Abstract

Osseous hydatidosis is a very severe and recurrent complication of hydatidosis. The two cases reported here illustrate the severity of this invasive and destructive osseous parasitosis located at the femur and the hip joint, which required extensive resection and prosthetic reconstruction. The first case had a long history of liver and lung hydatidosis with a wide ‘en-bloc’ extra-articular resection of the right hip joint including the proximal femur; the second case had an ‘en-bloc’ total femur resection and total femur prosthesis. Preoperative and postoperative chemotherapy with albendazole was combined with surgery and was applied for many months. These two cases occurred several years after the incomplete treatments of recurrent lung or liver hydatidosis and might have been prevented if chemotherapy had been initially applied.

Background

Hydatidosis is a human parasitosis caused by the larval form of the dog tapeworm: Echinococcus granulosus. It occurs mainly in rural areas, particularly where large herds of sheep are controlled by sheepdogs. In endemic areas such as the Middle East, Central Asia, South America, East Africa and Turkey,1 2 hydatidosis is relatively common, particularly when hygiene is poor, and mainly affects individuals in close contact with sheepdogs (children, farmers, shepherds and veterinarians).

E granulosus is a small tapeworm about 5 mm in length and is composed of a head (called scolex) and a body (called strobila).2–4 The adult tapeworm lives in the small bowel of the host (dogs and other canines) attached by its scolex to the villi and produces infectious eggs excreted in the faeces. The usual intermediate hosts (sheep, goats, camels, etc) as well as humans become infected after ingesting these eggs. After ingestion, the embryos migrate through the intestinal wall and enter the portal circulation. Larvae will reach the liver and lungs as the first filters, and thereafter may settle in any organ and develop into hydatid cysts that can survive for several months or even years. Larvae are found in the liver in 75% of all cases and in the lung in 15% of cases, with 10% of cases involving other organ systems.5 6 The size of the hydatid cyst depends on its age and may reach 20 cm or more. It contains a clear, sterile, hydatid fluid and a huge number of protoscoleces. Occasionally, the larvae can migrate into bones and this location accounts for 0.5–4% of E granulosus cases in humans.4 7 8 The spine is the most common site of osseous hydatidosis (50% of cases),7 9 10 followed by the pelvis and hip.2 7 9 11 Other sites of infection include the femur, tibia, fibula, ribs, scapula, clavicle and tarsal bones.1 6 9 12–15 Osseous hydatidosis is considered as a very severe and recurrent complication of hydatidosis, as illustrated by the two cases reported here, where invasive and destructive osseous hydatidosis of the femur and the hip joint needed extensive resection and prosthetic reconstruction. The literature is reviewed and the medical treatment is discussed.

Case 1

A 45-year-old man was referred to our department in January 2009. He was complaining of a right thigh pain. He was limping and walking with the aid of a crutch. The patient had a long history of hydatidosis. This patient was born in France; when around 20 years of age; he spent 2 years in North Africa doing his military service; and during this period he had a lot of contact with stray dogs. Ten years later; the patient experienced swelling and pain in his left clavicle. This supraclavicular cystic mass was resected in another institution. Histology revealed the presence of E granulosus within the excised tissue. At that time, a CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis revealed the presence of a cyst within the liver. The hepatic cyst was removed by laparotomy. Histological examination was also positive for E granulosus. He had no other treatment and no follow-up. Twelve years later, he experienced a persistent cough associated with thoracic pain and an episode of haemoptysis. Investigations (chest x-ray and CT scan) revealed a pulmonary cyst. The cyst was surgically excised and the histology again confirmed the presence of E granulosus. Once again, no specific treatment by albendazole was given and no follow-up was organised. A few months later, groin swelling and painful hip motivated him to present to a different hospital, where osseous hydatidosis was diagnosed. The patient was prescribed 800 mg albendazole, but no surgery was proposed. After 18 months, the patient was referred to our outpatient clinic for persistent and increasing pain in the right thigh. Anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the pelvis showed a thinned and eroded medial cortex of the proximal right femur. Punctuated osteolysis was seen in the right greater trochanter and the coxofemoral joint showed a concentric narrowing. The anterior and superior compartment of the femoral head also showed partial collapse (figure 1A). MRI of the right hip showed that the lesion involved the first 14 centimetres of the proximal femur, including the femoral head and neck, the metaphysis and the proximal part of the diaphysis (figure 1B). The hip-joint and entire acetabulum were invaded by the cystic lesion. The only extraosseous component of the lesion developed within the vastus lateralis and rectus femoris and presented as an intramuscular cyst. A small cystic lesion had also developed into the gluteus minimus and in contact with the tip of the greater trochanter. Gluteus medius and maximus muscles were intact. Blood tests showed a positive serology for E granulosus (ELISA and Western-blot). Chemotherapy was started associating 2×400 mg of albendazole and 3×600 mg of praziquantel a day. The patient was scheduled for a surgical procedure and asked to stop weight-bearing on the right lower limb.

Figure 1.

(A) Plain anteroposterior x-ray of the right hip joint of case 1. The x-ray reveals a severe arthritis of the joint and an extensive heterogeneous osteolysis of the proximal femur. Both medial and lateral cortices are thinned and the greater trochanter presents a prefracture pattern. A malignant tumour-like process was suspected. (B) T1-weighted MRI in the frontal plan of the right hip revealing a tumour-like process of the entire proximal femur and extending to the hip joint and to the acetabulum of the right iliac bone. Extension to the surrounding soft tissues is not visible on this image. (C) Plain anteroposterior x-ray of the pelvis and both femurs of case 1 at the last follow-up. The proximal femur and the affected part of the iliac bone have been resected. The hip joint has been replaced by a ‘saddle hip prosthesis’ with a long femoral stem.

Considering the extension of the lesion and the high potential for recurrence, a total extra-articular resection of the right hip joint including the proximal femur was performed. A double surgical procedure was used by combining a Kocher-Langenbeck posterior approach and an ilio-femoral anterior approach to the right hip and pelvis. The gluteus maximus and gluteus medius muscles were preserved, and an ‘en-bloc’ hip arthrectomy was performed resecting in continuity the acetabulum, the proximal femur and the two cystic lesions invading the gluteus minimus posteriorly, the vastus lateralis and rectus femoris anteriorly. After intense and meticulous lavage, a reconstruction of the hip joint was performed using massive cemented total hip replacement prosthesis (so-called ‘Saddle prosthesis’) with a proximal femur allograft (figure 1C). The allograft allowed the reinsertion of the abductors muscles of the hip. Macroscopic sections of the removed lesion showed the infiltration of the spongy bone by a large intradiaphyseal cyst and by numerous small vesicles in the femur head and the retro-cotyloid region of the pelvic bone (figure 2). Histological examination of the excised tissues showed a typical lamellar structure confirming the presence of E granulosus. The parasite was genotyped by cytochrome oxidase amplification and sequencing and identified as belonging to the common gastrointestinal genotype. Albendazole was associated with praziquantel continuously for 6 weeks postoperation, and once in every 2 months for another 18 months. The period immediately after the operation was uneventful; the patient was painless and was able to walk with a crutch outdoors. Twenty-six months post operatively, the patient came back to our department presenting pain in the right lower limb. AP radiograph of the femur revealed a loosening of the stem and showed osteolytic changes in the proximal part of the remaining femur. Local recurrence of the hydatid disease was highly suspected. Albendazole chemotherapy was increased (3×400 mg three times a day) associated for 1 month to 3×600 mg of praziquantel daily. Praziquantel was stopped because of digestive intolerance and increased levels of seric γ-glutamyl transferase (GT). A revision surgery was scheduled. The ‘Saddle prosthesis’ was changed for a longer femoral stem. Curettage of the proximal part of the remaining femur was performed and pathological tissues mimicking false membranes were excised. There were no macroscopically identifiable cystic lesions and the surrounding muscles were intact. Before inserting the new stem, abundant lavage using hypertonic serum was performed. Postoperation, the patient showed a quick recovery. Histological examination of the excised tissues confirmed the recurrence showing typical lamellar membranes. Twelve months after the revision surgery, the patient was doing well, walking with one crutch. The patient is aware of the risk of a new recurrence and has remained under albendazole therapy at 4×400 mg three times a day with a monthly checking of blood cells counts and liver enzymes. Seric levels with this dosage comprised between 0.4 μmol/l (just before intake) and 1.5 μmol/l (4 h after intake). No significant modification of antibody titres was noticed during the 3 years of follow-up.

Figure 2.

Macroscopic aspect of the lesion removed from case 1. The femur diaphyseal medulla is filled with a cyst. The spongy bone is infiltrated by small vesicles. A section of the retro-cotyloid region of pelvic bone also shows several yellowish vesicles.

Case 2

A 32-year-old Turkish woman was referred to our department because of pain in the left groin radiating to the anterior region of the left thigh. In her medical history, she had a cervical lipoma removed in 2003 and liver hydatid cysts removed in 2000 and 2004 without subsequent albendazole therapy. The groin pain had been present for 4 years, but remained intermittent and moderate in intensity. Her general practitioner suggested several times that she should consult a rheumatologist, but without success. The patient was otherwise healthy and her clinical examination showed a normal range of motion of both hips with no local swelling. Radiographic analysis of the hip showed an osteolytic lesion developing within the proximal part of the left femur. The lesion developed within the intertrochanteric region and extended to the proximal third of the diaphysis. Medial and lateral diaphysal cortices were partially eroded and thinned. The osteolysis was associated with cystic-like sclerotic rims. The intertrochanteric region appeared widened when compared with the contralateral femur. The femoral head and neck were intact. Finally, another osteolytic lesion was present in the distal part of the left femur. This osteolysis developed on the medial aspect of the distal femoral metaphysis and partially eroded the medial cortex. The radiographic aspect was compatible with a fibrous dysplasia (figure 3A, B). MRI showed high signal intensity in the entire femoral shaft. A CT-guided biopsy was performed and histological analysis found non-specific necrotic tissue with no evidence of malignancy or fibrous dysplasia. The patient was then treated with bisphosphonates in order to enhance local bone density. A few weeks later, the patient experienced a sudden excruciating pain in the left femur after getting out of her car. Radiographs revealed a pathological femoral shaft fracture of the left femur (figure 3C). A transtibial traction stabilised the fracture and a surgical biopsy was performed the next day. Hooks and protoscoleces of E granulosus were seen by the unstained microscopic examination of the removed tissues. Histological analysis showed laminated layers surrounded by a cellular infiltrate composed of polymorphonuclear neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells (figure 4). Specific antibodies were detected both by ELISA and western blot. A CT scan of the brain, chest, abdomen and pelvis failed to detect other locations of the disease. Considering (i) the extension of the hydatid lesions within the diaphysis of the patient's femur (two-thirds of the femur) and (ii) the high potential for recurrence of this parasitic disease, the only surgical procedure with a reasonable chance of success was to remove the entire left femur. ‘En-bloc’ total femur resection was performed and a total femur endoprosthesis was used to replace the patient's femur (figure 3D). The period immediately following the operation was uneventful and the patient was transferred to the rehabilitation centre. Chemotherapy by albendazole (3×400 mg three times a day) was administered for 6 weeks preceding surgery and is still being prescribed. Albendazole seric assays showed significant levels 3 h after intake (3 μmol/l). On the last follow-up, 18 months after the surgical procedure, the patient is doing well with no evidence of recurrence or infection. She is walking with one crutch with 1 h autonomy.

Figure 3.

Plain x-ray ((A) anteroposterior (AP) view; (B) lateral view) of the left hip joint of case 2. The left femur has a heterogeneous bone lesion developed in the proximal metaphysis and the proximal third of the diaphysis. The association of cortical thinning, osteolysis and cystic rims is compatible with the diagnosis of fibrous dysplasia. (C) AP x-ray of the left hip of the same patient showing a displaced pathological subtrochanteric fracture of the affected femur. (D) Plain AP x-ray of the left hip joint and femur. The whole femur has been resected and replaced by a total femur endoprosthesis.

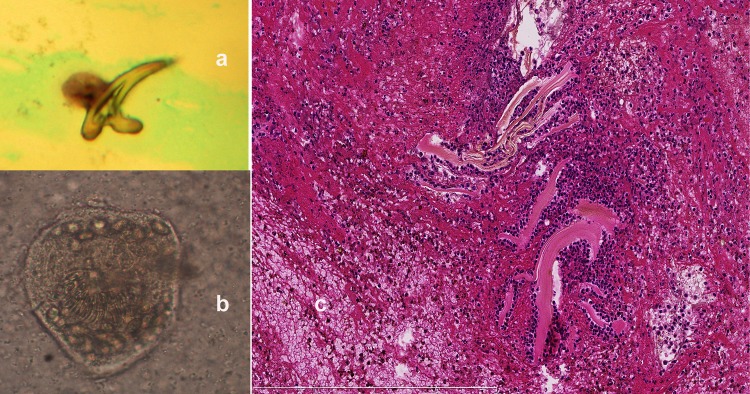

Figure 4.

(A) Hook observed by microscopic examination of the biopsy performed in case 2. (B) Unstained Echinococcus granulosus protoscoleces observed by microscopic examination of the biopsy performed in case 2. (C) Formalin-fixed material stained by HES showed laminated layers surrounded by a cellular infiltrate composed of polymorphonuclear neutrophils and eosinophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells. HES, hematoxylin and eosin stain.

Discussion

These two cases illustrate well the severity and the difficulties encountered in treating bone hydatidosis, which can be compared with a malignant lesion. When infiltrating bones, vesicles of various sizes develop into the cancellous part of the affected bone and easily spread into the medullary canal. Articular cartilage and intervertebral disc may also be invaded by cystic proliferation. Erosion of the cortical bone may also occur and the disease may expand to the neighbouring structures such as joints and muscles. Three principle mechanisms of bone destruction have been described: compression, local ischaemia and osteoclast proliferation.1 Bone hydatidosis usually remains asymptomatic for a long period since the infiltrating cysts grow slowly. When diagnosis is made, bone lesions are often already extensive. Pain, swelling and pathological fracture usually reveal bone hydatidosis.12 16 Neurological symptoms are not rare when the lesion is located in the spine.5 17 Hydatid bone lesions are frequently misdiagnosed unless there are strong elements of suspicion in the medical history of the patient. Radiographic and CT findings are unspecific and heterogeneous and may mimic either benign or malignant bone tumours. Several differential diagnoses can be cited: fibrous dysplasia, giant-cell tumour, aneurysmal bone cyst, enchondroma, bone tuberculosis, chondrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, myeloma and metastatic disease.1 2 6 8 11 12 The typical radiographic appearance of bone hydatidosis is reported to show multilocular cystic lucencies with bone expansion and cortical thinning with a reactive sclerosis that gives the bone a honeycomb appearance.1 2 18 The sero-diagnosis (ELISA and western blot) confirms the diagnosis in contrast to other cystic locations (liver, lung) where serology can be negative. The principal factor related to a positive serology is the presence or absence of complications (rupture and infection/abscess) owing to the release of parasite antigens.19 Most of the literature describes lower sensitivity of serology in lung hydatidosis compared with liver hydatidosis, but more recent studies with more sensitive assays seem to find similar proportions of seropositive individuals.20 Bony hydatid lesions are associated with a 50% rate of local recurrence.21 The rate of recurrence is also significant in extraosseous hydatid disease. Haralabidis et al have reported an 11.4% rate of relapse after surgical excision in a series of 70 patients with recurrences occurring within the first 6 months after the end of chemotherapy. They also report that, at 8.5 years of follow-up, all patients were free of disease.22 The recommended treatment for hydatid cysts is a radical surgical excision combined with adjuvant preoperative and postoperative chemotherapy in order to prevent recurrence.4 23 The combination of albendazole and praziquantel may improve the therapeutic efficacy as a consequence of higher active concentration of both drugs. On the other hand, this association may increase the risk of side effects, thus raising the question about reduction of the dosage of each drug.24 The role and length of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy in musculoskeletal hydatid disease is unclear. In case 1, praziquantel chemotherapy induced abdominal discomfort and intolerance and provoked increased seric levels of γ-GT. Adjunction of a third drug (nitazoxanide), as advocated in the oral treatment of hydatid disease, does not appear to be a good option as nitazoxanide is not active in bone tissue.25 However, further studies are necessary to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the drug associations on the long term.

Considering the high potential of recurrence, radical surgical excision of the parasitic lesion has to be performed. The principles of malignant bone tumour excision apply to hydatid bone lesions and wide-health margins are mandatory to reduce the risk of recurrence. Radical resection in the pelvis and hip is most challenging. In the two cases reported here, the hydatid disease had spread largely into the femoral shaft and/or hip joint and large resections were performed. Unfortunately, in case 1, the resection was not radical enough at the first procedure. Gross examination showed that the previous excision had been incomplete. Inevitably, a local recurrence occurred a few months later. Herrera et al1 claim that hip and pelvic hydatid lesions were the most difficult locations to achieve healing outside the spine, as they achieved complete excision and healing in only two of the eight patients. When the extension within the affected bone is close to both extremities, total excision and reconstruction with megaprosthesis are the only alternatives to amputation. In case 2, a total femoral excision was decided upon, as the disease extended from the proximal to distal metaphysis. Wirbel et al26 27 also recommended to treat hydatid disease of the pelvis and femur with radical resection and hip replacement with a megaprosthesis. Postoperative wound infection is not rare after such long surgical procedures. The treatment of recurrence and infection may involve revision surgery and requires the patient's consent. Moreover, owing to the high occurrence of recurrences, in our opinion, a long-term treatment, even up to several years, by albendazole, with regular monitoring of blood levels should be considered. The treatment could be stopped as soon as the serodiagnosis of hydatidosis becomes negative. Prevention of osseous hydatidosis could rely on systematic prescription of albendazole preoperatively and postoperatively and, particularly, when several cysts are removed. Though there is some evidence that albendazole is active on the viability of the intracysts scolexes,28 29 this suggestion should be backed up by further studies.

Learning points.

Osseous hydatidosis is a very serious parasitic disease requiring radical surgical excision.

Owing to the high recurrence rate, long-term treatment by albendazole with regular monitoring of blood levels is recommended.

The prevention of osseous hydatidosis requires systematic prescription of albendazole preoperatively and postoperatively, and particularly when several cysts are removed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following people for their assistance, Hélène Yera (Department of Parasitology) for genotyping the parasite, Frédérique Larousserie and Alexandre Rouquette (Department of Pathology) for macroscopic and histological analysis. Also to Jean Dupouy-Camet (Department of Parasitology) and Philippe Anract (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery) of Cochin hospital for attending to the patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: FL, BM, JDC and FS contributed equally to the writing of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Herrera A, Martinez AA. Extraspinal bone hydatidosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003;2013:1790–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarwal S, Shah A, Kadhi SK, et al. Hydatid bone disease of the pelvis. A report of two cases and review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1992;2013:251–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Booz MK. The management of hydatid disease of bone and joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1972;2013:698–709 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szypryt EP, Morris DL, Mulholland RC. Combined chemotherapy and surgery for hydatid bone disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1987;2013:141–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charles RW, Govender S, Naidoo KS. Echinococcal infection of the spine with neural involvement. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1988;2013:47–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneppenheim M, Jerosch J. Echinococcosis granulosus/cysticus of the tibia. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2003;2013:107–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zlitni M, Ezzaouia K, Lebib H, et al. Hydatid cyst of bone: diagnosis and treatment. World J Surg 2001;2013:75–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaffe H. Metabolic, degenerative, and inflammatory diseases of the bone and joints. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Feibiger, 1972 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrandez HD, Gomez-Castresana F, Lopez-Duran L, et al. Osseous hydatidosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1978;2013:685–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sami A, Elazhari A, Ouboukhlik A, et al. Hydatid cyst of the spine and spinal cord. Study of 24 cases. Neurochirurgie 1996;2013:281–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez AA, Herrera A, Cuenca J, et al. Hydatidosis of the pelvis and hip. Int Orthop 2001;2013:302–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loudiye H, Aktaou S, Hassikou H, et al. Hydatid disease of bone. Review of 11 cases. Joint Bone Spine 2003;2013:352–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papanikolaou A, Antoniou N, Pavlakis D, et al. Hydatid disease of the tarsal bones. A case report. J Foot Ankle Surg 2005;2013:396–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sapkas GS, Stathakopoulos DP, Babis GC, et al. Hydatid disease of bones and joints. 8 cases followed for 4–16 years. Acta Orthop Scand 1998;2013:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takakuwa M, Katsuki M, Matsuno T, et al. Hydatid disease at the proximal end of the clavicle. J Orthop Sci 2002;2013:505–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arazi M, Erikoglu M, Odev K, et al. Primary echinococcus infestation of the bone and muscles. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005;2013:234–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pamir MN, Akalan N, Ozgen T, et al. Spinal hydatid cysts. Surg Neurol 1984;2013:53–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Booz MY. The value of plain film findings in hydatid disease of bone. Clin Radiol 1993;2013:265–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santivanez SJ, Sotomayor AE, Vasquez JC, et al. Absence of brain involvement and factors related to positive serology in a prospective series of 61 cases with pulmonary hydatid disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008;2013:84–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hernandez-Gonzalez A, Muro A, Barrera I, et al. Usefulness of four different Echinococcus granulosus recombinant antigens for serodiagnosis of unilocular hydatid disease (UHD) and postsurgical follow-up of patients treated for UHD. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2008;2013:147–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Csotye J, Sisak K, Bardocz L, et al. Pathological femoral neck fracture caused by an echinococcus cyst of the vastus lateralis—case report. BMC Infect Dis 2011;2013:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haralabidis S, Diakou A, Frydas S, et al. Long-term evaluation of patients with hydatidosis treated with albendazole and praziquantel. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2008;2013:429–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cobo F, Yarnoz C, Sesma B, et al. Albendazole plus praziquantel versus albendazole alone as a pre-operative treatment in intra-abdominal hydatisosis caused by Echinococcus granulosus. Trop Med Int Health 1998;2013:462–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lima RM, Ferreira MA, de Jesus Ponte Carvalho TM, et al. Albendazole-praziquantel interaction in healthy volunteers: kinetic disposition, metabolism and enantioselectivity. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2011;2013:528–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perez-Molina JA, Diaz-Menendez M, Gallego JI, et al. Evaluation of nitazoxanide for the treatment of disseminated cystic echinococcosis: report of five cases and literature review. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2011;2013:351–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wirbel RJ, Mues PE, Mutschler WE, et al. Hydatid disease of the pelvis and the femur. A case report. Acta Orthop Scand 1995;2013:440–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wirbel RJ, Schulte M, Maier B, et al. Megaprosthetic replacement of the pelvis: function in 17 cases. Acta Orthop Scand 1999;2013:348–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bildik N, Cevik A, Altintas M, et al. Efficacy of preoperative albendazole use according to months in hydatid cyst of the liver. J Clin Gastroenterol 2007;2013:312–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keshmiri M, Baharvahdat H, Fattahi SH, et al. Albendazole versus placebo in treatment of echinococcosis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2001;2013:190–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]