Abstract

We present a middle-aged man with history of lung adenocarcinoma, who was admitted with massive haemoptysis secondary to severe thrombocytopenia. Two weeks prior he was started on enoxaparin for a newly diagnosed pulmonary embolus and at that time required blood transfusions for anaemia. Our initial diagnosis was heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. His platelet count, however, did not improve despite receiving argatroban and platelet transfusions. Hence, we suspected post-transfusion purpura (PTP) and started him on intravenous immunoglobulin which brought his platelet count to normal levels. The serotonin-release assay was negative and platelet-antibody test was positive confirming PTP as our diagnosis. The patient eventually was transferred to hospice care because of the advanced stage lung cancer and died of respiratory failure.

Background

Post-transfusion purpura (PTP) is a rare and potentially fatal transfusion reaction leading to severe thrombocytopenia occurring approximately 1 week after blood transfusions. Its incidence is approximately 1 in 50 000–100 000 blood transfusions and occurs more commonly in multiparous women. This disorder is mediated by alloantibodies against specific platelet antigens, most commonly PlA1 (HPA-1a). Other antigens such as Zwb, Bak, Lek, Ko and Pen have also been associated with this disease. Schulman et al in 1961 were the first to describe the phenomenon of post-transfusion thrombocytopenia. Since then there have been less than 15 documented cases of PTP occurring in men making our case unique. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) has been used as the first-line therapy; however, corticosteroids and plasmapheresis have proven successful. Our case is one of the rare instances of this phenomenon occurring in men and highlights the importance of keeping a high suspicion of PTP when most of the common causes of thrombocytopenia have been ruled out. This is because PTP can cause life-threatening bleeding which can be prevented by early suspicion and effective treatment and hence it is important to raise awareness of this transfusion complication.

Case presentation

We present a 52-year-old man who has a history of Stage IV adenocarcinoma of the left lung, which was diagnosed in September 2011, for which he has received 6 cycles of cisplatin and docetaxel and completed palliative radiation on June 2012. He also has a history of polysubstance abuse and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on 6 l oxygen. He was diagnosed 2 weeks prior to admission with a right-sided pulmonary embolism and is currently taking enoxaparin. He presented to our hospital with worsening haemoptysis for over 4 days and extreme fatigue. He also had worsening cough and bilateral chest pain. He denied any fevers, worsening dyspnoea, palpitations, haematuria, melena, haematochezia, haematemesis or epistaxis. He has never had any surgeries. He was a 20 pack-year smoker and quit in September 2011. He has a history of polysubstance abuse and is on methadone treatment. He is currently incarcerated for the past 5 years. Both of his parents have had ischaemic cardiomyopathy and diabetes. However, there is no family history of malignancies in his family or haematological disorders.

On examination he was afebrile, tachycardic, normotensive and his oxygen saturation was 91% on 6 l oxygen. He had diminished breath sounds throughout his entire left lung and rhonchi were heard on the right side of his chest. His cardiovascular, abdominal and neurological exam was benign. He had few purpuric spots seen on his left upper extremities and bilateral lower extremities. His left upper extremity appeared swollen as well.

Investigations

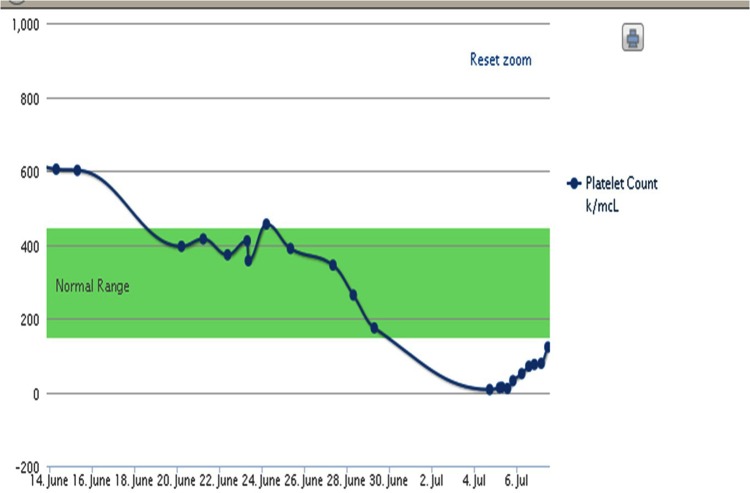

His initial labwork revealed normal electrolytes. His haemoglobin was 8.8 g/dl(baseline 8.4 g/dl), white blood cell count of 15 120/mcl (baseline 13 000/mcl) and platelet count of 7000/mcl (was 174 000/mcl 2 weeks ago; figure 1). Due to concern of HIT we rechecked CT angiogram and venous Dopplers of all extremities. His CT chest revealed right-sided segmental and subsegmental emboli, which were unchanged from his CTA 2 weeks ago. It also revealed worsening tumour progression on his left side with complete lung collapse. Venous Dopplers revealed stable left cephalic and basilica vein thrombus. A heparin PF4 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and serotonin release assay were sent as well. The ELISA eventually came back as 0.638, however, the serotonin release assay was negative and platelet antibody was positive.

Figure 1.

Platelet counts over a period of approximately 21 days from presentation.

Differential diagnosis

The differentials that were considered initially for this patient were HIT, disseminated intravascular coagulation, bone marrow suppression from past chemotherapy and radiation. We also believed that his haemoptysis may also be related to cancer progression or alveolar haemorrhage on top of his thrombocytopenia. PTP was thought of when his platelet counts were not improving and when it was brought to our notice that he had a blood transfusion about a week prior to onset of symptoms.

Treatment

Our initial management was focused on reversing his thrombocytopenia and treatment for HIT. He was transfused 6 units of platelets and was started on Argatroban. We reviewed the medications he received during his last admission. He was initiated on a heparin infusion for 5 days and then switched to enoxaparin. He was not initiated on any other medications which could contribute to his thrombocytopenia. He did receive 2 units of blood during his last admission because his haemoglobin did drop below 7 g/dl. Despite platelet transfusion there was no improvement in his platelet count. His haemoptysis worsened as well. We decided to discontinue the Argatroban and transfuse him another 6 units of platelets. Despite a total of 12 units of platelets his platelet count still remained below 50 000/hpf. The PF4 ELISA value was 0.638 which was moderately positive; however, it did not establish the diagnosis of HIT. Since he did receive blood during his last admission there was a concern for PTP and hence checked his platelet antibody studies. We initiated IVIg 500 mg/kg for a total of 4 days. After completion of IVIg his platelet count rose to 292 000/mcl.

A bronchoscopy was performed and a site of bleeding was seen on the left lower lobe and thrombin was applied. Since his hemoptysis had resolved and his platelet count had improved, we faced a dilemma whether to restart his anticoagulation using unfractionated heparin of argatroban as his serotonin-release assay (SRA) result was still pending. After discussing with the haematology specialists Argatroban was restarted and he was eventually transitioned to Warfarin. The patients’ platelet count never dropped after IVIg and he did not have any episodes of hemoptysis after IVIg was given. A week after presenting to the hospital platelet antibody studies came back positive mainly to HLA-1 and his SRA was negative.

Outcome and follow-up

His platelet count eventually recovered and he had no further episodes of hemoptysis or bleeding manifestations. However, over the next few weeks his respiratory status worsened and he was developing worsening pleural effusions and atelectasis of his lung. After discussion with the family it was decided to place the patient to hospice care and he eventually died a few days later from respiratory failure.

Discussion

PTP is one of the uncommon causes of thrombocytopenia. It occurs approximately 7–10 days after a blood transfusion.1 2 Schulman et al3 were the first to identify that thrombocytopenia can occur as a result of complement fixation of platelets if they carry a specific antigen. They studied the causes of neonatal thrombocytopenia and concluded that maternal blood gets immunised against fetal platelet antigens and causes a complement-induced destruction of fetal platelets.3 The antigen responsible for most of the cases is PlA1.4 The patients’ platelets are initially PlA1 antigen negative and get immunised when exposed to blood containing PlA1. This makes them prone to thrombocytopenia when exposed to blood with PlA1-positive platelets again. As a result PTP is more commonly seen in multiparous women who have been exposed to fetal PlA1-positive platelet.5

PlA1 is not the only antigen associated with PTP. Other antigens include PIA (Zw), ple, Bak (Lek), Ko and Pen (Yuk). The PlA1 antigen has been localised to an epitope on GPIIIa, p1Ei on GPlba, Baka on llb and Pen on GPIIIa.6 There are still various theories regarding the pathophysiology of PTP. Another theory suggested by Stricker et al7 mentions that PlA1 antigen-positive and PlA1 antigen-negative platelets share certain antigens and there could be an alloantibody response mounted against these common antigens leading to platelet destruction. Gockerman and Schulman described in their study that although antibodies against PlA1 bound to all the platelets, complement fixation did not occur on all the antigen-antibody complexes.4 They believe more than one antibody response is mounted, one of which may prevent complement fixation. Just like in drug-induced thrombocytopenia, the initial antigen-antibody reaction can be fulminant and life-threatening. However, unlike drug-induced thrombocytopenia, PTP may persist for approximately a month after the insult occurs. As this antigen is present in only 1.5% of the population the incidence of PTP is 1 in 5000–10 000units of blood transfused.8

Thrombocytopenia which occurs secondary to PTP is self-limited, however, it can be life-threatening if not detected early. This is because as mentioned in our case severe bleeding can occur and hence prompt treatment is required. Even without the results of diagnostic labwork, treatment can be initiated. PTP can easily be misdiagnosed as HIT.9 Using the HIT expert panel probability (HEP) score10 many cases that resemble HIT can be ruled out. It is important to assess if a patient has received any blood transfusions in the past few weeks as both these conditions can overlap. Other aetiologies of thrombocytopenia such as infections, medications, bone marrow disorders, splenomegaly and consumptive pathologies too need to be ruled out.

Treatment of PTP includes IVIg, corticosteroids or plasmapheresis.11–13 High dose IgG treatment too has been proven beneficial. A dose of either 1 g/kg for 2 days or 500 mg/kg for 5 days has been a standard treatment protocol. It takes approximately 4–5 days for the platelet count to rebound above100 000. Eckart et al14 believe high dose IgG should be the standard of treatment for PTP but further studies need to be performed too decide if one treatment protocol is more beneficial than another. Corticosteroids too have been proven beneficial and can be tried if IVIg12 fails to improve platelet counts. Plasmapheresis can be performed if no other treatment works as the patient's antibodies can be removed via this method.13

Learning points.

Post-transfusion purpura (PTP) usually occurs approximately 1 week after blood transfusion and is seen in multiparous women leading to life-threatening bleeding because of low platelet counts.

The most common antigen responsible for PTP is PlA1.

High dose intravenous immunoglobulin appears to be the best treatment and should be initiated when the suspicion arises of PTP.

This condition can be easily confused with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

Footnotes

Contributors: PP is the primary author in this case report. GSP assisted with the writing of the case and researching literature regarding the topic. JS and RK were the haematology experts reviewed and gave expert opinions on the case. RK also added points in the management of post-transfusion purpura.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Zeigler Z, Murphy S, Gardner FH. Post-transfusion purpura: a heterogenous condition. Blood 1975;2013:529–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lau P, Sholtis CM, Aster RH. Post-transfusion purpura: an enigma of alloimmunization. Am J Hematol 1980;2013:331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shulman NR, Aster RK, Leitner A, et al. Immunoreactions involving platelets. V post-transfusion purpura due to a complement-fixing antibody against a genetically controlled platelet antigen. A proposed mechanism for thrombocytopenia and its relevance in ‘autoimmunity’. Clin Invest 1961;2013:1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gockerman JP, Schulman NR, et al. Isoantibody specificity in post-transfusion purpura. Blood 1973;2013:817–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waters AH. Post-transfusion purpura. Blood Rev 1989;2013:83–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kickler TS, Herman JH, Furihata K, et al. Identification of Bakb, a new platelet-specific antigen associated with post-transfusion purpura. Blood 1988;2013:894–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stricker RB, Lewis BH, Corash L, et al. Post-transfusion purpura associated with an autoantibody directed against a previously undefined platelet antigen. Blood 1987;2013:1458–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shtalrid M, Shvidel L, Vorst E, et al. Post-transfusion purpura: a challenging diagnosis. Isr Med Assoc J 2006;2013:672–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lubenow N, Eichler P, Albrecht D, et al. Very low platelet counts in post-transfusion purpura falsely diagnosed as heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: report of four cases and review of literature. Thromb Res 2000;2013:115–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuker A, Arepally G, Crowther MA, et al. The HIT Expert Panel (HEP) Score: a novel pre-test probability model for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia based on broad expert opinion. J Thromb Haemost 2010;2013:2642–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becker T, Panzer S, Maas D, et al. High-dose IgG for post-transfusion purpura-revisited. Blut 1988;2013:163–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puig N, Sayas MJ, Montoro JA, et al. Post-transfusion purpura as the main manifestation of a trilineal transfusion reaction, responsive to steroids: flow-cytometric investigation of granulocyte and platelet antibodies. Ann Hematol 1991;2013:232–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laursen B, Morling N, Rosenkvist J, et al. Post-transfusion purpura treated with plasma exchange by haemonetics cell separator. Acta Medica Scandinavica 1978;2013:539–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker T, Panzer S, Maas D, et al. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin for post-transfusion purpura. Br J Hematol 1985;2013:149–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]