Abstract

Objective

To compare the incidences of preterm delivery, cervical incompetence treated by cerclage, placental implantation or retention problems (ie, placenta praevia, placental abruption and retained placenta) and postpartum haemorrhage between women with and without a history of pregnancy termination.

Design

A retrospective cohort study using aggregated data from a national perinatal registry.

Setting

All midwifery practices and hospitals in the Netherlands.

Participants

All pregnant women with a singleton pregnancy without congenital malformations and a gestational age of ≥20 weeks who delivered between January 2000 and December 2007.

Main outcome measures

Preterm delivery, cervical incompetence treated by cerclage, placenta praevia, placental abruption, retained placenta and postpartum haemorrhage.

Results

A previous pregnancy termination was reported in 16 000 (1.2%) deliveries. The vast majority of these (90–95%) were performed by surgical methods. The incidence of all outcome measures was significantly higher in women with a history of pregnancy termination. Adjusted ORs (95% CI) for cervical incompetence treated by cerclage, preterm delivery, placental implantation or retention problems and postpartum haemorrhage were 4.6 (2.9 to 7.2), 1.11 (1.02 to 1.20), 1.42 (1.29 to 1.55) and 1.16 (1.08 to 1.25), respectively. Associated numbers needed to harm were 1000, 167, 111 and 111, respectively. For any listed adverse outcome, the number needed to harm was 63.

Conclusions

In this large nationwide cohort study, we found a positive association between surgical termination of pregnancy and subsequent preterm delivery, cervical incompetence treated by cerclage, placental implantation or retention problems and postpartum haemorrhage in a subsequent pregnancy. Absolute risks for these outcomes, however, remain small. Medicinal termination might be considered first whenever there is a choice between both methods.

Keywords: termination of pregnancy, preterm delivery, cervical incompetence, placenta praevia, placental abruption, retained placenta

Article summary.

Article focus

To estimate the influence of pregnancy termination on the outcome of subsequent pregnancies.

Does termination of pregnancy lead to cervical incompetence and/or preterm delivery in subsequent pregnancies?

Is termination of pregnancy associated with a higher risk of placental implantation or retention problems (ie, placenta praevia, placental abruption and retained placenta) in a subsequent pregnancy?

Key messages

Surgical termination of pregnancy is positively associated with subsequent spontaneous preterm delivery, cervical incompetence treated by cerclage, placental implantation/retention problems and postpartum haemorrhage in a subsequent singleton pregnancy.

Strengths and limitations of this study

One of the largest cohort studies on reproductive outcomes of women with and without a history of pregnancy termination.

Registration of and adjustment for many potential confounders.

The perinatal registry contains no information on the technique of pregnancy termination.

The number of, and gestational age at, pregnancy terminations in a given woman was not registered.

Under-reporting of pregnancy termination leads to an underestimation of its effect on future reproduction.

Introduction

Worldwide each year, at least 43 million pregnancies are terminated, often in young nulliparous women.1 Data on the effect on future pregnancies suggest an increase in risk for complications in subsequent pregnancies after pregnancy termination.2–13

In the Netherlands, approximately 32 000 pregnancies are terminated each year.14 The abortion rate has been unchanged since 2001 with 8.8 per thousand women of childbearing age (15–44 years) resident in the Netherlands having a pregnancy terminated each year.14 The vast majority (90–95%) of these abortions are performed in specialised clinics by surgical methods, namely vacuum aspiration and curettage.14 15 In 1999, medicinal abortion with a combination of antiprogestagens and prostaglandins has been introduced in clinical practice. However, in the Netherlands, this method is mainly used for termination of pregnancy for medical or genetic reasons and usually not offered as an alternative to women requesting abortion for non-medical reasons.

The question arises how women should be counselled as to the effect of surgical abortion on future reproductive performance. We therefore set out to compare the incidences of (1) preterm delivery, (2) cervical incompetence treated by cerclage, (3) placental implantation or retention problems (PIRP) which include placenta praevia, placental abruption and retained placenta and (4) postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) in pregnancies of women with and without a history of pregnancy termination.

Methods

Study population

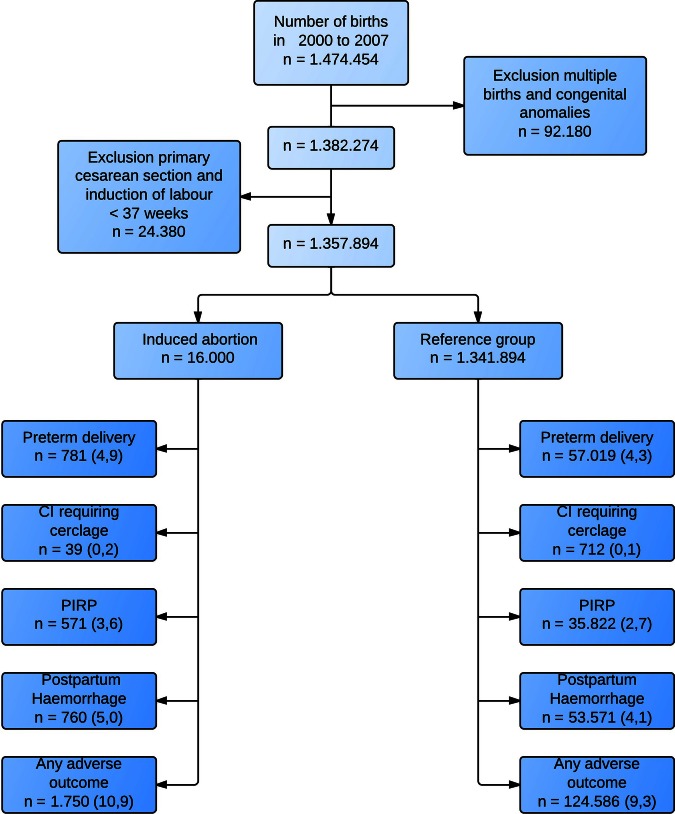

Prospectively collected data were derived from the Netherlands Perinatal Registry (PRN).16 PRN is a Dutch nationwide database that contains demographics and information about mothers and newborns, courses and outcomes of pregnancy, and content and organisation of care, all entered by healthcare providers. Around 96% of all deliveries from 20 weeks of gestation onwards are registered in PRN. The database consists of three linked and validated registries: the national obstetric database for midwives (LVR-1), the national obstetric database for gynaecologists (LVR-2) and the national neonatal/pediatric database (LNR).17 18 The study period was from January 2000 to December 2007. We chose this period to avoid bias, because medicinal termination of pregnancy was not commonly used at that time, the majority of pregnancy terminations being performed surgically. All multiple births and births of infants with a congenital anomaly in index pregnancies were excluded. Also, all women where labour was induced or a planned caesarean section was performed before 37 weeks’ gestation, that is, iatrogenic preterm deliveries, were excluded (figure 1). Information on whether there had been a previous termination of pregnancy or not was registered based on responses given by the pregnant woman in a predefined pregnancy intake questionnaire, among others on reproductive history. In Dutch, different terminology is used for pregnancy termination as opposed to miscarriage. This questionnaire is being filled out at the first prenatal visit, usually at around 12 weeks of pregnancy. The number of pregnancy terminations in an individual woman is not registered in PRN. The primary study outcomes were preterm delivery, cervical incompetence with placement of a cerclage, PIRP and PPH.

Figure 1.

Patient selection. Preterm delivery: delivery at a gestational age between 20 and 37 weeks. CI treated by cerclage: cervical incompetence treated by cerclage. Placental implantation and retention problems (PIRP): placenta praevia, placental abruption or retained placenta.

Definitions

Preterm delivery was registered from 20 weeks on and so, for this study, we therefore defined preterm delivery as delivery between 20 and 37 weeks of gestation. The aim of the study was to document any registered possible adverse effects. For a subgroup analysis of gestational age at delivery, we divided gestational age into five groups: 20+0 to 23+6 weeks, 24+0 to 28+6 weeks, 29+0 to 32+6 weeks, 33+0 to 36+6 weeks and 37 weeks and later. In the Netherlands, a cervical cerclage is considered to be indicated when there is shortening or dilation of the cervix without contractions during the second trimester of pregnancy.19 20 A history of pregnancy termination is not a reason for cerclage.

Placenta praevia, placental abruption and retained placenta have been merged into the composite measure PIRP because of the low incidence of these outcomes. Retained placenta also includes postpartum curettage for incomplete placenta. PPH was defined as more than 1000 ml estimated blood loss postpartum.

Prior cervical surgery includes conisation or amputation of the cervix. Polyhydramnios was defined as an estimated amount of amniotic fluid of more than 2 liters, diagnosed by ultrasound during pregnancy.21 Perinatal mortality was defined as stillbirth or death up to 7 days after birth, after a gestation period of at least 22 weeks (WHO definition).

Socioeconomic status (SES) was based on the average income level of the neighbourhood, which was determined by the first four digits of the woman's postal code, a common method for establishing SES in the Netherlands.

Statistical analysis

We used t tests and χ2 tests to compare baseline characteristics and the difference in incidence of outcome measures between both groups. Logistic regression analysis was performed to calculate crude ORs (cORs) and adjusted ORs (aORs) and their 95% CIs. ORs were adjusted for variables that are considered as possible confounders in the literature: maternal age, gravidity, parity, SES, ethnicity, smoking, drug dependence, pyelitis, polyhydramnios, current uterus myomatosus, history of preterm delivery, history of cervical incompetence, history of placenta praevia, history of placental abruption, history of manual removal of the placenta, history of PPH (not due to perineal trauma) and history of cervical surgery.22–27

A subgroup analysis of various categories of gestational age was performed for the outcome preterm delivery because a deleterious effect of cervical dilation at time of delivery could be larger at early gestational ages.

We computed a number needed to harm (1/risk difference) in which the risk difference equalled the estimated incidence in women with a history of pregnancy termination minus the incidence among women without a history of pregnancy termination. All analyses were performed using SPSS V.19. Ethical approval was obtained from the board and privacy commission of PRN.

Results

During the study period, 1 357 894 singletons were born who fulfilled the selection criteria (figure 1). In 16 000 deliveries (1.2%), the mother reported a history of pregnancy termination. Women with a history of pregnancy termination were more often younger than 20 or older than 35 years, were more often nulliparous, of non-Dutch origin, of lower SES and smoked more often (table 1). The incidences of preterm delivery, cervical incompetence treated by cerclage, PIRP and PPH are shown in table 2. Cervical incompetence treated by cerclage was more frequently present in the group with a history of pregnancy termination (0.2% vs 0.1%; p<0.001). Preterm delivery, PIRP and PPH were also more common in the group with a history of pregnancy termination. All associations remained statistically significant after adjustment for possible confounders. The strongest association was found between cervical incompetence treated by cerclage and pregnancy termination with an aOR of 4.6 (95% CI 2.9 to 7.2). The aORs for preterm delivery, PIRP and PPH are shown in table 2. Any listed adverse outcome occurred in 10.9% of the 16 000 deliveries with a history of pregnancy termination versus 9.3% in the reference group and showed an aOR of 1.15 (95% CI 1.09 to 1.22). The absolute risk difference for any listed adverse outcome amounted to 1.6% with a number needed to harm of 63 women.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | History of termination of pregnancies (%) | Reference group (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Study population | 16000 | 1341894 |

| Maternal age* | ||

| Mean (SD) | 30.41 (5.8) | 30.40 (48) |

| <20 | 525 (3.3) | 22786 (17) |

| 20–25 | 2983 (18.6) | 187355 (14) |

| 26–30 | 4085 (25.5) | 447307 (33.3) |

| 31–35 | 5186 (32.4) | 495546 (36.9) |

| >35 | 3219 (20.1) | 188591 (14.1) |

| Parity* | ||

| 0 | 9265 (57.9) | 613755 (45.7) |

| 1 | 4692 (29.3) | 485287 (36.2) |

| 2 | 1453 (9.1) | 169802 (12.7) |

| 3 | 417 (2.6) | 46910 (3.5) |

| ≥4 | 172 (1.1) | 25822 (1.9) |

| SES* | ||

| High | 3469 (21.7) | 314667 (23.4) |

| Normal | 5488 (34.3) | 608113 (45.3) |

| Low | 6861 (43) | 402254 (30) |

| Ethnicity* | ||

| Dutch | 10304 (64.4) | 1093438 (81.5) |

| Mediterranean | 1184 (7.4) | 105368 (7.9) |

| Other European | 1012 (6.3) | 33728 (2.5) |

| Creole | 1441 (9) | 30226 (2.3) |

| Hindu | 341 (2.1) | 14523 (1.1) |

| Asian | 605 (3.8) | 24408 (1.8) |

| Other | 1086 (6.8) | 31519 (2.3) |

| Smoking* | 180 (1.1) | 5712 (0.4) |

| Drug dependence* | 91 (0.6) | 1232 (0.09) |

| Reproductive history | ||

| Preterm delivery* | 165 (1) | 16122 (1.2) |

| Cervical incompetence/Shirodkar procedure | 3 (0.02) | 381 (0.03) |

| Placenta praevia* | 8 (0.05) | 183 (0.01) |

| Placental abruption | 17 (0.1) | 2023 (0.2) |

| Manual removal of the placenta | 75 (0.5) | 7353 (0.5) |

| Postpartum haemorrhage* | 156 (1) | 19062 (1.4) |

| Caesarean section* | 839 (5.2) | 101884 (7.6) |

| Cervical surgery* | 28 (0.2) | 1424 (0.1) |

| Uterine myoma* | 79 (0.5) | 4732 (0.4) |

| Myomectomy subserous | 5 (0.03) | 257 (0.02) |

| Myomectomy submucous/intramural | 4 (0.03) | 409 (0.03) |

| Index gravidity | ||

| Pyelitis* | 20 (0.1) | 736 (0.05) |

| Polyhydramnios | 5 (0.03) | 234 (0.02) |

| Mode of delivery* | ||

| Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 12048 (75.4) | 1024044 (76.4) |

| Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1682 (10.5) | 143654 (10.7) |

| Elective caesarean delivery | 738 (4.6) | 70345 (5.2) |

| Emergency caesarean delivery | 1520 (9.5) | 102090 (7.6) |

| Perinatal mortality* | 109 (0.7) | 7602 (0.6) |

*p<0.05.

SES, socioeconomic status.

Table 2.

Pregnancy outcomes in patients with and without a history of pregnancy termination

| Outcome | History of termination of pregnancies (%) | Reference group (%) | Risk difference | NNH | cOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical incompetence treated by cerclage | 39 (0.2) | 712 (0.1) | 0.1 | 1000 | 4.60 (3.33 to 6.36) | 4.58 (2.93 to 7.15) |

| SPTB | 781 (4.9) | 57019 (4.3) | 0.6 | 167 | 1.15 (1.07 to 1.23) | 1.11 (1.02 to 1.20) |

| SPTB <32 weeks | 150 (0.9) | 7788 (0.6) | 0.3 | 333 | 1.61 (1.37 to 1.89) | 1.52 (1.26 to 1.85) |

| SPTB <28 weeks | 85 (0.5) | 3984 (0.3) | 0.2 | 500 | 1.78 (1.43 to 2.21) | 1.67 (1.30 to 2.15) |

| PIRP | 571 (3.6) | 35822 (2.7) | 0.9 | 111 | 1.35 (1.25 to 1.47) | 1.32 (1.21 to 1.43) |

| Placenta praevia | 41 (0.3) | 1315 (0.1) | 0.2 | 500 | 2.62 (1.92 to 3.58) | 2.48 (1.80 to 3.42) |

| Placental abruption | 22 (0.1) | 1074 (0.1) | 0 | – | 1.72 (1.13 to 2.62) | 1.56 (1.02 to 2.39) |

| Retained placenta | 512 (3.2) | 33521 (2.5) | 0.7 | 142 | 1.30 (1.19 to 1.42) | 1.26 (1.15 to 1.38) |

| Postpartum haemorrhage | 760 (5) | 53571 (4.1) | 0.9 | 111 | 1.22 (1.14 to 1.32) | 1.16 (1.08 to 1.25) |

| Any listed adverse outcome | 1750 (10.9) | 124586 (9.3) | 1.6 | 63 | 1.20 (1.14 to 1.26) | 1.15 (1.09 to 1.22) |

| Any listed adverse outcome other than cervical incompetence treated by cerclage | 1726 (10.8) | 124119 (9.2) | 1.6 | 63 | 1.19 (1.13 to 1.25) | 1.14 (1.08 to 1.21) |

p Value for all outcomes <0.001.

aOR are adjusted for known confounders for the given outcome. SPTB and cervical incompetence treated by cerclage are adjusted for maternal age, ethnicity, SES, parity, smoking, drug dependence, pyelitis, polyhydramnios, history of SPTB, history of cervical incompetence or Shirodkar procedure, history of uterine myoma and history of cervical surgery.

aOR of PIRP, placenta praevia, placental abruption and retained placenta are adjusted for maternal age, ethnicity, SES, parity, smoking, drug dependence, history of caesarean section and history of PIRP.

aOR of PPH is adjusted for maternal age, ethnicity, SES, parity, polyhydramnios, history of PPH and history of uterine myoma.

aOR of composite outcome is adjusted for all the above-mentioned parameters.

aOR, adjusted OR; cOR, crude OR; NNH, number needed to harm; PIRP, placental implantation or retention problems; PPH, postpartum haemorrhage; SES, socioeconomic status; SPTB, spontaneous preterm birth (gestational age from 20 to 37 weeks).

A subgroup analysis in gestational age at delivery categories showed that previous termination of pregnancy had the strongest association with preterm delivery at early gestational ages (table 3). The strongest association was found for delivery between 20+0 and 23+6 weeks, cOR 1.83 (95% CI 1.35 to 2.48) and aOR 1.61 (95% CI 1.13 to 2.30).

Table 3.

Gestational age at delivery in women with and without a history of pregnancy termination

| Gestational age (weeks) | History of termination of pregnancies (%) | Reference group (%) | cOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20+0–23+6 | 43 (0.3) | 1966 (0.1) | 1.83 (1.35 to 2.48) | 1.61 (1.13 to 2.30) |

| 24+0–28+6 | 56 (0.4) | 2658 (0.2) | 1.76 (1.35 to 2.30) | 1.67 (1.22 to 2.28) |

| 29+0–32+6 | 80 (0.5) | 5393 (0.4) | 1.24 (0.99 to 1.55) | 1.36 (1.07 to 1.74) |

| 33+0–36+6 | 602 (3.8) | 47002 (3.5) | 1.07 (0.99 to 1.16) | 1.04 (0.95 to 1.14) |

| ≥37 | 15152 (95.1) | 1268013 (95.7) | Reference group | Reference group |

aORs are adjusted for maternal age, ethnicity, SES, parity, smoking, drug dependence, pyelitis, polyhydramnios, history of SPTB, history of cervical incompetence or Shirodkar procedure, history of uterine myoma and history of cervical surgery.

aOR, adjusted OR; cOR, crude OR; SES, socioeconomic status; SPTB, spontaneous preterm birth.

Discussion

The most important finding of this study was that termination of pregnancy is associated with an increased risk for preterm delivery, cervical incompetence, PIRP and PPH in a subsequent singleton pregnancy.

In the study period, 90–95% of pregnancy terminations were performed surgically.14 15 We therefore assume that the observed increased risks are related to surgical abortion. Cervical dilation for terminating pregnancy can damage the cervix and cause cervical incompetence, leading to preterm delivery.28 This risk is, among others, dependent on gestational age at termination and extent of dilation. Placental implantation and retention problems are known to occur more often after uterine trauma such as previous caesarean delivery or uterine surgery.29

A recent study in Scotland showed that surgical abortion was associated with a higher risk of preterm birth in a subsequent pregnancy than medicinal abortion.2 The combined use of Mifegyne and misoprostol is a safe medicinal alternative to surgical abortion, but it is associated with a higher frequency of incomplete expulsion and longer postabortion bleeding.30–32 Therefore, after 8 weeks of pregnancy, it is mainly performed in a clinical setting. Studies on patient preferences show a high acceptability for both procedures, although the acceptability of medicinal abortion declines with increasing gestational age.31 33

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

The major strengths of this study are the size of the cohort, the uniform coverage of almost all deliveries nationwide, the standardised history taking in all obstetric practices and the accurate documentation of history and pregnancy complications.

A limitation of this study is that a history of pregnancy termination is probably selectively reported (ie, under-reported) by pregnant women. The relatively low prevalence of a history of pregnancy termination in our database compared with the Dutch abortion registry and another (urban, high-risk) cohort study further marks this.34 35 Presuming that women who did not report having had a history of termination had the same risk of adverse outcome as those who did report this, under-reporting has most likely weakened the associations in our study.

Second, some women have delivered more than once during the study period, and the sequence of various pregnancy outcomes is not known. Women may therefore have multiple records in the registry. These records cannot be linked to one another in the PRN data yet and therefore no adjustment could be made.

Another limitation is that curettage for spontaneous miscarriage is not registered in PRN. Often, this does not require dilation, but the technique of uterine evacuation is the same. These women are now undetected in the reference group, leading to an underestimation of the effect of intrauterine manipulation on future reproduction. Furthermore, neither gestational age at the moment of pregnancy termination nor the number of terminations or the techniques of termination were available in the registry. In the Netherlands, 58% of pregnancy terminations are performed before 8 weeks. In two-thirds of the women registered in the (legally required) abortion registry, it was the first termination, one quarter had one previous termination and the remaining group had two or more previous terminations.34

Comparison with other studies

Previous literature suggested a small but definitive risk for adverse outcome in pregnancies following surgical abortion. The large study of Bhattacharya et al2 used methods similar to ours and reported a higher risk of preterm birth and placental abruption in women with termination of pregnancy in their first pregnancy (n=67 745) versus women who had a live-birth in their first pregnancy (n=357 080; aOR 1.66 (95% CI 1.58 to1.74) and 1.49 (95% CI 1.25 to 1.77), respectively). Recently, Klemetti et al3 studied over 300 000 first-time mothers from a 12-year period in the Medical Birth Register and linked their data to a 25-year period in the Finnish Abortion Registry. They found an association between preterm birth and previous abortion, with worse outcomes after multiple abortions. The abortion rate in Finland is similar to the one in the Netherlands.34 A recent systematic review of Lowit et al4 reported an excess risk of preterm delivery of 5–12% (ORs 1.2–1.9) and an elevated risk of placenta praevia (ORs 1.3–1.7). Another systematic review and meta-analysis of Shah and Zao7 described a further increased risk for preterm delivery in women after two or more terminations of pregnancy (a history of 1 termination OR 1.36 (95% CI 1.24 to 1.50) and two or more terminations OR 1.93 (95% CI 1.28 to 2.71)). Haldre et al9 studied the occurrence of placenta complications in deliveries following an abortion and found a higher risk of retained placenta (aOR 1.23 (95% CI 1.1 to 1.38)). The range in ORs could be related to gestational age at the moment of termination. Termination of pregnancy at a lower gestational age requires less cervical dilation, and therefore the risk of cervical damage may be lower.

Implications of the study

Women who have had a termination of pregnancy have an increased risk of preterm delivery, cervical incompetence treated by cerclage, placental problems and PPH, although absolute risks are low. Medicinal termination may be safer for future pregnancies than surgical termination. For future research, we recommend including the technique of pregnancy termination in perinatal registries, as well as gestational age at termination and number of terminations. The issue of possible harm to future reproduction is not routinely addressed when informing patients about various alternatives for terminating pregnancy. We recommend that this information should be included whenever there is a choice between both methods. The data generated in this study can be used for this purpose.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: GCMLPC and AF initiated the study. BLS, GCMLPC and MPHK were involved in designing the study. BLS collected the data. BLS, MPHK and CWPMH analysed the data. All authors actively participated in interpreting the results and revising the manuscript, which was written by BLS, GCMLPC, MPHK, AF and CWPMH.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The board and privacy commission of the Netherlands Perinatal Registry approved this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The dataset is available on the Netherlands Perinatal Registry.

References

- 1.Sedgh G, Singh S, Shah IH, et al. Induced abortion: incidence and trends worldwide from 1995 to 2008. Lancet 2012;379:625–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhattacharya S, Lowit A, Bhattacharya S, et al. Reproductive outcomes following induced abortion: a national register-based cohort study in Scotland. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klemetti R, Gissler M, Niinimäki M, et al. Birth outcomes after induced abortion: a nationwide register-based study of births in Finland. Hum Reprod 2012;27:3315–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowit A, Bhattacharya S, Bhattacharya S. Obstetric performance following an induced abortion. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2010;24:667–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freak-Poli R, Chan A, Tucker G, et al. Previous abortion and risk of pre-term birth: a population study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2009;22:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voigt M, Henrich W, Zygmunt M, et al. Is induced abortion a risk factor in subsequent pregnancy? J Perinat Med 2009;37:144–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah PS, Zao J. Induced termination of pregnancy and low birth weight and preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analyses. BJOG 2009;116:1425–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown JS, Adera T, Masho SW. Previous abortion and the risk of low birth weight and preterm births. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:16–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haldre K, Rahu K, Karro H, et al. Previous history of surgically induced abortion and complications of the third stage of labour in subsequent normal vaginal deliveries. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2008;21:884–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reime B, Schücking BA, Wenzlaff P. Reproductive outcomes in adolescents who had a previous birth or an induced abortion compared to adolescents’ first pregnancies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2008;8:4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chasen ST, Kalish RB, Gupta M, et al. Obstetric outcomes after surgical abortion at ≥20 weeks’ gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;193:1161–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ancel PY, Lelong N, Papiernik E, et al. History of induced abortion as a risk factor for preterm birth in European countries: results from the EUROPOP survey. Hum Reprod 2004;19:734–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreau C, Kaminski M, Ancel PY, et al. Previous induced abortions and the risk of very preterm delivery: results of the EPIPAGE study. BJOG 2005;112:430–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee L, Wijsen C. Annual report Abortion Registration 2006. Utrecht: Rutgers NissoGroep, 2007. http://www.rutgerswpf.nl/sites/default/files/rapport_LAR_2006.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee L, Wijsen C. Annual report Abortion Registration 2007. Utrecht: Rutgers NissoGroep, 2008. (with a summary in English on page 7). http://www.rutgerswpf.nl/sites/default/files/rapport_LAR_2007.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perinatreg.nl [internet] Utrecht: The Netherlands Perinatal Registry. http://www.perinatreg.nl/home_english.

- 17.Méray N, Reitsma JB, Ravelli AC, et al. Probabilistic record linkage is a valid and transparent tool to combine databases without a patient identification number. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:883–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tromp M, Ravelli AC, Meray N, et al. An efficient validation method of probabilistic record linkage including readmissions and twins. Methods Inf Med 2008;47:356–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. NVOG Richtlijn “Preventie recidief spontane vroeggeboorte” 2007. (Guideline Dutch Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology: prevention relapse spontaneous preterm birth, March 2007). 2007. Utrecht. http://nvog-documenten.nl/index.php?pagina=/richtlijn/item/pagina.php&richtlijn_id=745 (accessed 23 Jan 2013)

- 20.Althuisius SM, Dekker GA, Geijn HP, et al. Cervical incompetence prevention randomized cerclage trial: study (CIPRACT). Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;185:1107–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Croom CS, Banias BB, Ramos-Santos E, et al. Do semiquantitative amniotic fluid indexes reflect actual volume? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992;167(4 Pt 1):995–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwee A, Bots ML, Visser GHA, et al. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: a prospective study in the Netherlands. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2006;124:187–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldenberg R, Culhane JF, Lams JD, et al. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 2008;371:75–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raatikainen K, Heiskanen N, Heinonen S. Induced abortion: not an independent risk factor for pregnancy outcome, but a challenge for health counseling. Ann Epidemiol 2006;16:587–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheiner E, Sarid L, Levy A, et al. Obstetric risk factors and outcome of pregnancies complicated with early postpartum haemorrhage: a population-based study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2005;18:149–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iyasu S, Saftlas AK, Rowley DL, et al. The epidemiology of placenta previa in the United States, 1979 through 1987. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993;68:1424–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaaf JM, Ravelli CJ, Mol BWJ, et al. Development of a prognostic model for predicting spontaneous singleton preterm birth. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2012;164:150–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitley KA, Trinchere K, Prutsman W, et al. Midtrimester dilation and evacuation versus prostaglandin induction: a comparison of composite outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205:386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwee A, Bots ML, Visser GHA, et al. Obstetric management and outcome of pregnancy in women with a history of caesarean section in the Netherlands. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2007;132:171–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Say L, Brahmi D, Kulier R, et al. Medical versus surgical methods for first trimester termination of pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002, (4) CD003037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robson SC, Kelly T, Howel D, et al. Randomised preference trial of medical versus surgical termination of pregnancy less than 14 weeks’ gestation (TOPS). Health Technol Assess 2009;13:19–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graziosi GCM, Mol BWJ, Reuwer PJH, et al. Misoprostol versus curettage in women with early pregnancy failure after initial expectant management: a randomized trial. Hum Reprod 2004;19:1894–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rørbye C, Nørgaard M, Nilas L. Medical versus surgical abortion: comparing satisfaction and potential confounders in a partly randomized study. Hum Reprod 2005;20:834–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Health Care Inspectorate. Annual report 2009 Termination of Pregnancy Act. The Hague; 2010 (with a summary in English on page 29)

- 35.Vrijkotte TGM.2012. Amsterdam Born Children and their Development (ABCD Study). Unpublished raw data.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.