Abstract

Regulatory T (Treg) cells are essential for self-tolerance and immune homeostasis. Lack of effector T cell (Teff) function and gain of suppressive activity by Treg are dependent on the transcriptional program induced by Foxp3. Here we report repression of SATB1, a genome organizer regulating chromatin structure and gene expression, as crucial for Treg phenotype and function. Foxp3, acting as a transcriptional repressor, directly suppressed the SATB1 locus and indirectly through induction of microRNAs that bound the SATB1 3′UTR. Release of SATB1 from Foxp3 control in Treg caused loss of suppressive function, establishment of transcriptional Teff programs and induction of Teff cytokines. These data support that inhibition of SATB1-mediated modulation of global chromatin remodelling is pivotal for maintaining Treg functionality.

Regulatory T cells (Treg) are characterized by their suppressive function and inability to produce effector cytokines upon activation1. Expression of the X-linked forkhead transcription factor Foxp3 has been clearly linked to the establishment and maintenance of Treg lineage, identity and suppressor function2–7. Moreover, Foxp3 is also associated with the control of effector T cell (Teff) function in Treg4,5. A growing body of evidence points towards plasticity amongst committed CD4+ T cell lineages, including Treg8–11, yet the mechanism for this plasticity and its significance in normal immune responses and disease states remains to be elucidated.

Multiple transgenic reporter mouse models have demonstrated that loss of Foxp3 can induce the conversion of Treg into cells with a variety of Teff programs2–4,12. While Treg are re-programmed by loss of the lineage-associated transcription factor Foxp3, there is no evidence that conventional T cells (Tconv) actively suppress the Treg lineage program. On the contrary, only stable expression of Foxp3 in Tconv appears capable of inducing a Treg phenotype within these cells7. Together these findings suggest that Teff programs are the default state in CD4+ T cells and that transcriptional programs induced and maintained by Foxp3 overrule Teff function in Treg5. Whether the inhibition of Teff differentiation in Treg is critical for Treg suppressive function is unclear. Such a model would be supported by the existence of Foxp3-induced mechanisms that continuously and actively control Teff programs in these specialized T cells.

Consistent with the active suppression of Teff programs in Treg cells, ablation of the transcriptional repressor Eos13 or the Foxo transcription factors14,15 impart partial Teff characteristics to Treg cells. Other transcription factors including IRF4 (ref. 16) and STAT3 (ref. 17) have been implicated in the modulation of effector cell differentiation by Treg cells18. There is evidence that epigenetic control as well as miRNA are important for Foxp3-mediated suppressive functions16,19–23, raising the possibility that epigenetic and post-transcriptional regulation may also be involved in the repression of Teff functions in Treg cells. These findings support the existence of active regulatory mechanisms that enable committed Treg to suppress Teff differentiation24.

In this report, we specifically searched for genes repressed by Foxp3 in Treg that might be central to maintaining regulatory function and suppression of Teff function in Treg cells. We identified the gene encoding special AT-rich sequence-binding protein-1 (SATB1) to be amongst the most significantly repressed genes in human and murine Treg cells. SATB1 is a chromatin organizer and transcription factor essential for controlling a large number of genes participating in T cell development and activation25. SATB1 regulates gene expression by directly recruiting chromatin modifying factors to its target gene loci which are tethered to the SATB1 regulatory network through specialized genomic sequences called base-unpairing regions26,27,28. In murine TH2 clones, SATB1 has been shown to function as a global transcriptional regulator specifically anchoring the looped topology of the TH2 cytokine locus, a pre-requisite for the induction of TH2 cytokines29 Since SATB1-deficient thymocytes do not develop beyond the double-positive stage25,26, the role of SATB1 in peripheral T cells, particularly in Treg, is still elusive. Repression was mediated directly by transcriptional control of Foxp3 at the SATB1 locus, by maintaining a repressive chromatin state at this locus, and indirectly by Foxp3-dependent miRNAs. Release of SATB1 from Foxp3 control was sufficient to reprogram natural Foxp3+ Treg into Teff cells that lost suppressive function and gained Teff function. These findings show that SATB1 control by Foxp3 is an essential and critical mechanism maintaining Treg cell functionality.

RESULTS

Human Treg cells express low amounts of SATB1

To identify regulatory circuits actively suppressed by Foxp3 as a prerequisite for Treg function and inhibition of Teff programs, whole transcriptome analysis of human resting or activated Tconv and natural Treg was performed (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). We identified SATB1 as of the 22 genes displaying significant lower expression in Treg compared to Tconv (Fig. 1a). Reassessment of transcriptome data from previous reports confirmed our observation of Satb1 to be a potential target of Foxp3-mediated repression30–32.

Figure 1. Foxp3-dependent repression of SATB1 expression in human Treg cells.

(a) Microarray analysis of SATB1 mRNA expression in human Tconv and Treg (Rest=resting, Act=activated, TGF=TGF-β treated, Exp=expanded). (b) Relative SATB1 mRNA expression in human Treg and Tconv. (c) Immunoblotting (left) for SATB1 (top) and β-actin (bottom) in human Treg and Tconv, and densitometric analysis to quantify ratio of SATB1 to β-actin (right). (d) SATB1 expression was determined by flow cytometry (left) in human Treg and Tconv with quantification shown in the graph at right. (e) SATB1 expression was determined by flow cytometry after stimulation of human Treg and Tconv for 2 d (left) with quantification shown normalized to resting Tconv in the graph at right. (f) Relative SATB1 mRNA expression in human iTreg, stimulated T cells (stim T) and unstimulated T cells (unstim T) on day 5. (g) SATB1 expression was determined by flow cytometry in human iTreg, stim T and unstim T (left) with quantification shown in the graph at right. (h) Cytometric bead assay for IL-4 and IFN-γ secretion in the supernatants of human iTreg, stim T and unstim T. (i) Relative Foxp3 (left) and SATB1 mRNA expression (right) in Tconv lentivirally transduced with Foxp3 vector (Foxp3 vector) or control vector (Ctrl vector) rested for 3 days. (j) Relative IL-5 (left) and IFN-γ mRNA expression (right), assessed and presented as in i. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). Numbers in plots indicate mean fluorescence intensity (d,e). Data are representative of five experiments (b,e,i,j; mean and s.d.), six experiments (c,f; mean and s.d.), three experiments (g; mean and s.d.), eleven experiments (d; mean and s.d.), or three independent experiments (h; mean ± s.d. of triplicate wells), each with cells derived from a different donor.

Transcriptome data were validated in an independent set of samples by qRT-PCR (Fig. 1b), immunoblotting (Fig. 1c), and single cell analysis by flow cytometry (Fig. 1d) clearly demonstrating reduced SATB1 expression in human Treg. As increased SATB1 expression has been previously linked to activation of pan-T cell populations29,33, we assessed the dynamics of SATB1 protein expression in Tconv and Treg during activation using T cell receptor stimulation in the presence of co-stimulation or interleukin-2 (IL-2) (Fig. 1e) as well as mitogens (data not shown). Analysis of SATB1 expression established a stimulation dependent up-regulation of SATB1 in Tconv while resting Treg had a significantly lower SATB1 expression than Tconv and this expression was only modestly up-regulated after T cell activation. Next we assessed SATB1 in induced Treg (iTreg)34. These iTreg expressed Foxp3 mRNA and protein, and showed T cell suppressive function (data not shown). Similar to natural Treg, SATB1 was not induced in iTreg under these conditions while significantly enhanced expression was observed in cells stimulated via TCR and CD28 (Fig. 1f,g). Moreover, TH1 and TH2 cytokine production was significantly abrogated in the absence of SATB1 (Fig. 1h). To determine whether Foxp3 induction in iTreg was necessary to suppress SATB1 we performed gain-of-function experiments ectopically over-expressing Foxp3 in Tconv cells. High expression of Foxp3 resulted in reduced expression of SATB1 (Fig. 1i), which was accompanied by a concomitant decrease in cytokine expression (Fig. 1j) and the induction of a Treg cell gene signature (Supplementary Fig. 2). Less abundant Foxp3 expression did not result in significant repression of SATB1 or induction of a Treg cell gene signature (data not shown). Taken together, reduced expression of SATB1 is a hallmark of both iTreg and Treg in humans and repression of SATB1 depends on sufficiently high expression of Foxp3.

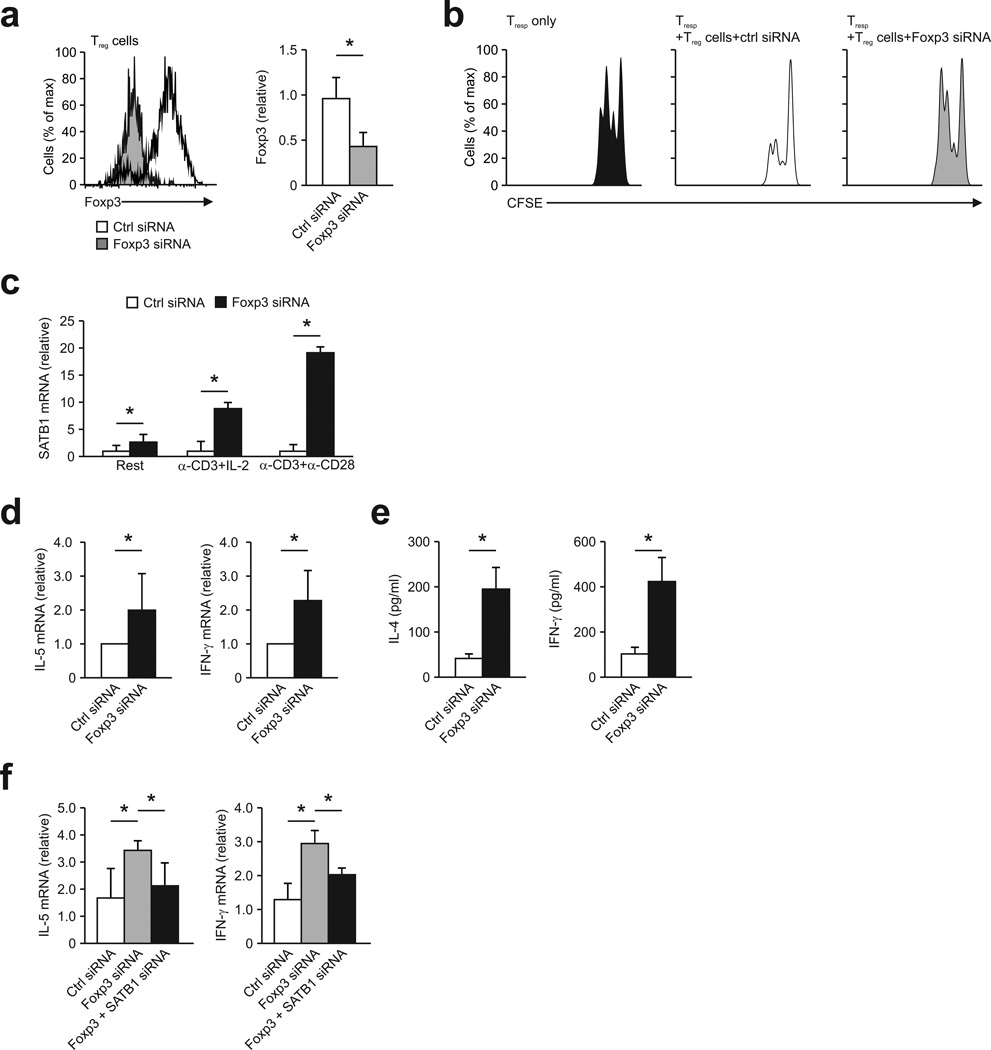

Loss of Foxp3 in Treg results in high SATB1 expression

To further assess the role of Foxp3 in SATB1 repression in human Treg we performed loss-of-function experiments. Silencing Foxp3 by siRNA resulted in loss of Foxp3 expression as well as genes associated with Treg cells (Supplementary Fig. 3) and consequently loss of suppressive function in Treg (Fig. 2a,b). A small but significant increase of SATB1 expression was evident in unstimulated Foxp3-depleted human Treg (Fig. 2c), however, this was significantly enhanced when Treg were stimulated via TCR together with co-stimulation or IL-2. This increase in SATB1 expression was associated with production of TH1 (interferon-γ; IFN-γ) and TH2 (IL-4 and IL-5) cytokines (Fig. 2d,e). As this effect could have been a direct effect of Foxp3 on the cytokine genes themselves we developed a strategy to knockdown SATB1 and Foxp3 simultaneously in human Treg cells. Additional knockdown of SATB1 in human Treg with a silenced FOXP3 gene (Supplementary Fig. 4) resulted in a significantly decreased induction of T helper cytokines (Fig. 2f) demonstrating that expression of Teff cytokines in Foxp3-deficient Treg cells is governed by SATB1. Similar results were obtained when expanded human Treg cells were transduced with lentiviruses encoding miR RNAi targeting Foxp3 and SATB1 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Together, these findings establish that Foxp3 negatively regulates SATB1 expression and that reducing SATB1 expression is required to prevent expression of Teff cytokines in human Treg, cells, thus assigning a key function of Foxp3-SATB1 interaction to the Treg phenotype.

Figure 2. Rescue of SATB1 expression after silencing of Foxp3 in Treg cells.

(a) Foxp3 expression was determined by flow cytometry (left) in human Treg transfected with siRNA targeting Foxp3 (Foxp3 siRNA) or nontargeting (control) siRNA (Ctrl siRNA) 48 h post knockdown with quantification shown in the graph at right. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). (b) Suppression of allogeneic CD4+ T cells, labeled with the cytosolic dye CFSE (responding T cells (Tresp)) by human Treg transfected with siRNA targeting Foxp3 (Foxp3 siRNA) or nontargeting (control) siRNA (Ctrl siRNA), presented as CFSE dilution in responding T cells cultured with CD3+CD28-coated beads and Treg at a ratio of 1:1 or without Treg (Tresp only). (c) Relative SATB1 mRNA expression in human Treg after silencing of Foxp3. Treg were transfected and cultivated for 48 hours without stimulation (Rest) or in the presence of CD3 and IL-2 (α-CD3+IL-2) or CD3 and CD28 (α-CD3+α-CD-28). *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). (d) Relative IL-5 (left) and IFN-γ mRNA expression (right) in siRNA-treated Treg stimulated for 48 hours in the presence CD3 and IL-2. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). (e) Cytometric bead assay for IL-4 and IFN-γ secretion in the supernatants of siRNA-treated Treg stimulated as in d. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). (f) Relative IL-5 (left) and IFN-γ mRNA expression (right) in Treg transfected with nontargeting (control) siRNA (Ctrl siRNA), Foxp3-targeting siRNA (Foxp3 siRNA) or Foxp3- and SATB1-targeting siRNA (Foxp3 + SATB1 siRNA) followed by stimulation with CD3+CD28-coated beads for 48 hours. *P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA with LSD). Data are representative of six experiments (a,c; mean and s.d.), four experiments (d,f; mean and s.d.), three independent experiments (b), or three independent experiments (e; mean ± s.d. of triplicate wells), each with cells derived from a different donor.

Foxp3 is not suppressed by SATB1 in Tconv cells

To exclude the possibility that SATB1 may reciprocally repress FOXP3 in Tconv cells we performed siRNA-mediated knockdown of SATB1 in human naïve Tconv cells to assess whether SATB1 down-regulation in Tconv cells might allow for elevated Foxp3 expression and a conversion of Tconv into Treg cells (Supplementary Fig. 6a). We did not observe increased Foxp3 expression in resting and stimulated naïve Tconv after silencing of SATB1, including iTreg-inducing conditions (Supplementary Fig. 6b). These results suggest that higher SATB1 abundance is not necessary for low expression of Foxp3 in resting Tconv cells and that Foxp3 induction in naïve Tconv cells following stimulation occurs independently of SATB1. In line with this finding, we did not observe increased induction of several Treg cell associated genes after knockdown of SATB1 (Supplementary Fig. 6c).

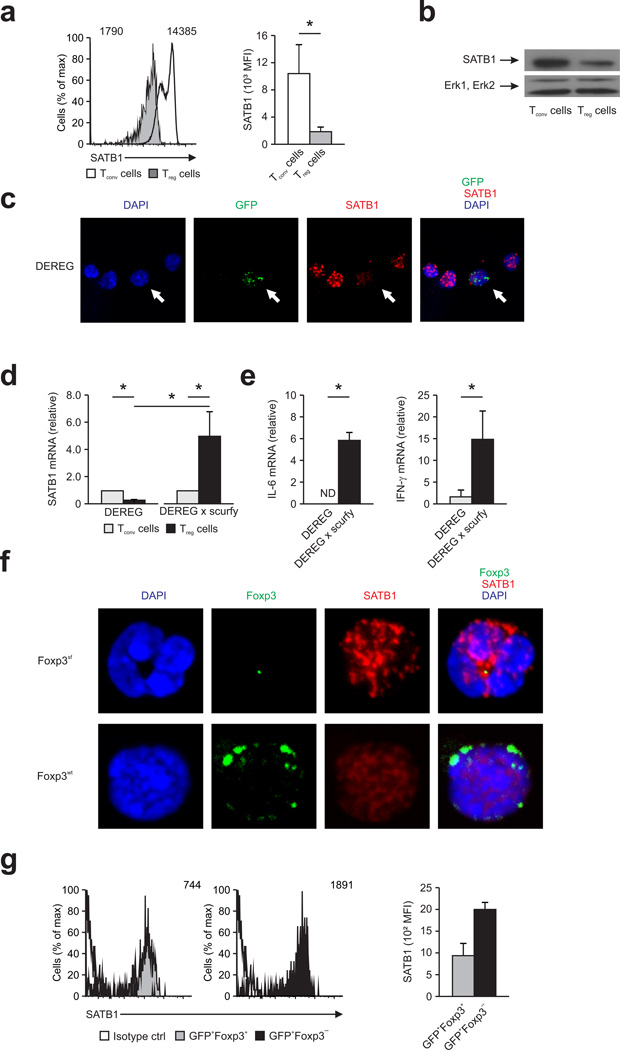

SATB1 expression in mouse Treg cells

To address whether SATB1 regulation is conserved between human and murine Treg we analyzed SATB1 expression by qPCR, immunoblotting, flow cytometry and confocal microscopy in T cells derived from two different Foxp3 reporter mice (DEREG35, Foxp3-GFP-Cre21). Similar to human Treg cells, SATB1 mRNA and protein expression was lower in mouse Treg compared with Tconv cells isolated from thymus, spleen or lymph nodes (Fig. 3a–c, and data not shown). SATB1 expression in CD4+ single-positive thymocytes was considerably higher than in peripheral CD4+ Tconv cells from the spleen or lymph nodes (data not shown), which further supports the essential role of SATB1 during early thymocyte development as established in complete Satb1−/− mice25. Despite this, thymic Foxp3+ Treg still displayed a significant down-regulation of SATB1 compared with Foxp3− cells.

Figure 3. Foxp3-dependent repression of SATB1 expression in mouse Treg cells.

(a) SATB1 expression was determined by flow cytometry (left) in freshly isolated Treg and Tconv from spleen of male DEREG mice with quantification shown in the graph at right. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). (b) Immunoblotting for SATB1 (top) and Erk1, Erk2 (bottom) in mouse Treg and Tconv. (c) Z-projection of immunofluorescence for SATB1 (red) and GFP (green) in thymocytes from male DEREG mice; nuclei are stained with the DNA-intercalating dye DAPI. White arrow depicts Treg. (d) Relative SATB1 mRNA expression in CD4+GFP+ (Treg) and CD4+GFP− (Tconv) T cells from male DEREG or Foxp3-deficient DEREG × scurfy mice. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). (e) Relative IL-6 (left) and IFN-γ mRNA expression (right) in CD4+GFP+ Treg derived from male DEREG or Foxp3-deficient DEREG × scurfy mice. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). (f) Confocal microscopy for SATB1 (red) and Foxp3 (green) in thymic Treg from female DEREG mice heterozygous for the scurfy mutation counterstained with DAPI (blue). CD4+GFP+FOXP3− Foxp3-deficient Treg (top, Foxp3sf) or CD4+GFP+FOXP3+ Foxp3-competent Treg (bottom, Foxp3wt). (g) SATB1 expression was determined by flow cytometry (left) in thymic single positive CD4+GFP+FOXP3+ (left, grey) and CD4+GFP+FOXP3− Treg (right, black) from female DEREG mice heterozygous for the scurfy mutation with quantification shown in the graph at right. Isotype control shown as solid line. Numbers in plots indicate mean fluorescence intensity (a,g). Data are representative of three independent experiments (a; mean and s.d.), two independent experiments (g; mean and s.d.), two independent experiments (c,f,b), or two independent experiments (d,e; mean ± s.d. of triplicate wells).

To establish Satb1 as a Foxp3 target gene we analyzed Treg from male DEREG mice harboring a spontaneously mutated Foxp3 allele (DEREG x scurfy). Flow-sorted Treg from these animals displayed a significantly increased SATB1 expression in Treg compared to Foxp3-competent Treg (Fig. 3d). In line with this finding an increase of TH1 and TH2 cytokines in vivo was observed in Treg from DEREG x scurfy mice (Fig. 3e). SATB1 mRNA expression in Treg versus Tconv cells was further validated by reassessment of three transcriptome data sets (GSE18387, GSE6681, GSE11775)5,36,37 derived from mice with a mutated Foxp3 gene in Treg (data not shown).

Female heterozygous DEREG x scurfy mice harbor both Foxp3-competent and Foxp3-incompetent Treg cells. Side-by-side comparison of Foxp3-competent and Foxp3-incompetent Treg cells by immunofluorescence revealed a cell-intrinsic function of Foxp3 in repressing SATB1 (Fig. 3f). Similar to previous reports we observed nuclear localization of SATB1 in Foxp3− thymocytes forming a cage-like structure within the nucleus (Fig. 3c)26. Increased SATB1 signals in Foxp3-incompetent Treg cells with unchanged localization and distribution further support that SATB1 expression is regulated by Foxp3 (Fig. 3f). Upregulation of SATB1 in Foxp3sf GFP+ Treg was further quantified by intracellular flow cytometry (Fig. 3g). Overall, these data clearly establish increased SATB1 mRNA and protein expression as a consequence of Foxp3 deficiency in Treg.

Foxp3 binds to the SATB1 locus in human Treg cells

Inverse correlation between Foxp3 and SATB1 expression in murine and human Treg strongly suggested that Foxp3 might act directly as a transcriptional repressor of the SATB1 locus. We performed Foxp3-ChIP tiling arrays and promoter arrays using chromatin isolated from human natural Treg cells (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 7a) as well as bioinformatic in silico prediction to identify 16 regions for qPCR validation. Binding regions identified were located upstream of the transcriptional start site as well as in the genomic locus of SATB1 (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 2). Foxp3 binding within the promoter region or genomic locus of SATB1 in Treg was demonstrated by ChIP-coupled quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR) (Fig. 4c) and electrophoretic mobility-shift assays (data not shown) clearly demonstrating binding to the SATB1 locus similar to known targets of Foxp3 (Supplementary Fig. 7b–f). To probe functional consequences of Foxp3 binding to the SATB1 locus, we performed luciferase reporter assays for six of the Foxp3 binding regions. Foxp3 binding regions were cloned in between a minP promoter element and a luciferase reporter gene38. Co-transfection of these reporter-constructs with a human FOXP3 expression vector led to a significant decrease in activity for four of these regions with more than one Foxp3 binding motif (Fig. 4d). Mutation of predicted Foxp3 binding motifs within these regions rescued luciferase activity (Fig. 4d) indicating that SATB1 expression is actively repressed by Foxp3 binding to several regions within the genomic SATB1 locus. Further support for Foxp3 binding was derived from in vitro DNA-protein interaction analysis using recombinant Foxp3 protein with either wild-type or mutated Foxp3 binding motifs within the FOXP3-binding regions BR9 and BR10 demonstrating strong binding of Foxp3 only to the wild-type sequences whereas the mutated motifs showed almost no interaction with Foxp3 (Fig. 4e). Taken together, these data establish Foxp3 as an important repressor directly binding to the SATB1 locus in Treg cells and preventing SATB1 transcription. .

Figure 4. Direct suppression of SATB1 transcription by Foxp3.

(a) Foxp3 ChIP tiling array data (blue) from human expanded cord-blood Treg. Data were analyzed with MAT and overlayed to the SATB1 locus to identify binding regions (1–13, p < 10−5 and FDR < 0.5%). Data are representative of two independent experiments with cells derived from different donors. (b) Schematic representation of Foxp3 binding regions (BR) at the human genomic SATB1 locus identified by in silico prediction within the regions identified in a. (c) ChIP analysis of human expanded cord-blood Treg cells with a Foxp3-specific antibody and PCR primers specific for Foxp3 binding regions. Relative enrichment of Foxp3 ChIP over input normalized to IgG was calculated. A region −15 kb upstream (−15kb) was used as a negative control. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). Data are representative of three independent experiments (mean and s.d.) with cells derived from different donors. (d) Luciferase assay of FOXP3 binding to the respective binding regions at the SATB1 locus in HEK293T cells, transfected with luciferase constructs containing wild-type (WT) or mutated (Mut) binding regions BR9–14 of the SATB1 locus (with mutation of the Foxp3-binding motifs), together with a FOXP3 encoding expression vector or control vector (Ctrl). *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). Data is from one representative experiment of two (mean and s.d. of triplicate wells). Numbers indicate Foxp3-binding motifs within each region. (e) Determination of the KD-values of Foxp3 binding to a wild-type (WT) or mutated (Mut) Foxp3 binding motif in BR9 and BR10 at the SATB1 locus by filter retention analysis. Data are representative of three independent experiments (mean and s.d. of triplicates).

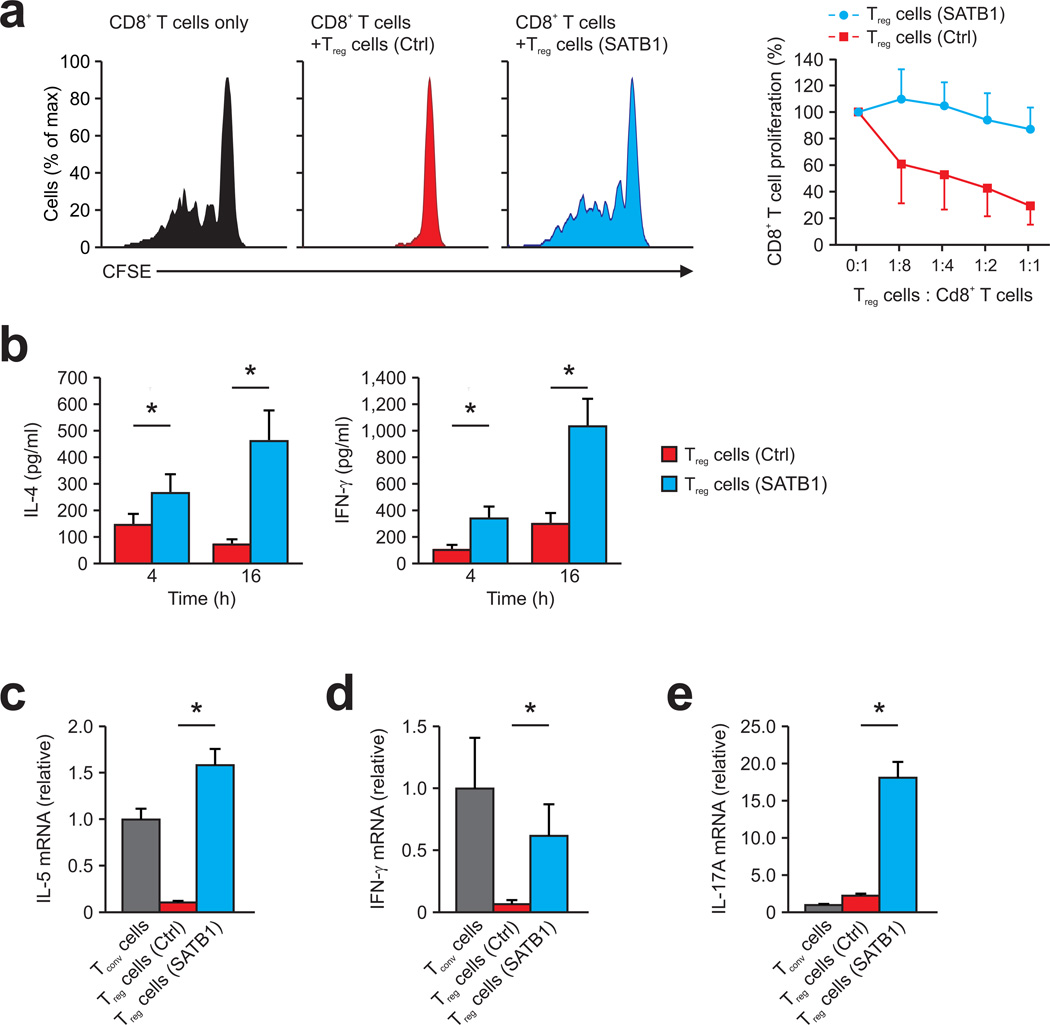

Ectopic SATB1 reprograms human Treg to Teff in vitro

To determine whether reduced SATB1 expression is required for Treg to exert regulatory function we overexpressed SATB1 in human natural CD4+CD25hi Foxp3+ Treg cells using a lentiviral vector carrying the SATB1 full-length transcript (Supplementary Fig. 8). Human Treg or Tconv were stimulated for 24 h with CD3 and CD28-coated beads in the presence of IL-2. After stimulation, Treg cells were lentivirally transduced with pELNS DsRED 2A SATB1 which expresses DsRED at a ratio of 1:1 to the transgene39 or control virus containing only DsRED. Cells were expanded prior to sorting DsRED-positive cells. Only SATB1- and control-transduced cells showing highly similar Foxp3 and DsRED expression were used for further analysis (Supplementary Fig. 8a). In sharp contrast to control-transduced Treg, SATB1 over-expressing Foxp3+ Treg cells lost their suppressive function (Supplementary Fig. 8b,c and Fig. 5a). At the same time, these cells gained expression of TH1 (IFN-γ), TH2 (IL-4) and TH17 (IL-17A) cytokines (Fig. 5b–e) suggesting a reprogramming of Treg cells into Teff in the presence of abundant SATB1 despite similar Foxp3 expression. As expected, Tconv cells transduced with SATB1 using the same approach had no suppressive function (Supplementary Fig. 9). These data strongly support that ectopic expression of SATB1 in Treg is sufficient to convert the Foxp3-mediated program into Teff programs.

Figure 5. SATB1 expression in human Treg reprograms Treg into effector T cells.

(a) Suppression of CD8+ T cells, labeled with the cytosolic dye CFSE (CD8+ T cells) by human Treg lentivirally transduced with SATB1 (Treg cells (SATB1), blue) or control vector (Treg cells (Ctrl), red), presented as CFSE dilution in responding T cells cultured with CD3-coated beads and Treg at a ratio of 1:1 or without Treg (CD8+ T cells only; left), and as percent proliferating CD8+ T cells versus the Treg cell/CD8+ T cell ratio (right). Data are representative of three independent experiments (mean and s.d.) with cells derived from different donors. (b) Cytometric bead assay for IL-4 and IFN-γ secretion in the supernatants of human Treg lentivirally transduced with SATB1 (Treg cells (SATB1), blue) or control vector (Treg cells (Ctrl), red) assessed 4 and 16 h after stimulation with CD3+CD28-coated beads. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). Data is from one representative experiment of two (mean and s.d. of triplicate wells) with cells derived from different donors. (c–e) Relative IL-5 (c), IFN-γ (d), and IL-17A (e) mRNA expression (right) in human Tconv (grey) and Treg lentivirally transduced with SATB1 (Treg cells (SATB1), blue) or control vector (Treg cells (Ctrl), red) activated for 16 h with CD3+CD28-coated beads. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). Data is from one representative experiment of two (mean and s.d. of triplicate wells) with cells derived from different donors.

High SATB1 expression induces transcriptional Teff programs

To estimate the genome-wide reprogramming in SATB1 over-expressing Treg cells whole transcriptome analysis was performed. Using stringent filter criteria a total of 100 genes were found to be significantly increased in SATB1-expressing Treg cells whereas 21 were decreased (Fig. 6a). Analysis of the differentially expressed genes revealed that 20% were associated with elevated expression in Tconv (in comparison to Treg), 29% of the changed genes were primarily linked with T cell activation, and 16% were classified as common T cell genes. The remaining genes (35%) showed no known association with T cell function or lineage and were classified as SATB1-induced (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, compiling gene lists previously associated with TH1, TH2 and TH17 differentiation revealed induction of many genes involved in Teff differentiation in SATB1-expressing Treg cells (Fig. 6c). In contrast genes representing the human Treg cell gene signature were unchanged in SATB1-expressing Treg cells (Fig. 6d). Since we used polyclonal human Treg cells for this analysis, it is not surprising that we find the three major T cell differentiation programs simultaneously. In summary, low SATB1 expression in Treg is necessary to permit suppressive function and to ensure inhibition of effector cell differentiation of regulatory T cells.

Figure 6. Transcriptional Teff programs are induced in SATB1 expressing Treg.

(a) Microarray analysis of human Treg lentivirally transduced with SATB1 (SATB1) or control vector (Ctrl) after 16 hours stimulation with CD3+CD28-coated beads, presented as a heat map of differentially expressed genes. Data were z-score normalized. (b) Cross annotation analysis using 4 classes: genes associated with Tconv but not Treg cells (Tconv cell-dependent, yellow), with T cell activation (activation-dependent, green), common T-cell genes (common, orange), and SATB1-induced genes (SATB1-induced, black). Numbers indicate genes within each group. (c) Visualization of gene expression levels of genes previously associated with TH1, TH2, or TH17 differentiation, presented as a heat map. Data were z-score normalized. P values for TH associated genes determined by χ2 test in comparison to the complete data set (TH specific gene enrichment): TH1, P = 3.24×10−6; TH2, P = 9.03×10−15; TH17, P = 1.16×10−6. (d) Changes in genes associated with the human Treg signature as assessed in Treg lentivirally transduced with SATB1 (SATB1) in comparison to control vector (Ctrl). The mean log2 fold-changes of the comparison Treg to Tconv (red dots) and SATB1 to control-transduced Treg (blue dots) were plotted and both comparisons were ranked by fold change in the Treg vs. Tconv comparison. Data are derived from three independent experiments with cells derived from different donors.

Epigenetic regulation of SATB1 transcription in Treg cells

The strong dependency of Treg function on the repression of SATB1 implies the involvement of additional regulatory mechanisms. When assessing DNA methylation, we identified three CpG-rich sites upstream of exon 1 at the SATB1 locus (Supplementary Fig. 10). However, in contrast to the FOXP3 locus itself (Supplementary Fig. 10a)22, the SATB1 locus was similarly demethylated in Treg and Tconv cells (Supplementary Fig. 10b), suggesting that DNA-methylation does not play a regulatory role at the SATB1 locus in Treg cells.

Next, we examined the chromatin status of the SATB1 locus by analyzing permissive and repressive histone modifications. ChIP-qPCR of expanded human Treg showed a reduction in permissive histone H3 trimethylation at Lys 4 (H3K4me3, Supplementary Fig. 11a) and increased repressive histone H3 trimethylation at Lys27 (H3K27me3, Supplementary Fig. 11b) in human Treg cells compared to Tconv cells as well as lower acetylation of histone H4 (H4Ac, Supplementary Fig. 11c). When assessing a publicly available dataset for murine Treg cells40 we could establish similar histone marks at the Satb1 locus (Supplementary Fig. 12), suggesting that a conserved regulatory circuit exists that contributes to the lower expression of SATB1 in Treg by inducing repressive epigenetic marks at the SATB1 locus.

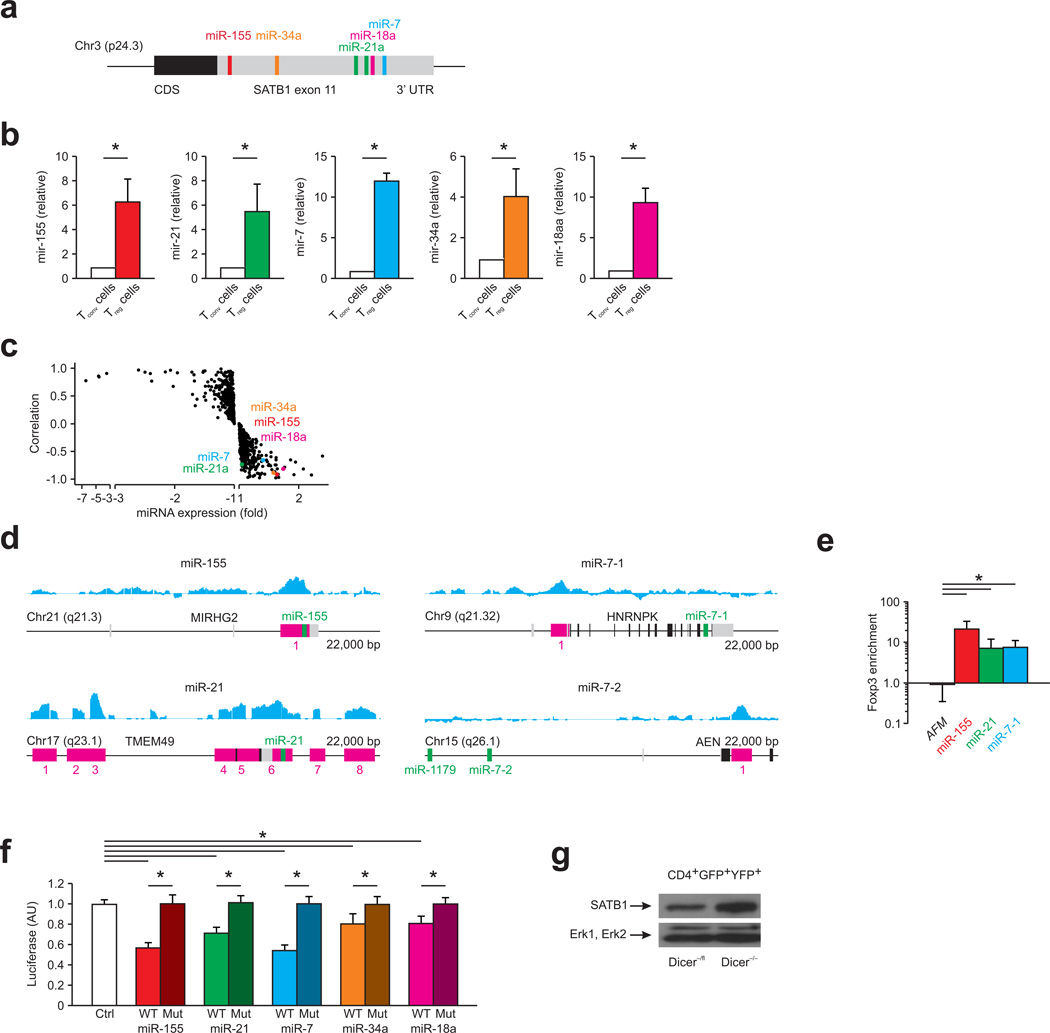

MicroRNAs regulate SATB1 in Treg cells

A prominent layer of post-transcriptional gene regulation is exerted by miRNAs. MiRNA profiling in human Treg versus Tconv cells allowed us to identify several differentially expressed miRNAs in Treg cells (data not shown). Using inverse correlation analysis between SATB1 and miRNA expression as well as computational prediction of miRNA binding of seed-matched sites (Fig. 7a), we identified 5 miRNAs that were differentially expressed between Treg and Tconv cells (Fig. 7b) and showed a significant inverse correlation between SATB1 and miRNA expression (Fig. 7c). Of these 5 miRNAs, miR-155, miR-21, and miR-7 are direct targets of Foxp3 as previously reported for miR-155 (refs. 31,41,42) and miR-21 (ref. 43) and confirmed by Foxp3-ChIP tiling arrays and ChIP-qPCR (Fig. 7d,e and Supplementary Fig. 13) as well as functional analysis (S. Barry, unpublished data). Assessment of miRNA expression in Foxp3-overexpressing Tconv cells and Foxp3-silenced Treg cells confirmed these miRNAs as targets of Foxp3 (Supplementary Fig. 14). For the assessment of functionally relevant binding of the miRNAs to the 3′ UTR of the SATB1 mRNA we fused the SATB1 3′ UTR to a luciferase reporter gene and determined luciferase activity in cells transfected with synthetic miRNAs. Expression of any of the 5 miRNAs significantly repressed constitutive luciferase activity with the 3 miRNAs that are direct targets of Foxp3 clearly showing the strongest effect (Fig. 7f). Mutation of the respective binding motifs resulted in restoration of luciferase activity (Fig. 7f). As exemplified for miR-155, loss of function of a single miRNA only resulted in minor differences in SATB1 mRNA expression in primary human Treg (Supplementary Fig. 15a) indicating that the loss of a single miRNA may be incapable of rescuing SATB1 expression. Complete loss of all miRNAs, however, as achieved in mice by a Treg-specific deletion of Dicer1 (ref. 21) clearly lead to up-regulation of SATB1 at both mRNA and protein level (Fig. 7g and Supplementary Fig. 15b). These results suggest that Foxp3 is able to confer Treg-specific down-regulation of SATB1 expression not only by direct binding to the Satb1 locus but also using a second layer of regulation using miRNAs.

Figure 7. SATB1 expression is repressed by miRNA in Treg.

(a) Representation of the human genomic SATB1 3′ UTR and the conserved miRNA binding sites. (b) Relative miR-155, miR-21, miR-7, miR-34a, and miR-18a expression human Treg and Tconv. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). Data are representative of five experiments (mean and s.d.) with cells derived from different donors. (c) Correlation of miRNA expression with SATB1 mRNA expression is plotted against miRNA fold change (Treg vs. Tconv) for all 735 miRNA assessed by microarrays. Highlighted are miR-155, miR-21, miR-7, miR-34a, and miR-18a. Data are representative of three experiments with cells derived from different donors. (d) Foxp3 ChIP tiling array data (blue) for miR-155, miR-21, and miR-7 from human expanded cord-blood Treg. Data were analyzed with MAT and overlayed to the respective locus to identify binding regions (P < 10−5 and FDR < 0.5%). Data are representative of two independent experiments with cells derived from different donors. (e) ChIP analysis of human expanded cord-blood Treg cells with a Foxp3-specific antibody and PCR primers specific for miR-155, miR-21, and miR-7. Relative enrichment of Foxp3 ChIP over input normalized to IgG was calculated. The AFM locus was used as a negative control. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). Data are representative of three independent experiments (mean and s.d.) with cells derived from different donors. (f) Dual-luciferase assay of HEK-293T cells transfected with luciferase constructs containing wild-type (WT) 3′ UTR or mutated (Mut) 3′ UTR of SATB1 (with mutation of the miRNA-responsive elements), together with synthetic mature miRNAs or a synthetic control miRNA (Ctrl). *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). Data are representative of three independent experiments (mean and s.d.). (g) Immunoblotting for SATB1 (top) and Erk1, Erk2 (bottom) in Treg from mice with a Treg-specific complete DICER loss (Dicer1fl/fl) in comparison to Dicer1+/fl Treg. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Abundant SATB1 expression decreases Treg function in vivo

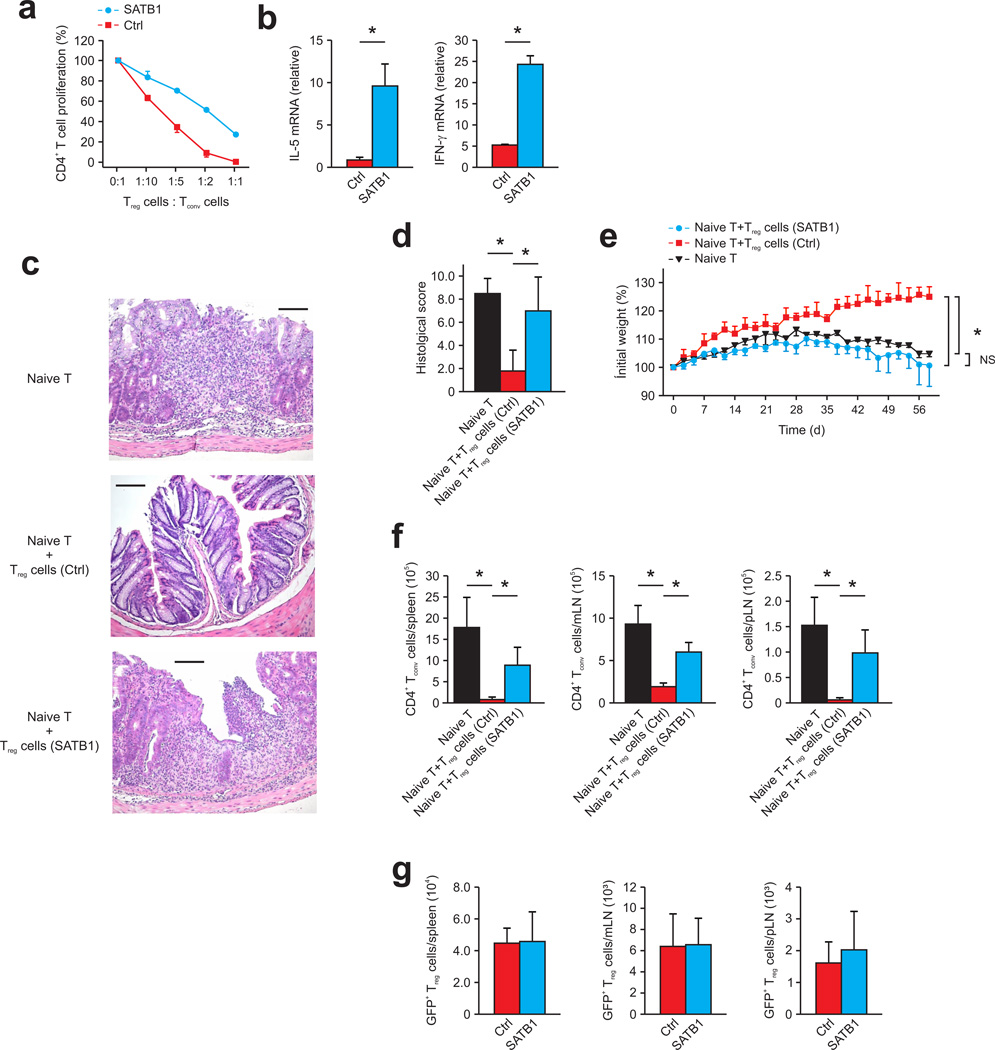

To assess whether SATB1 expression results in reduced regulatory function in mouse Treg in vitro and in vivo we overexpressed SATB1 in mouse CD4+ Foxp3+ Treg cells from DEREG mice using a lentivirus encoding the Satb1 full-length transcript (Supplementary Fig. 16). Sorted CD4+ Foxp3+ Treg cells from DEREG mice were expanded for 10–14 days with CD3 and CD28-coated beads in the presence of IL-2. After this initial expansion period, expanded Treg cells were transduced with a SATB1-IRES-Thy1.1 or control lentivirus. Cells were expanded for 4 additional days in the presence of CD3 and CD28-coated beads and IL-2 prior to sorting Thy1.1-positive GFP+ Treg. SATB1 and control-transduced Treg had similar Foxp3 expression (Supplementary Fig. 16a). In contrast to control-transduced Treg cells, the overexpression of SATB1 in Foxp3+ Treg cells resulted in a loss of suppressive function and acquisition of TH1 (IFN-γ) and TH2 (IL-5) effector cytokine expression (Fig. 8a,b and Supplementary Fig. 16b–f) supporting a reprogramming of Treg cells into Teff cells in the presence of significantly elevated SATB1 expression.

Figure 8. Ectopic expression of SATB1 in Treg results in reduced suppressive function in vivo.

(a) Suppression of CD4+ T cells, labeled with the cytosolic dye eFluor 670 (Tconv cells) cultured with CD3+CD28-coated beads by expanded mouse Treg lentivirally transduced with SATB1 (SATB1, blue) or control vector (Ctrl, red), presented as percent proliferating Tconv cells versus the Treg cell/Tconv cell ratio (right). (b) Relative IL-5 (left) and IFN-γ mRNA expression (right) in murine Treg lentivirally transduced with SATB1 (SATB1, blue) or control vector (Ctrl, red). (c) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of colon sections from Rag2−/− mice at 9 weeks after the transfer of CD4+CD45RBhi naive T cells (naïve T) alone or in combination with control-transduced Treg (Treg cells (Ctrl)) or SATB1-transduced Treg (Treg cells (SATB1)). Original magnification, ×200; scale bars, 100 µm. (d) Histology scores of colon sections of Rag2−/− mice at 9 weeks after the transfer in c. (e) Body weight of Rag2−/− mice at 9 weeks after the transfer in c, presented relative to initial body weight. (f,g) Recovery of Tconv (f) and Treg (g) from spleens, mesenteric, and peripheral lymph nodes of Rag2−/− mice at 9 weeks after the transfer in c. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). NS, not significant. Data are representative of three independent experiments (b; mean and s.d.), two independent experiments (a; mean and s.e.m. of triplicate cultures), or are pooled from two independent experiments (c–g; mean and s.d. of four resp. five recipient mice).

To assess in vivo suppressor capacity of the manipulated Treg cells, control Treg or Treg cells overexpressing SATB1 were transferred together with naïve CD4+CD45RBhi T cells (isolated from normal mice) into Rag2−/− recipient mice. Transfer of naïve CD4+CD45RBhi T cells alone led to the development of colitis (Fig. 8c–e). As expected, Rag2−/− mice that received naïve CD4+CD45RBhi T cells and control-transduced Treg cells did not show colitis-associated pathology (Fig. 8c–e) while mice receiving only naïve CD4+CD45RBhi cells had colonic infiltrates and weight loss. Transfer of SATB1-overexpressing Treg cells together with naïve CD4+CD45RBhi T cells resulted in colitis-associated pathology suggesting an impairment in suppressor function of SATB1-overexpressing Treg cells concomitant with a gain of effector function (Fig. 8c–e). We observed a significant expansion in the number of Tconv cells in mice receiving either no Treg cells or SATB1-overexpressing Treg cells in spleen, mesenteric and peripheral lymph nodes (Fig. 8f), while the number of cells that maintained Foxp3 expression in spleen, mesenteric and peripheral lymph nodes was equal in mice receiving control vector-transduced or SATB1-overexpressing Treg cells (Fig. 8g). Thus, Foxp3+ Treg cells expressing elevated amounts of SATB1 show lower suppressor function with a concomitant gain of Teff programs in vivo and in vitro suggesting that down-regulation of SATB1 in Treg cells is necessary to maintain a stable suppressive phenotype (Supplementary Fig. 17).

DISCUSSION

In Treg numerous mechanisms have been implicated in their suppressive function upon contact to other immune effector cells1. At the same time intrinsic inhibition of Teff function mainly by FOXP3-induced mechanisms seems to be necessary for Treg to exert suppressive function. In this report we identified the repression of SATB1 in Treg to be required for suppressive function and inhibition of effector differentiation of these cells. As up-regulation of SATB1 is required for the induction of Teff cytokines in Tconv the profound lack of up-regulation of SATB1 following stimulation in Treg suggests that FOXP3-mediated suppression of SATB1 plays an important role in inhibiting cytokine production within a Treg. In support of this, ectopic expression of high levels of SATB1 in Treg led to the induction of Teff cytokines and loss of suppressive function despite the expression of FOXP3 in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, SATB1 expression is controlled directly by FOXP3-mediated transcriptional repression, histone modifications as well as the induction of miRNAs binding to the 3’UTR of SATB1. Together these findings establish that continuous active repression of central mechanisms involved in Teff programs provided by SATB1 is necessary for Treg to exert their suppressive function.

Thus a major finding of our study is that Treg not only depend on the induction of FOXP3-mediated genes associated with suppressive function but also on the specific repression of molecules such as SATB1 to prevent Teff function. SATB1 expression at low levels seems to be necessary to retain functional T-cell integrity not only in Tconv but also in Treg as complete SATB1 KO are basically devoid of T cells in the periphery25. While FOXP3 clearly dictates the repression of SATB1 in Treg thereby preventing Teff function, we have no evidence so far for an inverse control of FOXP3 by SATB1 in Tconv, which together favors a model with Teff programs continually and actively overruled by FOXP3-mediated transcriptional repression within a Treg.

Further evidence for such a model comes from studies elucidating the effect of the transcriptional repressor Eos in Treg13. Eos directly interacts with FOXP3 to specifically induce chromatin modifications that result in gene silencing, while genes induced by FOXP3 were not affected. Interestingly, loss of Eos abrogated suppressive Treg function but only partially endowed Treg with Teff functions consistent with the normal repression of Teff differentiation within a Treg. Similarly, loss of Runx1-CBFβ heterodimers, another component of the FOXP3 containing multi-protein complex, in Treg leads to reduction of FOXP3 expression, loss of suppressor function and gain of IL-4 expression by Treg44,45. FOXP3 as well as Eos and Runx1-CBFβ heterodimers have been shown to directly repress certain effector cytokines such as IFN-γ or IL-4 suggesting Treg may use multiple mechanisms to suppress Teff programs13,18,44. Nevertheless, the ectopic expression of SATB1 in Treg was sufficient to induce effector cytokines suggesting that high levels of SATB1 can overcome FOXP3 repression of downstream targets. This might be similarly true in activated Tconv that can express lower levels of FOXP3 temporarily during early activation phases.

Recently the FOXO transcription factors Foxo1 and Foxo3 have also been implicated in the inhibition of Teff function in Treg14. Interestingly, lack of Foxo1 and Foxo3 in Treg is sufficient to induce TH1 and TH17 effector cytokines but not TH2 cytokines whereas SATB1 seems to have a more profound effect on TH2 cytokines under certain conditions29,46. Together these findings point to a hierarchy of repressive mechanisms ensuring suppression of Teff function in Treg.

Our findings support a model of continuously active regulatory networks shaping the overall function of T cells in the periphery as an alternative to terminal differentiation. An active and continuous blockade of Teff function instead of terminal Treg differentiation allows T cells a higher degree of functional plasticity e.g. under inflammatory conditions where Treg can gain effector function once FOXP3 is switched off24,47–49.

ONLINE METHODS

Mice

DEREG, scurfy, DEREG × scurfy, Foxp3-GFP-hCre BAC × Dicer1fl/fl, and Foxp3-GFP-hCre BAC × Dicer1fl/fl × ROSA26R-YFP mice were previously described4,21,35,50.

All animal experiments were approved by the responsible Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (University of California, San Francisco, Lower Saxony, Germany or North Rhine Westfalia, Germany).

Antibodies and flow cytometry analysis

Fluorescent-dye-conjugated antibodies were purchased from Becton Dickinson, BioLegend, or eBioscience. Alexa 647-conjugated mouse anti-human SATB1 monoclonal antibody (clone 14) cross-reactive to mouse SATB1 was prepared by R. Balderas (BD Biosciences). Intracellular staining of human and murine Foxp3 and SATB1 was conducted using either the human or mouse Foxp3 Regulatory T-cell Staining Kit (BioLegend).

Purification and sorting of human Treg cells

Human Treg and Teff cells were purified from whole blood of healthy human donors in compliance with institutional review board protocols (Ethics committee of the University of Bonn) by negative selection using CD4-RosetteSep (Stem Cell), followed by positive-selection using CD25-specific MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotech) or sorting on a FACSDiVa or Aria III cell sorter (Becton Dickinson) after incubating cells with combinations of fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibodies to CD4, CD25, and CD127.

qRT–PCR

Total RNA extracted using TRIZOL (Invitrogen) was used to generate cDNA along with the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Roche Diagnostics). qRT–PCR was performed using the LightCycler Taqman master kit and the Universal Probe Library assay on a LightCycler 480 II (Roche Diagnostics). Results were normalized to housekeeping gene expression.

Immunoblot analysis

Cell lysates from purified cells were prepared as previously described51 followed by immunoblotting with SATB1 antibody (BD, clone 14) as well as human beta-actin (Millipore, C4) or murine Erk1, Erk2 antibody (Cell signaling, L34F12) as loading control.

Whole-genome gene expression in human cells

All RNA was extracted using TRIZOL (Invitrogen) and purified in our laboratory using standard methods. Sample amplification, labeling and hybridization on Illumina WG6 Sentrix BeadChips V1 or V3 were performed for all arrays according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina). All data analyses were performed by using Bioconductor for the statistical software R (http://www.r-project.org).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Unpurified lymphocytes from male DEREG or CD4+ GFP+ Treg cells from female heterozygous DEREG × scurfy mice purified from thymus were fixed in cold paraformaldehyde for 10 min, washed with PBS, permeabilized with Triton-X and pre-blocked in PBS containing 10% normal goat serum and 1% gelatine from cold water fish skin for 30 min. Slides were then incubated in combinations of primary antibodies (rabbit anti-GFP (Invitrogen), mouse anti-Foxp3 (eBioscience, eBio7979), mouse anti-SATB1-AF647 (BD Biosciences, clone 14)) for 60 min, washed twice, and incubated with secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit-AF488, anti-mouse-AF555, Invitrogen) for 60 min, stained with DAPI and fluorescence was examined using an Olympus FluoView FV1000 or Zeiss LSM 5 LIVE confocal microscope.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation, whole genome arrays, and ChIP qPCR

Expanded human cord blood Treg cells were cultured overnight before stimulation with Ionomycin before cross-linking for 10 min in 1% formaldehyde solution. Cell lysis, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), DNA isolation steps, as well as data acquisition and analysis for human Foxp3 ChIP-on-chip experiments were carried out as previously described52.

Validation of Foxp3 binding to genomic regions was carried out by ChIP-qPCR. Reactions were performed using a RT2 SYBRgreen/ROX qPCR master mix (SABiosciences). The relative enrichment of target regions in Foxp3 immunoprecipitated material relative to input chromatin analysis was carried out using the 2−ΔΔCT method. Immunoprecipitations using rabbit IgG were used to normalize for non-specific background.

Gene-specific mRNA silencing, miRNA knockdown and agonistic miRNA

All siRNAs as well as the miRNA mimics and inhibitors were purchased from Biomers or Dharmacon. miRNA mimics were designed according to the sequences published in miRBase and resembling the double-stranded Dicer-cleavage products. miRNA-inhibitors were designed as single-stranded antisense 2′OM oligonucleotides. These were used for transfection of freshly isolated primary human Treg cells with nucleofection. For luciferase assays, HEK293T cells were transfected with both the reporter plasmids and the small RNA duplexes using Lipofectamine 2000 in a 96-well format and luciferase activity was measured 24 h later.

miRNA profiling and miRNA qRT–PCR

All RNA were extracted using TRIZOL (Invitrogen) and purified using standard methods. Sample amplification, labeling and hybridization on Illumina miRNA array matrix were performed with the human v1 MicroRNA Expression Profiling kit for all arrays in this study according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina) using an Illumina BeadStation. All data analyses were performed by using Bioconductor for the statistical software R (http://www.r-project.org). For miRNA-specific qRT-PCR, total RNA was extracted using TRIZOL. First strand complementary DNA for each miRNA assessed was synthesized by using the TaqMan MicroRNA RT kit and the corresponding miRNA specific kit (Applied Biosystems). Abundance of miRNA was measured by qPCR using the TaqMan Universal PCR MasterMix (Applied Biosystems) on a LighCycler 480 II (Roche Diagnostics). Ubiquitously expressed U6 small nuclear RNA or miR-26b were used for normalization.

Cloning of SATB1 3′UTR constructs

The SATB1 3′UTR was amplified by PCR using human genomic DNA as source material. The full-length 3′UTR construct was amplified with primers covering the full 1.2 kB region. After digestion with Xho I and NotI the fragment was cloned into the psiCHECK II vector (Promega) to generate psiCHECK II–SATB1–3′UTR.

A mutated construct was generated with PCR-based mutagenesis or the QuikChange Lightning Multi Site-Directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) following the manufacturer’s conditions.

Cloning of SATB1 constructs with potential Foxp3 binding regions

The corresponding SATB1 genomic regions were amplified by PCR using human genomic DNA as source material. After digestion the fragments were cloned into the pGL4.24 vector with a minP element upstream of the potential binding motif and a destabilized downstream Firefly luciferase.

Mutated constructs were generated with either PCR-based mutagenesis or the QuikChange Lightning Multi Site-Directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) following manufacturer’s conditions.

Luciferase assays

To assess regulation of SATB1 expression by binding of miRNA to the 3′UTR of SATB1, constructs were transfected into HEK293T cells in 96-well plates together with miRNA mimics for either miR-155, miR-7, miR-21, miR-34a, miR-18a or a scrambled control miRNA.

To assess regulation of SATB1 expression by binding of Foxp3 to the genomic locus of SATB1, constructs were transfected separately into HEK293T cells in 96-well plates together with control plasmid or plasmids expressing Foxp3 as well as a plasmid encoding renilla luciferase for normalization.

Lysis and analysis were performed 24 h post-transfection using the Promega Dual Luciferase Kit. Luciferase activity was counted in a Mithras plate reader (Berthold).

Lentiviral vector production

High titer lentiviral vector supernatant encoding DsRED T2A SATB1, YFP T2A Foxp3 and control plasmids alone was collected. For silencing of Foxp3 and SATB1 in human Treg cells, miR RNAi targeting Foxp3 and SATB1 were designed, cloned into the pcDNA6.2-GW+EmGFP-miR vector, chained and recombined into the pLenti6.3 expression vectors (Invitrogen). For transduction of murine expanded Treg cells, SATB1 was cloned into the pLVTHM expression vector in front of an IRES-Thy1.1 sequence53.

Lentiviral Foxp3 and SATB1 transductions of human CD4+ T cells

Human CD4+CD25+ Treg cells were stimulated for 24 h with CD3 and CD28-coated beads in the presence of IL-2. After this initial stimulation, Treg cells were lentivirally transduced with a pELNS DsRED 2A SATB1 or control plasmids containing DsRED as previously described resulting in a 1:1 expression of DsRED and the transgene39, expanded for 6 days in the presence of CD3 and CD28-coated beads and IL-2, sorted on DsRED-positive cells on a MoFlo sorter (DakoCytomation) and used for further experiements.

Filter retention analysis

Each individual 32P-radiolabeled dsDNA sequence (14 nM) was incubated with increasing concentrations of Foxp3 protein for 30 min at 37 °C in 25 µl of binding buffer (KCl-Tris, pH 7.6, 5% Glycerol, 3 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT) in the presence of 1 µg/ml tRNA (Roche) and 50 µg/ml BSA. After incubation, the binding reaction was filtered through pre-wet 0.45 µm nitrocellulose filter membrane (Millipore) to co-retain protein and bound DNA. Membranes were washed and the amount of bound DNA-protein complexes determined by autoradiography.

Expansion of mouse Treg cells

CD4+CD25+GFP+ Treg cells were isolated from lymph nodes and spleens of DEREG mice. Cells were pre-enriched with the mouse CD4+ T cell isolation kit according to manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotech). Following enrichment, cells were stained with CD4, CD25, CD3, and CD8α. Cells were sorted on a FACS Aria III (BD) (purity > 98.0%). Cells were expanded in vitro by activation with Dynabead mouse T cell activator CD3+CD28-coated microbeads (3:1 bead to Treg cell ratio, Invitrogen) with exogenous IL-2 (2000 IU/ml, Proleukin) as previously described54.

Lentiviral transductions of mouse Treg cells

After expansion for 10 to 14 days in the presence of CD3+CD28-coated beads and IL-2, murine Treg cells were lentivirally transduced with a pLVTHM-SATB1-IRES-Thy1.1 plasmid or control plasmids. Therefore, 2.5×105 cells per well were transduced in 500 µl total volume of fresh culture media in a 24-well plate containing lentivirus (20 TU/cell) and protamine sulfate (8 µg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were spin-inoculated by centrifugation at 1000×g for 90 min at 30°C, fresh medium was added and cells were incubated for an additional 2 h at 37 °C. Afterwards, cells were washed several times and cultivated in the presence of CD3+CD28-coated beads and IL-2. Transgene expression was assessed no earlier than 72 h post-transduction. SATB1-Thy1.1-transduced, control-transduced or non-transduced expanded Treg cells were sorted on GFP and Thy1.1 expression or GFP expression alone on a FACS Aria III (BD) and used for further experiments.

Induction and assessment of colitis

Splenocyte samples were enriched for CD4+ T cells by negative selection on MACS columns with the CD4+ T cell isolation kit II (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were then stained with CD45RB, CD25, CD4, CD8α, and CD3 (all from BD) and naïve CD4+CD25−CD45RBhi T cells were sorted on a FACS Aria III. Inflammatory bowel disease was induced by the adoptive transfer of 6 ×105 naïve CD4+CD45RBhi T cells that were purified from C57BL/6 mice into Rag2−/− animals by tail vain injection. Mice that received 1 × 105 control-transduced expanded CD4+GFP+ Treg cells from DEREG mice at the same time as the naïve CD4+CD45RBhi T cells served as controls. To test the function of SATB1-expressing Treg cells, mice received 1 × 105 SATB1-transduced expanded CD4+GFP+ Treg cells from DEREG mice together with the naïve CD4+CD45RBhi T cells. Recipient mice were weighed 3 times per week and monitored for signs of illness. After 9 weeks, the animals were sacrificed, and the mesenteric and peripheral lymph nodes as well as spleen were analyzed by flow cytometry. For histological analysis, the large intestine (from the ileo-ceco-colic junction to the anorectal junction) was removed, fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution, and routinely processed for histological examination. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and assigned scores as described55. All samples were coded and assigned scores by researchers 'blinded' to the experimental conditions.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-tests and ANOVA with LSD were performed with SPSS 19.0 software.

Additional methods

More detailed information on mice, reagents, antibodies, plasmids, experimental procedures, and the generation of lentiviral vectors is available in the Supplementary Methods.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Mai, M. Kraut, S. Keller, N. Kuhn, J. Birke, I. Büchmann, A. Dolf, and P. Wurst for technical assistance, M. Hoch, M. Pankratz, S. Burgdorf, A. Popov, A. Staratschek-Jox as well as all other lab members for discussions and J. Oldenburg for providing us with blood samples from healthy individuals. J.L.S. and M.B. are funded by the German Research Foundation (SFB 832, SFB 704, INST 217/576-1, INST 217/577-1), the Wilhelm-Sander-Foundation, the German Cancer Aid, the German Jose-Carreras-Foundation, the BMBF (NGFN2), and the Humboldt-Foundation (Sofja-Kovalevskaja Award). B.R.B. and K.L.H. are funded by a translational research grant from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of America (R6029-07). X.Z., S.L.B.-B., and J.A.B. are funded by the Juvenile Diabetes Research foundation Scholar #16-2008-643, and UCSF Autoimmunity Center of Excellence. S.C.B. supported by NHMRC project grants 339123, 565314. B.S. is funded by the German Research Foundation (SCHE 1562; SFB832). S.B. T.G. and J.L.R are funded by JDRF Collaborative Centers for Cell Therapy and the JDRF Center on Cord Blood Therapies for Type 1 Diabetes.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Immunology website.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.B. designed, performed and supervised experiments, analyzed data, wrote the manuscript; Y.T. performed qPCR, CBA, WB, overexpression experiments and filter retention analysis, analyzed data; R.M. designed and performed reporter assays; S.C. performed experiments, analyzed data; T.S. performed ChIP experiments, analyzed data; K.L. and C.T.M. performed experiments with DEREG mice; S.B. and T.G. performed overexpression experiments; E.S. performed and analyzed immunofluorescence experiments; W.K. performed histone methylation studies, S.L.B.-B. and X.Z. performed experiments with Dicer1fl/fl mice; A.H. performed bioinformatic analysis; D.S. generated lentiviral contructs; S.D.P. performed microarray experiments; E.E. performed FACS sorting; J.B. and A.L. performed experiments with Rag2−/− mice; P.A.K. was involved in study design; K.L.H. and B.R.B. provided vital analytical tools; R.B. provided vital analytical tools; T.Q. supervised and analyzed immunofluorescence experiments; C.W: performed IHC; A.W. performed, designed and supervised DNA methylation experiments; G.M. and M.F. designed and supervised filter retention experiments; W.K. designed and supervised experiments, wrote the manuscript; B.S. designed and analyzed reporter assays; S.C.B. designed and supervised ChIP experiments; T.S. designed and supervised experiments with DEREG mice, provided vital analytical tools; J.A.B. designed and supervised experiments with Dicer1fl/fl mice; J.L.R. designed and supervised SATB1 overexpression experiments, wrote the manuscript; J.L.S. designed, supervised and analyzed experiments, wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

Research support to J.L.S. and M.B. has in part been provided by Becton Dickinson.

R.B. is currently employed by Becton Dickinson, S.C. by Miltenyi Biotech.

J.L.S., M.B. and R.B. have applied for several US and international patents on Treg cell biology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin W, et al. Regulatory T cell development in the absence of functional Foxp3. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:359–368. doi: 10.1038/ni1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wan YY, Flavell RA. Regulatory T-cell functions are subverted and converted owing to attenuated Foxp3 expression. Nature. 2007;445:766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature05479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lahl K, et al. Nonfunctional regulatory T cells and defective control of Th2 cytokine production in natural scurfy mutant mice. J Immunol. 2009;183:5662–5672. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams LM, Rudensky AY. Maintenance of the Foxp3-dependent developmental program in mature regulatory T cells requires continued expression of Foxp3. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:277–284. doi: 10.1038/ni1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Shea JJ, Paul WE. Mechanisms underlying lineage commitment and plasticity of helper CD4+ T cells. Science. 2010;327:1098–1102. doi: 10.1126/science.1178334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy KM, Stockinger B. Effector T cell plasticity: flexibility in the face of changing circumstances. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:674–680. doi: 10.1038/ni.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feuerer M, Hill JA, Mathis D, Benoist C. Foxp3+ regulatory T cells: differentiation, specification, subphenotypes. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:689–695. doi: 10.1038/ni.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee YK, Mukasa R, Hatton RD, Weaver CT. Developmental plasticity of Th17 and Treg cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gavin MA, et al. Foxp3-dependent programme of regulatory T-cell differentiation. Nature. 2007;445:771–775. doi: 10.1038/nature05543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan F, et al. Eos mediates Foxp3-dependent gene silencing in CD4+ regulatory T cells. Science. 2009;325:1142–1146. doi: 10.1126/science.1176077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ouyang W, et al. Foxo proteins cooperatively control the differentiation of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:618–627. doi: 10.1038/ni.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harada Y, et al. Transcription factors Foxo3a and Foxo1 couple the E3 ligase Cbl-b to the induction of Foxp3 expression in induced regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1381–1391. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng Y, et al. Regulatory T-cell suppressor program co-opts transcription factor IRF4 to control T(H)2 responses. Nature. 2009;458:351–356. doi: 10.1038/nature07674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhry A, et al. CD4+ regulatory T cells control TH17 responses in a Stat3-dependent manner. Science. 2009;326:986–991. doi: 10.1126/science.1172702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ziegler SF. FOXP3: of mice and men. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:209–226. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chong MM, Rasmussen JP, Rudensky AY, Littman DR. The RNAseIII enzyme Drosha is critical in T cells for preventing lethal inflammatory disease. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2005–2017. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liston A, Lu LF, O'Carroll D, Tarakhovsky A, Rudensky AY. Dicer-dependent microRNA pathway safeguards regulatory T cell function. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1993–2004. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou X, et al. Selective miRNA disruption in T reg cells leads to uncontrolled autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1983–1991. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Floess S, et al. Epigenetic control of the foxp3 locus in regulatory T cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li B, et al. FOXP3 interactions with histone acetyltransferase and class II histone deacetylases are required for repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4571–4576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700298104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou X, Bailey-Bucktrout S, Jeker LT, Bluestone JA. Plasticity of CD4(+) FoxP3(+) T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alvarez JD, et al. The MAR-binding protein SATB1 orchestrates temporal and spatial expression of multiple genes during T-cell development. Genes Dev. 2000;14:521–535. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cai S, Han HJ, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. Tissue-specific nuclear architecture and gene expression regulated by SATB1. Nat Genet. 2003;34:42–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yasui D, Miyano M, Cai S, Varga-Weisz P, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. SATB1 targets chromatin remodelling to regulate genes over long distances. Nature. 2002;419:641–645. doi: 10.1038/nature01084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dickinson LA, Joh T, Kohwi Y, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. A tissue-specific MAR/SAR DNA-binding protein with unusual binding site recognition. Cell. 1992;70:631–645. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90432-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cai S, Lee CC, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. SATB1 packages densely looped, transcriptionally active chromatin for coordinated expression of cytokine genes. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1278–1288. doi: 10.1038/ng1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfoertner S, et al. Signatures of human regulatory T cells: an encounter with old friends and new players. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R54. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-7-r54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng Y, et al. Genome-wide analysis of Foxp3 target genes in developing and mature regulatory T cells. Nature. 2007;445:936–940. doi: 10.1038/nature05563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugimoto N, et al. Foxp3-dependent and -independent molecules specific for CD25+CD4+ natural regulatory T cells revealed by DNA microarray analysis. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1197–1209. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lund R, et al. Identification of genes involved in the initiation of human Th1 or Th2 cell commitment. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:3307–3319. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen W, et al. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25- naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1875–1886. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lahl K, et al. Selective depletion of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induces a scurfy-like disease. J Exp Med. 2007;204:57–63. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anz D, et al. Immunostimulatory RNA Blocks Suppression by Regulatory T Cells. J Immunol. 184:939–946. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuczma M, et al. Foxp3-deficient regulatory T cells do not revert into conventional effector CD4+ T cells but constitute a unique cell subset. J Immunol. 2009;183:3731–3741. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0800601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishihara Y, Ito F, Shimamoto N. Increased expression of c-Fos by extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation under sustained oxidative stress elicits BimEL upregulation and hepatocyte apoptosis. Febs J. 2011;278:1873–1881. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szymczak AL, et al. Correction of multi-gene deficiency in vivo using a single 'self-cleaving' 2A peptide-based retroviral vector. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:589–594. doi: 10.1038/nbt957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei G, et al. Global mapping of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 reveals specificity and plasticity in lineage fate determination of differentiating CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;30:155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu LF, et al. Foxp3-dependent microRNA155 confers competitive fitness to regulatory T cells by targeting SOCS1 protein. Immunity. 2009;30:80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kohlhaas S, et al. Cutting edge: the Foxp3 target miR-155 contributes to the development of regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:2578–2582. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marson A, et al. Foxp3 occupancy and regulation of key target genes during T-cell stimulation. Nature. 2007;445:931–935. doi: 10.1038/nature05478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kitoh A, et al. Indispensable role of the Runx1-Cbfbeta transcription complex for in vivo-suppressive function of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2009;31:609–620. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rudra D, et al. Runx-CBFbeta complexes control expression of the transcription factor Foxp3 in regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1170–1177. doi: 10.1038/ni.1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahlfors H, et al. SATB1 dictates expression of multiple genes including IL-5 involved in human T helper cell differentiation. Blood. 2010;116:1443–1453. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-252205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koch MA, et al. The transcription factor T-bet controls regulatory T cell homeostasis and function during type 1 inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:595–602. doi: 10.1038/ni.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou X, et al. Instability of the transcription factor Foxp3 leads to the generation of pathogenic memory T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1000–1007. doi: 10.1038/ni.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oldenhove G, et al. Decrease of Foxp3+ Treg cell number and acquisition of effector cell phenotype during lethal infection. Immunity. 2009;31:772–786. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brunkow ME, et al. Disruption of a new forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse. Nat Genet. 2001;27:68–73. doi: 10.1038/83784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Classen S, et al. Human resting CD4+ T cells are constitutively inhibited by TGF beta under steady-state conditions. J Immunol. 2007;178:6931–6940. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sadlon TJ, et al. Genome-wide identification of human FOXP3 target genes in natural regulatory T cells. Journal of immunology. 2010;185:1071–1081. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wiznerowicz M, Trono D. Conditional suppression of cellular genes: lentivirus vector-mediated drug-inducible RNA interference. Journal of virology. 2003;77:8957–8961. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8957-8961.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang Q, et al. In vitro-expanded antigen-specific regulatory T cells suppress autoimmune diabetes. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2004;199:1455–1465. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.ten Hove T, et al. Dichotomal role of inhibition of p38 MAPK with SB 203580 in experimental colitis. Gut. 2002;50:507–512. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.4.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.