Abstract

We present a case of a salivary gland tumour in a 25-year-old woman with lymphadenopathy and a clinical suspicion of lymphoma. The patient had a history of rapidly enlarging mass near angle of jaw which was resected and sent for histopathological examination. A final diagnosis of acinic cell tumour with dedifferentiation was made by histomorphological and immunohistochemical studies. Acinic cell tumour can mimic any salivary neoplasm phenotypically because of its varied architectural patterns of presentation with varied cell types, hence called the harlequin of salivary gland. Acinic cell tumour with dedifferentiation is a rare aggressive variant and requires adjuvant radiotherapy for better prognosis, hence the need for accurate diagnosis and communication to the surgeon

Background

Acinic cell carcinoma is a rare parotid malignancy and constitutes approximately 3% of all parotid tumours with 80% occurring in parotid glands.1 Because of varied architectural patterns of presentation with varied cell types, it can mimic any salivary neoplasm-lymphoma, malignant pleomorphic adenoma, basal cell carcinoma, etc, clinically and histologically. Dedifferentiated acinic cell carcinomas are rare aggressive variants requiring adjuvant radiotherapy which improves survival.2

We hereby present a case of dedifferentiated acinic cell tumour in minor salivary gland posing a diagnostic dilemma with its heterogeneous presentation and ever confusing histopathological and staining characteristics.

Case presentation

A 25-year-old female patient presented to the department of surgery with a rapidly enlarging mass near angle of left jaw measuring 4×4 cm was tender, firm and non-mobile and fixed to underlying mandible that was initially painless and slow growing for 6 months. The patient developed another mass below the chin after 4 months measuring 2×2 cm was firm, non-tender and mobile. The patient had unilateral painless cervical lymphadenopathy. In the light of clinical examination a provisional diagnosis of lymphoma was made.

Grossly the tumour mass measured 6×3.5×3.5 cm, partially capsulated with whitish areas, firm with multiple, white nodules along with areas of haemorrhage and congestion. The mass suspected to be lymph node measured 3.5×3 cm, creamish-white in colour with firm whitish areas with focal haemorrhage were seen (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Gross image showing resected, partially capsulated mass with whitish firm areas with multiple, white nodules along with areas of haemorrhage and congestion.

Investigations

On microscopy sections from both masses showed large infiltrating sheets of pleomorphic cells in varied structural patterns. The tumour had few areas with lobular architecture admixed with lymphoid tissue (figure 2). These cells however had clearing of cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei and prominent eosinophilic nucleoli (figure 3). The tumour also showed areas of poorly differentiated eosinophillic cells with mitotic figures and a prominent lymphoid tissue with germinal centres admixed with tumour cells (figures 4 and 5) which helped us in clinching diagnosis. Immunohistochemically tumour cells were leucocyte common antigen (LCA) negative (figure 6) which excluded diagnosis of primary lymphoma. Tumour cells were cytokeratin positive (figure 7). Lymphoid cells were LCA and CD 20 positive (figure 8). Hence a final diagnosis of dedifferentiated acinic cell carcinoma with poorly differentiated areas was made in the light of histopathological findings, especially the presence of lymphoid cells and germinal centres among the tumour cells, which were correlated imunohistochemically.

Figure 2.

Large infiltrating sheets of pleomorphic tumour cells in sheets admixed with lymphoid tissue.

Figure 3.

Tumour cells showing clearing of cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei and prominent eosinophilic nucleoli admixed with lymphoid tissue.

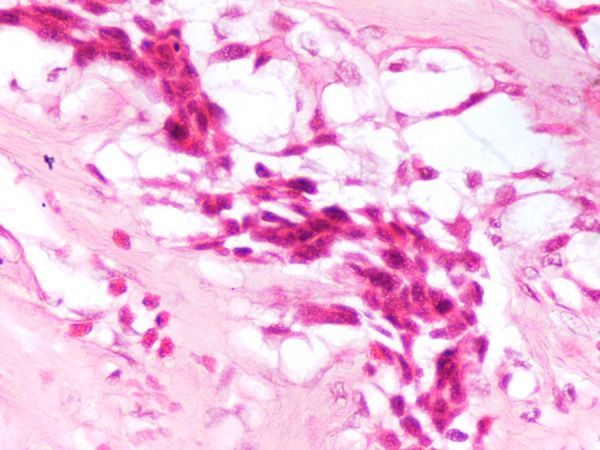

Figure 4.

Poorly differentiated eosinophillic cells admixed with tumour cells and lymphocytes.

Figure 5.

Poorly differentiated eosinophillic cells with mitotic figures admixed with tumour cells.

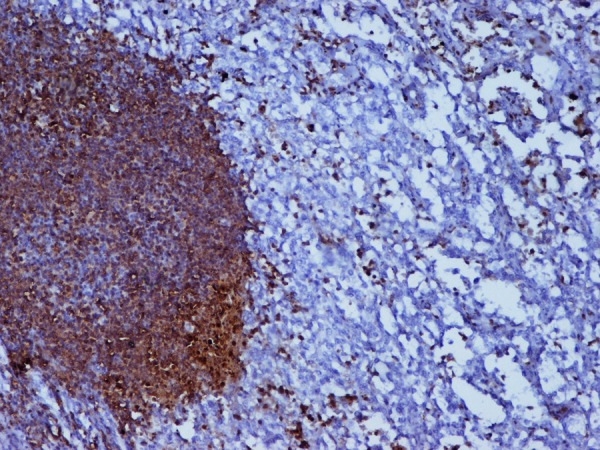

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemically tumour cells showing leucocyte common antigen (LCA) negativity along with LCA positive lymphoid tissue.

Figure 7.

Tumour cells showing cytokeratin positivity.

Figure 8.

Lymphoid cells showing leucocyte common antigen positivity.

Differential diagnosis

The primary differential which needed to be excluded clinically in our case was primary salivary gland lymphoma. Also in microscopy the predominant lymphoid infiltrate into the substance could also be mistaken for lymphoma. Immunohistochemically the accurate diagnosis was achieved as the cells were cytokeratin positive; it suggested epithelial nature of the lesion. Moreover, the cells were negative for LCA excluding primary lymphoma from diagnosis.

Sometimes oncocytomas may be confused with acinic cell carcinoma because of similar cell arrangement and cytoplasmic granularity; however, the nuclei of acinic cell carcinomas are peripherally located in contrast with the central round nuclei of oncocytomas.

Many a times acinic cell carcinoma mimics adenoid cystic carcinoma; however, the absence of basement membrane like material often confirms diagnosis apart from characteristic adenoid cystic pattern elsewhere in a adenoid cystic carcinoma.

Other differentials which may be considered in microcystic pattern of the tumour include polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma but the microcystic pattern is usually focal with scant lymphoid tissue in polymorphous low grade adenocarcinoma.

Some cases of myoepithelioma may also mimic acini cell tumour.

Treatment

The patient had initially undergone surgery and after the histopathological diagnosis was referred to radiotherapy because this variant responds better to adjuvant radiotherapy.2 Details of the number of radiotherapy cycles the patient underwent could not be known.

Outcome and follow-up

The diagnosis of dedifferentiated acinic cell carcinoma itself indicates poorer prognosis;3 however, there were abundant lymphoid cells and microcystic pattern which indicated a favourable clinical course. The patient after being referred to radiotherapy was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Acinic cell carcinomas represent approximately 2% of salivary gland tumours, with almost 90% arising in the parotid gland. The rest involve the submandibular and the minor salivary glands4 This tumour is more common in women, and the peak incidence is in the fifth and sixth decades of life. The tumour may arise in ectopic salivary gland tissue, or it may be multiple or bilateral. On gross examination, the lesional tissue is often well delineated, brown and round. It may resemble a pleomorphic adenoma, but it is less moist and myxoid in appearance. Recurrent tumours are indistinguishable from pleomorphic adenomas grossly.5

Microscopically, the tumour cells resemble the serous cellular elements of the normal parotid gland with a finely granular cytoplasm. The cytoplasmic secretory granules are periodic acid Schiff positive, and amylase activity is demonstrable in the cytoplasm. In addition to the classic serous cells, the lesional tissue may be composed of clear cells and ductal cells. Some other studies have identified solid acinar, microcystic, papillary cystic and follicular microscopic subtypes6; however, subclassification is usually not fruitful because several cell types and architectural patterns may be present in the same tumour.

In general, histological appearance however does not predict the clinical behaviour of tumour. If the tumour is well encapsulated and it shows no intratumoral vascular permeation, it is less likely to recur than it is in those instances in which the encapsulation is incomplete and vascular invasion is present.4 Local recurrence can be expected in approximately 20% of cases. Regional lymph node metastases and distant metastases are present in 10% and 6% of patients, respectively.4 Some studies have found a prognostic correlation with histological classification of well differentiated to poorly differentiated acinic cell carcinomas.3 The concept of dedifferentiated acinic cell carcinoma refers to a composite tumour with conventional acinic cell carcinoma and poorly differentiated or undifferentiated carcinoma.7 8 This is a highly aggressive tumour that requires adjuvant treatment.2 The papillocystic variant has an unusually bad clinical outcome, so identifying this subtype is important.4 Overall, the 5-year survival for acinic cell carcinoma is 83%.9

There are few reports of fine needle aspiration cytological diagnosis of acinic cell tumour in which the lesions mostly shows cells with poorly and well differentiated morphology distributed in small and larger, branching groups with acinic morphology. The aspiration cytology suggested a poorly differentiated component along with acinic cell neoplasm and final diagnosis was achieved only after histopathological examination.10 11

Also a report describes intense fluorodeoxyglucose uptake was noted in the parotid gland mass by F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography/CT for initial staging work-up.12

Hence correct diagnosis of this variant is quintessential for better treatment and correct management in light of its poor prognosis as the patient in our case was then referred to radiotherapy for better survival.

Learning points.

Acinic cell tumour can have varied architectural types and cell morphology and can be confused with multiple neoplasms clinically and histologically.

Acinic cell tumour with dedifferentiation is rare aggressive variant requiring adjuvant radiotherapy.

It is imperative to diagnose correctly the dedifferentiated variant and to communicate it for better prognosis

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Guha S, Guha R, Manikantan K, et al. Synchronous bilateral acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid. J Cancer Sci Ther 2012;2013:92–3 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuffin JR, Daniel F, Davies AS, et al. Acinic cell carcinoma—Plymouth's experience with postoperative radical radiotherapy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1989;2013:186–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batsakis JG, Chinn EK, Weimert TA, et al. Acinic cell carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of thirty-five cases. J Laryngol Otol 1979;2013:325–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munteanu MC, Mărgăritescu C, Cionca L, et al. Acinic cell carcinoma of the salivary glands: a retrospective clinicopathologic study of 12 cases. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2012;2013:313–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stacey E Mills. Sternbergs diagnostic and surgical pathology. Vol. 1. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins 2010:839–41 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellis GL, Corio RL. Acinic cell adenocarcinoma. A clinicopathologic analysis of 294 cases. Cancer 1983;2013:542–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanley RJ, Weiland LH, Olsen KD, et al. Dedifferentiated acinic cell (acinous) carcinoma of the parotid gland. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1988;2013:155–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henley JD, Geary WA, Jackson CL, et al. Dedifferentiated acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland: a distinct rarely described entity. Hum Pathol 1997;2013:869–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffman HT, Karnell LH, Robinson RA, et al. National cancer data base report on cancer of the head and neck: acinic cell carcinoma. Head Neck 1999;2013:297–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnykutty S, Miller CH, Hoda RS, et al. Fine-needle aspiration of dedifferentiated acinic cell carcinoma: report of a case with cyto-histological correlation. Diagn Cytopathol 2009;2013:763–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.González-Peramato P, Jiménez-Heffernan JA, López-Ferrer P, et al. Fine needle aspiration cytology of dedifferentiated acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland: a case report. Acta Cytol 2006;2013:105–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyun O, Joo Y, Ryung Jung L, et al. F-18 FDG PET/CT findings of dedifferentiated acinic cell carcinoma. Clinl Nucl Med 2010;2013:473–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]