Abstract

We report a 49-year-old man with alcoholic severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) complicated by drug-induced acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (DI-AIN). Oliguria persisted and became anuric again on day 17 despite improvement of pancreatitis. He presented rash, fever and eosinophilia from day 20. Renal biopsy was performed for dialysis-dependent acute kidney injury (AKI), DI-AIN was revealed, and prompt use of corticosteroids fully restored his renal function. This diagnosis might be missed because it is difficult to perform renal biopsy in such a clinical situation. If the patient's general condition allows, renal biopsy should be performed and reversible AKI must be distinguished from many cases of irreversible AKI complicated by SAP. This is the first report of biopsy-proven DI-AIN associated with SAP, suggesting the importance of biopsy for distinguishing DI-AIN in persisting AKI of SAP.

Background

The incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) complicating severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) ranges from 14–42%, and mortality remains high at 58–74.7% despite enhanced intensive care unit (ICU) treatment.1 AKI is mostly preceded by multiple organ failure1 2 and renal biopsy is difficult to perform because of the generally poor condition of the patient. The mechanism of AKI occurring in SAP remains unclear, although a number of factors may be involved. It can be due to acute tubular necrosis (ATN) caused by hypovolemia, sepsis or intravascular coagulation.3 Interestingly, despite many factors having been reported, there has been no recorded case with acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (AIN). AIN also proceeds to renal failure but is reversible with appropriate treatment.4

To our knowledge, there have been only three other reports of SAP with AKI and renal biopsy,5–7 all bilateral acute cortical necrosis as a result of SAP, and none with drug-induced acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (DI-AIN) complication. By performing the biopsy, we actually clarified the causes of kidney failure complicated with SAP in this case. In terms of being based on tissue diagnosis, this is the first, strongly suggestive report of DI-AIN concurring with SAP.

Case presentation

A 49-year-old man was admitted with a sudden attack of upper abdominal pain and vomiting. He was a heavy drinker and had consumed 25 glasses of beer through the day. He noticed general malaise and loss of appetite 1 month before admission. He had no particular history, known allergies or familial histories.

The patient was alert and oriented, with blood pressure 85/71 mm Hg, pulse 89/min regular and body temperature 36.6°C. Epigastric tenderness without muscle defence was noted. He showed anuria. No further peculiarities were found.

Investigations

Laboratory test results were: haemoglobin 14.9 g/dl, white blood cell count 11 600/mm3 with normal differential, platelet count 297 000/mm3, serum lipase 1 620 IU/l (normal 11–53 IU/l), pancreatic amylase (P-amylase) 339 IU/l (normal 20–65 IU/l), urea nitrogen 16 mg/dl, creatine 0.96 mg/dl, sodium 141 mEq/l, potassium 3.6 mEq/l, calcium 8 mg/dl, alkaline phosphatase 1 043 IU/l, γ-glutamyltranspeptidase 2 107 IU/l, aspartate aminotransferase 224 IU/l, alanine aminotransferase 124 IU/l, total bilirubin 0.9 mg/dl, C reactive protein (CRP) 0.10 mg/dl and prothrombin time 11.6 s (normal 10–13 s). Arterial blood gases (room air) revealed pH of 7.41, PaCO2 32.6 torr, PaO2 89.2 torr, base deficit −3.0 mEq/l. The urine dipstick showed 1+ for protein and—for haemoglobin. The sediment contained 0–1 red cells, 0–1 white cells and no casts or crystals. The urine β2-microglobulin (β2-MG) was 267 μg/dl (normal <260 μg/dl).

Abdominal contrast-enhanced CT demonstrated diffuse pancreatic enlargement, peripancreatic fat and peripancreatic fluid collection (CT severity index: grade D). No pancreatic duct dilation or gallstones were seen. The diagnosis was acute pancreatitis. Both kidneys were normal in size with no stones.

Aggressive treatment in the intensive care unit (ICU) consisted of protease inhibitor, imipenem/cilastatin (IPM/CS), ulinastatin and intravenous fluid replacement. He recovered from hypovolemic shock immediately. Follow-up examinations performed 15 h later revealed progression of pancreatitis: P-amylase 519 IU/l, urea nitrogen 27 mg/dl, creatine 2.81 mg/dl, calcium 5.7 mg/dl, base deficit −6.7 mEq/l, total resolution of pancreatic fluid and total resolution of extravasated fluid around the gland on CT scan (CT severity index: grade E). Continuous regional arterial infusion therapy (IPM/CS at 0.5 g/day and nafamostat mesylate at 250 mg/day for 5 days via caeliac and superior mesenteric arteries) and selective digestive tract decontamination (amphotericin b) were performed. Anuria persisted, being refractory to adequate fluid replacement therapy. Continuous haemodiafiltration (CHDF) was started 18 h after hospitalisation for AKI. Serum CRP and P-amylase levels then decreased rapidly and urine output increased on day 2.

Despite improvement in pancreatitis, urine output did not return to normal and dropped again to almost 0 ml/day on day 17 (figure 1). Because his general condition improved except for renal function, CHDF was switched to haemodialysis on day 16. On day 18, his body temperature had risen to 39°C. On day 20, widespread maculopapular rash, elevated eosinophil count (figure 1) and a marked increase in immunoglobulin E (IgE) level (734 IU/ml (normal 0–20 IU/ml)) were noted. They strongly suggested that severe systemic allergic reaction had occurred. Although urine output was below 10 ml/day, urine tests revealed urinary eosinophils >40% (normal <1%) and drastic increase of urine β2-MG (35 770 µg/dl), indicating that strong tubulointerstitial inflammation had merged over and above the initial renal injury.

Figure 1.

Serial changes of serum creatine, eosinophil count, urine volume and urine β2-microglobulin.

Differential diagnosis

The cause of anuria at first point was thought to be prerenal related with hypovolemic shock. Aggressive fluid replacement therapy was performed and urine output increased, but oliguria sustained and became anuric again on day 17 (figure 1). Fractional excretion of sodium was 2.01% on day 17, suggesting that prerenal azotemia was unlikely to be the cause of additional renal injury. In addition, there was no hypovolemic state once after it had been corrected. Therefore, we suspected that another cause for anuria might have occurred over and above the existing renal injury, likely ATN.

Postrenal factor such as urinary tract obstruction was excluded by CT scan. As one of the renal factors, contrast-induced nephropathy might have occurred in this case, but it was thought to be atypical in terms of the course of renal failure (typical recovery 3–5 days). Systemic maculopapular rash, fever, eosionophilia, elevated IgE levels and increased urine β2-MG were observed, all helping to point us toward DI-AIN, but they have limited diagnostic utility. Renal biopsy is the only definitive diagnostic test for DI-AIN.

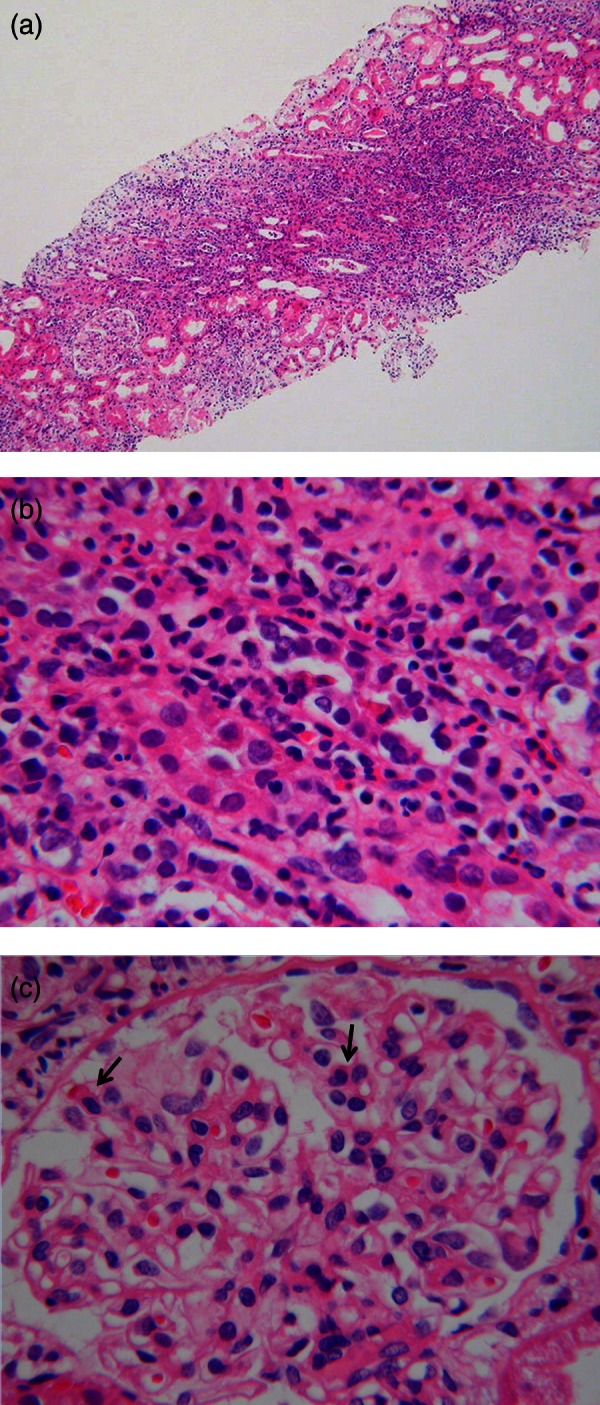

We performed renal biopsy in the ICU on day 29. Light microscopy showed 13 glomeruli, one being globally sclerosed, but the others were unremarkable. Diffuse interstitial mononuclear cell infiltration admixed with neutrophils and a massive infiltration of eosinophils into the interstitium were observed (figure 2). The morphological form of renal tubules and arterial vessels were relatively conserved, strongly suggesting that not tubular necrosis but AIN had occurred. An immunofluorescence panel was negative and electron microscopy revealed unremarkable glomeruli with no evidence of deposits, consistent with AIN (data not shown). It also indicated that acute nephritis or arterial embolism were negative.

Figure 2.

H&E staining of the renal biopsy specimen by light microscopy. (A) Low magnification field shows diffuse interstitial, predominantly mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates. (B) Higher magnification field reveals prominent eosinophilic infiltration invading the tubular lumen and tubulitis with oedema. (C) Glomeruli shows endocapillary proliferative changes with a few eosinophils (arrows).

The distribution of causes of AIN has been reported; drugs in more than 75%, infections in 5–10 %, tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome in 5–10% and systemic disease including sarcoidosis, Sjoegren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus in 10–15%.8 Infections, TINU syndrome and systemic disease were thought to be negative from clinical signs, investigations and the results of renal biopsy, leading us to conclude that DI-AIN had merged.

Treatment

Among drugs known to be associated with AIN, he had been given rabeprazole, famotidine and ciprofloxacin hydrochloride (CPFX); all of them were stopped.

Standard treatment of DI-AIN is discontinuation of suspected drugs and early use of steroid therapy. It was difficult to use steroid without hesitation under the situation of severe acute pancreatitis because the risk of infection was high, but we had the definitive diagnosis of DI-AIN by renal biopsy which gave us a supportive push forward. High-dose pulse intravenous steroids (0.5 g of methylprednisolone for 3 days) and a course of oral prednisolone (PSL, 0.8 mg/kg/day) were started from day 29, and then rapidly tapered from day 40 by 5 mg every 5 days.

Outcome and follow-up

Renal function improved immediately, and he was discharged with normal kidney function on day 67.

Drug-induced lymphocyte stimulation tests (DLSTs) were performed after the withdrawal of PSL, and the results for rabeprazole, famotidine and CPFX were all negative.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report of DI-AIN developed over and above the existing renal injury caused by SAP.

AKI is a common complication of SAP, mostly preceded by other organ system failure; the prognosis is extremely poor.1–2 In contrast, AIN is a major cause of reversible AKI that should be accurately and promptly diagnosed. AKI often occurs in SAP, and DI-AIN might set in, but it is difficult to distinguish without extrarenal manifestations. Furthermore, allergic reactions are common in the ICU, making it difficult to recognise the triad as extrarenal manifestations of DI-AIN particularly in cases with anuria.9

Our patient showed anuria from the point of hospitalisation. The most probable cause of the initial renal dysfunction could be related to a haemodynamic origin due to hypovolemic shock. ATN might have occurred, but tubular necrosis was not observed in the biopsy specimen. Patients with ATN without other organ system failure usually recover renal function in 7–21 days,10 so renal biopsy is reserved for cases with delayed renal recovery. The patient was dependent on renal replacement therapy by his oliguria and became anuric again on day 17. On day 20, he showed rash, fever and eosinophilia, helping to point us toward DI-AIN.

Renal biopsy is the only way to confirm this diagnosis, with typical histopathological findings of infiltrates showing mostly T cells, some macrophages, plasma cells and eosinophils. Eosinophiluria was found in our patient with anuria, but it was hard to evaluate because it could also occur in other conditions such as pyuria.11 Non-invasive tests such as 67Ga scintigraphy and eosinophiluria have limited diagnostic utility.12 However, the performance of renal biopsy is technically difficult in almost all cases of SAP because of their generally poor condition. We succeeded in performing renal biopsy in the ICU and confirmed the diagnosis of DI-AIN.

The most frequently implicated drugs in the development of DI-AIN are antibiotics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, but fluoroquinolones-associated AIN has also been reported in 30 cases.13 Renal manifestations develop within 3 weeks (average delay about 10 days) after starting the inciting drug in about 80% of patients. In our case, eosinophilia and dropped urine output were observed about 14 days after the initial administration of CPFX, suggesting that this was the most likely offending agent. All suspected drugs were ceased, based on the fact that there is widespread agreement about discontinuation of the offending drug as the first therapeutic step of DI-AIN. As indicated above, DLSTs for suspected drugs were all negative, but the sensitivity of DLST is as low as 60% (mainly based on β-lactam hypersensitivity analysis),14 perhaps not enough to exonerate CPFX as the guilty drug.

Recent reports have suggested a beneficial role for corticosteroids, and their earlier application seems to coincide with better renal function recovery.15 However, approximately one-third of the patients with pancreatic necrosis develop infected necrosis with its occurrence leading to morbidity and mortality in acute necrotising pancreatitis.16 Therefore, we needed to deny other steroid-refractory or irreversible pathogenesis and be careful while using steroids in SAP patients. In our case, we succeeded in performing renal biopsy to confirm the diagnosis, and prompt use of corticosteroids and appropriate infection control measures then fully restored renal function. In this sense, the presence of a nephrologist in the care team may be needed to provide another insight for a prompt resolution.

Many drugs are used to treat SAP and renal dysfunction is always a possibility, DI-AIN as a complicating disease may be easy to miss. Moreover, when renal replacement therapy is used, as is often the case in critically ill patients, reaching a diagnosis becomes more difficult. But as in this case, if possible, renal biopsy will prevent missing the presence of reversible AKI.

In conclusion, this report suggests the importance of distinguishing DI-AIN in patients with persistent AKI on SAP.

Learning points.

Remember that reversible acute kidney injury (AKI) such as drug-induced acute tubulointerstitial nephritis might be hidden in cases of AKI on severe acute pancreatitis (SAP), especially when renal replacement therapy is used.

If the general condition allows, renal biopsy would prevent oversight of reversible AKI.

Presence of a nephrologist in the care team of critically ill patients may provide another insight toward the resolution.

Acknowledgments

We deeply appreciate Dr Hiroyuki Tanaka for his critical review of the manuscript. We are also grateful to Dr Naoko Yamamoto, Dr Takaaki Ikeda for their revision of patient management; Dr Yukio Tsuura for the assessment of the histology; Dr Shintaro Mandai, Dr Toshiyuki Hirai, Dr Daiei Takahashi, Dr Shota Aki and Dr Makoto Aoyagi for their kind assistance throughout the preparation of the figures and this report.

Footnotes

Contributors: WK and TM were involved in the management of the patient. TT supervised the management of the patient. WY, TM and TT carried out the renal biopsy of the patient. KN carried out the pathological investigation of the patient. All authors contributed equally in writing and preparing the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hao L, Zhaoxin Q, Zhiling L, et al. Risk factors and outcome of acute renal failure in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. J Crit Care 2010;2013:225–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tran DD, Oe PL, Fijter CWH, et al. Acute renal failure in patients with acute pancreatitis: prevalence, risk factors, and outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1993;2013:1079–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imrie CW. Observations on acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg 1974;2013:539–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricketson J, Kimel G, Spence J, et al. Acute allergic interstitial nephritis after use of pantoprazole. CMAJ 2009;2013:535–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alfonzo AV, Fox JG, Imrie CW, et al. Acute renal cortical necrosis in a series of young men with severe acute pancreatitis. Clin Nephrol 2006;2013:223–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slater G, Goldblum SE, Tzamaloukas AH, et al. Renal cortical necrosis and Purtscher's retinopathy in haemorrhagic pancreatitis. Am J Med Sci 1984;2013:37–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Churgh KS, Jha V, Sakhuja V, et al. Acute renal cortical necrosis—a study of 113 patients. Ren Fail 1994;2013:37–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manuel P, Gerald BA. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of acute interstitial nephritis. In: Basow DW, ed. Up To Date. Waltham, MA: Up To Date, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanji S, Chant C. Allergic and hypersensitivity reactions in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2010;2013(6 Suppl):162–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myers BD, Moran SM. Hemodynamically mediated acute renal failure. N Engl J Med 1986;2013:97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruffing KA, Hoppes P, Blend D, et al. Eosinophils in urine revisited. Clin Nephrol 1994;2013:163–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perazella MA, Markowitz GS. Drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2010;2013:461–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hadimeri H, Almroth G, Cederbrant K, et al. Allergic nephropathy associated with norfloxacin and ciprofloxacin therapy. Report of two cases and review of the literature. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1997;2013:481–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luque I, Leyva L, Torres MJ, et al. In vitro T-cell responses to β-lactam drugs in immediate and nonimmediate allergic reactions. Allergy 2001;2013:611–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kodner CM, Kudrimoti A. Diagnosis and management of acute interstitial nephritis. Am Fam Physician 2003;2013:2527–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banks PA, Freeman ML, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;2013:2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]