Abstract

We report the case of a 53-year-old lady who presented with a lump in her left breast. Her initial investigations demonstrated a grade III invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast that was tethered to the pectoralis major; imaging and cytology also revealed metastatic nodes in the left axilla. After undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy with evidence of clinical and radiological tumour response, a wire-guided wide local excision and axillary node clearance was performed. When a histological analysis of the specimen was performed, there was no evidence of a viable metastatic tumour in the axillary lymph nodes, but there were several areas of extramedullary haematopoiesis. There are only two other reports in the literature of this finding. This could represent a potential source of false-positive diagnosis of axillary metastasis from breast cancer. It would be prudent to consider biopsy prior to clearance if there are megakaryocytes in axillary node cytology.

Background

The diagnosis and management of breast cancer are based upon the ‘triple assessment’ of breast disease consisting of clinical, radiological and pathological assessment. Pathological axillary lymph nodes on ultrasound imaging usually undergo fine needle aspiration cytology in order to confirm the metastatic spread of disease. This case highlights the importance of considering extramedullary haematopoiesis as a possible differential diagnosis when evaluating cytological specimens that contain atypical cells such as multinucleate cells.1 2 3 It may also be important to consider whether chemotherapeutic agents and other medications used, such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), could have a role in explaining this unusual histological finding.4 When such findings are demonstrated on cytology, it may be reasonable to consider sentinel node biopsy to confirm metastatic disease prior to proceeding with axillary node clearance.

Case presentation

A 53-year-old lady presented with a self-detected lump in her left breast with no other associated symptoms of breast disease. Clinical examination revealed a large mass in the upper outer quadrant of the left breast that appeared to be tethered to the pectoralis major; there was no evidence of palpable axillary lymphadenopathy. Ultrasound assessment demonstrated a 37×22×46 mm hypoechoic mass highly suspicious for malignancy with pathological nodes in the corresponding axilla. On mammography, there was a dense lobulated mass with ill-defined anterior margins in the upper outer quadrant measuring at least 4.5 cm and CT demonstrated an enlarged (2.7 cm) left axillary lymph node with adjacent soft tissue stranding consistent with regional involvement.

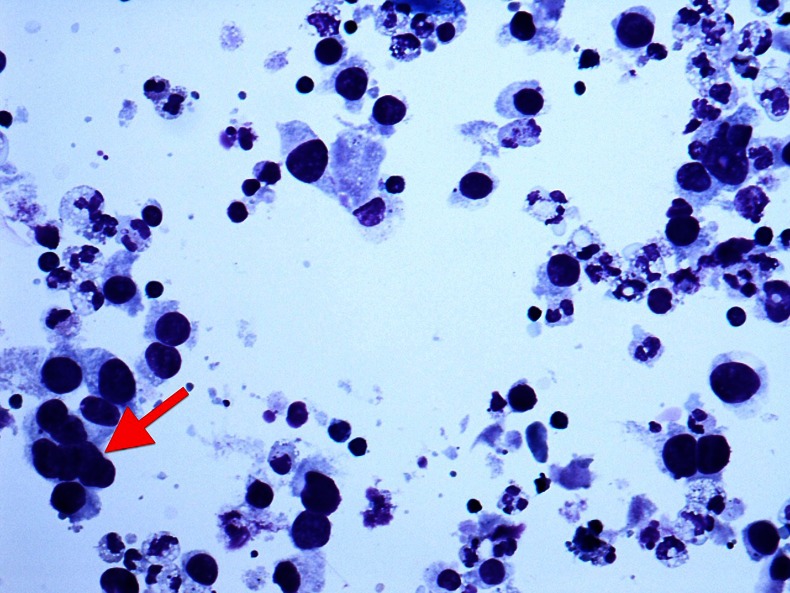

A core biopsy of the breast lesion was performed showing grade III invasive ductal carcinoma with focal ductal carcinoma in situ but with no evidence of lymphovascular invasion or perineural invasion. The lesion was determined to be oestrogen receptor—negative, progesterone receptor—negative and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2)—negative. Initial fine needle aspiration of the left axillary lymph nodes showed numerous pleomorphic, large atypical glandular epithelial cells representing metastatic breast carcinoma along with multinucleate cells, which are atypical findings in metastatic disease of the axilla (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preoperative fine needle aspiration cytology of an axillary node demonstrating malignant cells and a multinucleate cell (arrow).

The case was discussed at our multidisciplinary team meeting after completion of staging with CT scanning and an isotope-labelled bone scan which did not show evidence of distant metastases or organomegaly. It was decided that she would be a candidate for neoadjuvant chemotherapy with the intent of being able to offer breast-conserving surgery. She was initially treated with four cycles of epirubicin and cyclophosphamide, but after completing the fourth cycle of chemotherapy repeat imaging, she did not show any significant tumour response. For her next two cycles of chemotherapy, she received docetaxel along with G-CSF from days 3 to 8 of each cycle to minimise myelosuppression. Following her sixth cycle of chemotherapy, the lesion measured 20×10 mm on ultrasound and was no longer clinically palpable, demonstrating good tumour response to neoadjuvant therapy. The treatment regimen of anthracyclines followed by taxanes is commonly used practice in the neoadjuvant setting as there is significant evidence to support this from randomised controlled trials.5

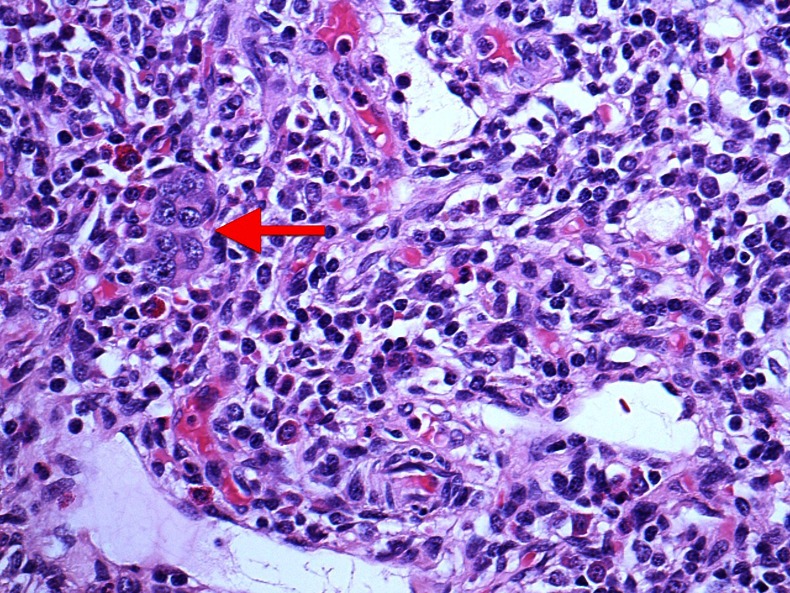

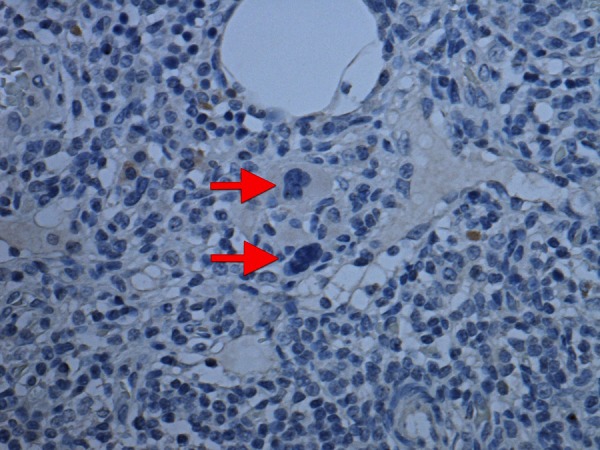

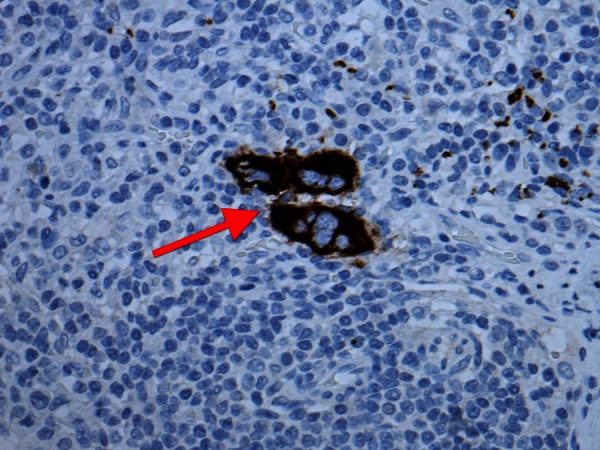

The patient then underwent a wide local excision and axillary node clearance and histological analysis of the resection specimen was performed. On microscopy of the breast specimen, there were islands of residual grade III invasive ductal carcinoma surrounded by lymphocytic infiltrate and dense fibrous stroma, indicating a chemotherapeutic effect. Among the residual tumours identified were a few multinucleate cells which were unusual in appearance. The viable remaining tumour was 12×8 mm and the closest margin was 3 mm. In the axillary specimen, no nodes could be identified that contained a viable metastatic tumour; unusually, megakaryocytes with positivity for myeloperoxidase and glycophorin A were demonstrated in a number of nodes, confirming the presence of extramedullary haematopoiesis (see figures 2–4). There was also evidence of fibrous scarring in 2 of the 17 nodes identified, which could represent previous involvement by tumours but is not conclusive.

Figure 2.

Large multinucleate cells (arrow) within a lymph node accompanied by a sparse haematopoietic background seen in a postoperative specimen of axillary clearance.

Figure 3.

Multinucleate cells (arrow) negative for an epithelial marker (AE1/AE3) as seen in lymph nodes of axillary clearance.

Figure 4.

Multinucleate cells (arrow) positive for a megakaryocytic marker (CD42b) as seen in lymph nodes of axillary clearance.

The patient had no history of haematological disorder and we found no evidence of concurrent haematopoietic disorder to account for extramedullary haematopoiesis. Prior to chemotherapy, her haemoglobin level was 13.1 g/dl with a mean corpuscular volume of 89.6 fl and a total white cell count of 9×109/l. After completing neoadjuvant chemotherapy, there was a drop in haemoglobin levels to 10.6 g/dl, which at 6 months post chemotherapy returned to pretreatment levels at 13.2 g/dl. Serum levels of vitamin B12, folate, ferritin and lactate dehydrogenase were performed after chemotherapy and were all in the normal range, as was that of serum electrophoresis. As there was no evidence of abnormal haematopoiesis from these findings, no further investigation into haematological status was deemed necessary.

Outcome and follow-up

Following breast-conserving surgery with complete clearance of residual disease, the patient underwent a good recovery and is currently undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy of her chest wall and supraclavicular fossa after discussion with the oncologists. There have been no further changes in the haematology results or clinical examination to suggest a pathological cause for the axillary node findings.

Discussion

Extramedullary haematopoiesis is defined as the occurrence of one or more of the trilineages of haematopoietic cells outside of the bone marrow and its occurrence in axillary nodes is very rare. There have only been two previous reports in the literature of extramedullary haematopoiesis in axillary lymph nodes after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced breast cancer.1 2 In one of these cases, metastatic carcinoma of the axillary nodes was identified from intraoperative specimens but found on later evaluation to demonstrate megakaryocytes with no evidence of viable metastatic cells.2 In the other case, one micrometastatic deposit was identified in the axillary clearance but all nodes contained several megakaryocytes.1 There have been previous reports of uncommon benign abnormalities of lymph nodes such as nevus cell aggregates, benign (heterotrophic) glands and multinucleated macrophages being mistaken for metastatic carcinoma.6 7 The multilobulated and hyperchromatic nuclei of megakaryocytes can make differentiation from metastatic cells on paucicellular aspirates very difficult, accounting for this misinterpretation.

There is no evidence in the literature that any of the chemotherapeutic agents could be implicated in the aetiology of extramedullary haematopoiesis, but there is evidence that it may be drug induced by G-CSF.8 Both in this case and in one of the previous case reports, the patient received G-CSF in the neoadjuvant period, so there is a theoretical possibility that this could account for this unusual histological finding.

This case highlights a rare and unusual postoperative histology finding that was not congruent with the preoperative assumptions made from histology and cytology. It is important that the clinical, radiological and histological findings are considered carefully when assessing breast disease and the rare but important differential of megakaryocytes should be added to a list of differential diagnoses when assessing fine needle aspirates of axillary lymph nodes in breast disease. In this case, there was evidence of malignant cells in the cytology aspirate along with abnormal multinucleate cells. In future, when dealing with cases similar to this, it would seem prudent to perform a sentinel node biopsy prior to axillary clearance in order to confirm the presence of metastatic disease in histological specimens.

Learning points.

We observed the rare occurrence of extramedullary haematopoiesis in axillary lymph nodes after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced breast cancer where the initial aspirate suggested metastatic breast carcinoma.

Where there is diagnostic uncertainty from aspirate specimens, megakaryocytes should be considered as a benign differential diagnosis of metastatic carcinoma.

A sentinel node biopsy of nodes containing atypical cells such as multinucleate cells may be useful to confirm the presence of metastatic disease prior to axillary clearance.

The contribution of treatments such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor used in the neoadjuvant period may be aetiological in this case.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr Ruth Nash for her help in providing pathology images.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Millar E, Inder S, Lynch J. Extramedullary haematopoiesis in axillary lymph nodes following neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced breast cancer—a potential diagnostic pitfall. Histopathology 2009;2013:622–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zafar N. Megakaryocytes in sentinel lymph node—a potential source for diagnostic error. Breast J 2007;2013:308–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Guidance on cancer services: improving outcomes in breast cancer. London, UK: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Souza A, Jaiyesimi I, Trainor L, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor administration: adverse events. Transfus Med Rev 2008;2013:280–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith I, Heys S, Hutcheon A, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: significantly enhanced response with docetaxel. J Clin Oncol 2002;2013:1456–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chui A, Hoda R, Hoda S. “Pseudo-micrometastasis” in sentinel lymph node: multinucleated macrophage mimicking micrometastasis. Breast J 2001;2013:440–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher C, Hill S, Mills R. Benign lymph node inclusions mimicking metastatic carcinoma. J Clin Pathol 1994;2013:245–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Redmond J, Kantor R, Aueerbach H, et al. Extramedullary haematopoiesis during therapy with granulocyte colony-stimulation factor. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1994;2013:1014–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]