Abstract

There is no formal association between premature coronary artery disease (CAD) and Prader-Willi syndrome despite its association with hyperlipidaemia, diabetes mellitus and hypertension. A 36-year-old man with Prader-Willi syndrome presented with acute breathlessness. Inflammatory markers were borderline elevated and chest radiography demonstrated unilateral diffuse alveolar shadowing. Bronchopneumonia was diagnosed and despite treatment with multiple courses of antimicrobial therapy, there was minimal symptomatic and radiographical improvement. A diagnosis of unilateral pulmonary oedema was suspected. Echocardiography was non-diagnostic due to body habitus and coronary angiography was deemed inappropriate due to uncertainty in diagnosis, invasiveness and pre-existing chronic kidney disease. Therefore, cardiac magnetic resonance was performed, confirming severe triple-vessel CAD. This case demonstrates a presentation of heart failure with unilateral chest radiograph changes in a young patient with Prader-Willi syndrome and severe premature CAD detected by multiparametric cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.

Background

There have only been two reported cases of premature coronary artery disease (CAD) in Prader-Willi syndrome in the literature.1 2 This is despite its association with obesity, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Establishing a diagnosis of coronary artery disease in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome poses potential diagnostic challenges owing to the increased likelihood of non-diagnostic first-line investigations due to body habitus, including echocardiography, exercise ECG testing and nuclear myocardial perfusion imaging. In addition, exertional breathlessness is common in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome due to obesity, sleep apnoea syndrome and physical deconditioning, which can mask ‘angina equivalent’ (angina manifesting as breathlessness).

This case brings together cardiology, respiratory medicine, endocrinology, radiology and acute medicine.

Case presentation

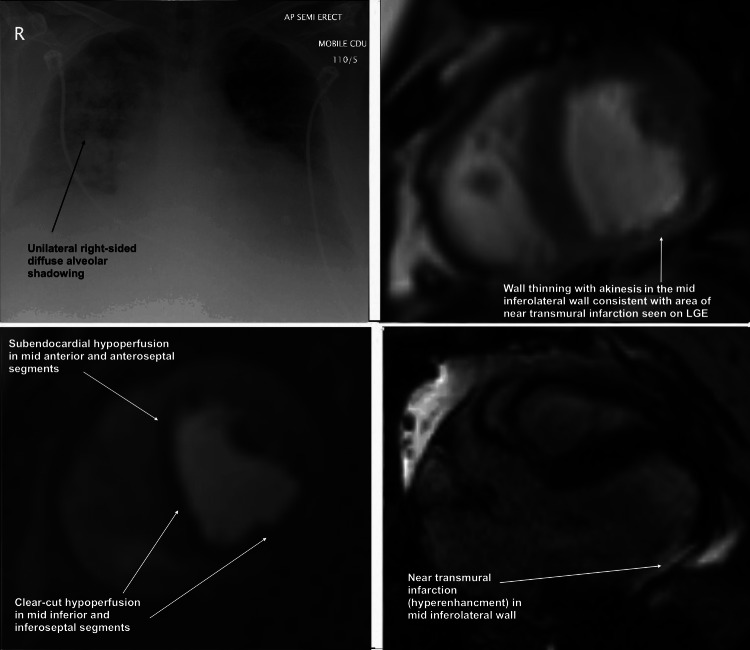

A 36-year-old man was admitted with a 1 week history of breathlessness and peripheral oedema, accompanied by pink sputum. Previous medical history included Prader-Willi syndrome, obesity (body mass index 48 kg/m2), stage 3 chronic kidney disease (CKD), obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS), hyperlipidaemia and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. On admission he was hypoxic (oxygen saturation 91% on air), tachycardic (heart rate 108/min), tachypnoeic (respiratory rate 26/min) and normothermic (37°C). There was pitting oedema of the lower legs. Auscultation revealed unilateral crepitations throughout the right lung. Inflammatory markers were borderline elevated (C reactive protein 12 mg/l, leucocyte count 10×103/l) and chest radiography demonstrated unilateral right-sided diffuse alveolar shadowing and cardiomegaly (figure 1A). A 12-lead ECG demonstrated sinus tachycardia with no changes consistent with ischaemia or right ventricular strain. Bronchopneumonia was diagnosed and he was started on coamoxiclav, doxycycline and oral furosemide. He presented 1 month later with an almost identical admission and was managed similarly. Two months later, he was readmitted with similar clinical and chest radiograph findings. The working diagnosis remained bronchopneumonia; however, due to the lack of response to tazocin and meropenem and persistent right-sided airspace shadowing, a differential diagnosis of heart failure was considered.

Figure 1.

(from top left, clockwise) (A) Unilateral right-sided shadowing seen on chest radiograph. (B) Cine image at mid-ventricular level showing wall thinning in area of akinesis and near transmural infarction in mid inferolateral wall. (C) First-pass adenosine stress perfusion cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) cine image at mid ventricular short-axis level demonstrating significant hypoperfusion (ischaemia) in right coronary artery and left anterior descending territories. (D) Late gadolinium enhancement CMR image in three-chamber long axis view demonstrating near transmural infarction in mid inferolateral wall.

Although CT of the chest may have helped clarify the nature of the pulmonary opacities, it was not performed. This was owing to the clinical picture that was increasingly consistent with pulmonary oedema (positive response to frusemide and nitrates, lack of response to antimicrobials, alveolar CXR shadowing) and the risk of contrast nephropathy due to the patient's worsening pre-existing stage 3 CKD. Echocardiography was non-diagnostic owing to poor acoustic windows due to body habitus. Alternative cardiac imaging was indicated and given the patient's obesity, cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) was performed utilising the hospital's wide-bore 3-Tesla MRI scanner. CMR was chosen in this case as it allows a comprehensive non-invasive assessment of left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) structure and function, pulmonary hypertension and ischaemia without the risk of contrast nephropathy. Coronary angiography was deemed an inappropriate initial strategy owing to uncertainty in diagnosis, its invasiveness and the potential for contrast nephropathy.

Investigations

CMR was performed with adenosine stress and late gadolinium enhancement imaging for the detection of ischaemia and infarction, respectively. Wall-motion assessment demonstrated akinesis in the mid-inferolateral segment, hypokinesis in the inferoseptal and inferior regions with a small near transmural infarction on late gadolinium imaging (figure 2A–C). First-pass stress perfusion demonstrated reversible perfusion defects in the inferoseptal and inferior walls and subendocardial defect in the basal and mid anterior and anteroseptal regions, strongly suggestive of ischaemia in the right coronary artery (RCA) and left anterior descending artery (LAD) territories, respectively (figure 1B–D). The findings suggested triple-vessel CAD. LV systolic function was mildly impaired (LV ejection fraction 47%). All three coronary artery territories were considered viable since only 1 of 16 segments was transmurally infarcted. The RV was mildly dilated with mild systolic impairment, consistent with longstanding OSAS and obesity and with previous echocardiography (RV end-diastolic volume 95 ml/m2, RV ejection fraction 39%).

Figure 2.

(left to right) (A) Coronary angiogram image of left coronary system demonstrating significant left anterior descending (LAD) and left-circumflex artery (LCX) disease (lesion labelled 1: severe stenosis in mid LAD, 2: occluded distal LCX). (B) Coronary angiogram image demonstrating significant right coronary artery (RCA) disease at multiple sites (lesion labelled 3: severe proximal RCA stenosis, 4: moderate mid RCA stenosis, 5: three severe stenoses in distal RCA).

Inpatient coronary angiography demonstrated severe triple-vessel CAD with an occluded distal left-circumflex artery consistent with the area of infarction on CMR imaging, and severe LAD and RCA stenoses (figure 2). After discussing treatment options, outpatient percutaneous intervention to the LAD and RCA was planned.

Differential diagnosis

A patient presenting with a 1 week history of breathlessnes, productive cough and unilateral chest radiograph shadowing is likely to have a bronchopneumonia. However, in our patient the inflammatory markers were borderline elevated on each admission and there was minimal symptomatic and radiographic improvement with multiple courses of antimicrobials. In view of this and the patient's multiple risk factors for CAD (obesity, diabetes mellitus, CKD, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia), we considered a differential diagnosis of unilateral pulmonary oedema. This was supported by the significant clinical improvement after the commencement of high-dose loop-diuretics and oral nitrates.

Key differential diagnoses for recurrent pulmonary oedema in this patient included:

▸ Coronary artery disease

▸ LV dysfunction (systolic or diastolic)

▸ Severe valve disease

▸ Cardiomyopathy

▸ Critical renal artery stenosis (‘flash pulmonary oedema’) was very unlikely as previous renal ultrasound had confirmed normal sized kidneys

CMR imaging allowed a comprehensive, non-invasive and accurate assessment for all key differential diagnoses in our patient. The patient's pulmonary oedema was attributed to the combination of LV systolic and diastolic dysfunction and severe CAD.

Outcome and follow-up

Six months after the initial diagnosis, the patient has improved and has a low symptomatic burden (New York Heart Association Class 2 breathlessness, Canadian Cardiovascular Society Class 1 anginai) and is currently being managed on medical therapy (aspirin, clopidogrel, bisoprolol, ramipril, atorvastatin, furosemide, isosorbide mononitrate). A repeat chest radiograph has shown complete resolution of the right-sided diffuse alveolar shadowing. There has been a delay in percutaneous coronary intervention owing to two admissions with osteomyelitis of the foot, which have required prolonged antimicrobial therapy.

Discussion

This case provides several important learning points. First, LV failure can present as unilateral pulmonary oedema and this should be considered in patients with suspected pneumonitis resistant to antimicrobial therapy. Second, clinicians should be aware that severe premature coronary artery disease can occur in Prader-Willi syndrome or in others with multiple risk factors. Obesity plays a key role in Prader-Willi syndrome because of association with hyperlipidaemia, diabetes mellitus and hypertension.3 Our case is one of only three reported cases of premature coronary artery disease in Prader-Willi syndrome.1 2 Clinicians may see a marked increase in premature coronary artery disease in coming years owing to the dramatic rise in obesity and associated ‘epidemic’ of diabetes mellitus. Third, CMR is a highly versatile non-invasive imaging modality allowing accurate assessment of ventricular function, detection of small myocardial scars (infarcts and non-ischaemic fibrosis) and adenosine stress-perfusion has excellent diagnostic accuracy for the detection of CAD.4 CMR use in the UK is increasing exponentially and is now regarded as a first-line investigation in many institutions.5 CMR should be considered when alternative imaging modalities are likely to give non-diagnostic results. Limitations of CMR include contraindications in patients with certain metallic implants including pacemakers and defibrillators, claustrophobia and body size due to the narrow bore of most scanners. However, the latter is being addressed by MRI manufacturers and our platform accommodates patients of up to 250 kg without degradation of image quality.

This case demonstrates a presentation of heart failure with unilateral chest radiograph changes in a young patient with Prader-Willi syndrome and severe premature coronary artery disease detected by multiparametric CMR.

Learning points.

Clinicians should be aware that premature coronary artery disease can occur in Prader-Willi syndrome or in other young patients with multiple risk factors.

Left ventricular failure can present as unilateral pulmonary oedema and this should be considered in patients with suspected pneumonitis resistant to antimicrobial therapy.

Cardiac magnetic resonance is a highly versatile, increasingly available, non-invasive imaging modality with excellent diagnostic accuracy for detection of coronary artery disease.

Contributors: AJ and JNK wrote the manuscript. GM and AS critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors were involved the patient's care.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Class 1—Cardiac disease, but no symptoms and no limitation in ordinary physical activity, for example, shortness of breath when walking, climbing stairs, etc.

- Class 2—Mild symptoms (mild shortness of breath and/or angina) and slight limitation during ordinary activity.

- Class 3—Marked limitation in activity due to symptoms, even during less-than-ordinary activity, for example, walking short distances (20–100 m).

- Class 4—Severe limitation; symptoms even at rest; mostly bedbound patients.

- Class 1—Angina only during strenuous or prolonged physical activity.

- Class 2—Slight limitation, with angina only during vigorous physical activity.

- Class 3—Symptoms with everyday living activities, that is, moderate limitation.

- Class 4—Inability to perform any activity without angina or rest angina; severe limitation.

References

- 1.Page SR, Nussey SS, Haywood GA, et al. Premature coronary artery disease and the Prader-Willi syndrome. Postgrad Medl J 1990;2013:232–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamb AS, Johnson WM. Premature coronary atherosclerosis in a patient with the Prader-Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1987;2013:873–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler JV, Whittington JE, Holland AJ, et al. Prevalence of, and risk factors for, physical ill health in people with Prader-Willi syndrome: a population-based study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2002;2013:248–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenwood JP, Maredia N, Younger JF, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance and single-photon emission computed tomography for diagnosis of coronary heart disease (CE-MARC): a prospective trial. Lancet 2012;2013:453–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antony R, Daghem M, McCann GP, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance activity in the United Kingdom: a survey on behalf of the British Society of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2011;2013:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Criteria Committee of the New York Heart Association Nomenclature and criteria for diagnosis of diseases of the heart and blood vessels. Boston: Little Brown, 1964 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campeau L. Grading of angina pectoris. Circulation 1976;2013:522–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]