Abstract

We report a 61-year-old man presenting with rapidly progressive stiffness and painful muscle spasms in the lower extremity muscles. The patient was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) approximately a year before symptom onset. Electromyography displayed continuous motor unit activity and immunocytochemistry showed a positive staining for antiglycine receptor (anti-GlyR) antibodies. The clinical course was complicated by autonomic instability and cardiac arrest, but stabilised under continuous therapy with plasma exchange and symptomatic treatment with baclofen and clonazepam. Anti-GlyR antibodies induce rare, but severe, variants of stiff person syndrome that can be of paraneoplastic origin and life threatening due to autonomic dysfunction.

Background

Stiff person syndrome (SPS) is a rare, insidiously progressive disease of the central nervous system (CNS), characterised by stiffness and rigidity in the axial and proximal limb muscles with superimposed stimulus-sensitive spasms. In contrast, SPS does not lead to brainstem, pyramidal, extrapyramidal or lower motor neuron signs, sensory disturbance or cognitive impairment. SPS is considered to be part of a spectrum of related disorders, including stiff limb syndrome (SLS), jerking SPS and progressive encephalomyelitis with rigidity and myoclonus (PERM), which share clinical, laboratory, electrodiagnostic and histopathological features. Some patients can present initially with SLS and progress over a period of years to classical SPS and thence to PERM. The annual incidence of SPS and its variants was about 1 per million in the European population.1 2 On the basis of existing evidence, however, incomplete current consensus is that the underlying pathological process in SPS is indeed a humoral autoimmune response and that the autoantibodies found are pathogenic. Antiglutamic acid decarboxylase (anti-GAD) antibodies are present in serum or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of 60–80% of patients with SPS. SPS is strongly associated with other autoimmune diseases: about 35% of patients with SPS suffer from type 1 diabetes mellitus3 and about 5–10% of patients present with autoimmune thyroid disease, Graves’ disease, pernicious anaemia or vitiligo.4 However, other autoantibodies (antiamphiphysin antibodies, anti-Ri antibodies and antigephyrin antibodies) have been described in SPS including, most recently, antiglycine receptor (anti-GlyR) antibodies.5 6 Importantly, SPS and its variants have been associated in individual patients with tumour diseases such as breast cancer, multiple myeloma and Hodgkin's disease suggesting a paraneoplastic origin.5 The therapeutic approaches are focused on symptomatic therapy managing the muscle spasm (ie, benzodiazepines and baclofen) and on possible immunomodulatory procedures (intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), plasma exchange (PE) and depletion of mature cells by rituximab) to attenuate an autoimmune reaction. Patients with classic SPS usually respond well to treatment and their condition stabilises over time, although paroxysmal autonomic dysfunction or sudden death occurs in 10% of patients with SPS.5

Case presentation

A 66-year-old man was referred to our neurology department with a 4-week history of progressive stiffness and painful spasms of both legs, with recent worsening of his condition over the last 3 days resulting in a considerable difficulty to rise and to walk. There was no history of diabetes or other autoimmune diseases, but the patient was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) approximately 1 year before symptom onset with currently no need for treatment. The family history was unremarkable.

On admission, the lower limbs were rigid with fixated equinus position of the right foot. Movements were severely limited and painful, and strength could not be assessed because of rigidity and spontaneous, reflex-induced or action-induced spasms. The muscle spasms precipitated by sudden auditory or tactile startle as well as by psychological factors. A slightly increased tone was noted in his upper limbs, with normal muscular strength and without any movement limitation. No paraspinal or axial contractions were palpated. Sensory examination was normal except for reduced vibration sense in both lower extremities. Deep tendon reflexes were normal in the upper limbs. Patellar and Achilles jerks were markedly exaggerated. Plantar response was flexor bilaterally. Functionally, the patient was unable to walk because of rigidity in both of his legs. He had an intact intellect and there were no other psychiatric abnormalities.

Investigations

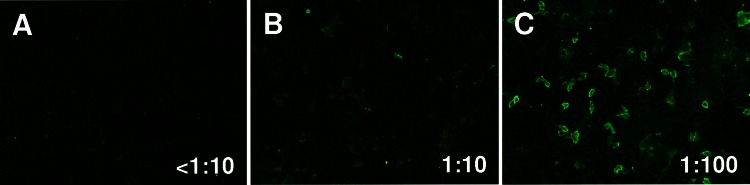

The results of the routine laboratory tests showed a mild pancytopenia (leucocytes 37.9×1000/µl, thrombocytes 112×1000/µl and haemoglobin 9.6 mg/dl). MRI of the whole neuroaxis and electroencephalography showed no additional findings. Electromyography revealed a persistent motor neuron activity most prominent in the lower extremity muscles which persisted despite the attempt to relax (figure 1). The peripheral nerve conduction velocities and amplitudes were normal. CSF examination showed a slightly increased cell count (10 cells/µl) and normal protein levels. A monoclonal population of lymphocytes was excluded in the CSF. Corresponding bands were found in CSF and serum. Screening for antineuronal antibodies anti-Hu, anti-Ri, anti-Yo, anti-CV2, antiamphiphysin, anti-Ma2 and anti-GAD antibodies in the patient's serum by indirect immunofluorescence assay showed no significant result. Still, with high suspicion that the clinical case could be SPS or a related syndrome, that is, SLS or PERM, we additionally screened the patients’ serum for anti-GlyR antibodies which were found positive, with a titre of 1 : 10 in the serum, but not in the CSF (figure 2). Owing to the clinically suspected paraneoplastic origin of the patients’ symptoms, we furthermore performed a thoracic, abdominal and skeletal CT scan which did not show any osteolysis or extramedullar manifestation of myeloma or any other malignoma.

Figure 1.

Electromyography. Continuous motor unit activity at rest detected in the right abductor hallucis muscle (A). Detection of a short myoclonic potential followed by a short tonic muscle contraction in the right abductor hallucis (B) and gastrocnemius muscle (C) after stimulation of the right peroneal nerve.

Figure 2.

Indirect immunofluorescence assay. Detection of anti-glycine receptor antibodies stained by indirect immunofluorescence, in a serum sample from our patient (B), compared with negative control (A) and positive control (C).

Treatment

The first therapeutic approach was aimed at symptom relief with the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonists baclofen and clonazepam. The combination of both medications provided a relatively modest relief of the patients’ excessive motor unit activity. With regard to the patient's underlying disease (ie, CLL) as the suspected origin of the symptoms, we started a therapy with rituximab and bendamustine (first day rituximab 350 mg/m², second and third day bendamustine 90 mg/m²) which causes a depletion of mature B cells. A second treatment course was given 12 weeks later. At 2 days after the second course, the patient developed a severe autonomic instability (profuse sweating, mydriasis, tachycardia, high blood pressure and hyperthermia) followed by a cardiac arrest. He was resuscitated and ventilated and further treated on our intensive care unit, where a therapeutic trail with IVIG was started. The patient did not show any improvements neither in stiffness nor in myoclonic jerks 7 days after the initiation of IVIG treatment.

Outcome and follow-up

Only after five cycles of PE, a significant relief of myoclonic jerks was achieved. Under continuous therapy with PE every 3 months and symptomatic treatment with baclofen and clonazepam, the patient was in a stable condition, bed-bounded, but without severe impairment owing to painful muscle rigidity and spasms.

Discussion

Our case illustrates an example of rapidly progressive SLS with its most prominent manifestation seen in the lower extremity muscles. A key feature of our patient’s symptoms was the occurrence of muscle spasms that were preceded by sudden movement, loud noise or emotional stress as described in the literature as startle reaction.6 In serological analysis, anti-GlyR antibodies were found to be positive. The clinical course of the disease was complicated by autonomic instability followed by a cardiac arrest. Under continuous therapy with PE and symptomatic treatment with GABA agonists, the patient was brought in a stable condition.

The stiffness in our patient was most pronounced in the distal portion of his legs. While this is typical for SLS, muscle stiffness sometimes progresses to involve the axial musculature as well.2 SLS differs from classic SPS in that the latter involves preferentially paraspinal and abdominal muscles typically leading to hyperlordosis, and rarely if ever, the foot is affected.7 8 The fact that anti-GAD antibodies and autoimmune diseases are absent is not unusual. Most patients with SLS do not have antibodies against GAD. Positivity for anti-GlyR antibodies has been reported in patients with SLS with lower frequency than in PERM and SPS.9 10

Rigidity and spasms are often preceded or accompanied by sensory symptoms or brainstem signs of ataxia, vertigo, disturbances of ocular motility and dysarthria in patients suffering from PERM. All these additional symptoms were definitely not present in our patient, so we clinically excluded the diagnosis of PERM in our patient.

Considering the patient’s history of CLL, a paraneoplastic origin needs to be discussed. In fact, the short duration of disease argues against SLS (long clinical disease course) and rather hints on a neoplastic or paraneoplastic aetiology.

CNS involvement of CLL remains a poorly studied phenomenon in the literature and occurs with an incidence of 0.8–2%.11 Reported cases of CNS involvement of CLL have demonstrated a diverse and non-specific spectrum of symptoms: headaches, acute or chronic changes in mental status, cranial nerve abnormalities, optic neuropathy, weakness of lower extremities and cerebellar signs. SPS or one of its variants has not been described to be a neoplastic or paraneoplastic phenomenon of CLL yet. Instead, an association of SPS with solid tumours (ie, thymoma and breast cancer) and, more rarely, with haematological malignancies is well established. The negativity of CSF cytology and the normal cranial MRI studies as well as the fact that the patient's symptoms did not improve to chemotherapy with rituximab and bendamustine do not rule out a neoplastic or paraneoplastic cause of the symptoms. Still, clinicians need to think of the possibility early on and a thorough work-up to rule out CLL as the cause of neurological symptoms is required.

Learning points.

The rarity of stiff limb syndrome (SLS) and the elusive clinical signs make its accurate diagnosis difficult.

Antiglutamic acid decarboxylase-negative patients may show other autoantibodies which are even rarer.

The rate of clinical progression of the disease and the occurrence of systemic complications including autonomic failure render SLS a potentially life-threatening disease.5

In order to prevent such complications, a rapid diagnosis, an early beginning of immunomodulatory treatment, as well a close-meshed monitoring of vital signs and early surveillance on intensive care unit are mandatory.

Footnotes

Contributors: AD contributed to study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, statistical analysis, drafting the manuscript and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. MS was involved in acquisition of data and, analysis and interpretation of data and electromyography analysis. WS was responsible for immunocytochemical studies of antibodies in the patient’s serum. RJS contributed to study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and study supervision.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Koerner C, Wieland B, Richter W, et al. Stiff-person syndromes: motor cortex hyperexcitability correlates with anti-GAD autoimmunity. Neurology 2004;2013:1357–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meinck HM, Thompson PD. Stiff man syndrome and related conditions. Mov Disord 2002;2013:853–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalakas MC. Stiff person syndrome: advances in pathogenesis and therapeutic interventions. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2009;2013:102–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solimena M, Folli F, Aparisi R, et al. Autoantibodies to GABA-ergic neurons and pancreatic beta cells in stiff-man syndrome. N Engl J Med 1990;2013:1555–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gershanik OS. Stiff-person syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2009;2013(Suppl 3):S130–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown MJ. Electrodiagnosis in diseases of nerve and muscle. Ann Neurol 1990;2013:201 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barker RA, Revesz T, Thom M, et al. Review of 23 patients affected by the stiff man syndrome: clinical subdivision into stiff trunk (man) syndrome, stiff limb syndrome, and progressive encephalomyelitis with rigidity. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;2013:633–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown P, Rothwell JC, Marsden CD. The stiff leg syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997;2013:31–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown P, Marsden CD. The stiff man and stiff man plus syndromes. J Neurol 1999;2013:648–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mas N, Saiz A, Leite MI, et al. Antiglycine-receptor encephalomyelitis with rigidity. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011;2013:1399–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanse MC, Van't Veer MB, van Lom K, et al. Incidence of central nervous system involvement in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and outcome to treatment. J Neurol 2008;2013:828–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]