Abstract

A previously fit and well 44-year-old gentleman was admitted with a 3-week history of parotid swelling, malaise and feeling generally unwell. His only medical history was α-thalassaemia trait. Initial ear, nose and throat examination was unremarkable. Routine observations highlighted tachycardia, hypotension and a raised respiratory rate. Despite fluid resuscitation, his hypotension failed to resolve and he was admitted to intensive care for inotropic support. He was started on broad spectrum antibiotics and blood cultures isolated Lancefield group A Streptococcus. No obvious source of sepsis was identified. A CT scan from neck to pelvis highlighted a collection around the right tonsil, splenomegaly and widespread small volume lymphadenopathy. A right tonsillectomy, intraoral drainage of parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal abscesses and excision of an axillary lymph node were performed. With continued intravenous antibiotics and supportive measures, he recovered fully. Histology showed reactive lymphadenitis, but no cause of immunocompromise.

Background

Invasive streptococcal throat infections are a rare phenomenon in adults, but can have a high level of morbidity and mortality, particularly when associated with any underlying impairment of the immune system. Treatment includes securing the airway, systemic antibiotics and appropriate drainage of the abscess.

Here, we report a highly atypical presentation of a Streptococcal parapharyngeal abscess with retropharyngeal extension causing sepsis and multi-organ failure in a previously well man.

This case highlights the importance of prompt recognition, diagnosis and treatment in sepsis. Consideration of an unusual infective source and the possibility of undiagnosed immunocompromise must not be overlooked. We also briefly review the published literature looking at the aetiology and presenting features of deep neck space infections in adults.

Case presentation

A 44-year-old man of Hungarian origin was admitted via the accident and emergency department with a 3-week history of parotid swelling, tiredness and feeling generally unwell.

At the onset of symptoms, he presented to his general practitioner (GP) with a sore throat and bilateral parotid swelling and a diagnosis of mumps had been made. One of his work colleagues had recently reported similar symptoms which had fully resolved prior to the onset of our patient's illness. Three weeks later, at presentation to the accident and emergency department, the sore throat had resolved and he had unilateral, right-sided parotid swelling. His oral intake had been poor lately, but he had no problems swallowing. He subsequently developed right leg and knee pain and swelling which then spread into his other limbs.

His medical history was unremarkable other than α-thalassaemia trait and treatment by his GP for intermittent chest infections. He had no significant family history. He worked as a chef and had been in the UK for 7 years. He lived with his wife and child who had not been unwell recently and was an ex-smoker with a 15 pack-year history.

On examination, he looked flushed and lethargic, but sat upright, was normally orientated and conversant. His temperature was 38.2°C, blood pressure was 84/52 mm Hg, pulse 106 bpm, respiratory rate was 25/min and oxygen saturations were 100% on air.

There was a non-tender swelling over his right parotid gland, but no pus was expressed from Stenson's duct. The left parotid was normal on examination and both facial nerves were intact. The ears were full of cerumen, but otoscopy showed no evidence of infection.

There were no palpable lymph nodes in his neck and neck movements were not restricted or painful. His mouth opening was normal with an unremarkable oropharyngeal examination. There was no evidence of significant dental disease and he was not drooling.

Approximately 17 h after admission he deteriorated further, becoming more hypotensive, tachycardic and feeling worse. At this point, broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics were initiated. Despite intravenous antibiotics and fluid resuscitation, his clinical parameters failed to respond and he was transferred to the intensive care unit (ITU) for inotropic support.

Investigations

Routine blood tests on admission showed his C reactive protein to be raised at 344 mg/l, but white cell count and renal function were normal. Liver function tests (LFTs) were deranged. Serum albumin was 26 g/l and serum lactate 5.8 mmol/l.

His chest radiograph was clear and urinalysis showed 3+blood, 3+protein and nitrites but no white cells. Blood cultures from admission grew Lancefield Group A Streptococcus sensitive to penicillin. HIV screen was negative on two occasions.

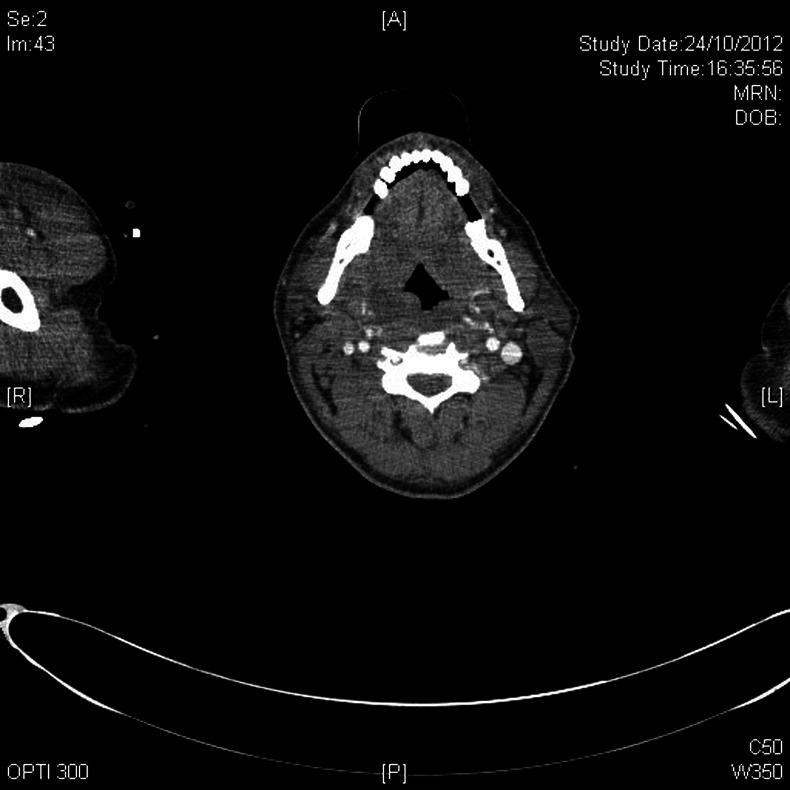

The day after ITU admission, a CT scan from neck to pelvis was performed to identify a source of infection. The scan showed significant subcutaneous oedema, pleural and pericardial effusions and widespread small volume lymphadenopathy indistinguishable from lymphoma. The right parotid gland displayed heterogeneous swelling, but there was no evidence of a collection. There were appearances of a low-attenuation collection around the right tonsil suggestive of an abscess (figure 1). The spleen was also enlarged with evidence of a localised splenic infarction.

Figure 1.

CT scan showing a possible collection around the right tonsil.

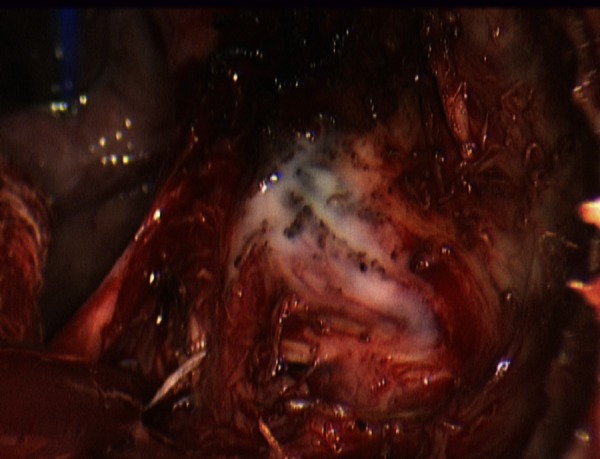

Flexible nasendoscopy showed a slight bulge on the right pharyngeal wall coated with dried secretions (figure 2). A bedside ultrasound scan of the neck performed the following day showed a 2–3 cm abscess in the deep lobe of the right parotid extending to the paraphayngeal space.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative image showing right posterior pharyngeal wall bulging in keeping with a retropharyngeal abscess.

Emergency right tonsillectomy, intraoral drainage of right parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal abscesses and left axillary node excision for histological analysis were performed on the same day.

Differential diagnosis

Common causes of sepsis were initially considered such as urine and lower respiratory tract infection. Mid-stream urine analysis was negative for infection and his chest x-ray was unremarkable. Viral illnesses were considered owing to the indolent progression of his illness, non-specific symptoms and deranged LFTs. Tests for viral hepatitis, Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus were performed, but were all negative. Mumps immunoglobulin M was also negative.

Endocarditis was suspected owing to the subacute onset of clinical symptoms and the presence of temperatures, fatigue, joint pains and muscle aches. However, no murmurs were present on chest auscultation and ECG performed in the ITU showed a small pericardial effusion only with no evidence of endocarditis.

Owing to his highly unusual presentation, an undiagnosed cause of immunocompromise was considered. HIV testing was negative and there was no evidence of diabetes mellitus. Underlying lymphoma was suspected by our haematology colleagues and excision of a lymph node for histology was performed upon their recommendation to rule out this possibility. This showed no evidence of lymphoma. A blood film showed a leukoerythroblastic anaemia with target cells consistent with sepsis on a background of α-thalassaemia trait.

Treatment

Empirical broad spectrum antibiotics were given shortly before admission to ITU. Intravenous clindamycin and meropenem were initiated on a specialist's advice and he was given a single dose of intravenous immunoglobulin upon ITU admission. Blood cultures grew Group A Streptococcus (GAS) and antibiotics were changed to benzylpenicillin and clindamycin postoperatively based on bacteriological sensitivities. Intravenous micafungin was added on day 9 owing to candida-positive blood cultures and stopped after 3 days. He got over his fever on day 12 of admission and intravenous antibiotics were given for a total of 13 days.

The parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal abscesses were treated with rigid pharyngoscopy, intraoral drainage, right tonsillectomy and abscess cavity irrigation (figures 3 and 4). Electively, it was decided that the patient should be kept intubated postoperatively. As the patient improved, he was eventually extubated 9 days later. Intravenous fluid resuscitation, inotropic support and haemofiltration were performed while in intensive care. On day 14, he was transferred to the ward and was discharged from hospital 2 weeks later.

Figure 3.

Intraoperative image of retropharyngeal abscess drainage.

Figure 4.

Intraoperative drainage of a parapharyngeal abscess following tonsillectomy.

Outcome and follow-up

Histology of the excised tonsil revealed benign inflammatory changes. There was no recurrence of the infection and he was able to eat and drink normally.

The excised lymph node showed a reactive lymphadenitis with no evidence of malignancy.

The patient was reviewed in clinic 3 weeks after discharge and was doing well. He has subsequently been discharged from our care.

Discussion

The parapharyngeal space lies lateral to the pharynx, medial to the parotid gland and inferior to the skull base. It is shaped like an inverted pyramid and inferiorly is continuous with the retropharyngeal space. Parapharyngeal abscesses are thought to occur secondary to an upper respiratory tract infection and can cause life-threatening complications, either as a result of systemic sepsis or involvement of local anatomical structures. These include pseudoaneurysm formation of the carotid artery, jugular vein thrombosis or extension into the retropharyngeal or prevertebral space. Retropharyngeal extension is one of the most feared complications, as it can result in airway compromise or descending infection into the mediastinum.

Deep neck space infections are unusual in adults. In children, the frequency of middle ear and throat infections increases the likelihood of spread to the retropharyngeal space, but the reduced infective load in adults makes such infections a rarity in the absence of penetrating pharyngeal injury or immunocompromise.1

This was a highly atypical case of a deep neck space infection. It most likely developed as a result of a Streptococcal pharyngitis though this occurred weeks before his presentation to hospital, at which point he had no throat pain, dysphagia or neck swelling. Parapharyngeal abscesses classically cause lateral pharyngeal wall swelling which our patient indeed had though this was not visible on oropharyngeal examination and was causing no discomfort to the patient. In a review of parapharyngeal abscesses treated between 2000 and 2007 in a hospital in Northern France, Page and colleagues describe the presenting features, bacteriology and treatment of 16 cases of parapharyngeal abscess in adults and children. All patients presented with dysphagia and sore throat.2 Perhaps the only presenting symptom suggesting pathology in the pharynx in our case was unilateral non-tender parotid swelling (which was later confirmed to be owing to the abscess deep to the parotid gland) which has hitherto not been reported in the literature as a presenting symptom of this condition.

It is of importance that no underlying cause of immunocompromise could be elucidated in this patient. In previous reviews, there has been a clear association between immunosuppression, the incidence of invasive GAS infection and mortality. The condition also arises much more commonly in the elderly.3 4 Our patient was 44 years-old with no known cause of immunosuppression. Ongoing research in to the role of virulence factors in the pathogenesis of invasive GAS may shed light on the causes of life-threatening infection in previously well individuals.5

Furthermore, in a study of recorded cases of invasive GAS infections that occurred between 2000 and 2004 in the USA, the authors demonstrated that the most common source of invasive GAS infection was from skin or soft tissue infections. Streptococcal pharyngitis was rarely identified as a source of invasive infection and it is of note that the next most likely finding was that the source of sepsis would not be identified.3 In light of our experience with this case, it is the opinion of the authors that imaging of the pharynx is recommended in cases of invasive GAS when the source cannot be identified.

Our patient had a delayed diagnosis of sepsis. This has been well associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Streptococcal septic shock syndrome carries a mortality risk of approximately 36% and this instructive case was a reminder for the authors of how profoundly septic patients can look misleadingly well. Early fluid resuscitation and intravenous antibiotics are essential in the case of Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, with the Irish Health Protection Surveillance Centre recommending intravenous benzylpenicillin, flucloxacillin and clindamycin as the empirical regime of choice until microbiological results are available.4 Intravenous immunoglobulin is also often used in this condition as there is some evidence to suggest that it may incur a survival benefit.6

Learning points.

Deep neck space infections can present with little in the way of local symptoms.

Consider an undiagnosed streptococcal neck abscess in cases of Group A streptococcal septicaemia with no known source.

Do not be misled by a well-looking patient. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome has a high-death rate and requires prompt treatment of sepsis and surgical intervention if indicated.

Footnotes

Contributors: HR collected data from the patient's medical notes, drafted and revised the paper. He is guarantor. EI drafted the paper. CW drafted and revised the paper. GB revised the paper.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Brito-Mutunayagam S, Chew YK, Sivakumar K, et al. Parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal abscess: anatomical complexity and etiology. Med J Malaysia 2007;2013:413–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Page C, Biet A, Zaatar R, et al. Parapharyngeal abscess: diagnosis and treatment. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2008;2013:681–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Loughlin RE, Roberson A, Cieslak PR, et al. The epidemiology of invasive group A Streptococcal infection and potential vaccine implications: United States, 2000–2004. Clin Infect Dis 2007;2013:853–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Management of Invasive Group A Streptococcal Infections in Ireland Health Protection Surveillance Centre. http://www.hpsc.ie/hpsc/AboutHPSC/ScientificCommittees/Publications/File,2080,en.pdf (accessed 22 Apr 2013).

- 5.Cunningham MW. Pathogenesis of group A Streptococcal infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000;2013:470–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raithatha AH, Bryden DC. Use of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in the treatment of septic shock, in particular severe invasive group A Streptococcal disease. Indian J Crit Care Med 2012;2013:37–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]