Abstract

Objective

Owing to a lack of prospective studies, our aim was to evaluate diagnostic factors, in particular, motor and non-motor function tests, for prognostication of recovery time in patients with acute facial palsy (AFP).

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

University hospital.

Participants

259 patients with AFP.

Measurements

Clinical data, facial grading, electrophysiological motor function tests and other non-motor function tests were assessed for their contribution to recovery time.

Results

The predominant origin of AFP was idiopathic (59%) and traumatic (21%). At baseline, the House-Brackmann scale (HB) was >III in 46% of patients. Follow-up time was 5.6±9.8 months with a complete recovery rate of 49%. The median recovery time was 3.5 months (95% CI 2.2 to 4.7 months). The following variables were associated with faster recovery: Interval between onset of AFP and treatment <6 days versus ≥6 days (median recovery time in months 2.1 vs 6.5; p<0.0001); HB ≤III vs >III (2.2 vs 4.6; p=0.001); no versus presence of pathological spontaneous activity in first electromyography (EMG; 2.8 vs probability of recovery <50%; p<0.0001); no versus voluntary activity in EMG (probability of recovery <50% vs 3.1; p<0.0001); normal versus pathological ipsilateral electroneurography (1.9 vs 6.5; p=0.008), normal versus pathological stapedius reflexes (1.6 vs 3.3; p=0.003).

Conclusions

Start of treatment and grading, but most importantly EMG evaluated for pathological spontaneous activity and the stapedius reflex test are powerful prognosticators for estimating the recovery time from AFP. These results need confirmation in larger datasets.

Keywords: Neurophysiology

Article summary.

Article focus

Previous retrospective studies have found inconsistent, partially contradictory results concerning risk factors for worse outcome after acute facial palsy (AFP) beyond the applied treatment.

A degenerative lesion of the facial nerve may be the most important risk factor for worse outcome, but information on the diagnostic tests that are most effective to detect a degeneration lesion is not known.

We wanted to evaluate the role of diagnostic factors, in particular motor and non-motor function tests, for their value to prognosticate the recovery time in patients with AFP.

Key message

Facial electromyography and stapedius reflex testing are the most powerful tools for prognostication of recovery time after AFP.

Strengths and limitations of this study

One of the strengths of our study is its guaranteed prospective data collection using a standardised set of diagnostic tools applied in a Department of Neurology and a Department of Otorhinolaryngology together. This guaranteed a comprehensive modern set of diagnostic tools necessary to evaluate patients with AFP.

A limitation is that the results of the diagnostic test did not implicate treatment stratification. For instance, it might be interesting in a future prospective trial to randomise patients with high probability for worse outcome to a standard therapy versus a more aggressive drug treatment.

Introduction

Unilateral peripheral acute facial palsy (AFP) is the most frequent disease of the facial nerve. Most cases are finally diagnosed as idiopathic AFP (Bell's palsy) as a cause cannot be found.1 If the cause is obvious, causal treatment follows the underlying disease.2 Standard treatment of the AFP itself, especially for idiopathic AFP, is nowadays a tapered course of oral steroid.3 The complete recovery rate after early prednisolone treatment for Bell's palsy is about 85–94% within 9–12 months.3–5 Data for the overall recovery rate for any cause of AFP only are available from retrospective studies and are given as less than 77%.6 7 Next to the probability of recovering completely, the patient is interested in the recovery time. Interestingly, only a few retrospective studies have addressed this important issue in small samples with variable diagnostic scope and variable treatment.8–10 Kaplan-Meier curves to estimate the probability of recovery have so far been presented only in one prospective clinical phase III trial evaluating the efficacy of prednisolone and valaciclovir for treatment of Bell's palsy.5 10 Actually, it is not the underlying disease itself that primarily influences the probability of recovering completely from AFP but rather the severity of the peripheral facial nerve lesion that should predict the outcome. Therefore, it is proposed that diagnostic tests, especially electrophysiological tests, are helpful in predicting the outcome.11

We used a prospective data collection of a cohort of patients with unilateral peripheral AFP with standardised diagnostics and treatment to estimate the time course of complete clinical recovery from facial palsy. The second aim was to investigate the impact of patients’ and disease characteristics as well as diagnostic test results to prognosticate the time course of recovery beyond the effect of symptomatic standard treatment with corticosteroids.

Methods

Patients

A standardised prospective data collection was performed in the Departments of Otorhinolaryngology and Neurology of the University Hospital Jena, Germany. Beginning with 2007, the diagnostic procedures for patients with peripheral AFP were conformed and standardised for both departments. All patients were seen in both departments. Parts of the diagnostics were performed in the department of otorhinolaryngology and other investigations were performed in the department of neurology. The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee. Three hundred and thirty (330) adult patients with AFP who were admitted between March 2007 and February 2012, that is, within a period of 5 years, were the starting point for the present study. The present study focused on patients with AFP in the acute phase. Electrophysiology was ex ante defined as an important diagnostic tool to be evaluated. The acute phase was defined electrophysiologically. In case of a degenerative facial nerve lesion, pathological spontaneous activity can be monitored for about 120 days and regeneration potentials as a sign of nerve regeneration can typically be seen after this period of 120 days. Therefore, ten patients who presented for the first time later than 120 days after onset of the palsy were excluded. Using this definition, a further prerequisite for inclusion was an electrophysiological examination of the facial muscles on the affected side within 120 days after onset of the palsy. Sixty-one patients did not fulfil this inclusion criterion. Finally, 259 patients of our total cohort of 330 patients with facial palsy were included.

Diagnostics and main outcome measures

The patients received an otorhinolaryngological examination including ultrasound of the head and neck and a neurological examination. The origin of palsy was categorised into six groups: idiopathic (Bell's palsy), herpes zoster oticus (Ramsey-Hunt-syndrome), borreliosis, otogenic (in case of acute or chronic otitis media), traumatic (acute temporal bone trauma, postsurgical, malignant tumour) and other reasons. On the day of the first presentation, AFP was graded by the admitting physician according to the HB six-point facial grading system,12 and also according to the Stennert Index.13 14 The Stennert index classifies the face at rest (0–4 points; 0=normal to 4=complete loss of resting tone) and during motion (0–6 points; 0=normal to 6=no motion) separately. Clinically, the palsy was defined as complete if the patient presented with a complete loss of motor function in the affected hemiface or if the palsy deteriorated to a complete palsy during the inpatient course of treatment. Otherwise, the palsy was defined as incomplete palsy.

All patients were hospitalised. Treatment followed the underlying disease and the German guideline for the treatment of facial palsy.2 As symptomatic treatment, a tapered course of oral corticosteroids over 10 days was regarded as standard treatment.2 3 This conservative treatment was given to all patients. Laboratory tests included serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and were analysed for IgM and IgG antibodies against Borrelia, varicella zoster virus (VZV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), cytomegalovirus (CMV) and tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). In case of a positive borrelia ELISA, a borrelia IgM and IgG line immunoblot assay was performed. The presence of mucocutaneous vesicles in the external auditory canal, on the tympanic membrane or on the base of the tongue, or IgM antibodies detected in serum the viruses qualified for classification as virally associated facial palsy. Two or more diagnostic criteria were needed to fulfil the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis: recent erythema migrans, Borrelia antibodies in serum or CSF, CSF pleocytosis >5 WBC/mm3 CSF/serum index >1.5.

Electrodiagnostic tests to evaluate the facial motor function are described in detail elsewhere.11 15 Briefly, baseline electroneurography (ENG), blink reflex testing (BR) and needle electromyography (EMG) were performed as early as possible. If the first EMG was performed earlier than 14 days after onset, the examination was repeated. The following categorised diagnostic criteria were evaluated: ENG, prolonged latency (yes/no), peak-to-peak amplitude loss of ≥25% (yes/no); BR, R1 and R2 ipsilateral responses decreased in comparison to the contralateral side (yes/no); EMG, pathological spontaneous activity (yes/no), only single fibre activity or no activity during voluntary EMG (yes/no).

The other facial nerve function tests were categorised as follows: ipsilateral stapedius reflex test normal (yes/no); complete loss of gustatory function on the ipsilateral side using the three-drop-test (yes/no);16 lacrimal function by the Schirmer test (<10 mm/≥10 mm); vestibular function represented by normal caloric stimulation (yes/no).

A first EMG with evaluation of spontaneous and voluntary activities was performed in all 259 patients (100%), a second EMG in 153 patients (59%), and a third EMG in 66 patients (26%). ENG data was analysable in 223 patients, and 165 patients (64%) received a BR. The stapedial reflex test was evaluable in 205 patients (79%), the Schirmer test in 174 patients (67%), the gustatory function in 186 patients (72%), and data on vestibular function were complete for 195 patients (75%). Serology results were complete for 187 patients (72%).

Follow-up examinations always included an otorhinolaryngological examination and an EMG examination. Two physicians examined all patients. The first examination was performed after 6 weeks and then every 3 months until complete recovery or, in case of incomplete recovery with defective healing, until pathological spontaneous activity disappeared and the patients did not show any improvement for a further 3 months.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS, V.20.0. The primary outcome criterion was complete recovery of facial palsy defined as grade I on the HB scale indicating normal facial function. The χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables. All tests were two-tailed, and p values<0.05 were considered to be significant. Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed to calculate the probability of complete recovery over the period. The prognostic influence of the diagnostic variables on recovery was analysed with the log-rank test. Prognostic factors associated with significant impact on complete recovery with a probability value of <0.05 were included in three blocks of a multivariate analysis using Cox's proportional hazards model independent of the aetiology of facial palsy. The hazard ratio of the multivariate Cox regression model indicated the probability of complete recovery of dichotomised prognostic factors, comparing the prognostically better value (for instance, an HB scale value lower than the median) in reference to the prognostically worse value (eg, an HB scale value higher than the median). In the first Cox model, the different subjective and clinical grading systems were compared. In the second model, different prognostic motor function and non-motor function tests were compared concerning their value to prognosticate the time course of recovery. In the third model, the HB scale values were added to the second model.

Results

Patients’ and disease characteristics

Two hundred and fifty-nine (259) patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria and constituted the database for this study. Patients’ characteristics are given in table 1. The median age was 53 years. The gender ratio was balanced (52.5% female and 47.5% male patients). There was no significant side predominance (56% left and 44% right side). The predominant origin was idiopathic (59%) and traumatic (21%). Each other origin represented <10% of cases. The median duration between the onset of palsy and admission to the hospital was 6 days. Fifty-eight percent (58%), 74% and 82% of patients presented within 7, 14 and 21 days after the onset of palsy. About half of the patients had an incomplete palsy (49%) and complete palsy (51%) at baseline. The median score on the HB scale at baseline was III. The median Stennert indexes at rest and during voluntary activity at baseline were 2 and 5, respectively.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics (n=259)

| Parameter | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 136 (53) |

| Male | 123 (47) |

| Affected side | |

| Left | 144 (56) |

| Right | 115 (44) |

| Aetiology | |

| Idiopathic | 152 (59) |

| Herpes zoster oticus | 22 (9) |

| Borreliosis | 15 (6) |

| Otogenic | 8 (3) |

| Traumatic | 55 (21) |

| Miscellaneous | 7 (3) |

| Severity at baseline | |

| Complete palsy | 132 (51) |

| Incomplete palsy | 127 (49) |

| House-Brackmann scale at baseline | |

| I | 0 (0) |

| II | 66 (25) |

| III | 75 (29) |

| IV | 82 (32) |

| V | 22 (9) |

| VI | 14 (6) |

| Median, range | |

| Age (years) | 53, 4–91 |

| Interval onset to diagnostics (days) | 6, 0–113 |

| House-Brackmann scale, baseline | 3, 2–6 |

| Stennert index at rest, baseline | 2, 0–4 |

| Stennert index in motion, baseline | 5, 0.6 |

| Stennert index, total, baseline | 6, 1–10 |

Serology

A combination of serology and/or CSF diagnostics confirmed Lyme disease in 15 of 15 cases with clinical suspicion. Thereby, the serological IgM immunoblot was positive in 15 of 15 cases and CSF in 7 of 15 cases. In 2 of the 22 patients with positive serology of acute VZV infection, in particular reinfection, CSF was also positive for VZV infection. Two other patients with acute VZV infection were at the same time positive for acute HSV infection. An isolated acute HSV infection was not seen. No patient showed serological signs for acute CMV or TBEV infection.

Electrodiagnostic facial motor function tests

The median interval between the onset of palsy and first EMG was 6 days (range 0–113 days). Hundred and fifty-three (153) patients received a second EMG after a median time of 33 days (range 4–292 days). Sixty-five (65) patients were scheduled for a third EMG after a median time of 98 days (range 17–742 days). During the first EMG examination, 88% of patients had no pathological spontaneous activity in the facial muscles ipsilateral to the palsy side and 12% showed such spontaneous activities. Sixty-nine percent (69%) had voluntary activity with more than single fibre activity and 31% had single fibre or no voluntary activity. The second EMG revealed no pathological spontaneous activity in 88% and such activity in 12% of cases. Eightly-nine percent (89%) had voluntary activity with more than single fibre activity and 11% had single fibre or no voluntary activity. Finally, the third EMG revealed no pathological spontaneous activity in 80% and such activity in 20% of cases. Seventy-four percent (74%) had voluntary activity with more than single fibre activity and 26% had single fibre or no voluntary activity. Overall, accounting for all EMG examinations, 80% of patients never had pathological spontaneous activity and 20% presented pathological spontaneous activity. ENG showed normal results in 24% and a prolonged latency or peak-to-peak amplitude loss in 76% of cases. A total of 20% of patients had normal R1 and R2 responses during BR and 80% had decreased or no R1 and/or R2 peaks.

Facial non-motor function tests and adjuvant diagnostics

At baseline, ipsilateral stapedius reflexes were lost in 66% and preserved in 34% of patients. The ipsilateral Schirmer test was pathological in 27% and normal in 73% of cases. Normal caloric stimulation was seen in 87% of cases and reduced/lost in 13%. Ipsilateral taste function was completely lost in 28% and preserved in 73% of AFP patients.

Prognostication of the time course of complete recovery of the facial motor function

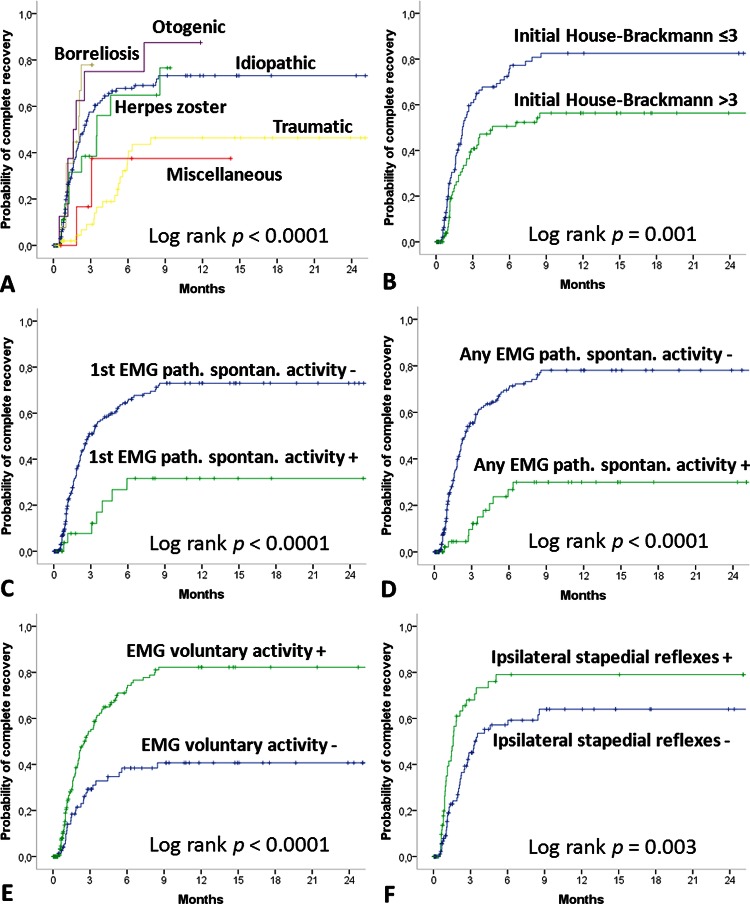

After a follow-up time of 5.6±9.8 months (median 1.9 months), 133 patients (51%) achieved an incomplete or no recovery and 126 patients (49%) showed a complete recovery. At 6 and 9 months after the onset, the complete recovery rate was 61% and 68%, respectively (table 2). The aetiology had significant influence on the recovery rate (table 3; p=0.023). Otogenic cases showed the best recovery rate, and traumatic cases the worst. The median recovery time for all patients was 3.5 months (95% CI 2.2 to 4.7). The time interval between the onset of AFP and diagnostics and the start of treatment was important. Patients presenting within 5 days after onset had a significantly shorter median recovery time than patients with a longer interval (p<0.0001). The influence of all patients’ and disease characteristics on the recovery time is summarised in table 4 and shown in figure 1. Gender, age and affected side had no influence on the median time of recovery (all p>0.05). Aetiology had prognostic influence (p<0.0001): patients with an otogenic origin had the fastest median recovery time; patients with zoster oticus had the longest median recovery time. The more severe the degree of peripheral facial palsy, the longer was the recovery time, no matter if it was measured clinically (p=0.004), or by the HB scale (p=0.001) or the Stennert index (p=0.015). Concerning the electrophysiological motor function tests, the detection of pathological spontaneous activity in the first EMG or any EMG, severe loss of voluntary EMG activity, and a pathological ENG result were significantly predictive of a worse probability of recovery (p<0.0001,< 0.0001, < 0.001 and 0.008, respectively). Pathological BR responses were not predictive (p=0.159). From the non-motor function test, only loss of stapedius reflexes was of significant prognostic value (p=0.003), whereas the Schirmer test, taste function test and vestibular caloric test were not helpful (p=0.119; p=0.060 and p=0.805).

Table 2.

Facial nerve grading at admission and at last examination during follow-up (n=259)

| First evaluation | Last evaluation | |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Number of patients (%) | Number of patients (%) |

| House-Brackmann scale | ||

| I | 0 (0) | 126 (49) |

| II | 66 (25) | 63 (24) |

| III | 75 (29) | 39 (15) |

| IV | 82 (32) | 22 (12) |

| V | 22 (9) | 7 (3) |

| VI | 14 (6) | 2 (1) |

| Median, range | ||

| Stennert index at rest | 2, 0–4 | 0, 0–4 |

| Stennert index in motion | 5, 0.6 | 1, (0–6) |

| Stennert index, total | 6, 1–10 | 1, 0–10 |

Table 3.

Influence of the aetiology on the complete recovery rate

| Aetiology | No recovery or incomplete recovery | Complete recovery | Absolute recovery rate (%) | Probability* of recovery at |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months (%) | 9 months (%) | ||||

| Idiopathic | 71 | 81 | 53 | 68 | 73 |

| Herpes zoster oticus | 12 | 10 | 46 | 65 | 77 |

| Borreliosis | 7 | 8 | 53 | 78 | 78 |

| Otogenic | 1 | 7 | 88 | 65 | 87 |

| Traumatic | 37 | 18 | 33 | 38 | 46 |

| Miscellaneous | 5 | 2 | 29 | 37 | 37 |

| Sum | 133 | 126 | 49 | 61 | 68 |

*Owing to the Kaplan-Meier calculation.

Table 4.

Influence of patients’ and diagnostic results on the recovery time

| Parameter | Median recovery time (months) | 95% CI (months) | Log rank test p value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.298 | ||

| Female | 3.5 | 1.7 to 5.3 | |

| Male | 3.3 | 1.4 to 5.1 | |

| Side | 0.103 | ||

| Right | 4.4 | 2.5 to 6.4 | |

| Left | 3.3 | 2.2 to 4.5 | |

| Age (median) | 0.763 | ||

| <53 years | 3.6 | 2.3 to 4.8 | |

| ≥53 years | 3.3 | 0.8 to 5.9 | |

| Aetiology | <0.0001 | ||

| Idiopathic | 2.5 | 1.9 to 3.1 | |

| Herpes zoster | 3.5 | 1.6 to 5.4 | |

| Borreliosis | 2.0 | 0.8 to 3.3 | |

| Otogenic | 1.6 | 0.7 to 2.5 | |

| Traumatic | NA | ||

| Miscellaneous | NA | ||

| Interval onset to diagnostics (median) | <0.0001 | ||

| <6 days | 2.1 | 1.6 to 2.7 | |

| ≥6 days | 6.5 | 3.5 to 9.6 | |

| Severity at baseline | 0.004 | ||

| Incomplete palsy | 2.5 | 1.9 to 3.1 | |

| Complete palsy | 5.1 | 0.5 to 10.0 | |

| House-Brackmann scale (median) | 0.001 | ||

| ≤3 | 2.2 | 1.6 to 2.7 | |

| >3 | 4.6 | 0.2 to 9.0 | |

| Stennert index, at rest (median) | 0.002 | ||

| <2 | 2.5 | 1.9 to 3.1 | |

| >2 | 5.7 | 2.2 to 4.5 | |

| Stennert index, in motion (median) | 0.004 | ||

| <5 | 2.5 | 1.9 to 3.1 | |

| >5 | 5.7 | 0.5 to 9.7 | |

| Stennert index, total (median) | 0.015 | ||

| <6 | 2.7 | 2.0 to 3.3 | |

| ≥6 | 4.0 | 1.8 to 6.2 | |

| First EMG; pathological spontaneous activity | <0.0001 | ||

| No | 2.8 | 2.1 to 3.6 | |

| Yes | NA | ||

| First EMG; voluntary activity | <0.0001 | ||

| No | NA | 2.4 to 3.7 | |

| Yes | 3.1 | ||

| Pathological spontaneous activity in any EMG | <0.0001 | ||

| No | NA | ||

| Yes | 2.5 | 2.0 to 3.0 | |

| ENG ipsilateral normal | 0.008 | ||

| No | 6.5 | 2.9 to 10.1 | |

| Yes | 1.9 | 1.9 to 2.5 | |

| Blink reflex ipsilateral | 0.159 | ||

| No | 2.5 | 1.7 to 3.3 | |

| Yes | 1.8 | 0.4 to 3.3 | |

| Schirmer test normal | 0.119 | ||

| No | 3.5 | 0.6 to 9.8 | |

| Yes | 2.2 | 1.6 to 2.7 | |

| Stapedius reflex ipsilateral | 0.003 | ||

| No | 3.3 | 2.0 to 4.6 | |

| Yes | 1.6 | 1.3 to 1.9 | |

| Taste function normal | 0.060 | ||

| No | 4.1 | 0.1 to 8.2 | |

| Yes | 2.5 | 1.8 to 3.2 | |

| Vestibular function normal | 0.805 | ||

| No | 3.5 | 1.0 to 6.0 | |

| Yes | 2.5 | 1.7 to 3.3 |

*Significant p values in italics.

NA, not applicable, because the overall probability to recovery was less than 0.5 in this subgroup.

EMG, electromyography; ENG, electroneurography.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves of the probability of complete recovery from facial palsy. Prognostic influence of (A) aetiology, (B) House-Brackmann scale at baseline, (C) evaluation for pathological spontaneous activity during first EMG, (D) evaluation for pathological spontaneous activity during any EMG, (E) evaluation for loss of voluntary activity during first EMG and (F) stapedius reflex testing.

In the multivariate Cox model with complete recovery as the end point, including the parameters aetiology, interval between onset and admission to the hospital, clinical incomplete/complete paresis, Stennert index, and House-Brackmann (HB) scale in a first block, only the time interval and the HB scale were significant independent prognostic factors (table 5). Including the motor and non-motor functional tests, EMG with evaluation for pathological spontaneous activity, EMG with evaluation for voluntary activity, ENG and stapedius reflex testing into the second model, EMG with evaluation for pathological spontaneous activity, ENG and stapedius reflex testing remained independent prognostic factors. Finally, in the third model, the time interval and HB scale were added to the second model. The result was that EMG with evaluation for pathological spontaneous activity and stapedius reflex testing continued to be independent prognostic factors for the prognosis of complete recovery from peripheral AFP.

Table 5.

Multivariate Cox regression analyses on independent diagnostic and prognostic factors on the recovery time

| Parameter | p Value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||||

| Aetiology | ||||

| Idiopathic | 0.473 | 2.070 | 0.284 | 15.084 |

| Zoster oticus | 0.473 | 2.138 | 0.269 | 16.986 |

| Borreliosis | 0.294 | 3.091 | 0.375 | 25.453 |

| Otogenic | 0.371 | 2.642 | 0.315 | 22.159 |

| Traumatic | 0.690 | 0.658 | 0.084 | 5.157 |

| Miscellaneous* | 1 | |||

| Interval onset to admission <median | 0.035 | 1.618 | 1.035 | 2.529 |

| Incomplete paresis | 0.796 | 1.113 | 0.494 | 2.511 |

| Stennert index, total, <median | 0.887 | 0.950 | 0.469 | 1.923 |

| House-Brackmann scale <median | 0.039 | 1.868 | 1.031 | 3.385 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| EMG, no pathological spontaneous activity | 0.015 | 4.545 | 1.336 | 15.466 |

| EMG, voluntary activity | 0.253 | 3.268 | 0.429 | 25.0 |

| ENG normal | 0.007 | 3.425 | 1.395 | 8.403 |

| Stapedius reflex normal | 0.003 | 2.660 | 1.402 | 5.050 |

| Model 3 | ||||

| Interval onset to admission <median | 0.436 | 1.451 | 0.569 | 3.702 |

| House-Brackmann scale <median | 0.151 | 1.679 | 0.828 | 3.406 |

| EMG, no pathological spontaneous activity | 0.015 | 4.915 | 1.357 | 17.806 |

| EMG, voluntary activity | 0.451 | 0.440 | 0.052 | 3.725 |

| ENG normal | 0.162 | 2.096 | 0.743 | 5.917 |

| Stapedius reflex normal | 0.009 | 2.801 | 1.297 | 6.024 |

Significant p values are shown in italics.

EMG, electromyography; ENG, electroneurography.

Discussion

We analysed 259 patients presenting with AFP treated with a standardised diagnostics and therapy protocol. Interested in predictors of the time course of recovery and prognosis, we focused not only on clinical data as did several previous studies, but also included parameters of a comprehensive diagnostic programme in the univariate and multivariate analyses. Needle EMG without signs of pathological spontaneous activity and a positive ipsilateral stapedius reflex were the most powerful, objective and independent predictors for faster recovery.

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

Owing to the fact that only those patients were included who received an electrophysiological examination within 120 days after onset, some polytrauma cases with AFP were excluded (data not shown). Therefore, traumatic cases and, related to this fact, male patients might be underrepresented in the present study. For some subgroups of aetiologies, only a few patients were included; for instance, just eight patients with an otogenic origin were included. Therefore, only limited conclusions can be drawn for these small subgroups. Furthermore, at baseline, a higher rate of complete palsies (overall, 51%; Bell's palsy, 54%) in the study sample is obvious in comparison with previous retrospective studies,7 10 and also higher than in recent prospective trials evaluating the efficacy of prednisolone and other drugs for Bell's palsy treatment, reaching values of less than 30–40%.3 4 The reason might be that in contrast to the cited studies using outpatient settings, we only included patients admitted to the hospital. The probability that less severe cases are referred to the hospital might be lower because these patients are primarily treated by practitioners in private practice.

There was a higher proportion of patients with complete palsy, which had a direct impact on the outcome because of the worse outcome and longer time of recovery, than patients with incomplete palsy.10 Moreover, although all patients received standardised prednisolone therapy according to actual guidelines, the treatment was given in a clinical routine setting. The two largest randomised trials on Bell's palsy started treatment 72 h after onset.3 5 In the present study, only 93 patients (36%) started the treatment within 72 h. Finally, the recovery rates in acute facial palsy studies are substantially affected by the choice of analysis method and definition of recovery.17 We used electromyography in the follow-up of the patients. This might be a more precise method than to perform only a clinical evaluation. These four factors already make it plausible why the recovery rate for all patients (68%) and Bell’s palsy cases (73%) were lower than those reported from recent prospective clinical drug trials for Bell's palsy (94–96%3 4). The sole exception is the clinical trial of Engström et al5 giving an outcome for prednisolone therapy of 72% (patients with a Sunnybrook score of 100) or 78% (HB I) for complete recovery after 12 months.17 In Engström's study, the proportions of complete palsy cases seem to be in the range of the present study (number not given in the publication, but the median HB at onset was IV in the Swedish study vs III½ in the present study). Besides, Engström's study is the only prospective trial calculating the probability of recovery by the Kaplan-Meier curves. The median time to complete recovery for the prednisolone group in Engström's study was the same as in the present study for Bell's palsy, 75 days.

Meaning of the study and possible explanations

The present and other electrophysiological studies suggest that the severity of the facial nerve lesion (the aetiology only has an indirect effect) with anatomic disruption of the facial nerve axons, that is, a degenerative lesion with axonotmesis and/or neurotmesis, is the primary reason for incomplete recovery.11 18 Future clinical trials with intent to improve the outcome of AFP and especially for Bell's palsy, for instance by a multidrug approach, should focus on this risk group. Recent multicentre trials on Bell's palsy did not account for this important issue.3 5

Candidates for a diagnostic selection test would be 2–3 tests that turned out to be most robust to prognosticate a worse outcome and prolonged recovery: evaluation of (1) EMG with pathological spontaneous activity, (2) unilateral stapedius reflex answers and (3) ENG responses. Spontaneous EMG activity in the form of positive sharp waves and fibrillation potentials are well accepted as precise signs of axonal degeneration.19 A disadvantage is that pathological spontaneous activity occurs not before 10–14 days after onset of the lesion, which might be too late for an early treatment decision. The presented results advise combining the EMG with an ENG examination and repeating the EMG when reaching the optimal time window.11 20 Interestingly, the stapedius reflex test was the other strong prognosticator. The stapedius reflex was part of the topodiagnostic tests for AFP in the era before CT and MRI came up.21 Because of a low predictive value to indicate the site of lesion, in the era of modern imaging the stapedius reflex slipped out of focus. The stapedius reflex was also proposed to be of prognostic value in several retrospective analyses but had never been tested so far in a prospective study.22 A subpopulation of the stapedius motoneurons forms the ipsilateral stapedial branch of the facial nerve and contracts the ipsilateral stapedius muscle.23 Why the axons of the stapedial branch seem to be very sensible to a peripheral facial nerve lesion proximal to the anatomical leaving of the nerve within the temporal bone is unknown. We recommend using the stapedius test together with electrophysiological tests because it has two disadvantages: it has no significance in patients with synchronous ipsilateral middle ear disease and in case of definite facial nerve lesion far distal to the branching of the stapedial nerve, which could be present especially in traumatic AFP.

Conclusion

Although it should be a common practice to perform EMG and ENG in patients with AFP and a least practice to perform the stapedius test, we advocate, based on the findings of this study, to more routinely perform EMG, ENG and stapedius tests in patients with AFP. These tests should help, especially also in clinical trials, identify patients with lower probability of complete recovery and longer recovery time with the aim to order adjuvant drug and also surgical treatment at early stage.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Karolin Weigel and Martin Pohlmann for their support in collecting the study data.

Footnotes

Contributors: OGL and OWW developed the idea for the study. OGL and OWW made all drafts of the manuscript. All authors analysed and interpreted the data. GFV, CK and MF revised the final manuscript. OGL is the guarantor.

Funding: This work was supported by BMBF (01GZ0709) and the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research Jena.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the local ethics board at the University Hospital Jena in Germany.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Gilden DH. Clinical practice. Bell's Palsy. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1323–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heckmann JG, Lang C, Glocker FX, et al. The new S2k AWMF guideline for the treatment of Bell's palsy in commented short form. Laryngorhinootologie 2012;91:686–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan FM, Swan IR, Donnan PT, et al. Early treatment with prednisolone or acyclovir in Bell's palsy. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1598–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hato N, Yamada H, Kohno H, et al. Valacyclovir and prednisolone treatment for Bell's palsy: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Otol Neurotol 2007;28:408–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engstrom M, Berg T, Stjernquist-Desatnik A, et al. Prednisolone and valaciclovir in Bell's palsy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol 2008;7:993–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peitersen E. Bell's palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2002:4–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ljostad U, Okstad S, Topstad T, et al. Acute peripheral facial palsy in adults. J Neurol 2005;252:672–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiu WW, Yin SS, Stucker FJ, et al. Time course of Bell palsy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996;122:967–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanaya K, Ushio M, Kondo K, et al. Recovery of facial movement and facial synkinesis in Bell's palsy patients. Otol Neurotol 2009;30:640–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linder TE, Abdelkafy W, Cavero-Vanek S. The management of peripheral facial nerve palsy: “paresis” versus "paralysis" and sources of ambiguity in study designs. Otol Neurotol 2010;31:319–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grosheva M, Wittekindt C, Guntinas-Lichius O. Prognostic value of electroneurography and electromyography in facial palsy. Laryngoscope 2008;118:394–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1985;93:146–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stennert E, Limberg CH, Frentrup KP. An index for paresis and defective healing—an easily applied method for objectively determining therapeutic results in facial paresis (author's transl). HNO 1977;25:238–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guntinas-Lichius O, Straesser A, Streppel M. Quality of life after facial nerve repair. Laryngoscope 2007;117:421–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valls-Sole J. Electrodiagnostic studies of the facial nerve in peripheral facial palsy and hemifacial spasm. Muscle Nerve 2007;36:14–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gudziol H, Hummel T. Normative values for the assessment of gustatory function using liquid tastants. Acta Otolaryngol 2007;127:658–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berg T, Marsk E, Engstrom M, et al. The effect of study design and analysis methods on recovery rates in Bell's palsy. Laryngoscope 2009;119:2046–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seddon H. Three types of nerve injury. Brain 1943;66:237–88 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stalberg E. Invited review: electrodiagnostic assessment and monitoring of motor unit changes in disease. Muscle Nerve 1991;14:293–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee DH, Chae SY, Park YS, et al. Prognostic value of electroneurography in Bell's palsy and Ramsay-Hunt's syndrome. Clin Otolaryngol 2006;31:144–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guntinas-Lichius O. The facial nerve in the presence of a head and neck neoplasm: assessment and outcome after surgical management. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004;12:133–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosen G, Sellars SL. The stapedius reflex in idiopathic facial palsy. J Laryngol Otol 1980;94:1017–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukerji S, Windsor AM, Lee DJ. Auditory brainstem circuits that mediate the middle ear muscle reflex. Trends Amplif 2010;14:170–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.