Abstract

Superior mesenteric arteriovenous fistulas are rare, especially when iatrogenic in origin. Management of these fistulas can be surgical or endovascular. Endovascular embolisation is the preferred modality with a low rate of complications. Among the reported complications, bowel ischaemia is considered an unlikely occurrence. We report a case of a complex iatrogenic arterioportal fistula that was managed by endovascular embolisation and controlled through both its inflow and outflow, and was later complicated by bowel ischaemia.

Background

Arterioportal fistulas are relatively uncommon. Such fistulas usually involve the hepatic or splenic arteries with a death rate, in untreated cases, that can reach approximately 25%.1 Arterioportal fistulas involving the superior mesenteric circulation are quite uncommon and are frequently observed in patients who have sustained major abdominal traumas or iatrogenic injuries during bowel resection.2 3

The diagnosis is usually made by CT scan or mesenteric angiography. While multidetector CT scans are useful for preoperative planning as they can determine the three-dimensional relationship of the fistula with the surrounding structures, angiography provides full anatomical details and provides better guidance for potential endovascular management.4 5

In this article, we present a case of an iatrogenic superior mesenteric artery (SMA) to vein fistula in a man that occurred after performing a right hemicolectomy 3 years earlier for benign diverticular bleed. The fistula was successfully closed via endovascular embolisation but complicated with bowel ischaemia.

Case presentation

A 61-year-old man, with a history of right hemicolectomy for diverticular bleed, presented to the emergency department 3 years later with diffuse abdominal pain and fresh blood per rectum (haematochezia). Further interrogation revealed that the patient complained of abdominal angina. The patient was mildly tachycardic (105 bpm) and tachypnoeic (23 breaths/min). Blood pressure was 130/85. On physical examination, he was conscious, cooperative and oriented. He had pale skin and mildly injected conjunctiva. Abdominal examination revealed diffuse tenderness without guarding.

Investigations

A CT scan showed dilated and torturous mesenteric vessels within the right lower quadrant corresponding to an arteriovenous fistula between the SMA and the superior mesenteric vein (SMV). It also showed the presence of surgical staples in the mesentery.

These findings were not noted on earlier CT scans performed before undergoing laparoscopic right hemicolectomy 3 years earlier.

Blood examinations showed elevated liver function tests. Therefore, the decision was made to correct the superior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula. Considering the patient's previous abdominal surgery, an endovascular approach was less invasive and more suitable for the patient.

Differential diagnosis

The most likely diagnoses of abdominal pain and/or lower gastrointestinal bleeding are upper gastrointestinal bleeding, diverticulosis, inflammatory bowel disease and bleeding tumour. Less common conditions presenting with this clinical picture include arteriovenous malformations, colonic/rectal varices and ischaemic colitis/mesenteric vascular insufficiency.

Treatment

A selective aortogram of the SMA was carried out, which showed the arteriovenous fistula; it was a complex fistula with multiple feeding arteries and a single draining vein (figure 1). A microcatheter was used to inject glue (Onyx 18, Micro Therapeutics, California, USA) into the arterial circulation and two niduses were occluded. However, owing to the complexity of the fistula it could not be controlled by the occlusion of the feeding arteries, so the decision was made to control the outflow. A transhepatic portal access was then obtained and a 10 cm balloon occluded run was performed to further delineate the anatomy of the fistula (figure 2). The stump of the arteriovenous malformation at the level of the distal SMV was delineated on contrast injection. A 4F glide C2 catheter was inserted distally in the portal circulation draining the fistula and multiple coils (10×12 and 10×15) were deployed to occlude the venous outflow (figure 3). Finally, contrast injection from the arterial side was injected, which showed complete obliteration of the fistula.

Figure 1.

Selective angiography of the superior mesenteric artery showing multiple niduses of the arteriovenous fistula with a large draining vein.

Figure 2.

Balloon-occluded run in the enlarged draining vein.

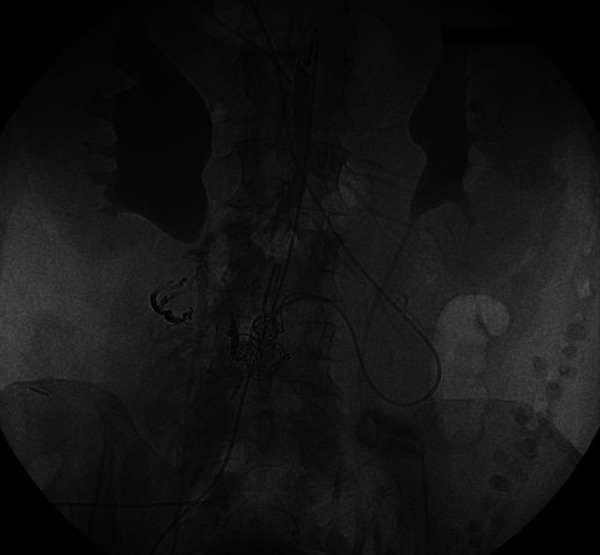

Figure 3.

Coiling of the draining vein. Note is made of glue going into the nidus from the arterial side.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient's abdominal pain and discomfort improved during the first 2 days postembolisation. On the third day, the patient started deteriorating and complaining of new onset diffuse abdominal pain. CT of the abdomen showed the wall thickening, involving several small bowel loops with free fluid within the abdomen suggesting changes of venous congestion without being able to rule out the possibility of bowel ischaemia. The fistula was completely occluded with no evidence of thrombus extension to the portal or the SMV. Lactic acid level in arterial blood was mildly elevated to 3.77 mmol/l (normal range 0.55–2.20) and procalcitonine level was 0.18 ng/ml, suggestive of a low risk of severe sepsis.

The surgery team elected to take the patient for a diagnostic laparoscopy. Intraoperative laparoscopy revealed gangrenous ileum and laparotomy for gangrenous ileal resection (40 cm) with primary anastomosis was performed. Histopathological examination of the resected bowel segment was consistent with ischaemia due to venous congestion.

The patient had a smooth postoperative course and was discharged from the hospital 1 week later. A follow-up CT scan performed 7 months later showed resolution of the venous congestion with normal calibre of the SMV, stable occluded fistula and embolic material in the branches of the mesenteric vein. By then, the patient also had normal liver function tests.

Discussion

Superior mesenteric arteriovenous fistulas are rare entities. Most of them are associated with blunt abdominal trauma and a few with iatrogenic causes. The first iatrogenic case was reported in 1960 after bowel resection for gangrenous bowels.6 Possible explanations for iatrogenic fistulas could include a suture that passes through the artery and vein during an earlier operation, which was presumably the case in our patient. Some articles have described noting such sutures at the fistula site.7

Superior mesenteric fistula patients return for medical attention with different complaints ranging from simple abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea to more severe symptoms of ascites, mesenteric ischaemia, bleeding or right-sided heart failure.8–11 Our patient presented with symptoms of abdominal angina indicating insufficient blood flow delivered to the mesenteric viscera. These fistulas can also manifest up to 10 years after the predisposing event and can remain asymptomatic.8 12 Once identified, intervention for treatment is highly recommended to prevent portal hypertension.

Superior mesenteric fistulas were classically treated with surgery10 12 but with time surgical approaches are being aborted and more endovascular approaches using stents and coils are being adopted.11–14 Endovascular embolisation of superior mesenteric fistulas is mainly a less invasive procedure and remains the treatment of choice for patients with a history of abdominal surgeries, as described in our case, knowing the challenges of performing surgery and manipulating bowels in the presence of adhesions.

Most reports have focused on the use of coils13 to embolise SMA fistulas. The first reported case was in 1982 by Uflacker et al.15 Recently, there have been few case reports and case series describing the use of stents and stent grafts.11 14

The main reported complications following endovascular embolisation of superior mesenteric fistulas are coil migration and extension of the thrombus into the portal system. Distal embolisation into the portal vein can lead to portal vein thrombosis13 or embolisation into the distal SMA or back into the aorta resulting in bowel infarction or lower extremity ischaemia.

Bowel ischaemia is a gastrointestinal emergency. It may occur as a result of mesenteric vascular occlusion and/or hypoperfusion. The clinical consequences can be catastrophic, with sepsis, bowel infarction and death, making rapid diagnosis and treatment imperative. Diagnosis is very challenging as bowel ischaemia may develop insidiously and in patients who are debilitated or have multiple medical problems. Acute intestinal ischaemia carries a death rate of approximately 70%. However, survival rate may be improved by early diagnosis and appropriate surgical intervention.16 Bowel ischaemia has been mentioned as a potential complication following iatrogenic endovascular embolisation, but it was considered an unlikely occurrence in previous publications and was never reported. This was attributed to the configuration of the fistula; superior mesenteric fistulas are of H or U type, and mainly of U type when iatrogenic in origin. The U type signifies that the artery connects directly to the vein with no bowel distal to it being supplied with blood; therefore, embolising the feeding artery will not affect the distal bowel. The H type is the type of all the traumatic cases and some of the iatrogenic fistulas; the artery and vein communicate from side to side through a false aneurysm and therefore are still supplying blood to the bowel distal to the fistula.17 The superior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula presented in our patient was neither of the two types. It was a complex fistula with multiple feeding arteries and a single draining vein. Embolisation of the fistula resulted in mesenteric venous outflow obstruction shown by the venous congestion that was noted on the CT scan performed 3 days after the procedure. This outflow obstruction subsequently resulted in bowel ischaemia due to venous insufficiency.

The endovascular outflow embolisation we performed might be the reason for this venous ischaemia; however, what is evident is that these type of fistulas could not be controlled by simple feeding artery occlusion and require additional outflow occlusion. This raises attention to a more careful approach towards complex arteriovenous fistulas and more reports are needed to justify whether the endovascular management of these entities is advised or not.

Our case describes a complex iatrogenic arterioportal fistula that was embolised through an endovascular approach and was complicated by bowel ischaemia. Although this will remain a rare complication, more extensive and evident information is needed to reveal the mechanism responsible for bowel wall ischaemia post fistulas embolisation and to possibly predict and prevent this occurrence, especially with complex fistulas.

Learning points.

Arterioportal fistulas involving the superior mesenteric circulation are uncommon and are secondary to major abdominal traumas or iatrogenic injuries during bowel resection.

Diagnosis may be challenging as patients can present with variable signs and symptoms, even years after the predisposing event.

Endovascular embolisation of superior mesenteric fistulas is mainly less invasive than surgery and remains the treatment of choice for patients with a history of abdominal surgeries.

The main reported complications following endovascular embolisation of superior mesenteric fistulas are coil migration and extension of the thrombus into the portal system, which may rarely result in bowel ischaemia.

Complex superior mesenteric fistulas need embolisation of the outflow in addition to the embolisation of the feeding arteries, and bowel ischaemia may also occur as a consequence of venous insufficiency.

Footnotes

Contributors: GI and MH drafted the manuscript and performed the literature review. SM contributed in carrying out the medical literature search. AH participated in the care of the patient, conceived and designed the article, and supervised and revised the final report.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Van Way CW, III, Crane JM, Riddell DH, et al. Arteriovenous fistula in the portal circulation. Surgery 1971;2013:876–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenthal D, Ellison RG, Jr, Luke JP, et al. Traumatic superior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula: report of a case and review of the literature. J Vasc Surg 1987;2013:486–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Francois F, Thevenet A. Superior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula after ileal resection. Ann Vasc Surg 1992;2013:370–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radonic V, Baric D, Petricević A, et al. Advances in diagnostics and successful repair of proximal posttraumatic superior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula. J Trauma 1995;2013:305–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radin DR, Allgood MR, Johnson MB, et al. CT diagnosis of superior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1989;2013:721–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Movitz D. Postoperative arteriovenous aneurysm in mesentery after small bowel resection. JAMA 1960;2013:42–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paloyan D, Collins PA, Washburn FP. Superior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula. Am Surg 1974;2013:481–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato S, Nakagawa T, Kobayashi H, et al. Superior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula: report of a case and review of the literature. Surg Today 1993;2013:73–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reed JK, McGiin RF, Gorman JF, et al. Traumatic mesenteric arteriovenous fistula presenting as the superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Arch Surg 1986;2013:1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YC, Tan GA, Lin BM, et al. Superior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula presenting 10 years after extensive small bowel resection. Aust N Z J Surg 2000;2013:822–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu CG, Li YD, Li MH. Post-traumatic superior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula: endovascular treatment with a covered stent. J Vasc Surg 2008;2013:654–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiriano J, Abou-Zamzam AM, Jr, Teruya TH, et al. Delayed development of a traumatic superior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula following multiple gunshot wounds to the abdomen. Ann Vasc Surg 2005;2013:470–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desai SB, Modhe JM, Aulakh BG, et al. Percutaneous transcatheter steel-coil embolization of a large proximal post-traumatic superior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula. J Trauma 1987;2013:1091–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeo KK, Dawson DL, Brooks JL, et al. Percutaneous treatment of a large superior mesenteric artery pseudoaneurysm and arteriovenous fistula: a case report. J Vasc Surg 2008;2013:730–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uflacker R, Saadi J. Transcatheter embolization of superior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1982;2013:1212–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tendler DA. Acute intestinal ischemia and infarction. Semin Gastrointest Dis 2003;2013:66–76 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donell ST, Hudson MJK. Iatrogenic superior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula report of a case and review of the literature. J Vasc Surg 1988;2013:335–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]