Abstract

A middle-aged female patient with diabetes was admitted with a right neck abscess. Ultrasound scan revealed a necrotic abscess suspicious of malignancy and biopsy showed evidence of chronic inflammation. In order to isolate the primary source of malignancy, we performed MRI and positron emission tomography scans but neither had conclusive results. Subsequently, we performed an incision and drainage of the mass in order to alleviate pressure symptoms. The ensuing histological examination revealed that the mass was caused by Lactococcus lactis cremoris. As such, the patient was treated with antibiotics and made a complete recovery. This report reinforces the scarce existing evidence that L lactis cremoris is a potential pathogen in adults. The case shows that atypical organisms should always be considered in the working diagnosis of an atypical neck abscess especially due to the rise in popularity of organic farming.

Background

Lactococcus lactis cremoris infection is commonly classified as ‘rare’ in humans. However, it is imperative that medical professionals are aware of the L lactis cremoris bacterium because it is present in unpasteurised dairy products, which are now common with the advent of organic farming. Indeed, to our knowledge, this is the 15th case of this pathogen causing clinically significant infection.

L lactis cremoris is a facultative anaerobic Gram-positive coccus.1 It was once classified as streptococcus and was transferred to the genus Lactococcus in 1985.1 It is a recognised commensal organism of mucocutaneous surfaces of cattle, and is occasionally isolated from human mucocutaneous surface.2 This organism is used as an additive in the process of making dairy products. L lactis cremoris is commonly considered to be non-pathogenic in immunocompetent adults. However, human infections have been noted affecting different systems in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised adults and children.3–5

Case presentation

A middle-aged female patient with diabetes presented with a 6 week history of enlarging mass at the right side of her neck. The patient described it as sudden onset, which was initially painful and had increased in size since its inception. She denied any other aero-digestive tract symptoms, dysphagia, change in voice or any weight loss. The patient was taking oral medications and insulin for her diabetes but admitted that her diabetes had not been well controlled. The patient was a non-smoker and rarely drunk alcohol.

On examination an oedematous and erythematous mass was noted in the right side of the neck, measuring 5–6 cm fixed involving level 2/3 and was distant from the thyroid. There were no visible oral lesions and flexible nasopharyngo-laryngoscopy revealed no mucosal lesions. No lymph nodes were palpable.

Investigations

Biochemical analyses demonstrated a mild leucocytosis and neutrophilia, white blood cell count 10.9×109/l, neutrophils 8.57×109/l. An acute phase response was not evident with C reactive protein 12 mg/l.

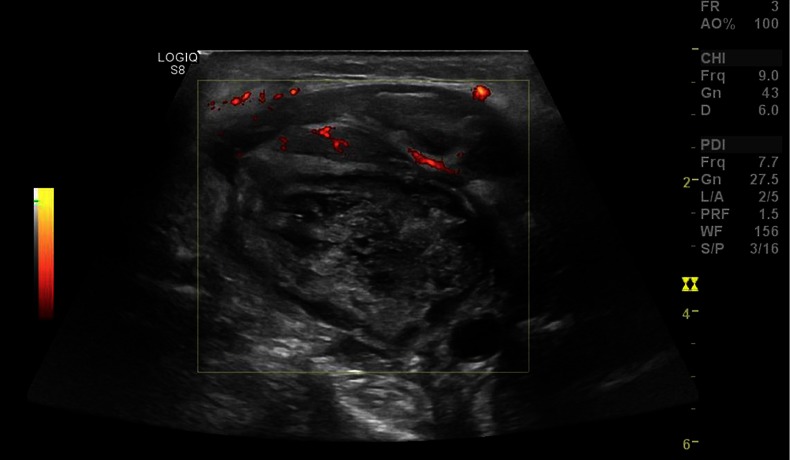

Due to the suspicious lesion and the fact that the patient had no systemic features of infection an ultrasound scan and fine needle aspirate cytology was requested to exclude malignancy. The ultrasound scan revealed a large heterogeneous necrotic mass measuring 4.7×4 cm involving level 2/3 of the neck (figure 1). There was evidence of an extracapsular spread, with involvement of the adjacent soft tissue and in particular the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The right carotid artery was metallized and circumferentially encased 180° by the necrotic mass. Fine needle aspiration, repeated twice, revealed features consistent with an underlying necrotic abscess. Epithelial cells were not identified. Appearances were highly suspicious for a necrotic metastatic lymph node.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound scan revealed a large heterogeneous necrotic mass.

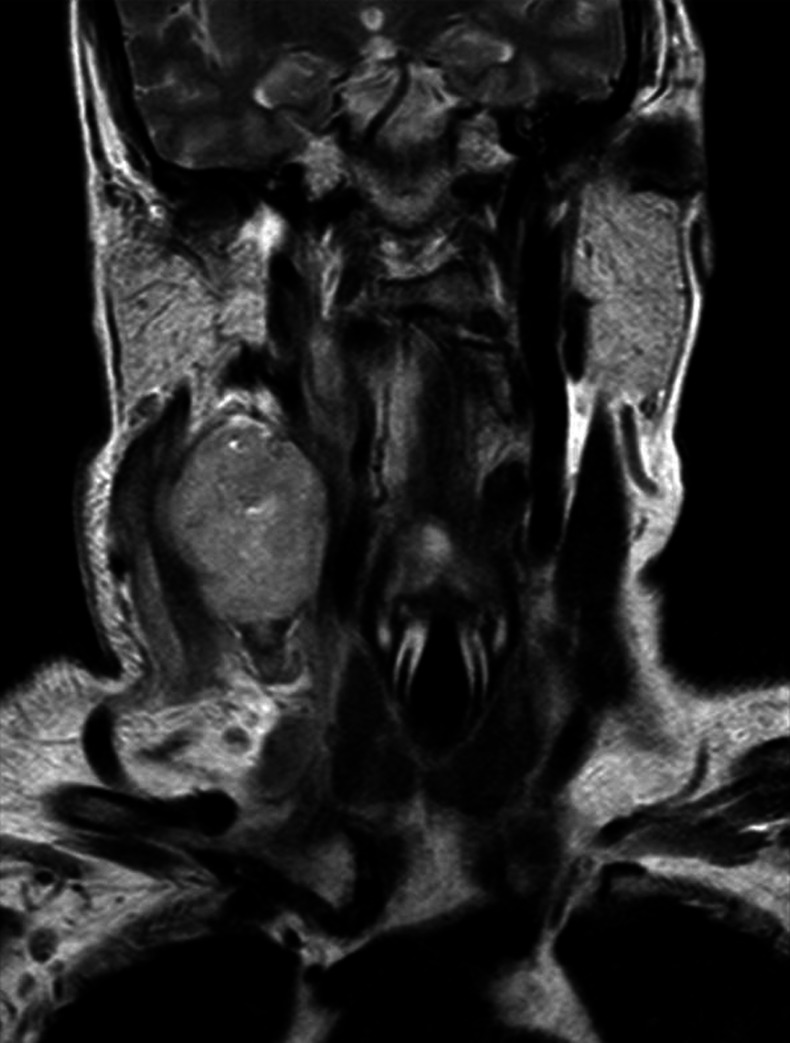

Further MRI of the neck was also requested due to the high suspicion of a malignant mass as well as a PET scan to identify any primary. MRI neck showed an ill-defined low T1/high T2 mass in level 2/3 of the neck on the right (figure 2). The mass measured 4.3×4.1 cm in axial dimension and 5.2 cm in maximal craniocaudal dimension. On diffusion-weighted imaging the mass was hypercellular. There was marked surrounding oedema/high signal, especially the right sternocleidomastoid muscle, which is directly involved in the process. Superiorly the mass extended towards the skull base, medialising the carotid. There was an abnormal signal in the right retropharyngeal and parapharyngeal space, with significant abnormal signal also noted in the right anterior arch of the atlas and also on the lateral mass of C2. No mass seen in the oral cavity, larynx or hypopharynx. There were no contralateral enlarged cervical lymph nodes.

Figure 2.

MRI neck showed an ill-defined low T1/high T2 mass in level 2/3 of the neck on the right, medialising the right carotid artery.

The PET scan confirmed the presence of a large nodal mass in the right level II, necrotic with the walls showing intense fluorodeoxyglucose uptake, measuring 7 cm × 4.7 cm × 5.3 cm. However, the PET scan did not identify any abnormal uptake in the chest/abdomen/pelvis or skeleton.

Differential diagnosis

The most plausible diagnosis was that the neck abscess was a malignant mass. This suspicion was derived from the fact that the mass was hard, cold and non-fluctuant with no systemic features of infection. The suspicion was reinforced by the results of the scans, which showed a mass of an aggressive nature.

Atypical organisms were also suspected to be a plausible cause of the abscess because the patient was otherwise asymptomatic. As such, during histological analysis, the sample taken was also tested for acid-fast bacilli to exclude tuberculosis, as this could have been a ‘cold abscess’. But the test for tuberculosis was negative.

Treatment

In the meantime the patient represented again 3 weeks after her original presentation with oozing and pain due to mass pressure symptoms. The patient then underwent incision and drainage of the mass to relieve the pressure symptoms experienced and also to take tissue for histological analysis and diagnosis.

Histological analysis of the tissue revealed acutely inflamed granulation tissue with foamy macrophages. There was no evidence of malignancy or lymphoid tissue. Most importantly, the culture grew L lactis cremoris bacteria sensitive to augmentin. Indeed, after direct questioning the patient reported drinking unpasteurised milk and ingesting cheese acquired from a farmer's market 3–4 months prior to her presentation and that is possibly the reason behind the positive lactococcus bacteria culture. As such, L lactis cremoris infection was diagnosed and the patient was treated with antibiotics and weekly dressings.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient recovered rapidly and no acid-fast bacilli grew after 42 days incubation. Repeat ultrasound scan neck in 4 weeks revealed complete resolution of the neck abscess. Long-term good diabetic control is to be instituted by the patient's general practitioner to strengthen the patients’ immune system and reduce the risk of infections.

Discussion

There are five species in the genus Lactococcus; of which L lactis ssp. lactis, L lactic ssp. cremoris and L lactis ssp. lactis biovar diacetylactis are used for the production of fermented dairy products and production of cheddar cheese.6 Therefore, exposure to unpasteurised dairy products has been suggested as a risk factor of L lactis cremoris infection. While many bacteria commonly used in food preparation are killed during digestion, it is known that lactococcus remains viable after transit through the gastrointestinal tract.7 This is thought to be the mechanism of L lactis cremoris infection in humans.

L lactis cremoris is commonly regarded as non-pathogenic in immunocompetent adults; however, we report the 15th case to our knowledge of this pathogen causing clinically significant infection. Previously, four cases of bacterial endocarditis, one of septicemia, two liver abscesses and one each of necrotising pneumonitis, purulent pneumonitis, septic arthritis, deep neck infection, two brain abscesses peritonitis, ascending cholangitis and canaliculitis (3–5) have been reported. Of these, it appears that nine were immunocompetent patients. All of the case reports were in adults except one.

To date, however, there have been no reports of neck abscess in the UK. Moreover, this is the first report of an infection, in which a neck abscess originated in the neck with no evidence of mucosal breach, caused by L lactis cremoris. Of the previously reported cases, six have been associated with a clear history of exposure to unpasteurised dairy products; in one of these cases, the organism was isolated from the milk product. Our patient reports drinking unpasteurised milk and ingesting cheese acquired from a farmer's market 3–4 months prior to her presentation.

There is no standard for treatment of L lactis cremoris infection. In the previously reported cases, antibiotic regimens based on the result of susceptibility test were the mainstay of treatment, and penicillin or third-generation cephalosporin was chosen most commonly.8–10 In this case, we chose coamoxiclav based on the result of susceptibility testing.

Learning points.

This report reinforces the existing evidence that Lactococcus lactis cremoris is a potential pathogen in humans in many different systems, both in immunocompetent and in immunocompromised adults.

Atypical organisms should always be considered in the working diagnosis of an atypical neck mass especially due to the rise in popularity of organic farming and the promotion of unpasteurised products.

Footnotes

Contributors: SH, PL and PK were all involved in patient care. SH and PL carried out the review of literature and were jointly responsible for drafting and revising the manuscript. PK has provided editorial and clinical supervision.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Schleifer KH, Kraus J, Dvorak C, et al. Transfer of Streptococcus lactis and related streptococci to the genus Lactococcus gen. nov. Syst Appl Microbiol 1985;2013:183–95 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unsworth PF. The isolation of streptococci from human faeces. J Hyg (Lond) 1980;2013:153–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mat O, Rossi C, Beauwens R, et al. Peritonitis due to Lactococcus cremoris in an automated peritoneal dialysis patient. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003;2013:2690–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mofredj A, Beldjoudi S, Farouj N. Purulent pleurisy due to Lactococcus lactis cremoris. Rev Mal Respir 2006;2013:485–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies J, Burkitt MD, Watson A. Ascending cholangitis presenting with Lactococcus lactis cremoris bacteraemia: a case report. J Med Case Reports 2009;2013:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basaran P, Basaran N, Cakir I. Molecular differentiation of Lactococcus lactis subspecies lactis and cremoris strains by ribotyping and site specific-PCR. Curr Microbiol 2001;2013:45–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drouault S, Corthier G, Ehrlich SD, et al. Survival, physiology, and lysis of Lactococcus lactis in the digestive tract. Appl Environ Microbiol 1999;2013: 4881–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell P, Dealler S, Lawton JO. Septic arthritis and unpasteurised milk. J Clin Pathol 1993;2013:1057–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akhaddar A, El Mostarchid B, Gazzaz M, et al. Cerebellar abscess due to Lactococcus lactis. A new pathogen. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002;2013:305–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koyuncu M, Acuner IC, Uyar M. Deep neck infection due to Lactococcus lactis cremoris: a case report. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2005;2013:719–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]