER1 expression and outcomes in endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2011;117:1446–1453. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fader AN, Boruta D, Olawaiye AB, Gehrig PA. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: epidemiology, pathogenesis and management. Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology. 2010;22:21–29. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328334d8a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zheng W, Xiang L, Fadare O, Kong B. A proposed model for endometrial serous carcinogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:e1–e14. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318202772e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fadare O, Liang SX, Ulukus EC, Chambers SK, Zheng W. Precursors of endometrial clear cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1519–1530. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213296.88778.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zheng W, Liang SX, Yu H, Rutherford T, Chambers SK, Schwartz PE. Endometrial glandular dysplasia: a newly defined precursor lesion of uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Part I: morphologic features. Int J Surg Pathol. 2004;12:207–223. doi: 10.1177/106689690401200302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Liang SX, Chambers SK, Cheng L, Zhang S, Zhou Y, Zheng W. Endometrial glandular dysplasia: a putative precursor lesion of uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Part II: molecular features. Int J Surg Pathol. 2004;12:319–331. doi: 10.1177/106689690401200405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Creighton CJ, Benham AL, Zhu H, Khan MF, Reid JG, Nagaraja AK, Fountain MD, Dziadek O, Han D, Ma L, Kim J, Hawkins SM, Anderson ML, Matzuk MM, Gunaratne PH. Discovery of novel microRNAs in female reproductive tract using next generation sequencing. PloS one. 2010;5:e9637. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Helvik SA, Snove O, Jr., Saetrom P. Reliable prediction of Drosha processing sites improves microRNA gene prediction. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:142–149. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Maragkakis M, Alexiou P, Papadopoulos GL, Reczko M, Dalamagas T, Giannopoulos G, Goumas G, Koukis E, Kourtis K, Simossis VA, Sethupathy P, Vergoulis T, Koziris N, Sellis T, Tsanakas P, Hatzigeorgiou AG. Accurate microRNA target prediction correlates with protein repression levels. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:295. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hubisz MJ, Pollard KS, Siepel A. PHAST and RPHAST: phylogenetic analysis with space/time models. Briefings in bioinformatics. 2011;12:41–51. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbq072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Methods. Vol. 25. San Diego, Calif: 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method; pp. 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Cross SN, Cocco E, Bellone S, Anagnostou VK, Brower SL, Richter CE, Siegel ER, Schwartz PE, Rutherford TJ, Santin AD. Differential sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy in primary uterine serous papillary carcinoma cell lines with high vs low HER-2/neu expression in vitro. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;203:162, e161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Liang CC, Park AY, Guan JL. In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nature protocols. 2007;2:329–333. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Creighton CJ, Fountain MD, Yu Z, Nagaraja AK, Zhu H, Khan M, Olokpa E, Zariff A, Gunaratne PH, Matzuk MM, Anderson ML. Molecular profiling uncovers a p53-associated role for microRNA-31 in inhibiting the proliferation of serous ovarian carcinomas and other cancers. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1906–1915. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ambros V, Bartel B, Bartel DP, Burge CB, Carrington JC, Chen X, Dreyfuss G, Eddy SR, Griffiths-Jones S, Marshall M, Matzke M, Ruvkun G, Tuschl T. A uniform system for microRNA annotation. Rna. 2003;9:277–279. doi: 10.1261/rna.2183803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Stark MS, Tyagi S, Nancarrow DJ, Boyle GM, Cook AL, Whiteman DC, Parsons PG, Schmidt C, Sturm RA, Hayward NK. Characterization of the Melanoma miRNAome by Deep Sequencing. PloS one. 2010;5:e9685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Maragkakis M, Reczko M, Simossis VA, Alexiou P, Papadopoulos GL, Dalamagas T, Giannopoulos G, Goumas G, Koukis E, Kourtis K, Vergoulis T, Koziris N, Sellis T, Tsanakas P, Hatzigeorgiou AG. DIANA-microT web server: elucidating microRNA functions through target prediction. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37:W273–276. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wong AS, Pelech SL, Woo MM, Yim G, Rosen B, Ehlen T, Leung PC, Auersperg N. Coexpression of hepatocyte growth factor-Met: an early step in ovarian carcinogenesis? Oncogene. 2001;20:1318–1328. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Berrier AL, Mastrangelo AM, Downward J, Ginsberg M, LaFlamme SE. Activated R-ras, Rac1, PI 3-kinase and PKCepsilon can each restore cell spreading inhibited by isolated integrin beta1 cytoplasmic domains. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1549–1560. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.7.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ezzell RM, Goldmann WH, Wang N, Parashurama N, Ingber DE. Vinculin promotes cell spreading by mechanically coupling integrins to the cytoskeleton. Experimental cell research. 1997;231:14–26. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.3451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Slack FJ, Basson M, Liu Z, Ambros V, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G. The lin-41 RBCC gene acts in the C. elegans heterochronic pathway between the let-7 regulatory RNA and the LIN-29 transcription factor. Molecular cell. 2000;5:659–669. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Aravin A, Tuschl T. Identification and characterization of small RNAs involved in RNA silencing. FEBS letters. 2005;579:5830–5840. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Fu H, Tie Y, Xu C, Zhang Z, Zhu J, Shi Y, Jiang H, Sun Z, Zheng X. Identification of human fetal liver miRNAs by a novel method. FEBS letters. 2005;579:3849–3854. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Stark A, Lin MF, Kheradpour P, Pedersen JS, Parts L, Carlson JW, Crosby MA, Rasmussen MD, Roy S, Deoras AN, Ruby JG, Brennecke J, Hodges E, Hinrichs AS, Caspi A, Paten B, Park SW, Han MV, Maeder ML, Polansky BJ, Robson BE, Aerts S, van Helden J, Hassan B, Gilbert DG, Eastman DA, Rice M, Weir M, Hahn MW, Park Y, Dewey CN, Pachter L, Kent WJ, Haussler D, Lai EC, Bartel DP, Hannon GJ, Kaufman TC, Eisen MB, Clark AG, Smith D, Celniker SE, Gelbart WM, Kellis M. Discovery of functional elements in 12 Drosophila genomes using evolutionary signatures. Nature. 2007;450:219–232. doi: 10.1038/nature06340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Elemento O, Tavazoie S. Fastcompare: a nonalignment approach for genome-scale discovery of DNA and mRNA regulatory elements using network-level conservation. Methods in molecular biology. 2007;395:349–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Schotte D, Moqadam FA, Lange-Turenhout EA, Chen C, van Ijcken WF, Pieters R, den Boer ML. Discovery of new microRNAs by small RNAome deep sequencing in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:1389–1399. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Burnside J, Ouyang M, Anderson A, Bernberg E, Lu C, Meyers BC, Green PJ, Markis M, Isaacs G, Huang E, Morgan RW. Deep sequencing of chicken microRNAs. BMC genomics. 2008;9:185. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Morin RD, O’Connor MD, Griffith M, Kuchenbauer F, Delaney A, Prabhu AL, Zhao Y, McDonald H, Zeng T, Hirst M, Eaves CJ, Marra MA. Application of massively parallel sequencing to microRNA profiling and discovery in human embryonic stem cells. Genome Res. 2008;18:610–621. doi: 10.1101/gr.7179508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Berezikov E, Cuppen E, Plasterk RH. Approaches to microRNA discovery. Nature Genetics. 2006;38(Suppl):S2–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chiang HR, Schoenfeld LW, Ruby JG, Auyeung VC, Spies N, Baek D, Johnston WK, Russ C, Luo S, Babiarz JE, Blelloch R, Schroth GP, Nusbaum C, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs: experimental evaluation of novel and previously annotated genes. Genes & development. 2010;24:992–1009. doi: 10.1101/gad.1884710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Subauste MC, Nalbant P, Adamson ED, Hahn KM. Vinculin controls PTEN protein level by maintaining the interaction of the adherens junction protein beta-catenin with the scaffolding protein MAGI-2. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:5676–5681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405561200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ayaki M, Komatsu K, Mukai M, Murata K, Kameyama M, Ishiguro S, Miyoshi J, Tatsuta M, Nakamura H. Reduced expression of focal adhesion kinase in liver metastases compared with matched primary human colorectal adenocarcinomas. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2001;7:3106–3112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Raz A, Geiger B. Altered organization of cell-substrate contacts and membrane-associated cytoskeleton in tumor cell variants exhibiting different metastatic capabilities. Cancer Research. 1982;42:5183–5190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Favored secondary structures for high probability novel microRNAs. Secondary structures associated with precursors for high probability putative microRNAs was examined using RNAfold program. Putative Dicer cut sites are denoted by lines. Putative Drosha cut sites are denoted by arrows.

Supplemental Table 1. Demographic Features Associated Uterine Papillary Serous Carcinoma Specimens Studied.

Supplemental Table 2. Medium Confidence Novel microRNAs. Transcripts recently identified by others noted at bottom.

Supplemental Table 3. Predicted Targets for BCM-173. Putative targets for BCM-173 were identified by using Targetscan Custom using the seed sequence CAGUGAC.